CHAPTER 13 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 13 – Open Repair of Multidirectional Instability

Gordon Nuber, MD

Neer and Foster[13] in 1980 described multidirectional instability as the ability to dislocate or to sublux the glenohumeral joint anteriorly, posteriorly, and inferiorly. They also reported that patients were most symptomatic during midrange of motion while performing activities of daily living.

Multidirectional instability is described as global shoulder laxity that can be congenital, acquired, or both, primarily due to combination of a redundant inferior capsular pouch, lax ligaments about the shoulder, and weakened musculotendinous structures. [2] [16] Congenital laxity often occurs in multiple joints of the body, such as in Marfan syndrome. Acquired laxity is found in competitive athletes, specifically gymnasts and swimmers. The combination of both is found in individuals who have baseline laxity who become symptomatic after mild to moderate trauma. Diagnosis is largely by clinical examination; however, magnetic resonance imaging can help evaluate the presence and extent of a traumatic component. The mainstay of treatment is nonoperative management focusing on physical therapy that involves strength and neuromuscular coordination of the rotator cuff, deltoid, and scapula.[16] Operative management is reserved for those refractory to conservative measures. The open inferior capsular shift, as originally described by Neer and Foster,[13] has historically been the operative treatment of choice. With advances in arthroscopic techniques, the open procedure is used less frequently.

Most patients present as young adults and can have bilateral symptoms. It is important to ascertain a family history of similar complaints to evaluate for congenital causes. A psychiatric history (i.e., intentional dislocators) may preclude individuals from surgery. [13] [16] Pain is invariably the most common presenting complaint. Symptoms are generally provoked by normal daily activities. Also, looseness or the sensation of the shoulder’s “slipping out” is a frequent complaint. Rarely, patients may complain of numbness, tingling, and weakness of the affected extremity.

The mainstay of diagnosis is physical examination. Basic shoulder examination includes inspection for muscle atrophy, palpation for any point tenderness, and active and passive range of motion to evaluate for shoulder biomechanics. As with any complete examination of the shoulder, the physician should evaluate the cervical spine. Signs of global ligamentous laxity, including elbow hyperextension, ability to touch the thumb to the forearm (

Fig. 13-1

), and patellar subluxation, are frequently observed.

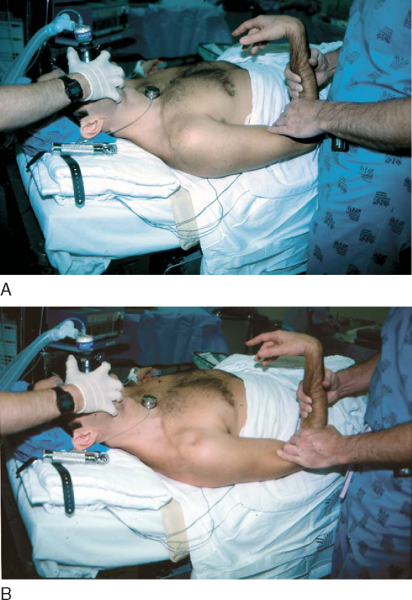

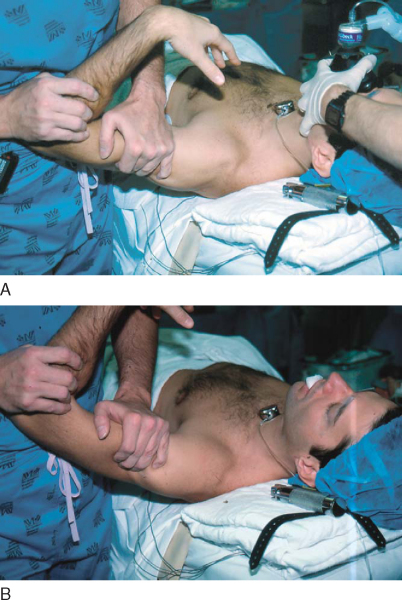

A sulcus or apprehension sign is commonly present (

Fig. 13-2

). We also use the load-shift test to quantify both anterior and posterior laxity (

