CHAPTER 39 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 39 – Open Elbow Contracture Release

Diego Fernandez, MD, PD

Elbow motion can be restricted by contracture of the skin, capsule, and muscles; heterotopic ossification, osteophytes, or implants; articular incongruity or damage; and malunion or nonunion.[21] Ulnar neuropathy is commonly associated with elbow contracture and can be precipitated or exacerbated by surgeries that increase mobility.[2] The best candidate for an arthroscopic elbow contracture release is a patient with capsular contracture with or without osteophytes. Most patients with pure capsular contractures after trauma can achieve functional motion with time and exercises (including static progressive or dynamic elbow splinting). [5] [8] Primary elbow arthritis is uncommon. Patients with less than 100 degrees of flexion or preexisting ulnar neuropathy merit ulnar nerve decompression.[2] Once the ulnar nerve is released, it is straightforward to perform a capsular excision from the medial side.[13] Arthroscopic elbow contracture release is more difficult and more dangerous than open contracture release, particularly because elbow arthroscopy is an uncommon procedure at which most of us are not well practiced. [3] [9] [14] [16] [24] For all of these reasons, operative treatment of elbow stiffness is best performed with an open procedure in most patients.

It is helpful to be aware of the details of prior trauma, burn, or central nervous system injury, prior surgeries in particular. In patients with prior central nervous system injury, one must determine the ability of the patient to participate in a postoperative rehabilitation protocol.[34] A painful contracture suggests arthritis or ulnar neuropathy. Numbness and dexterity problems suggest ulnar neuropathy.

The quality of the skin is important, particularly in post-burn contractures.[28] The status of the skin with respect to prior injury and operative treatment will influence the operative tactics. When planning operative treatment of a posttraumatic contracture, we prefer to wait until the skin and scar are mobile and soft and no longer edematous or adherent. A complete motor and sensory examination of the ulnar nerve is performed along with evaluation for Tinel sign and an elbow flexion test.

Standard anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the elbow are usually sufficient to identify and to characterize arthritis, heterotopic ossification, and nonunions, but computed tomography is occasionally of use. In more complex cases, the computed tomographic scan can help with preoperative planning.[34] Three-dimensional reconstructions are particularly easy to interpret. Computed tomographic scans may be particularly useful for characterizing malunion of the articular surface of the distal humerus.[20]

Neurophysiologic testing should be considered when there is any possibility of preoperative ulnar neuropathy.

Indications and Contraindications

Morrey et al[23] found that 15 daily activities could be accomplished with an arc of ulnohumeral motion between 30 and 130 degrees of flexion and an arc of forearm rotation from 50 degrees of pronation to 50 degrees of supination. However, these numbers should not be used to decide when to operate on elbow stiffness. Patients can adapt to and function well with much less motion,[6] perhaps more so when the stiffness is in the nondominant elbow. Therefore, the indication for operative contracture release is a combination of diminished elbow motion and disability directly related to stiffness.

Simple capsular contracture (no heterotopic bone, no malunion or nonunion, no implants blocking motion, no ulnar neuropathy) usually responds to reassurance and encouragement of exercises, time, and static progressive or dynamic elbow splinting.[5] Therefore, one should never rush into operative treatment of capsular contracture; patience and frequent visits for reassurance and encouragement are worthwhile.

Obvious hindrances to motion, including heterotopic bone, malunion, nonunion, prominent implants, and ulnar neuropathy, merit immediate operative treatment. Heterotopic ossification can be resected within 4 months of injury (when it is radiographically mature and the skin is mobile with little or no edema) regardless of activity on bone scans. [15] [28] [33] [34] Stiffness associated with advanced arthrosis or unsalvageable nonunion or malunion should be treated by interpositional or prosthetic elbow arthroplasty. [21] [22]

Elbow capsulectomy can be performed simultaneously with débridement of a deep infection. It also forms an integral part of the treatment of malunion,[20] nonunion,[11] and instability.[26] Unstable skin can be treated with either prior or concomitant procedures to improve soft tissue coverage.[28]

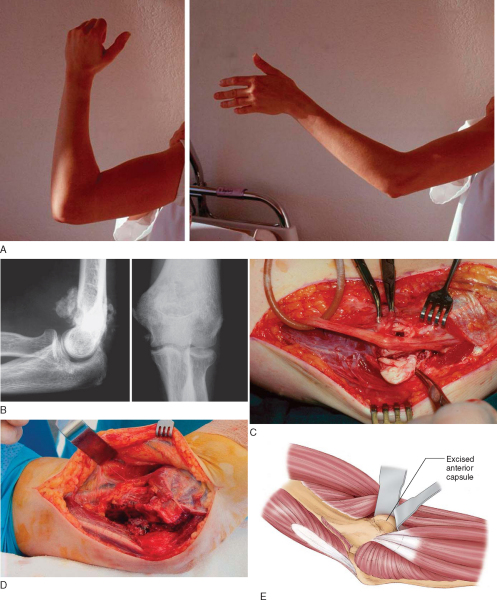

Patients with capsular contracture who desire extension can be treated with lateral capsulectomy (

