CHAPTER 48 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 48 – Allograft Meniscus Transplantation: Dovetail Technique

The meniscus provides many functions for the well-being of the knee, including load bearing, joint stability, and congruency. With so many roles in maintaining normal knee function, it is of little debate that excision results in an increased risk of arthritis. Unfortunately, the ideal replacement for the meniscus has yet to be discovered. At present, meniscal allografts have served as the most successful substitute. Whereas the durability and the ability to prevent or to delay arthritis are questioned, studies have shown that patients typically have less pain and improved function after meniscus implantation. However, the indications are narrow, and the procedure is technically challenging.

Many surgical methods have been described for meniscal allograft transplantation. They are typically classified into two broad categories on the basis of securing the meniscus at its attachments sites with bone or without bone. Although bone fixation techniques are more difficult, several basic science studies have shown that they more closely replicate normal meniscus stress force protection. With this fact, until clinical studies show otherwise, bone fixation methods are recommended.

Within the bone fixation category, several techniques are used. These include bone plugs, keyhole method, slot technique, and dovetail technique. Each has its pros and cons. I prefer the dovetail technique for lateral meniscus and bone plugs for medial meniscus. The rationale for the medial side takes into consideration that the distance between the anterior and posterior horns is several centimeters, with a highly variable anterior attachment site. By having the horns separate (i.e., two separate bone plugs), it enables placement of the bone plugs to match the native meniscus insertion sites. Because the anterior and posterior horns of the native lateral meniscus are close, maintaining a bone bridge between the horns is recommended. The dovetail method enables not only preparation of the channel under direct observation but also a press-fit fixation.

Although it is intuitive, the first item is confirmation that the meniscus has been excised. Intraoperative photographs, operative reports, and magnetic resonance imaging studies should be available. If any doubt remains, diagnostic arthroscopy should be performed.

The typical history for appropriate candidates is as follows:

Appropriate candidates typically have minimal physical findings beyond joint line tenderness and, at most, mild joint effusions.

More often, patients have findings that may preclude surgical candidacy:

Include a magnification marker for reference in graft sizing.

Magnetic resonance imaging is performed if there is a question of degree of meniscectomy, associated pathologic change, to degree of stress reaction of bone.

A bone scan is obtained if there is a question of stress to the involved knee compartment. However, use has declined with advancement of magnetic resonance imaging techniques.

Indications and Contraindications

The ideal candidate is a patient who has had a prior meniscectomy in an otherwise normal knee and experiences pain localized to this compartment. The degree of articular cartilage damage is slight with no greater than Outerbridge grade II chondrosis in the involved compartment. Patients with grade III chondrosis may also be candidates, but not grade IV, unless it is a discrete defect that can be corrected before or at the time of meniscal implantation. Associated pathologic processes, such as ligament instability and limb malalignment, provided correction can be performed, do not exclude patients.

Contraindications are advanced arthrosis of the involved compartment and diffuse knee joint chondrosis. Comorbidities that are not correctable are exclusion criteria. Obesity, inflammatory arthropathy, and avascular necrosis are also contraindications. Unrealistic expectations of the patient should also be taken into consideration (the knee will not be returned to normal).

Ligament instability and contained chondral defects are addressed at the time of the meniscus implantation. Controversy exists as to whether limb realignment should be performed any time the mechanical axis passes through the involved compartment or only if there is a measurable difference between the two legs. Apart from this debate, limb realignment procedures are usually performed when the meniscus is implanted.

If both osteotomy and ligament reconstructions are necessary, it is common to stage the procedures because of the concern of tunnel or screw overlap and associated adequate fixation. My preference is to perform the osteotomy first and, after healing, then the meniscus and ligament reconstructions.

Various methods have been used for sizing of meniscal allografts to match the host. Whereas magnetic resonance images and computed tomographic scans can be used, plain radiographs are the most common means. Anteroposterior and lateral views are obtained with a magnification marker placed at the level of the joint line. Any obliquity or rotation that may affect measurement of the tibial plateau is not acceptable. Tissue banks do not have uniform methods of sizing. Therefore, if any question is present, it is wise to verify the size match.

