Burners (Stingers)

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Burners (Stingers)

Burners (Stingers)

Michael K. Shindle MD

Marc Urquhart MD

Description

-

Burners (also termed “stingers”) are traction injuries that result in a neurapraxia of the brachial plexus.

-

Patients typically report pain that

radiates into the shoulder and down the arm to the hand, which is

usually described as a “dead arm.” -

These injuries are common in tackling sports and usually occur in teenagers and young adults.

-

One of the most common injuries in football

-

Usually associated weakness of shoulder abduction (deltoid), elbow flexion (biceps), and external humeral rotation (spinati) (1)

-

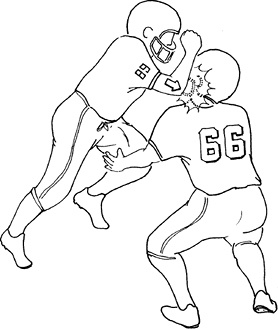

The brachial plexus injury typically involves only the upper trunk (2) (Fig. 1).

Epidemiology

Males are affected more often than are females.

Risk Factors

-

High-impact sports

-

Motorcycle crashes

-

Cervical stenosis may predispose an

athlete to a burner syndrome because of concomitant foraminal narrowing

with nerve root compression.

Etiology

-

Typically secondary to ipsilateral shoulder depression with lateral neck deviation to the contralateral side (3) (Fig. 1)

-

A direct blow to the supraclavicular area may occur in football and other contact sports, as well as in motorcycle accidents.

Associated Conditions

-

Horner syndrome

-

Suprascapular nerve compression

Fig. 1. Burners and stingers are produced by a downward blow to the shoulder or by a lateral force to the hand and neck.

Fig. 1. Burners and stingers are produced by a downward blow to the shoulder or by a lateral force to the hand and neck.

Signs and Symptoms

-

The distribution of symptoms depends on the level of the brachial plexus injury.

-

Transient numbness or tingling may be present.

-

Weakness of shoulder abduction (deltoid), elbow flexion (biceps), and external humeral rotation (spinati) may occur.

Physical Exam

-

Sideline evaluation should include:

-

Palpation of the cervical spine for

tenderness and cervical ROM testing: Cervical tenderness or painful or

limited ROM are red flags for a more serious problem. -

A complete but brief neurologic

examination of all four extremities: Sensation and movement may be

checked by having the patient flex and extend each joint; test

sensation on anterior and posterior surfaces of each limb segment. -

Manual muscle testing in the affected

upper extremity: Arm weakness with decreased sensation may be present,

but athletes usually have a normal examination by the time they reach

the sideline (4). -

Testing for tenderness in the brachial

plexus: Tinel sign in the supraclavicular fossa indicates damage to at

least 1 nerve root.

-

Tests

Lab

Electromyographic and nerve conduction velocity studies

should be obtained if no recovery of neurologic function occurs in 2–3

weeks (rare).

should be obtained if no recovery of neurologic function occurs in 2–3

weeks (rare).

Imaging

-

Radiography:

-

Plain radiographs of the cervical spine,

including active flexion and extension views to look for cervical

instability and oblique views to visualize the cervical nerve root

foramen (5). -

Scapular AP and lateral views plus axillary views of the shoulder

-

-

MRI of the cervical spine for patients with recurrent stingers or persistent neurologic deficit

Differential Diagnosis

-

Cervical spine injury or stenosis

-

Thoracic outlet syndrome

-

Long thoracic nerve palsy

-

Suprascapular nerve compression

General Measures

-

Observation and serial evaluations should be performed.

-

Most patients recover within minutes.

-

Return to play is allowed when full

strength has returned, all neurologic signs and symptoms have resolved,

and cervical ROM is pain free. -

Patients with recurrent or prolonged (hours to weeks) burner syndrome mandate additional evaluation, including:

-

AP, lateral, oblique, and odontoid views of the cervical spine for assessment of cervical stenosis (6).

-

If those radiographs are negative, then flexion–extension views to identify ligamentous instability

-

-

The affected extremity may be placed in a sling for comfort, as needed.

-

The patient should be restricted from sports until the symptoms have resolved and any needed workup is complete.

-

If stingers are recurrent, a change in sport should be considered.

Special Therapy

Physical Therapy

An aggressive neck and shoulder strengthening program should be initiated.

