The Hip

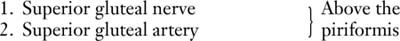

surgical procedures performed in orthopaedics. Total joint replacement

for degenerative joint disease has revolutionized the lives of millions

of patients. Open approaches to the hip joint are also required for

hemiarthroplasties, tumor surgery, and for the treatment of infection

around the hip joint.

the most common approach for total hip replacement, has many variations

because of the different requirements of the several prosthetic designs

that can be inserted. The standard anterolateral approach is described;

readers are advised to consult the original papers of the designers of

the arthroplasty before performing a particular joint replacement. The posterior approach,

which is used extensively for hemiarthroplasty as well as for total hip

joint replacement, is probably the most common approach performed

around the hip joint. It is both safe and easy to perform with only one

assistant. The medial approach is rarely used, and then mainly for local procedures on the lesser trochanter and surrounding bone.

|

|

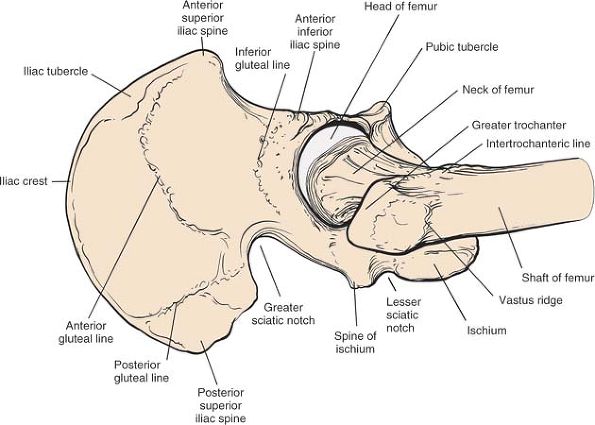

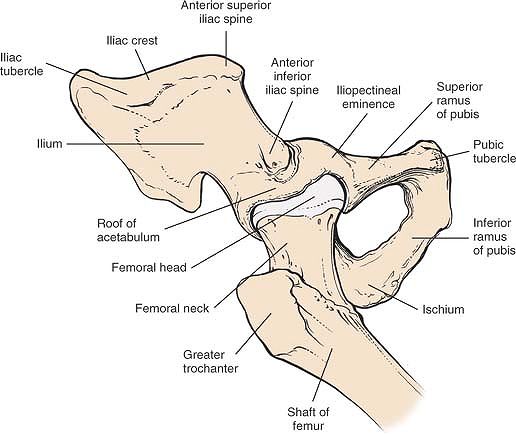

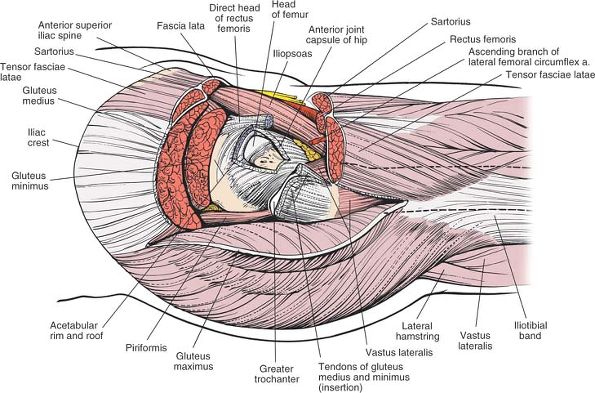

Figure 8-1 The intermuscular intervals used in the anterior, anterolateral, and posterior approaches to the hip.

|

increased in popularity. Most of these techniques utilize the classical

approaches described in this book. The length of the skin incision and

the underlying dissection is reduced. Minimal access surgery can create

less soft-tissue damage, but the visualization of the structures is

necessarily less. The techniques, therefore, are potentially more

hazardous, and an understanding of the underlying anatomy is important.

In addition, imaging may be indicated to ensure correct implant

position.

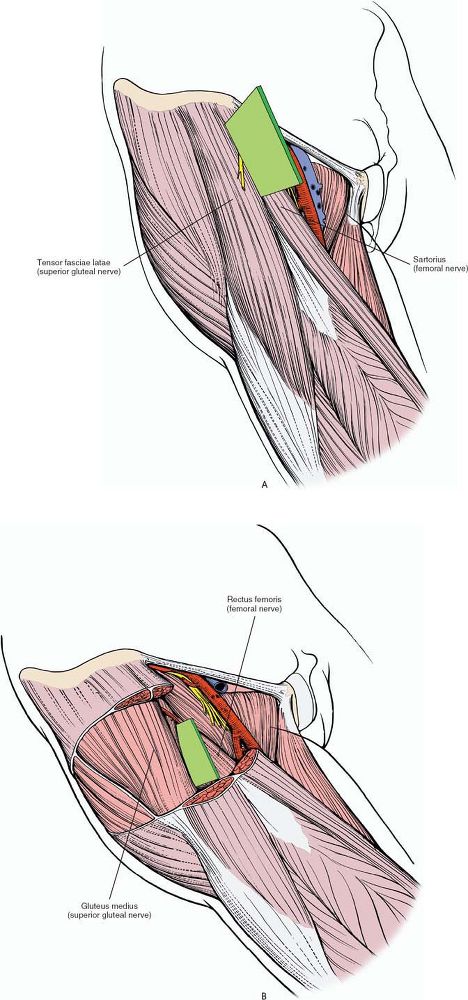

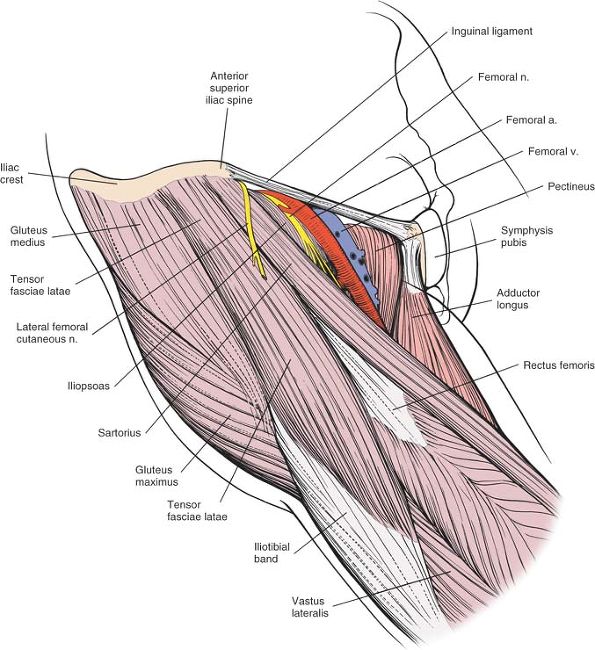

the muscular intervals that surround the joint. The anterior approach

uses the interval between the sartorius and the tensor fasciae latae;

the anterolateral approach uses the interval between the tensor fasciae

latae and the gluteus medius; the posterior approach gains access

either through the interval between the gluteus medius and the gluteus

maximus or by splitting the gluteus maximus; and the medial approach

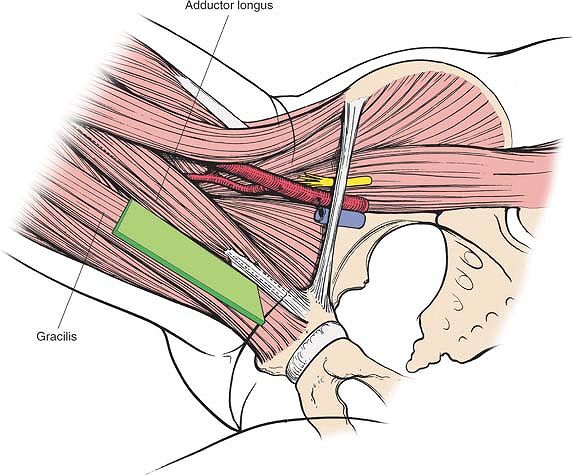

exploits the interval between the adductor longus and the gracilis (Fig. 8-1).

approaches. Because the anterior and anterolateral approaches share so

much anatomy, they are grouped together. The anatomy for the posterior

and medial approaches follows the appropriate approach.

approach, gives safe access to the hip joint and ilium. It exploits the

internervous plane between the sartorius (femoral nerve) and the tensor

fasciae latae (superior gluteal nerve) to penetrate the outer layer of

the joint musculature. Its uses include the following:

-

Open reduction of congenital dislocations of the hip when the dislocated femoral head lies anterosuperior to the true acetabulum7

-

Synovial biopsies

-

Intraarticular fusions

-

Total hip replacement

-

Hemiarthroplasty

-

Excision of tumors, especially of the pelvis

-

Pelvic osteotomies

completely as other incisions unless muscles are extensively stripped

off the pelvis.

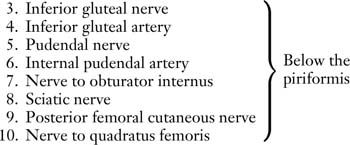

approach is to be used for pelvic osteotomy, place a small sandbag

under the affected buttock to push the affected hemipelvis forward (Fig. 8-2).

is subcutaneous and is easily palpable in thin patients. In obese

patients, it is covered by adipose tissue and is more difficult to

find. You can locate it most easily if you bring your thumbs up from

beneath the bony protuberance.

subcutaneous and serves as a point of origin and insertion for various

muscles. However, none of these muscles cross the bony crest; it

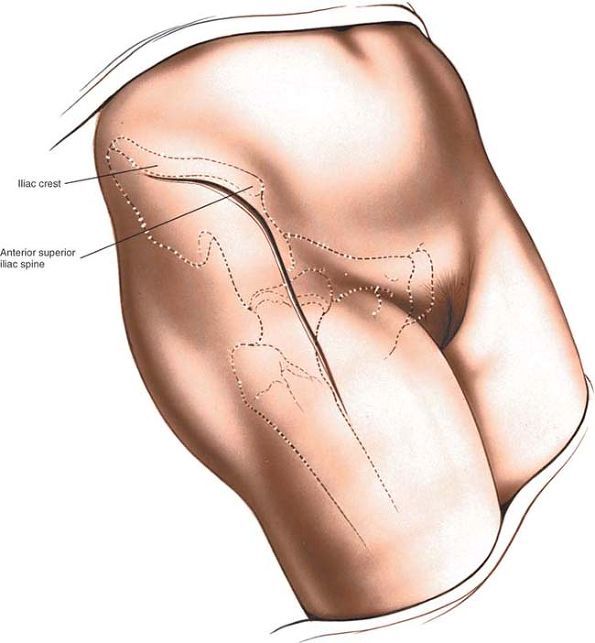

remains available for palpation (Fig. 8-3).

iliac crest to the anterior superior iliac spine. From there, curve the

incision down so that it runs vertically for some 8 to 10 cm, heading

toward the lateral side of the patella (see Fig. 8-3).

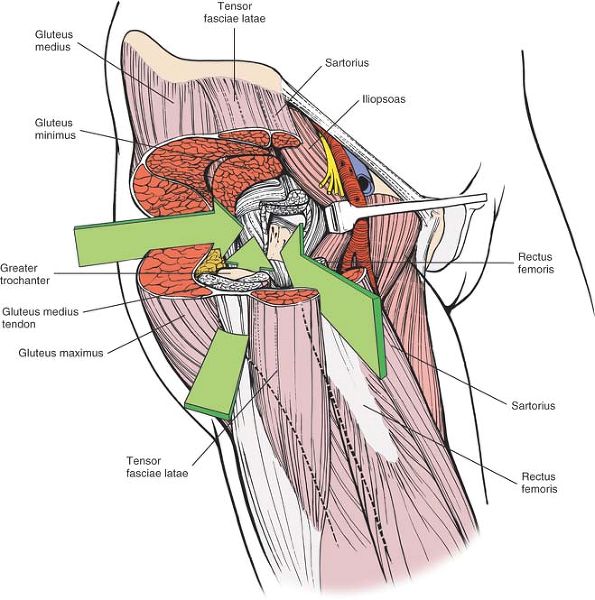

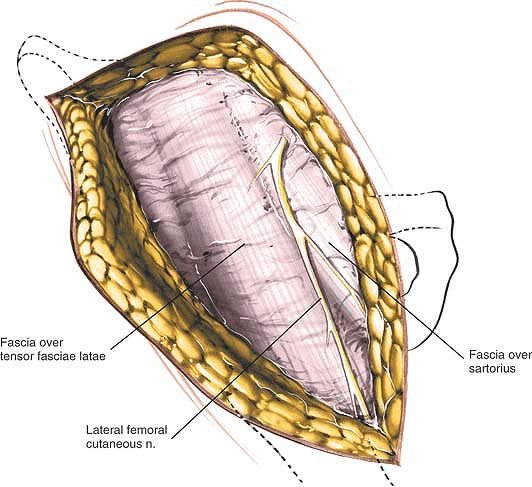

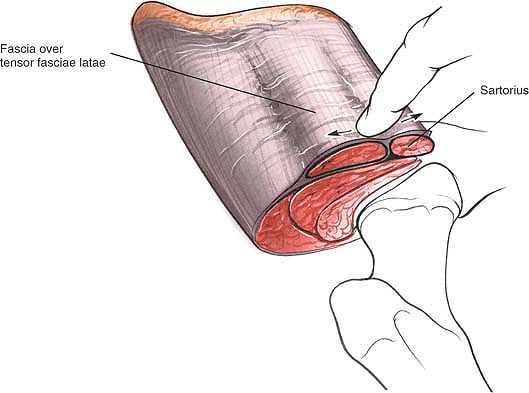

muscle, making it more prominent. Identify the gap between the tensor

fasciae latae and the sartorius by palpation (Fig. 8-6).

The best place to find it is some 2 to 3 inches below the anterior

superior iliac spine, since the fascia that covers both muscles just

below the spine makes the interval difficult to define at its highest

point. With scissors, carefully dissect down through the subcutaneous

fat along the intermuscular

interval.

Avoid cutting the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (lateral cutaneous

nerve of the thigh), which pierces the deep fascia of the thigh close

to the intermuscular interval (Fig. 8-5).

|

|

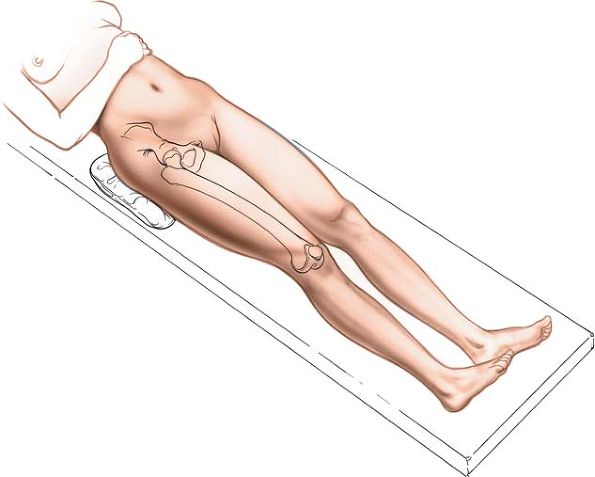

Figure 8-2 Position of the patient on the operating table for the anterior approach to the hip.

|

|

|

Figure 8-3

Make a longitudinal incision along the anterior half of the iliac crest to the anterior superior iliac spine. From there, curve the incision down so that it runs vertically for some 8 to 10 cm. |

|

|

Figure 8-4 (A) The internervous plane lies between the sartorius (femoral nerve) and the tensor fasciae latae (superior gluteal nerve). (B) The deeper internervous plane lies between the rectus femoris (femoral nerve) and the gluteus medius (superior gluteal nerve).

|

fascia latae. Staying within the fascial sheath of this muscle will

protect you from damaging the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve because

the nerve runs over the fascia of the sartorius. Retract the sartorius

upward and medially and the tensor fascia latae downward and laterally (Fig. 8-7).

