SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF DEGENERATIVE SCOLIOSIS

VIII – THE SPINE > Spinal Deformity > CHAPTER 160 – SURGICAL

MANAGEMENT OF DEGENERATIVE SCOLIOSIS

the adult secondary to degenerative disc disease. It may be difficult

in many cases to determine whether scoliosis is arising de novo

or if patients had mild to moderate degrees of scoliosis that became

symptomatic or progressed late in adulthood. The treatment of

degenerative scoliosis follows many of the same principles as the

treatment of adult idiopathic scoliosis, however, so the distinction in

many cases may be moot. This chapter discusses the factors that should

be considered in treating patients with this condition.

not progress, and they may not be symptomatic. With more advanced

disease, axial pain and neurogenic claudication are typical symptoms.

As with any degenerative spine disease, facet hypertrophy, diffuse disc

bulges, disc degeneration, and narrowing and redundant ligamentum

flavum can result in spinal stenosis and produce symptoms of neurogenic

claudication and radiculopathy (25). The degree

of compression can be aggravated in the presence of lateral listhesis

or spondylolisthesis, by traction on the nerve roots.

another occurs in the coronal plane, appears to correlate with a

greater risk of curve progression (25,27).

Significant lateral listhesis, particularly when it occurs at multiple

adjacent levels, can result in significant truncal imbalance with

resultant pain and fatigue. In many patients, these symptoms can be

managed conservatively with anti-inflammatories, physical therapy, and

epidural steroids. With progression of the patient’s curvature,

however, failure to respond to conservative measures or significant

compromise of the patient’s quality of life may call for consideration

of surgical intervention.

Risk factors for curve progression include curve magnitude greater than

30°, osteoporosis, and lateral listhesis or rotatory spondylolisthesis (9,14).

Prior decompressive surgery, such as a laminectomy, can increase curve

progression as well, sometimes secondary to development of a

postsurgical fracture of the pars interarticularis and

spondylolisthesis. Rapid progression of scoliosis in a patient with a

prior laminectomy is highly suspect for a pars fracture, which should

be sought in the workup of such a patient.

with a lateral wedge component may aggravate or cause development of

scoliosis. These patients may have a relative loss of lumbar lordosis

as well. Patients with lateral listhesis appear to be at greater risk for curve progression (25,27),

and, in addition, they are subject to traction on their nerve roots at

the involved levels. Asymmetric wear on the facet joints may contribute

to facet arthropathy, leading to central or foraminal stenosis.

Although most patients present with pain secondary to nerve root

compression, others present with weakness. Pain and weakness may be

particularly intractable from severe disc space collapse, with or

without listhesis, and decreasing space between the adjacent pedicles

results in foraminal stenosis. Patients with stenosis secondary to

degenerative scoliosis suffer a similar pathophysiology as a cause of

their neurogenic claudication—namely, a vascular insufficiency to the

neural elements secondary to the stenosis, which is generally worsened

by lumbar extension.

claudication occur in similar patient populations, and it is important

to distinguish the true cause of the patient’s leg pain. A careful

history, palpation of distal pulses, examination of feet and skin, and,

if indicated, referral to a vascular specialist may be needed. In

general, neurogenic claudication is improved by forward flexion of the

spine, including sitting, and it may be worse going downhill because

hyperextension is necessary (see Chapter 147).

However, at least some patients with stenosis secondary to degenerative

scoliosis have reported that their extremity symptoms are not reliably

relieved by forward flexion (11).

according to the conditions that cause the most symptoms. For example,

the patient with more back pain secondary to the degenerative disease

can be managed successfully using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories,

rest, physical therapy, cardiovascular conditioning, and, occasionally,

bracing. Patients with neurogenic claudication may respond to any of

these measures but may receive relief from epidural cortisone

injections. Bracing can be used on occasion for the patient with mild

degenerative scoliosis with back pain only. Rigid bracing has not been

shown to prevent progression in adults with scoliosis. However, bracing

may be a reasonable alternative for a patient who has a degenerative

scoliosis with mild to moderate progression, but who is medically

unable to tolerate a major reconstructive procedure.

