Tibial Torsion

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Tibial Torsion

Tibial Torsion

Paul D. Sponseller MD

Description

-

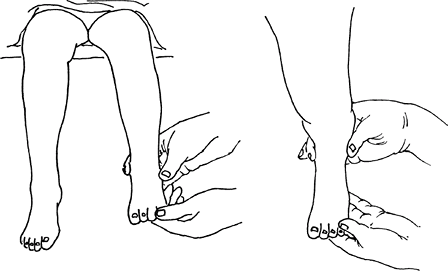

A condition in which the tibia, along

with the ankle and foot, is rotated internally or externally (i.e.,

inward or outward) on its axis (Fig. 1) -

This rotation is seen in the course of normal development, but on occasion it may represent a developmental abnormality.

-

Abnormal values usually are described as >2 standard deviations from the mean for a given age.

-

Classification:

-

Internal tibial torsion

-

External tibial torsion

-

Neuromuscular torsion: May be associated with cerebral palsy or spina bifida

-

-

Synonyms: In-toeing (internal torsion or “pigeon toeing”); Out-toeing (external torsion)

Epidemiology

-

Abnormal internal or external tibial torsion as an isolated deformity is common (1,2).

-

Usually seen in infants and children <3 years old, after walking has developed

-

In general, younger children display more internal than external rotation.

-

No particular predilection for males or females has been noted.

-

Incidence

Persistent torsion that does not resolve is seen in <1% of children (2).

Risk Factors

Genetics

-

Internal tibial torsion is presumed to be caused by a combination of genetic factors and intrauterine position.

-

A family history is important because the

subdivision into hereditary and nonhereditary forms is of practical

importance in the prognosis and treatment.

Etiology

Caused by a combination of genetic factors and intrauterine position

|

|

Fig. 1. Internal tibial torsion is characterized by inward rotation of the foot with respect to the knee.

|

Associated Conditions

In infants, abnormal medial tibial torsion may coexist with congenital metatarsus varus or developmental genu varum.

Signs and Symptoms

-

Parents often are concerned about the

difference between a child with tibial torsion and other siblings who

do not have this condition. -

A parent who was treated for the same condition with an orthosis may believe that the child will require the same treatment.

-

The primary concern often is the appearance of the child’s legs while walking or running.

-

Tripping and falling may be noticed by the parent.

-

Pain is rare; parents may describe the child as having a limp, but no painful component to the gait is present.

Physical Exam

-

Assess the child from the hips to the toes.

-

1st, if the child is ambulatory, observe the child’s gait, which usually demonstrates the problem that concerns the parents.

-

Look for a heel-toe gait and a limp:

-

The absence of a heel-toe gait may be the initial sign of an underlying neurologic disorder (e.g., cerebral palsy).

-

A limp may explain the rotational

position of the extremity because the child may be positioning the limb

in a more comfortable position to avoid pain while walking. -

Unilateral DDH of the hip may present as in-toeing associated with a limp.

-

-

Foot-progression angle:

-

Observe the angle between the long axis of the foot and the line of progression the child is moving along.

-

The normal foot-progression angle is slightly external, but has a range of ~15° in either direction.

-

-

-

Then, the child should lie down for the rest of the examination.

-

Check the child’s hips for stability in the supine position before specifically assessing for rotational malalignment.

-

Then place the child in a prone position to evaluate hip rotation and tibial torsion.

-

For proper measurement, the pelvis must remain level and stationary during the examination.

-

Note the clinical estimates of femoral anteversion and tibial torsion.

-

Femoral anteversion is estimated by the

angle between the vertical axis and the long axis of the leg at the

position in which the greater trochanter is the most prominent on

internal and external rotation. -

Tibial torsion can be assessed by comparing the bimalleolar axis with the position of the tibial tubercle.

-

-

Note the foot shape: Metatarsus adductus may be the primary cause of in-toeing, particularly in the infant.

-

Tests

Imaging

-

Physical examination usually provides the

information needed to form a treatment plan, but radiographs are

indicated in some instances. -

Radiography:

-

If asymmetric limitation of hip abduction

is present or if hip abduction in the toddler is <60°, an AP

radiograph of the pelvis is needed to rule out hip dysplasia. -

Radiographs of the feet may help to quantify clinically suspected metatarsus adductus.

-

Radiographs of the tibia are not helpful in assessing tibial torsion.

-

-

CT is the most widespread imaging

technique for evaluating femoral rotation, but this test often is

unnecessary because these conditions usually can be evaluated

clinically.

Differential Diagnosis

-

Blount disease (pathologic genus varum with internal tibial torsion)

-

Abnormal femoral anteversion

-

Metatarsus adductus

-

Cerebral palsy

-

Hip dysplasia

P.463

General Measures

-

Internal tibial torsion is the most common cause of in-toeing in children <3 years old (2).

