Hematologic Malignancies

Editors: Tornetta, Paul; Einhorn, Thomas A.; Damron, Timothy A.

Title: Oncology and Basic Science, 7th Edition

Copyright ©2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Section II – Specific Bone Neoplasms and Simulators > 9 – Hematologic Malignancies

9

Hematologic Malignancies

Valerae O. Lewis

Hematologic malignancies such as lymphoma and myeloma

can manifest in bone, and these osseous manifestations can often be the

first presentation of the systemic disease. After metastatic disease,

myeloma and lymphoma are the second and third major categories in the

differential diagnosis of an aggressive bone lesion in an adult. To

avoid unnecessary surgery and to create a definitive treatment plan, it

is important to become familiar with the presentation and the work-up

of these lesions. Often the orthopaedic surgeon is the first to

diagnose these diseases; however, surgical intervention may not be

required. In addition, because the principles for treatment of

hematologic malignancies differ so greatly from sarcomas, the diagnosis

must be established before initiation of treatment.

can manifest in bone, and these osseous manifestations can often be the

first presentation of the systemic disease. After metastatic disease,

myeloma and lymphoma are the second and third major categories in the

differential diagnosis of an aggressive bone lesion in an adult. To

avoid unnecessary surgery and to create a definitive treatment plan, it

is important to become familiar with the presentation and the work-up

of these lesions. Often the orthopaedic surgeon is the first to

diagnose these diseases; however, surgical intervention may not be

required. In addition, because the principles for treatment of

hematologic malignancies differ so greatly from sarcomas, the diagnosis

must be established before initiation of treatment.

Lymphoma

The vast majority of cases of lymphoma involving bone

are non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is not a

single disease, but a group of closely related B- and T-cell cancers of

the lymphatic system. B-cell lymphomas represent 85% of NHL cases.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma can start in the lymph nodes or lymphatic tissue

such as the spleen, stomach, or skin, and because lymphocytes circulate

throughout the lymphatic vessels and bloodstream, abnormal lymphocytes

can reach any organ. Thus, lymphoma can manifest in any organ. In fact,

along with lung carcinoma, lymphoma is one of the most common

malignancies that may manifest as soft tissue metastases.

are non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is not a

single disease, but a group of closely related B- and T-cell cancers of

the lymphatic system. B-cell lymphomas represent 85% of NHL cases.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma can start in the lymph nodes or lymphatic tissue

such as the spleen, stomach, or skin, and because lymphocytes circulate

throughout the lymphatic vessels and bloodstream, abnormal lymphocytes

can reach any organ. Thus, lymphoma can manifest in any organ. In fact,

along with lung carcinoma, lymphoma is one of the most common

malignancies that may manifest as soft tissue metastases.

Epidemiology

-

Incidence of NHL is increasing.

-

Worldwide incidence has risen steeply from the 1970s to the 2000s.

-

From a relatively rare disease to the fifth most common cancer in the United States

-

-

Purported reasons for rise

-

Increasing exposure to chemicals

-

Increasing incidence of viral infections

-

Increasing incidence of organ transplantation

-

Increasing number of blood transfusions

-

Classification

-

Revised European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms (REAL) (Table 9-1)

-

Most common types: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (45%) and follicular (25%) lymphomas

-

-

Clinical classification

-

Low grade (indolent), intermediate, or aggressive (high grade)

-

Based on the natural history of the disease

-

-

Modified Ann Arbor Staging System (Table 9-2)

-

Describes extent of disease

-

International Prognostic Index (IPI: an excellent prognostic tool)P.245

-

Clinical stage (I/II versus III/IV)

-

Number of extranodal sites (0 or 1 versus >1)

-

Lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) (normal versus >1)

-

Age at diagnosis

-

Performance status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG])

-

-

The IPI can identify prognostic groups,

and for patients with IPI >2 peripheral stem cell or bone marrow

transplantation should be considered.