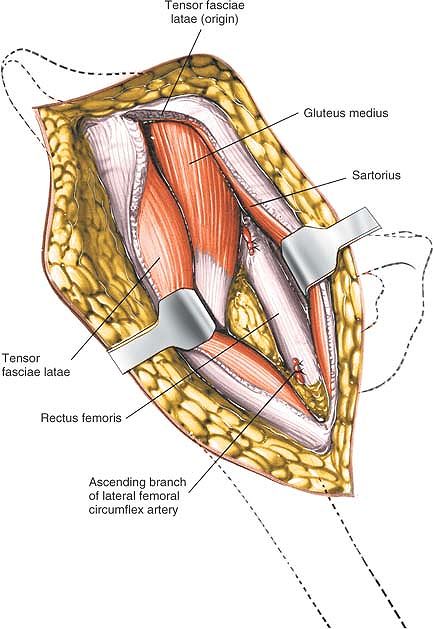

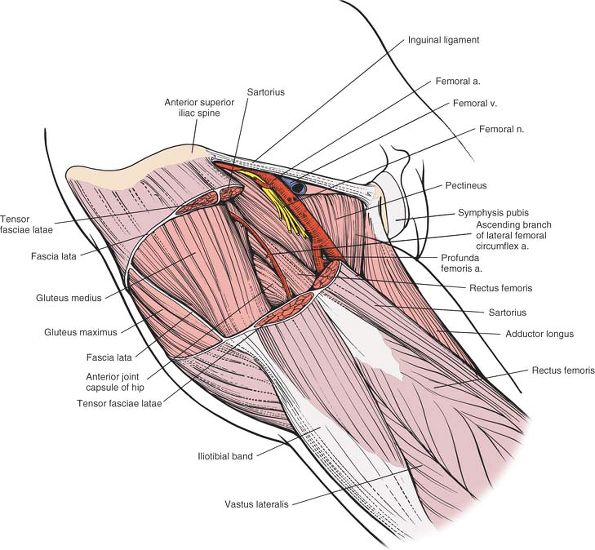

develop the internervous plane. The large ascending branch of the

lateral femoral circumflex artery crosses the gap between the two

muscles below the anterior superior iliac spine. It must be ligated or

coagulated.

brings you on to two muscles of the deep layer of the hip musculature,

the rectus femoris (femoral nerve)

and the gluteus medius (superior gluteal nerve) (Fig. 8-8).

|

|

Figure 8-5

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh) pierces the deep fascia close to the intermuscular interval between the tensor fasciae latae and the sartorius. |

|

|

Figure 8-6 Identify the gap between the tensor fasciae latae and the sartorius by palpation.

|

|

|

Figure 8-7

Incise the deep fascia on the medial side of the tensor fasciae latae. Retract the sartorius upward and medially and the tensor fascia downward and laterally. |

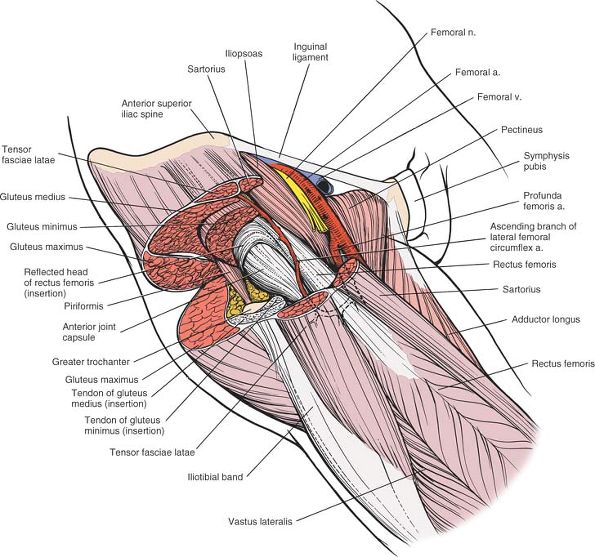

head, from the anterior inferior iliac spine, and the reflected head,

from the superior lip of the acetabulum. The reflected head also takes

origin from the anterior capsule of the hip joint. It is intimate with

the capsule, making dissection between the two structures difficult.

rectus femoris and the gluteus medius, palpate the femoral artery. The

femoral pulse is well medial to the intermuscular interval; if you

dissect near it, you are out of plane. Detach the rectus femoris from

both its origins and retract it medially. Retract the gluteus medius

laterally (Fig. 8-9).

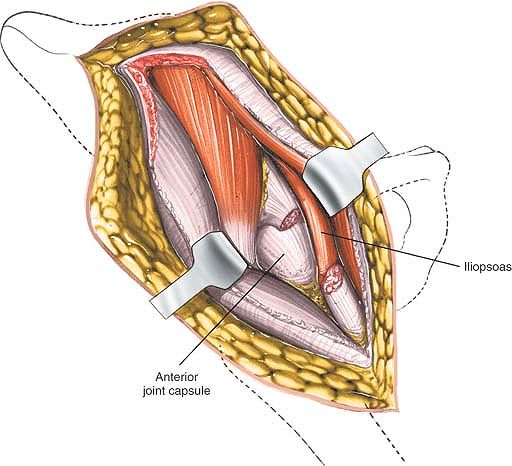

Inferomedially, you can see the iliopsoas as it approaches the lesser

trochanter: Retract it medially (Figs. 8-10 and 8-11).

The iliopsoas is often partly attached to the inferior aspect of the

hip joint capsule and must be released from it. Inferolaterally, the

shaft of the femur lies under cover of the vastus lateralis.

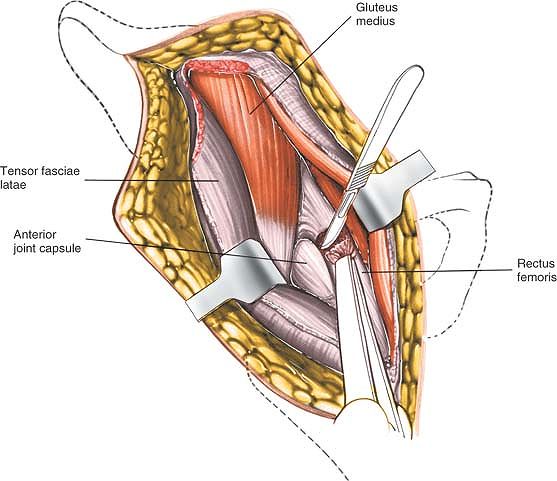

capsule on stretch; define the capsule with blunt dissection. Incise

the hip joint capsule as the surgery requires, with either a

longitudinal or a T-shaped capsular incision (Fig. 8-12). Dislocate the hip by external rotation after the capsulotomy.

reaches the thigh by passing over, behind, or through—usually over—the

sartorius muscle, about 2½ cm below the anterior superior iliac spine.

The nerve must be preserved when you incise the fascia between the

sartorius and the tensor fasciae latae; cutting it may lead to the

formation of a painful neuroma and may produce an area of diminished

sensation on the lateral aspect of the thigh (Fig. 8-14; see Fig. 8-5).

the nerve is well medial to the rectus femoris, it is not really in

danger unless you stray far out of plane to the wrong side of the

sartorius and the rectus femoris. If you lose the correct plane during

deep dissection, locate the femoral pulse by palpation. Within the

femoral triangle, the artery lies medial to the nerve (Figs. 8-15 and 8-16).

|

|

Figure 8-8

The deep layer of musculature, consisting of the rectus femoris and the gluteus medius, is now visible. The ascending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery must be ligated. |

|

|

Figure 8-9 Detach the rectus femoris from both its origins, the anterior inferior iliac spine and the superior lip of the acetabulum.

|

|

|

Figure 8-10 The hip joint capsule is now partly exposed. Retract the iliopsoas tendon medially.

|

|

|

Figure 8-11 The hip joint capsule is fully exposed. Detach the muscles of the ilium if further exposure is needed.

|

|

|

Figure 8-12 Incise the hip joint capsule.

|

|

|

Figure 8-13

Proximal extension of the wound exposes the ilium. Distal extension of the incision exposes the anterior aspect of the femur in the interval between the vastus lateralis and the rectus femoris. It may be necessary to split muscle fibers to actually expose the lateral aspect of the femur. |

|

|

Figure 8-14 Superficial view of the muscles of the anterior region of the hip, including the femoral triangle and its contents.

Sartorius. Origin. Anterior superior iliac spine and upper half of iliac notch. Insertion. Upper end of subcutaneous surface of tibia. Action. Flexor of thigh and knee and external rotator of hip. Nerve supply. Femoral nerve (L2-L4).

Tensor Fasciae Latae. Origin. From outer aspect of iliac crest between the anterior superior iliac spine and the tubercle of the iliac crest. Insertion. By iliotibial tract into Gerdy’s tubercle of the tibia. Action. Maintains stability of extended knee and extended hip. Nerve supply. Superior gluteal nerve.

|

|

|

Figure 8-15

The tensor fasciae latae, the sartorius, and the fascia lata have been resected on the anterior aspect of the hip to reveal the gluteus medius, the rectus femoris, and the ascending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery. The hip joint capsule is visible between these two muscles. Medially, note the relationship between the iliopsoas and the rectus femoris. |

Ligate or coagulate it when you separate the two muscles (see Figs. 8-8, 8-15, 8-16, 8-17, and 8-18).

|

|

Figure 8-16

The gluteus minimus, medius, and maximus have been resected to reveal the hip joint capsule and the reflected head of the rectus femoris. |

Detach the origins of the gluteus medius and minimus from the outer

wing of the ilium by blunt dissection. (This procedure is always

necessary during pelvic osteotomies.) Bleeding from the raw exposed

surface of the ilium can be controlled if you pack the wound with gauze

sponges. Individual bleeding points can be controlled by the

application of bone wax. There is no other way to stop bleeding.

iliac crest to expose that bone. In theory, the extension allows the

taking of bone graft, but it is rarely used.

incision downward along the anterolateral aspect of the thigh. Incise

the fascia lata in line with the skin incision; underneath it lies the

interval between the vastus lateralis and the rectus femoris. Try to

stay in the interval; you will have to split muscle fibers to expose

the anterior aspect of the femur. This extension gives excellent

exposure of the entire shaft of the femur (see Fig. 8-13).

the level of the hip joint to allow pelvis osteotomy. To obtain

visualization of the outer part of the ilium, gently strip the muscular

coverings from the bone at the level of the origin of the reflected

head of rectus. Using blunt instruments stay in contact with bone. This

dissection will lead you into the sciatic notch. Take great care that

any instrument inserted into the notch remains firmly on the bone,

since the sciatic nerve is also emerging through the notch. Detach the

straight head of the rectus femoris from the anterior inferior iliac

spine, and carefully lift off the iliacus muscle from the inside of the

pelvis, again sticking very carefully to the bone. A blunt instrument

will gradually lead you into the greater sciatic notch. At this stage,

both instruments should be in contact with each other and with the bone

of the sciatic notch. Retraction on both instruments will allow

visualization of the entire thickness of the pelvis at the level of the

top of the acetabulum, permitting an accurate osteotomy to be carried

out.

|

|

Figure 8-17

The iliopsoas tendon has been retracted medially; the rectus femoris has been resected and the joint capsule opened to reveal the joint. |

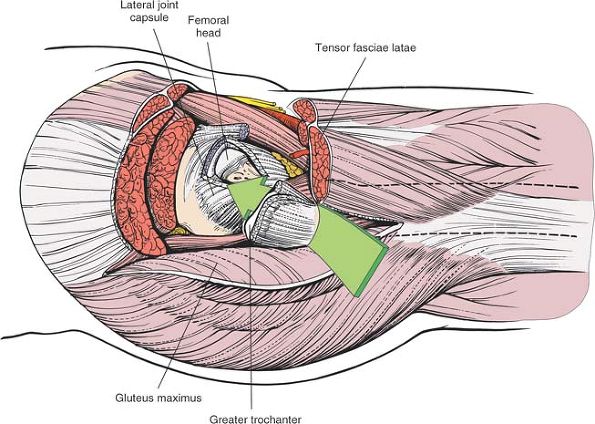

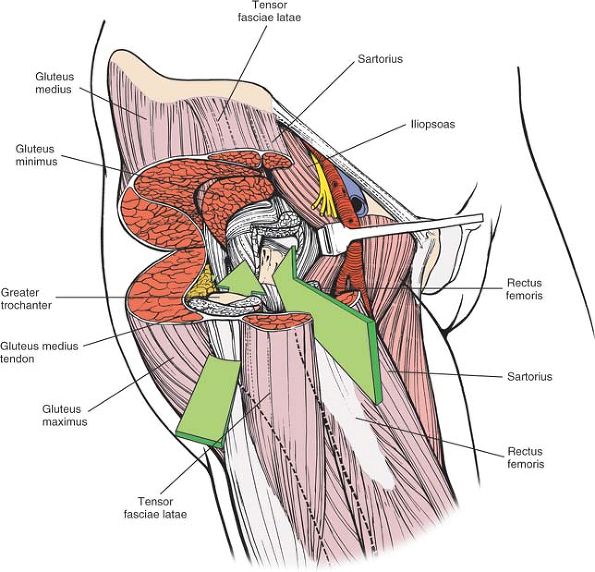

used for total joint replacements. It combines an excellent exposure of

the acetabulum with safety during reaming of the femoral shaft.

Popularized by Watson-Jones (D. Hirsh, personal communication, 1981)

and modified by Charnley,8 Harris,9 and Müller,10

it exploits the intermuscular plane between the tensor fasciae latae

and the gluteus medius. It also involves partial or complete detachment

of some or all of the abductor mechanism so that the hip can be

adducted during reaming of the femoral shaft and so that the acetabulum

can be more fully exposed (Fig. 8-19).

