Brachial Plexus Blocks

II – Single-Injection Peripheral Blocks > A – Upper Extremity > 7

– Brachial Plexus Blocks

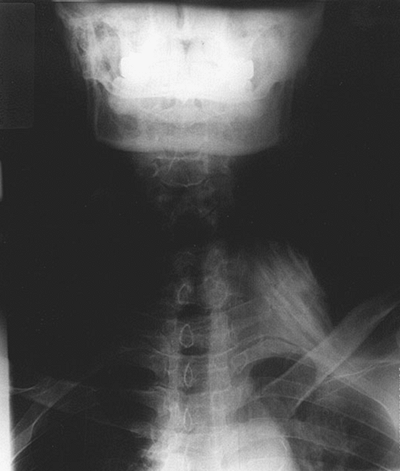

The cricoid cartilage (indicative of the transverse process of C6), the

clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and the anterior and

middle scalene muscles with the interscalene groove in between (Fig. 7-1).

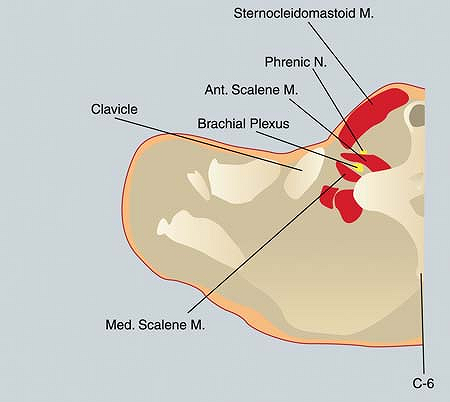

The cricoid cartilage is identified with the head in the neutral

position. The patient is then instructed to turn his or her head 30° to

the opposite side and to raise the head slightly off the bed. The two

heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle are identified with particular

emphasis being placed on the lateral border of the clavicular head (Fig. 7-2A).

Next, the patient is asked to place the head back on the bed and relax.

The anterior scalene muscle is then identified immediately lateral and

deep to the lateral border of the clavicular head, and the fingers are

rolled or “walked” laterally into the interscalene groove between the

anterior and middle scalene muscles. The interscalene groove is marked.

A horizontal line is drawn at the level of the cricoid cartilage

laterally to intersect the interscalene groove. The insulated needle

connected to a nerve stimulator (1.0 mA, 2 Hz, 0.1 ms) is inserted at

the point of intersection between these two lines and is directed

perpendicularly to the skin in a medial, caudal, and posterior

direction (Fig. 7-2B).

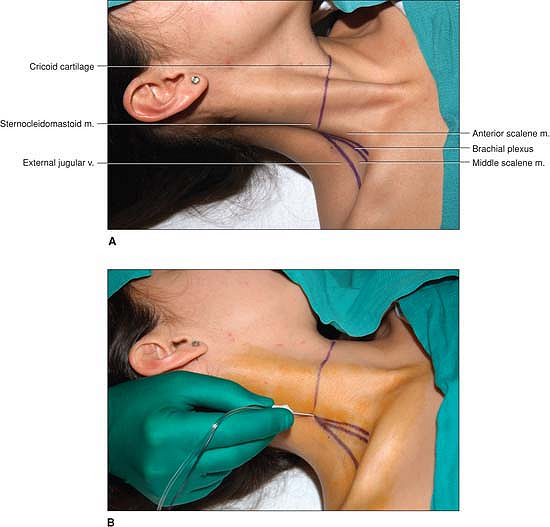

The position of the needle is adjusted to maintain the same motor

response with a current less than 0.5 mA. After negative aspiration for

blood, the local anesthetic is slowly

injected with repeated aspiration for blood every 5 mL to be distributed around the brachial plexus (Fig. 7-3).

|

|

Figure 7-1.

The cricoid cartilage, the clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and the anterior and middle scalene muscles with the interscalene groove in between. |

Inability to elevate the arm (the “deltoid sign”). (b) The “money

sign,” in which the patient rubs the thumb against the index and middle

fingers indicating the onset of paresthesia or numbness in the

distribution of C6 and C7.

-

Sedation should be minimal, its purpose to allay anxiety without inhibiting the ability of the patient to communicate.

