Benign Soft Tissue Tumors

by approximately 100:1. In adults, lipomas are the most common soft

tissue tumor; in children, hemangiomas are the most common. Recognition

of these relatively more common benign tumors is important not only to

avoid overtreatment but also to allow distinction from their malignant

counterparts. Soft tissue tumors, both benign and malignant, are

classified according to the purported cell of origin or resemblance,

and the organization of this chapter will follow the latest World

Health Organization (WHO) scheme in that regard.

However, because it is, soft tissue sarcomas are sometimes assumed to

be lipomas, unnecessarily delaying the diagnosis. Hence, recognition of

the distinction between benign lipomas and soft tissue sarcomas is very

important.

-

Etiology is unknown.

-

More common in obese patients

-

Peak age: 40 to 60 (rare in children)

-

Multiple lipomas in 5%

-

Lobules of mature adipocytes

-

Occasionally other areas of tissue formation

-

Bone = osteolipoma

-

Cartilage = chondrolipoma

-

Myxoid change = myxolipoma

-

-

Chromosomal aberrations in up to 75%

-

Three patterns

-

12q13-15 aberrations

-

6p21-23 aberrations

-

Loss of material from 13q

-

-

Histologic variant subtypes have no prognostic significance.

-

Infiltrative

-

Intermuscular: easily shelled out between muscles

-

Intramuscular: two types within muscle

-

Well demarcated

-

Infiltrative: infiltrates and encases atrophic muscle fibers

-

-

Subsynovial located lipoma

-

One type of intra-articular lipoma

-

Most common: painless mass with characteristic doughy feel

-

Most superficial lipomas are small (<5 cm).

-

Most deep lipomas are large (>5 cm).

-

Lipoma arborescens presents as articular swelling.

-

Superficial lipomas: difficult to see on radiographs or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

-

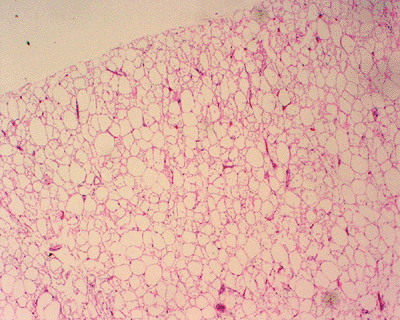

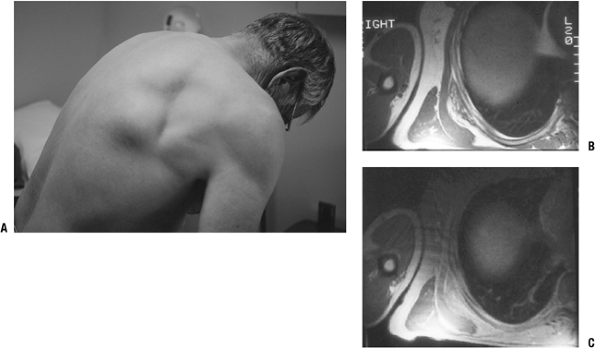

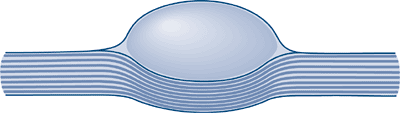

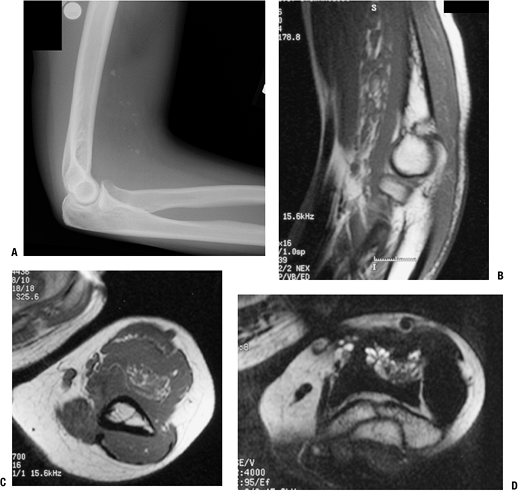

Deep lipomas (Fig. 11-1)

-

Fatty intramuscular shadow

-

Homogeneous fatty signal on all MRI sequences

-

No gadolinium enhancement

-

Occasional entrapped muscle fibers or fibrous strands

-

-

Lipoma arborescens

-

Fatty infiltration throughout affected synovium with fat-distended villi

-

|

|

Figure 11-1 Inramuscular lipoma of the proximal forearm. (A) The fatty soft tissue shadow is shown within the muscle of the proximal forearm by plain radiograph. Axial T1-weighted (B) and T2-weighted (C) MR imaging studies show homogenous fatty signal characteristics identical to that of the subcutaneous fat.

|

-

Most superficial lipomas are

distinguished by their doughy characteristics on physical examination

and do not warrant radiographic evaluation. -

Larger or deep masses warrant plain radiographic and MRI evaluation, which is usually diagnostic.

