CHAPTER 45 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 45 – Arthroscopic Meniscal Repair: Outside-In Technique

Scott A. Rodeo, MD

The anatomy, structure, blood supply, and function of the menisci are well understood. There is now strong evidence supporting the preservation of viable meniscal tissue in an otherwise intact knee.

All-inside, inside-out, and outside-in techniques are useful options for repair of meniscal tears. The outside-in technique was first described by Warren[14] as a method to decrease the risk of peroneal nerve injury during lateral meniscal repair. The choice of which technique is used is predominantly affected by the surgeon’s experience and the morphologic features of the tear. However, not all tears should be repaired, and surgical outcome for these repairs is determined by careful meniscal and patient selection.

Acute tears typically present with focal pain and mild swelling. Unstable meniscal tears may present with catching or locking. The patient usually recalls a twisting injury or deep flexion event. A longer history or history of antecedent pain, locking, swelling, or instability may indicate chronic meniscal disease.

Details of previous treatments and operative reports are helpful. Other factors to be considered are the age of the patient, the expected compliance of the patient with rehabilitation, and the patient’s physical ability to be non–weight bearing postoperatively.

Nonspecific important observations:

| • | Alignment: neutral, varus, or valgus | |

| • | Gait: is it antalgic? | |

| • | Loss of end range of motion: deep flexion and full extension | |

| • | Focal pain | |

| • | Painful clicking |

Signs supportive of meniscal tear:

| • | Magnetic resonance imaging |

Evaluate meniscal tear location (inner, middle, or outer third) and amount of abnormal meniscus, intrameniscal signal, articular cartilage, and cruciate ligament integrity. Increased intrameniscal signal indicates poorer healing potential.

Indications and Contraindications

When the history and preoperative imaging suggest that a meniscal tear may be amenable to repair, careful preoperative counseling of the patient is essential. The patient must be aware that postoperative restrictions are significant, and the patient’s compliance is key to a successful outcome.

The ideal candidate for an outside-in repair is a young, compliant patient with a short history of pain, a stable knee, and a vertical longitudinal tear in the red-red zone of a meniscus. Other specific indications include suturing of a meniscal replacement (allograft or replacement device, such as a collagen meniscus implant) and suturing of a Wrisberg-type discoid lateral meniscus in a small knee. Specific advantages are precise needle placement with reduced risk of chondral injury and relative ease of technique for anterior horn tears.

Relative contraindications for meniscal repair in general include degenerative flap or horizontal cleavage tears, partial-thickness tears, stable tears (<2 cm), tears in the white-white zone, and patients with an unstable or anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)–deficient knee. [5] [10] Radial tears, particularly in the posterior horn, are reparable where there is a rich blood supply. Better healing has been demonstrated with lateral meniscal tears, and therefore indications for lateral meniscal repair are broader. Small, vertical, longitudinal tears posterior to the popliteus tendon and small avulsion tears of the posterior horn in the setting of injury to the ACL may be observed.[3]

Other contraindications include far posterior tears (difficult to place sutures perpendicular to tear; use inside-out technique or all-inside), complex tears, older patients (older than 50 years), and chronic tears with deformation of the meniscus.

The decision regarding type of anesthesia is generally made between the anesthesiologist and the patient. Spinal anesthesia is effective for outpatient knee arthroscopy surgery and meniscal repair work. Femoral nerve blocks, although helpful, can potentially delay rehabilitation and return of quadriceps function.

Standard setup includes a thigh tourniquet and a lateral post. The limb should be placed on the operating table in such a position that when the end of the table is flexed, the end of the thigh protrudes over the table break. This provides access to the posteromedial and posterolateral corners of the knee.

Surgical Landmarks, Incisions, and Portals

| • | Patella | |

| • | Patellar tendon | |

| • | Joint line–plateau: mark with surgical marker | |

| • | Fibular head, biceps tendon |

Use a standard anterolateral portal for initial arthroscopy. Determine the best anteromedial portal after spinal needle confirmation of correct height and location. Portal location is less important in this type of repair, whereas instrument trajectory is crucial in all-inside and inside-out repairs. For the lateral meniscus, use the high anteromedial portal.

