Ewing Sarcoma and Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor of Bone

II – Specific Bone Neoplasms and Simulators > 6 – Bone Sarcomas >

6.2 – Ewing Sarcoma and Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor of Bone

very few survivors, prior to the use of chemotherapy, surgical

resection, and radiation. The disease manifests as chronic increasing

pain in the area of a lytic, destructive bone lesion of flat bones and

the diaphysis of long bones. The initial presentation is frequently

confused with osteomyelitis, and it can be mistakenly treated as that

for a period of time before the diagnosis is established. Ewing sarcoma

and a less virulent related disease, primitive neuroectodermal tumor of

bone (PNET), metastasize to lung,

bone,

and bone marrow most frequently. Current management includes biopsy,

staging, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgical resection and/or radiation,

and further chemotherapy. The 5-year survival rate is 60% to 65% for

nonmetastatic disease and 25% to 30% for metastatic disease.

-

Unknown; associated with reciprocal

translocation of chromosomes 11 and 22 (90% of cases), which involves

bands q24 and q12 of both chromosomes respectively -

This results in a new chimeric EWS/FLI-1

fusion product, which produces the EWS/FLI-1 or MIC2 protein, stained

for by the CD99 immunohistochemistry marker.

-

Third most common primary bone sarcoma (after osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma, respectively)

-

Three times less common than osteosarcoma

-

Rare in African-Americans (0.5% of Ewing cases); peak incidence in the second decade of life

-

Male:female ratio 1.3:1

-

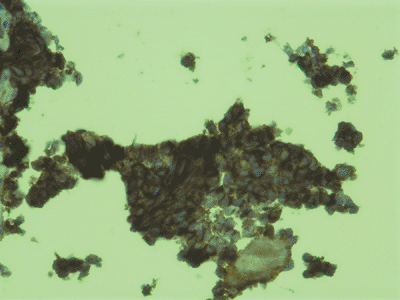

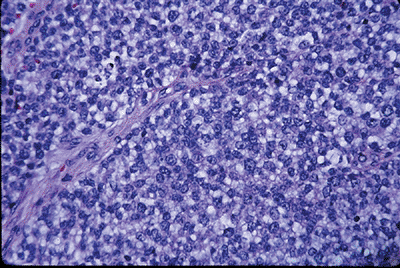

Sheets of monotonous, small, round blue cells with indistinct cytoplasm (Fig. 6.2-1)

-

Glycogen granules in the cytoplasm can be seen after periodic acid Schiff (PAS) staining or with electron microscopy.

-

PAS-positive granules sensitive to digestion with diastase

Figure 6.2-1

Figure 6.2-1

This hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E) staining shows typical Ewing

sarcoma features of monotonous sheets of small, round blue cells with

indistinct cytoplasm.![]() Figure 6.2-2

Figure 6.2-2

This CD-99 immunohistochemical staining shows positivity that is

consistent with Ewing sarcoma. Cytogenetics is used to confirm

Ewing/PNET (t11:22). -

The nuclear chromatin is finely granular, with one to three small nucleoli per nuclei.

-

CD99 immunohistochemistry marker stains for EWS/FLI1 fusion or MIC2 protein, which is present in 90% of cases. (Fig. 6.2-2)

-

Ewing sarcoma: most common, least differentiated, worst prognosis

-

PNET: more neural differentiation, better prognosis

-

Askin’s tumor: primary in thoracopulmonary region, best prognosis

-

Typical age at diagnosis: 5 to 30 years

-

Rare in patients <5 years old; this distinguishes it from metastatic neuroblastoma

-

Usually presents as a painful mass

-

May be accompanied by fever and weight loss, which are poor prognostic signs

-

Location

-

Mostly, lytic destructive lesion with “onion-skinning” periosteal reaction (Figs. 6.2-3, 6.2-4, 6.2-5, 6.2-6, 6.2-7, and 6.2-8)

-

90% of patients have soft tissue mass.

-

A destructive, lytic, diaphyseal lesion in a child is two times more likely to be a Ewing sarcoma than an osteosarcoma.

-

A destructive, lytic, metaphyseal lesion in a child is 12 times more likely to be an osteosarcoma than a Ewing sarcoma.

-

Traditionally surgery for Ewing sarcoma was reserved for expendable bones.

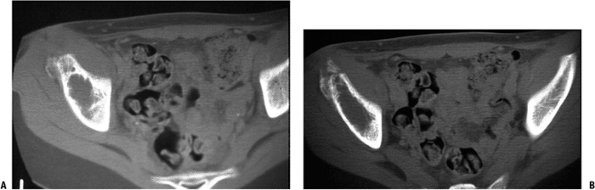

![]() Figure 6.2-4 Computed tomographic scans demonstrating the lytic destructive changes of the ilium.