-

With increasing age and growth, tibial

torsion tends toward a normal tibial position, with the lateral

malleolus 20–30° posterior to the medial malleolus. -

Virtually all children born with internal tibial torsion have improvement by age 3–5 years.

-

Most nonsurgical treatment consists of a

careful explanation to the parents of the course of in-toeing or

out-toeing in the examined child, because most rotational concerns

normalize with time and growth. -

Because the use of night splints (i.e.,

Dennis Browne bars), braces, heel or sole wedges, or orthotics has not

been proven to influence rotation of the tibia (2), most orthopaedic surgeons do not use these devices. -

In children born with excessive external

tibial torsion, particularly if it is asymmetric, spontaneous

correction is less common, and rotational osteotomy may be needed later

(3). -

For children with excessive or asymmetric

tibial torsion after age 7–10 years, derotational tibial osteotomy may

be considered if the parents are concerned about the gait. -

Often, the persistence or worsening of

in-toeing beyond 3–4 years of age is the result of the emergence of

abnormal femoral anteversion. -

Children born with “normal” external

tibial torsion usually do not undergo additional external rotation

during the 1st few years of life, and the final tibial torsion stays

within the normal range.

Activity

No particular modification is needed.

Special Therapy

Physical Therapy

-

Formal physical therapy usually is not indicated or beneficial.

-

The time frame for improvement in torsion, which is measured in years, is not compatible with physical therapy.

-

-

Some physicians advise parents to involve

the children in activities for which foot position is important, such

as ice skating, roller skating, track, or ballet.-

Although little evidence suggests that

these activities produce correction, such activities encourage parents

to monitor the limbs and shows the child’s functional potential.

-

Surgery

-

Derotation osteotomy is the only surgical treatment to consider for children with rotational abnormalities.

-

However, surgery should be considered only after age ~7–10 years.

-

Before surgery, the clinician must be

certain that the expected natural derotation will not correct the

rotational abnormality sufficiently.

-

-

In general, tibial rotational osteotomy seldom is needed in children <5 years old.

-

In children with cerebral palsy, early surgery is more likely to be followed by recurrence of the torsion.

-

Tibial derotation osteotomy may be

appropriate if the thigh–foot angle remains internally rotated ≥20° or

if the external tibial rotation is ≥35°.-

However, this decision is an elective best left up to the family.

-

-

Rotational osteotomy is performed most

commonly just above the distal tibial growth cartilage and is

immobilized with a cast with or without internal fixation for 6–8 weeks.

Prognosis

-

This condition usually is self-limiting and part of natural development.

-

If the tibias of the parents and the

adolescent siblings have normal alignment, the probability of

spontaneous correction in the affected child by the age of 7–8 years is

great (1). -

If a familial incidence of persistent

abnormal internal tibial torsion exists, the prognosis for spontaneous

correction is slightly lower (1).

Complications

Potential surgical complications include growth-plate injuries, neurovascular injuries, nonunion, and implant problems.

Patient Monitoring

Annual or biannual observation and examination are

useful for documenting the expected rotational changes with growth,

particularly if the parents need periodic reassurance.

useful for documenting the expected rotational changes with growth,

particularly if the parents need periodic reassurance.

References

1. Schoenecker

PL, Rich MM. The lower extremity. In: Morrissy RT, Weinstein SL, eds.

Lovell and Winter’s Pediatric Orthopaedics, 6th ed. Philadelphia:

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006:1157–1211.

PL, Rich MM. The lower extremity. In: Morrissy RT, Weinstein SL, eds.

Lovell and Winter’s Pediatric Orthopaedics, 6th ed. Philadelphia:

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006:1157–1211.

2. Staheli LT, Corbett M, Wyss C, et al. Lower-extremity rotational problems in children. Normal values to guide management. J Bone Joint Surg 1985;67A:39–47.

3. Wedge JH, Munkacsi I, Loback D. Anteversion of the femur and idiopathic osteoarthrosis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg 1989;71A:1040–1043.

Codes

ICD9-CM

736.89 Internal tibial torsion

Patient Teaching

-

Education of the parents is of paramount importance in managing family concerns.

-

Most patients with tibial torsion improve to a satisfactory degrees naturally.

-

Showing a graph of the normal improvement with age may be helpful.

FAQ

Q: By what age should my child’s torsion improve?

A:

Every child is different. as long as improvement is seen, continued

watching and waiting is appropriate. If no improvement is seen by age

8–10 years, surgery may be justified if the parents are interested.

Every child is different. as long as improvement is seen, continued

watching and waiting is appropriate. If no improvement is seen by age

8–10 years, surgery may be justified if the parents are interested.

Q: Does internal or external tibial torsion pose a risk of arthritis of the knee, hip, or back?

A: No. Several studies suggest that no such risk exists.