-

Biopsy is rarely indicated.

-

Also see Chapter 2, Evaluation of Soft Tissue Tumors.

-

Superficial lipomas

-

Observation favored

-

Excision only if symptomatic

-

-

Deep lipomas

-

Observation if radiology identifies clearly as benign lesion (not atypical lipoma or liposarcoma)

-

Excision for most

-

-

Marginal excision (complete excision through pseudocapsule)

-

Avoid transaction of nerves running within deep lipomas (piecemeal excision preferred).

-

Rarely recur following marginal excision

its distribution. Lipomatosis should be distinguished from lipomas, as

the former conditions may be correctable by addressing the underlying

condition and tend to recur after attempted excision.

-

Etiology is poorly understood.

-

Possibly due to point mutations in mitochondrial genes

-

See Table 11-1 for epidemiology.

-

Histopathology: mature fat in poorly circumscribed lobules or sheets infiltrating surrounding tissues

-

Classified by distribution for idiopathic types (diffuse, pelvic, symmetric) or by etiology (steroid, HIV lipodystrophy)

-

Notable accumulations of fat in affected areas may resemble neoplasms (see Table 11-1).

-

Radiologic studies document extent of fatty deposition.

-

Neither radiological evaluation nor biopsy is usually necessary to diagnosis the lipomatoses.

-

See Chapter 2.

-

Palliative surgery is rarely indicated

unless life-threatening fat accumulation (such as that causing

laryngeal compression in Madelung’s disease). -

Correction of steroid lipomatosis follows lowering of steroid levels.

|

Table 11-1 Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Lipomatosis Subtypes

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

lipofibromatous hamartoma, fibrolipomatosis, and intraneural lipoma,

among other names, is a fatty and fibrous infiltrative process

affecting the epineurium and leading to enlargement of the affected

nerve. The median and ulnar nerves are most commonly affected.

-

Etiology is unknown.

-

Peak age: 10 to 40

-

Frequently evident at birth or early childhood

-

Female > male if macrodactyly present; male > female if none

-

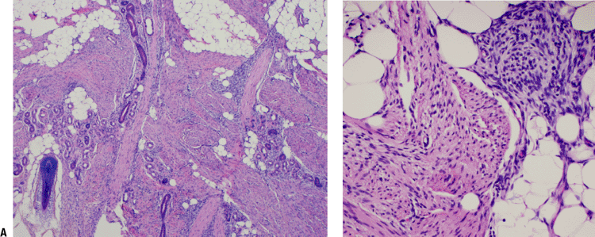

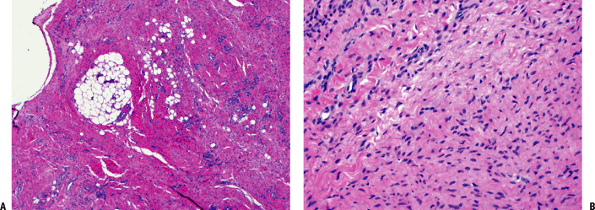

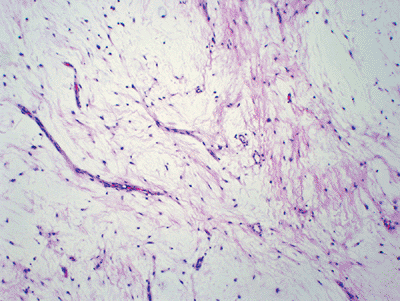

Gross histopathology: yellow fibrofatty infiltration of nerve (Fig. 11-2)

-

Microscopic histopathology: epineurial and perineural fibrofatty infiltration isolating individual nerve bundles