-

In a limited number of patients, the

clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is either not present

or exists as an indistinct band. In these situations, the interscalene

groove is situated 3 cm lateral to the lateral border of the main belly

of the sternocleidomastoid muscle at the level of the cricoid

cartilage. This “3-cm mark” is a useful aid in obese individuals as

well. Additional landmarks include the external jugular vein and the

pulsation of the subclavian artery as it crosses over the first rib

between the anterior and middle scalene muscles at the lower end of the

interscalene groove. -

Patient discomfort is reduced by superficially infiltrating the skin with lidocaine using a 26-gauge needle.

-

To facilitate the insertion of the insulated needle, the skin can first be punctured with an 18-gauge needle.P.60

Figure 7-2. A:

Figure 7-2. A:

The two heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle are identified with

particular emphasis being placed on the lateral border of the

clavicular head. B: The insulated needle

connected to a nerve stimulator is inserted at the point of

intersection between these two lines and directed perpendicularly to

the skin in a medial, caudal, and posterior direction. -

Insertion of the insulated needle with

the bevel facing the sheath increases the likelihood of feeling the

tactile sensation of “popping through the sheath.” -

Diaphragmatic movement is indicative of

stimulation of the phrenic nerve and of needle placement

medial/anterior to the interscalene groove. The needle should be

withdrawn and redirected in a more lateral/posterior direction. In

contrast, a suprascapular or trapezius muscle contraction is indicative

of needle placement lateral to the interscalene groove. The needle

should be withdrawn and redirected in a more medial/anterior direction. -

Positioning of the needle to maintain a motor response at 0.3 to 0.5 mA is associated with a high success rate.

-

It is essential that the caudal direction of the needle be maintained (Fig. 7-4). Insertion of the needle in a neutral/horizontal direction (i.e., midway between caudal

P.61

and cephalad) or in a cephalad direction facilitates neuraxial

positioning of the needle as well as the vertebral artery injection of

local anesthetic.![]() Figure 7-3.

Figure 7-3.

The local anesthetic is slowly injected with repeated aspiration for

blood every 5 mL to be distributed around the brachial plexus. -

A triangular-shaped swelling of the apex

at the point of needle insertion and the base at the lower end of the

interscalene groove may be noted, especially in thin individuals, as

the injection progresses and is indicative of correct needle placement.

In contrast, a circular swelling around the point of needle insertion

is more likely indicative of injection into the subcutaneous tissues

(i.e., superficial to the brachial plexus sheath). -

“Pressure paresthesia,” which is

described as a dull ache following the rapid injection of 2 to 3 mL of

local anesthetic, should be differentiated from the severe pain

produced by an intraneural injection. This “pressure paresthesia”

appears to be more commonly encountered with an interscalene block than

with other peripheral nerve blocks and may be referred to the shoulder

or more distally. -

This block is not indicated alone for a

surgery involving an area around the axilla (e.g., inferior capsular

shift). In addition, variations in the extent of T2 innervation may

result in inadequate anesthesia of the anterior and posterior

arthroscopic portal sites. These limitations can be overcome by local

infiltration to the appropriate sites. -

An interscalene block is not indicated

alone for surgery to the medial aspect of the upper extremity, as nerve

roots C8 and T1 are not consistently blocked with this approach to the

brachial plexus.P.62 Figure 7-4. The caudal direction of the needle needs to be maintained.

Figure 7-4. The caudal direction of the needle needs to be maintained. -

Side effects are commonly associated with

an interscalene block. A 100% incidence of phrenic nerve blockade (due

to the phrenic nerve’s C3-5 derivation) occurs, resulting in paresis of

the ipsilateral diaphragm. This results in a 25% to 30% reduction in

pulmonary function volumes. Caution is therefore advised in patients

with significantly reduced lung function. The patient should be

reassured that hoarseness (vasodilation of the larynx and arytenoids or

blockade of the recurrent laryngeal nerve) and Horner syndrome

(cervical sympathetic nerve block) are benign and transient. -

Serious complications associated with the

performance of this block include epidural, subdural, and spinal

injections and even injections directly into the spinal cord; arterial

(vertebral artery) and venous intravascular injections; as well as

pneumothorax.

JL. Permanent loss of cervical spinal cord function associated with

interscalene block performed under general anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2000;93:1541–1544.

