CHAPTER 26 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 26 – Arthroscopic and Open Management of Scapulothoracic Disorders

John E. Kuhn, MD

Knowledge about the interplay of structures and biomechanics surrounding the scapula and its role in shoulder motion is evolving steadily. The result is that our understanding of shoulder disease is also increasing. It is becoming clear that processes affecting the scapula in turn greatly influence the function of the shoulder.[8] Conditions of the scapulothoracic articulation can be broadly divided into four main disease processes: bursitis, crepitus, dyskinesis, and winging. Each of these is a unique entity, but they are often seen in combination.

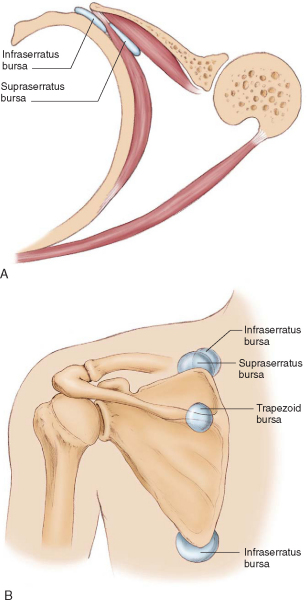

Scapulothoracic bursitis presents as posterior shoulder pain with range of motion. The patient can often localize the pain under the scapula. There are two major bursae that are consistently identified, the infraserratus bursa between the serratus and the chest wall and the supraserratus bursa between the subscapularis and the serratus (

Fig. 26-1

). In addition, four minor adventitial bursae have been described.[9] Clinically significant bursitis tends to affect two areas most commonly—the superior medial angle and the inferior angle. The bursae at these locations are minor adventitious bursae that may become apparent only when they are inflamed. Through a process that is similar to subacromial bursitis, repetitive motion of the scapula over the rib cage causes inflammation and edema in the bursae. As with other types of bursitis, this process can be initially treated with rehabilitation and judicious corticosteroid injections. This is often sufficient to quiet the process and relieve the patient’s symptoms. On occasion, the bursitis is refractory to medical management, and surgical intervention in the form of a bursectomy is required.

Scapular crepitus is a process whereby palpable and often audible noises are generated under the scapula. Of significance in this process is that not all crepitus is painful or pathologic, and the volume of the noise does not correlate with the severity of the pain. Crepitus ranges from mild, painless subscapular crunching to painless but loud snapping and from minimal discomfort to disabling pain. In most patients, symptomatic scapulothoracic crepitus is associated with bursitis.

Winging of the scapula is a finding that may result from many causes. In athletes, winging is typically seen as an isolated palsy of the serratus due to a long thoracic nerve neurapraxic injury. Winging may also be seen with profound scapular bursitis or may manifest as part of scapular dyskinesis. Scapular dyskinesis is defined as abnormal motion of the scapula characterized by medial border or inferior angle prominence, early excessive scapular elevation and shrugging, or rapid downward rotation during lowering of the arm.[8] A static abnormality of scapular position, called the SICK scapula, probably represents a more severe state of this condition.[2] Whereas dyskinesis is likely to be the most common finding in the athlete with shoulder pain, it is best treated with appropriate rehabilitation and will not be explored in detail in this chapter. Winging due to bursitis typically resolves with treatment of bursitis. Winging due to long thoracic nerve injury resolves spontaneously in most athletes; when it persists, surgical intervention can be considered.

|

|

|

|

Figure 26-1 (Redrawn from Kuhn JE, Hawkins RJ. Evaluation and treatment of scapular disorders. In Warner JJP, Iannotti JP, Gerber C, eds. Complex and Revision Problems in Shoulder Surgery. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1997:357-375.) |

Many scapulothoracic conditions in athletes are related to other pathologic processes in the shoulder, and as such, the history should include a thorough orthopedic review of systems. A typical history of the patient with a scapulothoracic disorder includes the following:

The physical examination for scapulothoracic disorders requires the physician to stand behind the patient, who is disrobed or wearing a sports bra. The scapular position at rest should be noted. A scapula that is depressed, anteriorly tilted, and internally rotated suggests a SICK scapula and typically has tenderness at the pectoralis minor insertion on the coracoid.[2] Patients are asked to elevate and then lower the arms while the physician looks for dyskinesis. Crepitus can be heard, and the location of crepitus (superomedial angle or inferior angle) frequently can be determined by careful palpation. Provocative testing to elicit winging can be performed by having the patient push off from the wall or elevate the arms against resistance (