The two methods seem to offer different approaches, but they are

actually variations on a theme. The differences should not obscure the

fundamental fact that all anterolateral approaches exploit the same

intermuscular plane, between the tensor fasciae latae and the gluteus

medius.

|

|

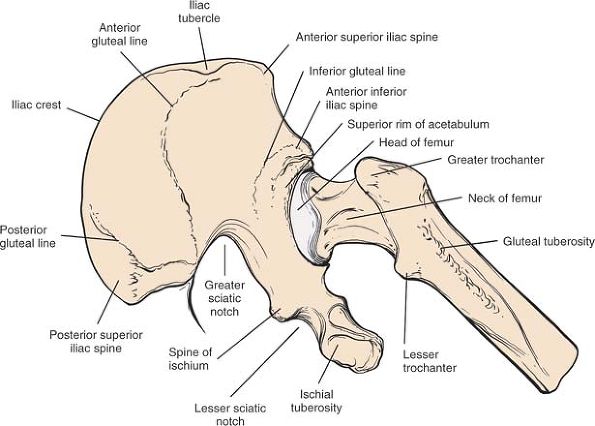

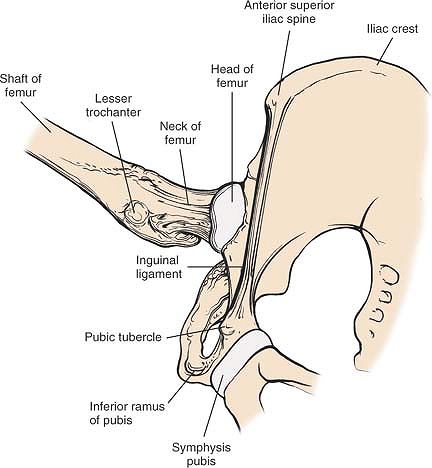

Figure 8-18 Osteology of the hip.

|

-

Total hip replacement10,11

-

Hemiarthroplasty

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of femoral neck fractures

-

Synovial biopsy of the hip

-

Biopsy of the femoral neck

Tilt the table away from you as the patient lies flat. Both maneuvers

allow the buttock skin and fat to fall posteriorly, away from the

operative plane, and lift the skin incision clear of the table, making

it easier to drape the patient. You must take this into account when

you insert the acetabular portion of a total joint replacement because

the guides used to position the acetabular prosthesis usually take the

ground as their reference plane.

|

|

Figure 8-19 The route of the anterolateral approach to the hip joint.

|

|

|

Figure 8-20

Position of the patient on the operating table for the anterolateral approach to the hip. Bring the greater trochanter to the edge of the table, and allow the buttocks, skin, and fat to fall posteriorly, away from the operative plane. |

|

|

Figure 8-21 Incision for the anterolateral approach to the hip.

|

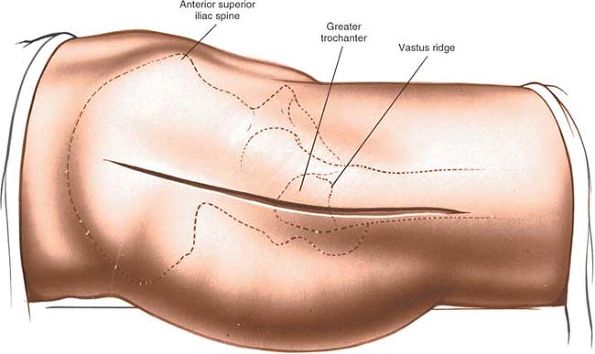

is subcutaneous. It is easy to palpate in all but the most obese

patients, who have a thick layer of adipose tissue covering it. To

palpate it, bring your thumbs up from beneath the bony protuberance.

a rough line that marks the fusion site of the greater trochanter to

the lateral surface of the shaft of the femur, is easiest to palpate

from distal to proximal. It is not palpable in obese patients.

lying across the opposite knee both to bring the trochanter into

greater relief and to move the tensor fasciae latae anteriorly. Make an

8- to 15-cm straight longitudinal incision centered on the tip of the

greater trochanter. The length of the incision relates to the size and

obesity of the patient as well as the surgeon’s experience. The

incision crosses the posterior third of the trochanter before running

down the shaft of the femur (see Fig. 8-21).

since the gluteus medius and the tensor fasciae latae have a common

nerve supply, the superior gluteal nerve. However, the superior gluteal

nerve enters the tensor fasciae latae very close to its origin at the

iliac crest; therefore, the nerve remains intact as long as the plane

between the gluteus medius and the tensor fasciae latae is not

developed up to the origins of both muscles from the ilium (see Fig. 8-19).

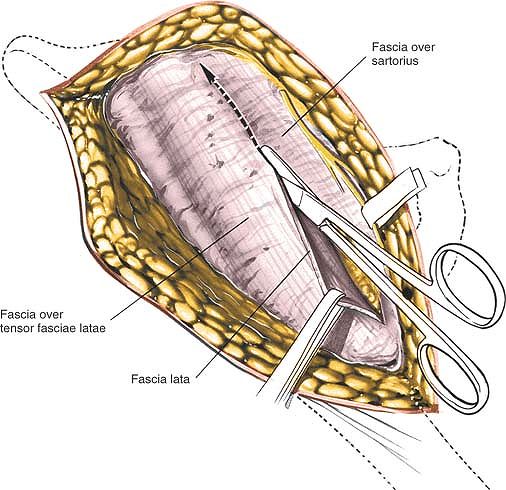

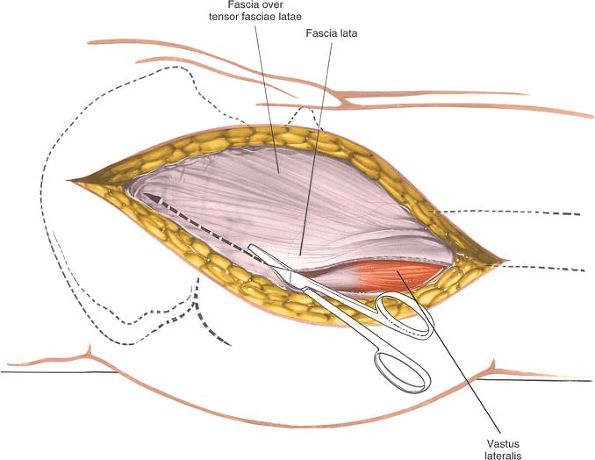

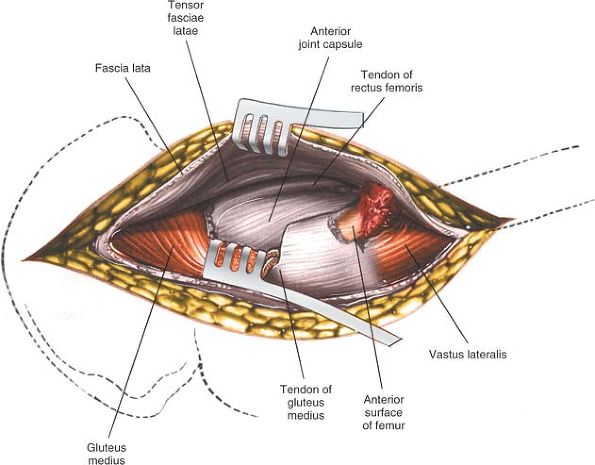

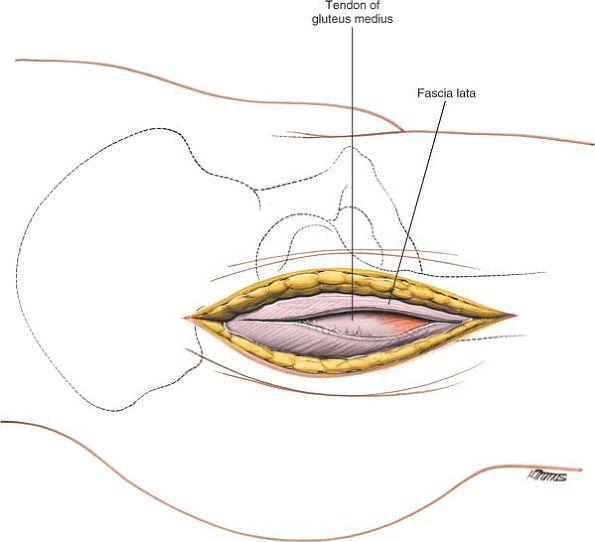

the deep fascia of the thigh. Using a sponge, gently push back

subcutaneous fat off the fascia lata until you can reach the fascia at

the posterior margin of the greater trochanter. Incise the fascia lata

at this point, entering the bursa that underlies it (Fig. 8-22). Now, divide the fascia lata in the line of its fibers superiorly, heading

proximally and anteriorly in the direction of the anterior superior

iliac spine. Finally, complete the fascial incision by extending the

cut distally and slightly anteriorly to expose the underlying vastus

lateralis muscle. Elevate this flap anteriorly by getting your

assistant to retract it forward, using a tissue-holding forcep. Now,

detach the few fibers of gluteus medius that arise from the deep

surface of this fascial flap and locate the interval between the tensor

fasciae latae (which is being lifted anteriorly by the assistant) and

the gluteus medius. This is best done by blunt dissection using your

fingers. A series of vessels cross the interval between the tensor

fasciae latae and the gluteus medius. These act as a guide to the

interval, but require ligation (Fig. 8-23).

|

|

Figure 8-22 Incise the fascia lata posterior to the tensor fasciae latae.

|

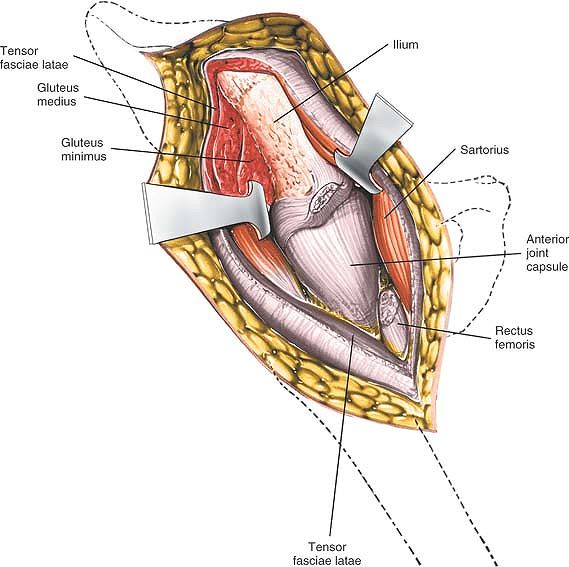

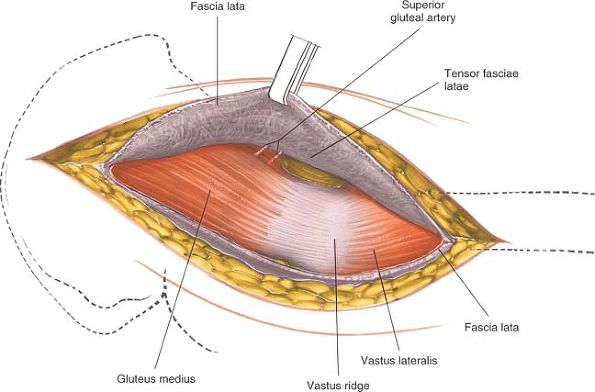

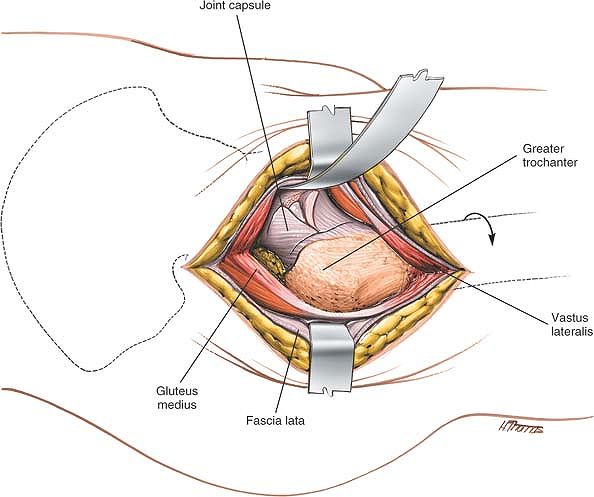

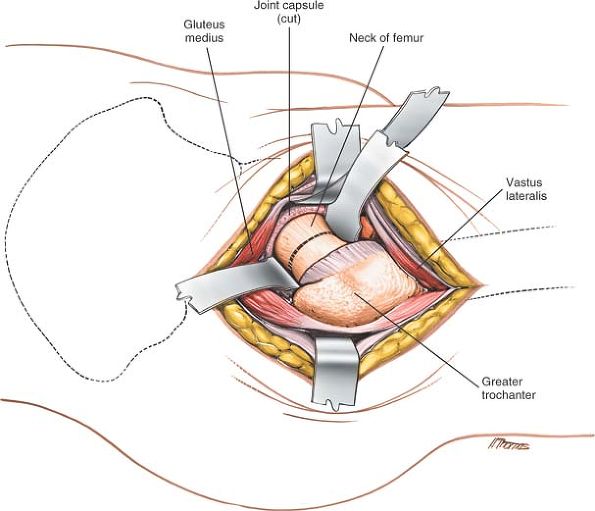

medius and minimus, and retract these muscles proximally and laterally

away from the superior margin of the joint capsule that covers the

femoral neck (Fig. 8-24).

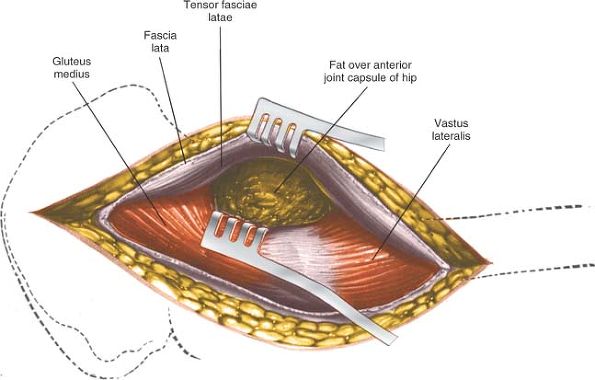

stretch. Identify the origin of the vastus lateralis at the vastus

lateralis ridge. Incise the origin using a cautery knife, and reflect

the muscle inferiorly for about 1 cm. Under it is the anterior aspect

of the joint capsule, at the junction of the femoral neck and shaft.

Bluntly dissect up the anterior part of the joint capsule, lifting off

the fat pad that covers it. The fat pad can reduce postoperative

scarring and adhesions and should be preserved even though it intrudes

into the operative field (Fig. 8-25).

all of the abductor mechanism and then dissecting up the femoral neck

superficial to the capsule of the joint until a suitable retractor can

be placed over the anterior lip of the acetabulum.

neutralizing the abductor mechanism, allowing the femur to fall

posteriorly. They also permit adduction of the leg for safe femoral

reaming and accurate positioning of prosthetic stems within the femoral

shaft. The technique chosen depends on the prosthesis to be used.

|

|

Figure 8-23

Retract the fascia lata and the tensor fasciae latae muscle, which it envelopes, anteriorly, revealing the gluteus medius and a series of vessels that cross the interval between the tensor fasciae latae and the gluteus medius. |

|

|

Figure 8-24

Retract the gluteus medius posteriorly and the tensor fasciae latae anteriorly, uncovering the fatty layer directly over the joint capsule. |

|

|

Figure 8-25 Bluntly dissect the fat pad off the anterior portion of the joint capsule to expose it and the rectus femoris tendon.

|

-

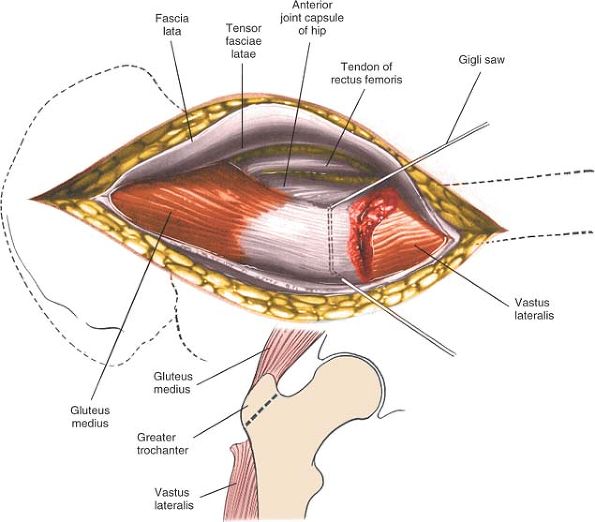

Trochanteric osteotomy.