Fig. 13-3

).[10] This is done by placing the shoulder off the edge of the table in 90 degrees of abduction and applying an anterior and posterior trans lational force. It is graded as minimal translation (trace), humeral head translation to the rim (1+), translation over the rim with spontaneous reduction (2+), and dislocation (3+). The contralateral shoulder should be evaluated for laxity as well. Additional maneuvers to demonstrate increased translation include the Fukuda test and the jerk test.[16]

|

|

|

|

Figure 13-3 |

Multidirectional instability typically can be diagnosed clinically. However, plain radiographs can be obtained to rule out bone abnormalities, such as a bony Bankart or Hill-Sachs lesion. Computed tomography or magnetic resonance arthrography can be used to evaluate capsular volume.

Indications and Contraindications

Conservative management remains the treatment of choice. Initial management should include a period of immobilization and anti-inflammatory drugs. It is thought that multidirectional instability is due in part to stretching of the static shoulder stabilizers. Therefore, treatment should initially involve strengthening of the shoulder stabilizers, including the rotator cuff muscles and deltoid. Conditioning of the back muscles and the scapular stabilizers is also important for stability.[2] A change in lifestyle to limit pain-provoking activities such as overhead work is recommended. A formal two-phase rehabilitation program including Thera-Band exercises and light weights, focused on strengthening of the rotator cuff and deltoid muscles, has also been described.[4]

The primary indication for operative treatment is a failure of conservative management with persistent pain. [2] [6] [12] [13] [16] Conservative management is likely to fail in patients with unilateral involvement, difficulties performing activities of daily living, and higher grades of laxity on initial examination.[12] Contraindications to surgical treatment include noncompliance during a trial of conservative management, voluntary dislocators, and patients with psychiatric abnormalities. [5] [13] A poor prognostic indicator, particularly in athletes, is bilateral multidirectional instability requiring bilateral repair.[5]

Historically, surgical options have included thermal capsular shrinkage and glenoid osteotomy.[16] However, the open inferior capsular shift as described by Neer and Foster is the most commonly performed open procedure, with arthroscopic techniques gaining increasing popularity. The inferior capsular shift procedure reduces total capsular volume by releasing the inferior capsule and shifting it superiorly. [6] [13]

We prefer an interscalene block with sedation, reserving general anesthesia for inadequate block or sedation. Local anesthesia with infiltration of the skin and subcutaneous tissue is also used. The patient can be positioned supine or 20 degrees upright. Although some authors state that all inferior capsular shift procedures can be performed through an anterior approach,[6] others believe the approach should be determined by the primary direction of instability, [5] [13] [14] as described by the patient or determined by physical examination. If anterior instability is the primary component, we prefer an anterior approach in the supine position with a rolled towel positioned between the thoracic spine and medial border of the scapula.[8] If posterior instability is the primary component, a posterior approach is preferred, keeping in mind that a separate anterior incision may be needed if a Bankart lesion is identified intraoperatively. An examination under anesthesia is performed to confirm surgical decision-making. [10] [13] [16]

A thorough examination under anesthesia is performed to document motion and direction of instability before surgical stabilization. In addition to a general shoulder examination, an assessment of the degree of capsular redundancy can be accomplished by the sulcus test. This is performed by applying downward traction to the adducted arm (see

Fig. 13-2

), followed by assessing the degree of downward displacement in varying degrees of external rotation.[10] Persistent inferior displacement with downward traction (sulcus sign) with external rotation may suggest a contribution from the rotator interval. The load-shift test assesses the relative degree of anterior or posterior instability (see

Fig. 13-3

). Finally, diagnostic arthroscopy can aid in identifying associated Bankart or posterior labral lesions before continuing with the open procedure.