Fig. 26-2

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 26-2 |

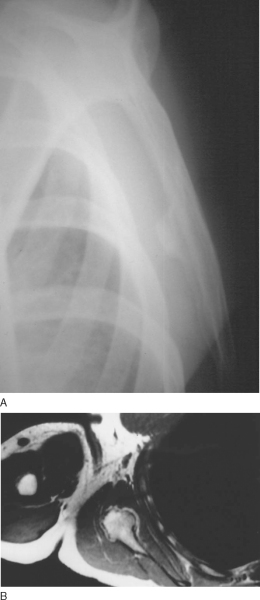

Radiographs are helpful to find subscapular bone prominences (

Fig. 26-3

) and include the following views:

| • | True anteroposterior view | |

| • | Axillary view | |

| • | Scapular Y view ( Fig. 26-3A ). |

|

|

|

|

Figure 26-3 |

Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomographic scans are usually not necessary but can be helpful in identifying soft tissue and bone lesions (

Fig. 26-3B

).

If winging of the scapula is thought to be of neurologic origin, electromyography will assist in the diagnosis. Serial studies every 3 to 4 months can document recovery of an injured long thoracic nerve.

Indications and Contraindications

Most scapulothoracic problems in athletes are not treated surgically. Rehabilitation focused on pectoralis minor stretching, serratus and lower trapezius strengthening, posterior capsule stretching, and core strengthening will treat the SICK scapula and scapular dyskinesis.[2] Patients with scapular bursitis and milder forms of crepitus will often respond to similar rehabilitation and the judicious use of corticosteroid injections. By mixing steroid and local anesthetic, injections can be therapeutic and diagnostic, perhaps giving an indication of potential postsurgical results. Athletes with long thoracic nerve injury can be monitored for many months with serial electromyography as the nerve typically recovers spontaneously, occasionally taking up to 2 years. Bracing may help with symptom relief while the nerve recovers. In patients for whom nonoperative approaches fail, surgery may be considered for these conditions.

There are no absolute contraindications to surgery of the scapula; however, physicians must be cautious of the patient with less than obvious pathologic changes, the patient with questionable responses to therapy and injection, and the patient who may have a voluntary component to the complaint. Scapulothoracic crepitus often exists without symptoms. In addition, some patients who have secondary gain develop voluntary scapular winging. Patients with secondary gain, unrecognized scapular dyskinesis, and voluntary winging will have predictably poor postsurgical outcomes.

Surgical Technique: Bursectomy and Partial Scapulectomy

Positioning of the patient is similar for both bursectomy and partial scapulectomy. The prone position is used, often with a bolster under the lateral chest to cause the rib cage to rise and the shoulder to fall forward, thereby making the scapula more prominent. The surgical preparation should extend from C5 to L1 and include the entire back and the arm of the involved side.

Bursectomy (

Box 26-1

)

Scapulothoracic bursectomy can be performed in an open or an endoscopic fashion. The open procedure has a distinct advantage in that it allows direct visualization of adventitial bursae whose position and plane of dissection might be anatomically variable.

In the open procedure for a superior medial bursectomy, the incision is placed medial to the superior vertebral border of the scapula. The trapezius is split in line with its fibers, and the levator scapulae and rhomboids are exposed. The levator and rhomboids are then incised off of the medial border of the scapula in a subperiosteal fashion. A plane is then developed between the serratus anterior under the scapula and the chest wall. The thickened bursa can be dissected from this space. The levator, rhomboids, and trapezius are then reapproximated to the scapula, and the skin is closed. Postoperatively, the patient uses a sling for comfort and begins passive physical therapy immediately. Once the periscapular muscles have healed adequately at approximately 3 to 4 weeks, active motion is initiated. Strengthening can begin at 12 weeks. For symptomatic inferior angle bursae, the incision can be made along the inferior medial border just distal to the angle. The trapezius and then the latissimus dorsi are split in line with their fibers, allowing direct access to the inferior angle and the bursa. After the bursa is excised, the muscles are reapproximated and skin is closed. Postoperative care and rehabilitation are the same.

