CHAPTER 19 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 19 – Mini-Open Rotator Cuff Repair

Edward V. Craig, MD

The goals of rotator cuff surgery are to reduce pain and to improve shoulder function. To maximize benefit and to minimize surgical morbidity, surgical techniques for rotator cuff repair have shifted from full open techniques, with detachment of the anterior deltoid, to less invasive methods in which more surgery is performed through smaller incisions. Currently, most surgeons approach the rotator cuff through an arthroscopically assisted mini-open technique or a completely arthroscopic procedure. Whichever approach is selected, the fundamental operative aims of satisfactory decompression and secure tendon repair to bone are identical.

Whether the cause of a patient’s shoulder pain is intrinsic tendon degeneration or extrinsic pressure (anatomy of the acromial arch), patients with impingement and rotator cuff irritation generally present with pain during overhead use of the arm. This motion compresses the supraspinatus tendon between the curvatures of the humeral head and acromial arch. This pain is aggravated by use at initial presentation but may progress until patients feel discomfort even at rest. Pain at rest and at night may usually be more indicative of a full-thickness cuff tear. The pain is generally localized to the lateral deltoid and radiates down from the acromion to the deltoid insertion. In addition to pain, patients may experience mechanical symptoms such as popping or clicking as the humeral head rotates against a thickened bursa or coracoacromial ligament.

On objective physical evaluation, clinicians may observe atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus, long head of the biceps rupture, or acromioclavicular joint ganglion. Patients may have decreased active range of motion as a result of cuff weakness. The weakness is especially pronounced with external rotation of the arm near the body and with resisted forward flexion. With larger tears, the rotator cuff no longer stabilizes the humeral head, and the deltoid will pull the humeral head up in the form of a shrug. Whereas passive range of motion is usually preserved in full-thickness tears, long-standing immobilization may lead to secondary stiffness.

Typically, patients with a presentation consistent with impingement or rotator cuff tear are evaluated initially with plain radiographs. A complete series includes anteroposterior, lateral outlet (a lateral view of the scapula taken with a 10-degree caudal tilt of the beam), and axillary views.[2] Cystic changes of the supraspinatus insertion and a subacromial traction spur may be apparent. When large rotator cuff tears exist and the humeral head is no longer depressed by the cuff, the acromiohumeral interval may be narrowed. Radiographic changes in the acromioclavicular joint may be seen, and there is an association between cuff disease and persistent unfused os acromiale.

Both magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography have been useful in diagnosis of cuff tears. Findings may include changes to the acromioclavicular joint, acromion, or humeral head. On magnetic resonance imaging, the key finding of rotator cuff disease is increased signal in both T1- and T2-weighted images. It is possible to identify not only full-thickness lesions but also partial tears, tendon delamination, muscle atrophy or fat infiltration, tendon retraction, and muscle scarring.

The indications for performing rotator cuff repair are generally well established. Dunn et al[4] queried members of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons as to their indications for rotator cuff repair and preferred technique. They found that surgeons who performed a high volume of shoulder surgeries were more likely to recommend cuff repair over conservative treatment and were more positive about the outcomes of surgical intervention versus closed treatment. Of the respondents, 46.2% preferred the mini-open repair versus 14.5% and 36.6% for all-arthroscopic and open repair, respectively. When the decision to fix the rotator cuff has been made, the approach—open, mini-open, or all-arthroscopic—depends on the surgeon’s preference and ability to achieve secure tendon repair.

Whereas all-arthroscopic techniques are increasing as technical methods of fixation improve, there are a number of clinical scenarios in which the open repair may have advantages over the more technically difficult arthroscopic method. These include retracted cuffs, larger tears, and tears involving the subscapularis and biceps dislocation as well as revision cuff surgery. In cases in which a mini-open repair is chosen, an expeditious arthroscopic acromioplasty is usually essential as fluid infiltration can make a mini-open repair difficult.

The advantages of the mini-open technique over a traditional open procedure include anterior deltoid preservation, improved joint visualization, decreased pain, and more rapid return to work or sports. In addition, this approach allows more extensive cuff mobilization and more secure fixation with transosseous sutures compared with the all-arthroscopic technique.[3]

In most instances, anesthesia is achieved by an interscalene block. Additional local anesthesia is used to cover the area overlying the posterior glenohumeral portal that is not anesthetized by the block. After regional anesthesia, the patient is positioned for surgery.