| • | Acromion | |

| • | Coracoid process | |

| • | Axillary fold |

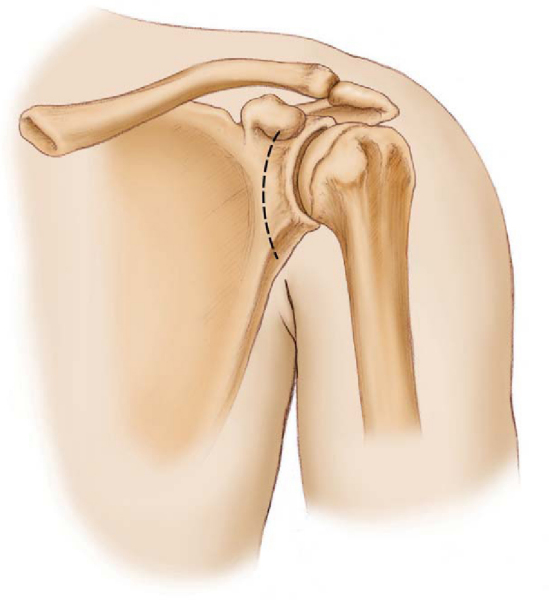

Anterior Approach (

Box 13-1

)

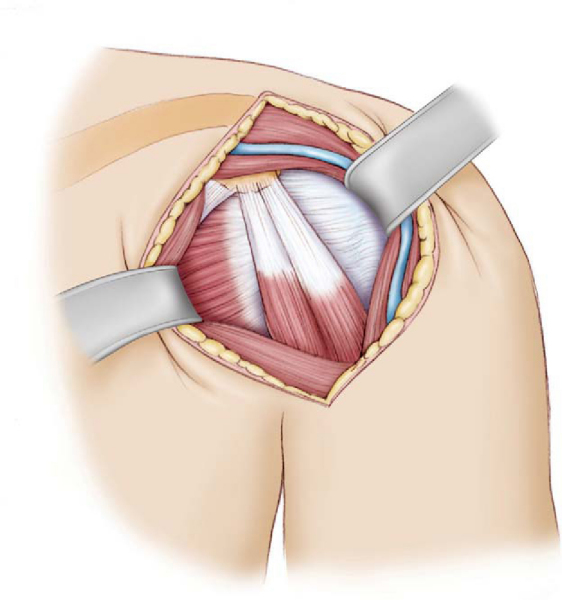

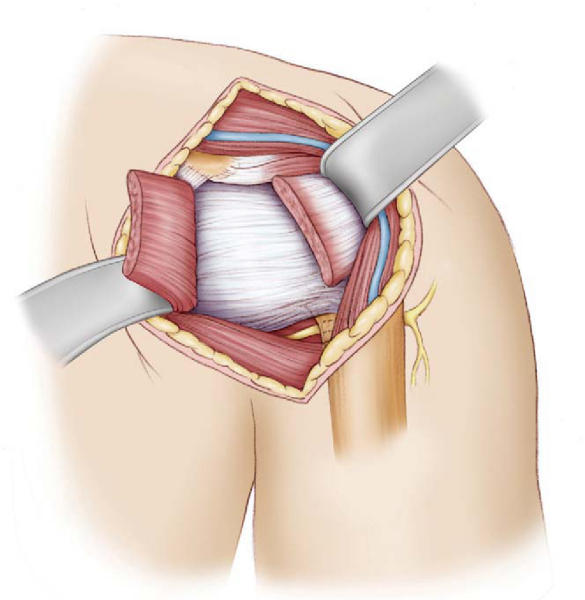

The landmark for this approach is the coracoid process. The technique for the inferior capsular shift is similar to that used in the original series by Neer and Foster.[13] Various modifications have been made subsequent to that. The incision is made from the tip of the coracoid process to the axilla along the deltopectoral groove (

Fig. 13-4

).[9] Develop the deltopectoral interval medial to the cephalic vein, retracting the deltoid laterally and the pectoralis medially (

Fig. 13-5

). Divide the clavipectoral fascia and retract the coracobrachialis and the short head of the biceps medially. Identify and ligate the anterior humeral circumflex vessels located at the inferior border of the tendinous portion of the subscapularis. Place the arm in external rotation and divide the subscapularis 1 cm medial to its insertion, carefully developing a plane between the subscapularis tendon and capsule. Tag the proximal end and retract medially (