-

Gradually enlarging mass with variable neurologic deficits

-

Median nerve or branches > ulnar nerve

-

Foot, brachial plexus less common sites

-

Macrodactyly in one third

|

|

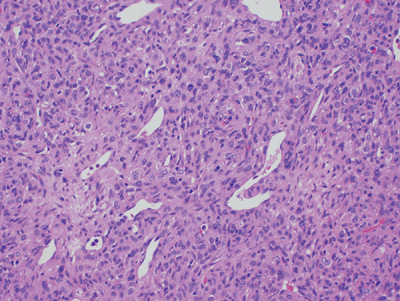

Figure 11-2 A

Fibrous hamartoma of infancy. Organoid pattern composed of intersecting fascicles of spindle cells separated by collagen, mature fat, and islands of immature mesenchymal cells with myxoid matrix. B Close-up view of characteristic island of immature mesenchyma in fibrous hamartoma of infancy. |

-

MRI findings pathognomonic

-

Fusiform neural enlargement following branching pattern of nerve

-

Hypointense serpentine nerve bundles on both T1- and T2-weighted images

-

Variable intramuscular fatty deposition

-

-

Because MRI is diagnostic, biopsy is usually not needed.

-

Goal of surgical intervention is to decompress nerve if symptomatic.

-

Avoid attempted excision, which may damage nerve.

that occurs predominately in infants and may be localized

(lipoblastoma) or diffuse (lipoblastomatosis). Since lipomas generally

do not occur in this age group, lipoblastoma should be considered

highly in the differential diagnosis of any tumor with fatty imaging

characteristics in a child.

-

Etiology is unknown.

-

Peak age: birth to age 3; less common in older children

-

Males > females

-

Variable mixture of mature adipocytes and immature fat cells (lipoblasts)

-

Variable myxoid background with plexiform vascular pattern suggestive of myxoid liposarcoma

-

Pronounced lobular pattern and lack of atypia distinguishes lipoblastoma from liposarcoma

-

8q11-13 rearrangement in most cases

-

Fusion gene products: HAS2/PLAG1, COL1A2/PLAG1

-

Solitary (lipoblastoma) versus diffuse (lipoblastomatosis)

-

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

-

Sites: extremities predominate

-

Typically small (2 to 5 cm), superficial mass

-

Lipoblastomatosis often involves muscle as well.

-

Fatty signal characteristics

-

Bright on T1-weighted MRI, dark on fat-suppressed sequences, identical to surrounding fat

-

-

Indistinguishable from lipoma, well-differentiated liposarcoma (atypical lipoma) by radiology

-

Lipoblastoma: marginal en bloc excision

-

Lipoblastomatosis: wide surgical excision

-

Recurrence rare in lipoblastoma; up to 22% in lipoblastomatosis

|

Table 11-2 Histological Lipoma Variants

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

extremity and neck region that is distinguished by its rapid growth and

its tissue culture–like histology pattern.

-

Etiology: unknown, but history of trauma common

-

Peak age: young adults, but may involve any age

-

Plump, regular myofibroblasts

-

Frequent mitoses but not atypical mitoses

-

Tissue culture–like, “torn” or “feathery” appearance at low power

-

Prominent small vessels may resemble granulation tissue.

-

Nodular infiltrative pattern of organization

-

Extravasated red blood cells, chronic inflammatory cells, and even giant cells may be seen.

-

SMA and MSA positive

-

Desmin, cytokeratin, and S100 negative

|

|

Figure 11-3

Angiolipoma composed of mature adipose tissue intermixed with numerous vascular channels. The vascularity is often more prominent in subcapsular areas. |

|

|

Figure 11-4

Hibernoma: rare fatty tumor composed of mature adipose tissue and a large number of multivacuolated brown fat cells with abundant granular cytoplasm and a centrally located nucleus. |

-

Some clonality suggesting neoplastic nature demonstrated, but may represent artifact of culture conditions

-

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

-

Subcutaneous >> intramuscular

-

Upper extremity, trunk, head and neck most common

-

Rapid growth is characteristic.

