CHAPTER 29 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 29 – Management of Pectoralis Major Muscle Injuries

Jon K. Sekiya, MD

First described in 1822 by Patissier, pectoralis major ruptures are an uncommon injury. During the past 30 years, small case series have increased awareness of this injury, and meta-analyses of these studies have shown that operative repair results in significantly better outcomes than nonoperative treatment. [1] [2] The pectoralis major consists of two muscle heads that converge and insert lateral to the bicipital groove as two distinct laminae. [8] [16] The inferior sternocostal head fibers rotate and insert posterior and superior to the clavicular fibers, placing them at a mechanical disadvantage at the extremes of humeral extension.[16] Ruptures can be classified as complete or incomplete and may occur as avulsions from the humerus or rupture of the tendon, musculotendinous junction, or muscle belly. [1] [7] [8] [10]

Techniques for repair include sutures through drill holes in the humerus, barbed staples, and suture anchors. [1] [2] [6] [8] [11] [14] [16] The senior author prefers the use of a bone trough with tunnels to reapproximate the laminae to their native insertions.

Given the relative rarity of pectoralis major ruptures, knowledge of their mechanism and physical findings is essential to ensure timely and accurate diagnosis of this injury. In a series by Hanna et al,[7] 50% of unrepaired ruptures were initially misdiagnosed or diagnosed late. Peak incidence of this injury occurs in male athletes between 20 and 40 years old. [1] [2] [8] Indirect injury mechanisms are most common, although rupture has been reported with direct blows and trauma. [2] [8] [16] Bench press is the most common activity associated with pectoralis major ruptures. Eccentric contraction with the arm abducted and externally rotated places the inferior fibers of the sternocostal head at a mechanical disadvantage and results in their failure first.[16]

Patients report a tearing or searing pain often associated with a “pop” when the injury occurs. This is usually accompanied by the acute onset of swelling, ecchymosis, and painful motion of the affected arm. Patients may not seek treatment immediately but will usually present with continued weakness, pain with movement of the arm, and deformity with muscle contraction.

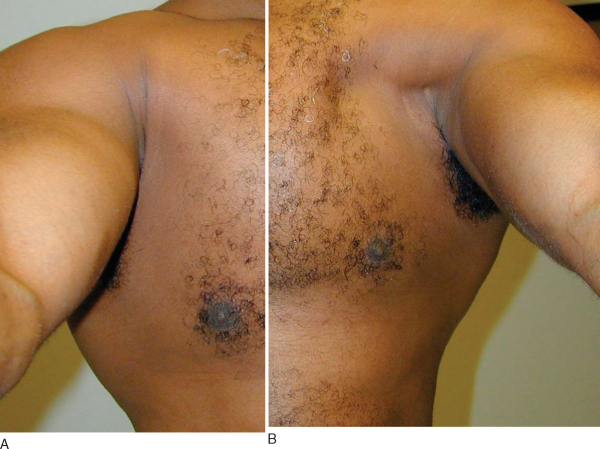

Ecchymosis is usually present over the anterior chest, axilla, or proximal arm of the injured patient. The anterior chest and axilla are examined for asymmetry with the contralateral side. Loss of chest wall contour can be accentuated by abducting the arm 90 degrees or having the patient adduct against resistance (

Fig. 29-1

). A cord of remaining fascia may still be present on the lateral chest wall and may be mistaken for an intact pectoralis major tendon. This cord represents the intact fascia of the pectoralis major and its continuation with the fascia of the brachium and medial antebrachial septum. Direct palpation of the axilla will often reveal a defect, particularly in the inferior lateral aspect of the chest wall just at the medial border of the axilla. However, this can be masked by the intact fascia, hematoma or edema, or intact clavicular head of the pectoralis major. Serial examinations may be necessary during a short period, but the diagnosis of a pectoralis major rupture is usually made clinically.

|

|

|

|

Figure 29-1 |

Plain radiographs of the injured shoulder are obtained to evaluate for associated fractures or possible bone avulsions; however, no gross abnormalities are usually appreciated.[15] Other studies described Cybex testing, ultrasonography, and computed tomographic evaluation, but magnetic resonance imaging is the optimal imaging technique for delineation of pectoralis major injuries. [4] [5] [9] [11] [12] [13] T2-weighted axial images are most helpful in evaluating acute injuries, and magnetic resonance imaging may help distinguish between complete, partial, and intramuscular ruptures.[12] In cases with equivocal physical examination findings, magnetic resonance imaging may prevent a delay in diagnosis.[11]