Meniscal Graft Processing and Preservation

Although the risk of disease transmission from meniscal allografts is minimal, it still exists. It is thus prudent to diminish risk of contamination even further by making certain the tissue bank is certified by the American Association of Tissue Banks. To obtain the certification, the bank must follow stringent methods of procurement and processing of the allograft tissue.

Grafts can be fresh, cryopreserved, or frozen. Fresh grafts are typically not used because of the increased risk of disease transmission. Whereas some degree of cell viability is able to be achieved with cryopreservation, the clinical benefit compared with frozen grafts, which are acellular, has not been answered. Lyophilization (i.e., freeze-drying) eliminates contamination, but it is not recommended because of the deleterious effect it has on the structural integrity of the meniscal allograft.

The procedure is typically performed under general anesthesia. The patient’s position and setup are the same as the surgeon’s preference in performing a meniscus repair.

Surgical Landmarks, Incisions, and Portals

| • | Patella | |

| • | Patellar tendon | |

| • | Tibial plateau | |

| • | Fibular head (lateral meniscus) |

| • | Posteromedial approach: saphenous nerve | |

| • | Posterolateral approach: peroneal nerve, popliteal tendon |

Examination Under Anesthesia and Diagnostic Arthroscopy

The meniscal allograft should not be opened before a complete physical examination of the knee and diagnostic arthroscopy are performed. Their significance is to confirm that the patient is a candidate for a meniscal allograft.

Specific Steps (

Box 48-1

)