The endoscopic approach to scapulothoracic bursitis involves the use of two or three portals to access the subscapular space.[11] The patient may be positioned in either the prone or lateral position. All portals must be kept at least 2 cm medial to the medial border of the scapula to prevent injury to the dorsal scapular nerve (

Fig. 26-4

). The first portal is inserted medial to the scapula and midway between the scapular spine and the inferior angle. Insufflation of the infraspinatus bursa with injection will help identify the plane of surgery. The blunt obturator and endoscope can then be inserted into the bursa. The second portal can be either superior or inferior, depending on the location of the pathologic process. The superior portal is made, once again at least 2 cm medial to the medial border of the scapula at the level of the scapular spine. This will allow access to the superior medial angle. If required, a third portal can be made at the inferior angle of the scapula in a similar fashion to access the inferior portion.[15] In all these portals, landmarks are few, and hemostasis is critical to allow adequate visualization. Once the bursectomy is performed, the portals are closed and the patient is placed into a sling. Activity is performed as tolerated.

|

|

|

|

Figure 26-4 (From Pavlik A, Ang K, Coghlan J, Bell S. Arthroscopic treatment of painful snapping of the scapula by using a new superior portal. Arthroscopy 2003;19:608-612.) |

Partial Scapulectomy (

Box 26-2

)

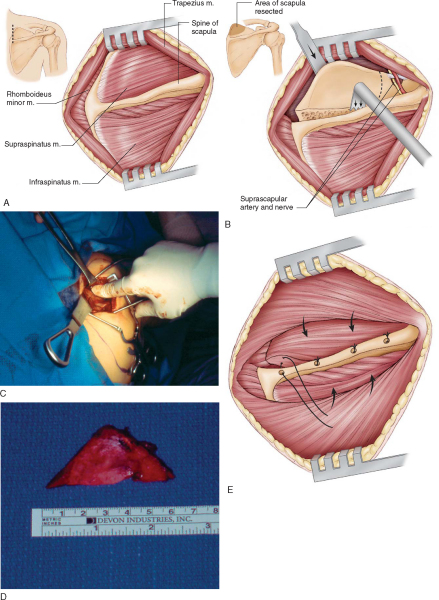

Painful scapulothoracic crepitus and its most dramatic presentation, the snapping scapula, are both treated with a partial scapulectomy when conservative measures fail. The pathologic lesion is generally at the superior medial angle, and so excision of this corner of the scapula is often successful at relieving symptoms. As in the bursitis procedures, the patient is placed prone.

| Surgical Steps: Scapulectomy | |||||||||||||||

Partial scapulectomy

|

The incision is placed along the medial border of the scapula from the level of the scapular spine inferiorly to the superomedial angle (

Fig. 26-5

). The skin is elevated in a subcutaneous plane, exposing the spine of the scapula laterally. The trapezius is split in line with its fibers and elevated from the spine of the scapula, and the plane between the undersurface of the trapezius and the supraspinatus is developed. Starting along the spine, the supraspinatus is then dissected free from medial to lateral in a subperiosteal fashion until the edge of the scapular notch can be palpated. It is important to not extend farther lateral as damage to the suprascapular nerve and artery can occur. Starting once again along the medial border, the levator and rhomboids are elevated off subperiosteally. With the superior medial border exposed, the dissection is carried subperiosteally around the border and under the scapula to peel the serratus and subscapularis off the bone. This is most easily done with a Cobb elevator. Once both sides of the scapula have been exposed, the superior corner can be resected. This cut is made with an oscillating saw and runs from the base of the scapular spine to approximately 4 or 5 cm lateral along the superior edge of the scapula. Once again, care must be taken to not disturb the contents of the scapular notch. With the superior medial angle resected, the plane between the supraspinatus and the combined muscle flap are sutured together with No. 2 permanent suture. The trapezius is secured to the spine of the scapula. Skin is closed, and the patient is placed into a sling.

|

|

|

|

Figure 26-5 (A, B, and E redrawn from Kuhn JE, Hawkins RJ. Evaluation and treatment of scapular disorders. In Warner JJP, Iannotti JP, Gerber C, eds. Complex and Revision Problems in Shoulder Surgery. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven 1997:357-375.) |

Passive range of motion can begin immediately. Active exercises start at 6 weeks, and strengthening begins at 12 weeks.