orthosis for more severe scoliosis or kyphosis, or it may simply be a

lightweight, corset-type brace for milder curves. However, since

symptom improvement is the primary goal, rather than curve control,

results with a specific patient will be the final determining factor.

neurologic deterioration are the main indications for surgical

intervention. In general, bracing in adults is discouraged because it

does not halt progression and may result in patient dependence on the

brace and associated trunk deconditioning. However, in certain cases,

such as an elderly patient who is too ill to tolerate a major surgical

procedure, or a patient whose severely osteoporotic bone is too weak to

support instrumentation, bracing may slow progression or attenuate the

pain symptoms.

improved by stabilization and fusion of her degenerative scoliosis can

be difficult. Once surgery has been deemed likely to help such a

patient, however, choice of the fusion levels requires consideration of

curve pattern, sagittal and coronal balance, pain locale, levels

needing decompression, and the presence of degenerated or listhetic

levels, as well as patient expectations and activity levels. Facet

blocks, discography, and nerve root blocks may be helpful in

determining symptomatic levels, although their predictive value for

fusion surgery has not been proven. Grubb et al. (12)

used provocative discography to help determine fusion levels in adult

scoliosis patients (degenerative and idiopathic) and felt that this

aided them in their surgical planning. However, in their study, all

positive discograms were at morphologically abnormal levels, and it is

not clear whether they might have included such levels based on

radiographic or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)–determined

degenerative levels. Fortunately, fusion for back pain secondary to

scoliosis appears more predictable than fusion for back pain secondary

to degenerative disc disease without deformity. We do not routinely

perform discography in these patients, because it

has not proven of benefit in predicting the outcome of fusion surgery.

claudication should have their stenosis decompressed concurrently with

stabilization of the curvature. In most patients, an MRI will give

adequate information for localization of stenotic levels; in some

patients, however, the lateral deformity or rotatory component

precludes clear delineation of the anatomy. In these cases, computed

tomography (CT) or myelography is indicated for preoperative planning.

neurogenic claudication, and only mild degrees of scoliosis, it may be

reasonable to address the compressive symptoms with laminotomy,

laminectomy, or foraminotomy as needed. Aggressive decompression can

result in curve progression; this isolated procedure should be reserved

for milder cases in which limited decompression can be expected to help

the patient. Be sure the patient understands the possibility of curve

progression and recurrence of symptoms.

alone may be sufficient. The majority of patients with degenerative

scoliosis will require instrumentation and grafting to achieve fusion

over multiple segments that require stabilization. Because of the

increased pseudarthrosis rate with multiple-level fusions, it is rare

to have a patient who can be managed without instrumentation. However,

certain older patients, particularly the medically fragile, may better

tolerate laminectomy and limited uninstrumented fusion (i.e., at the

level where there is a degenerative spondylolisthesis). In some

patients, moderate to severe osteoporosis may preclude fixation, but,

as with laminectomy alone, there is a risk of curve progression and

recurrence of symptoms. Therefore, this approach is limited to patients

who clearly understand the limitations of what surgery can accomplish

for them and are willing to risk recurrent symptoms. In general, we

have not found age or osteopenia to be a contraindication for fusion

with instrumentation.

several factors. The levels that should be fused should include at

least the entirety of the symptomatic curve, but often additional

levels must be included to address symptomatic degenerative levels and

permit maintenance or restoration of coronal and sagittal balance.

Generally, preoperative bending films can help predict the amount of

correction that can be obtained after exposure, facetectomy, and

application of appropriate corrective forces. The end vertebra,

particularly distally, should be a vertebra that is level on side

bending. Sagittal balance is exceedingly important to consider,

particularly because many of these patients have osteoporosis. Most

degenerative curves are kyphotic; if the kyphosis is not flexible, a

combined anterior–posterior approach may be indicated to achieve

sagittal realignment and successful arthrodesis. It is also important

not to end the fusion at a kyphotic segment. Many of these patients

have lumbar or thoracolumbar curvatures, and including only the major

curve often can result in ending the fusion at the mid or lower

thoracic spine—in the middle of the kyphosis. Such patients are at

considerable risk for development of progressive junctional kyphosis,

and in general it is best to include the minor compensatory thoracic

curve and end the fusion at the end vertebra of the kyphosis (usually

T-4 or T-5).

nonkyphotic thoracolumbar junction can the fusion safely stop at the

thoracolumbar junction. Choosing the distal end vertebra can be

difficult in the patient with degenerative scoliosis and low back pain.