-

Clinical history usually <1 to 2 months

-

Pain and local tenderness common

-

Small size, usually <2 cm

|

|

Figure 11-5

Nodular fasciitis: cellular proliferation of stellate cells with vague storiform pattern and extravasated red blood cells. Inflammatory cells and mitoses are also commonly seen, but there is no cytologic atypia. |

-

Nonspecific soft tissue mass (Fig. 11-6)

-

Marginal excision

-

Rare recurrence should warrant reconsideration of diagnosis.

their rapid growth, predilection for the upper extremity, and plump

myofibroblastic cells, but they are distinguished by the large

ganglion-like cells that are also present. Proliferative fasciitis (PF)

involves the fascia, while proliferative myositis (PM) involves the

muscle.

-

Etiology is unknown, although a history of trauma may be elicited.

-

Peak age: middle-aged or older adults, older than nodular fasciitis

-

Much less common than nodular fasciitis

-

Two cellular types: plump myofibroblasts and ganglion-like cells

-

Plump myofibroblasts resemble those of nodular fasciitis.

-

Ganglion-like cells: large with one to three rounded nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant cytoplasm

-

Numerous mitoses but not atypical mitoses

-

Infiltrative growth pattern (along fascial planes for PF and between muscle groups in PM)

-

Checkerboard pattern of infiltration between muscle fibers for PM

-

SMA and MSA positive

-

Desmin, cytokeratin, and S100 negative

-

Similar to nodular fasciitis

-

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

-

PF: upper extremity (especially forearm) > lower extremity > trunk

-

PM: trunk > shoulder girdle > upper arm > thigh

-

Rapid growth is characteristic.P.269

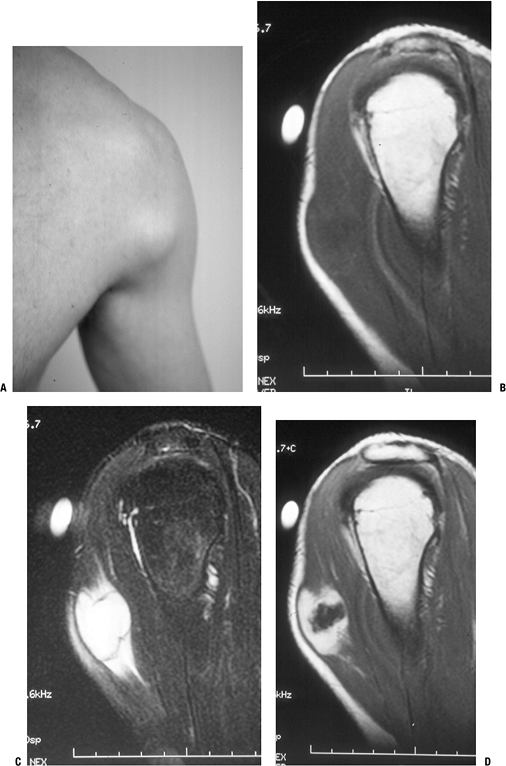

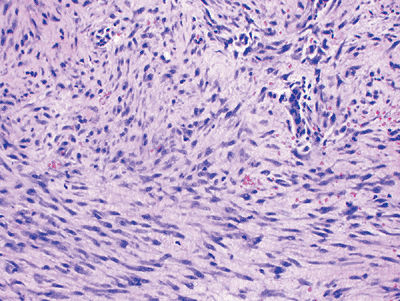

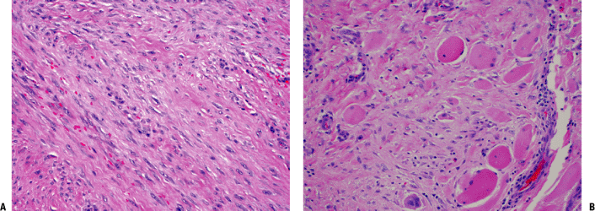

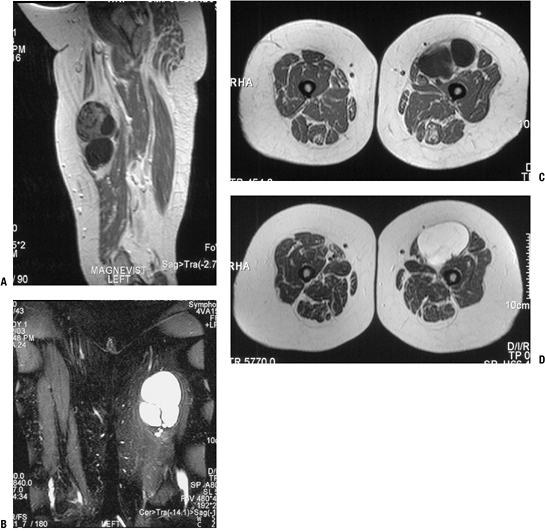

![]() Figure 11-6 Nodular fasciitis of the shoulder. (A)