The large posterior incisions are not necessary in performing the outside-in repair. However, it is difficult to place perpendicular sutures for far posterior tears, and oblique suture orientation compromises fixation stability.[13] In performing the dissection down to capsule for needles introduced posteromedially or posterolaterally, consider underlying superficial structures:

| • | Posteromedial: saphenous nerve, medial collateral ligament | |

| • | Posterolateral: peroneal nerve, lateral collateral ligament |

Examination of range of motion and stability is performed before sterile preparation and draping of the lower extremity.

| • | Joint surfaces | |

| • | ACL | |

| • | Location, orientation, and stability of tear. Visualization of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus is facilitated by inserting the arthroscope through the anterolateral portal and passing it between the posterior cruciate ligament and the medial femoral condyle. | |

| • | Abrade surfaces of tear to make a bleeding bed with a rasp or 3.5-mm full-radius resector.[2] Consider the posteromedial portal for this purpose. Flex knee, palpate pes anserinus tendons, and introduce spinal needle anterior to these. The portal incision is posterior and proximal to the medial joint line. | |

| • | Abrade synovial membrane adjacent to tear to stimulate additional vascularity.[9] |

Specific Steps (

Box 45-1

)

| • | 18-gauge spinal needles | |

| • | Arthroscopic grasper | |

| • | Suture: rigid, monofilament; No. 0 polydioxanone (PDS) |

| Surgical Steps | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Prepare the meniscus by gentle débridement or abrasion of the edges of the tear and the synovial fringe that appears on the superior and inferior surface of the capsule. Use a rasp or 3.5-mm full-radius resector.

2. Locate Skin Surface over Meniscal Tear

Locate the skin surface over the meniscal tear by use of topographic landmarks, palpation, and transillumination. Transillumination minimizes injury to cutaneous nerves and vessels.

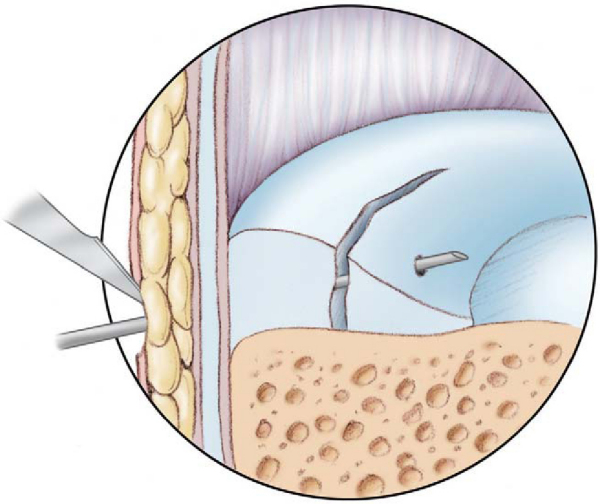

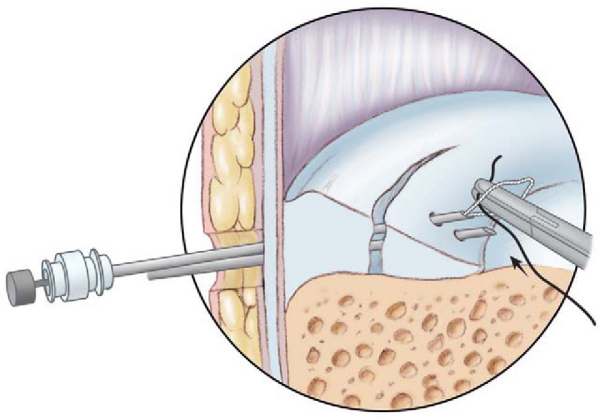

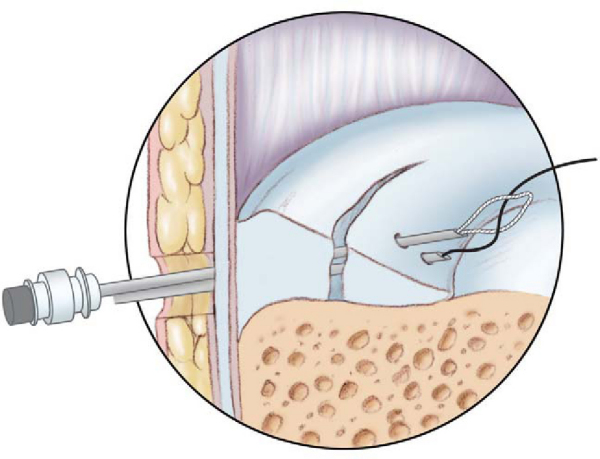

Pass one spinal needle through the skin, subcutaneous tissue, capsule, and outer edge of the meniscus across the tear and through the inner meniscus (

Fig. 45-1

). The needle can exit either the superior (femoral) or inferior (tibial) surface of the meniscus. A probe or small loop curet may be used to control needle position or to provide counterpressure on the meniscus while the needle is being passed. Do not pass through the inner rim of the meniscus; this is thin tissue that will tear or fold when sutures are tensioned. Consider curved needles for posterior tears.