Indications and Contraindications

Nonoperative treatment may be pursued for intrasubstance muscle tears of the pectoralis major or in elderly patients.[3] Complete tears of the pectoralis major, including isolated tears of the sternocostal head, should be treated surgically in young, healthy patients. Residual deformity and weakness will remain in such tears treated nonoperatively. [8] [10] [14]

General anesthesia is preferred to allow complete muscle relaxation and mobilization of the torn pectoralis major tendon. The patient is placed in the modified beach chair position with the head and body elevated approximately 30 to 45 degrees. A sandbag or small roll of sheets may be placed under the patient’s scapula to allow more motion of the shoulder during repair. The arm and shoulder are prepared and draped free to allow intraoperative manipulation and positioning.

Standard landmarks for a deltopectoral approach are used. The proximal extent of the incision may be placed slightly medially for better mobilization of the often retracted pectoralis tendon and muscle. The distal portion of the incision may be placed slightly laterally on the arm to allow easier access to the humeral insertion during repair.

An evaluation under anesthesia of the affected shoulder is performed with attention directed to the anterior chest wall and axilla. Comparison to the contralateral side is made, and deformity or defects are noted.

Specific Steps (

Box 29-1

)

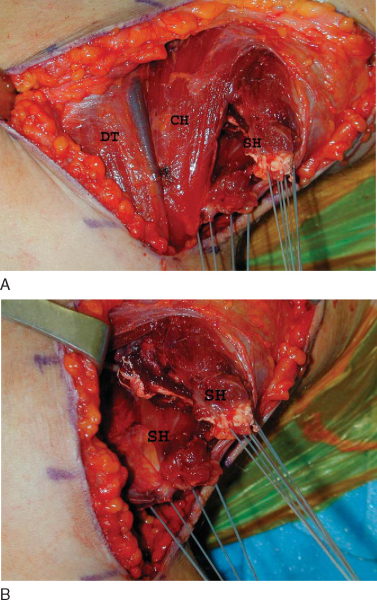

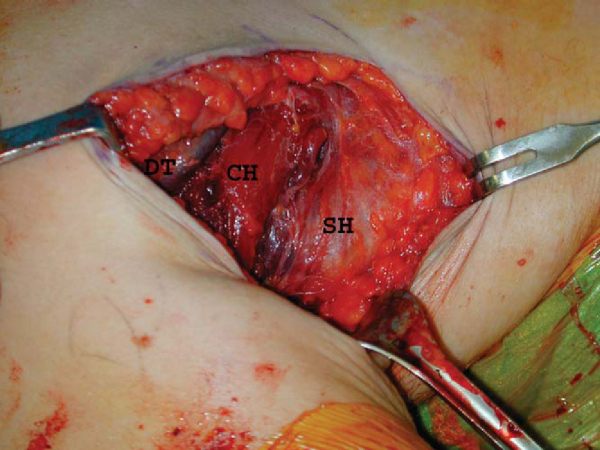

A standard longitudinal incision is made for a deltopectoral approach. Once the incision is made through the skin, hemostasis is obtained, and subcutaneous dissection is performed to identify and free the pectoralis major from the subcutaneous tissues. The interval between the pectoralis and deltoid is identified, and the cephalic vein is mobilized and protected as this interval is developed. The retracted end of the torn pectoralis is often identified medially in the wound where it has retracted. In the case of an isolated rupture of the sternocostal head, this is identified inferior to the intact clavicular head of the pectoralis major (

Fig. 29-2

).

| Surgical Steps | ||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 29-2 |

The end of the torn tendon may be grasped and a temporary suture placed to allow traction of the muscle during mobilization. A combination of sharp and blunt dissection is used to free the muscle and tendon from both the chest wall and subcutaneous tissues. The difficult dissection encountered in chronic tears is facilitated by anesthesia, providing complete muscle relaxation during dissection. Once the tendon is mobilized, a double laminar repair is performed with a No. 2 or No. 5 braided nonabsorbable suture. A Krackow stitch is used to place two or three sutures in the lamina of the sternocostal and clavicular heads, with up to six sutures total (

Fig. 29-3

). In the case of an intrasubstance muscle tear, a three-layered, modified Kessler technique is used to reapproximate the posterior fascia, middle muscle, and anterior fascia.