Deciding whether L-4–L-5 and/or L-5–S-1 is symptomatic is crucial

because long fusions to the sacrum generally necessitate combined

anterior and posterior surgery and have a higher rate of complications.

Not including a symptomatic level will result in limited pain relief,

however, and thus it will decrease the success of the surgery. In

addition, fusions ending at L-4 or L-5 are at risk for development of

symptomatic degeneration below the fusion. This development 5–10 years

after the surgery may be acceptable for the older patient, but its

occurrence 2 years or so after the surgery is not. Therefore, consider

whether a more distal fusion is indicated. Involvement of the

lumbosacral region is very common in degenerative scoliosis, and the

majority of these patients require combined anterior and posterior

spinal fusion to the sacrum.

hook-and-rod systems are preferred for instrumentation of degenerative

scoliosis. These systems allow much better correction of coronal and

particularly sagittal plane deformity. However, such surgery is

technically demanding, and the surgeon must have a clear understanding

of the corrective forces that should be applied and how they affect the

patient’s curvature, coronal balance, sagittal balance, and shoulder

obliquity. The following considerations are important:

-

It is rare to be able to perform rod rotation in the patient who has degenerative scoliosis.

-

If the patient has significant

osteoporosis, and multiple-level laminectomy is not required for

coexisting spinal stenosis (see below), consider using sublaminar wires

supplemented by hooks and/or pedicle screws at strategic levels

(generally the end vertebra of each curve and sometimes the apical

vertebra as well). Such wires are quite easy to attach to rods and, for

an osteoporotic patient whose trabecular bone has numerous vascular

channels, their use can potentially decrease operative time and

therefore decrease blood loss. -

Do not affix rods to end vertebrae with

sublaminar wires, because wires do not provide axial control of the

spine and can allow axial collapse and subsequent junctional kyphosis.

Use pedicular fixation or hook combinations at the ends of constructs

to decrease the likelihood of this problem. -

To ensure coronal balance, we prefer to

obtain intraoperative long radiographs of the entire spine after the

correction has been partially or completely performed. Adjustments in

the corrective forces can be made at this time if desired. -

Although in situ

bending to fine-tune the coronal balance can be performed in some adult

scoliosis patients, most patients with degenerative scoliosis have

osteoporotic bone, and in situ bending can result in loss of fixation.

spinal stenosis as part of their degenerative process. As part of

preoperative planning, evaluate with an MRI or CT/myelogram any patient

with degenerative scoliosis who notes leg pain or buttock pain. As

previously noted, the MRI is adequate for many patients; with greater

degrees of curvature, however, CT/myelography gives better bony detail

and permits better understanding of the anatomy in the presence of the

curvature. It is important to identify symptomatic levels of stenosis

so that decompression can be performed at the time of posterior fusion.

In most cases, this can be determined anatomically according to

dermatomal levels and nerve root distributions; however, occasionally,

selective nerve root injections may be needed to determine which levels

with mild to moderate degrees of stenosis are the symptomatic ones.

pedicle screw instrumentation may be needed to attain fixation.

Generally, fusion rates are improved with instrumentation, particularly

in patients with conditions such as degenerative scoliosis (13).

As with deformity surgery in general, try to visualize the medial wall

of the pedicle before screw placement, to correctly account for spinal

rotation. This is a simple matter after laminotomy or laminectomy has

already been performed. Frazier et al. (8)

reported on patients who underwent decompression for spinal stenosis,

including 19 who had at least 15° of scoliosis preoperatively. The

majority of their patients with scoliosis did not have fusion performed

at the time of decompression. They found that a greater degree of

preoperative scoliosis was associated with less improvement in back

pain. We have not found curve severity to correlate with outcomes of

reconstructive surgery in these patients. We do take a more aggressive

approach, however, preferring to fuse patients with scoliosis who are

undergoing a laminectomy even if the underlying medical condition

permits only limited fusion.

with degenerative scoliosis will require anterior and posterior

procedures to achieve fusion, as well as coronal and sagittal balance.

