SURGICAL APPROACHES TO THE SPINE

VIII – THE SPINE > Principles and Anatomy > CHAPTER 138 –

SURGICAL APPROACHES TO THE SPINE

patients, were severely limited in the options available to them for

surgical treatment. The source of this limitation was a combination of

technology and the experience in surgical approaches. Very few spinal

surgeons had the ability to approach every aspect of the spine with the

optimal exposure. Spinal access surgeons were few and far between. The

microscopic and endoscopic approaches that protect normal tissue and

speed recovery were scarcely available to unavailable. The evolution of

spinal surgery now allows the surgeon to approach their pathology so as

to optimize the resection of a pathologic lesion and reconstruct the

spine to optimal biomechanical advantage. Perfecting the approach is

the first step to perfecting the surgery and a major step in protecting

the patient.

-

For the posterior cervical exposure of

any level, position the patient’s head in the self-retaining

neurosurgical head fixation device that is attached to the surgical

table. Attach the drapes to the patient’s neck with stay sutures. Neck

flexion will increase exposure, but flexion is limited by the type of

pathologic process present, usually to a neutral, slightly flexed

position. In the presence of spinal instability, confirm the position

of the spine with radiographs. -

Incise the skin and subcutaneous tissue

in the midline to the fascia, and obtain hemostasis with rapid

application of hemostats and electrocautery. Insert self-retaining

retractors. -

Deepen the incision with the cautery

knife, staying within the thin white median raphe; avoid cutting muscle

tissue. The medial raphe of the cervical spine is a

P.3634

tortuous

structure that does not follow a straight path. Open the median raphe

to the spinous processes of C-2 and C-3, the occiput, or any level

needed. In children, expose no spinal levels unnecessarily to avoid

spontaneous fusion at adjacent levels, including the occiput. -

With a #15 blade or cutting cautery,

expose the bulbous bifid tips of the spinous processes. The ligamentous

attachments to C-2 are very prominent. The large spinous process of C-7

and T-1 can be identified. Identify any spina bifida of the cervical

spine on preoperative radiographs and be aware of these areas at

surgery. Insert the Cobb elevator, first facing up to elevate the tip

of the spinous process subperiosteally, then facing down to complete

the subperiosteal elevation from medial to lateral for a width of

approximately 1 inch (2.5 cm) at each level. At levels below C-2,

identify the medial edge of the facet joint at the base of the lamina

and pack each level as it is exposed. When necessary, expose the

occiput with elevators. Insert the self-retaining retractors to expose

the base of the skull and the dorsal spine of C-2. The area in between

will contain the ring of C-1. This is often very deep compared with the

spinous process of C-2. -

Maintaining firm lateral retraction of

the wound, identify the posterior tubercle of C-1 longitudinally in the

midline by probing with a sharp Cobb elevator. Begin the subperiosteal

dissection to expose the bone. -

Often the C-1 ring is very thin, and

direct pressure can fracture it or cause the instrument to slip off the

ring and penetrate the atlantooccipital membrane. Elevation on this

ring can be very dangerous if there is subluxation with constriction of

the posterior dura under this ring. The dura may be vulnerable on both

the superior and inferior edges of the ring of C-1. -

At the level of C-1, dissect laterally

only approximately 1.5 cm. The second cervical ganglion is an important

landmark on the ring of C-1 laterally; it lies approximately 1.5 cm

laterally on the lamina of C-1 in the area of the groove for the

vertebral artery. Carefully identify the most medial aspect of the

groove for the vertebral artery and vein on the superior border of the

C-1 ring. The bluish color of the vein is visualized first. By seeing

the initial ridge or the vein, damage to the artery can be avoided.

There is seldom any indication for dissection lateral to the groove of

the vertebral artery on C-1. The vertebral artery and vein are

vulnerable in the groove; in addition, as the artery passes from the

foramen transversarium of C-2 to that of C-1, it is in close proximity

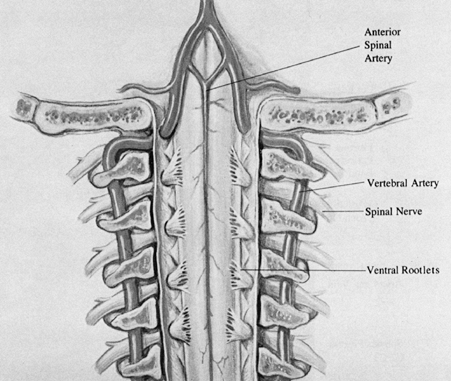

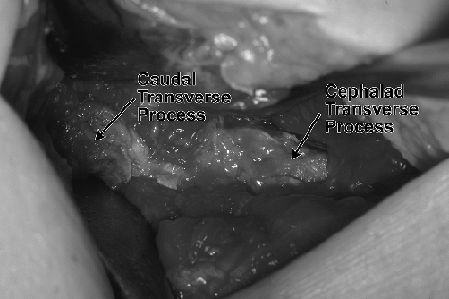

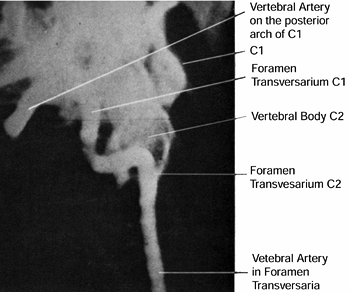

laterally and posteriorly to the joint (29) (Fig. 138.1 and Fig. 138.2). Figure 138.1.

Figure 138.1.

The course of the vertebral artery is from the foramen transversarium

of C-1 posteriorly in the region of the C1–C2 articulation through the

transversarium of C-1, then posteromedially to the posterior rim of C-1.![]() Figure 138.2.

Figure 138.2.

The anterior view without vertebral bodies emphasizes the formation of

the anterior spinal artery. There are numerous variations in this

formation, ranging from a unilateral vertebral artery contribution to

no contribution. -

The vertebral artery enters the foramen

transversarium at the sixth vertebra and progresses cephalad. It exits

through the foramen transversarium of C-1 and progresses posteriorly as

well as medially in the groove of the superior border of C-1 toward the

midline, then turns cephalad along the spinal cord to enter the foramen

magnum. The vertebral artery can be damaged by penetrating the

atlanto-occipital membrane off the superior border of the ring of C-1

more lateral than the usually safe 1.5 cm from the midline. -

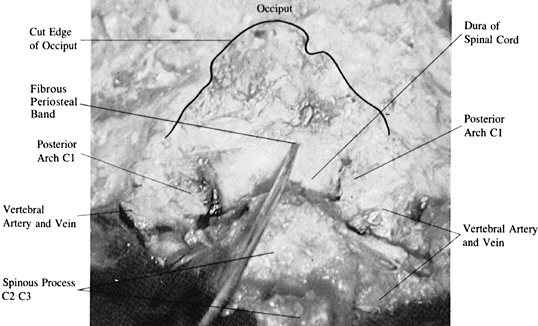

Following exposure of the ring of C-1 and

exposure to bone of the posterior occiput, different operative

procedures require exposure of the dura under the edge of the foramen

magnum (17,25,26).

Never attempt to decompress the posterior fossa under the edge of the

foramen magnum without sufficient visualization of the area cephalad to

the foramen. This is best accomplished by placing two burr holes just

off the midline of each side of the skull (Fig. 138.3).

The caudal extent of the holes is usually determined by the angle of

the drill on the skull as limited by the patient’s shoulders. Figure 138.3. Posterior approach to the foramen magnum.

Figure 138.3. Posterior approach to the foramen magnum. -

In the posterior approach to the foramen

magnum, first place burr holes in the occiput above the foramen magnum.

Two parasagittal holes allow removal of bone from the dura with a

Harrison-type rongeur. Careful dissection medially from the burr holes

provides protection from the often significant fragile venous sinus,

and dissection caudally approaches the foramen magnum. After removal of

the occiput including the bony rim of the foramen magnum, which is a

sharp-lipped structure projecting directly anterior in the transverse

plane, the fibrous attachment of the inner periosteum of the skull to

the dura at the rim of the foramen magnum is encountered. When a

transverse venous sinus in this area

P.3635P.3636

is

torn, bleeding can be significant. Attachment to the dura in this area

produces a dural leak unless the area is carefully dissected. -

Penetrate to the inner periosteum and the

bone edge with a small dissector. Expand the hole caudally to the

foramen with rongeurs. The edge itself curves under and projects

anteriorly. The periosteum of the skull at this point is often

conjoined with the dura of the spinal cord. There is a median venous

sinus in the midline, and the fascial attachment of the periosteum of

the skull to the dura often contains a transverse sinus as well. -

Passing instruments under the edge of the

foramen can produce dangerous bleeding in the posterior fossa with no

means of control. Therefore, resect the bone down to this edge from

above. -

For a more lateral approach to the C1–C2

facet joint, the vertebral artery between C-1 and C-2 must be

identified. In rotatory dislocations of C1–C2, the artery is stretched

tightly across the joint on the side that C-1 is anterior to C-2, and

it is easily damaged (29). -

For nerve root exposure below C-2,

identify the junction of the lamina and the inferior facet. Then

identify the junction of the interlaminar area and the facet joint.

Expanding these areas with a burr or a micro-Kerrison rongeur allows

entry into the intervertebral foramen and exposure of the nerve root.