-

-

|

Table 9-1 Real (Revised European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms) Classification of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Table 9-2 Modified Ann Arbor Staging System

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Diagnosis

Clinical Findings

-

Painless swelling of lymph nodes

-

Chills

-

Fever

-

Night sweats

-

Malaise

-

Unexplained weight loss

Staging Studies

-

Biopsy of lesion/lymph nodes

-

Computed tomography (CT) scan

-

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan

-

Bone marrow biopsy

Treatment

-

Depends on stage of disease

-

Multimodality

-

Combination of chemotherapy and radiation

-

CHOP with rituximab

-

CHOP: cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

-

Rituximab: works by targeting the CD20 antigen on normal and malignant B cells

-

-

-

Peripheral stem cell transplantation

-

Bone marrow transplantation

Primary Lymphoma of Bone

Primary lymphoma of bone (PLB) is a distinct clinical

entity. Although it was first identified by Oberlin in 1928, it was not

until 1939, when Parker and Jackson reported on their series of

“reticulum cell sarcoma,” that lymphoma of bone was classified distinct

from systemic lymphoma.

entity. Although it was first identified by Oberlin in 1928, it was not

until 1939, when Parker and Jackson reported on their series of

“reticulum cell sarcoma,” that lymphoma of bone was classified distinct

from systemic lymphoma.

-

Definition: malignant lymphoid infiltrate within bone with or without cortical invasion or soft tissue extension but without concurrent involvement of regional lymph nodes or distant viscera

-

Synonyms

-

Reticulum cell sarcoma (misnomer; not a sarcoma)

-

Malignant lymphoma of bone

-

Primary skeletal lymphoma

-

Osteolymphoma

-

Epidemiology

Diagnosis

Clinical Findings

-

Localized bone pain

-

Mass

-

Pathologic fracture in 20% to 30%

-

Generally not systemically ill

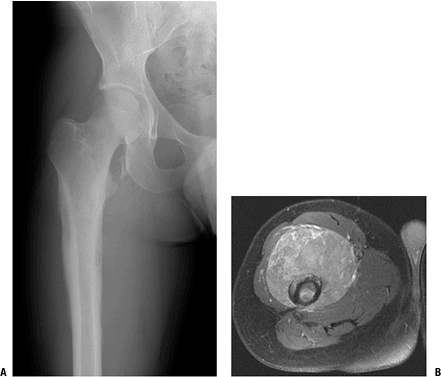

Radiologic Findings (Fig. 9-1)

Plain Radiographs

-

Diaphyseal

-

Permeative/mottled

-

Poorly marginated

-

Associated soft tissue mass

|

|

Figure 9-1

Anteroposterior radiograph of the proximal femur and MRI (axial T1 with contrast) of a 20-year-old man with primary lymphoma of bone. Note permeative changes in the diaphysis of the femur on the radiograph and large enhancing soft tissue mass demonstrated on the MRI. |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

-

Large soft tissue mass

-

Enhances with gadolinium

Histologic Findings

-

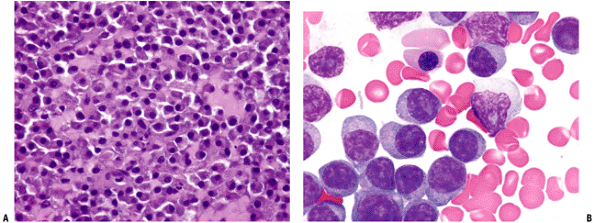

Sheet-like proliferation of round blue cells without significant matrix (Fig. 9-2)

-

Pleomorphic

-

Nuclear heterogeneity

-

Special stains

-

Reticulum stains

-

Leukocyte common antigen (LCA)

-

CD45

-

-

B-cell marker

-

CD19, CD20

-

-

Treatment

-

Multidisciplinary: combination of

systemic chemotherapy and local radiation is thought to be the most

effective treatment in decreasing the local recurrence and systemic

relapse-

Chemotherapy: CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone)

-

Rituximab (monoclonal antibody to CD20)

-

-

Radiation: to the local site

-

Surgery: limited to diagnostic biopsy and to prevent impending pathologic fractures or to repair actual pathologic fractures

P.247

|

|

Figure 9-2 Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of bone: (A) 20× magnification, (B) 40× magnification.

|

Prognosis

-

60% to 80% 5-year survival rate

-

Worsens with age

Multiple Myeloma

Multiple myeloma is a plasma cell dyscrasia, but it is

not the only such entity. Other plasma cell dyscrasias sometimes

encountered in orthopaedic oncology include monoclonal gammopathy of

uncertain significance (MGUS) and solitary plasmacytoma. Both MGUS and

plasmacytoma may progress, and often do, to the disseminated form,

multiple myeloma.

not the only such entity. Other plasma cell dyscrasias sometimes

encountered in orthopaedic oncology include monoclonal gammopathy of

uncertain significance (MGUS) and solitary plasmacytoma. Both MGUS and

plasmacytoma may progress, and often do, to the disseminated form,

multiple myeloma.