At our institution, shoulder arthroscopy is accomplished with the patient in a beach chair position. The patient is secured by a beanbag device or an operating room table with a head stabilizer. All bone prominences are protected, as is the peroneal nerve distally. This position allows access to the shoulder from a point medial to the scapula. The arm is prepared and draped free in the normal sterile fashion.

The mini-open rotator cuff repair is a hybrid of arthroscopic evaluation and débridement of the glenohumeral joint, subacromial space, bursa, and rotator cuff followed by a small open approach to relocation of the cuff tendon back down to bone.

Surgical Landmarks and Incisions

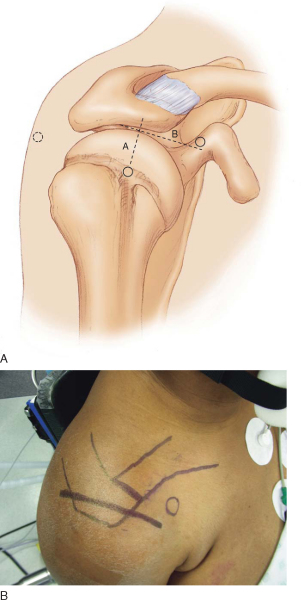

Mini-open rotator cuff repair is initiated after an expeditious subacromial decompression (described elsewhere). Although the lateral portal may be simply extended, an anterior superior skin incision following Langer’s lines is more aesthetic and avoids the “dimpling” frequently seen with a lateral portal extension. This incision may extend from lateral to the coracoid process past the anterolateral corner of the acromion. The length of the incision is approximately 3 to 4 cm (

Fig. 19-1

). Before incision, the skin is infiltrated with a 1 : 500,000 concentration of epinephrine to minimize bleeding.

|

|

|

|

Figure 19-1 (A redrawn from Craig E. Mini-open and open techniques for full-thickness rotator cuff repairs. In Craig E, ed. The Shoulder. Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004:309-340.) |

Specific Steps (

Box 19-1

)

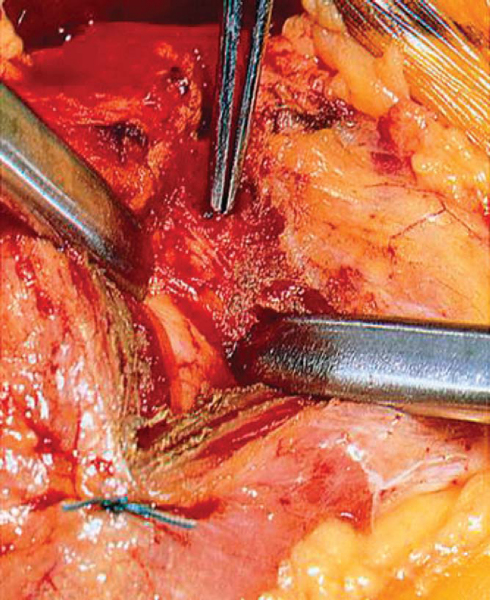

The soft tissue is dissected off the deltoid fascia to develop small full-thickness flaps. The previous portal site is easily visualized, and the deltoid is split in line with its fibers to the level of the anterior acromion (

Fig. 19-2

). The distal extent of the deltoid split is limited by placement of a stay suture (No. 1 Tevdek) to avoid damage to the axillary nerve.

|

|

|

|

Figure 19-2 (From Craig E. Mini-open and open techniques for full-thickness rotator cuff repairs. In Craig E, ed. The Shoulder. Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004:309-340.) |

Self-retaining retractors are placed deep under the anterior and posterior edges of the deltoid split to reveal the underlying bursal tissue. Subdeltoid scarring may prevent retractor insertion, requiring blunt dissection before retractor placement. Although much of the subacromial bursa will have previously been excised arthroscopically, any remaining bursa is dissected off the rotator cuff tendon sharply for optimal visualization. At this point, it is easy to palpate the acromion and to evaluate the adequacy of the acromioplasty. The acromion can be modified at this point if necessary.