Use standard prophylactic antibiotics because no special antibiotic

coverage for normal oral flora is needed. I do not use preoperative

antiseptic gargles or tetracycline (7).

-

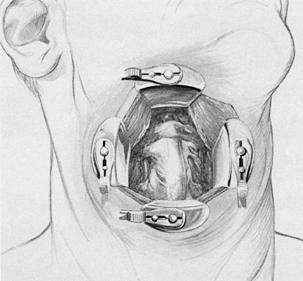

Position the patient supine with the head

slightly flexed on occipital pads, or put the head into a halo. A more

upright position can be used with certain precautions. -

The Boyle-Davis or McIver ear, nose, and

throat (ENT) retractor allows depression of the tongue and

self-retaining retraction of the mouth. The lips and teeth should be

adequately padded. -

Incise the soft palate with a curvilinear

incision around the uvula, and retract the cut edges with stay sutures

to the lateral walls of the oropharynx or to an especially bent,

blunt-tipped Gelpi retractor (7,14). Prep the oropharynx with povidone-iodine (Betadine) solution and reculture it. -

Enhanced hemostasis by injecting the posterior pharyngeal tissue with a solution of 5% lidocaine and 1:500,000 epinephrine.

-

After palpation and radiographic

confirmation of the ring of C-1, make a vertical incision from

approximately 1 cm cephalad to the tip of the odontoid to 2 cm distal

to the anterior tubercle of C-1. Incise the four layers (posterior

pharyngeal mucosa, superior constrictor muscle of the pharynx, the

prevertebral fascia, and the anterior longitudinal ligaments) directly

to the bone. -

Bluntly dissect the soft tissue off the body of C-2 below the odontoid and off the anterior tubercle of C-1.

-

Caution: The longus

colli muscle inserts on the anterior tubercle of C-1, and sharp

dissection may be needed to remove it. Venous bleeding may arise from

the recesses just lateral to the base of the odontoid. -

When necessary, the lateral masses of C1–C2 can be exposed by bluntly dissecting the bone both transversely and vertically.

-

Caution: Avoid

plunging lateral to the facet joints. To avoid damage to the internal

carotid, do not pass a stay suture too deeply into the lateral

pharyngeal wall. -

Remember, this is a deep wound, requiring

long instruments with fine tips. Most operations done with this

exposure require use of the microscope for lighting and magnification. -

After the bony work is completed and good

hemostasis is obtained, close the posterior pharynx in a single layer

with interrupted absorbable sutures.

-

Position the patient supine with the

appropriate support for the cervical spine mentioned earlier. For two

levels of pathology, it is a transverse incision, one fingerbreadth

medial to the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid. Open layers in

a fashion similar to that used with the standard cervical approaches. -

For higher anterior approaches to C-1,

C-2, and C-3, identify the superior thyroid artery and vein. The

superior thyroid artery arises from the external carotid artery at

approximately the level of the hyoid bone. It crosses through the

carotid triangle, arches deep to the strap muscles, and enters the

lateral superior aspect of the thyroid gland. Retract the superior

thyroid artery and vein inferiorly. -

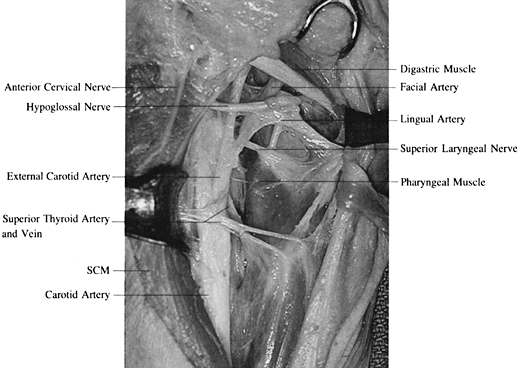

Identify and retract the hypoglossal

nerve. The hypoglossal nerve is found passing from lateral to medial

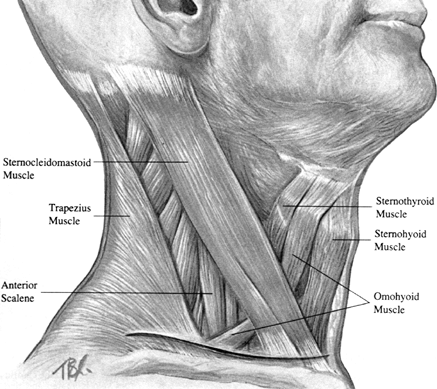

superficial to the external carotid, lingual, and facial arteries (Fig. 138.4).

It exits the skull in close proximity to the vagus nerve and courses

beneath the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein, becoming

superficial at the angle of the mandible. After the usual point of

identification of the hypoglossal nerve over the arteries, it passes

deep to the tendon of the digastric muscle and stylohyoid muscle for

distribution to the muscles

P.3637

of the tongue. Retract the hypoglossal nerve cephalad; usually, the superior thyroid artery and vein are retracted caudad.![]() Figure 138.4.

Figure 138.4.

Dissected anatomy of the carotid triangle and area just below

emphasizes the importance of identification of the hypoglossal nerve

before ligation of the arterial structures in this area. The most

common approach is cephalad to the superior thyroid artery and caudad

to the digastric muscle. SCM, sternocleidomastoid. -

Be certain of the identification of the

hypoglossal nerve before ligating any structure. It is a superficial

structure, first coursing vertically and parallel to the carotid

sheath, then horizontally, crossing medially over the carotid and its

branches. -

Identify the lingual artery, which arises

from the external carotid. From the level of the hyoid, it crosses

under the digastric and stylohyoid muscles in its ascent to the oral

pharynx. -

Identify and ligate the facial artery.

The facial artery next leaves the external carotid artery, coursing

under the ramus to the mandible within the carotid triangle. It passes

deep into the digastric muscle and enters the face at the anterior edge

of the mastoid after crossing on the submandibular gland. -

Identify the digastric muscle. This

muscle is easily retracted cephalad with the hypoglossal nerve. When

necessary, divide the stylofascial band running from the stylohyoid

process to the posterior pharynx. -

Difficulties may be encountered with the

superior laryngeal nerve, both external and internal branches, and the

pharyngeal branches of the vagus nerve. These nerves should be

identified and retracted, but they frequently suffer from the

retraction. Continue to use finger palpation to identify the spine and

the carotid artery. -

Retract the carotid sheath and the

ligated stumps of the lingual and facial arteries laterally, and

retract the musculovisceral column medially with deep right-angle,

hand-held blunt retractors. -

With a Kittner dissector, make a careful, blunt dissection at this point, to identify the prevertebral fascia.

-

Elevate the fibers of the longus colli

muscle and fascia off the vertebral body in a lateral and cephalad

direction. Insert the sharp claw blades of the Cloward retractor under

the longus colli. The smooth-tipped blades can be used if firm fixation

cannot be obtained under the longus colli (3). Deep hand-held retractors are also quite effective (Fig. 138.5). Figure 138.5. The spine is exposed with deep retractor blades.

Figure 138.5. The spine is exposed with deep retractor blades.

the fascial covering of the visceral structures of the neck (10).

This investing layer of cervical fascia is attached inferiorly to the

acromion, clavicle, and manubrium of the sternum in an outer and inner

layer superiorly to the hyoid bone, posteriorly to the mandible and

mastoid processes, and superior to the nuchal line. The interval

between the two laminae of the external investing fascia is called the

suprasternal space, or the space of Burns. This space, which contains

the anterior jugular veins and sternal head of the sternocleidomastoid,

is referred to as the cul-de-sac of Bruger. Communication between the

anterior and external jugular veins is channeled through this inner

laminar area.

sheath and joins the external investing fascia at the posterior border

of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Inferiorly, the middle cervical

fascia attaches to the posterior surface of the sternum, as do the

muscles that they cover. It is the middle cervical fascia that attaches

to the clavicle and forms the loop for the inferior belly of the

omohyoid muscle.

endothoracic fascia caudally, and laterally it covers the levator

scapulae and splenius muscles. It extends posteriorly to attach to the

spinous processes of the vertebrae. In the neck and throughout the

spinal column, it covers the longus colli and capitus muscles and is

secured to the tips of the transverse processes.

anterior tubercles of the transverse processes of C-3, C-4, C-5, and

C-6. It inserts into the scalene tubercle on the inner border of the

first rib and into the ridge on the cranial surface of the rib ventral

to the subclavian groove. The scalenus medius originates from the

posterior tubercle of the transverse processes of the last six cervical

vertebrae and inserts into the first rib.

Sibson’s fascia. These fascial connections and the scalenus minimus

connect the transverse processes of the seventh cervical vertebra to

the first rib. Sibson’s fascia, as a portion of the prevertebral

fascia, becomes continuous with the endothoracic fascia on the inner

surface of the first rib. Extending medially between the anterior

scalene muscle and the spine is the all-important retropharyngeal

fascial cleft. This is the space beneath the visceral structures,

superficial to the prevertebral fascia; it is in this space that

retraction and work on the anterior portion of the spine takes place.

-

Position Gardner-Wells tongs or

headhalter traction for cervical traction. Position the head in slight

extension and rotation to the right. Contour a small, curved sand bag

under the neck to support the spine. Drape off the entire neck with

adhesive towel drapes. Select the level of the skin incision.

