CHAPTER 20 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 20 – Open Rotator Cuff Repair

Multiple facets need to be incorporated to arrive at a successful rotator cuff repair. The process starts with a thorough understanding of the patient’s symptoms, motivation, and ability to comply with postoperative restrictions. Careful examination together with appropriate imaging studies allows proper surgical planning.

Evaluation of the patient with a rotator cuff tear begins with a thorough history. It is critically important to understand the severity of the symptoms and the patient’s ability to comply with postoperative restrictions. The surgeon also needs to elucidate the primary complaint, whether it is pain, weakness, or loss of motion, to better determine and guide the patient’s expectations.

The history ascertains the patient’s dominant extremity as well as occupation. The duration of pain and dysfunction is determined and whether it started with a specific traumatic event. To understand the severity of pain and the degree to which it interferes with the quality of life, patients are asked to rate the pain on a scale of 1 to 10 at rest, with activities, and at night. The patient is also asked about specific alleviating and aggravating factors. Last, patients are asked to localize the pain—whether it occurs over the anterolateral aspect of the shoulder or radiates in a more radicular pattern down the entire arm, possibly consistent with a neurologic component of pain.

If possible, the results of prior studies are obtained, and prior treatment attempts and their results are reviewed. With a history of prior shoulder surgery, operative notes and images can help further delineate the pathologic process.

A focused review of systems is performed to rule out the possibility of other pathologic processes that frequently cause or mimic shoulder pain, such as inflammatory arthritis, cervical radiculopathy, and even thoracic neoplasias. A list of medications and associated medical problems should be recorded.

Physical examination includes inspection and palpation of the entire shoulder, followed by specialized functional tests. Inspection assesses soft tissue swelling, deformity, or atrophy. Palpation comprises an examination of the cervical spine, acromioclavicular joint, and bicipital groove. The neurovascular examination of the extremities includes assessment of strength, sensation, and reflexes.

Subsequently, active and passive shoulder motion is recorded for forward flexion, abduction, internal rotation, and external rotation. Strength is graded on a scale of 1 to 5 for internal rotation, external rotation, flexion, extension, and abduction. Impingement tests have been found to be fairly nonspecific but can help elucidate a diagnosis of subacromial impingement; weakness is suggestive of a tear of the rotator cuff. More specialized tests include the liftoff and belly press tests for subscapularis function, as well as external rotation strength, and the lag sign for infraspinatus function; these allow more sensitive assessment of muscle strength.

Three radiographic views are routinely obtained: 40-degree posterior oblique views with internal and external rotation and an axillary view. One may observe superior subluxation of the humeral head and a decrease in the acromial-humeral distance with significant rotator cuff deficiency. One caveat is that with posterior subluxation, there can be the false appearance of superior humeral head subluxation. There may be sclerosis or rounding of the greater tuberosity with rotator cuff disease as well. The axillary view allows assessment of glenohumeral cartilage loss and subluxation. In addition, one may choose to obtain a Neer outlet view to evaluate acromial morphologic features.

Multiple options are available to further investigate the integrity of the rotator cuff, including arthrography, computed tomographic arthrography, magnetic resonance imaging, and ultrasonography. The decision of which test to perform is based on the individual surgeon’s preference. Magnetic resonance imaging provides important additional information about tear size and configuration, degree of retraction, and muscle atrophy or degeneration.

Indications and Contraindications

After the information obtained from the history, physical examination, and imaging studies is integrated, one determines the diagnosis and can present treatment options to the patient. It is critical to understand the patient’s goals and expectations for surgery. Clearly, the primary indication for rotator cuff surgery is pain relief; recovery of strength and function is less predictable. Contraindications include active or recent infection, significant medical comorbidities, and an inability to follow the postoperative restrictions and rehabilitation.

A detailed conversation with the patient then occurs concerning treatment options. The risk, benefits, and alternatives to surgical repair are discussed in detail. The decision to employ specific techniques, such as open versus arthroscopic repair, is based on the individual surgeon’s preference and familiarity with each technique. I individualize this decision for each patient on the basis of the age of the patient, the physical demands on the shoulder, the size and configuration of the tear, and a primary or revision setting. My practice consists primarily of performing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. However, the technique of open repair may be particularly useful in the revision setting when multiple anchors are already present within the humeral head. In addition, open repair may be considered in the young, active heavy laborer with a large rotator cuff tear.

A combination of regional anesthesia and light sedation or general anesthesia is commonly used for rotator cuff repair, which increasingly is being performed on an outpatient basis. The patient is carefully padded and placed in the beach chair position. The waist should be in approximately 45 degrees of flexion and the knees in 30 degrees of flexion. The table may be slightly rolled away from the surgical shoulder.