Fig. 13-6

). In athletes that rely heavily on upper extremity function, consider use of a subscapularis-splitting approach.[3] It has been shown to have a higher rate of return to professional-level activity. Close the rotator interval between the superior and middle glenohumeral ligaments with absorbable suture if a lesion is present. Identify and protect the axillary nerve as it crosses near the inferior border of the capsule.

| Surgical Steps: Anterior Approach | |||||||||||||||

|

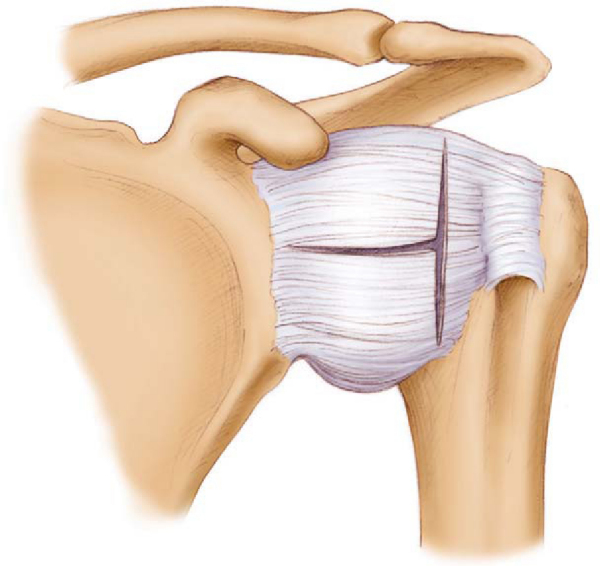

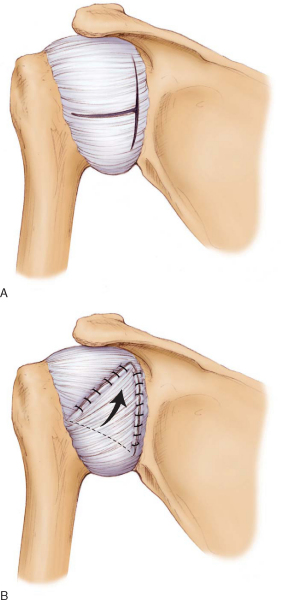

Make a T-shaped capsulotomy, starting the horizontal limb medially between the superior and middle glenohumeral ligaments,[10] extending the incision inferolaterally toward the humeral neck (

Fig. 13-7

). Place the arm in external rotation and release the inferior capsule from the humeral neck, proceeding posteriorly. Tag the inferior flap at its corner. One technique to assess adequate reduction in capsular volume is to place a finger in the inferior capsular pouch and pull the capsular stitch superiorly until the surgeon’s finger is extruded. If it does not extrude, then extend the capsular incision around the humeral neck even farther posteriorly. [10] [14] Inspect the joint for any loose bodies or labral disease (

Fig. 13-8

).

3. Preparing the Reattachment Site

With a curet or high-speed bur, decorticate the anterior and inferior sulcus of the humeral neck to obtain a bleeding bed of cancellous bone.