There are several indications for combined techniques in this complex

patient population.

-

Inflexible sagittal-plane imbalance is

one of the most common indications for combined surgery. Relative

lumbar kyphosis must be corrected to achieve sagittal plane balance.

The use of structural allografts facilitates the restoration of lumbar

lordosis. We favor femoral allografts, packed with autogenous

cancellous graft; Harms-type mesh cages with autograft may also be

used. Consideration of the scoliotic deformity is necessary; otherwise,

mere placement of the structural grafts on the side of the

approach—usually the curve convexity—will limit correction of the

scoliosis. -

Degenerative curves of significant

magnitude, especially with limited flexibility, may also require

combined surgery. Coronal imbalance may also indicate the need for

combined surgery. -

Patients who require a long fusion to the

sacrum should also have a combined procedure because posterior fusion

alone in this setting has a high incidence of failure (4,12).

Most of these patients have significant degeneration across the

lumbosacral junction, and many also have thoracolumbar kyphosis (which

is a contraindication for ending the fusion at the thoracolumbar

junction), so combined surgery is frequently indicated. -

In patients who have had failed posterior instrumented fusions, consider combined surgery. We and others (1,10,23) have found iliac fixation in the form of Galveston rods or iliac screws to be useful for achieving distal

P.4119

fixation (Fig. 160.1).

For patients with reasonable bone quality, anterior structural

allograft at the lumbosacral junction coupled with sacral screws alone

that penetrate the anterior cortex may be adequate. Others (2,7,16,17) have used iliosacral screws or intrasacral screws (Jackson technique) for distal fixation. Figure 160.1.

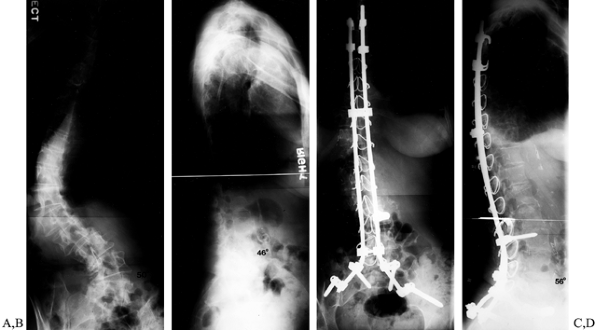

Figure 160.1.

This 71-year-old woman was first diagnosed with scoliosis at age 45. In

the 5 years previous to presentation at this institution, she developed

increasing low back pain and increasing prominence of her right hip.

Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B)

standing radiographs demonstrate degenerative scoliosis with collapsing

curve. The patient underwent a staged anterior and posterior spinal

fusion, T-5 to the sacrum; the posterior fusion included multiple

sublaminar wires and iliac screws. Her postoperative course had some

brief episodes of cardiac ectopy and a urinary tract infection.

Postoperative radiographs (C,D) demonstrate

correction of the deformity, with coronal and sagittal balance

achieved. At 2-year follow-up, she was doing well, with excellent

improvement of her function and marked pain relief.

fixation is preferred for combined surgery in this patient population.

Sublaminar wires may be used as a component of the fixation, but use

fixed components (hooks in a claw construct in the mid and upper

thoracic spine, pedicle screws at the thoracolumbar junction) at the

proximal end of the construct to decrease the risk of junctional

kyphosis.

procedures under a single anesthetic to lower overall incidence of

complications, nutritional depletion, and blood loss (5,21,24).