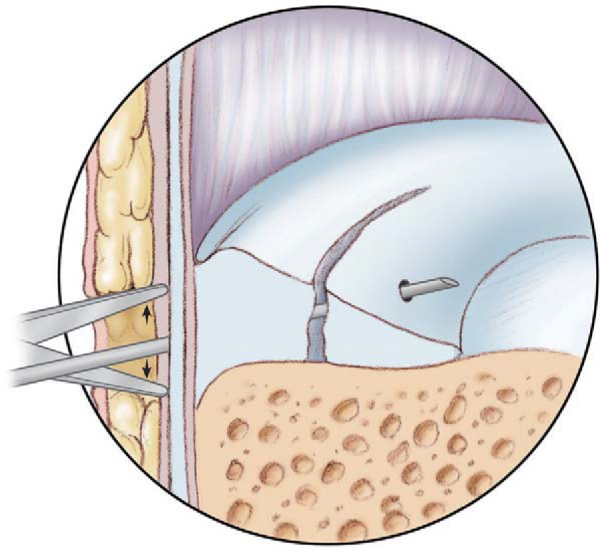

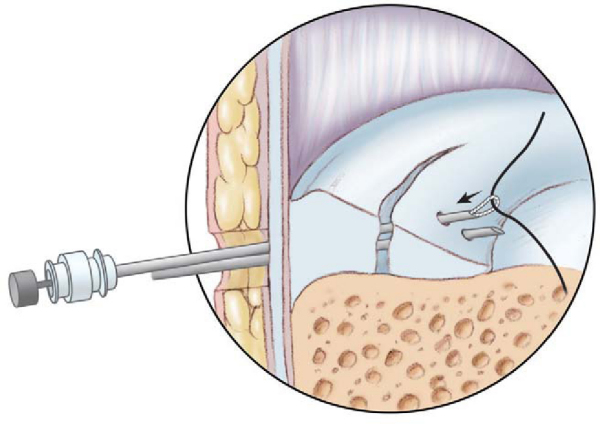

4. Make Small Skin Incision Around Needle

Make a small skin incision around the needle and spread the subcutaneous tissue down to the capsule (

Fig. 45-2

). Be careful to consider the saphenous nerve on the medial side.

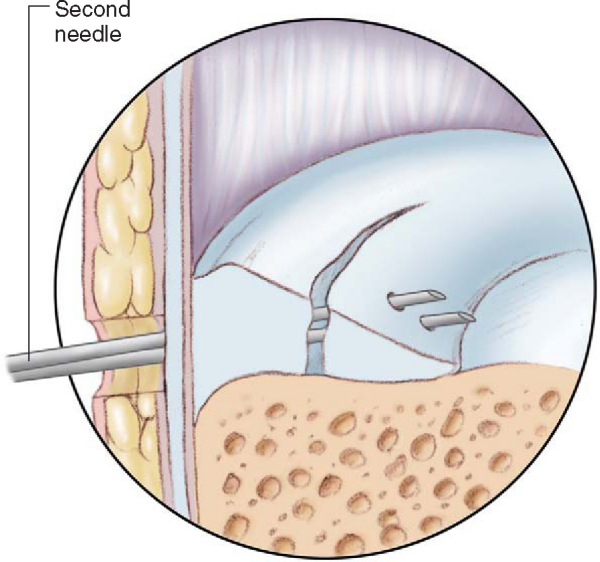

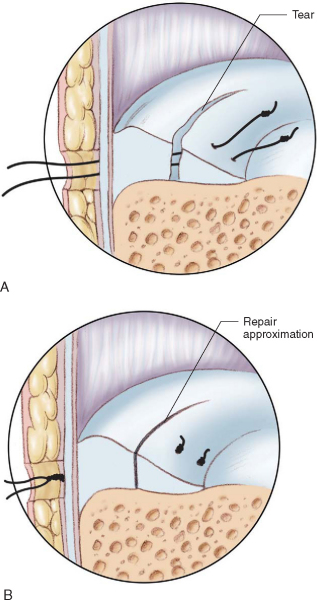

Pass the second spinal needle through this incision from outside-in, emerging from the meniscus adjacent to (∼5 mm) the first needle (

Fig. 45-3

). Needle placement dictates suture orientation (vertical or horizontal mattress). The vertical mattress configuration shows the least displacement under load.[8] Consider alternating femoral and tibial surface sutures.