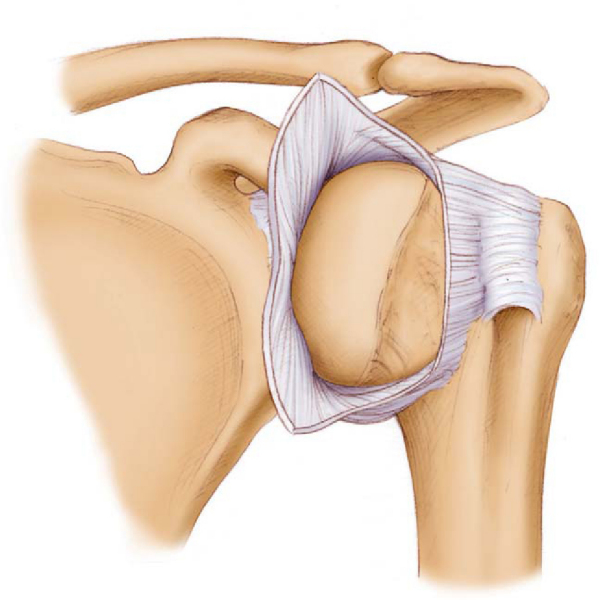

Suture the capsular flap to the stump of the subscapularis tendon and to the part of the capsule that remains on the humerus. Alternatively, the capsule can be sutured directly into the humerus with the aid of suture anchors. Select the appropriate tension on the flap to eliminate the inferior pouch and reduce the posterior capsular redundancy. Place the arm in 40 degrees of abduction and 40 degrees of external rotation. Advance the inferior flap superiorly such that it is repaired to the bleeding bed of cancellous bone and to the lateral aspect of capsule (

Fig. 13-9

). Use nonabsorbable sutures in a pants-over-vest fashion.[6] The superior flap is advanced distally and laterally and repaired in a similar fashion to reinforce the anterior capsule (

Fig. 13-10

). This also allows the middle glenohumeral ligament to reinforce the capsule anteriorly.

|

|

|

|

Figure 13-9 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 13-10 |

5. Subscapularis Repair and Closure

The subscapularis tendon is brought over the capsular shift and then reattached to its usual location with multiple nonabsorbable sutures. Close the deltopectoral interval with absorbable sutures and the skin and subcutaneous tissues in usual fashion.

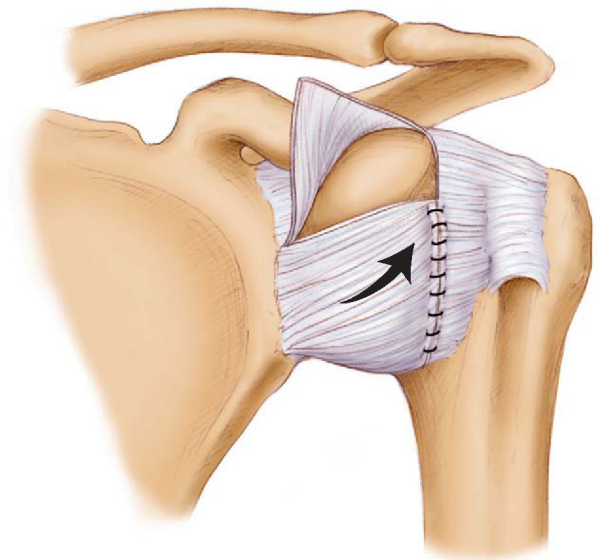

An alternative to the humeral-based capsular incision is the glenoid-based capsulotomy. Similar concepts apply in regard to capsular advancement (

Fig. 13-11

). However, the flaps are attached to the glenoid margin, commonly with suture anchors. [1] [7] [11]

|

|

|

|

Figure 13-11 (Redrawn from Bowen M, Warren R. Surgical approaches to posterior instability of shoulder. Oper Tech Sports Med 1993;1:301-310.) |

In our experience, most cases of multidirectional instability can be treated with the anterior approach as patients typically present with anterior instability as the primary component. Cooper and Brems[6] advocate use of the anterior approach for all cases, including those with posterior instability as the primary component. We advocate choosing the approach on the basis of the direction of the primary instability. Refer to

Chapter 12

for further details of the posterior approach for instability surgery.

Postoperative care is integral to the healing process. We base our method of immobilization on the primary direction of instability. For anterior instability, patients can typically be discharged in a sling; for posterior instability, we advocate use of a Gunslinger brace. After a 6-week period of immobilization, gradual range-of-motion exercises are initiated according to a strict protocol; the concern is that ambitious patients will do too much too early, resulting in recurrent instability. During weeks 6 through 10, below-the-shoulder exercises are conducted, limiting external rotation to 45 degrees. Beginning in week 10, a stretching program is initiated, focusing on forward elevation and external rotation. At weeks 14 to 16, deltoid and rotator cuff strengthening is added, followed by scapular stabilization exercises at weeks 18 to 20. Contact sports are typically allowed only after complete restoration of strength and condition, usually about 6 months after surgery.

Reported complications include recurrent instability, persistent symptoms of apprehension, axillary nerve neurapraxia, and infection.