A, Ekatodramis G, Kalberer F, et al. Acute and nonacute complications

associated with interscalene block and shoulder surgery. Anesthesiology 2001;95:875–880.

AR. The use of a “reverse” axis (axillary-interscalene) block in a

patient presenting with fractures of the left shoulder and elbow. Anesth Analg 2001;93:1618–1620.

A, Fanelli G, Aldegheri G, et al. Interscalene brachial plexus

anaesthesia with 0.5%, 0.75% or 1% ropivacaine: a double-blind

comparison with 2% mepivacaine. Br J Anaesth 1999;83: 872–875.

S, Greengrass R, Steele S, et al. A comparison of 0.5% bupivacaine,

0.5% ropivacaine, and 0.75% ropivacaine for interscalene brachial

plexus block. Anesth Analg 1998;87:1316–1319.

W, Saiyed M, Brown A. Interscalene block with a nerve stimulator: a

deltoid motor response is a satisfactory endpoint for successful block.

Reg Anesth Pain Manag 2000;25:356–359.

W, McDonald M. Hemidiaphragmatic paresis during interscalene brachial

plexus block: effects on pulmonary function and chest wall mechanics. Anesth Analg 1992;74:352–357.

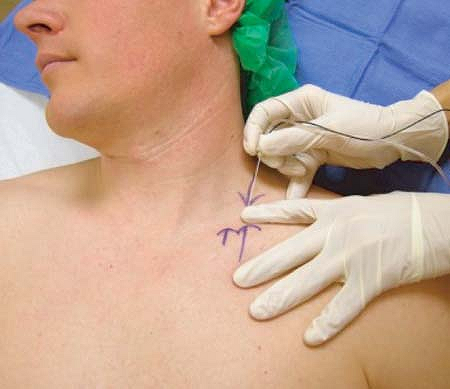

The patient is placed in a semi-sitting position, about 35° to 45° from

the horizontal plane, with the head turned to the opposite side. The

arm on the operative side is adducted, the shoulder is down and the

elbow is flexed, as shown in Figure 7-5.

Anesthesia and postoperative analgesia for any surgical procedure on

the upper extremity that does not involve the shoulder. It is an ideal

technique for surgery on the elbow, the forearm, the wrist, as well as

the hand.

|

|

Figure 7-5. Patient positioning with shoulder down and elbow flexed.

|

|

|

Figure 7-6.

Needle insertion: Two new arrows are drawn lateral to the original one. The upper arrow pointing down shows the needle insertion point. The lower arrow pointing up together with the upper arrow show the direction of needle insertion, which is caudad and parallel to the patient’s midline. |

The lateral (posterior) border of the sternocleidomastoid is identified

and traced caudally to the point where it meets the clavicle. This

point is marked with an arrow on the skin covering the clavicle. This

mark is used as a reference to find the needle insertion point, which

in adults, lies at a distance of approximately 1 in (2.5 cm) lateral to

it and one fingerbreadth above the clavicle.

cephalad and parallel to the clavicle at this level where the operator

usually is able to palpate the elements of the brachial plexus. The

needle insertion point is located immediately cephalad to the palpating

finger or one fingerbreadth above the clavicle as indicated by the

lateral upper arrow in Figure 7-6.

A small skin wheal of local anesthetic is raised at this level and the

insulated needle connected to a nerve stimulator (0.8–0.9 mA, 1 Hz, 0.1

ms) is inserted first perpendicular to the skin (easier penetration)

and then under the palpating finger in a caudal direction that is also

parallel to the patient’s midline as shown in Figure 7-6.

(upper trunk). The needle is then slowly advanced until a twitch of the

fingers, either in flexion or extension is visible. The local

anesthetic solution is slowly injected with frequent aspirations.

-

As it is the case with any regional

anesthesia technique, positioning of the patient is very important. No

attempts should be made at identifying any structures before

P.65

achieving

satisfactory posture. While the block can be performed with the patient

supine it is more comfortable for the patient—and no more complicated

for the operator—to have the patient sit up. Bringing the patient’s

shoulder down “opens” the supraclavicular area and facilitates the

technique. -

The point at which the lateral head of

the sternocleidomastoid meets the clavicle is where the “plumb bob”

technique is attempted. This point is located too close to the dome of

the pleura so we use it only as a reference point from which we locate

the needle insertion point in adults at about 1 in (2.5 cm) lateral to

it. We call this distance “margin of safety.” -

In patients with well-developed

sternocleidomastoid muscles, the width of its clavicular head can be

used to determine this margin of safety. -

We do not routinely rely on the palpation of either the subclavian artery pulse or the scalene muscles.