Figure 6.2-4 Computed tomographic scans demonstrating the lytic destructive changes of the ilium. Figure 6.2-5 Anteroposterior radiograph of a 19-year-old with chronic hip pain. Note the cortical destruction and periosteal changes.P.190

Figure 6.2-5 Anteroposterior radiograph of a 19-year-old with chronic hip pain. Note the cortical destruction and periosteal changes.P.190![]() Figure 6.2-6

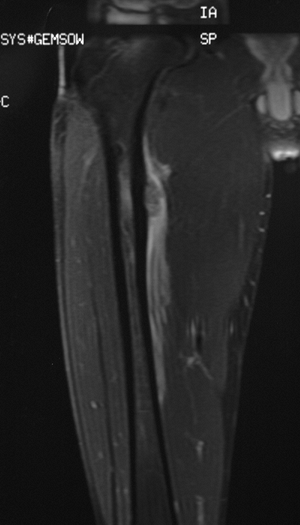

Figure 6.2-6

Magnetic resonance imaging shows large area of soft tissue involvement

without a stress fracture. This was diagnosed as a Ewing sarcoma of

bone and was treated with chemotherapy, wide resection, and bone

grafting. -

Because of improved local control with

surgery compared to radiation alone, most Ewing sarcoma patients have

surgical resection if adequate margins are attainable and the defect is

reconstructable (Fig. 6.2-9). -

Spine and acetabulum are sites that pose difficulties with resection and reconstruction.

-

Most resections are reconstructed with bone-grafting procedures.

-

Frequent diaphyseal location lends itself to intercalary allograft reconstruction.

-

Young age (small skeletal size) often requires expandable prostheses if growth plate has to be resected.

-

|

|

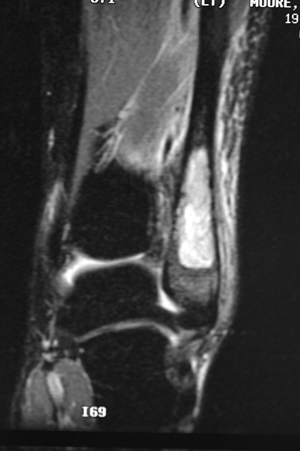

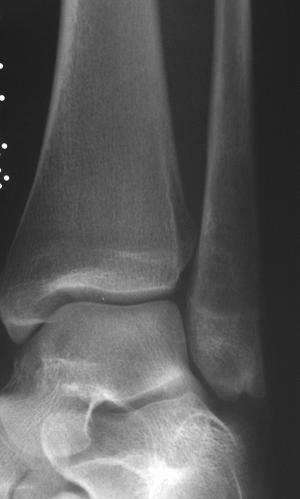

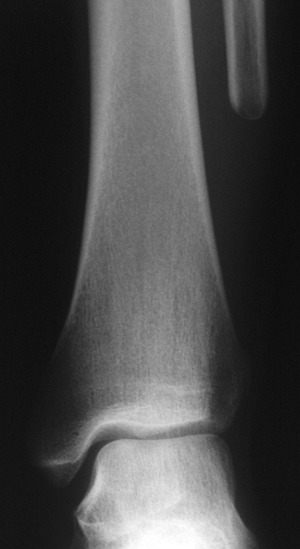

Figure 6.2-7 Subtle distal fibula lytic lesion without periosteal signs.

|

-

Local relapse rate with radiation alone is 25%; with surgery and radiation it is 8%.

-

It is unclear whether this difference affects survival.

-

Five-year disease-free survival rate for non-metastatic Ewing sarcoma is 60% to 65%.

-

Recurrent disease after 5 years for patients with nonmetastatic disease is very unusual.

-

-

Five-year survival rate for patients with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis is 25% to 30%.

-

Early postoperative pain control is very important.

-

Patient-controlled analgesia

-

Regional and epidural pain management

-

-

Early rehabilitation emphasizing range of motion is critical.P.191

![]() Figure 6.2-8 Magnetic resonance imaging shows marrow replacement with tumor. This was diagnosed as a Ewing sarcoma.

Figure 6.2-8 Magnetic resonance imaging shows marrow replacement with tumor. This was diagnosed as a Ewing sarcoma. Figure 6.2-9

Figure 6.2-9

The patient was treated with wide resection and chemotherapy. No

reconstruction was performed, and no instability of the ankle was noted

on follow-up examinations. -

Avoid weight bearing until after bony union.

-

Long-term antibiotics for segmental allografts

G, Ferrari S, Longhi A, et al. Local and systemic control in Ewing’s

sarcoma of the femur treated with chemotherapy, and locally by

radiotherapy and or surgery. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2003;85:107–114.

ME, Gehan EA, Burgert EO, et al. Multimodal therapy for the management

of primary, nonmetastatic Ewing sarcoma of bone: A long-term follow-up

of the first intergroup study. J Clin Oncol 1990;8:1664–1674.

P, Rougraff BT, Bacci G, et al. Prognostic significance of

histopathologic response to chemotherapy in nonmetastatic Ewing’s

sarcoma of the extremities. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:1763–1769.