-

Definition: disseminated malignancy of monoclonal plasma cells

-

Monoclonal proteins

-

IgG: 60%

-

IgA: 20%

-

IgD: 2%

-

IgE: 0.1%

-

Light-chain kappa or lambda: 18%

-

Biclonal: <1%

-

Nonsecretory: <5%

-

-

Pathophysiology

-

Increased expression by osteoblasts of the receptor activator of nuclear factor KB (NF–KB) ligand (RANKL) and a reduction in the level of its decoy receptor osteoprotegerin

-

The increase in the ratio of RANKL to osteoprotegerin results in activation of osteoclasts and bone resorption.

Epidemiology

-

1% of all malignancies

-

14,400 new cases/year

-

Male:female 1.8:1

-

Age: 50s to 70s

-

Median 65 years

-

-

Race propensity

-

African Americans > Caucasians (2:1)

-

-

Risk factors: obesity, genetics (HLA), immunological challenges

Diagnosis

Clinical Findings

-

Pain

-

Pathologic fracture

-

Bone marrow failure

-

Anemia: fatigue and weakness

-

Thrombocytopenia: bruising, bleeding

-

Neutropenia: recurrent infections (gram-negative infections)

-

-

Renal insufficiency (50%): multifactorial

-

Bence Jones protein precipitation

-

Interstitial nephritis

-

Hypercalciuria

-

-

Hypercalcemia (25%)

-

Manifestations

-

Nausea

-

Muscle weakness

-

Confusion

-

Polyuria

-

Constipation

-

-

Treatment

-

Diagnostic criteria

-

10% plasma cells in the bone marrow

-

Monoclonal protein in the serum (serum protein electrophoresis) or urine (urine protein electrophoresis)

-

Evidence of end-organ failure (CRAB)

-

Hypercalcemia

-

Renal insufficiency

-

Anemia

-

Bone lesions

-

-

-

Diagnostic Work-Up

-

Serum protein electrophoresis

-

Monoclonal gammopathy does not automatically signify multiple myeloma.

-

MGUS

-

IgG peak slightly elevated

-

IgG ≤3.5 g/dL, IgA ≤2 g/dL, urine light chain ≤1 g/dL

-

-

Normal radiographs

-

< 10% plasmacytosis

-

No symptoms

-

-

-

Urine protein electrophoresis

-

Monoclonal gamma globulin spike

-

Quantitative Ig levels

-

-

Serum chemistries

-

Complete blood count (may show anemia)

-

Electrolytes

-

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, calcium (may show azotemia, hypercalcemia)

-

-

β2-microglobulin

-

-

Bone marrow aspiration

-

Plasmacytosis >10%

-

-

Bone survey

-

Bone scan can underestimate extent of disease.

-

80% of lesions are “cold.”

-

-

Spine MRI

-

Vertebral lesions difficult to visualize on plain film

-

-

-

Biopsy: need for biopsy can be alleviated

in the face of multiple osseous lesions on bone survey and a positive

serum/urine protein electrophoresis.

Radiologic Findings

-

Punched-out lytic lesions (Fig. 9-3): single or multiple

Histologic Findings

-

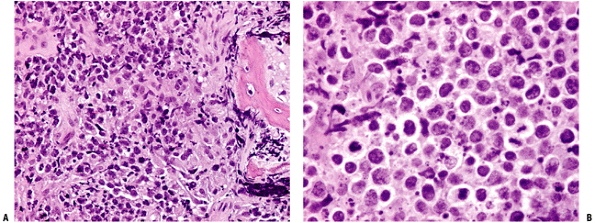

Uniform plasma cells (Fig. 9-4)

-

Large round nuclei

-

Clockface

-

Eccentric

-

-

Distinct cell borders

-

Abundant cytoplasm, perinuclear clearing

|

|

Figure 9-3 Lateral radiograph of skull displaying “salt-and-pepper” punched-out lesions of multiple myeloma.

|

Treatment

Local Treatment

-

Radiation (very sensitive)

-

Surgical adjuvant (postoperative): 30 Gy

-

Radiation alone

-

Moderate, symptomatic lesions without impending or actual fracture

-

<50% cortex, <2.5 cm

-

-

-

Surgery

-

Large lesions

-

Impending pathological fracture

-

Actual pathological fracture

-

-

Protect the whole bone

-

Intramedullary rod fixation

-

-

-

Perioperative management

-

Highly vascular

-

Preoperative embolization of lesion important to consider

-

Type and cross-match

-

Even for closed nailing

-

-

-

Acute renal failure

-

Hydrate the patient well!