-

To easier penetrate the skin the needle

is first inserted perpendicular to it before changing its direction to

advance it caudally, parallel to the patient’s midline. -

A motor response from one of the trunks

of the plexus should be obtained in every patient at a depth of 2 cm or

less. If no motor response is obtained, the nerve stimulator status and

the indemnity of the electric circuit are checked before proceeding to

reassess the landmarks if necessary. -

With the supraclavicular block the type

of response elicited (i.e., fingers twitch) is more important than the

output at which such response is obtained provided that the output is

no greater than 0.9 mA, as we demonstrated in a prospective study. -

Flexion and extension of the wrist are

acceptable motor responses but supination or pronation of the wrist and

other more proximal responses are not. -

While the block may be followed by 50%

phrenic nerve paralysis it did not trigger symptoms in healthy

volunteers according to a study by Neal and collaborators. Our

experience confirms this. -

A block of the intercostobrachial

branches, also called “tourniquet block” or T2 block, is usually

unnecessary unless the surgical incision falls in the upper medial side

of the arm. Tourniquet pain usually is unavoidable after 2-h tourniquet

time whether this supplemental block is performed or not. This time

also marks the maximum allowable time for a tourniquet to remain

inflated.

CD, Domashevich V, Voronov G, Rafizad A, Jelev T. The supraclavicular

block with a nerve stimulator: to decrease or not to decrease, that is

the question. Anesth Analg 2004;98:1167–1171.

CD, Gloss FJ, Voronov G, Tyler SG, Stojiljkovic LS. Supraclavicular

block in the obese population: an analysis of 2020 blocks. Anesth Analg 2006;102:1252–1254.

JM, Moore JM, Kopacz DJ, Liu SS, Krammer DJ, Plorde JJ. Quantitative

Analysis of Respiratory, Motor, and Sensory Function After

Supraclavicular Block. Anesth Analg 1998;86:1239–44

Supine, with the hand of the side to be blocked positioned in a relaxed

manner on the abdomen, and the head slightly turned to the

contralateral side.

Anesthesia and immediate postoperative analgesia of any surgical

procedure in the region of the distal upper arm, the forearm, and the

hand.

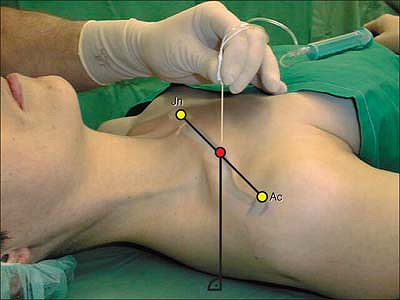

The brachial plexus crosses beneath the clavicle in the vicinity of the

middle of the clavicular line drawn between the halfway point of the

ventral apophysis of the acromion and the jugular notch. In dissected

cadavers, the plexus lay at a maximum depth of 4 cm lateral to the

axillary artery and vein, where its three cords always converge at the

entrance to the trigonum of the clavipectoral fascia.

The ventral apophysis of the acromion and the jugular notch is

identified and the line joining these two points is drawn. The middle

of this line determines the site of introduction of the needle. The

insulated needle connected to a nerve stimulator (1.5 mA, 2 Hz, 0.1 ms)

is introduced directly beneath the clavicle and in a strictly vertical

direction (Fig. 7-7).

Usually, the lateral cord (contractions of the biceps muscle) is

stimulated. The position of the needle is adjusted to maintain the same

motor response with a current less than 0.3 mA. After negative

aspiration for blood, the appropriate volume of local anesthetic is

slowly injected, with repeat aspiration for blood every 5 mL to be

distributed around the brachial plexus (Fig. 7-8).

-

A complete blockade will develop within 5 to 15 minutes.