Medication (Drugs)

Analgesics may be taken, if needed.

Surgery

In general, surgery is not indicated.

P.47

Prognosis

-

The prognosis is generally poor for patients with supraclavicular injuries and patients with complete neurologic deficits.

-

The prognosis is more favorable for patients with infraclavicular injuries or incomplete neurologic deficits.

Complications

-

Incomplete recovery

-

Muscle weakness or wasting

-

Pain

References

1. Feinberg JH. Burners and stingers. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2000;11:771–784.

2. Weinberg J, Rokito S, Silber JS. Etiology, treatment, and prevention of athletic “stingers.” Clin Sports Med 2003;21:493–500.

3. Vaccaro AR, Watkins B, Albert TJ, et al. Cervical spine injuries in athletes: current return-to-play criteria. Orthopaedics 2001;24:699–703.

4. Safran

MR. Nerve injury about the shoulder in athletes, part 2: long thoracic

nerve, spinal accessory nerve, burners/stingers, thoracic outlet

syndrome. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:1063–1076.

MR. Nerve injury about the shoulder in athletes, part 2: long thoracic

nerve, spinal accessory nerve, burners/stingers, thoracic outlet

syndrome. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:1063–1076.

5. Kelly JD, IV, Aliquo D, Sitler MR, et al. Association of burners with cervical canal and foraminal stenosis. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:214–217.

6. Levitz

CL, Reilly PJ, Torg JS. The pathomechanics of chronic, recurrent

cervical nerve root neurapraxia. The chronic burner syndrome. Am J Sports Med 1997;25:73–76.

CL, Reilly PJ, Torg JS. The pathomechanics of chronic, recurrent

cervical nerve root neurapraxia. The chronic burner syndrome. Am J Sports Med 1997;25:73–76.

Additional Reading

Fagan KM. Head and neck injuries. In: Andrews JR, Clancy WG, Jr, Whiteside JA, eds. On-Field Evaluation and Treatment of Common Athletic Injuries. St. Louis: Mosby, 1997:1–15.

Torg JS. Cervical spine injuries. In: Garrick JG, ed. Orthopaedic Knowledge Update: Sports Medicine 3. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2004:3–18.

Zarins B, Prodromos CC. Shoulder injuries in sports. In: Rowe CR, ed. The Shoulder. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1988:411–433.

Codes

ICD9-CM

767.6 Injury to brachial plexus

Patient Teaching

-

Proper tackling technique should be taught.

-

The motion and position that produce brachial plexus stretch should be explained.

-

Patients should avoid impact on the top of the shoulder or the side of the neck.

Prevention

-

Physical therapy with emphasis on a neck-strengthening program

-

High-profile shoulder pads or a cowboy collar to limit the extent of lateral flexion and extension

-

Education about proper blocking and tackling techniques

FAQ

Q: In the stinger syndrome, weakness most commonly occurs during strength testing of which muscles?

A:

In most cases, this injury involves the upper trunk (C5, C6) of the

brachial plexus. Thus, weakness may include the deltoid (C5), biceps

(C5, C6), supraspinatus (C5, C6), and infraspinatus muscles (C5, C6).

In most cases, this injury involves the upper trunk (C5, C6) of the

brachial plexus. Thus, weakness may include the deltoid (C5), biceps

(C5, C6), supraspinatus (C5, C6), and infraspinatus muscles (C5, C6).

Q: What criteria should be used to decide if an athlete can return to play?

A:

Most athletes have full recovery within minutes. If full strength has

returned and all neurologic signs and symptoms have resolved, return to

play is allowed. More prolonged symptoms and/or 3 or more previous

episodes of the stinger/burner syndrome should prohibit return to play

until additional evaluation is performed.

Most athletes have full recovery within minutes. If full strength has

returned and all neurologic signs and symptoms have resolved, return to

play is allowed. More prolonged symptoms and/or 3 or more previous

episodes of the stinger/burner syndrome should prohibit return to play

until additional evaluation is performed.

Q: What condition may predispose an athlete to develop the burner/stinger syndrome?

A:

Cervical stenosis may predispose an athlete to experiencing a burner

syndrome because of concomitant foraminal narrowing with nerve root

compression.

Cervical stenosis may predispose an athlete to experiencing a burner

syndrome because of concomitant foraminal narrowing with nerve root

compression.