-

Systemic Treatment

-

Chemotherapy and corticosteroids: If

patient is eligible for stem cell transplantation, alkylating agents

for induction chemotherapy should be avoided.-

Pulsed steroids alone

-

Melphalan + prednisone (MP)

-

Vincristine + doxorubicin (Adriamycin) + dexamethasone (VAD)

-

Thalidomide and dexamethasone: anti-angiogenic

-

Bortezomib (Velcade, PS-341): proteasome inhibitor

-

-

Stem cell transplantation

-

Autologous stem cell transplantation

-

Can prolong disease-free survival and overall survivalP.249

![]() Figure 9-4

Figure 9-4

Representative pathology sections from a multiple myeloma specimen.

Note eccentric nuclei, abundant cytoplasm, and distinct cell borders. (A) Tissue section (20×). (B) Cytology on touch prep (80×). -

Can be done in tandem

-

Can be used as salvage therapy

-

Induction chemotherapy before stem cell harvest reduces the tumor burden.

-

-

Allogenic stem cell transplantation

-

Transplant not contaminated with tumor cells

-

Only 5% to 10% of patients are candidates.

-

High mortality rate

-

-

Prognosis

-

Median survival 3 years

-

Overall survival depends on stage.

-

International Staging System (Table 9-3): based on serum β2-microglobulin and albumin levels

Solitary Plasmacytoma of Bone

Pathophysiology

-

Rare presentation of a plasma cell dyscrasia

-

3% of patients with myeloma

-

Early manifestation of multiple myeloma: 70% progress to multiple myeloma

-

Epidemiology

-

Male:female 3:1

-

Age of presentation younger than multiple myeloma

-

Most common locations

-

Long bones

-

Pelvis

-

Spine

-

Diagnosis

-

Solitary bone lesion

-

Skeletal survey: normal

-

MRI skull/spine/pelvis: normal

-

Bone marrow: normal plasma cell count

-

No anemia, hypercalcemia, or renal disease

-

Normal serum/urine protein electrophoresis or serum protein electrophoresis that becomes normal after treatment of the lesion

Treatment

-

Radiation only (45 Gy)

-

Exquisitely sensitive

-

Rapid response

-

|

Table 9-3 International Staging System for Multiple Myeloma with Corresponding Median Survival

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

P.250

Prognosis

-

Relatively good

-

20% remain free of disease >10 years.

-

Better than multiple myeloma

Suggested Reading

Baiocchi OC, Colleoni GW, Rodrigues CA, et al. Importance of combined-modality therapy for primary bone lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2003;44(10):1837–1839.

Kilborn

TN, Teh J, Goodman TR. Paediatric manifestations of Langerhans cell

histiocytosis: a review of the clinical and radiological findings. Clin Radiol 2003;58(4):269–278.

TN, Teh J, Goodman TR. Paediatric manifestations of Langerhans cell

histiocytosis: a review of the clinical and radiological findings. Clin Radiol 2003;58(4):269–278.

Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2004;351(18):1860–1873.

Lewis VO, Primus G, Anastisi J, et al. Oncologic outcomes of primary lymphoma of bone in adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003;(415):90–97.

Yasko

AW, Fanning CV, Ayala AG, et al. Percutaneous techniques for the

diagnosis and treatment of localized Langerhans-cell histiocytosis

(eosinophilic granuloma of bone). J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1998;80(2):219–228.

AW, Fanning CV, Ayala AG, et al. Percutaneous techniques for the

diagnosis and treatment of localized Langerhans-cell histiocytosis

(eosinophilic granuloma of bone). J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1998;80(2):219–228.

Zinzani PL. Lymphoma: diagnosis, staging, natural history, and treatment strategies. Semin Oncol 2005;32(1 Suppl 1):S4–10.