-

The most likely motor response predictive

of a complete block is the contraction of the finger muscles: extensors

or flexors (stimulation of either the radial or median nerve). -

Precise determination of the specific

anatomical landmarks is essential for the success and safety of this

block. Following the described landmarks, no injury of nerves, vessels,

or even the pleura have been induced in cadaver studies. -

In contrast to the jugular notch, the

exact determination of the ventral apophysis of the acromion lateral

point is occasionally more difficult. This point, however, is essential

for accurate determination of the puncture site. For that purpose, the

clavicle

P.67

may

be palpated from medial to lateral leads to the acromioclavicular

joint. This means the ventral apophysis of the acromion must be sought

ventrally and slightly laterally. Another approach is based on

following the crest of the scapula up to the acromion with the

assumption that the ventral apophysis is posterior. To rule out the

head of the humerus, the arm is passively moved and at the same time

the assumed landmark is identified. The latter should not move in

conjunction with this manipulation. The coracoid is considerably more

medial and may be clearly felt in most patients. Figure 7-7.

Figure 7-7.

The insulated needle connected to a nerve stimulator is introduced

directly beneath the clavicle and in a strictly vertical direction. -

The measurement must be started from exactly in the middle of the jugular notch.

-

The distance between the puncture site

and the clavicle must be kept at a minimum (however, painful contact

with the periosteum should be avoided). -

If blood is aspirated, it means that the

puncture site is too medial. In contrast, if no motor responses are

elicited, the appropriateness of the puncture site should be confirmed.

If the second attempt is unsuccessful, the puncture site should be

shifted 0.5 to 1.0 cm laterally. If this correction of the puncture

site still does not produce the desired stimulation response, adjust

the position 0.5 to 1.0 cm in a medial direction from the original site. -

If primarily biceps muscle motor response

is elicited, the position of the needle needs to be slightly more

lateral and deeper (the perpendicular/vertical direction to meet the

posterior cord). Finally, in the exceptional case that the puncture

site cannot be defined with certainty, then another procedure should be

used. Under no circumstances should one simply “poke about” or ever

change from a vertical puncture direction. -

The appropriate positioning of the patient allows optimal observation of the peripheral muscle contractions.

-

Cardinal mistakes: (a) Puncture site too

lateral: false localization of the lateral landmark associated with a

high risk for axillary artery or vein injury. (b) Puncture depth

P.68

greater

than 6 cm: In cadavers, injury to the pleura can occur (pneumothorax);

however, the first rib provides relatively good protection, especially

in the event of faulty medial punctures. (c) Puncture site too medial

(subclavian artery, subclavian vein, or cephalic vein puncture).![]() Figure 7-8.

Figure 7-8.

After negative aspiration for blood, the appropriate volume of local

anesthetic is slowly injected, with repeat aspiration for blood every 5

mL to be distributed around the brachial plexus.

M, Kaiser H, Uhl M. Biometric data on risk of pneumothorax from

vertical infraclavicular brachial plexus block. A magnetic resonance

imaging study. Anästhesist 2001;50:511–516.

Supine, arm resting at patient’s side with the palm up (to make

hand/wrist motion with nerve stimulation easier to identify). Patient

may use a pillow behind the head, but the entire shoulder and back

should lie flat against the gurney. The operator stands on the side

ipsilateral to the extremity to be blocked, facing cephalad.

Surgery of the upper extremity at, or distal to, the elbow. The

intercostobrachial (ICB) nerve, which often helps to innervate the skin

over the medial epicondyle, is often spared surgical anesthesia with

this block.

The brachial plexus is intersected between 2 and 8 cm deep to the skin

(average: 4 cm). Therefore, for small and average-sized patients, a

5-cm, 22-gauge insulated stimulating needle is preferred. However, with

larger patients, a longer needle is often necessary.

40 to 50 mL for adults. The medial or lateral cord is most often

initially identified using the coracoid technique, and a relatively

large volume of local anesthetic is usually necessary to reach the

posterior cord, located posterior to the axillary artery.

The coracoid process of the scapula is the sole anatomic landmark. To

find the coracoid process, place two fingers in the groove between the

deltoid and pectoralis major muscles, and gently palpate laterally.

From the center of the coracoid process, mark a point that is exactly 2

cm medial and 2 cm cauda1 (Fig. 7-9). This is the needle entry point.

Raise a skin wheal at the needle entry point. The needle is then

inserted through the skin wheal with long axis of the needle

perpendicular to the gurney in all planes (Fig. 7-9).