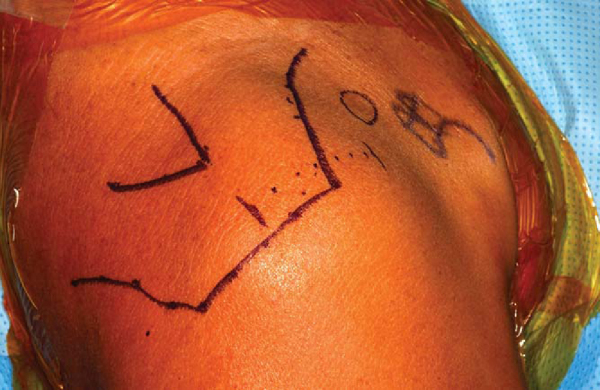

In nearly all patients, regardless of size, one can palpate the posterior scapular spine. The lateral border of the acromion, the anterior border of the acromion, and the anterior portion of the clavicle and coracoid are then marked with a sterile marker (

Fig. 20-1

). If one is performing an arthroscopy before the open repair, one may wish to mark out the standard anterior incision and attempt to place the incision for the anterior portal in line with this future incision.

|

|

|

|

Figure 20-1 |

Specific Steps (

Box 20-1

)

There is significant variability in the skin incision used for open rotator cuff repair, including oblique incisions, horizontal incisions, and vertical incisions. The choice of which incision to use is based on the individual surgeon’s preference.

| Surgical Steps | ||||||||||||

|

An incision is made over the anterior superior aspect of the shoulder parallel with the lateral border of the acro mion in line with Langer’s lines. The length of the skin incision is typically 4 to 5 cm. The skin is incised as well as the fat. The skin flaps are carefully developed and mobilized.

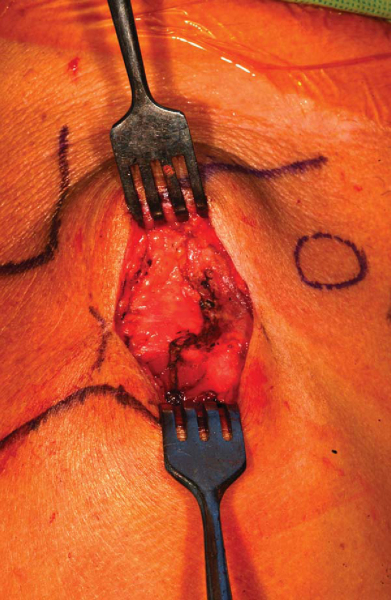

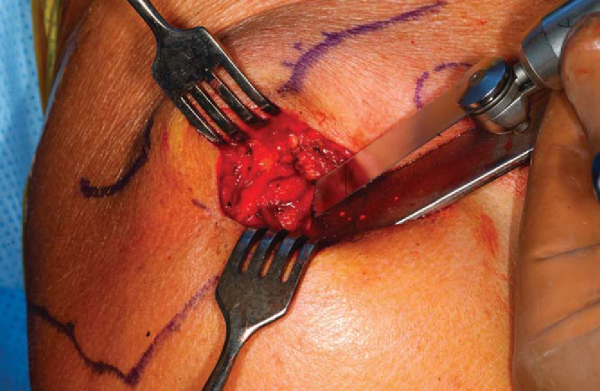

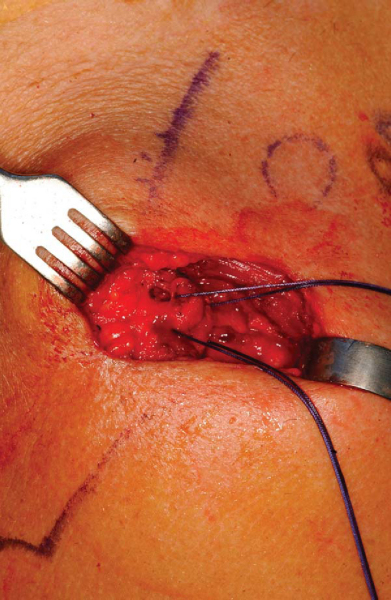

The deltoid muscle insertion into the acromion is clearly identified. There is significant variability among surgeons in regard to the technique with which they take down the deltoid (

Fig. 20-2

). In this example, the deltoid is taken down off the anterior aspect of the acromion with full-thickness sleeves (