Historical results of the open procedure have been good. However, with increasing success of arthroscopic techniques, the role of the open procedure is diminishing. In Neer and Foster’s original series,[13] 39 of 40 shoulders had good results. Cooper and Brems[6] reported that 39 of 48 shoulders functioned well without instability after up to 6 years of followup. Four shoulders had recurrent instability, and the patients were subjectively dissatisfied. The authors also stated that if failure occurs, it tends to happen early in the postoperative period. Van Tankeren et al[15] reported excellent results based on objective scores in 14 of 17 shoulders at a mean followup of 39 months. Pollock et al[14] described good or excellent results in 46 of 49 shoulders with an average followup of more than 5 years (

Table 13-1

).

| Author | Successful Results/No. of Shoulders | Followup | Recurrent Instability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neer and Foster[13] (1980) | 39/40 | Variable[*] | 3% |

| Cooper and Brems[6] (1992) | 39/43 | 2-6 years | 9% |

| Bak et al[3] (2000) | 24/26 | Median: 54 months | 8% |

| Pollock et al[14] (2000) | 46/49 | Average: 61 months | 4% |

| Choi and Ogilvie-Harris[5] (2002) | 48/53 | Average: 42 months | 9% |

| Van Tankeren et al[16] (2002) | 14/17 | Mean: 39 months | 6% † |

| * | Less than 12 months (8 shoulders), 12 to 24 months (15 shoulders), and more than 24 months (17 shoulders). |

| † | Without any associated injuries. |

1.

Altchek D, Warren R, Skyhar M, Ortiz G: T-plasty modification of the Bankart procedure for multidirectional instability of the anterior and inferior types.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1991; 73:105-112.

2.

An Y, Friedman R: Conservative management of shoulder injuries: multidirectional instability of the glenohumeral joint.

Orthop Clin North Am 2000; 31:275-285.

3.

Bak K, Spring B, Henderson I: Inferior capsular shift procedure in athletes with multidirectional instability based on isolated capsular and ligamentous redundancy.

Am J Sports Med 2000; 28:466-471.

4.

Burkhead W, Rockwood C: Treatment of instability of the shoulder with an exercise program.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992; 74:890-896.

5.

Choi C, Ogilvie-Harris D: Inferior capsular shift operation for multidirectional instability of the shoulder in players of contact sports.

Br J Sports Med 2002; 36:290-294.

6.

Cooper R, Brems J: The inferior capsular shift procedure for multidirectional instability of the shoulder.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992; 74:1516-1521.

7.

Cordasco F, Pollock R, Flatow E, Bigliani L: Management of multidirectional instability.

Oper Tech Sports Med 1993; 1:293-300.

8.

Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P: The shoulder.

Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach,

Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1994:2-49.

9.

Leslie J, Ryan T: The anterior axillary incision to approach the shoulder joint.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1962; 44:1193-1196.

10.

Levine W, Prickett W, Prymka M, Yamaguchi K: Repair of athletic shoulder injuries: treatment of the athlete with multidirectional shoulder instability.

Orthop Clin North Am 2001; 32:475-484.

11.

Marquardt B, Potzl W, Witt K, Steinbeck J: A modified capsular shift for atraumatic anterior-inferior shoulder instability.

Am J Sports Med 2005; 33:1011-1015.

12.

Misamore G, Sallay P, Didelot W: A longitudinal study of patients with multidirectional instability of the shoulder with seven- to ten-year followup.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005; 14:466-470.

13.

Neer C, Foster C: Inferior capsular shift for involuntary inferior and multidirectional instability of the shoulder.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1980; 60:897-908.

14.

Pollock R, Owens J, Flatow E, Bigliani L: Operative results of the inferior capsular shift procedure for multidirectional instability of the shoulder.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000; 82:919-928.

15.

Schenk T, Brems J: Multidirectional instability of the shoulder: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management.

J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1998; 6:65-72.

16.

Van Tankeren E, Malefijt M, Van Loon C: Open capsular shift for multidirectional shoulder instability.

Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2002; 122:447-450.