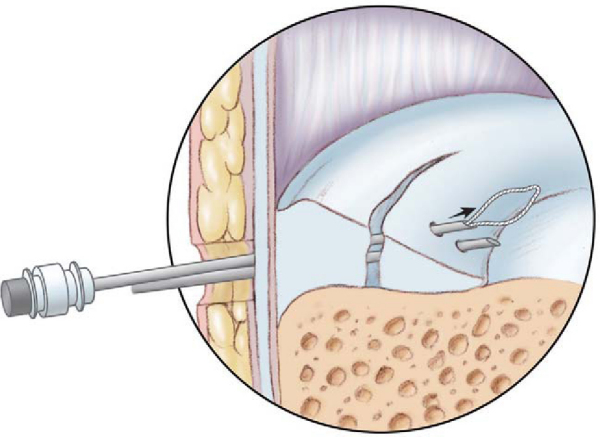

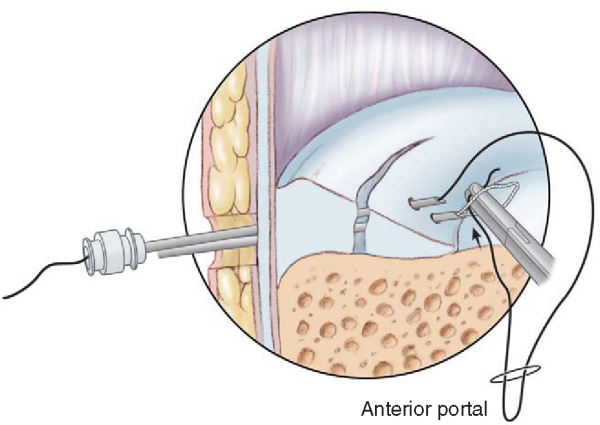

Use a working cannula through the anteromedial portal. Most graspers and instruments can be used through a 7-mm portal. Four options for securing sutures are as follows.

1. Cable Loop Pull-through Technique (Johnson[4])

Pass cable loop through one needle (

Fig. 45-4

). Place absorbable suture with grasper through anterior portal into wire loop (

Fig. 45-5

). Pull suture through meniscus (

Fig. 45-6

). Repeat steps with other end of suture and other needle (

Fig. 45-7

). Withdraw needles and tie the single suture subcutaneously over the capsule (

Fig. 45-8

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 45-5 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 45-7 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 45-8 |

If a cable loop is not available, the No. 0 PDS suture can be passed through the spinal needle out through the anteromedial portal, where a permanent suture can be tied to the PDS. The knot is then pulled through the meniscus. The process is repeated, resulting in a mattress suture.[16]

2. Cable Loop Capture Technique (Cooper[1])

Place suture through one needle. Pass wire cable loop through other needle and capture end of suture material in joint (

Fig. 45-9

). Pull suture end out through meniscus and tie subcutaneously over capsule.

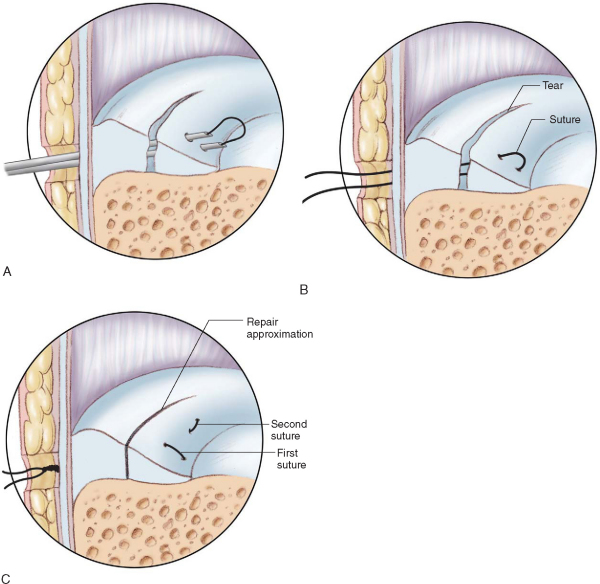

3. Mulberry Knot Technique (Warren[15])

Pass suture (No. 0 PDS) into needle, grasp inside joint, and pull out through anterior portal. Pass second suture (No. 0 PDS) into adjacent needle and repeat procedure.

Tie a knot (three or four throws) in the end of each suture, then pull knot back into joint so that knots lie against meniscus and maintain tear in reduced position. Use a cannula in the anterior portal to avoid entrapment of the knot in soft tissues. Tie adjacent sutures together over capsule (

Fig. 45-10

).