Fig. 20-3

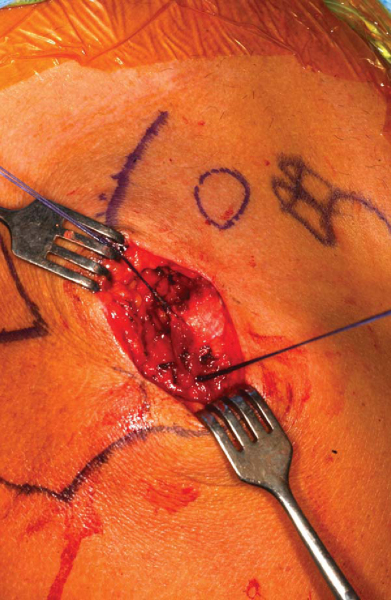

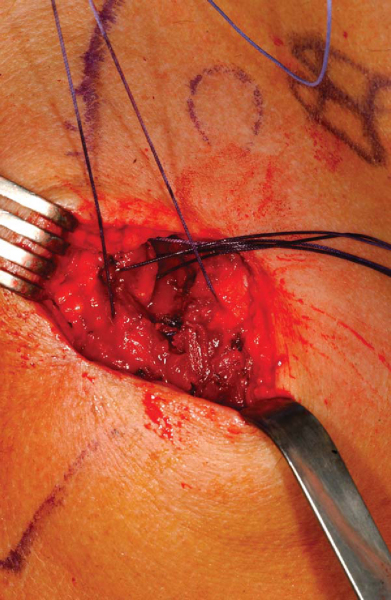

). One must take great care to ensure that this includes both the deep and superficial fascia of the deltoid. The surgeon then has the option either of splitting the deltoid in line with the fibers starting from the acromioclavicular joint anteriorly for approximately 3 cm or of extending the deltoid detachment posteriorly over the lateral border of the acromion. The extent of the deltoid detachment over the lateral acromion border can be modified on the basis of the size of the rotator cuff tear. One must be careful to avoid splitting the deltoid laterally in line with its fibers more than 4 or 5 cm from the acromial border to protect the axillary nerve. However, in most cases, no more than a 2-cm split in line with the fibers of the deltoid is necessary. One can mark the area where the proximal deltoid split is made with a retention stitch (

Fig. 20-4

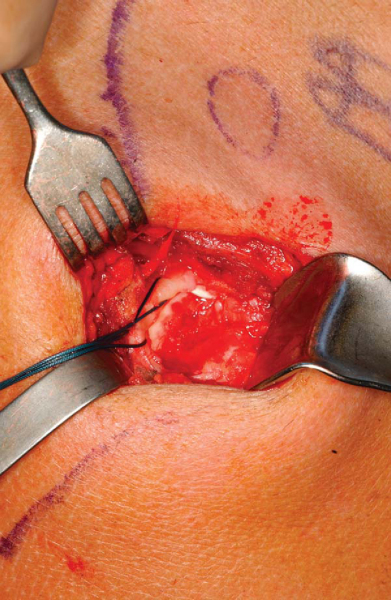

). An additional stitch is usually placed distally in the deltoid split to prevent propagation (

Fig. 20-5

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 20-3 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 20-4 |

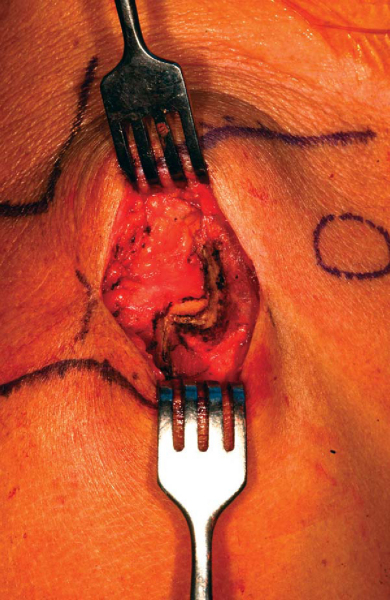

On the basis of the surgeon’s preference, an acromioplasty may then be performed (

Fig. 20-6

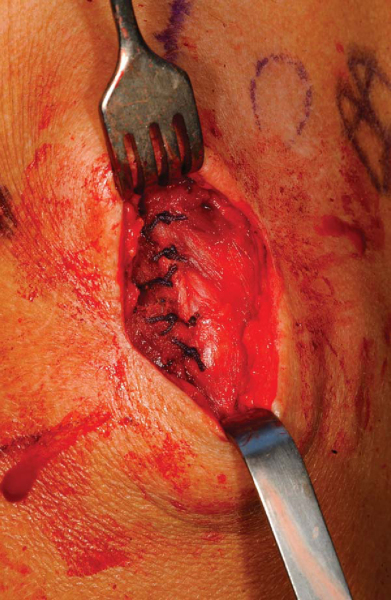

). The torn rotator cuff edges are identified, and retention stitches are placed (

Fig. 20-7

). Systematic releases are then performed to mobilize the tendon. Specifically, one releases overlying bursal adhesions from the torn rotator cuff. Frequently, there is scarring of the coracohumeral ligament to the rotator cuff that must be released. One may also perform intraarticular releases between the labrum and rotator cuff. Care must be taken not to injure the suprascapular nerve in performing medial releases.