|

|

|

|

Figure 29-3 |

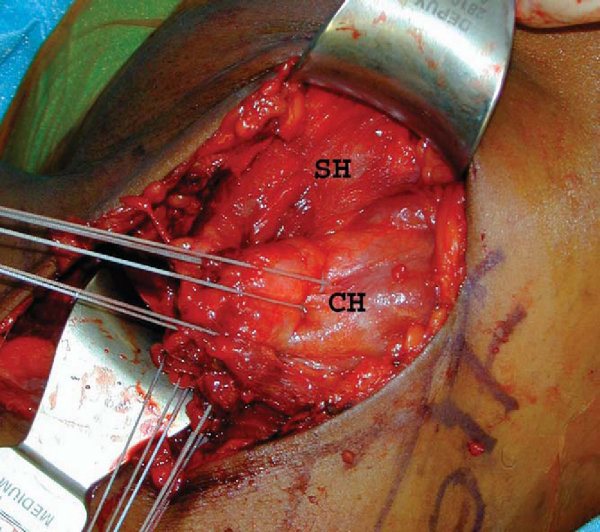

Once the tendon has been mobilized and sutures have been placed, the insertion site is identified and prepared for reattachment. The insertion of the pectoralis major tendon is located just lateral to the bicipital groove. A retractor holds the deltoid and cephalic vein out of the field. The biceps tendon is identified on the anterior humerus, and a longitudinal incision in the periosteum is made directly lateral to this. In the case of an isolated sternocostal head rupture, the intact lamina of the clavicular head will need to be retracted cephalad and lateral to allow placement of the sternocostal head just medially. A trough is made with a bur lateral to the biceps groove for insertion of the tendon, with care taken not to breach the cortex fully. A bur or drill is then used to make three holes in the cortex approximately 10 mm apart in a longitudinal manner along this trough. Matching holes are made approximately 5 mm more lateral to the first holes to allow tying of the sutures over a bone bridge (

Fig. 29-4

). Internal and external rotation of the humerus will aid in exposure and access for placement of these holes.

|

|

|

|

Figure 29-4 |

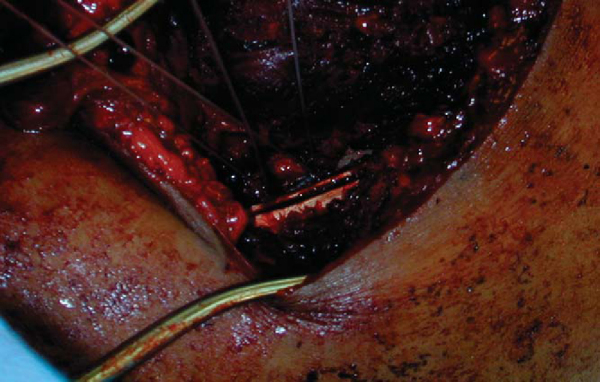

A needle or suture passer is then used to place each paired suture strand through separate holes, and these sutures are tied over the bone bridges with the arm placed in neutral adduction and rotation. The repair is visually inspected and palpated while the arm is gently internally and externally rotated to ensure coordinated movement of the pectoralis muscle and tight reapproximation to its insertion site (

Fig. 29-5

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 29-5 |

A standard closure is performed with reapproximation of the subcutaneous tissue followed by skin closure of the surgeon’s choice. We prefer a subcuticular closure with absorbable suture for optimal cosmesis.

The patient is placed in a sling on the operative side, and physical therapy is initiated on postoperative day 1 for pendulum exercises. Only passive motion consisting of passive forward elevation of the adducted arm to 130 degrees is allowed for the first 6 weeks. The patient is instructed to avoid any active forward elevation or abduction during these 6 weeks. After 6 weeks, passive range of motion is advanced, and a periscapular strengthening regimen is begun to include isometric exercises. The patient is monitored and at 3 months should have full motion of the affected shoulder. The strengthening regimen is then advanced, and at 6 months the patient may resume lightweight press exercises and pushups. Full activity is allowed approximately between 9 and 12 months. Single-rep maximum bench pressing is discouraged indefinitely.