Older patients, particularly those with coexisting medical conditions

or significant osteoporosis, may be less able to tolerate the lengthy

anesthetic, however. Older patients with significantly osteoporotic

bone may experience increased blood loss, which can lead to development

of a coagulopathy during a prolonged procedure.

cannot be completed in 8–10 hours, then stage the procedure. The

scheduled delay between stages may be 3–7 days, depending on coexisting

medical conditions, the age of the patient, and scheduling issues. The

occurrence of complications, however, may further delay the

second-stage procedure.

depletion, which may lead to an increased incidence of infection,

pneumonia, and urinary tract infection (5,21,24). We have shown that, particularly in the older patient population, use of total parenteral nutrition may decrease the

rate of nutritional depletion, which may in turn decrease the risk of complications (15).

average of 70% reduction of pain in patients fused for painful

degenerative scoliosis, which is somewhat less than that seen for

patients fused for painful adult idiopathic scoliosis (80% pain relief).

-

Perform a standard thoracoabdominal or

retroperitoneal approach on the convexity of the curve to be addressed.

Be sure to prep down to the pubic symphysis if L-5–S-1 is to be fused,

as is the case in most of these patients. -

Identify segmental vessels and ligate or

clip. Sweep the psoas muscle posteriorly, using bipolar cautery to

control bleeding. Use blunt but careful dissection to sweep the great

vessels forward. The common iliac will need to be mobilized if L-4–L5

or L-5–S-1 is to be exposed. This generally requires ligating the

recurrent lumbar vein. -

Incise the disc space with a #11 blade.

Use a rongeur to remove loose disc material, and a rongeur or osteotome

to remove the osteophyte so that the endplate can be visualized. Peel

the disc from the endplate using a Cobb elevator—exercise care in

patients with osteoporosis. -

Remove additional disc material with a

curved or straight curette, supplementing with a rongeur. A Blount

spreader may be used with care to keep the disc space from collapsing

in the convexity. The release must extend across to the contralateral

annulus. If there is significant kyphosis, divide the anterior

longitudinal ligament. -

The distalmost levels generally are in

the fractional curve and also are most important for maintaining

lordosis. Therefore, placement of the structural allograft should not

block correction. If disc spaces in the convexity are to be placed,

take care to place them as far toward the concavity as possible; do not

place so large a graft that correction is blocked. For disc spaces that

are not to receive structural allograft, pack morcelized cancellous

bone lightly within, preferably autograft, although allograft can be

used. -

Measure the height of the disc space to

be filled with allograft. We use femoral shaft pieces cut at the time

of surgery to fit the evacuated disc space. (Other surgeons prefer mesh

cages.) The graft should be snug but not overly tight; that is, the

release should open the disc space, not the graft itself. After

confirming the size, fill the marrow cavity of the femoral allograft

with rib graft or local bone graft, or morcelized cancellous allograft,

and impact gently into place. Forcing an overly large graft or

inadequate release will result in graft breakage (with high risk for

pseudarthrosis) or endplate fracture (with increased risk for

subsidence). -

Use interference screws to prevent

allograft migration. Place a 6.5 mm cancellous screw with a plastic

washer lateral to the graft, into the vertebral body. Alternatively, a

long enough screw can be placed lateral to the adjacent graft,

skewering the graft below, to prevent migration of two allografts. It

may be necessary to burr a small impression into the lateral aspect of

the adjacent allograft to allow the washer to seat snugly. Although

theoretically possible, we have not generally found that these screws

impair our ability to place pedicle screws during the posterior

instrumentation. Since instituting the use of these interference

screws, we have not needed to replace anterior structural allograft.

-

Osteoporotic bone is nearly always

present and its vascular channels can contribute to greater bleeding

rates than seen in the patient with normal bone. -

Many of these patients may have chronic

hypertension, coronary artery disease, or other vascular conditions

that contraindicate or limit the use of controlled hypotension to

decrease surgical blood loss. -

One must select fusion levels carefully. Ending the fusion at a kyphotic level can lead to junctional kyphosis.

-

Although sublaminar wires may be

preferred in many patients because their use spreads corrective forces

over many levels, they should not be used at the end vertebra because

they do not control the spine in the axial plane; they may also result

in junctional kyphosis. Use hooks or screws at the ends of the

construct. -

Overcorrection of the curve may lead to truncal imbalance, which, if significant, may require revision surgery.