With continuous aspiration and the nerve stimulator initially set at

1.2 mA and 2 Hz, the needle is advanced directly posterior. If the

brachial plexus is not identified after 5 to 8 cm of insertion,

depending on patient habitus, the needle is withdrawn to the skin and

redirected either cephalad or caudal in the paramedian sagittal plane

until discrete, stimulated motion occurs in any digit(s) with a current

<0.50 mA. Directing the needle tip out of the paramedian sagittal

plane must be avoided—neither medially

toward the lung, nor laterally, toward the individual terminal nerves

of the brachial plexus. Flexion or extension at the elbow or wrist that

results in motion of the fingers, without intrinsic hand/digit motion,

should be rejected.

-

Directing the needle tip out of the

paramedian sagittal plane medially toward the chest wall increases the

risk of a pneumothorax. -

Directing the needle tip out of the

paramedian sagittal plane laterally may place the needle tip lateral to

the cords and result in anesthesia of only one or two terminal nerves

of the arm. -

Frequently, the first motion elicited

results from direct stimulation of the pectoral major and minor

muscles. The needle must be advanced further since the brachial plexus

lies posterior to these muscles. -

Any limb motion other than intrinsic

finger flexion or extension must be rejected as these endpoints result

in a 60% failure rate.P.70 Figure 7-9. From the center of coracoid process, mark a point that is exactly 2 cm medial and 2 cm caudal. This is the needle entry point.

Figure 7-9. From the center of coracoid process, mark a point that is exactly 2 cm medial and 2 cm caudal. This is the needle entry point. -

If biceps or forearm motion occurs,

redirect the needle caudal in the paramedian sagittal plane. Changes to

the needle trajectory should be made in small increments. -

The ICB nerve courses adjacent to the

brachial plexus at the level of the cords. The infraclavicular block

will usually produce analgesia in this nerve to cover the majority of

tourniquet pain. However, while surgical anesthesia of the ICB

frequently occurs, this block should not be relied on to consistently

produce surgical anesthesia of the medial aspect of the arm above the

elbow. -

A “vertical” technique using a needle

entry point just caudal to the clavicle and medial to the entry point

of the coracoid technique has resulted in a number of reported

pneumothoraxes. The investigator who first described the coracoid

technique reported that even with deliberate attempts to penetrate the

thoracic cavity in cadavers, it proved impossible to enter the lung

using the coracoid approach.

PB, Nowitz M. A magnetic resonance imaging analysis of the

infraclavicular region: can brachial plexus depth be estimated before

needle insertion? Anesth Analg 2005;100:1184–1188.

J. The infraclavicular brachial plexus block by the coracoid approach

is clinically effective: an observational study of 150 patients. Can J Anaesth 2003;50:253–257.

O, Lilleas FG, Rotnes JS, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging

demonstrates lack of precision in needle placement by the

infraclavicular brachial plexus block described by Raj et al. Anesth Analg 1999;88:593–598.

H, Mayfield J, Rosow L, Chang Y, Carter C, Rosow C. Stimulation of the

posterior cord predicts successful infraclavicular block. Anesth Analg 2006;102:1564–1568.

V, Asehnoune K, Chassery C, et al. Resident versus staff

anesthesiologist performance: coracoid approach to infraclavicular

brachial plexus blocks using a double-stimulation technique. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2005;30:233–237.

V, N’guyen L, Chassery C, et al. A modified coracoid approach to

infraclavicular brachial plexus blocks using a double-stimulation

technique in 300 patients. Anesth Analg 2005;100:2263–2265.

J, Barcena M, Alvarez J. Restricted infraclavicular distribution of the

local anesthetic solution after infraclavicular brachial plexus block. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2003;28:33–36.

J, Barcena M, Taboada-Muniz M, et al. A comparison of single versus

multiple injections on the extent of anesthesia with coracoid

infraclavicular brachial plexus block. Anesth Analg 2004;99:1225–1230.

J, Taboada-Muniz M, Barcena M, Alvarez J. Median versus

musculocutaneous nerve response with single-injection infraclavicular

coracoid block. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2004;29:534–538.

JL, Brown DL, Wong GY, et al. Infraclavicular brachial plexus block:

parasagittal anatomy important to the coracoid technique. Anesth Analg 1998;87:870–873.