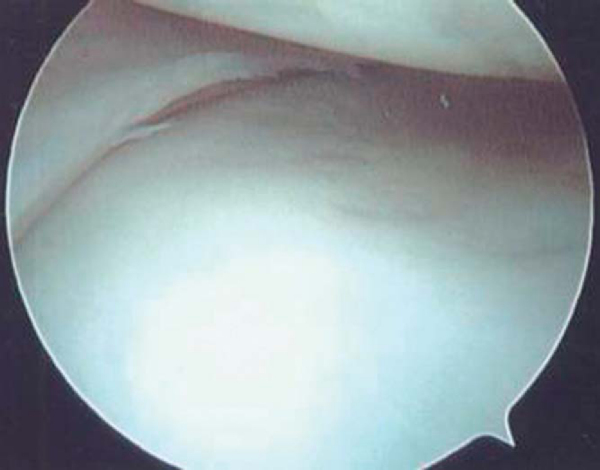

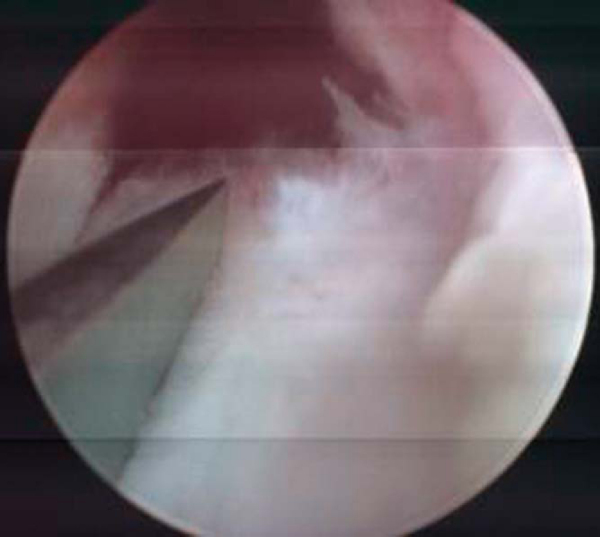

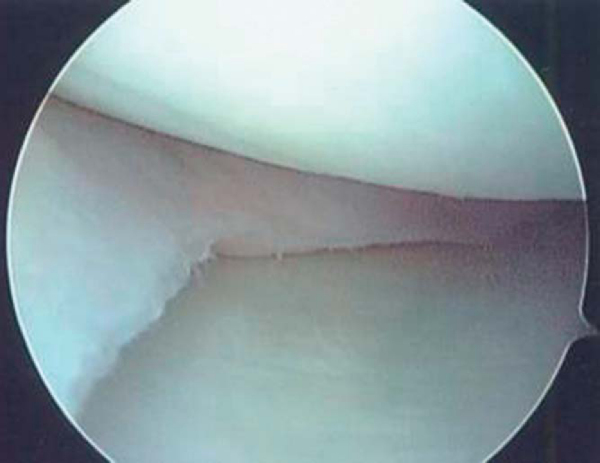

1. Arthroscopic Host Site Preparation

The initial arthroscopic portal should be established on the side opposite the graft, immediately adjacent to the patellar tendon border. This enables passage of the scope through the notch and visualization of the posterior horn attachment. Before the graft-side portal is made, a spinal needle is used to confirm that the portal site is directly in line with the horn attachments. Any obliquity in the skin incision to the horn attachments can cause difficulty in the proper orientation when the bone channel is prepared. Once the portals are made, the meniscal remnant is débrided to approximately a 2-mm vascular rim (Figs. 48-1 and 48-2 [1] [2]). The anterior portion of the meniscus can be addressed after the arthrotomy is made. To ensure proper channel height and alignment, a burr is used to remove the tibial spine to a height that is equal to the level of the tibial plateau articular cartilage and straight in line with the attachment sites. If there is still any difficulty in full visualization of the posterior horn attachment, a limited notchplasty should be performed. Likewise, the entire anterior attachment needs to be seen to be used as a reference for initial placement of the osteotome. Although a tourniquet can be inflated at any time, it is typically not done so until this point. By waiting, it allows confirmation of a vascular rim and conserves tourniquet time. Higher pressure and inflow rates are often needed to limit bleeding during bone channel preparation, which is why the tourniquet may be required at this point in the case.

| Surgical Steps | |||||||||||||||

|

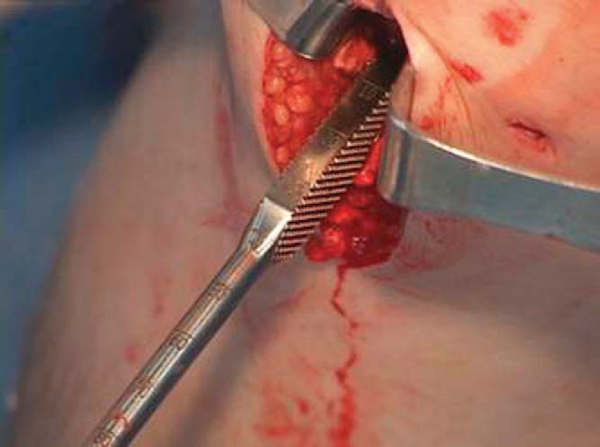

The ipsilateral portal is extended to approximately 3 cm in length. The osteotome is brought into the knee and used as a guide for further channel preparation. It follows the initial trough and is placed at the most central aspect of the knee near the notch (hugging the tibial anterior cruciate ligament insertion) to allow room for proper drill placement. A guideline on the osteotome is followed to ensure the proper depth in the tibial plateau at all times (

Fig. 48-3

). The osteotome should be inserted to 1 or 2 mm just short of the back of the plateau to maintain a back wall and prevent overinsertion of the graft. The initial osteotome attachment guide is placed and allows a 6-mm drill to initiate the channel under direct visualization (

Fig. 48-4

). The second osteotome attachment is used for a 7-mm drill placement just beneath the level of the first drill (

Fig. 48-5

). A rasp and tamp finish the dovetail slot by expanding the channel and compressing the cancellous bone at it borders (Figs. 48-6 and 48-7 [6] [7]).