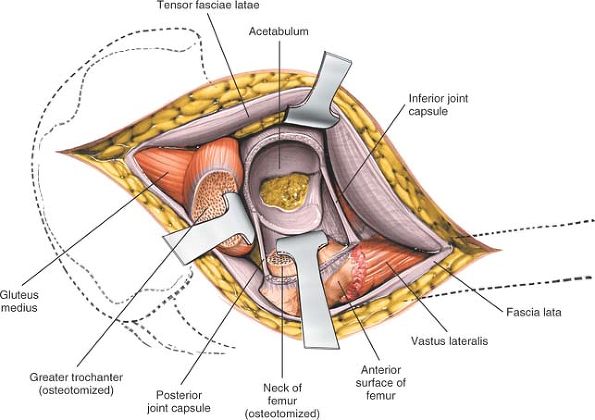

Performing a trochanteric osteotomy allows complete mobilization of the

gluteus medius and minimus muscles, which in turn allows excellent

exposure of the shaft of the femur during femoral reaming. Palpate the

vastus lateralis ridge on the lateral border of the femur, from distal

to proximal. Osteotomize the trochanter, using either an oscillating

saw or a Gigli saw, and reflect it upward with the attached gluteus

medius and minimus muscles. The base of the osteotomy should be at the

base of the vastus lateralis ridge. The upper end of the osteotomy may

be either intracapsular or extracapsular; the thickness of the

osteotomized portion of bone varies considerably, depending on the

prosthesis you intend to use. Alternatively, detach the trochanter

using two cuts at right angles to one another. This will leave the

trochanter looking like the roof of a Swiss chalet. This technique

maximizes the bone-to-bone contact surface area and, because of its

shape, also is inherently more stable after fixation than a straight

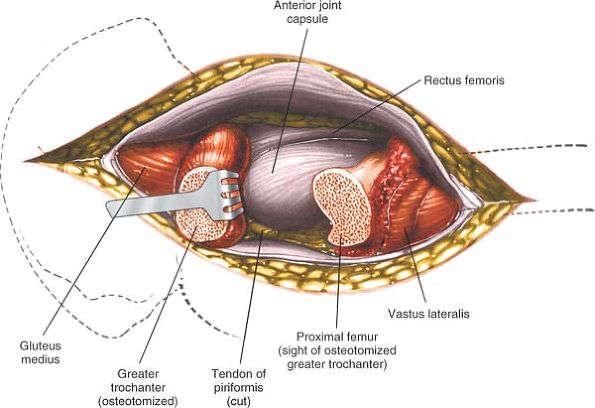

osteotomy.Reflect the osteotomized trochanter upward. To free it

completely, release some soft tissues (including the tendon of the

piriformis muscle) from its posterior aspect (Figs. 8-26 and 8-27). -

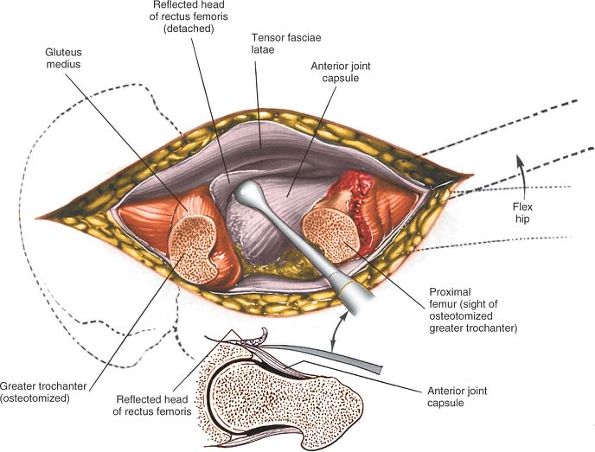

Partial detachment of the abductor mechanism.

Place a stay suture in the anterior portion of the gluteus medius just

above its insertion into the greater trochanter. Cut the insertion of

this anterior portion off the trochanter. Identify the thick white

tendon of the gluteus minimus as it inserts onto the anterior aspect of

the trochanter and incise it. The exact amount of the gluteus medius

that must be detached varies considerably from case to case (Fig. 8-28). In thin, nonmuscular people, you may even be able to preserve the whole of the gluteus medius attachment.

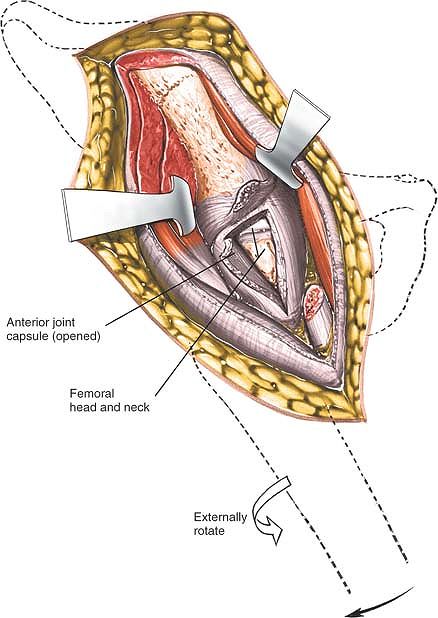

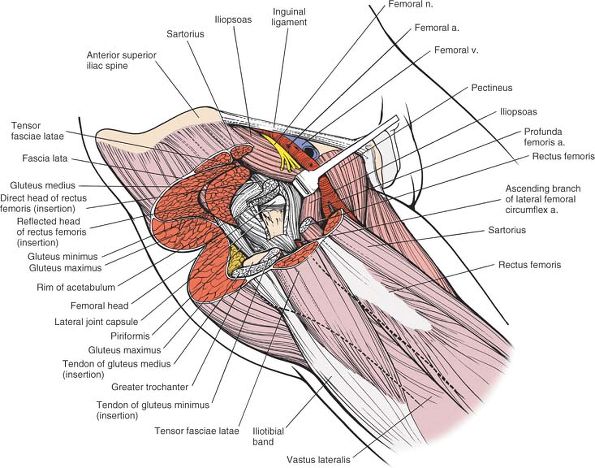

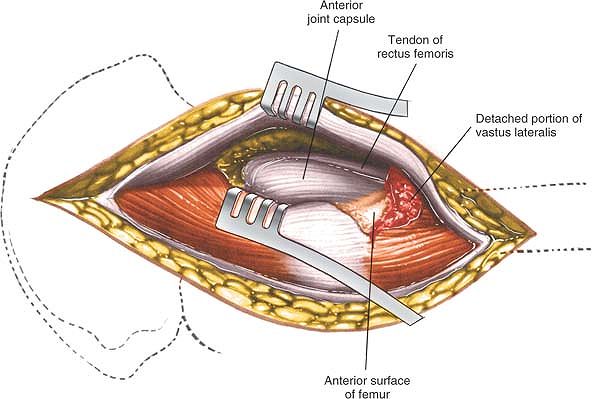

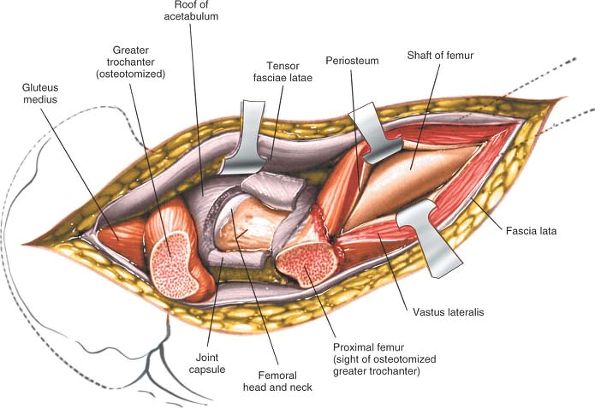

capsule in line with the femoral neck and head. Detach the reflected

head of the rectus femoris from the joint capsule to expose the

anterior rim of the acetabulum (Fig. 8-29, and inset).

(This plane is easier to open up if the leg is partly flexed, since the

rectus femoris remains relaxed. Flexing the leg also keeps the femoral

nerves and vessels off the stretch and farther from the operative

field.) Elevate part of the psoas tendon from the capsule. Because both

the rectus femoris and the psoas may insert into the capsule, the plane

between muscle and capsule is often difficult to establish.

acetabulum. Make certain that the dissection and the insertion of

retractors remain beneath the rectus femoris and iliopsoas, because the

neurovascular bundle lies anterior to the psoas. If you cannot develop

a plane between the psoas and the capsule, incise the capsule and

insert a retractor around the femoral head so that you can see the

joint better.

|

|

Figure 8-26 Osteotomize the greater trochanter.

|

|

|

Figure 8-27 Reflect the osteotomized portion of the trochanter superiorly (with the attached gluteus medius) to reveal the joint capsule.

|

|

|

Figure 8-28

The joint capsule may also be exposed by partial resection of the gluteus medius tendon from the anterior portion of the trochanter. |

|

|

Figure 8-29 Reflect the head of the rectus femoris from the anterior portion of the joint capsule.

|

|

|

Figure 8-30

Incise the anterior joint capsule to reveal the femoral head and neck and the acetabular rim. If further proximal exposure is needed, incise the fascia lata proximally toward the iliac crest and along the iliac crest anteriorly. To facilitate dislocation of the hip, incise the tight fascia lata and the fibers of the gluteus maximus (inset). |

longitudinal incision. Develop this into a T-shaped incision by cutting

the attachment of the capsule to the acetabulum as far around as you

can reach. Now incise the capsule transversely at the base of the neck

to convert the T-shaped incision into an H-shaped one (Fig. 8-30, and inset). Dislocate the hip by externally rotating it after you have performed an adequate capsulotomy (Fig. 8-31).

most laterally placed structure in the neurovascular bundle in the

femoral triangle, thus the structure closest to the operative field and

most at risk. The most common problem is compression neurapraxia,

caused by overexuberant medial retraction of the anterior covering

structures of the hip joint. Less frequently, the nerve is directly

injured by retractors placed in the substance of the iliopsoas (see Figs. 8-41 and 8-42).

may be damaged by incorrectly placed acetabular retractors that

penetrate the iliopsoas, piercing the vessels as they lie on the

surface of the muscle. You can avoid this complication by making sure

that the tip of the retractor is placed firmly on bone, with no

intervening tissue. The anterior retractor should be placed in the

1-o’clock position for the right hip and in the 11-o’clock position for

the left hip. Finding the correct plane between the rectus femoris and

the anterior part of the hip joint capsule is easier if the limb is in

about 30° of flexion.

|

|

Figure 8-31

To expose the acetabulum, dislocate and resect the femoral head. Placing three or four Homan-type retractors around the lip of the acetabulum provides excellent exposure. |

are being dislocated. For that reason, it is critical that you do an

adequate capsular release before attempting dislocation. To dislocate

the joint, lever the femoral head out of the acetabulum with a skid

(such as a Watson-Jones) while your assistant gently externally rotates

the limb. Your assistant has a considerable lever arm during this

procedure—if rotating the leg too forcibly, a spiral fracture of the

femur can result.

osteotomize the rim of the acetabulum, which often has an osteophyte,

to achieve dislocation.

extreme force, it is safer to perform a double osteotomy of the femoral

neck, excising a 1-cm portion of it: then remove the femoral head

(which is lying free) with a corkscrew.

limb is placed in full adduction and external rotation for reaming of

this femoral shaft. In order for the operator to gain a good enough

view of the cut surface of the femur, the femoral shaft must be

adducted. If the incision in the fascia lata has been placed too far

anteriorly, then the fascia lata will resist adduction and enthusiastic

assistants may cause femoral shaft fracture. This is the reason why the

fascia lata should be incised initially at the posterior border of the

greater trochanter. If the fascia lata gets in your way when attempting

to adduct the leg, it is safest to incise it along the lines of fibers

of gluteus maximus (see Fig. 8-30).

your superficial dissection, may prevent the adduction of the leg and

complete dislocation of the hip needed for femoral reaming because it

impinges on the trochanter. If it does, make an incision into the

posterior flap of the tensor fasciae latae, heading obliquely upward

and backward in line with the fibers of the gluteus maximus, which also

inserts into the iliotibial tract (see Fig. 8-30).

This maneuver may also be necessary to achieve reduction of the

prosthetic hip when the leg has been lengthened by the operative

procedure.

fascia on the muscle’s anterior aspect close to its origin from the ilium (see Fig. 8-30).

Alternatively, continue the fascial incision farther down the lateral

aspect of the femoral shaft. These maneuvers are seldom necessary.

|

|

Figure 8-32

Extend the incision down the lateral aspect of the thigh, incising the deep fascia and splitting the vastus lateralis in line with its musculature to reach the lateral aspect of the femur. |

correctly placing the retractors. Different approaches use different

retractors, but three or four Homan-type retractors placed around the

lip of the acetabulum, directly on bone, give as good an exposure as

any (see Fig. 8-31).

thigh, and incise the deep fascia in line with the skin incision. Split

the vastus lateralis to gain access to the lateral aspect of the femur.

In this way, you can usefully extend the approach to include the entire

length of the femur. Distal extension is often needed when the approach

is used for open reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the

femoral neck (Fig. 8-32).

allows excellent exposure of the hip joint for joint replacement. It

avoids the need for trochanteric osteotomy. Because the bulk of the

gluteus medius muscle is preserved intact, it permits early

mobilization of the patient following surgery. However, the approach

does not give as wide an exposure as the anterolateral approach with

trochanteric osteotomy. It is, therefore, difficult to perform revision

surgery using this approach.

|

|

Figure 8-33 Make a longitudinal incision centered over the tip of the greater trochanter in the line of the femoral shaft.

|

greater trochanter at the edge of the table. This allows the buttock

muscles and gluteal fat to fall posteriorly away from the operative

plane (see Fig. 8-20).

below. Palpate the lateral aspect of the greater trochanter and, below

that, the line of the femur that feels like a resistance against the

examining hand.

trochanter. Make a longitudinal incision that passes over the center of

the tip of the greater trochanter and extends down the line of the

shaft of the femur for approximately 8 cm (Fig. 8-33).

gluteus medius muscle are split in their own line distal to the point

where the superior gluteal nerve supplies the muscle. The vastus

lateralis muscle is also split in its own line lateral to the point

where it is supplied by the femoral nerve.