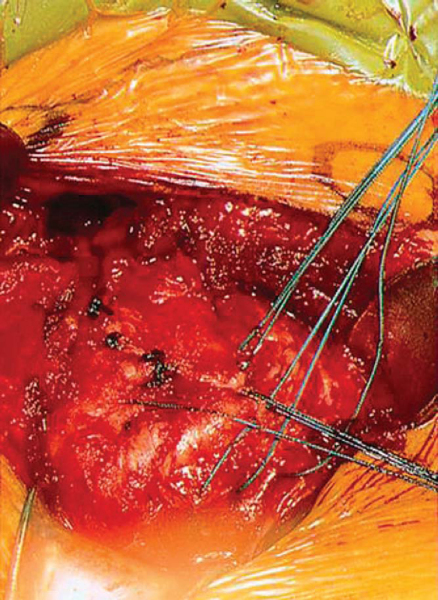

The cuff tear may be readily apparent in the wound at this point. If it is not or the tendon is retracted, rotation of the arm will bring it into view. The supraspinatus insertion, the most frequent site of tendon disease, is readily seen by this method. At this point, it is possible to precisely identify the rotator cuff anatomy, the shape of the tendon tear, and the involved tendons and their positions relative to the glenoid. The supraspinatus tendon is sometimes retracted by the pull of the coracohumeral ligament and superior capsule. If necessary, the tendon can be mobilized by the release of the extra-articular and intraarticular adhesions or by the release of the coracohumeral ligament and rotator interval.

A nonabsorbable stay suture, such as No. 2 Ethibond, is passed through the tendon edge to facilitate traction during this process. This avoids crushing of the tendon with clamps (

Fig. 19-3

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 19-3 (Redrawn from Craig E. Mini-open and open techniques for full-thickness rotator cuff repairs. In Craig E, ed. The Shoulder. Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004:309-340.) |

Once the tendon is mobilized, the frayed edge of the tendon may be freshened. Care should be taken to avoid excessive tendon removal. A shaver or rasp is used to remove any remaining soft tissue from the rotator cuff footprint. Establishment of a bleeding bed may not be essential, however, as Fealy et al[5] reported that the lowest cuff vascularity is at the anchor site or cancellous trough. The key blood supply for healing appears to be in the peritendinous region.

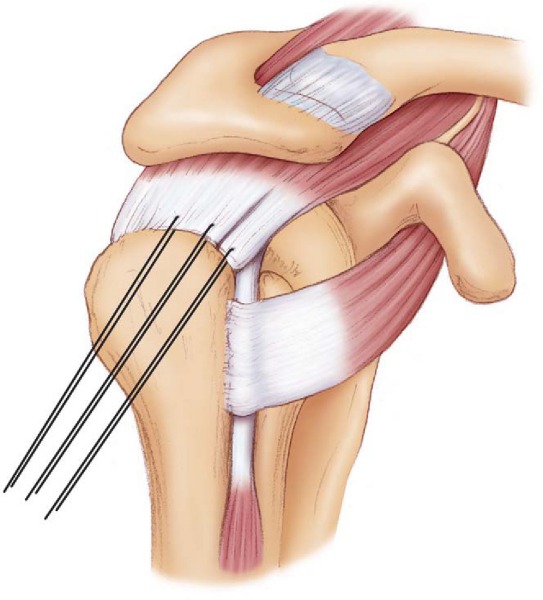

The rotator cuff tendons are then reattached to their original bone insertions by drill holes through bone, by use of suture anchors, or by a combination of both. Suture anchors are placed at appropriate intervals in the tuberosity, and the tendon is tied securely to the original footprint. When bone tunnels are used, holes are drilled with a 1/8-inch drill bit through the lateral side of the greater tuberosity. Matching holes are made in the footprint with the tunnels communicating. Sutures are passed through the tunnels and in a Mason-Allen or figure-of-eight pattern through the tendon edge (

Fig. 19-4

). Sutures are placed approximately 1 cm apart. A typical supraspinatus tear requires three interrupted sutures.