Fig. 39-1

). [4] [19] Patients with concomitant ulnar neuropathy or limitation of elbow flexion are best treated with medial capsulectomy (

Fig. 39-2

). [13] [36] Patients with heterotopic bone, prominent implants, or complex contracture that cannot be adequately released from medial or lateral alone may benefit from a combined release. [13] [28] Preoperative (within 24 hours) radiation therapy (a single 7-Gy dose) is administered to patients with heterotopic bone to be excised.

|

|

|

|

Figure 39-1 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 39-2 |

Direct anterior release[32] is rarely necessary because the anterior capsule can be more safely excised from medial or lateral. A posterior release with splitting of the triceps and fenestration of the olecranon fossa for access to the anterior elbow is used primarily for débridement of primary elbow arthrosis.[2]

This chapter describes elbow capsulectomy through lateral (

Fig. 39-1

) and medial (

Fig. 39-2

) intervals.

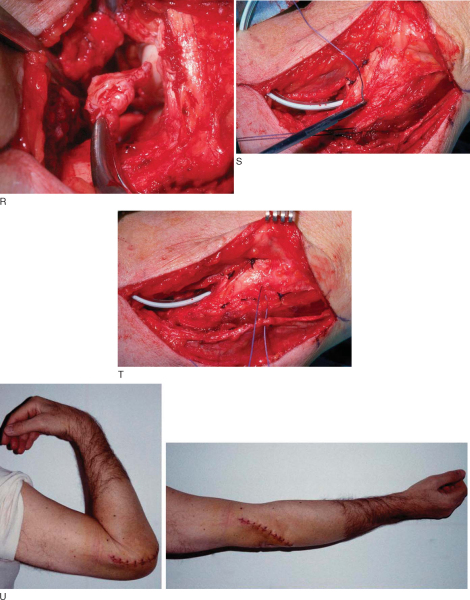

Open elbow contracture release can be performed under general anesthesia or brachial plexus block. The patient is supine, and the arm is supported on a hand table. A sterile tourniquet is applied to the upper arm.

The skin incision can be straight and directly over the muscle interval to be used or posterior with a skin flap elevated to expose the muscle interval (

Fig. 39-1C

). If both medial and lateral intervals are to be used, a single posterior incision or both medial and lateral incisions can be made. In the unusual case of a direct anterior release, a direct anterior skin incision that crosses the flexion creases obliquely is made.

Lateral Elbow Capsulectomy (

Box 39-1

)