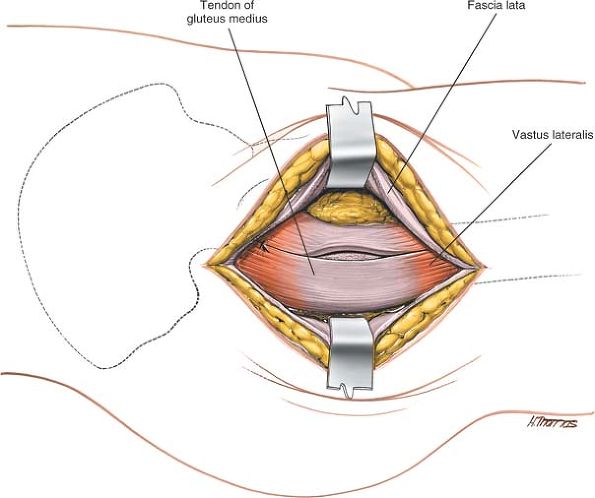

the skin incision. Retract the cut edges of the fascia to pull the

tensor fasciae latae anteriorly and the gluteus maximus posteriorly.

Detach any fibers of the gluteus medius that attach to the deep surface

of this fascia by sharp dissection. The vastus lateralis and the

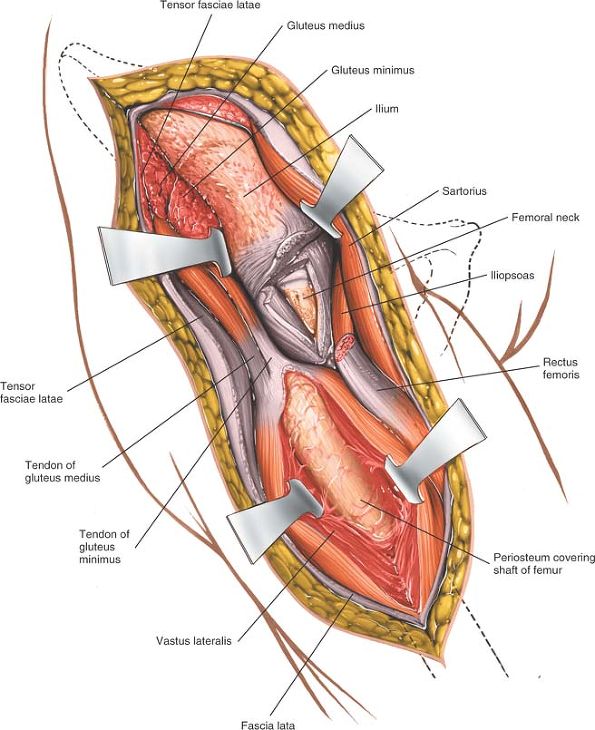

gluteus medius are now exposed (Fig. 8-34).

the trochanter. Do not go more than 3 cm above the upper border of the

trochanter because more proximal dissection may damage branches of the

superior gluteal nerve. Split the fibers of the vastus lateralis muscle

overlying the lateral aspect of the base of the greater trochanter.

Next, develop an anterior flap that consists of the anterior part of

the gluteus medius muscle with its underlying gluteus minimus and the

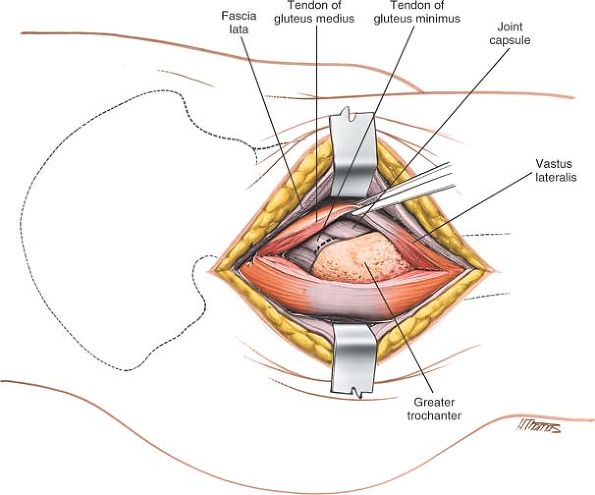

anterior part of the vastus lateralis muscle (Fig. 8-35).

You will need to detach the muscles from the greater trochanter either

by sharp dissection or by lifting off a small flake of bone. Continue

developing this anterior flap, following the contour of the bone onto

the femoral neck, until the anterior hip joint capsule is fully

exposed. You will need to detach the insertion of the gluteus minimus

tendon to the anterior part of the greater trochanter (Fig. 8-36).

Develop the plane between the hip joint capsule and the overlying

muscles, using a swab pushed into the potential space using a blunt

instrument.

|

|

Figure 8-34 Divide the deep fascia in the line of the skin incision, retracting the fascial edges to pull the tensofasciolate anteriorly.

|

|

|

Figure 8-35

Split the fibers of gluteus medius above the tip of the greater trochanter and extend this incision distally on the lateral aspect of the trochanter until 2 cm of the vastus lateralis is also split. |

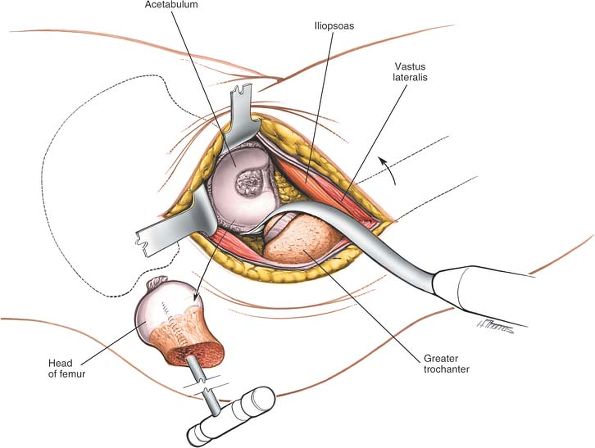

Extract the femoral head using a cork screw. Complete the exposure of

the acetabulum by inserting appropriate retractors around the

acetabulum (Fig. 8-39).

runs between the gluteus medius and minimus muscles approximately 3 to

5 cm above the upper border of the greater trochanter. More proximal

dissection may cut this nerve or may produce a traction injury. For

this reason, insert a stay

suture

at the apex of the gluteus medius split. This will ensure that the

split does not inadvertently extend itself during the operation (see Fig. 8-37).

|

|

Figure 8-36

Develop this anterior flap and divide the tendon of the gluteus minimus muscle to reveal the anterior aspect of the hip joint capsule. |

|

|

Figure 8-37 Enter the capsule using a longitudinal T-shaped incision.

|

|

|

Figure 8-38 Osteotomize the femoral neck using an oscillating saw.

|

lateral structure in the anterior neurovascular bundle of the thigh, is

vulnerable to inappropriately placed retractors. Anterior retractors

should be placed strictly on the bone of the anterior aspect of the

acetabulum and should not infringe on the substance of the psoas muscle.

the shaft of the femur, split the vastus lateralis muscle in the

direction of its fibers (see Lateral Approach in Chapter 9). The incision cannot be extended proximally.

|

|

Figure 8-39 Extract the femoral head. Insert appropriate retractors to reveal the acetabulum.

|

|

|

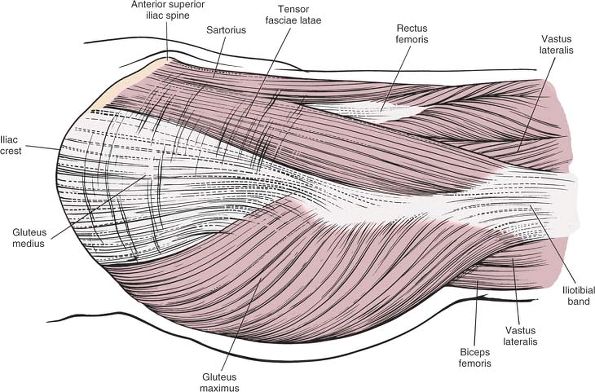

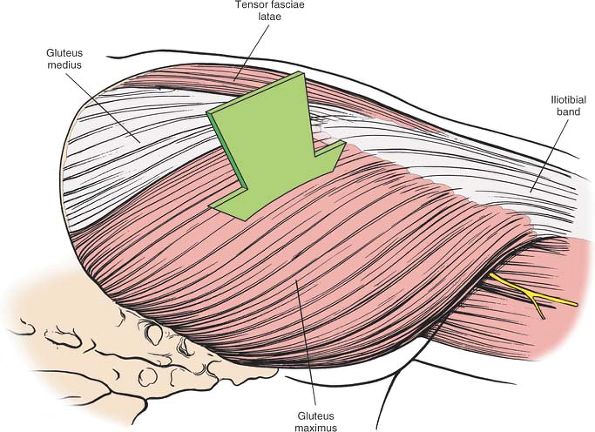

Figure 8-40 Superficial musculature of the lateral aspect of the hip.

|

muscles around the hip joint. In hip surgery, its importance lies in

its relationship to three muscles: the sartorius, the tensor fasciae

latae, and the gluteus maximus. The fascia lata covers the sartorius;

it also splits into a deep and superficial layer to enclose the tensor

fasciae latae and gluteus maximus (Fig. 8-40).

If the iliac crest is viewed from the lateral side, the outer layer of

the covering seems to consist of the fascia lata of the thigh and the

muscles that it encloses. The sartorius lies farther anteriorly. The

gluteus medius, which arises from the outer wing of the ilium, is

covered by the fascia lata, not enclosed by it (Fig. 8-41).

to the hip lies in the relationship between the tensor fasciae latae

and the gluteus medius. The tensor fasciae latae, a superficial

structure, arises from the anterior portion of the outer lip of the

iliac crest. The gluteus medius arises from the outer wall of the

ilium, between the anterior and posterior gluteal lines. The origins of

the two muscles are, therefore, almost continuous, but the tensor

fasciae latae is slightly more superficial (lateral) and anterior than

the gluteus medius (Fig. 8-42).

tract, the thickening of the deep fascia of the thigh, while the

gluteus medius inserts into the anterior and lateral part of the

greater trochanter. Thus, as the muscles run from origins to

insertions, the tensor fasciae latae rises to an even more superficial

position in relation to the gluteus medius (see Figs. 8-41 and 8-42).

lata posterior to the posterior margin of the tensor fasciae latae and

retract the cut fascial edge anteriorly. Because the fascia lata

actually encloses the tensor fasciae latae, the muscle is retracted

with the fascia (see Fig. 8-41).

|

|

Figure 8-41

Resecting the sartorius, tensor fasciae latae, and fascia lata and reflecting the anterior portion of the gluteus maximus posteriorly reveal the gluteus medius and more anterior structures of the hip region. The fascia lata splits to envelop the tensor fasciae latae, but it only covers the gluteus medius muscle. Gluteus Medius. Origin. Outer aspect of ilium between anterior and posterior gluteal lines and its overlying fascia. Insertion. Lateral surface of greater trochanter. Action. Abductor and medial rotator of hip. Nerve supply. Superior gluteal nerve.

|

plane to reach the femoral neck; then they follow the joint capsule

medially to expose the anterior rim of the acetabulum. The techniques

used in this approach differ mainly in how they detach the abductor

mechanism to allow adduction of the femur for femoral reaming and

retraction of the femoral neck posteriorly for adequate exposure of the

acetabulum.

The interval between them forms a true internervous plane. Two

structures, the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and the ascending

branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery, lie between them; they

must be identified and avoided during the dissection (see Figs. 8-14 and 8-15).

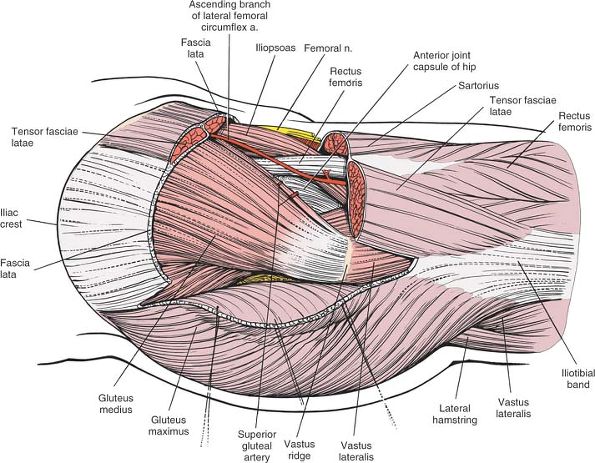

consists of the rectus femoris (femoral nerve) and the gluteus medius

(superior gluteal nerve). The interval between them is also an

internervous plane; exploiting it is difficult, mainly because the

short head of the rectus femoris originates partly from the anterior

capsule of the hip joint, where the iliopsoas partly inserts (see Figs. 8-15 and 8-16).

|

|

Figure 8-42

The gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and rectus femoris have been resected to reveal the muscular layers down to the hip joint capsule. Resection of the joint capsule exposes the acetabulum and the femoral head and neck. |

vastus lateralis and gluteus medius to provide direct access to the hip

joint capsule. The approach is limited superiorly by the superior

gluteal nerve, which traverses the substance of gluteus medius.

is the site of attachment of two important structures. The sartorius

takes its origin from it, and the inguinal ligament uses it as a

lateral attachment. The anterior superior iliac spine is rarely used as

a bone graft because the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh lies so

close to it.

-

The external oblique

forms the outer layer of the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall. It

originates from the outer strip of the anterior half of the iliac crest. -

The internal oblique

forms the middle layer of the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall.

It originates from the center strip of the anterior half of the iliac

crest. -

The tensor fasciae latae arises from the outer lip of the anterior half of the iliac crest.

are not detached during the anterior approach; the tensor fasciae latae

is.

results partly from the pull of the aponeurosis of the vastus lateralis

during growth and partly from the fusion of the trochanter apophyses of

the shaft of the femur (Fig. 8-43; see Fig. 8-41).

side from an almost continuous line of origin along the anterior end of

the iliac crest. The two muscles diverge a short distance below the

anterior superior iliac spine so that the rectus femoris can emerge

from between them (see Fig. 8-14).

itself is triangular. In cross section, it is unusually slim at its

origin and thick just before it inserts into the iliotibial tract. Its

action is difficult to interpret, because another large muscle, the

gluteus maximus, also inserts into the iliotibial tract. In cases of

poliomyelitis, dividing the iliotibial tract relieves flexion and

abduction contractures of the hip joint.

important in standing in a one-legged stance, waiting in a bus line,

for instance, where the muscle may maintain the stability of the

extended knee and hip.12

considerably finer than those of the gluteus medius, but the difference

in the quality of fibers rarely makes it easier to identify the plane

between the two muscles.

muscle in the body, crossing both the hip and the knee. The individual

fibers within the muscle are also the longest in the body; they leave

the sartorius weak but capable of extraordinary contraction.

fasciae latae and the sartorius. Both complicate the superficial

surgical dissection of the anterior approach.