Superficial landmarks are used to determine the appropriate placement

of the skin incision over the appropriate level of the spine. For

approaches to C-1, C-2, and C-3, start the incision midline extended to

the lateral border of the carotid sheath, one fingerbreadth below the

angle of the madible. For approaches to C2–C3 start the incision at the

midline and extend it to the lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid

at the level of the cephalad margin of the thyroid cartilage. For

C4–C5, start the incision at the midline and extend it to the medial

border of the sternocleidomastoid at the level half way between the

cricoid cartilage and the superior border of the tyroid cartilage. For

C5–C6, start the incision at the midline on the cephalad margin of the

cricoid cartilage and extend it to the medial border of the

sternocleidomastoid. For C6–C7, start the incision at the midline of

the caudal margin of the cricoid cartilage and extend it to the medial

border of the sternocleidomastoid. For C7–T1, start the incision at the

midline; extend it just lateral of the medial border of the

sternocleidomastoid, halfway between the cricoid cartilage and the

clavicle. We prefer the midline starting point, because retraction of

the medial muscular visceral column is the strongest structure

requiring retraction. Having the skin open to the midline eases that

retraction. The self-retaining retractor is

P.3639

placed in the midline. Having the skin open to the midline aids in that retraction. -

After making a transverse skin incision at the appropriate level (Fig. 138.6),

dissect through the subcutaneous tissue to the platysma muscle. Elevate

the platysma muscle with Adson forceps, and open it carefully, in the

line of the fibers, when possible. Beware of damage to veins and the

sternocleidomastoid muscle (2,21). Insert a spring retractor.![]() Figure 138.6.

Figure 138.6.

The more cosmetically suitable transverse incision is made at the

appropriate level and should allow exposure of up to two discs and

three vertebrae. A vertical incision can be used for an even greater

exposure. -

Open the superficial cervical fascia and identify the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (25).

The first key to successful exposure is adequate identification of the

medial border of the sternocleidomastoid so that it may be retracted

laterally (23) (Fig. 138.7).

With identification of this medial border, bluntly develop the interval

between the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the sternohyoid muscles.

Retract the posterior cutaneous nerves. Bluntly dissect the soft tissue

and spread it vertically in this interval. Figure 138.7.

Figure 138.7.

The key to the dissection at this point is to identify the medial

border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. With lateral retraction of

the sternocleidomastoid, the interval between this muscle and the

medial strap msucles is delineated. -

Retract the sternocleidomastoid laterally

and the strap musculature medially with angled retractors. Identify the

middle cervical fascia. The omohyoid muscle crosses from proximal

medial to lateral distal through the middle cervical fascia at C6–C7.

Retract the omohyoid; when necessary, divide it and later repair it in

its midportion. -

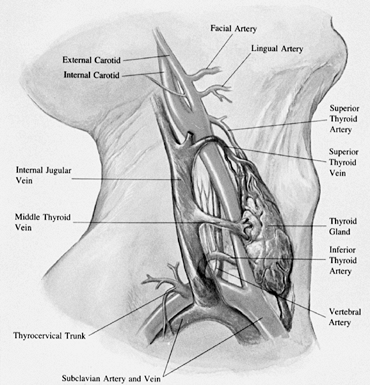

After retracting the sternocleidomastoid

muscle laterally and the strap musculature medially, identify the

arteriovenous structures of the middle cervical fascial layer (Fig. 138.8).

Palpate the carotid pulse. Open the midline cervical fascia medial to

the carotid artery. Ligate and tie the medial thyroid vein. Retract

cephalad the superior thyroid artery and retract caudad the inferior

thyroid artery to expose the midcervical spine.![]() Figure 138.8. Arteriovenous structures of the middle cervical fascial layer.

Figure 138.8. Arteriovenous structures of the middle cervical fascial layer. -

Spread the middle cervical fascia just medial to the carotid sheath (23), with finger dissection spreading vertically and horizontally (3).

Identify the inconstant middle thyroid vein crossing at approximately

C-5, and ligate and divide it when needed. Identify the spine with

finger palpation of the anterior surface of the vertebral body. Insert

a blunt, nonlipped Cloward hand-held retractor into the wound directly

down to the spine. Hold the retractor on the right longus colli. Beware

of entering the tracheoesophageal groove (and thereby damaging the

recurrent laryngeal nerve with the retractor tip) (19). -

Distally retract the inferior thyroid

artery and vein at the C6–C7 level, and proximally retract the superior

thyroid artery and vein with the superior laryngeal nerve at C3–C4. -

Do not mistake the transverse process for

the anterior surface of the vertebral body because an incision deep in

this area will damage the longus colli, the sympathetic chain, and

possibly the vertebral artery. An incision into the longus colli

produces bleeding. -

Palpate a disc in the midline of the

spine and open the prevertebral fascia with a small dissector

longitudinally until the disc can be identified. If the finger dissects

directly to the spine and the retractor is then inserted, the esophagus

cannot be seen. The empty esophagus is only a soft, flat ribbon-like

structure simulating the musculature over the anterior portion of the

spine. Always use either an esophageal stethoscope or a nasotracheal

tube to identify the esophagus. -

Insert a needle into a disc for lateral radiographic confirmation of the level.

-

Retract the esophagus, trachea, and

anterior strap muscles medially and the carotid sheath and

sternocleidomastoid muscle laterally. -

Incise the prevertebral tissue in the

midline on the disc. Use a bipolar coagulator along the medial edge of

the longus colli as needed. Using sharp periosteal elevators, fashion a

flap of muscle under which the retractor can be inserted laterally from

the midline. Insert the clawed blades of the Cloward deep

self-retaining retractor under the longus colli on both sides of the

spine. To expose the desired disc, use the blunt-tipped Cloward

retractor vertically (3). -

Insert the clawed retractor first. Hold

it down on the spine while inserting the near retractor. The Cloward

curved periosteal elevator can lift up the flap for insertion of the

blade retractor. -

After hemostasis has been achieved, close

the deep wound by removing the retractors. Use subcuticular skin

closure, and always use a closed suction wound drainage system.

-

Place the patient in the supine position

with the neck slightly hyperextended and rotated away from the side of

the approach. Use an inflatable cervical pillow for support; a small

roll under the shoulder often helps to extend the neck. -

Caution: Location of

the thoracic duct and recurrent laryngeal nerve becomes even more

important at this level. Approaches from the left for C6–T2 are

directly in the vicinity of the thoracic duct. Identify the thoracic

duct when possible and protect it. A large fatty meal the day before

surgery will help. If the thoracic duct is inadvertently divided,

double ligate both ends well. The approach to the right definitely

requires identification and protection of the recurrent laryngeal

nerve. I recommend the left supraclavicular approach to avoid risk to

the recurrent laryngeal nerve. -

Make a transverse incision approximately

one fingerbreadth above the clavicle from the midline to the posterior

border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. After the skin and

subcutaneous tissue are divided and small skin self-retaining

retractors are placed, incise the playtsma muscle in the line of the

incision. As in the higher approaches, identification of the medial

border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is imperative. -

In addition, identify and define the

anterior and posterior borders of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The

external jugular vein, although somewhat variable, is usually directly

in the operative field, and the anterior jugular vein is positioned

more medially. Divide it, if necessary. -

Incise the external investing fascia.

Pass a probe or finger laterally from the medial border of the

sternocleidomastoid to clear off the venous structures underneath the

clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid. -

Divide the sternocleidomastoid laterally to medially 1 inch from its insertion, watching for the internal jugular vein (12).

If required for visualization, remove the sternal head of the

sternocleidomastoid muscle in the same fashion. Eventual reattachment

depends on suturing the fascial covering of the muscle. -

Retract the divided sternocleidomastoid

in a cephalad-caudad direction with self-retaining blunt retractors.

The floor of the incision, at this point, consists of the middle

cervical fascia, which contains the omohyoid and the sternohyoid

muscles. -

Enter the middle cervical fascia lateral

to the carotid sheath. Bluntly dissect to the surface of the anterior

scalene muscle. The superficial surfaces of the anterior scalene are

composed of the outer layer of prevertebral fascia, which is the third

and deepest of the fascial layers dealt with in this approach. Lying on

the surface of the anterior scalene muscle is the phrenic nerve. The

phrenic nerve crosses from lateral to medial, and cephalad to caudad.

Retract the phrenic nerve medially after freeing it from the surface of

the anterior scalene muscle. Identify the large internal jugular vein

medially and feel for the carotid pulse. Although retraction of the

carotid sheath is possible laterally, attempt to retract the internal

jugular vein and carotid sheath medially (24).

Retract the phrenic nerve to obtain good visualization of the anterior

scalene, which is between the phrenic nerve and the middle scalene. The

brachial plexus and suprascapular nerves are more superficial at the

lateral border of the anterior scalene. -

Delineate the medial and lateral borders

of the anterior scalene muscle. The fascia on the deep surface of the

anterior scalene is Sibson’s fascia, a continuation of the prevertebral

fascia that encloses this muscle. The apex of the parietal pleura and

lung form the undersurface of Sibson’s fascia. -

Retract the anterior scalene laterally.