|

|

|

|

Figure 48-3 |

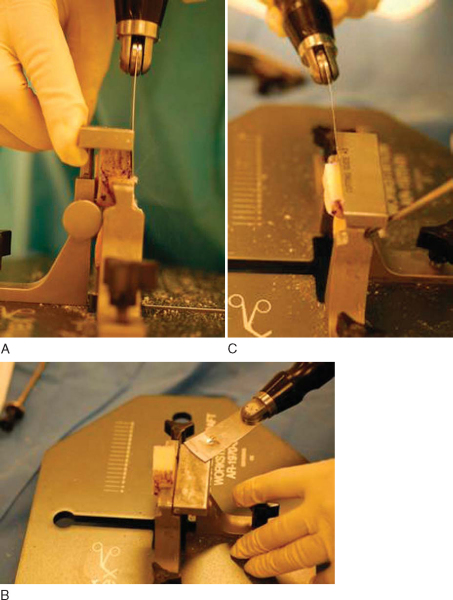

2. Meniscal Allograft Preparation

One of the main benefits of the dovetail method is the use of cutting guides to prepare the graft, rather than preparation of the graft by a freehand technique. As a result, it not only saves time but, more important, decreases the chance of an improper match between the recipient channel and graft. The graft is initially sawed so that the horn attachments are flush with the ends of the allograft bone, and the graft is marked with the dovetail template (

Fig. 48-8

). It is then inserted upside-down into the graft station and secured with the side attachments. The three cutting guides are then used in sequential order to cut the bone, resulting in a dovetail design (

Fig. 48-9

).

The dovetail graft sizer is used to confirm that the allograft will slide through the channel, but with a snug fit so that it will maintain a press fit (

Fig. 48-10

). Any minor adjustments should be made at this time rather than attempted during insertion of the graft.

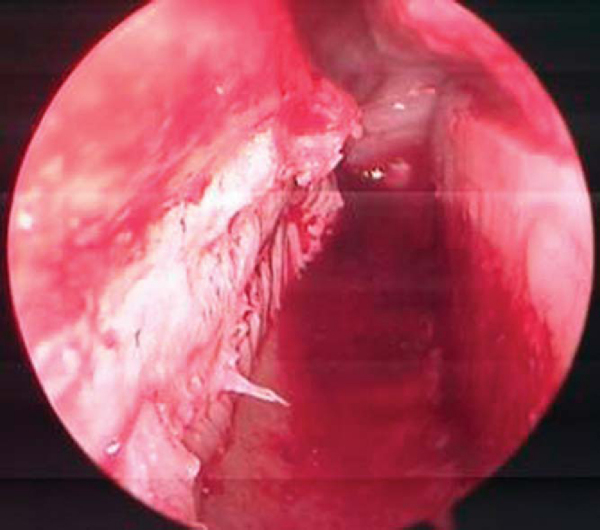

3. Arthrotomy with Graft Insertion

As with a standard meniscus repair by inside-out technique, a posteromedial or posterolateral incision is made to retrieve the meniscal sutures. A “reduction” suture is placed through the graft at the 10- or 2-o’clock position, passed into the joint, and retrieved. Proper placement of the reduction suture is important. When it is placed in the middle of the graft, it has a tendency to not bring the graft fully into the joint. With the suture retrieved, the meniscus is inserted into the channel and gently pushed inward while carefully pulling on the suture (

Fig. 48-11

). Extreme force should not be used because the sutures can be pulled through the graft and the bone bridge either fractured or inserted too far into the channel. Provided the channel and the graft bone are of proper size, a tamp can be used to assist in insertion. Care must be taken on insertion of the graft, for too forceful insertion may break out the posterior wall. Gentle tension on the reduction suture and application of an appropriate amount of varus or valgus stress on the knee aid in reduction of the meniscus (

Fig. 48-12

).

Once the graft is reduced, there is a tendency first to repair the anterior aspect of the graft under direct visualization before the arthrotomy is closed. However, to ensure anatomic position, the graft is initially secured with sutures in the posterior third and then the middle third of the graft. By proceeding in this manner, the anterior aspect is more forgiving in making adjustments in the graft position when the meniscus does not match perfectly.

Numerous methods can be used to secure the graft, but inside-out vertical mattress sutures are preferred because of greater strength. Either absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures can be used, for healing of the graft to the host readily occurs. Eight sutures are typically all that is needed (

Fig. 48-13

).