-

The ascending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery

is a comparatively large artery that often requires ligation. It is one

of a series of vessels that run circumferentially around the thigh (see

Anterior Approach to the Hip above). This is one of the rare instances in which a vessel crosses an internervous plane (see Figs. 8-15 and 8-16). -

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh)

arises from the lumbar plexus or, occasionally, from the femoral nerve

itself. From there, it descends through the pelvis on the surface of

the iliacus muscle. It enters the thigh under the inguinal ligament

anywhere between the anterior superior iliac spine and the mid-inguinal

point. The nerve pierces the fascia lata just below and medial to

P.441

the

anterior superior iliac spine. The path it takes may vary considerably,

as it can pass either around or through the sartorius muscle (see Fig. 8-14).

|

|

Figure 8-44 The anterior and anterolateral approaches to the hip joint, showing their muscular boundaries.

|

lateral femoral cutaneous nerve have been reported, particularly from

the section that runs behind the inguinal ligament and from the point

where the nerve pierces the fascia lata. These syndromes consist of

painful paresthesias on the lateral side of the thigh, conditions that

may be relieved by decompressing the nerve. Occasionally, decompression

may have to extend into the pelvis, since the nerve may be compressed

on the surface of the iliacus.

runs through both the superficial and the deep surgical dissection,

mainly because its origin is relatively superficial while its insertion

is deep (see Figs. 8-40, 8-41 and 8-42).

From an anterior approach, the gluteus medius appears to be one of the

muscles of the inner layer over the hip joint. From an anterolateral

approach, it occupies a more superficial position.

this muscle, knowledge of which prevents confusion during the

anterolateral approach to the hip. First, fibers of the gluteus medius

commonly arise from the deep surface of the fascia latae. This means

that when you elevate the fascial flap to gain access to the anterior

border of gluteus medius, you often have to detach muscular fibers from

the inner surface of the fascia. Although the fascia lata encloses the

tensor fasciae latae muscle and covers the gluteus medius, in many

cases the fascia lata actually serves as part of the origin of the

gluteus medius muscle.

Second,

there is often a thin fascial layer covering the gluteus medius muscle

on its outer aspect just above the greater trochanter. In order to pick

up the anterior border of the muscle for dissection, you frequently

need to incise this fascial layer. If you do not do this, it is

difficult to pick up the anterior border of the muscle since this

fascial layer is continuous with the fascia covering the outer aspect

of the greater trochanter.

Paralysis leads to a Trendelenburg gait, in which the patient cannot

prevent his hip from adducting when he puts weight on the affected leg

during walking.

muscle and the anterior part of the greater trochanter. It may become

inflamed, producing pain.

crosses the intermuscular plane between the gluteus medius and the

tensor fasciae latae and must be cut if the dissection extends up to

the pelvis. Whether denervation of the tensor fasciae latae muscle is

clinically significant is a moot point.

and vastus lateralis. The anterior flap of the dissection is lifted off

the underlying greater trochanter until the tendon of gluteus minimus

and the anterior hip joint capsule are revealed. The exposure is made

possible because it utilizes the bursa beneath gluteus medius that

separates the muscle from the bone superiorally (see above).

finding the plane between the joint capsule and the surrounding

structures, because every muscle that crosses the hip joint directly

sends some of its fibers to insert into the capsule.

and the gluteus medius. The rectus femoris has two heads of origin,

both of which must be detached. The straight head arises from the

anterior inferior iliac spine; the reflected head arises from just

above the acetabulum and from the joint capsule itself. The gluteus

medius arises from the outer aspect of the ilium, between the middle

and posterior gluteal lines. While the intermuscular plane between the

two muscles is easy to define and develop, the rectus is difficult to

mobilize from the anterior joint capsule because part of it actually

originates from the capsule itself (see Figs. 8-15, 8-16 and 8-17).

intrudes into the inferomedial portion of the operative field, must be

retracted medially to expose the anterior part of the joint. The

iliopsoas crosses the hip joint directly; it sends some of its fibers

to insert into the joint capsule (see Fig. 8-17).

muscles, the psoas major and the iliacus. The iliopectineal bursa

separates part of the tendon from the hip joint. The bursa, which may

communicate with the joint itself, is usually obliterated in

degenerative disease of the hip, leaving the tendon anchored to the

anterior and medial portions of the joint capsule.

the thigh beneath the inguinal ligament. They lie on the psoas major

muscle, halfway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic

tubercle, the midinguinal point. The femoral artery is thus directly

anterior to the hip joint, with the psoas muscle interposed. The

femoral nerve lies lateral, and the femoral vein medial, to the artery.

(This arrangement can be remembered through the mnemonic “VAN”—vein, artery, nerve.)

of the acetabulum do not damage any of these structures, although a

neurapraxia of the femoral nerve (the most lateral of the triad) may

occur if retraction is prolonged and forceful.

bones are probably biting into the substance of the psoas; they can

damage any of the neurovascular structures that lie in the femoral

triangle. Avoiding these complications depends on keeping to the bone

of the acetabular margin and staying beneath the reflected head of the

rectus femoris and the iliopsoas.

division of gluteus minimus tendon. This does not appear to cause a

postoperative Trendelenburg gait, however.

capsule and the overlying muscles. This plane is occupied by a small

amount of fatty tissue that allows the plane to be opened up by using a

swab and blunt dissection. This useful plane is always present in

primary surgery, but in revision surgery, it is obliterated by scar

tissue. Therefore, there is inherently more risk of damaging the

femoral vessels that lie anterior to the hip joint capsule in revision

surgery than in primary surgery.

access to the joint and can be performed with only one assistant.

Because they do not interfere with the abductor mechanism of the hip,

they avoid the loss of abductor power in the immediate postoperative

period. Posterior approaches allow excellent visualization of the

femoral shaft, thus are popular for revision joint replacement surgery

in cases in which the femoral component needs to be replaced.

posterior capsule, if dislocation of any prosthesis occurs, it will

result from flexion and internal rotation of the hip. Thus, there may

be a higher dislocation rate than that from anterior approaches if the

posterior approach is used in fractured neck of femur surgery in

elderly bedridden patients who often lie in bed with their hips in a

flexed and adducted position.

-

Hemiarthroplasty14,15,16

-

Total hip replacement, including revision surgery

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of posterior acetabular fractures

-

Dependent drainage of hip sepsis

-

Removal of loose bodies from the hip joint

-

Pedicle bone grafting17

-

Open reduction of posterior hip dislocations

|

|

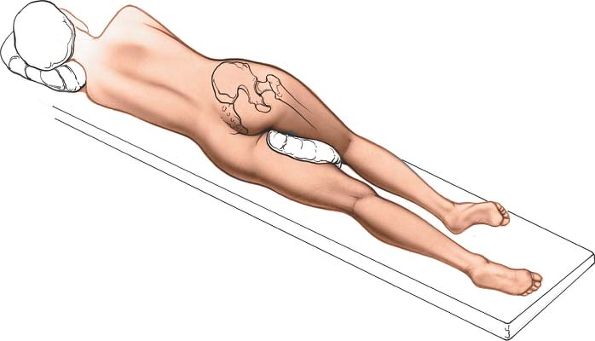

Figure 8-45 Position of the patient on the operating table for the posterior approach to the hip joint.

|

affected limb uppermost. Because most patients requiring surgery are

elderly and have delicate skin, it is important to protect the bony

prominences of the legs and pelvis with pads placed under the lateral

malleolus and knee of the bottom leg and a pillow between the knees.

Drape the limb free to leave room for movement during the procedure (Fig. 8-45).

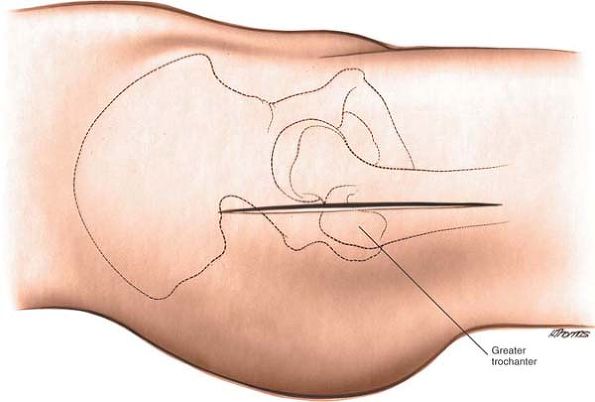

on the outer aspect of the thigh. The posterior edge of the trochanter

is more superficial than the anterior and lateral portions, and, as

such, it is easier to palpate (see Fig. 8-21).

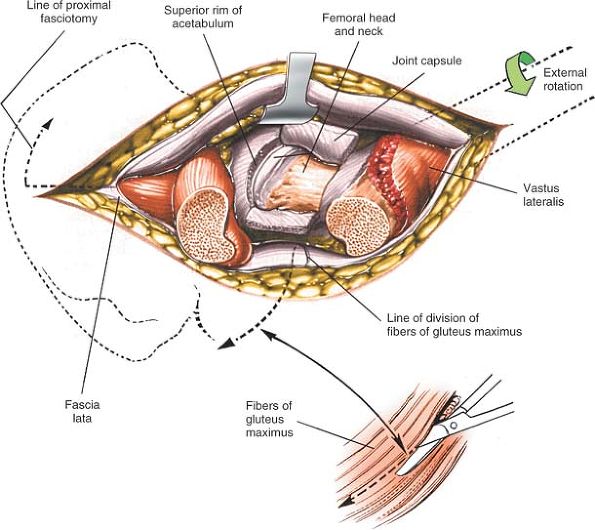

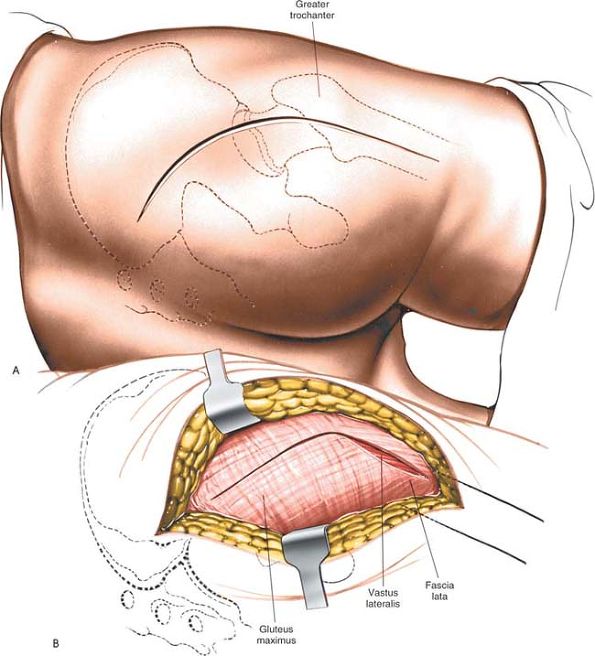

posterior aspect of the greater trochanter. Begin your incision some 6

cm to 8 cm above and posterior to the posterior aspect of the greater

trochanter. The part of the incision that runs from this point to the

posterior aspect of the trochanter is in line with the fibers of the

gluteus maximus. Curve the incision across the buttock, cutting over

the posterior aspect of the trochanter, and continue down along the

shaft of the femur (Fig. 8-47A).

If you flex the hip 90° and make a straight longitudinal incision over

the posterior aspect of the trochanter, it will curve into a

“Moore-style” incision when the limb is straight. The final incision is

curved and 10 to 15 cm long, centered on the posterior aspect of the

greater trochanter.

However, the gluteus maximus, which is split in the line of its fibers,

is not significantly denervated because it receives its nerve supply

well medial to the split (Fig. 8-46).

|

|

Figure 8-46

There is no true internervous plane. Split the fibers of the gluteus maximus, a procedure that does not cause significant denervation of the muscle. |

femur to uncover the vastus lateralis. Lengthen the fascial incision

superiorly in line with the skin incision, and split the fibers of the

gluteus maximus by blunt dissection (Fig. 8-47B). (The fascial covering of the gluteus maximus varies considerably in its thickness. In the elderly, it is quite thin.)

superior and inferior gluteal arteries, which enter the deep surface of

the muscle and ramify outward like the spokes of a bicycle wheel;

hence, splitting the muscle inevitably crosses a vascular plane. In

addition to the arterial bleeding, venous bleeding must be anticipated.

If you split the muscle gently, you may be able to pick up, coagulate,

and cut the crossing vessels before they are stretched and avulsed by

the blunt dissection of the split. Obviously, vessels

that are torn when stretched retract into the muscle and are more difficult to control.

|

|

Figure 8-47 (A) Skin incision for the posterior approach to the hip joint. (B) Incise the fascia lata.

|

|

|

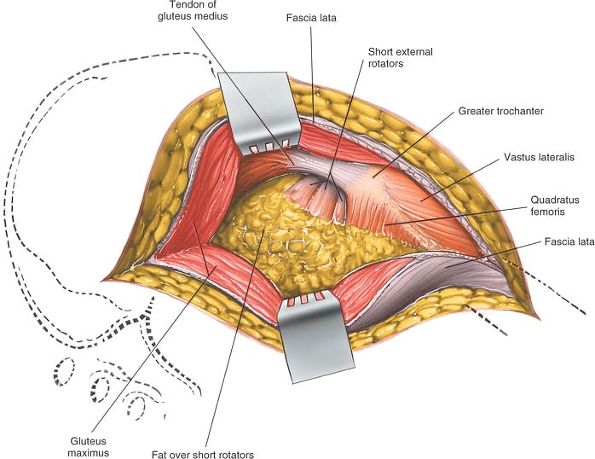

Figure 8-48 Retract the gluteus maximus to reveal the fatty layer over the short external rotators of the hip.

|

deep fascia of the thigh. Underneath is the posterolateral aspect of

the hip joint, still covered by the short external rotator muscles,

which attach to the upper part of the posterolateral aspect of the

femur (Fig. 8-48).

through the greater sciatic notch and runs down the back of the thigh

on the short external rotator muscle, encased in fatty tissue. The

nerve crosses the obturator internus, the two gemelli, and the

quadratus femoris before disappearing beneath the femoral attachment of

the gluteus maximus. You can find the nerve lying on the short external

rotators, and it can be easily palpated. Do not dissect to see the

nerve; you may cause unnecessary bleeding from the vessels lying in the

fat around it (Fig. 8-49).

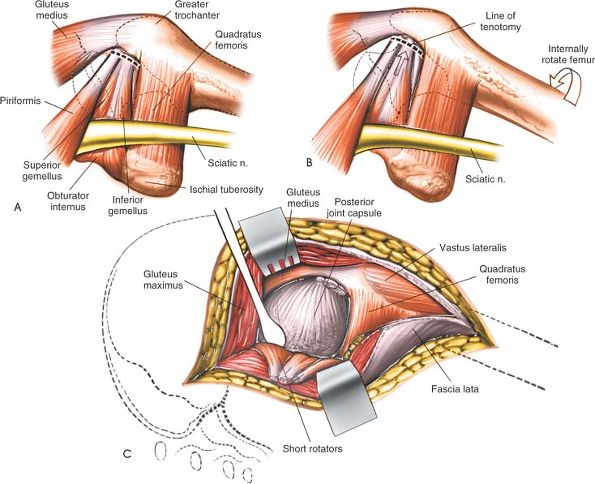

rotator muscles on a stretch (making them more prominent) and to pull

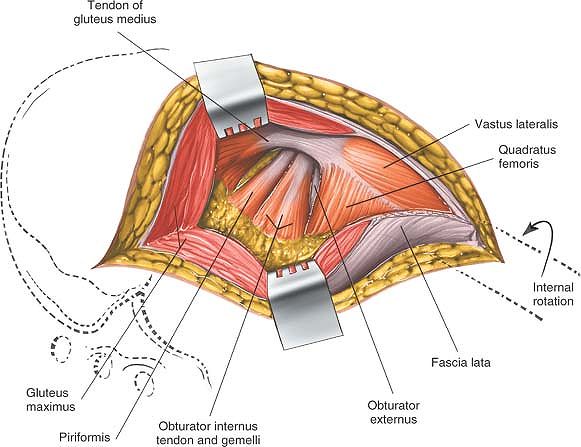

the operative field farther from the sciatic nerve (Fig. 8-50A,B).

internus tendons just before they insert into the greater trochanter.

