CHAPTER 44 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 44 – Arthroscopic Meniscus Repair: Inside-Out Technique

Warren R. Kadrmas, MD

The meniscus functions to evenly distribute and transmit loads within the knee and provides secondary stability to tibial translation on the femur. Although Annandale[2] reported the first meniscus repair in 1885, it was nearly a century later that the practice of meniscal preservation became the standard. Fairbank[10] was the first to indirectly question the practice of complete meniscectomy and described the degenerative changes that result from its functional loss. Open repair, as popularized by DeHaven, [7] [8] was initially developed in an attempt to preserve meniscal function. The introduction of arthroscopic surgery soon led Henning[15] to advocate a combined arthroscopic and open technique, which involves small posteromedial and posterolateral incisions to receive sutures that are placed from within the joint. Many additional techniques have been described to repair the meniscus. [5] [16] However, the inside-out arthroscopically assisted technique is widely held as the standard with which other repair techniques are compared.

It is critical to obtain a detailed history, including the mechanism of injury, associated injuries, date of injury, and previous treatments that may have been rendered. The patient’s presenting symptoms and expectations of outcome should be addressed at the initial visit. If surgical intervention has been attempted previously, it is important to obtain the operative reports as well as intraoperative photographs if they are available.

Magnetic resonance imaging allows the determination of the location and orientation of the tear as well as full evaluation of associated ligamentous and chondral injury.

Indications and Contraindications

Many factors contribute to the success of meniscal repair. The ideal candidate is a young (younger than 45 years), active patient with a traumatic vertical tear at the meniscosynovial junction. Location of the tear has been shown to be the most important predictor of success. [9] [17] Historically, repair has been indicated for tears in the peripheral, vascular portion of the meniscus as described by Arnoczky and Warren.[4] However, reports have documented successful repair of tears in the avascular zone in young patients. [13] [14] Complex and chronic tears have a lower success rate after repair. [9] [17] Meniscal tears that are not suitable for repair are degenerative in nature and involve moderate to severe damage to the meniscal body fragment. Repair is generally not recommended in elderly, less active individuals or in those unable to comply with the postoperative rehabilitation regimen.

Meniscal repair may be performed by general, regional, or spinal anesthesia on the basis of the patient’s, anesthesiologist’s, and surgeon’s preferences. The patient is placed supine on a standard operating room table, and a thigh tourniquet is applied. The patient should be positioned with the knee distal to the break in the bed to allow full flexion of the knee, and a leg holder or lateral post is applied. Circumferential access to the knee is required for posterolateral or posteromedial approaches for meniscal suturing.

Surgical Landmarks, Incisions, and Portals

| • | Patellar tendon | |

| • | Tibial plateau | |

| • | Fibular head | |

| • | Medial-lateral joint line |

| • | Inferomedial portal | |

| • | Inferolateral portal | |

| • | Additional outflow portal as needed (superolateral or superomedial) |

| • | Posterolateral approach | |

| • | Posteromedial approach |

Examination Under Anesthesia and Diagnostic Arthroscopy

Examination under anesthesia is performed to evaluate range of motion as well as associated ligamentous stability. Complete diagnostic arthroscopy is always performed before any meniscal pathologic process is addressed. Injuries to the chondral surfaces or intraarticular ligaments may need to be addressed in conjunction with the meniscal repair.

Specific Steps (

Box 44-1

)

The diagnostic arthroscopy portion of any case is always the same. The patient is placed supine on the operating table, and a tourniquet is applied to the upper thigh. Arthroscopy is performed with a lateral post or a leg holder on the basis of the surgeon’s preference. An initial inferolateral portal is made adjacent to the patellar tendon, and the arthroscope is inserted. A complete arthroscopy is performed to visualize the knee and to identify any pathologic change that has not been found on plain film or magnetic resonance imaging. This also provides direct examination of the menisci and allows final assessment of the reparability of the tear. Additional pathologic changes within the knee may need to be addressed in conjunction with the meniscal repair.

| Surgical Steps | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Correct placement of the inferomedial portal is critical in addressing a meniscal tear. The location of the portal can be visualized directly by insertion of a spinal needle medial to the patellar tendon. The spinal needle should enter the medial compartment superior to the medial meniscus and parallel to the tibial plateau. The location of the portal needs to be customized on the basis of the location of the tear. To have access to the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus, for example, the portal may need to be placed slightly more proximal and immediately adjacent to the patellar tendon for access to be gained above the tibial spines. An arthroscopic probe is then placed within the working portal, and the meniscal tear is evaluated for its reparability.