Proper tensioning of the repair is necessary to avoid stiffness or residual weakness of the pectoralis major. Neutral positioning of the arm helps reduce the risk of inappropriate tensioning. The risk of complications increases in chronic injuries as a result of increased difficulty with surgical exposure secondary to increased retraction and scarring of the ruptured tendon.[2]

Because of the relative rarity of pectoralis major tears, outcome studies are limited to small case series and meta-analyses. Overall surgical outcomes are better than nonsurgical treatment in both acute and chronic tears (

Fig. 29-6

and

Table 29-1

|

|

|

|

Figure 29-6 |

| Author | Study | Results | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aarimaa et al[1] (2004) | 33 repairs | 33 repairs: 13 excellent, 17 good, 3 fair | ||||||||

| Metaanalysis of 73 cases | Metaanalysis of 73 cases

|

|||||||||

| Hanna et al[7] (2001) | 22 ruptures | 10 repaired: peak torque 99% of uninjured side | ||||||||

| 12 nonoperative: peak torque 56% of uninjured side | ||||||||||

| Bak et al[2] (2000) | Metaanalysis of 72 cases | Surgical repair: 88% excellent-good (statistically better if repaired within 8 weeks of injury) | ||||||||

| Nonoperative: 27% excellent-good | ||||||||||

| Schepsis et al[14] (2000) | 17 ruptures | 6 acute repairs (<2 weeks from injury): 96% subjective, 102% isokinetic strength | ||||||||

| 7 chronic repairs (>2 weeks from injury): 93% subjective, 94% strength | ||||||||||

| 4 nonoperative: 51% subjective, 71% strength | ||||||||||

| Wolfe et al[16] (1992) | 8 ruptures | 4 repaired: peak torque 105.8% compared with normal side | ||||||||

| 4 nonoperative: peak torque deficit 29.9% compared with normal side |

1.

Aarimaa V, Rantanen J, Heikkila J, et al: Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle.

Am J Sports Med 2004; 32:1256-1262.

2.

Bak K, Cameron EA, Henderson IJP: Rupture of the pectoralis major: a metaanalysis of 122 cases.

Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2000; 8:113-119.

3.

Beloosesky Y, Hendel D, Weis A, et al: Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle in nursing home residents.

Am J Med 2001; 111:233-235.

4.

Carrino JA, Chandnanni VP, Mitchell DB, et al: Pectoralis major muscle and tendon tears: diagnosis and grading using magnetic resonance imaging.

Skeletal Radiol 2000; 29:305-313.

5.

Connell DA, Potter HG, Sherman MF, Wickiewicz TL: Injuries of the pectoralis major muscle: evaluation with MR imaging.

Radiology 1999; 210:785-791.

6.

Egan TM, Hall H: Avulsion of the pectoralis major tendon in a weight lifter: repair using a barbed staple.

Can J Surg 1987; 30:434-435.

7.

Hanna CM, Glenny AB, Stanley SN, Caughey MA: Pectoralis major tears: comparison of surgical and conservative treatment.

Br J Sports Med 2001; 35:202-206.

8.

Kretzler HH, Richardson AB: Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle.

Am J Sports Med 1989; 17:453-458.

9.

Liu J, Wu JJ, Chang CY: Avulsion of the pectoralis major tendon.

Am J Sports Med 1992; 20:366-368.

10.

McEntire JE, Hess WE, Coleman SS: Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle: a report of eleven injuries and review of fifty-six.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1972; 54:1040-1045.

11.

Miller MD, Johnson DL, Fu FH, et al: Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle in a collegiate football player: use of magnetic resonance imaging in early diagnosis.

Am J Sports Med 1993; 21:475-477.

12.

Ohashi K, El-Khoury GY, Albright JP, Tearse DS: MRI of complete rupture of the pectoralis major muscle.

Skeletal Radiol 1996; 25:625-628.

13.

Pavlik A, Csepai D, Berkes I: Surgical treatment of pectoralis major rupture in athletes.

Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 1998; 6:129-133.

14.

Schepsis AA, Grafe MW, Jones HP, Lemos MJ: Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle: outcome after repair of acute and chronic injuries.

Am J Sports Med 2000; 28:9-15.

15.

Simonian PT, Morris ME: Pectoralis tendon avulsion in the skeletally immature.

Am J Orthop 1996; 25:563-564.

16.

Wolfe SW, Wickiewicz TL, Cavanaugh JT: Ruptures of the pectoralis major muscle: an anatomic and clinical analysis.

Am J Sports Med 1992; 20:587-593.