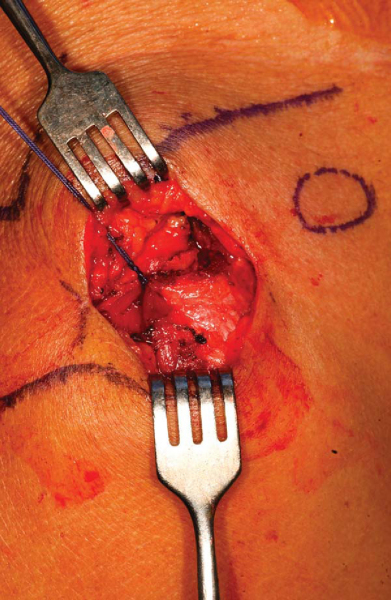

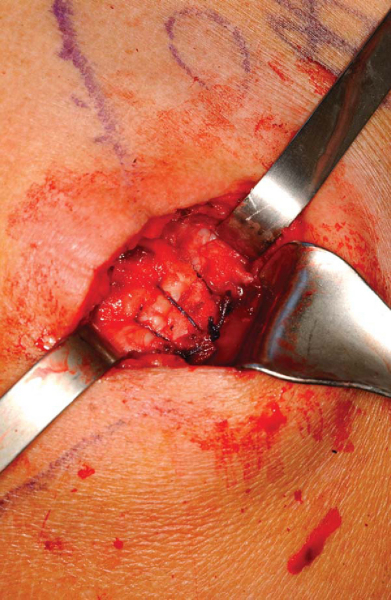

The tendon edges are freshened. The rotator cuff repair can then be performed on the basis of the tear configuration (

Fig. 20-8

). It is my preference in performing a tendon to bone repair to use modified Mason-Allen stitches placed through bone tunnels.

For closure, a meticulous repair of the deltoid is required. At the end of the procedure, the deltoid is repaired back in a tendon to tendon as well as a tendon to bone manner (Figs. 20-9 to 20-11 [9] [10] [11]). Drill holes are placed through the acromion with tendon to bone stitches. In addition, the split within the deltoid itself is repaired with multiple side-to-side stitches. Complications in this approach may be related to deltoid dehiscence postoperatively.

The patient is placed in a shoulder immobilizer. Passive range-of-motion exercises are started with parameters determined at the time of surgery. Pulley and wand exercises are incorporated into the rehabilitation program from week 3 to week 6 on the basis of the individual patient. The patient then progresses to gentle isometric strengthening exercises.

Results of selected series of open rotator cuff repairs are listed in

Table 20-1

.

| Author | No. of Patients | Followup (Mean) | Age of Patient (Mean) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cofield et al[1] (2001) | 105 | 13.4 years | 58 years | 80% satisfactory–excellent results |

| Hawkins et al[3] (1985) | 100 | 4.2 years | 51 years | 94% subjective improvement |

| Ellman et al[2] (1986) | 50 | 3.5 years | 60 years | 84% satisfactory results |

| Neer et al[4] (1988) | 233 | NA | 59 years | 91% satisfactory–excellent results |

A study by Hawkins et al[3] of 100 rotator cuff repairs at a mean followup of 4.2 years revealed that 86% had no or slight pain. All patients had an acromioplasty in addition to the rotator cuff repair. The average abduction improved from 81 to 125 degrees postoperatively. Of 100 patients, 94 considered themselves improved with the surgery. Ellman et al[2] reported the results of open rotator cuff repair in 50 patients with a mean followup of 3.5 years. The results were satisfactory in 84% and unsatisfactory in 16%.

Neer et al[4] reviewed the results of 245 shoulders that underwent rotator cuff repair. Acromioplasty was also performed in 243 of 245 shoulders. Excellent or satisfactory results were obtained in 91% of the shoulders. Cofield et al[1] reviewed the results of 105 shoulders with a chronic rotator cuff tear that underwent open surgical repair and acromioplasty and were observed for an average of 13.4 years. There was satisfactory pain relief in 96 of 105 shoulders. The most frequent complication was apparent failure of rotator cuff healing. Five patients underwent repeated repair. Tear size was found to be the most important determinant of outcome with regard to active motion, strength, rating of the result, satisfaction of the patient, and need for reoperation.

1.

Cofield RH, Parvizi J, Hoffmeyer PJ, et al: Surgical repair of chronic rotator cuff tears: a prospective long-term study.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83:71-77.

2.

Ellman H, Hanker G, Bayer M: Repair of the rotator cuff: end-result study of factors influencing reconstruction.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1986; 68:1136-1144.

3.

Hawkins RJ, Misamore GW, Hobeika PE: Surgery for full thickness rotator cuff tears.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1985; 67:1349-1355.

4.

Neer CS, Flatow EL, Lech O: Tears of the rotator cuff—long term results of anterior acromioplasty and repair.

Orthop Trans 1988; 12:735.