Detach the muscles close to their femoral insertion and reflect them

backward, laying them over the sciatic nerve to protect it during the

rest of the procedure (Fig. 8-50C).

(The upper part of the quadratus femoris may also have to be divided to

fully expose the posterior aspect of the joint capsule, but the muscle

contains troublesome vessels that arise from the lateral circumflex

artery. Normally, it should be left alone.)

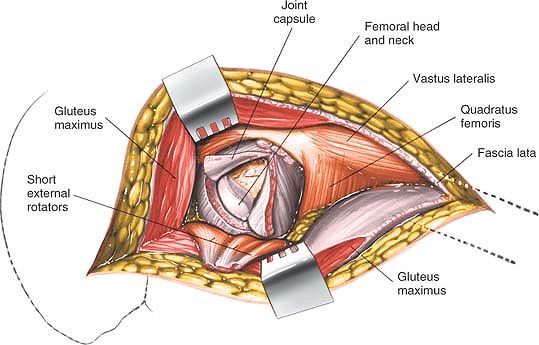

fully exposed. The hip joint capsule can be incised with a longitudinal

or T-shaped incision. Dislocation

of the hip is achieved by internal rotation after capsulotomy (Fig. 8-51). Posterior joint capsulotomy will have exposed the femoral head and neck.

|

|

Figure 8-49

Push the fat posteromedially to expose the insertions of the short rotators. Note that the sciatic nerve is not visible; it lies within the substance of the fatty tissue. Place your retractors within the substance of the gluteus maximus superficial to the fatty tissue. |

exposed or transected during this approach. However, it is sometimes

involved in major complications. It can be damaged if it is compressed

by the posterior blade of a self-retaining retractor used to split the

gluteus maximus. Always keep the retractors on the cut surfaces of the

rotators; the muscles will protect the nerve.

common peroneal branches within the pelvis; on occasion, you may expose

these two “sciatic nerves” during this approach. If you have identified

the sciatic nerve but think that it looks too small, search for the

nerve’s other branch; it is in danger if it is overlooked.

leaves the pelvis beneath the piriformis. It spreads cephalad to supply

the deep surface of the gluteus maximus. Its branches are inevitably

cut when the gluteus maximus is split; you can identify and coagulate

them before they are avulsed if you are dissecting carefully.

from beneath the lower border of the piriformis when pelvic fractures

involve the greater sciatic notch. If it retracts into the pelvis and

bleeding is brisk, turn the patient over into the supine position, open

the abdomen, and tie off the artery’s feeding vessel, the internal

iliac artery.

-

Enlarge the skin incision. Obese patients

may have a considerable layer of subcutaneous tissue over the buttock

that restricts deep exposure; lengthening the skin incision and

dissecting subcutaneously can compensate for this problem. -

Extend the fascial incision superiorly and inferiorly.

-

Detach the upper half of the quadratus femoris. Because the muscle contains troublesome vessels,

P.448P.449

it should be divided about 1 cm from its insertion to make hemostasis

easier. Its excellent blood supply is useful both when the muscle is

transposed and in treatment of some cases of nonunion of femoral neck

fractures (Fig. 8-52).![]() Figure 8-50 (A, B)

Figure 8-50 (A, B)

Internally rotate the femur to bring the insertion of the short

rotators of the hip as far lateral to the sciatic nerve as possible. (C)

Detach the short rotator muscles close to their femoral insertion and

reflect them backward, laying them over the sciatic nerve to protect it. Figure 8-51 Incise the posterior joint capsule to expose the femoral head and neck.

Figure 8-51 Incise the posterior joint capsule to expose the femoral head and neck. -

Detach the insertion of the gluteus

maximus tendon from the femur to increase the exposure of the femoral

neck and shaft. This maneuver is particularly useful during total joint

replacement, especially revision joint replacement. If you detach the

tendon, position acetabular retractors on the rim of the acetabulum as

you would in the anterolateral approach. As long as the retractors are

firmly on bone and do not crush soft tissues against the acetabular

rim, no vital structures will be damaged (see Fig. 8-52).

|

|

Figure 8-52 To gain additional exposure, cut the quadratus femoris and the tendinous insertion of the gluteus maximus.

|

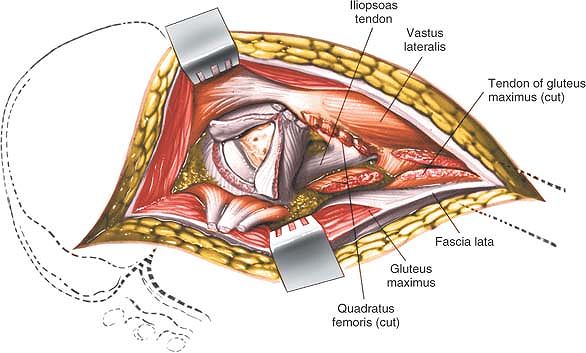

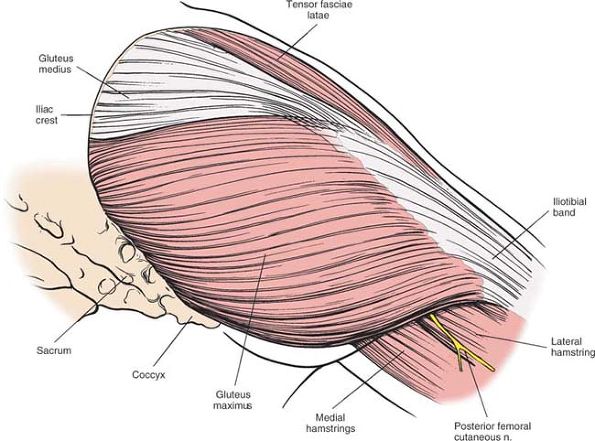

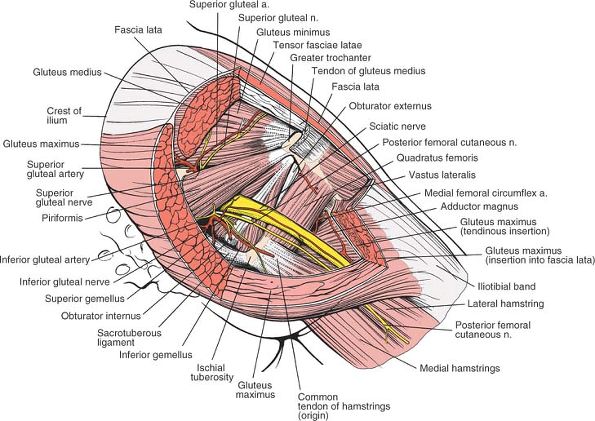

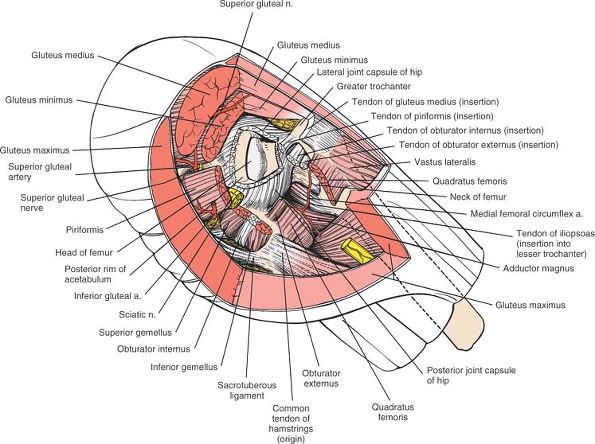

joint form two sheaths or layers. The outer layer consists of the

gluteus maximus. The inner layer consists of the short external

rotators of the hip, the piriformis, the superior gemellus, the

obturator internus, the inferior gemellus, and the quadratus femoris.

The sciatic nerve runs vertically between the two layers, down through

the operative field (Figs. 8-53 and 8-54).

buttock like the front cover of a book. It inserts partly into the

iliotibial band and partly into the gluteal tuberosity of the femur.

Also inserting into the band, but further anteriorly, is the tensor

fasciae latae. Together, the gluteus maximus, the fascia lata (which

covers the gluteus medius), and the tensor fasciae latae form a

continuous fibromuscular sheath, the outer layer of the hip musculature

(see Fig. 8-53). As Henry18 noted, the layer can be viewed as the “pelvic deltoid”: it covers the hip much as the deltoid muscle covers the shoulder.

|

|

Figure 8-53 The superficial musculature of the posterior approach of the hip joint. The gluteus maximus predominates.

Gluteus Maximus. Origin.

From posterior gluteal line of ilium and that portion of the bone immediately above and behind it; from posterior surface of lower part of sacrum and from side of coccyx; and from fascia covering gluteus medius. Insertion. Into iliotibial band of fascia lata and into gluteal tuberosity. Action. Extends and laterally rotates thigh. Nerve supply. Inferior gluteal nerve. |

each of which changes the posterior approach. The most natural

separation, the Marcy-Fletcher approach,19 lies at the anterior border of the

gluteus maximus, between the gluteus maximus (inferior gluteal nerve)

and the gluteus medius. This approach uses a true internervous plane.

|

|

Figure 8-54

The gluteus maximus and the gluteus medius have been resected to reveal the gluteus minimus, the piriformis, and the short rotator muscles. Note the relationship of the neurovascular structures to the piriformis. Gluteus Minimus. Origin. From outer surface of ilium between anterior and inferior gluteal lines. Insertion. Into impression on anterior border of greater trochanter via tendon that gives expansion to joint capsule. Action. Rotates thigh medially and abducts it. Nerve supply. Superior gluteal nerve.

Piriformis. Origin. From front of sacrum via fleshy digitations from second, third, and fourth portions of sacrum. Insertion. Into upper border of greater trochanter via round tendon. Action. Rotates thigh laterally and abducts it. Nerve supply. Branches from first and second sacral nerves.

Obturator Internus. Origin. From inner surface of anterolateral wall of pelvis and from surfaces of greater part of obturator foramen. Insertion. Onto medial surface of greater trochanter above trochanteric fossa. Action. Rotates thigh laterally. Nerve supply. Any nerve from sacral plexus.

Quadratus Femoris. Origin. From upper part of external border of tuberosity of ischium. Insertion. Into upper part of linea quadrata, the line that extends vertically downward from intertrochanteric crest. Action. Rotates thigh laterally. Nerve supply. Branch from sacral plexus.

|

|

|

Figure 8-55 The gluteus minimus, piriformis, and short rotators have been resected to uncover the posterior aspect of the hip joint.

|

involve splitting the fibers of the gluteus maximus. They are more

popular than the Marcy-Fletcher approach even though they do not

operate in an internervous plane, mainly because they offer excellent

exposure of the hip joint.

which the skin incision is centered, is the easiest bony prominence to

palpate around the hip. Its posterior aspect is relatively free of

muscles; its anterior and lateral aspects are covered by the tensor

fasciae latae and the gluteus medius and minimus muscles and are much

less accessible.

neck and the shaft of the femur. From there, it projects both upward

and backward (Fig. 8-56). The following five muscles insert into it:

-

The gluteus medius

attaches by a broad insertion into its lateral aspect. Below this

insertion, the bone is covered by the beginnings of the iliotibial

tract. A bursa, occasionally a site of inflammation, lies between the

tract and the bone over the relatively bare portion of the trochanter.

The bursa can be the site of bacterial infection (historically, most

frequently tuberculosis). -

The gluteus minimus is attached to the anterior aspect of the trochanter, where its tendon is divided in the anterolateral approach (see Fig. 8-54).

-

The piriformis

inserts via a tendon into the middle of the upper border of the greater

trochanter. Its insertion forms a surgical landmark for the insertion

of certain types of intramedullary rods into the femur. The bone is

perforated just medial to it,

P.453

the easiest route into the medulla of the femoral shaft (see Fig. 8-54).![]() Figure 8-56 Osteology of the posterior aspect of the hip and pelvis.

Figure 8-56 Osteology of the posterior aspect of the hip and pelvis. -

Obturator externus tendon.

Immediately below the insertion of the piriformis lies the trochanteric

fossa, a deep pit that marks the attachment of the obturator externus

tendon (see Fig. 8-54). -

The obturator internus tendon inserts with the two gemelli into the upper border of the trochanter, posterior to the insertion of the piriformis (see Fig. 8-54).

cleavage of the skin at almost 90°, but the resulting scar is always

hidden by clothing. Most patients who undergo this approach are elderly

and tend not to form exuberant scar tissue, and they heal with a fine

line scar.

outer muscle layer by splitting the fibers of the gluteus maximus, the

single largest muscle in the body. The fibers of the gluteus maximus

are extremely coarse; they run obliquely downward and laterally across

the buttock. The muscle’s innervation, the inferior gluteal nerve,

emerges from the pelvis beneath the inferior border of the piriformis

and almost immediately enters the muscle’s deep surface close to its

medial border, its origin. From there, the nerve’s branches spread

throughout the muscle. Splitting the gluteus maximus close to its

lateral insertion does not denervate significant portions of the

muscle, because its main nerve supply passes well medial to the most

medial point of splitting (see Fig. 8-53).

standing still; it comes into play during stair climbing or standing up

from a sitting position. (During normal walking, hip extension is

primarily a function of the hamstrings rather than the gluteus maximus.)

inner muscular layer (the short external rotators of the hip) to expose

the posterior hip joint capsule (see Fig. 8-55).

Five muscles form the inner layer: the piriformis, the superior

gemellus, the tendon of the obturator internus, the inferior gemellus,

and the quadratus femoris.

passing structures is the key to understanding the neurovascular

anatomy of the area (see Fig. 8-54). All

neurovascular structures that enter the buttock from the pelvis pass

through the greater sciatic notch, either superior or inferior to the

piriformis, which itself passes from the pelvis to the buttock through

the notch.

|

|

emerges from the pelvis above the piriformis. It crosses behind the

posterior border of the gluteus medius and runs in the space between

the gluteus medius and the gluteus minimus, supplying both before

sending fibers to the tensor fasciae latae.

the largest branch of the internal iliac artery, enters the pelvis

above the upper border of the piriformis and runs with its nerve,

supplying the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus and sending a nutrient

vessel to the ilium on the gluteal line. The nutrient vessel may bleed

when a larger posterior iliac bone graft is taken. The superior gluteal

artery also sends branches to the overlying gluteus maximus, forming

part of the muscle’s dual arterial supply.

fractures, especially in those involving the greater sciatic notch. If

it retracts into the pelvis, its bleeding must be controlled by an

extraperitoneal approach to the pelvis so that its feeding vessel, the

internal iliac artery, can be ligated. In pelvic fractures, selective

angiography may aid in the diagnosis of a ruptured superior gluteal

artery. During the angiography, the artery may be embolized through the

diagnostic cannula, avoiding a pelvic exploration.21

If you are using the anterior or posterior approaches to the acetabulum

using a trochanteric osteotomy, the superior gluteal vessels must be

intact in order to avoid muscle necrosis of the gluteus medius and

minimus. This is because the origin and insertion of the muscles is

detached in these approaches. If the acetabular fracture involves a

displaced fracture of the greater sciatic notch, preoperative

angiography is advised to ensure that the neurovascular pedicle to

these structures is intact.

reaches the buttock beneath the lower border of the piriformis. It

enters the deep surface of the gluteus maximus almost immediately.

which follows the inferior gluteal nerve, supplies the gluteus maximus.