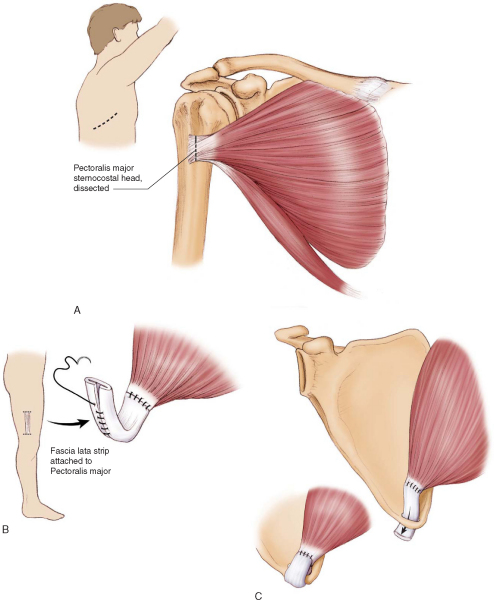

Operative treatment of scapular winging for patients whose therapy fails and who remain symptomatic is an attempt to restore stability in the face of a known deficiency. Because restoration of normal anatomy is not possible, these surgeries will have varying degrees of success and probably will not be able to return athletes to high levels of function.

Transfer of the sternal head of the pectoralis major muscle is the most popular therapy for permanent serratus anterior palsy (

Fig. 26-6

). For this procedure, the patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position. Either one or two incisions can be used. For a single incision, it is made across the axilla from the border of the pectoralis major anteriorly to the inferior angle of the scapula. The sternocostal head lies under the clavicular head at the insertion into the humerus. The sternocostal head is released and redirected back toward the inferior tip of the scapula. Because this muscle alone is generally not long enough to reach without excessive tensioning, an autologous fascia lata or hamstring tendon graft from the ipsilateral leg is harvested. The fascia lata graft is tubularized and sewn into the end of the pectoralis major tendon. The distal tip of the scapula is then cleared of soft tissues, and a small hole is made in the tip. The fascia lata graft is then passed through the hole and sutured back onto itself. Enough tension is applied so that the end of the pectoralis tendon is in contact with the scapula.

|

|

|

|

Figure 26-6 (Redrawn from Kuhn JE, Plancher KD, Hawkins RJ. Scapular winging. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1995;3:319-325.) |

The patient is placed into a sling, and postoperative passive range of motion is begun immediately. Active motion is begun at 6 weeks, and strengthening begins at 12 weeks.

The patient is kept in immobilization for up to 6 weeks after muscle transfer or fascial sling reconstructions. Passive therapy is begun immediately to avoid stiffness, and active motion is allowed at week 6. After these procedures, strengthening rehabilitation is begun around 12 weeks.

Any surgery that involves dissection under the scapula has the potential for chest wall complications, most notably pneumothorax. Postoperative radiographs will help identify any involvement of the lungs. Incisions and portals made midline to the medial border of the scapula can lead to dorsal scapular nerve injury. Splitting of the trapezius does not interfere with its innervation. If the superomedial angle of the scapula is resected too far laterally, the suprascapular nerve and artery are at risk.

| PEARLS AND PITFALLS | |||||||||||||||||||||

Pectoralis transfer for scapular winging

|

The results of these different procedures vary (Tables 26-1 to 26-3 [1] [2] [3]). Bursectomy and partial scapulectomy are surgeries with high success rates and satisfaction of patients. Muscle transfers and sling procedures have lower and less predictable results but may still be beneficial to the patient in terms of pain relief and improved function.