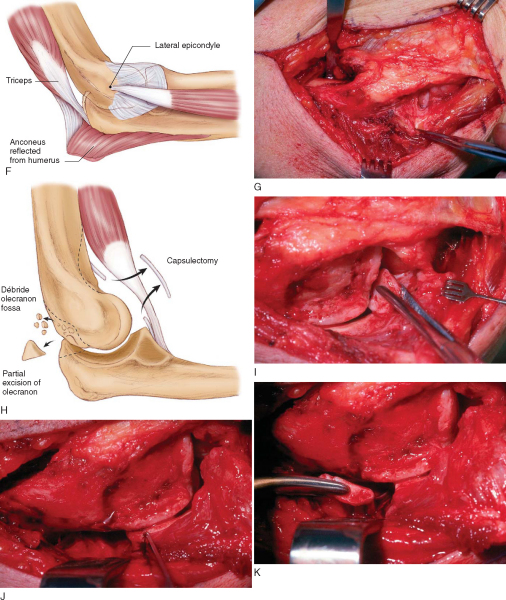

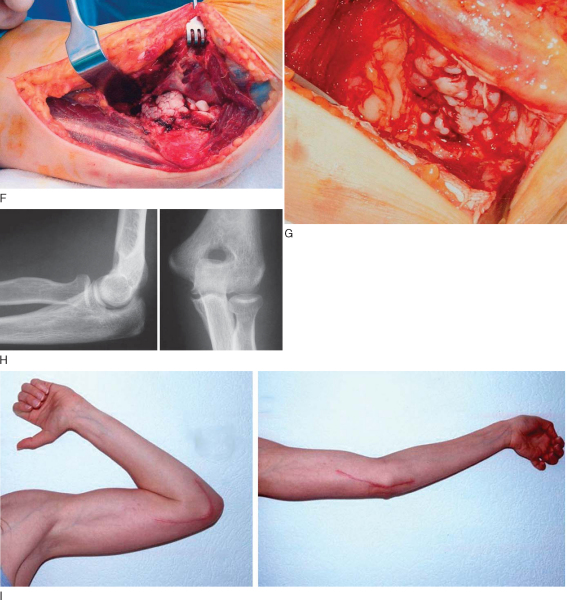

1. Lateral Approach and Posterior Dissection

Release of elbow stiffness from the lateral side preserves the common wrist and digit extensors overlying the lateral collateral ligament. The skin is mobilized off the fascia to help identify the appropriate deep muscle interval (

Fig. 39-1D

). Deep dissection begins by identification of the supracondylar ridge, dividing the overlying fascia and exposing the ridge (

Fig. 39-1E

). The triceps is elevated off the posterior humerus and elbow capsule (

Fig. 39-1F

). The posterior dissection continues distally in the interval between the anconeus and extensor carpi ulnaris. The anconeus is elevated off the capsule, the humerus, and the ulna (

Fig. 39-1G

). Care is taken to preserve the lateral collateral ligament complex while the posterior elbow capsule is excised. The olecranon fossa is cleared out and even burred to deepen it if necessary (

Fig. 39-1H

). Loose bodies are identified and removed (

Fig. 39-1I

). The tip of the olecranon can also be excised (

Fig. 39-1J and K

).

| Surgical Steps for Lateral Capsulectomy | |||||||||

|

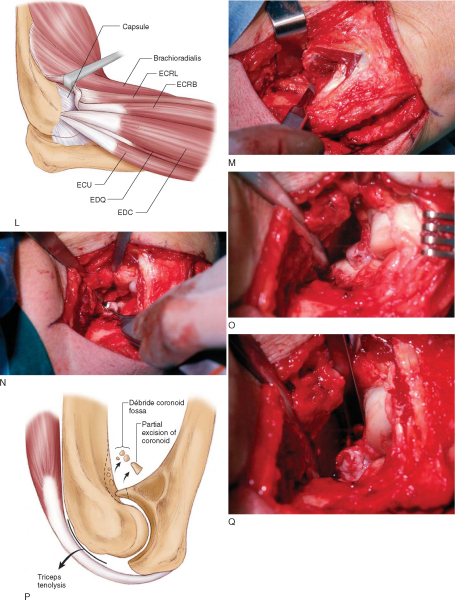

The origin of the extensor carpi radialis and part of the origin of the brachioradialis are released and elevated along with the brachialis off the anterior humerus and elbow capsule (

Fig. 39-1L and M

). Distally, an interval is developed just anterior to the midportion of the capitellum, roughly corresponding to the split between the extensor carpi radialis brevis and the extensor digitorum communis, although in practice the interval is not precise (

Fig. 39-1L, N, and O

). Keeping the dissection over the anterior half of the radiocapitellar joint will protect the lateral collateral ligament complex. The anterior elbow capsule is excised (

Fig. 39-1N

).

At the medial side of the elbow, the capsulectomy may transition to a capsulotomy for safety, depending on visualization (

Fig. 39-1O

). The radial and coronoid fossae can be cleared out and deepened as needed (

Fig. 39-1P

). The tip of the coronoid can be excised (

Fig. 39-1Q and R

). Resection of a deformed radial head may also be helpful in some patients.

Both the anterior and the posterior muscle intervals are sutured (

Fig. 39-1S and T

). Drains are used at the discretion of the surgeon. The skin is closed according to the surgeon’s preference.

After skin incision, the ulnar nerve is identified on the medial border of the triceps. A complete release of the nerve through the arcade of Struthers, Osborne ligament, and flexor-pronator aponeurosis is then performed, along with neurolysis of the ulnar nerve if there is extensive scarring (

Fig. 39-2C

). Skin flaps can be safely elevated once the ulnar nerve is identified and protected.

The flexor-pronator mass is identified and split in half between the interval where the ulnar nerve runs and the anterior margin of the muscle mass. The anterior half of the flexor-pronator mass and the brachialis muscle are elevated off the anterior humerus and elbow capsule (

Fig. 39-2D to F

). The triceps is elevated off the distal humerus and the posterior elbow capsule (

Fig. 39-2G

). Capsular excision, fossae deepening, and coronoid and olecranon tip excision are as described for lateral capsulectomy.