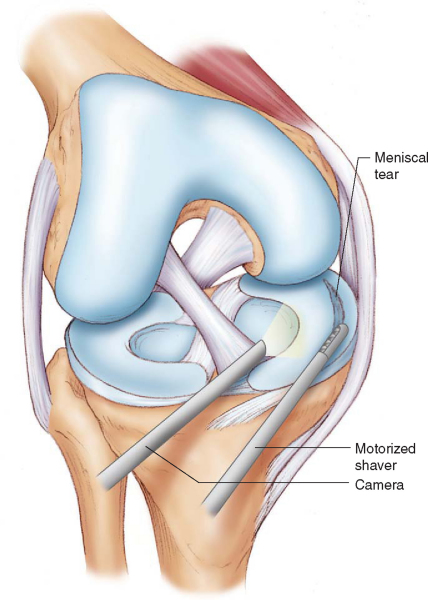

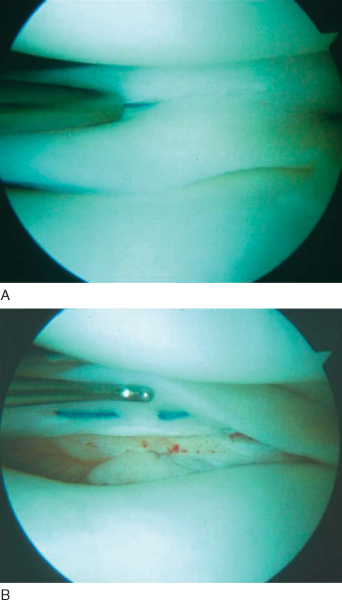

Once the tear has been deemed appropriate for repair, it is prepared with a hand-held rasp or mechanical shaver to stimulate bleeding within the tear (

Fig. 44-1

). An arthroscopic probe may be pressed against the capsule at the junction of the middle and posterior portions of the meniscus to facilitate accurate placement of the posteromedial or posterolateral incision. The tip of the probe can usually be palpated at the posterior aspect of the joint line before an incision is made.

|

|

|

|

Figure 44-1 |

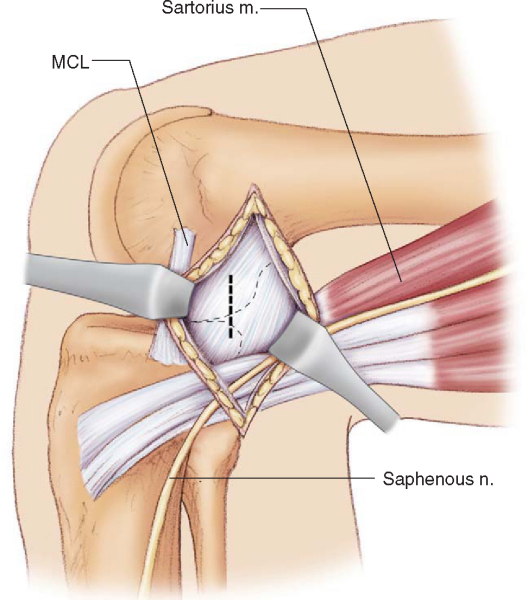

A vertical 3- to 4-cm incision is made over the posteromedial joint line centered over the palpated arthroscopic probe with the knee flexed 60 to 90 degrees. The incision is carried through the skin, and Metzenbaum scissors are used to dissect the subcutaneous tissues. Care must be taken to protect the greater saphenous nerve, which generally lies posterior to the skin incision. Dissection continues to the level of the pes fascia, which can be identified by its obliquely oriented fibers. The fascia is incised sharply with a scalpel at the superior margin of the sartorius, and blunt dissection is performed with the surgeon’s finger (

Fig. 44-2

). The posteromedial capsule can easily be palpated at the depth of the incision and a popliteal retractor placed at its posterior margin. The popliteal retractor separates the posteromedial capsule laterally from the saphenous nerve and pes tendons medially.