-

Patients who undergo fusion surgery are

at risk for developing degeneration above or below the fusion. Consider

including severely degenerated adjacent levels to avoid rapid

development of this problem. Extending the fusion should be balanced by

the consideration of how much surgery should be done on the older, less

healthy patient. -

Although osteoporotic patients have not

been shown to have a higher rate of pseudarthrosis, poorer fixation due

to poor bone quality, combined with autogenous bone graft from a site

with more fat infiltration and fewer osteoprogenitor cells, is of

concern.

undergoing spinal surgery is about 60% (6,12,18,19,22).

Although the rate is not significantly greater with increasing age

(60–70 years, 70–80 years), there is no doubt that older patients are

less able to tolerate complications and recover quickly from them. Keep

this in mind when planning the surgery. We have shown that older

patients may be more at risk for development of complications such as

pneumonia and urinary tract infections, particularly if they are

undergoing staged surgery. Consider nutritional supplementation to

decrease their risk of nutritional depletion (15).

Thromboembolic disease leading to pulmonary embolism occurs more

commonly in older patients, particularly after combined anterior and

posterior surgery (3). Our current practice is

to use elastic stockings and sequential compression boots for

prophylaxis of deep venous thrombosis. We remain vigilant in patients

who have combined surgery, but we do not routinely anticoagulate these

patients.

published studies in this patient population include small numbers of

patients, we estimate it to be 1% to 5%. Discuss fully the numerous

potential risks of spinal surgery with the patient, as well as her

family, if desired, when she is offered any spinal surgery.

suggested that endoscopic surgery, both thoracoscopy and lumbar

endoscopy, may result in lower morbidity and decreased length of

hospital stay (20,26).

Unfortunately, such techniques are difficult to learn and have not yet

been proven to demonstrate comparable fusion rates to that achieved in

open procedures. In general, for degenerative scoliosis, the indicated

anterior procedure is in the lumbar or lumbosacral spine. Currently,

most of the lumbar endoscopic techniques have concentrated on

screw-in–type cages, which are not well suited for degenerative

scoliosis because of the presence of multiplanar deformity.

scoliosis is complex and requires a thorough understanding of a

multitude of factors, including pain sources, coronal and sagittal

balance, fusion techniques, indications for decompression, indications

for combined anterior and posterior surgery, and instrumentation

choices, as well as the potential for complications. With appropriate

patient selection, however, and realistic expectations of surgery on

the part of both the patient and the surgeon, the majority of patients

will have a satisfactory outcome.

scheme: *, classic article; #, review article; !, basic research

article; and +, clinical results/outcome study.

O, Dendrinos G, Ogilvie J, et al. Management of Adult Spinal Deformity

with Combined Anterior-posterior Arthrodesis and Luque-Galveston

Instrumentation. J Spinal Disorder 1991;4:131.

JF, Caudle R, Ashmun RD, Roach J. Immediate Complications of

Cotrel-Dubousset Instrumentation to the Sacro-pelvis: A Clinical and

Biomechanical Study. Spine 1990;15:932.

D, Lipson S, Fossel A, et al. Associations between Spinal Deformity and

Outcomes after Decompression for Spinal Stenosis. Spine 1997;22:2025.

S, Fontaine F, Kelley B, et al. Nutritional Depletion in Staged Spinal

Reconstructive Surgery: The Effect of Total Parenteral Nutrition. Spine 1998;23:1401.

RP, Ebelke DK, McManus AC. Clinical Results and Standing Radiographic

Sagittal Plane Analysis in Spondylolisthesis Insrumented to the Sacrum

with New Techniques. Orthop Trans 1995–1996;19:593.

BR, Tolo VT, McAfee PC, Burest P. Nutritional Deficiencies after Staged

Anterior and Posterior Spinal Reconstructive Surgery. Clin Orthop 1988;234:5.

ET, Krengel WF, King HA, Lagrone MO. Comparison of Same-day Sequential

Anterior and Posterior Spinal Fusion with Delayed Two-staged Anterior

and Posterior Spinal Fusion. Spine 1994;19:1256.

J, Ben-Yishay A, Mack M. Video-assisted Thoracoscopic Excision of

Herniated Thoracic Disc: Description of Technique and Preliminary

Experience in the First 29 Cases. J Spinal Disord 1998;11:183.