The branch it sends along the sciatic nerve was the original axial

artery of the limb. In rare cases, this artery can serve as one guide

to the sciatic nerve during surgery. The inferior gluteal artery may

also be torn in pelvic fractures, but not as frequently as the superior

gluteal artery.

encountered during the posterior approach to the hip because its course

in the buttock is very short. It turns around the sacrospinous ligament

before entering the perineum.

runs with the pudendal nerve. The artery is usually well clear of the

operative field during posterior approaches, but damage to it has been

reported. Local pressure against the ischial spine usually controls

bleeding; if not, or if the artery has retracted, an extraperitoneal

approach through the space of Retzius22 may be needed to ligate the parent trunk.

enters its muscle almost as soon as it emerges from behind the inferior

border of the piriformis. The nerve also supplies the superior gemellus.

which is formed by roots from the lumbosacral plexus (L4, L5, S1, S2,

S3), appears in the buttock from beneath the lower border of the

piriformis, just lateral to the inferior gluteal and pudendal nerves

and vessels. It is usually surrounded by fat and is often easier to

feel than to see. It passes vertically down the buttock together with

its artery, lying on the short external rotator muscles of the inner

muscular sleeve, the obturator internus, the two gemelli, and the

quadratus femoris. Farther distally, it passes deep (anterior) to the

biceps femoris and disappears from view, lying on the adductor magnus.

long as you are aware of its position. It can be injured if it is

trapped in the posterior blade of the self-retaining retractor that

holds the fascial edge. It also can be damaged if it is not protected

during reduction of the prosthetic head into the acetabulum.

hamstring muscles except the short head of the biceps femoris and the

extensor portion of the adductor magnus in the thigh. All its branches

arise from the medial side of the nerve. Dissections around the sciatic

nerve in the thigh therefore should remain on the lateral (safe) side,

since the only branch coming

off

that side runs to the short head of the biceps, a muscle that causes

few clinical problems if its nerve supply is damaged (see Fig. 8-54).

the terminal branches of the sciatic nerve, supply all the muscles

below the knee. In addition, they (and other sciatic branches) supply

skin over the sole of the foot, the dorsum of the foot (except for its

medial side), and the calf and lateral side of the lower leg. Damage to

the sciatic nerve at the level of the hip joint injures both tibial and

common peroneal elements, resulting in a balanced flaccid paralysis

below the knee, together with paralysis of the hamstring muscles.

Complete sciatic nerve lesions are relatively rare; more often, the

damage seems to affect either the tibial or the common peroneal

components. Hence, neurologic findings may vary regardless of the level

of the lesion.

approaches to the hip. The question then arises as to whether the nerve

was damaged at the operative site or whether it was compressed as it

turns around the fibular head, usually during postoperative care. The

differential diagnosis can be made by doing an electromyogram (EMG) of

the short head of the biceps, the only muscle of the thigh that is

supplied by the common peroneal division of the sciatic nerve. Lesions

in the pelvis or at the level of the hip joint denervate this muscle.

Lesions at the level of the fibular head leave it unaffected.

the hip joint is formed by nerve fibers. The remaining 80% is made up

of connective tissue. Nerve repairs in this area are often

unsuccessful, because bundle-to-bundle contact is difficult to achieve.

supplies a large area of skin on the back of the thigh. The nerve

actually lies on the sciatic nerve until the sciatic passes deep to the

biceps femoris. Then the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve continues

superficial to the hamstring muscles but deep to the fascia lata,

sending out several cutaneous branches.

emerges from the pelvis behind the sciatic nerve and runs with it on

its deep surface as it crosses the tendon of the obturator internus and

the two gemelli. The nerve then passes deep to the quadratus femoris

before entering its anterior surface. It also gives off muscular

branches to the inferior gemellus.

make a right-angled turn; it curves round the lesser sciatic notch of

the ischium. The muscle has a tricipital tendon that is reinforced at

its insertion by the superior and inferior gemelli.

Its transversely running fibers form a clear surgical landmark. The

muscle has an excellent blood supply. At the lower border of its

insertion lies the cruciate anastomosis, consisting of the ascending

branch of the first perforating artery, the descending branch of the

inferior gluteal artery, and transverse branches of the medial and

lateral femoral circumflex arteries (see Fig. 8-54).

In this maneuver, the quadrate tubercle of the femur is detached,

leaving the muscular insertion of the quadratus femoris intact. The

resultant muscle-bone pedicle can be swung upward, and the bone can be

inserted across the fracture site.

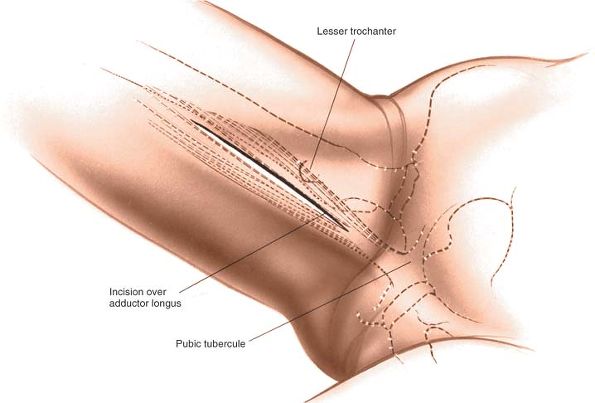

was originally designed for surgery on flexed, abducted, and externally

rotated hips, the kinds of deformities caused by certain types of

congenital dislocation of the hip.

-

Open reduction of congenital dislocation

of the hip. The approach gives an excellent exposure of the psoas

tendon, which can block reduction of the hip.24 -

Biopsy and treatment of tumors of the inferior portion of the femoral neck and medial aspect of proximal shaft

-

Psoas release

-

Obturator neurectomy

obturator neurectomy. If a neurectomy is combined with an adductor

release, the approach can be performed through a short transverse

incision or a short longitudinal incision in the groin that permits

division

of the adductors close to their pelvic origin, an area where there is less bleeding.

|

|

Figure 8-57 Position of the patient on the operating table for the medial approach to the hip.

|

affected hip flexed, abducted, and externally rotated. This may not be

possible in cases with fixed deformity, when the position is often

determined for you. The sole of the foot on the affected side should

lie along the medial side of the contralateral knee (Fig. 8-57).

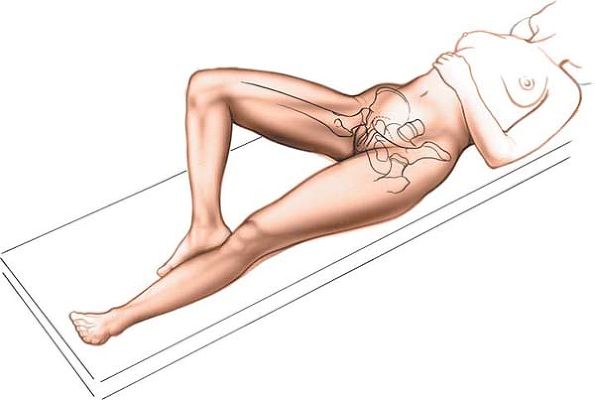

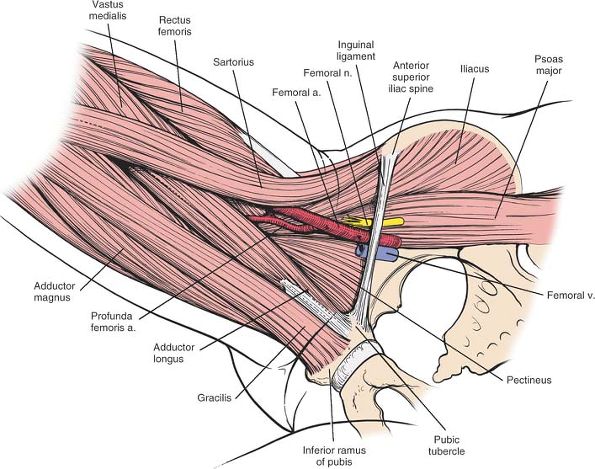

from the medial side of the thigh and follow it up to its origin at the

pubis, in the angle between the pubic crest and the symphysis. The

adductor longus is the only muscle of the adductor group that is easy

to palpate.

move your thumb along the inguinal creases medially and obliquely

downward until you can feel the pubic tubercle. They are at the same level as the top of the greater trochanter.

thigh, starting at a point 3 cm below the pubic tubercle. The incision

runs down over the adductor longus. Its length is determined by the

amount of femur that must be exposed (Fig. 8-58).

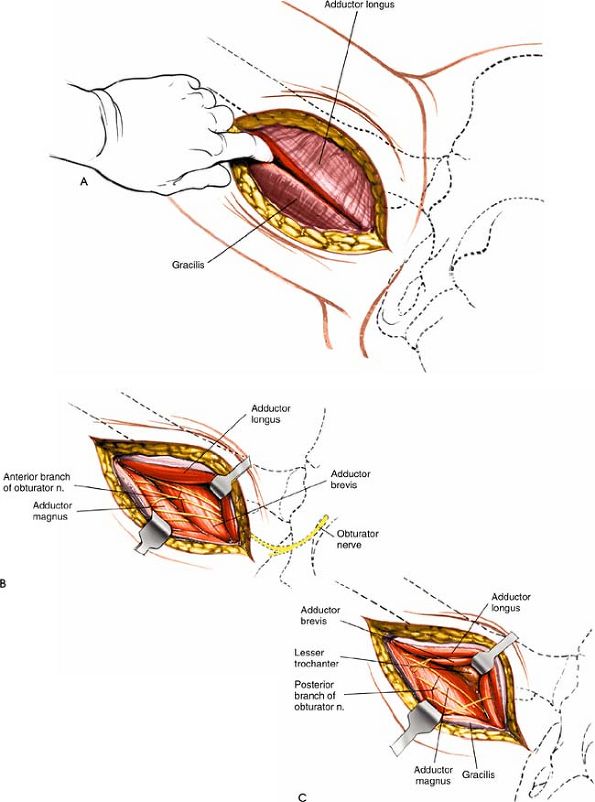

internervous plane, since both the adductor longus and the gracilis are

innervated by the anterior division of the obturator nerve. The plane

is nevertheless safe for dissection; both muscles receive their nerve

supplies proximal to the dissection (Fig. 8-59).

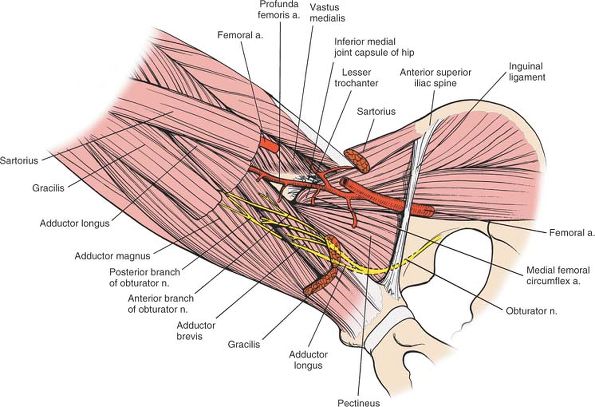

adductor brevis and the adductor magnus. The adductor brevis is

supplied by the anterior division of the obturator nerve. The adductor

magnus has two nerve supplies: Its adductor portion is supplied by the

posterior division of the obturator nerve, and its ischial

portion

is supplied by the tibial part of the sciatic nerve. The two muscles,

therefore, form the boundaries of an internervous plane (see Fig. 8-62).

|

|

Figure 8-58 Incision for the medial approach to the hip.

|

|

|

Figure 8-59

The intermuscular interval between the adductor longus and the gracilis is not an internervous plane because both muscles are innervated by the anterior division of the obturator nerve. The plane is safe, however, because the muscles receive their nerve supplies proximal to the dissection. |

|

|

Figure 8-60 (A) Develop the plane between the gracilis and the adductor longus. (B)

Retract the adductor longus and the gracilis to reveal the adductor brevis with the overlying anterior division of the obturator nerve. (C) Retract the adductor brevis from the muscle belly of the adductor magnus to uncover the posterior division of the obturator nerve. Note the lesser trochanter in the depths of the wound. |

between the gracilis and the adductor longus. Like other intermuscular

planes in the adductor group, this plane can be developed with your

gloved finger (Fig. 8-60A).

adductor brevis and the adductor magnus until you feel the lesser

trochanter on the floor of the wound. Try to protect the posterior

division of the obturator nerve, the innervation to the muscle’s

adductor portion, to preserve the hip extensor function of the adductor

magnus (see Dangers below). Place a narrow retractor (such as a bone spike) above and below the lesser trochanter to isolate the psoas tendon.

|

|

Figure 8-61

Anatomy of the medial approach to the hip. The thigh is abducted, slightly flexed, and externally rotated. The plane of the superficial dissection runs between the adductor longus and the gracilis. |

lies on top of the obturator externus and runs down the medial side of

the thigh between the adductor longus and the adductor brevis, to which

it is bound by a thin tissue. It supplies the adductor longus, the

adductor brevis, and the gracilis in the thigh (Fig. 8-60B).

lies in the substance of the obturator externus, which it supplies

before it leaves the pelvis. The nerve then runs down the thigh on the

adductor magnus and under the adductor brevis; it supplies the adductor

portion of the adductor magnus (Fig. 8-60C).

|

|

Figure 8-62

The muscular layer of the medial approach to the hip. The dissection lies between the adductor brevis and the adductor magnus. The gracilis, adductor longus, and sartorius have been resected to reveal the deeper structures of the medial aspect of the thigh. Note the relationships of the anterior and posterior divisions of the obturator nerve to the adductor longus and adductor brevis. Note the proximity of the medial femoral circumflex artery to the insertion of the psoas tendon. Psoas Major. Origin. Anterior surface of transverse processes and bodies of the lumbar vertebrae and corresponding intervertebral disks. Insertion. Lesser trochanter of femur. Action. Flexor of hip and flexor of lumbar spine when leg is fixed. Nerve supply. Segmental nerves from second and third lumbar roots.

Iliacus. Origin.

Upper two thirds of iliac fossa, inner lip of iliac crest, anterior aspect of sacroiliac joint, and from the lumbosacral and iliolumbar ligaments. Insertion. Lesser trochanter of femur by common tendon with psoas. Action. Flexor of hip. Tilts pelvis forward when leg is fixed. Nerve supply. Femoral nerve (L2-L4). |

to cut these nerves to relieve muscular spasticity. If you are not

using it for that purpose, avoid transecting them.

passes around the medial side of the distal part of the psoas tendon.

It is in danger, especially in children, if you try to detach the psoas