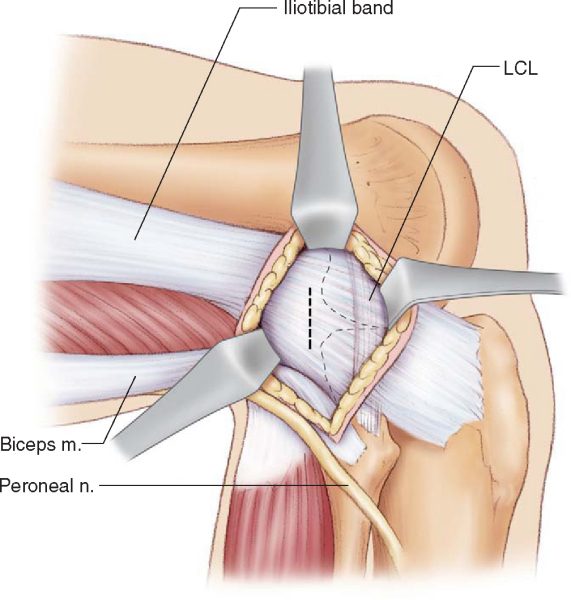

With the knee flexed 90 degrees, a vertical 3- to 4-cm incision is made over the posterolateral joint line centered over the palpated arthroscopic probe. Dissection is carried through the skin, and Metzenbaum scissors are used to dissect the subcutaneous tissues. The interval between the iliotibial band and the biceps tendon is identified and sharply incised with a scalpel. The biceps tendon is retracted posteriorly and serves to protect the peroneal nerve. Blunt dissection with the surgeon’s finger allows direct palpation of the posterolateral capsule and the lateral head of the gastrocnemius at the depth of the incision (

Fig. 44-3

). A popliteal retractor is placed at the posterior margin of the capsule and separates the posterolateral capsule medially from the lateral head of the gastrocnemius laterally. The remainder of the lateral meniscal repair is usually performed in the figure-of-four position.

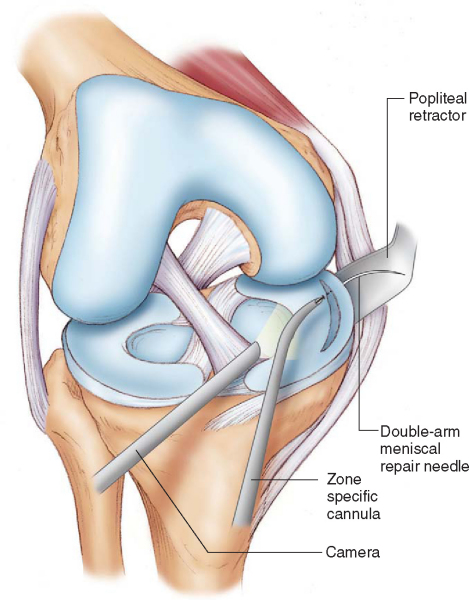

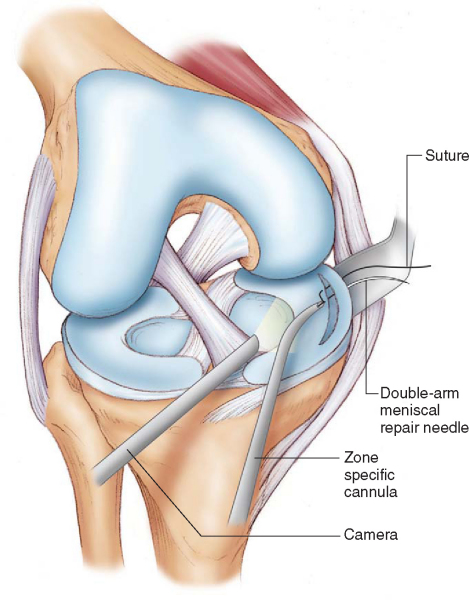

The meniscal body fragment is reduced with a probe in preparation for suture repair. We prefer to use a curved, zone-specific cannula system, although many varieties of suture repair systems are widely available. The arthroscope remains in the ipsilateral portal for viewing; the contralateral portal is used for suture placement in the anterior and central horns of the meniscus during repair. Viewing and working portals may need to be switched for placement of posterior horn sutures. Suture placement begins at the posterior extent of the identified tear and gradually extends to the anterior margin. Double-arm meniscal repair needles are delivered into the joint and guided into position with the zone-specific cannula system. The curve of the cannula should be directed medially for a medial meniscus tear and laterally for a lateral meniscus tear to facilitate exit into the popliteal retractor. A single limb of the suture is initially passed through the meniscus and retrieved by a surgical assistant as it exits within the popliteal retractor (

Fig. 44-4

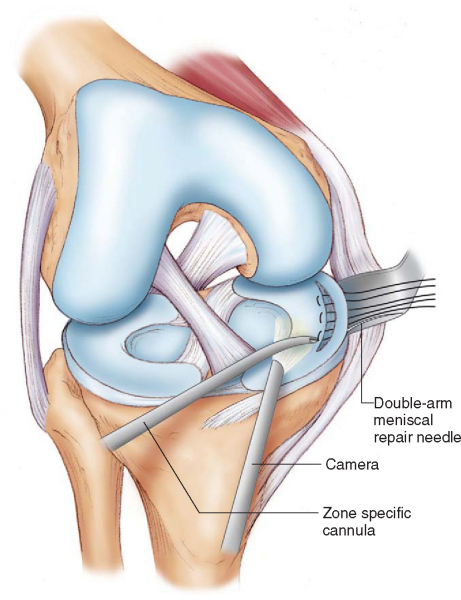

). The remaining limb of the suture is placed in a similar manner to form a mattress stitch, and the pair are held with a clamp to facilitate suture management (