Now carry out blunt dissection medially under the retracted carotid

sheath. Stay on the prevertebral fascia of the spine. -

If more exposure is needed, carefully

approach under the anterior scalene without violating the major

portions of Sibson’s fascia, and divide the anterior scalene muscle.

The scalene can be retracted cephalad to caudad with self-retaining

blunt retractors. Sibson’s fascia now makes up the floor of the wound;

the large internal jugular vein and the carotid sheath are located

medially; the apex of the lung is beneath Sibson’s fascia in the floor

of the wound; and laterally, the brachial plexus courses superficial to

the scalenus medius. The proximal portion of the anterior scalenus

muscle may be dissected from the anterior tubercle of the transverse

processes to allow greater exposure of the spine or brachial plexus (22). -

Incise Sibson’s fascia at the transverse

processes and bluntly retract it inferiorly. This retracts the pleura

of the lung, which is usually at the T-1 level. Mobilize the recurrent

laryngeal nerve medially with the carotid sheath and medial visceral

column. Expose the spine by opening the fascia in the midline over the

body. The transverse processes and rib heads can be exposed (18). -

Dissect to the second and third rib

heads. This produces a rather lateral exposure of the spine. From the

rib heads, dissect medially to enter the retropharyngeal fascial cleft

on the anterior surface of the spine without having to dissect the

longus colli muscle. Identify the vertebral artery entering the spine

at C-6. The subclavian vein courses on the floor of the wound. -

If the approach is done from the left,

the junction of the internal jugular veins and the subclavian veins

will contain the thoracic duct. Identify the thoracic duct. In case of

damage, double ligate it proximally and distally. Chylothorax can be

prevented with proper ligation.

P.3642

Often,

a more judicious approach involves blunt dissection, progressing

cephalad to caudad, as has been described for the transverse processes

of C-5, C-6, and C-7, to the rib head of the first rib down on the

spine. This will sweep most of these structures cephalad to caudad. The

danger, of course, lies in cutting restraining structures that cross

the field. The sympathetic chain (stellate ganglion at C-7) lies on the

rib heads in a lateral position. Avoid damage by dissecting more

medially.

approach to the T1–T4 area. Resection of the third rib allows greater

spreading of the intercostal area than does second rib resection (13).

The cephalad extension of the exposure is enhanced with kyphosis

deformity of the cervicothoracic junction area. The second rib can be

removed if the operative exposure is inadequate.

-

Place the patient in the lateral

decubitus position, with the left side up. Prep and drape the entire

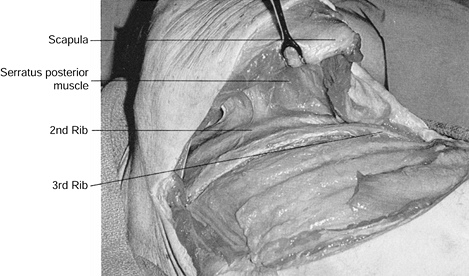

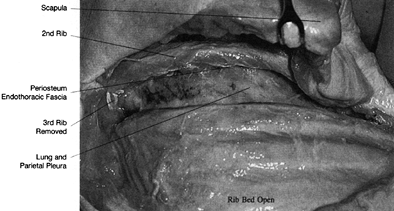

left upper extremity in a sterile manner (Fig. 138.9). Figure 138.9. Skin incision for third rib resection for the transthoracic approach.

Figure 138.9. Skin incision for third rib resection for the transthoracic approach. -

Incise the skin and subcutaneous tissue

from the lateral paraspinous area at T-2, along the medial caudal

border of the scapula, under the axilla to the costal cartilage of the

third rib. -

Carefully divide each subsequent muscle

layer down to the level of the rib, sectioning portions of the

trapezius, latissimus dorsi, rhomboid major, and serratus posterior as

needed. Careful dissection with electrocautery and meticulous

cauterization of each muscle bleeding point allows exposure to the

outer periosteum of the third rib with a minimal amount of bleeding. As

the muscle layers are divided, retract the scapula cephalad and

medially to tense the muscle tissue for easier cutting. Palpate the

chest wall cephalad for identification of the third rib. Remember that

the first rib is situated inside the second; this is important for

reaching the correct rib level (Fig. 138.10).![]() Figure 138.10. Elevation of the scapula aids in the division of the muscles attached to the scapula and allows visualization of the third rib.

Figure 138.10. Elevation of the scapula aids in the division of the muscles attached to the scapula and allows visualization of the third rib. -

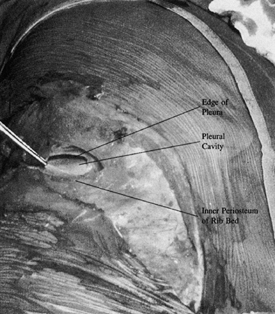

Dissect the external periosteum off the third rib with periosteal elevators. Excise the third rib from the angle

P.3643

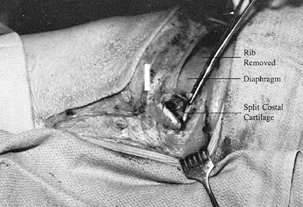

of the rib to the costal cartilage. Open the rib bed as in the standard thoracotomy approach (Fig. 138.11).

The rib bed consists of periosteum, endothoracic fascia, and parietal

pleura. Incise the parietal pleura, carefully avoiding damage to the

underlying lung. Pick up the inner periosteum of the rib bed with Adson

forceps and open the rib bed with scissor tips or fine dissection with

a knife blade. To avoid lung and pleural adhesions just under the rib,

complete the opening of the rib bed with semiclosed scissors, using a

finger to clear lung from the undersurface. Figure 138.11. Excise the third rib from the angle of the rib to the costal cartilage.

Figure 138.11. Excise the third rib from the angle of the rib to the costal cartilage. -

Use the Feochetti rib spreader to open the intercostal area. Deflate or retract the lung with a spatula-type retractor (Fig. 138.12).

![]() Figure 138.12. With the rib bed open, place the Feochetti rib-separating retractor and retract the lung with a spatula lung retractor.

Figure 138.12. With the rib bed open, place the Feochetti rib-separating retractor and retract the lung with a spatula lung retractor. -

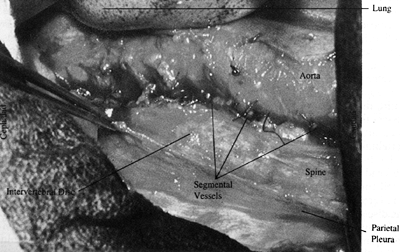

Identify the aorta, spine, ribs, parietal

pleura, and veins under the parietal pleura in the wound. The highest

intercostal vein is usually seen. -

Use an Adson forceps and Metzenbaum scissors to open the parietal pleura delicately over the costovertebral articulations.

-

Identify the prominent soft or white

tissue of the intervertebral disc. This is a relatively avascular,

safer plane for dissection than the surface of the vertebral body. Make

an intraoperative radiograph to verify the level. -

Dissect each intercostal vessel, tying

and ligating it over the vertebral body. Bluntly dissect the soft

tissue from the vertebral body (Fig. 138.13). Figure 138.13.

Figure 138.13.

After the parietal pleura is opened, bluntly dissect its edges off the

spine with a “peanut” or sponge. The parietal pleura may be sutured

back laterally with stay sutures when necessary for continued

retraction. -

Fully expand the lung and visualize in

all areas before closure. Close the parietal pleura over the spine

whenever possible. Place the chest tube through a separate aperture,

preferably in the ninth intercostal space. Protect the lung during

closure. Close the chest with the rib approximator. Close the rib bed

with interrupted permanent braided Dacron sutures. The chest tube can

usually be removed within 48 to 72 hours, depending on drainage and

expansion of the lung.

exposure of vertebral levels T-2 to L-2. Rib selection depends on the

location and extent of the pathologic process. Anatomic variations at

the cervicothoracic and thoracolumbar junction dictate the rib to be

taken. Choose the rib to be resected for a certain vertebral level by

one of two methods:

-

When the pathology dictates a direct

anterior approach to the vertebral column (e.g., kyphotic tuberculous

abscess), choose the rib directly horizontal to the vertebral level at

the midaxillary line in an anteroposterior chest radiograph. The rib

removed must be cephalad to the lesion to give adequate proximal

exposure of the lesion (13). -

When direct access to the spinal canal is

needed at one disc (e.g., ninth rib to the T8–T9 disc), use a left

approach because it is much easier to deal with the aorta and the

segmental vessels from the left side. For patients with a large abscess

in the right chest or in other circumstances that dictate a right

thoracic approach, be prepared to mobilize the vena cava and associated

veins from that side.-

Place the patient on the bean bag. Use a

double-branched endotracheal tube into the right and left mainstem

bronchi to allow selective collapse of the left lung. Center the

midthorax of the patient over the break in the table. Pad the dependent

axilla, and pad and protect the left arm. Stabilize the pelvis with a

strap to the table. Place a pillow between the legs, and pad all the

bony prominences. Flex the table to allow better exposure. -

Open the skin and subcutaneous tissue

from the lateral border of the paraspinous musculature to the

sternocostal junction over the rib to be resected. Inject the incision

with 1:500,000 epinephrine. Place the thoracotomy incision slightly

tangential to the rib to be resected, allowing easier resection of more

than one rib if necessary. -

After inserting the self-retaining

retractors, extend the wound with the electrocautery down through the

muscle layers to the thorax. When necessary for full exposure, the

latissimus dorsi, trapezius, and rhomboid major and minor muscles can

be sectioned. -

After the chest wall is exposed, count

the ribs from the twelfth up to the appropriate rib or from the first

rib downward. The first rib appears to be inside the second when one is

palpating from this angle, and it is often difficult to find. Each rib

articulates with the superior portion of the body in the area of the

disc space of the level above. Therefore, the twelfth rib inserts

closer to the T11–T12 intervertebral disc space. Confirm identification

of the rib with a radiograph. -

Expose the outer periosteum of the rib

with the electrocautery and cut directly to the bone through the

periosteum from the angle of the rib to the costal cartilage. Elevate

the periosteum off the outer rib surface. Use the curved-tip rib

elevator to strip the superior and inferior borders of the rib,

maintaining an intact elevated periosteum. Elevate the inner periosteum

of the undersurface of the rib with the Doyen elevator. -

Caution: Avoid

damaging the intercostal vessels that course on the inferior surface of

the rib. Elevate the periosteum of the rib by cutting with the elevator

directly on bone. Avoid plunges that might inadvertently enter the

pleura. -

With the intact periosteum freed from the

rib, cut the rib with the rib cutter as far posteriorly as necessary

between the costotransverse joint and the angle of the rib and

anteriorly at the costal junction. Remove the rib and save it for bone

graft. Lightly wax the bone on the end of the rib after rasping to make

sure there are no ragged edges. Tie a sponge on the tip of the stump to

protect the surgeon during the procedure. -

Pick up the inner periosteum of the rib

bed with Adson forceps and open the rib bed with scissor tips. Avoid

lung and pleural adhesions. Complete the opening of the rib bed with a

semiclosed scissors after using a finger to clear lung from the

undersurface. When pleural adhesions exist, first attempt to dissect

the adhesions bluntly with the finger or sponge stick. If necessary,

sharply dissect dense adhesions and ligate vascular structures. -

Retract the lung medially with a spatula

lung retractor or deflate it. Retraction of the lung should be removed

at least every 20 minutes to allow adequate expansion of the lung and

to prevent postoperative atelectasis. Insert the Feochetti separator in

the rib resection defect, with moist lap sponges over the edges. Expand

the Feochetti separator to allow adequate visualization inside the

thoracic cavity. Flexion of the table may be of benefit. -

The anatomy of the spine at this point is

obscured by the reflection of the parietal pleura as it covers the

soft-tissue structures over the spinal column. Elevate the parietal

pleura with Adson forceps and open it with Metzenbaum scissors. Extend

the opening of the parietal pleura cephalad and caudad on the spine by

cutting over a peon dissected under the pleura. The presence of a large

paravertebral abscess at this point means only that the abscess should

be exposed just as the spine would be. When an abscess is present, cut

its outer wall longitudinally and approach the spine through the

abscess. -

The disc is the more prominent, softer,

white structure of the spine. The discs are relatively avascular and a

much safer area for dissection. An intercostal vein and artery cross

the midportion of each vertebral body. -

Bluntly dissect the edges of the parietal

pleura off the spine with a Kittner dissector or sponge. Elevate the

pleura on the discs and lift it off the vessels on the vertebral body.

Dissection begun over the disc is less likely to cause bleeding. Make a

radiograph at this point to verify the level. After the parietal pleura

is opened, it may be sutured back on itself laterally with two stay

sutures. -

Separate, sever, and ligate each of the

intercostal vessels over the vertebral body. If a large paravertebral

abscess is present, the arteries enter the abscess. Take care to avoid

clamping segmental arteries too close to the aorta so as to lose the

tie or too close to the intervertebral foramen. Tie arteries and veins

separately or together, depending on their size. Pass a right-angled

clamp under the vessels, and use a braided 2-0 suture in a free tie to

tie off first the medial and then the lateral exposed vessels; use

vascular clamps in a similar fashion. -

Caution: Take care

to dissect adequately under the vessels. A common mistake is to have

both ligature sutures in the same place under the vessel and not have

adequate room for cutting between them. Handle every segmental vessel

in the area of where bony work will be done in this manner. Paralysis

due to ligation of a segmental artery on the vertebral body has not

been a problem (13). -

Caution: Do not dissect into the intervertebral foramen.

-

Bluntly expose the outer surface of the

spine after division of the segmental vessels. When bone and disc

exposure is needed, cut with the cautery directly to bone. Use the

periosteal elevator to dissect the annulus off the disc and the

periosteum off the bone medially and laterally, exposing the entire

disc and vertebral column. The tendency is not to dissect the soft

tissue laterally enough off the spine. The rib head articulates with

the cephalad half of its appropriate vertebral body and the disc space

above. Access to the posterior disc and spinal column can be gained by

resecting the rib head (Fig. 138.14). Removal

of the head of the rib and its articulation allows excellent exposure

of the posterolateral aspect of the intervertebral disc. After the rib

head and disc are removed, identify the intercostal nerve, dural sac,

posterior vertebral body wall, and spinal canal. The costal vertebral

articulation is a major stabilizing structure in the thoracic spine.

Identifying the left pedicle in a left-sided approach helps locate the

spinal canal for orientation. The vertebral body can be completely

exposed by resecting the disc above and below to identify the posterior

body wall and spinal canal and dissected laterally to identify the

pedicle and spinal canal.![]() Figure 138.14.

Figure 138.14.

The rib articulates with the cephalad half of its appropriate numbered

vertebral body and with the disc space above. Therefore, the tenth rib

articulates at T9–T10. -

Visualize the lung fully expanded in all

areas before closure. Close the parietal pleura over the spine whenever

possible. Place the chest tube through a separate aperture, preferably

in the ninth intercostal space. Protect the lung during closure. Close

the chest with the rib approximator. Close the rib bed with interrupted

P.3646

permanent

braided Dacron sutures. The chest tube connects to the water seal. With

the lung re-expanded, the chest tube can usually be removed within 48

to 72 hours, depending on drainage and expansion of the lung.

P.3645 -

thoracolumbar junction are much the same as in the rest of the thoracic

spine. Hodgson and Rau (13,14) recommend a ninth rib resection for T10–L1. Dwyer et al. (6)

recommend a tenth rib resection with the standard thoracolumbar

approach for the T10–L1 area. For exposure of the T12–L1 area, Perry (19)

recommends a tenth rib resection. Ideally, choosing the rib in the

midaxillary line opposite the lesion or the apex of a curve allows

adequate proximal exposure for working “down” or caudad on the lesion.

for maximum exposure of T11–T12. A tenth rib thoracoabdominal approach

is preferred for exposure of the T12–L1 area. Both techniques involve

detaching the diaphragm at its circumference. A twelfth rib approach is

used in cases in which less exposure is needed or when it is imperative

that the diaphragm not be taken down. A twelfth rib extrapleural

retroperitoneal approach is recommended for exposure of L1–L2.

approach with less expansive exposure, is the highest practical,

extrapleural, retroperitoneal anterior approach for the exposure of the

T10–L2 area. It is ideally used in severely ill patients in whom

avoiding opening the pleural cavity and cutting the diaphragm is an

advantage. Another alternative for limited extrapleural exposure with

low morbidity is the posterior costotransversectomy approach. The

vertebral body and spinal canal can be exposed by following the twelfth

subcostal nerve to T12–L1. Unless at least two levels are exposed with

the approach, the visualization necessary to perform total discectomy,

vertebrectomy, and strut grafting is extremely poor compared with the

anterior approach.

is the tenth rib thoracolumbar approach for long exposures of the

thoracic and lumbar spine. This approach allows proximal and distal

extension for multilevel operations and optimum exposure for bony work.

-

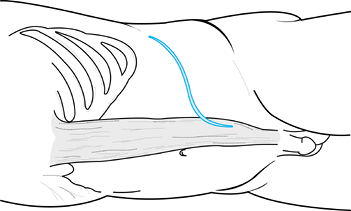

Place the patient in the lateral

decubitus position. Make the approach from the convexity of the

scoliosis or from the left side, when possible (Fig. 138.15).

A left-sided approach is preferred because of ease of mobilization of

the aorta compared with the vena cava and because splenic retraction is

easier than hepatic reconstruction. Open the skin and subcutaneous

tissue from the lateral

P.3647

border of the paraspinous musculature over the tenth rib to the junction of the tenth rib and costal cartilage (20).

Curve the incision anteriorly from the tip of the tenth rib to the

lateral rectus sheath and distally down the edge of the sheath as far

as necessary for exposure. Use electrocautery to slowly extend the

incision through each muscle layer while an assistant aggressively

picks up bleeders with two Adson forceps. Figure 138.15. Skin incision for a tenth rib thoracoabdominal approach.

Figure 138.15. Skin incision for a tenth rib thoracoabdominal approach. -

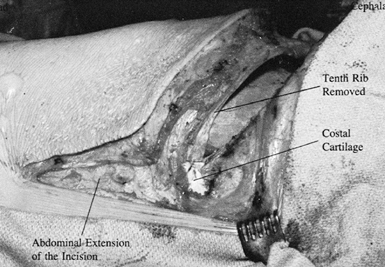

Open the superficial periosteum of the

tenth rib to the costal cartilage. Use the sharp, curved periosteal

elevator to remove the superficial and deep periosteum off the rib.