The wounds are closed, and dressing is applied by the treating surgeon’s preference. A postoperative brace is applied and initially locked in full extension.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction and Meniscal Allograft Transplantation

Tibial Osteotomy and Meniscal Allograft Transplantation

Tibial Osteotomy, Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction, and Meniscal Allograft Transplantation

| • | The initial postoperative visit is at 7 to 10 days with anteroposterior and lateral radiographs also obtained. | |

| • | Monthly visits are common until a stationary point is attained. |

| • | A brace is applied in full extension after the procedure. Range of motion is permitted once the patient is able to straight-leg raise. | |

| • | Partial weight bearing with the postoperative brace set at 0 to 90 degrees is permitted during the initial 4 weeks. | |

| • | Full weight bearing and unrestricted range of motion are permitted after 4 weeks. | |

| • | Progressive strengthening and functional training similar to ACL protocols are followed. | |

| • | Running is permitted at 12 weeks. | |

| • | Return to full activities is permitted at 4 months if strength is 80% or greater compared with the contralateral limb with normal functional testing. However, most patients do not achieve these goals until 5 to 6 months postoperatively. |

| • | Infection | |

| • | Arthrofibrosis | |

| • | Neurovascular injury during implantation | |

| • | Meniscus tear or incomplete healing | |

| • | Graft extrusion due to improper placement or size | |

| • | Loss of bone fixation or fracture |

Many studies have evaluated the use of meniscal allografts, with the initial group finding various outcomes. However, as the indications and surgical techniques have evolved, so has the rate of success. At present, most studies that follow the appropriate indications and operative methods report a success rate of 80% to 90%.

The number of published series regarding meniscal allografts are too numerous to list.

Table 48-1

summarizes several exemplary studies that have contributed to the progression of our current guidelines.

| Study | Followup (Mean) | Study Size | Clinical Results | Information Gained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garrett[3] (1993) | 2-7 years (unknown) | 43 patients | 35 of 43 (81%) successful | Grafts can reliably heal |

| 44 grafts | 20 of 28 intact at second-look arthroscopy | Advanced arthrosis results in failure | ||

| 8 failures related to arthrosis | ||||

| Noyes and Barber-Westin[4] (1995) | 22-58 months (30 months) | 82 patients | 58% of failed grafts were lyophilized, and majority of patients had advanced arthrosis | Arthritic knees and lyophilized grafts have high failure rates |

| 96 grafts | ||||

| Carter[1] (1999) | 24-73 months (35 months) | 46 patients | 45 patients had improvement in pain | Successful outcome with stringent patient selection |

| 46 grafts | 38 grafts were healed at second-look arthroscopy | Excellent healing to host | ||

| Rodeo[5] (2001) | Range unknown (2-year minimum) | 33 patients | 22 of 33 successful: 14 of 16 with bone fixation, 8 of 17 without bone | Bone fixation results are more favorable than when horns are not secured with bone |

| 33 grafts | ||||

| Wirth et al[9] (2002) | 12-15 years (14 years) | 22 patients | Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation: 6 deep-frozen, similar to normal meniscus; 17 lyophilized, similar to meniscectomy | Arthritis progression slowed with use of frozen grafts |

| 23 grafts | ||||

| van Arkel and de Boer[7] (2002) | 4-126 months (60 months) | 57 patients | Cumulative survival rate of 76%, 50%, and 67% for lateral, medial, and combined, respectively | Results deteriorate over time |

| 63 grafts | ||||

| Ryu et al[6] (2002) | 12-72 months (33 months) | 17 patients | 14/18 with grade III or lower: good–excellent | Results deteriorate as the grade of arthrosis is increased |

| 25 grafts | 3/7 grade IV: good–excellent | |||

| Verdonk et al[8] (2005) | 7.2 years (5-14.5 years) | 100 grafts | Cumulative survival of 74% medial and 70% lateral at 10 years | Results deteriorate with time Graft shrinkage can occur |

| 96 patients | ||||

| Cole et al[2] (2006) | 33.5 months (24-57 months) | 45 patients | 41 of 45 (91%) successful | High rate of success with strict indications |