Heterotopic Bone Excision and Other Factors

Heterotopic bone is excised piecemeal, with care taken to identify and to protect native bone and articulation. Bleeding bone surfaces are covered with bone wax. Implants are removed after capsulectomy and elbow manipulation to limit the risk of fracture. Malunion and nonunion are addressed as necessary.

Gravity-assisted and active-assisted range of motion exercises are initiated the morning after surgery. Static progressive or dynamic splints are used in patients who have trouble maintaining motion obtained in surgery. These splints are initiated as soon as the wound is stable.

Complications include recurrent stiffness and ulnar neuropathy (due to restoration of flexion or to handling of the nerve).

The majority of published case series reporting the results of open elbow contracture release describe a single technique used to treat patients with a variety of diagnoses (

Table 39-1

). The results of various techniques seem comparable, although few data are available about the use of a medial exposure for posttraumatic contractures. [25] [36] In general, about 75% regain at least an 80-degree arc of flexion.[25] Patients with limited flexion—particularly due to primary osteoarthritis—may be susceptible to ulnar neuropathy after release.[2] The results of excision of subtotal heterotopic ossification may be superior to the results of capsular contracture release alone,[18] but the results of excision of complete bone ankylosis, although generally rewarding, are less predictable.[28]

| Author | No. of Patients | Diagnosis | Operative Technique | Preoperative Arc (degrees) | Postoperative Arc (degrees) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tosun et al[31] (2006) | 22 | Posttraumatic | Combined lateral and medial | 35 | 86 |

| Ring et al[25] (2006) | 46 | Posttraumatic | Patient-specific, variable | 45 | 103 |

| Tan et al[30] (2006) | 52 | Posttraumatic | Patient-specific, variable | 57 | 116 |

| Ring et al[27] (2005) | 42 | Posttraumatic | Patient-specific, variable; 23 had hinged external fixation | 21 | 105 |

| Aldridge et al[1] (2004) | 77 | Posttraumatic | Anterior; most with continuous passive motion postoperatively | 59 | 97 |

| Gosling et al[7] (2004; Epub May 30, 2003) | 59 | Posttraumatic | Patient-specific, variable | 68 | 101 |

| Wu[37] (2003) | 20 | Posttraumatic | Patient-specific, variable | 47 | 118 |

| Heirweg and De Smet[10] (2003) | 16 | Posttraumatic | Patient-specific, variable | 47 | 87 |

| Stans et al[29] (2002) | 37 | Mixed; age younger than 21 years | Patient-specific, variable | 66 | 94 |

| Wada et al[35] (2000) | 13 | Posttraumatic | Medial | 46 | 110 |

| Kraushaar et al[17] (1999) | 12 | Posttraumatic | Lateral | 70 | 117 |

| Mansat and Morrey[19] (1998) | 37 | Mixed | Lateral | 49 | 94 |

| Cohen and Hastings[4] (1998) | 22 | Posttraumatic | Lateral | 74 | 129 |

| Hertel et al[12] (1997) | 26 | Mixed | Patient-specific, variable | 66 | 100 |

1.

Aldridge 3rd JM, Atkins TA, Gunneson EE, Urbaniak JR: Anterior release of the elbow for extension loss.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004; 86:1955-1960.

2.

Antuna SA, Morrey BF, Adams RA, O’Driscoll SW: Ulnohumeral arthroplasty for primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow: long-term outcome and complications.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002; 84:2168-2173.

3.

Ball CM, Meunier M, Galatz LM, et al: Arthroscopic treatment of posttraumatic elbow contracture.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002; 11:624-629.

4.

Cohen MS, Hastings H: Posttraumatic contracture of the elbow: operative release using a lateral collateral ligament sparing approach.

J Bone Joint Surg Br 1998; 80:805-812.

5.

Doornberg JN, Ring D, Jupiter JB: Static progressive splinting for posttraumatic elbow stiffness.

J Orthop Trauma 2006; 20:400-404.

6.

Doornberg JN, Ring D, Fabian LM, et al: Pain dominates measurements of elbow function and health status.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87:1725-1731.

7.

Gosling T, Blauth M, Lange T, et al: Outcome assessment after arthrolysis of the elbow.

Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2004; 124:232-236.Epub May 30, 2003.

8.

Green DP, McCoy H: Turnbuckle orthotic correction of elbow-flexion contractures after acute injuries.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1979; 61:1092-1095.

9.

Haapaniemi T, Berggren M, Adolfsson L: Complete transection of the median and radial nerves during arthroscopic release of posttraumatic elbow contracture.

Arthroscopy 1999; 15:784-787.