Take care to avoid the neurovascular bundle on the inferior surface of

the rib. Cut posteriorly at the angle of the rib, and cut at the

junction of the rib and costal cartilage. Remove the rib. On opening

the pleural space, retract the lung and fully open the rib bed with

scissors (Fig. 138.16). At this point, the intrapleural cavity is opened and the retroperitoneal cavity is still closed.![]() Figure 138.16. With the rib removed, carefully delineate the costal cartilage.

Figure 138.16. With the rib removed, carefully delineate the costal cartilage. -

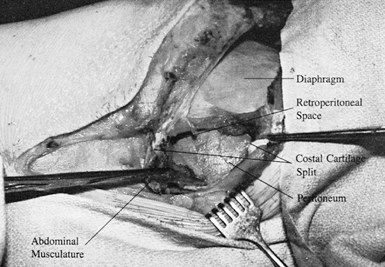

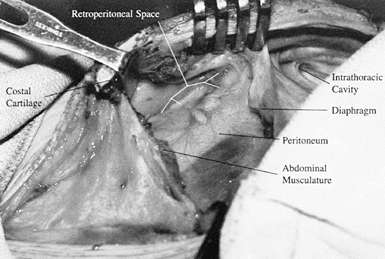

Split the costal cartilage with a knife

along its length. Open the undersurface of the costal cartilage and

retract the two tags of cartilage (5,6,20) (Fig. 138.17). Figure 138.17.

Figure 138.17.

Split the costal cartilage. Open the most superficial layer of soft

tissue under the costal cartilage enough to allow retraction of the

cartilage tips. -

Identify the peritoneum and

retroperitoneal space by blunt dissection under the retracted split

tips of the costal cartilage. The guide to the retroperitoneal space is

the light areolar tissue of the retroperitoneal fat (Fig. 138.18).![]() Figure 138.18.

Figure 138.18.

Retract the split tips of costal cartilage. Identify the insertion of

the diaphragm into the cephalad cartilage tip and the insertion of the

abdominal musculature into the caudad cartilage tip. -

Bluntly dissect the peritoneum off the inferior surface of the diaphragm (Fig. 138.19).

The peritoneum is swept, using a sponge, first from the undersurface of

the diaphragm, then from the transversalis fascia, and finally from the

abdominal wall. Figure 138.19. Bluntly dissect the periosteum off the inferior surface of the diaphragm.

Figure 138.19. Bluntly dissect the periosteum off the inferior surface of the diaphragm. -

After the peritoneum is retracted,

carefully open the abdominal musculature (the external oblique, the

internal oblique, and the transversus abdominis) one layer at a time,

with complete hemostasis. At this point the chest and retroperitoneal

space are open and the diaphragm is the intervening structure in the

wound. -

Incise the diaphragm from inside the

chest with clear visualization under the diaphragm in the

retroperitoneal space. Extend the incision in the diaphragm

circumferentially, 1 inch from its peripheral attachment to the chest

wall (28). Use marker clips throughout the take-down of the diaphragm to allow accurate reapproximation. -

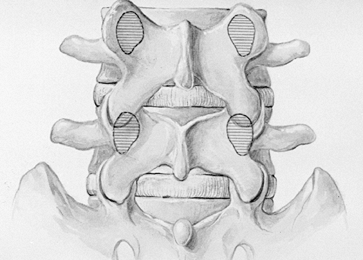

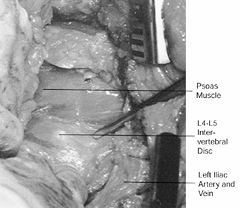

For work on T2–L1, resect the diaphragm

to the spine. Cut the crus of the diaphragm and elevate it off the

spinal column. Use protected Deaver retractors to retract the

peritoneal sac anteriorly. Identify the psoas muscle with its most

cephalad attachment to the transverse process of L, and protect the

muscle because the lumbosacra plexus is under it. With a large rib

retractor, such as the Feochetti, open the tenth rib incision in the

chest. The spine will be visualized from approximately T-6 as far

distally in the lumbar spine as necessary. In the lumbar spine, remove

the crus of the diaphragm and the attachments of the psoas muscle, if

needed, for proper visualization of the spine. In the thoracic spine,

the parietal pleura is opened as in a standard thoracotomy approach.

Tie and ligate the intercostal artery and vein to allow mobilization of

the major vascular trunks. If it is identified as in the operative

area, the thoracic duct, which usually crosses right to left around

T4–T5, is tied off. Avoid the sympathetic plexus. After the intercostal

vessels are removed, cut directly to the spine. Dissection is carried

out on the spine, and soft tissue is removed laterally. -

The key to closure is the reapproximation

of the costal cartilage. After the diaphragm is resutured with multiple

interrupted sutures and the split cartilage is reapproximated, insert

the chest tube in the eighth intercostal

P.3649

space

and pass it posterosuperiorly. Attached to the cephalad half of the

costal cartilage is the insertion of the diaphragm and the

interthoracic fascia. Inserting into the distal split of costal

cartilage is the transverse abdominal fascia and attachment for the

abdominal musculature. With the costal cartilage reapproximated, the

layers of the abdominal musculature are better defined. Close each

layer of the abdominal wall separately when possible, and close the

chest as in a standard thoracotomy.

-

Position the patient supine on the table with the lower lumbar spine at the level of the kidney rests.

-

Make a lower abdominal pararectus

incision through the skin and subcutaneous tissue. The most immediate

layers are those of the external oblique with its transition into the

linea semilunaris, which leads to the fascia of the rectus sheath. The

linea semilunaris is composed of the aponeurosis of the three layers of

the abdominal musculature and their fascia. -

Incise the fibers of the external

oblique, the internal oblique, and the small thin layer of transversus

abdominis muscles laterally to the semilunaris in line with the skin

incision. -

Identify the transversalis fascia, which

is the internal investing fascial layer of the abdominal cavity.

Dissect the outer surface of the transversalis fascia to the edge of

the rectus sheath. The transversalis fascia splits at this point to

form the lamina of the rectus sheath. The posterior lamina of the

rectus sheath forms the endoabdominal fascia in this area. -

Carefully incise the transversalis fascia laterally to the linea semilunaris, and identify the peritoneum through the incision.

-

Begin the incision in line with the skin

incision. Dissect the peritoneum with a sponge or gloved hand off the

undersurface of the transversalis fascia. Open the abdominal wall after

the peritoneum has been identified and cleared. -

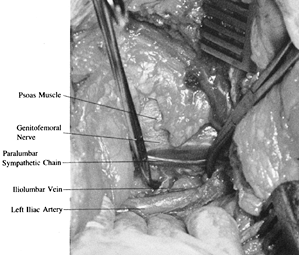

Bluntly dissect the peritoneum from the

lateral abdominal wall, progressing posteriorly. Identify the psoas

muscle, as in any retroperitoneal approach to the spine. Retract the

peritoneum off the left iliac artery and vein by use of the surgeon’s

hand, a padded deaver retractor, or sponge sticks. Sweep the peritoneum

with the ureter from left to right, and expose the left common iliac

artery and vein. Insert Freebody pins or special retractors. -

Palpate and identify the intervertebral

disc. Remember that this is a relatively avascular area. With any

approach to the L4–S1 area, identify the left iliolumbar vein and

ligate it when necessary. Dissection within the bifurcation of the

aorta should be blunt and as avascular as possible. Remember, the left

common iliac vein lies in the bifurcation over the L4–S1 disc. The

variation in inferior vena cava and lumbar veins often dictates the

exact approach from this point. -

Bluntly retract and protect the hypogastric plexus.

-

Allowing the peritoneal sac to fall into

place, close the muscle layers with a running suture. The transversus

abdominis and the internal oblique may be closed together.

anterior pararectus vertical incision, a J-shaped renal incision, or a

horizontal lateral abdominal incision can be used (Fig. 138.20). I prefer the horizontal oblique incision.

|

|

Figure 138.20.

For retroperitoneal exposure of the lumbar spine, an anterior pararectus vertical incision, a J-shaped renal incision, or a horizontal lateral abdominal incision can be used. |

-

Place the patient in the supine position

over the kidney rests. For patients with a large abdominal pannus, the

left lateral decubitus position can be used. In the lateral position,

too much hip flexion at this point will limit the operative exposure

anteriorly. -

Start the incision equidistant between

the lowest rib and the superior iliac crest in the midaxillary line,

and extend it approximately to the edge of the rectus sheath. The level

of the incision varies according to the level of the spine approached:

L5–S1 is in the lower half of the distance between umbilicus and

symphysis, L4–5 is in the upper half, L3–4 is at the umbilicus, and

L2–3 is above the umbilicus. The length of the incision can vary

according to the surgeon’s experience, the exposure needed, and the

operation to be done. -

Muscle relaxation allows greater mobility to the abdominal

P.3650

wall and decreases the contractility of the muscle as it is incised.

First, open the muscle layers as laterally as possible because they are

thicker here and there is less chance of penetrating the peritoneum.