Figure 11-6 Nodular fasciitis of the shoulder. (A)

The patient presented with a 3-week history of a rapidly enlarging,

painful soft tissue mass over the anterior deltoid. Sagittal MR studies

show nonspecific findings of a heterogeneous intramuscular mass

hypointense to muscle on T1-weighted sequences (B), hyperintense on T2-weighted images (C), and enhancing on post-gadolinium sequences (D). -

Clinical history usually <1 or 2 months

-

Pain and local tenderness more common with PF

-

Small size, usually <5 cm

-

Nonspecific soft tissue mass

-

Marginal excision

-

Recurrence is rare.

characterized by bone formation within the soft tissues in response to

trauma. On the one hand, it may simulate malignancy, but conversely,

sarcomas that give a similar appearance may be mistaken for this

benign, self-limited condition.

-

Trauma history elicited in up to 75% of patients; repetitive trauma in others

-

Peak age: young, physically active adults (rare in infants or elderly)

-

Males > females

-

Zonal proliferation with central fibroblasts and peripheral osteoblast-rimmed bone trabeculae

-

Progression from initially fibrous tissue to peripheral woven bone and then eventually lamellar bone

-

Peripheral ossification usually evident by 3 weeks

-

Mitoses frequent but no atypical mitoses

-

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

-

Initial 1 to 2 weeks after injury: swollen, tender

-

From 2 to 6 weeks after injury: tenderness and pain resolve, and painless, very firm mass forms

-

Chronically, the mass becomes less prominent over time.

-

Any location in body susceptible to trauma

-

Most common locations: thigh, shoulder, buttock, elbow

-

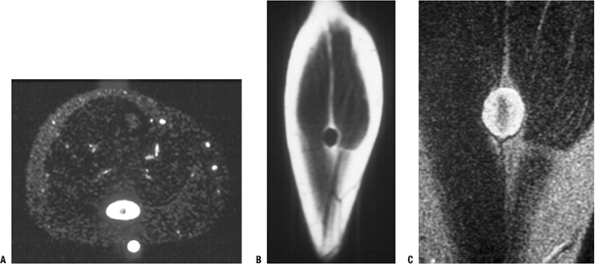

Initial 1 to 2 weeks after injury: x-ray,

computed tomography (CT), MRI shows soft tissue shadow, heterogeneous

MRI signal with edema -

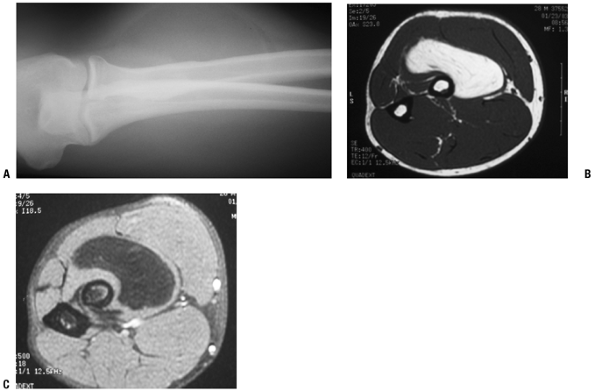

From 2 to 6 weeks after injury: x-ray, CT best show peripheral rim of calcifications (Fig. 11-7)

-

Chronically, MRI eventually shows low-signal rim with fatty marrow signal centrally.

-

Observation is best, but marginal excision is appropriate if sufficiently symptomatic.

-

May recur if excised incompletely early in course

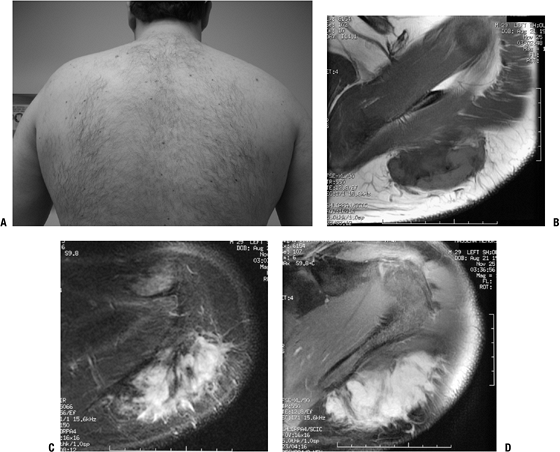

that occurs almost exclusively in a subscapular location in adults and

is characterized by histologic evidence of elastic fibers.