10.

Heirweg S, De Smet L: Operative treatment of elbow stiffness: evaluation and outcome.

Acta Orthop Belg 2003; 69:18-22.

11.

Helfet DL, Kloen P, Anand N, Rosen HS: Open reduction and internal fixation of delayed unions and nonunions of fractures of the distal part of the humerus.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85:33-40.

12.

Hertel R, Pisan M, Lambert S, Ballmer F: Operative management of the stiff elbow: sequential arthrolysis based on a transhumeral approach.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1997; 6:82-88.

13.

Hotchkiss RN: Elbow contracture.

In: Green DP, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, ed. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery,

Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:667-682.

14.

Jones GS, Savoie 3rd FH: Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow.

Arthroscopy 1993; 9:277-283.

15.

Jupiter JB, Ring D: Operative treatment of posttraumatic proximal radioulnar synostosis.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998; 80:248-257.

16.

Kim SJ, Kim HK, Lee JW: Arthroscopy for limitation of motion of the elbow.

Arthroscopy 1995; 11:680-683.

17.

Kraushaar BS, Nirschl RP, Cox W: A modified lateral approach for release of posttraumatic elbow flexion contracture.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1999; 8:476-480.

18.

Lindenhovius AL, Linzel DS, Doornberg JN, et al. Comparison of elbow contracture release in elbows with and without heterotopic ossification restricting motion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg (in press).

19.

Mansat P, Morrey BF: The column procedure: a limited lateral approach for extrinsic contracture of the elbow.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998; 80:1603-1615.

20.

McKee MD, Jupiter JB, Toh CL, et al: Reconstruction after malunion and nonunion of intraarticular fractures of the distal humerus.

J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994; 76:614-621.

21.

Morrey BF: Posttraumatic contracture of the elbow. Operative treatment, including distraction arthroplasty.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990; 72:601-618.

22.

Morrey BF, Adams RA, Bryan RS: Total elbow replacement for posttraumatic arthritis of the elbow.

J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991; 73:607-612.

23.

Morrey BF, Askew LJ, Chao EY: A biomechanical study of normal functional elbow motion.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981; 63:872-880.

24.

Phillips BB, Strasburger S: Arthroscopic treatment of arthrofibrosis of the elbow joint.

Arthroscopy 1998; 14:38-44.

25.

Ring D, Adey L, Zurakowski D, Jupiter JB: Elbow capsulectomy for posttraumatic elbow stiffness.

J Hand Surg Am 2006; 31:1264-1271.

26.

Ring D, Hannouche D, Jupiter JB: Surgical treatment of persistent dislocation or subluxation of the ulnohumeral joint after fracture-dislocation of the elbow.

J Hand Surg Am 2004; 29:470-480.

27.

Ring D, Hotchkiss RN, Guss D, Jupiter JB: Hinged elbow external fixation for severe elbow contracture.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87:1293-1296.

28.

Ring D, Jupiter J: The operative release of complete ankylosis of the elbow due to heterotopic bone in patients without severe injury of the central nervous system.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85:849-857.

29.

Stans AA, Maritz NG, O’Driscoll SW, Morrey BF: Operative treatment of elbow contracture in patients twenty-one years of age or younger.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002; 84:382-387.

30.

Tan V, Daluiski A, Simic P, Hotchkiss RN: Outcome of open release for posttraumatic elbow stiffness.

J Trauma 2006; 61:673-678.

31.

Tosun B, Gundes H, Buluc L, Sarlak AY: The use of combined lateral and medial releases in the treatment of posttraumatic contracture of the elbow.

Int Orthop 2006;Oct 12 [Epub ahead of print].

32.

Urbaniak JR, Hansen PE, Beissinger SF, Aitken MS: Correction of posttraumatic flexion contracture of the elbow by anterior capsulotomy.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1985; 67:1160-1164.

33.

Viola RW, Hanel DP: Early “simple” release of posttraumatic elbow contracture associated with heterotopic ossification.

J Hand Surg Am 1999; 24:370-380.

34.

Viola RW, Hastings H: Treatment of ectopic ossification about the elbow.

Clin Orthop 2000; 370:65-86.

35.

Wada T, Ishii S, Usui M, Miyano S: The medial approach for operative release of posttraumatic contracture of the elbow.

J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000; 82:68-73.

36.

Wada T, Isogai S, Ishii S, Yamashita T: Débridement arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. Surgical technique.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87(suppl 1, pt 1):95-105.

37.

Wu CC: Posttraumatic contracture of elbow treated with intraarticular technique.

Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2003; 123:494-500.