Fig. 44-5

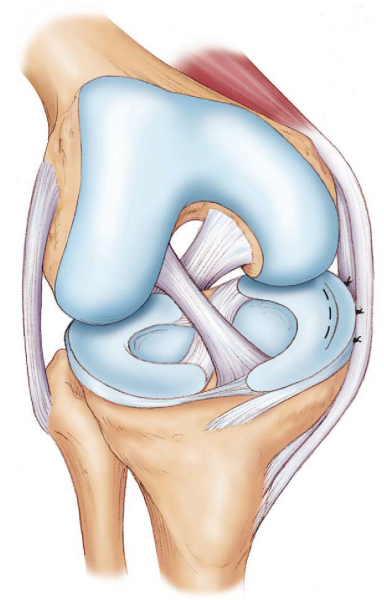

). Sutures are placed sequentially from posterior to anterior until the full extent of the tear is addressed (

Fig. 44-6

). Sutures are placed at 3- to 5-mm intervals and may alternate on the superior and inferior surface of the meniscus (

Fig. 44-7

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 44-4 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 44-5 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 44-6 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 44-7 |

The sutures are serially tied from posterior to anterior against the capsule with care not to overtighten or to deform the meniscal body (

Fig. 44-8

). A fibrin clot may be placed within the meniscal tear, particularly for those tears that extend to the avascular zone (e.g., complete radial tear in a young patient), before the sutures are tied. The knee is taken through a full range of motion and visualized for gap formation or suture breakage.

|

|

|

|

Figure 44-8 |

The arthroscopic portals are closed in the standard fashion, and the accessory wound is closed in layers.

| • | Infection | |

| • | Arthrofibrosis | |

| • | Failure of meniscus to heal | |

| • | Nerve injury (saphenous medially, peroneal laterally) | |

| • | Vascular injury (popliteal fossa) |

After meniscal repair, good to excellent results can be expected in approximately 85% of patients (

Table 44-1

). Results are greatest for traumatic vertical tears in young patients who undergo concomitant anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. However, excellent results have also been reported for isolated meniscal repairs as well as for complex tears extending to the avascular portion of the meniscus.

| Author | No. of Repairs | Criteria | Followup | Concomitant ACL Tear | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johnson et al[11] (1999) | 38 | Clinical | 10 years, 9 months (average) | None | 76% successful |

| Cannon and Vittori[6] (1992) | 90 | Arthroscopy or arthrography | 7 months (mean): isolated repairs 10 months (mean): concurrent ACL reconstructions |

68 ACL tears (76%) All reconstructed |

93% success with ACL reconstruction 50% success of isolated repair |

| Miller[12] (1988) | 79 | Arthroscopy or arthrography | 3.25 years (mean) | 68 reconstructions 22 stable ACL |

93% healed with ACL reconstruction 84% healed with isolated meniscal repair |

| Tenuta and Arciero[17] (1994) | 54 | Clinical and arthroscopy | 11 months (mean) | 40 reconstructions 14 stable ACL |

Arthroscopy 90% healed with ACL reconstruction 57% healed with isolated meniscal repair Better with rim width <4 mm, age <30 years |

| Rubman et al[14] (1998) | 198 | Clinical ± arthroscopy | Clinical examination: 42 months (23-116) 180 meniscal repairs (91%) in 160 patients Arthroscopy: 18 months (2-81) 91 meniscal repairs (46%) in 79 patients |

128 ACL tears (72%) 126 reconstructed 96 concurrent 30 delayed |

80% asymptomatic (clinically) 20% (39) repeated arthroscopy for symptoms 2 (5%) healed 13 (33%) partially healed 24 (62%) failed Arthroscopy (91 repairs) 23 (25%) completely healed 35 (38%) partially healed 33 (36%) failed |

| Eggli et al[9] (1995) | 54 | Clinical ± magnetic resonance imaging | 7.5 years (average) | None | 73% success 64% of failures in first 6 months Better with acute injury (<8 weeks), age <30 years, tear length <2.5 cm Worse with rim width >3 mm, absorbable sutures |

| Albrecht-Olsen and Bak[1] (1993) | 27 | 3 clinical | 3 years (median) | None | 63% success |