| Author | N and Technique | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Ciullo and Jones[3] (1993) | 13 arthroscopic bursectomy | 100% return to preinjury activity |

| McCluskey and Bigliani[12] (1991) | 9 open bursectomy | 89% good–excellent |

| Nicholson and Duckworth[13] (2002) | 17 open bursectomy | 100% relief of pain |

| Sisto and Jobe[17] (1986) | 4 open bursectomy | 4/4 return to professional pitching |

| Author | N and Technique | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Arntz and Matsen[1] (1990) | 12 patients, 14 shoulders | 86% complete relief |

| Harper et al[6] (1999) | 7 arthroscopic resections | 6 successful, 1 failure |

| Lehtinen et al[11] (2004) | 6 open, 6 combined open and scope, 2 scope, 2 bursectomy | 13/16 (81%) satisfied |

| Pavlik et al[15] (2003) | 10 arthroscopic resections | 4 excellent, 5 good, 1 fair |

| Richards and McKee[16] (1989) | 3 open resections | 100% success in pain relief |

| Author | N | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Connor et al[4] (1997) | 11 pectoralis transfers | 10/11 satisfactory |

| Gozna and Harris[5] (1979) | 3 pectoralis transfers | 3/3 successful |

| Iceton and Harris[7] (1987) | 15 pectoralis transfers | 9 satisfactory, 2 fair, 4 failures |

| Noerdlinger et al[14] (2002) | 15 pectoralis transfers | 2 excellent, 5 good, 4 fair, 4 poor |

| Steinmann and Wood[17] (2003) | 9 pectoralis transfers | 4 excellent, 2 good, 3 poor |

1.

Arntz CT, Matsen III FA: Partial scapulectomy for disabling scapulothoracic snapping.

Orthop Trans 1990; 14:252-253.

2.

Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB: The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology. Part III: the SICK scapula, scapular dyskinesis, the kinetic chain, and rehabilitation.

Arthroscopy 2003; 19:641-661.

3.

Ciullo JV, Jones E: Subscapular bursitis: conservative and endoscopic treatment of “snapping scapula” or “washboard syndrome.”.

Orthop Trans 1992–1993; 16:740.

4.

Connor PM, Yamaguchi K, Manifold SG, et al: Split pectoralis major transfer for serratus anterior palsy.

Clin Orthop 1997; 341:134-142.

5.

Gozna ER, Harris WR: Traumatic winging of the scapula.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1979; 61:1230-1233.

6.

Harper GD, McIlroy S, Bayley JI, Calvert PT: Arthroscopic partial resection of the scapula for snapping scapula: a new technique.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1999; 8:53-57.

7.

Iceton J, Harris WR: Treatment of winged scapula by pectoralis major transfer.

J Bone Joint Surg Br 1987; 69:108-110.

8.

Kibler WB, McMullen : Scapular dyskinesis and its relation to shoulder pain.

J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2003; 11:142-151.

9.

Kuhn JE, Plancher KD, Hawkins RJ: Symptomatic scapulothoracic crepitus and bursitis.

J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1998; 6:267-273.

10.

Kuhn JE, Plancher KD, Hawkins RJ: Scapular winging.

J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1995; 3:319-325.

11.

Lehtinen JT, Macy JC, Cassinelli E, Warner JJP: The painful scapulothoracic articulation.

Clin Orthop 2004; 423:99-105.

12.

McCluskey III GM, Bigliani LU: Surgical management of refractory scapulothoracic bursitis.

Orthop Trans 1991; 15:801.

13.

Nicholson GP, Duckworth MA: Scapulothoracic bursectomy for snapping scapula syndrome.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002; 11:80-85.

14.

Noerdlinger MA, Cole BJ, Stewart M, Post M: Results of pectoralis major transfer with fascia lata autograft augmentation for scapula winging.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002; 11:345-350.

15.

Pavlik A, Ang K, Coghlan J, Bell S: Arthroscopic treatment of painful snapping of the scapula by using a new superior portal.

Arthroscopy 2003; 19:608-612.

16.

Richards RR, McKee MD: Treatment of painful scapulothoracic crepitus by resection of the superomedial angle of the scapula: a report of three cases.

Clin Orthop 1989; 247:111-116.

17.

Sisto DJ, Jobe FW: The operative treatment of scapulothoracic bursitis in professional pitchers.

Am J Sports Med 1986; 14:192-194.

18.

Steinmann SP, Wood MB: Pectoralis major transfer for serratus anterior paralysis.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003; 12:555-560.