|

|

|

|

Figure 19-4 (Redrawn from Craig E. Mini-open and open techniques for full-thickness rotator cuff repairs. In Craig E, ed. The Shoulder. Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004:309-340.) |

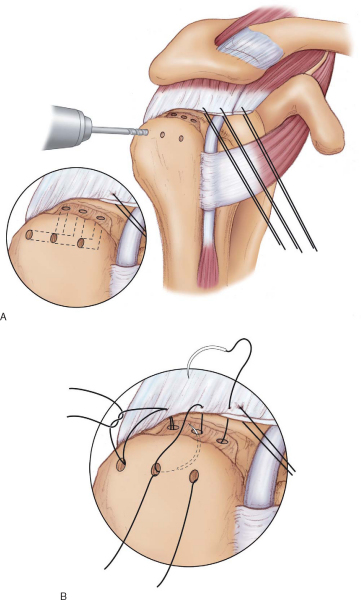

A combination of suture anchors and bone tunnels may be used in a double-row configuration to secure a larger surface area of tendon back down to bone. In this case, the suture anchors are placed more medially at the anatomic neck, with the bone tunnels providing lateral fixation of the tendon edge (

Fig. 19-5

). When possible, the arm should be kept at the patient’s side during knot tying. Repair of the tendon with the arm abducted will place tension on the fixation when the arm returns to the side and increase the likelihood of failure.

|

|

|

|

Figure 19-5 (From Craig E. Mini-open and open techniques for full-thickness rotator cuff repairs. In Craig E, ed. The Shoulder. Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004:309-340.) |

At this point, the arm is brought into forward elevation and external rotation, and the adequacy of the repair is evaluated. This also provides assurance of safe range of motion in the initial postoperative period.

The wound is then copiously irrigated. Retractors are removed from the deltoid edges, as is the stay stitch, and the deltoid edges are approximated. The skin is closed in two layers, a sterile dressing is placed, and a sling is used to protect the repair.

Early passive range of motion is initiated postoperatively with protection of the cuff repair on day 1. Supine passive forward flexion and supine external rotation begin on day 1 with the assistance of a therapist. The patient is taught to perform circular Codman exercises while bending over to 90 degrees at the waist. All exercises in the immediate postoperative period must be done passively. At 6 weeks postoperatively, active exercises and light activity are permitted. Resistive exercises for the deltoid and rotator cuff are allowed after 3 months.

Several complications can accompany the mini-open rotator cuff repair.[3] Terminal branches of the axillary nerve may be injured if the deltoid split extends more than 4 to 5 cm distal to its origin. This danger can be minimized by placement of a stay suture at the distal extent of the split to prohibit progression.

Care must be taken to firmly secure the rotator cuff tendon down to bone. Insecure repair of rotator cuff tendon may lead to repeated rupture or tissue gapping, inadequate healing, continued pain, and weakness. Finally, an excessively long arthroscopic portion of the procedure will lead to the distention of the soft tissues and skin, subcutaneous tissue, and deltoid. This obscures the bone landmarks and makes subdeltoid dissection difficult.

| PEARLS AND PITFALLS | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Most investigators report success of more than 80% for mini-open rotator cuff repair in terms of pain control and return of function (

Table 19-1

). In 2005, Baysal et al[1] documented functional outcomes and quality of life in 84 patients undergoing a mini-open cuff repair. Of their group, 96% of the patients were satisfied or very satisfied with surgical outcome, and 78% returned to unmodified work by 1 year postoperatively. Interestingly, neither the patient’s age nor the size of the cuff tear affected outcomes, and most improvement was seen by the 6-month postoperative visit with continued improvement until 1 year. Shinners et al[10] described 67 patients undergoing mini-open cuff repair; 93% received good or excellent outcomes ratings, with all patients experiencing decreased pain and improved function postoperatively. Again, tear size and age of the patient did not affect outcome. A double-row mini-open technique was found effective for the treatment of cuff tears of all sizes by the Hospital for Special Surgery group.[6] Seventy-five consecutive patients underwent arthroscopically assisted mini-open cuff repair and were observed for a minimum of 24 months. There was no detectable difference in outcomes between patients with small, moderate, or large cuff tears.