The muscle layers thin out, and the layers of the fascia become almost

joined medially. The peritoneum is very superficial. Inadvertent

penetration of the peritoneum is most likely just lateral to the rectus

sheath. Dissect through the external oblique and the internal oblique

muscle. Inferior to the internal oblique is the transversus abdominis.

Use care in inserting self-retaining retractors into the muscle layers

so as not to damage the peritoneum. Often, the transversus abdominis

muscle is a very thin or absent muscle layer. Bluntly spread this thin

muscle in line with its fibers to expose the transversalis fascia. -

Open the transversalis fascia in the lateral portion of the wound (Fig. 138.21).

Lift the transversalis fascia with Adson forceps and carefully open it

with blunt scissors. The retroperitoneal fat allows room to enter the

extraperitoneal space. Figure 138.21.

Figure 138.21.

Open the transversalis fascia in the lateral portion of the wound. Lift

it with Adson forceps and carefully open it with blunt scissors. -

Enter the retroperitoneal space

laterally. Identify the peritoneum and the fat of the peritoneal space.

Remove the peritoneum from the remaining transversalis fascia with

blunt dissection. Extend the incision after the peritoneum has been

safely removed. The sheath may be incised for added exposure. Torn

peritoneum should be repaired promptly (19). -

Identification of the psoas muscle is the

key to the retroperitoneal approach. Pass your hand directly to the

psoas. Avoid opening the retropsoas space, which is a blind pouch. The

genitofemoral nerve can be identified on the psoas. The spine is

immediately medial to the psoas and can be partially obscured by it.

Palpate and identify the psoas muscle, the intervertebral disc, the

aorta, and the vertebral body. The paravertebral sympathetic chain lies

medial to the psoas muscle. The ureter will be reflected medially with

the undersurface of the peritoneum. If a retroperitoneal abscess is

well developed, open it and dissect inside the abscess to the spine. -

The key at this point is to identify the

raised, white, softer disc by direct palpation with the finger, as

opposed to the lower, concave vertebral body, where the lumbar vessels

are found. The discs are the hills, and the vertebral bodies are the

valleys. The vessels are in the valleys. -

Once the lumbar disc can be identified,

insert a blunt elevator or padded small retractor to sweep the soft

tissue from left to right across the disc space. The lumbar veins are a

horizontal tether. Variations in formation of the inferior vena cava

and lumbar veins are the rule rather than the exception (11).

The most important of these veins is the iliolumbar vein, which crosses

the body of L-5 from right to left and ascends in the left paraspinous

area (13). This vessel is a direct tether to the left-to-right retraction of the aorta off the spine and is very vulnerable to avulsion. -

For operations on the L4–L5 disc space, identify the iliolumbar vein early in the dissection (Fig. 138.22).

Ligate it after clamping the vein with angled tonsil clamps and passing

two or three ligatures around the vein. These ligatures should not be

tied too close to the vena cava because a sidewall injury can occur.

Transect the vein after securing the permanent ties. Greater

mobilization of the vena cava and venous structures, left to right, is

thereby obtained. The iliolumbar vein consistently requires ligation.![]() Figure 138.22. For operations on the L4–L5 disc space, identify the iliolumbar vein early in the dissection.

Figure 138.22. For operations on the L4–L5 disc space, identify the iliolumbar vein early in the dissection. -

Lumbar veins of varying sizes at various

positions are always present. Some may be directly posterior to the

vena cava and of quite large diameter. Dissection on the anterior spine

consists of gentle stretching and pulling of the structures, blunt

dissection, direct pressure over many small bleeding areas with a

sponge, and a minimum of electrocautery. The paraspinous sympathetic

plexus between the spine and the psoas muscle

P.3651

varies

in size and number of fibers. Branches course between the preaortic and

paraspinous chains. Preserve paraspinous sympathetic fibers that do not

impede dissection. -

Dissect with the fingertip and blunt

elevators all the vascular structures from left to right to give

adequate visualization of the end plate of the vertebral body above the

disc (27). -

Use malleable Deaver-type retractors or

blade spike retractors around the disc space. Alternatively, prepare

four Freebody Steinmann pin retractors with rubber sleeves and mount

them in a Steinmann pin holder (9). For any

sharp stay-retractor that is driven into the body, stabilize the pin on

the finger and engage the tip into the vertebral body under direct

vision. The assistant taps the pin into the body while the surgeon

maintains control of the pin. Avoid the tendency for the pin to enter

the disc space by directing the tip of the pin horizontal to the disc

space. Allow a sufficient distance from the endplate to allow work on

the disc space without dislodging the pin. Place the superior and

inferior right-sided pins before placing the left-sided pins. -

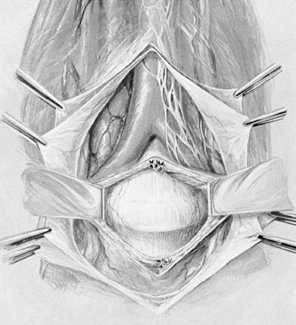

Expose the annulus of the disc (Fig. 138.23).

There should have been minimal sharp dissection and cautery in this

area. Now prepare the disc for the operative procedure. The vena cava

and iliac artery and vein are held by the retractors. Figure 138.23. Expose the annulus of the disc.

Figure 138.23. Expose the annulus of the disc. -

Special curved or malleable retractors can be used between the stay retractors for protection of the vena cava.

-

Extract the retractors with the same

amount of care as when they were inserted. The sheath and a finger must

guard the tip; otherwise the vena cava will be torn as the sharp tip

passes the vessel that is tented around it. -

Remember:

-

When making the incision, follow the skin guidelines for optimum spine exposure.

-

Achieve careful hemostasis in the muscle layers.

-

Incise the transversus abdominus muscle layer and the transversalis fascia in the lateral portion of the wound.

-

Beware of thinning muscle layers and the peritoneum’s superficial position medially near the rectus sheath.

-

Pass directly to the psoas muscle.

-

Identify the raised, soft, white disc.

-

Identify, ligate, and divide the iliolumbar vein.

-

Sweep prevertebral tissue left to right across the disc.

-

Insert the Steinmann pin after placing it directly on bone with the fingertip.

-

Retract the Steinmann pin, again with the fingertip preventing the tip of the pin from damaging the left iliac artery.

-

-

Palpate the spine with a finger and find

a disc for orientation. Usually, it is the L4–L5 disc. With

identification of the L4–L5 disc, palpate the pulse of the left common

iliac artery and the aortic bifurcation. The bifurcation of the aorta

is critical in determining the exact approach

P.3652

from this point. The usual bifurcation at the L4–L5 disc level was present in 69% of anatomic dissections performed by Harmon (11), but great variation exists. -

Palpate the left common iliac artery and

pass over it medially to the L5–S1 disc. By placement of the finger and

a subsequent blunt retractor such as a sponge-covered elevator, develop

a plane just to the right of the left common iliac artery. -

The left iliac vein lies within the

aortic bifurcation. It often courses directly on the surface of the

L5–S1 disc and may be flattened against the disc or L-5 body, with its

venous character obscured. Mobilize it to the left and cephalad with

the left iliac artery. -

The middle sacral artery and veins are

present in the bifurcation. The key to handling these structures is

blunt dissection just to the right of the left common iliac artery,

sweeping from left to right the prevertebral tissue, including the

middle sacral vessels and superior hypogastric plexus, off the

lumbosacral disc. Occasionally, the middle sacral vessels are of

formidable size, but seldom do they have to be ligated (4). -

An additional structure in the bifurcation is the superior hypogastric sympathetic plexus.

-

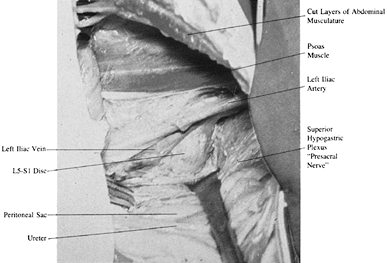

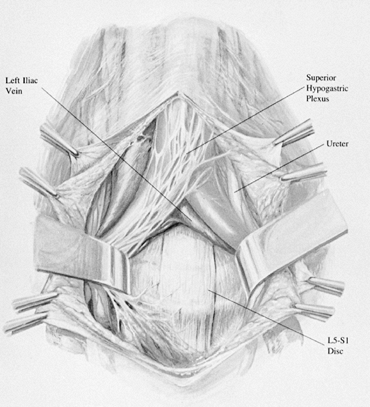

The thoracolumbar sympathetic chain

extends down anterior to the aorta and vertebral bodies in the

retroperitoneal space as the preaortic sympathetic plexus. At

approximately the L3–L4 level, the inferior hypogastric plexus extends

to L4–S1 as the superior hypogastric plexus (Fig. 138.24).

The structure of the superior hypogastric plexus varies considerably

because the preponderance of the superior hypogastric plexus fibers is

usually closer to the left iliac artery as they arch over the L5–S1

disc in the bifurcation of the aorta (Fig. 138.25) (16).

There may be multiple strands or one predominant large simple nerve

trunk. The superior hypogastric plexus contains the sympathetic

function for the urogenital system. The S1–S4 nerve roots that

contribute to the pelvic splenic nerves provide parasympathetic

function for the urogenital system. The pudendal nerve covers somatic

function from S-1, S-2, S-3, and S-4.![]() Figure 138.24.