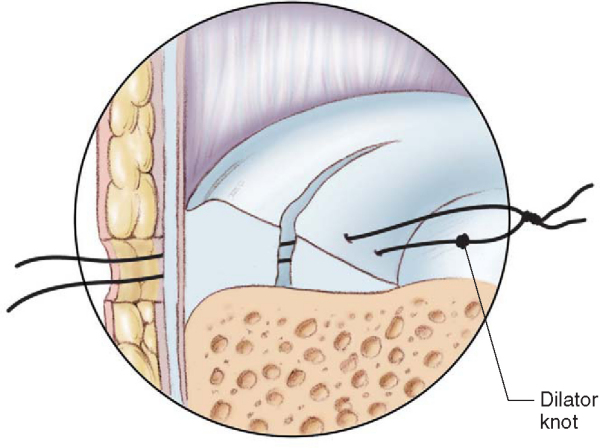

4. Dilator Knot Technique (Cooper[1])

Pass suture (No. 0 PDS) into needle, grasp inside joint, and pull out through anterior portal. Pass second suture (No. 0 PDS) into adjacent needle and repeat procedure. Use a cannula in the anterior portal to avoid entrapment of soft tissues between the sutures.

Tie a small knot (two throws) in one suture. Then tie adjacent sutures together outside portal. Pull suture with smaller knot (dilator knot) through meniscus (inside-out) ahead of the knot holding the two sutures together (

Fig. 45-11

). Now you can tie the single suture subcutaneously over the capsule.

Supplementary options to provide access to marrow-derived cells or factors are fibrin clot insertion[12] and microfracture in the notch.

Technical Considerations and Complications

Clinical studies demonstrate good results with accelerated rehabilitation[6]; however, few studies have used objective evaluation of meniscus healing (arthroscopy, magnetic resonance imaging). It is known that a tear may be only partially healed yet asymptomatic.[13] The long-term fate of such tears is unknown. Consider tailoring the postoperative protocol on the basis of the type of meniscal tear.

| • | Use transillumination | |

| • | Blunt dissection down to capsule |

| • | Poor selection | |

| • | Poor technique | |

| • | Oblique suture orientation | |

| • | Inadequate protection of repair | |

| • | Instability of knee | |

| • | Reinjury |

Results of meniscal repair by the outside-in technique are shown in

Table 45-1

.

| Author | No. of Repairs | Evaluation | Followup | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morgan et al[7] (1991) | 74 (of 353 repaired menisci) | Second-look arthroscopy | 84% successful outcome (62/74) 65% healed (48/74) 19% partially healed (14/74) 16% failure rate (12/74) |

|

| Increased failure in ACL-deficient knees and posterior horn tears of medial meniscus | ||||

| Rodeo and Warren[11] (1996) | 90 | Computed tomographic arthrography | Minimum of 2 years | 86% successful outcome (partial or complete healing with minimum symptoms) |

| Increased failure in unstable knees | ||||

| van Trommel et al[13] (1998) | 51 | Arthroscopy, arthrography, magnetic resonance imaging, or combination | Average of 15 months (range: 3-80) | 45% complete healing |

| 32% partial healing | ||||

| 24% no healing | ||||

| Significantly lower healing for tears in posterior horn of medial meniscus |

In the Hospital for Special Surgery experience,[11] an 86% successful outcome was reported: 67% asymptomatic with objective evidence for complete healing, 19% minimally symptomatic with objective evidence for partial healing, and 14% failure rate (significant symptoms or objective evidence of failure to heal). The failure rate was based on knee stability: stable knees, 15% (5 of 33); unstable knees, 38% (5 of 13); and concomitant ACL reconstruction, 5% (2 of 38). Fibrin clot was used in 17 repairs with a failure rate of 35% (6 of 17) due to unrepaired ACL insufficiency (3) and complex tears in the avascular zone of the meniscus (3). Complications (3%) included saphenous nerve entrapment (1), thrombophlebitis (1), and infection (1).

In the study of Morgan et al,[7] the majority of failures occurred in posterior horn tears of the medial meniscus (11 of 12 failures), and all failures occurred in ACL-deficient knees. Healing was complete with disappearance of the absorbable suture in approximately 4 months. These authors were among the first to point out that incompletely healed menisci can be clinically asymptomatic.

van Trommel et al[13] described different regional healing rates with the outside-in technique. A significantly lower healing rate was reported for tears in the posterior horn of the medial meniscus, which was thought to be due to the obliquity of the sutures in this region. It can be difficult to place the needles perpendicular to the tear in the far posterior zone of the meniscus, resulting in oblique suture placement. The inside-out or all-inside technique should be considered for repair of tears in the posterior horn of the medial meniscus.