| Author | Followup | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Baysal et al[1] (2005) | >1 year | AACR: 96% satisfied or very satisfied; 78% returned to unmodified work by 1 year |

| Sauerbrey et al[9] (2005) | 3 years | No difference between AACR and MOR |

| Warner et al[11] (2005) | 27 months | No difference between AACR and MOR |

| Kim et al[7] (2003) | Mean: 39 months | No difference between AACR and MOR |

| Fealy et al[6] (2002) | Minimum of 2 years | AACR: 75 patients; no detectable difference by tear size |

| Shinners et al[10] (2002) | 3 years | AACR: 93% good or excellent |

More studies have compared rotator cuff repair by the mini-open approach and an all-arthroscopic approach. Warner[11] retrospectively summarized his initial experience with mini-open cuff repair versus all-arthroscopic cuff repair. He found no difference in outcomes between the two groups in terms of clinical outcomes, satisfaction of patients, or recovery time and suggested that the approach is based on the preference of the surgeon or patient. Another retrospective comparison looked at 54 patients undergoing cuff repair with an average of 36 months of followup. By use of the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score, improvements in pain, satisfaction, and functional outcomes were not significantly different between mini-open cuff repair and all-arthroscopic cuff repair groups.[9] Kim et al[7] reported their retrospective case series of 76 patients treated for full-thickness cuff tears by all-arthroscopic techniques or mini-open salvage of unsuccessful arthroscopic repairs. The mean followup was 39 months. All patients in both groups had improved ASES scores, with no significant difference in scores, pain, or return to activity between the groups. This study found outcomes to be dependent on tear size and not treatment technique.

The current literature examining the outcomes of rotator cuff surgery is composed of level III and IV studies, and these do not conclusively answer the question of whether all-arthroscopic or mini-open repairs provide better outcomes for patients with small or moderate-sized rotator cuff tears. A large national multicenter study is being undertaken in Canada to answer this question in a prospective manner.[8]

1.

Baysal D, Balyk R, Otto D, et al: Functional outcome and health-related quality of life after surgical repair of full-thickness rotator cuff tear using a mini-open technique.

Am J Sports Med 2005; 33:1346-1355.

2.

Craig E: Impingement and rotator cuff tear: treatment by anterior acromioplasty and repair.

In: Craig E, ed. Clinical Orthopaedics,

Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:213-221.

3.

Craig E: Mini-open and open techniques for full-thickness rotator cuff repairs.

In: Craig E, ed. The Shoulder. Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery,

Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:309-340.

4.

Dunn W, Schackman B, Walsh C, et al: Variation in orthopedic surgeons’ perceptions about the indications for rotator cuff surgery.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87:1978-1984.

5.

Fealy S, Adler R, Drakos M, et al: Patterns of vascular and anatomical response after rotator cuff repair.

Am J Sports Med 2006; 34:120-127.

6.

Fealy S, Kingham TP, Altchek DW: Mini-open rotator cuff repair using a two-row fixation technique: outcomes analysis in patients with small, moderate, and large rotator cuff tears.

Arthroscopy 2002; 18:665-670.

7.

Kim SH, Ha KI, Park JH, et al: Arthroscopic versus mini-open salvage repair of the rotator cuff tear: outcome analysis at 2 to 6 years’ followup.

Arthroscopy 2003; 19:746-754.

8.

MacDermid J, Holtby R, Razmjou H: All-arthroscopic versus mini-open repair for small or moderate-sized rotator cuff tears: a protocol for a randomized trial [NCT00128076].

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2006; 7:25.

9.

Sauerbrey A, Getz C, Piancastelli M, et al: Arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: a comparison of clinical outcome.

Arthroscopy 2005; 21:1415-1420.

10.

Shinners T, Noordsij P, Orwin J: Arthroscopically assisted mini-open rotator cuff repair.

Arthroscopy 2002; 18:21-26.

11.

Warner J, Tetreault P, Lehtinen J, Zurakowski D: Arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: a cohort comparison study.

Arthroscopy 2005; 21:328-332.

12.

Youm T, Murray D, Kubiak E, et al: Arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: a comparison of clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005; 14:455-459.