Figure 138.24.

Sweep the prevertebral tissue bluntly off the front of the L5–S1 disc.

The superior hypogastric plexus may be a diffuse plexiform nerve

formation that is retracted with the other tissue, or it can be a

discrete well-defined presacral nerve. Figure 138.25. The superior hypogastric plexus is within the bifurcation of the aorta.

Figure 138.25. The superior hypogastric plexus is within the bifurcation of the aorta. -

Ejaculation is predominantly a

sympathetic function, whereas through control of the vasculature of the

penis, erection is predominantly a parasympathetic function. Retrograde

ejaculation and sterility result from disruption to the sympathetic

plexus. The main effect of damage to the superior hypogastric plexus is

improper closing of the bladder neck, with resultant retrograde

ejaculation, although the sympathetic fibers also have some effect on

the motility of the vas deferens, which is important in the

transportation of the spermatozoa from the epididymis to the seminal

vesicle (15). -

The prognosis for recovery from retrograde ejaculation is good (8).

Sperm can be obtained in refractory cases by bladder aspiration

techniques. Damage to the superior hypogastric plexus should not

produce impotence or failure of erection. Avoid damaging the

hypogastric plexus by doing the following (4):-

For the transperitoneal midline approach,

carefully open the posterior peritoneum and bluntly dissect the

prevertebral tissue from left to right (9). -

Visualize and retract the prevertebral

tissues by opening the posterior peritoneum higher over the bifurcation

and then extending the opening down over the sacral promontory (4,8,9,15). -

Remove the prevertebral tissue from the L5–S1 disc with blunt dissection, retraction, and spreading.

-

Attempt to retract the middle sacral

artery and vein without electrocautery by spreading and blunt

dissection. Use vascular clips or tie ligation when this vessel is of

considerable size. -

Until the annulus of the disc is clearly exposed, make no transverse scalpel cuts on the front of the L5–S1 disc.

-

Do not use electrocautery within the aortic bifurcation.

P.3653 -

-

The key to avoid damaging the superior

hypogastric plexus is to avoid transverse cuts on the face of the disc

until all the prevertebral tissue has been elevated from the annulus

and to avoid electrocautery on the surface of the L5–S1 disc. Small

bleeding points are encountered when doing this dissection, but they

are usually easily controlled by direct finger pressure or packing with

hemostatic gauze. Usually, the left iliac artery and vein will be

retracted to the left, but it may require retraction to the right on

occasion. -

Locate and ligate the iliolumbar vein before any mobilization of the left iliac artery to the right.

-

Always obtain radiographic confirmation

of the level. It can be done easily by inserting a #22-gauge spinal

needle and taking a radiograph. Because the L5–S1 disc and the sacrum

are often angled very horizontally, the body of L-5 can be mistaken for

the sacrum. -

Insert appropriate Freebody Steinmann pin stay-retractors, blade-point retractors, or hand-held retractors.

-

For the transperitoneal exposure, use

either a vertical midline incision or a transverse “smile” incision.

The “smile” is better cosmetically and gives excellent exposure, but it

requires transection of the rectus abdominus sheath. Identify and open

the rectus sheath, and transect the rectus abdominus muscle. The

posterior rectus sheath, the abdominal fascia, and the peritoneum are

conjoined in this area. Carefully open the posterior rectus sheath and

abdominal fascia to the peritoneum. -

Palpate the aorta and both iliac vessels through the posterior peritoneum. Feel the softer texture of the L5–S1 disc.

-

Inject the retroperitoneal space with saline to achieve separation of the peritoneum from the vascular structures.

-

Pick up the peritoneum with Adson forceps; handle it delicately.

-

Avoid use of the electrocautery anterior

to L5–S1 to prevent damage to the superior hypogastric plexus, despite

the fact that there is bleeding in this area. The left common iliac

vein often lies as a flat, white, bloodless ribbon across the L5–S1

disc within the aortic bifurcation. -

After the left common iliac artery and

left common iliac vein are identified, use blunt dissection to the

right of the left iliac artery and hypogastric plexus and soft tissue,

moving from left to right (Fig. 138.26).![]() Figure 138.26. Exposure of the L5–S1 disc. See text for a description of the technique.

Figure 138.26. Exposure of the L5–S1 disc. See text for a description of the technique. -

Bluntly dissect the middle sacral artery

and vein from left to right without sacrifice at this point.

Longitudinal blunt dissection allows better mobilization of these

vascular structures. When bleeding is encountered, use direct finger

and sponge pressure for a short time, followed by blunt dissection.

Control hemorrhage with packing and pressure. Divide and tie the middle

sacral artery and vein, if necessary.

-

Position the patient to allow full chest

excursion, to maintain the neck in a safe position, and to allow the

abdomen to hang completely free of pressure. Flex the hips and knees

enough to relieve nerve root tension but not so much as to obstruct

arterial flow to the legs or to produce any abdominal pressure. I

prefer the Andrews frame. -

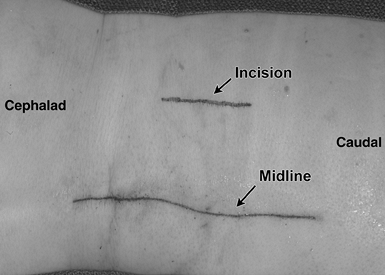

Obtain a skin marker radiograph by

inserting two #20-gauge spinal needles perpendicular to the skin

approximately three fingerbreadths lateral to the spine. Using the

alignment of the needles, put the skin incision in the midline over the

disc space. Paraspinous needles allow a more accurate skin incision

than a spinous process marker. -

Use a skin marking pencil to draw a

vertical, midline skin incision relative to the two needles over the

disc space. Make a dermal skin incision only. The average length is 3.2

cm for a one-level microscopic discectomy, longer for a more extensive

decompression. Inject 25 to 50 ml 1:500,000 epinephrine through the

dermal incision into the subcuticular tissue and directly down to the

lamina into the paraspinous muscle mass. Cut with a scalpel directly to

the fascial layer. Preserve the lumbodorsal fascial attachments to the

spinous process, the interspinous ligament, and the supraspinous

ligaments by making a paraspinous fascial incision that can be sutured

at closure without tension. This is preferable to removing all

soft-tissue fascial attachments from the spinous process, unless a

total laminectomy is to be done, in which the fascia is totally removed

from the spinous process and lamina with the electrocautery. -

The lumbodorsal fascia is critical for

stability of the spine. Maintaining the fascial attachments to the

spine is important and should be done when possible. The abdominal,

trunk, and gluteal muscles contract and tense the lumbodorsal fascia;

the fascia attachment to the spine allows these muscles to stabilize

the spine. -

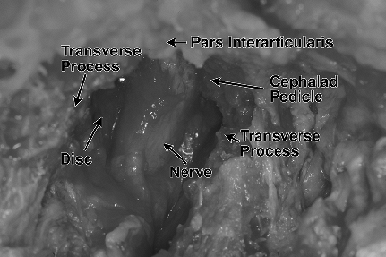

Make an incision into the lumbodorsal

fascia just lateral to the bulbous tips of the spinous processes.

Lengthen the fascial incision. Insert a Cobb elevator, with the tip

turned upward, onto the spinous process just under its bulbous tip, and

start the subperiosteal dissection. Then turn the elevator bevel down.

Dissect, identify by touch the cephalad and then the caudad lamina, and

clear the interlaminar area. Take care not to cut through the outer

cortex of the lamina. Sweep the superficial soft tissue off the

interlaminar area laterally out to the facet joint capsule. Do not

damage the capsule. Protect the facet joint capsule. Remember that the

two laminae and their interlaminar areas are the only areas that need

be exposed for an operation on one intervertebral disc. -

Following exposure of the intralaminar

area, place a Williams self-retaining retractor with the blade

retracting laterally over the facet joint capsule with the pointed tip

placed medially. For larger, bilateral exposures, I use the Wiltse

retractors with both sides exposed similarly. -

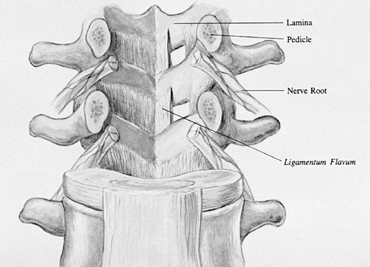

The superficial ligamentum flavum blends

laterally into the facet joint capsule. Incise the superficial

ligamentum flavum with the #15 blade or electrocautery laterally or at

the junction of the superficial ligamentum flavum and the facet joint

capsule. Use a curet to elevate the superficial ligamentum flavum from

the deep ligament moving from lateral to medial. Remove the superficial

ligament with a pituitary rongeur. The vertical striations of the

yellow deep ligamentum flavum can be seen in the depths of the

interlaminar area. Use an angled curet to clear under the caudal edge

of the cephalad lamina and a straight curet to define the ligamentum

flavum attachment to the caudad lamina (Fig. 138.27). Expose the deep portion of the ligamentum flavum’s vertical striations. Figure 138.27.

Figure 138.27.

This underview of the posterior elements from the intervertebral canal

demonstrates the ligamentum flavum and its insertion on the lamina. -

Several factors concerning the anatomy of the ligamentum flavum are important:

-

It has a deep and superficial portion.