-

Etiology is unknown, although repetitive trauma has been implicated.

-

Peak age in seventh and eighth decades (nearly always after age 50)

-

Females > males

-

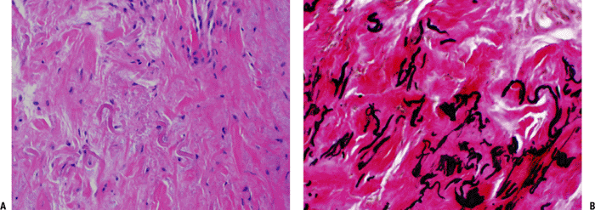

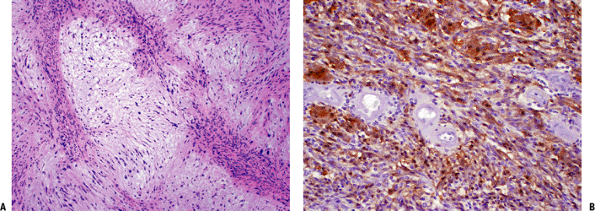

Low-cellularity collagenous tissue with intermixed elastic fibers (Fig. 11-8)

-

Immunohistochemistry positive for elastin

-

Familial occurrence reported in Okinawa

-

Slowly growing mass, typically painless and nontender

-

May cause popping scapula or local discomfort

-

Classic location

-

Nearly exclusively subscapular, applied to chest wall at the lower portion of the scapula

-

Deep to latissimus dorsi and rhomboid major

-

Often attached to periosteum of ribs

-

Rare musculoskeletal sites: upper arm, hip

-

May be bilateral (especially subclinical) in up to one third

-

-

Fibrous and fatty elements create layered picture.

-

MRI may be highly suggestive (Fig. 11-9).

-

Fatty areas: bright areas on T1-weighted images, intermediate on T2-weighted images

-

Fibrous areas: similar to muscle

-

-

Biopsy is generally recommended to

confirm diagnosis, although the combination of classic location and

radiologic appearance is highly suggestive. -

Also see Chapter 2.

|

|

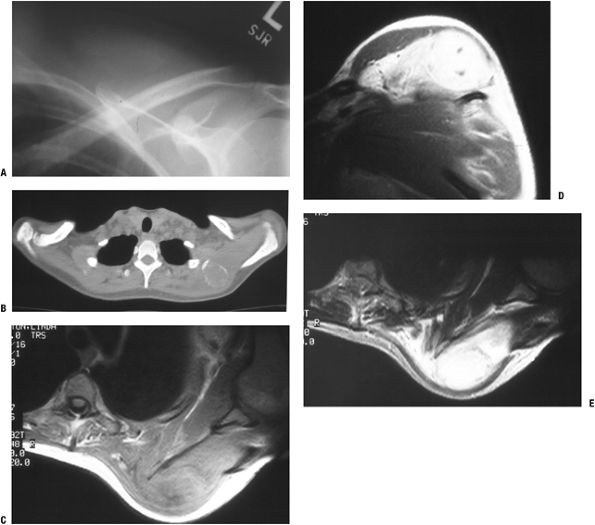

Figure 11-7 (A)

Initial plain radiographs within the first 2 to 3 weeks may not show the characteristic peripheral rim of calcification associated with myositis ossificans. (B) Subsequently, the peripheral rim is best demonstrated on computed tomography. (C) MR studies show a heterogeneous mass that is sometimes confused with a soft tissue sarcoma. |

-

Marginal excision indicated for symptomatic patients but may be observed if asymptomatic and histologically proven

-

Rarely recurs after complete excision

(Dupuytren’s disease or contracture) and plantar fibromatosis

(Ledderhose disease), both fibroblastic proliferations with

infiltrative growth that are usually easily recognizable clinically and

have a high rate of local recurrence if excised.

-

Etiology is multifactorial.

-

Familial component

-

Trauma

-

Associated diseases: epilepsy, diabetes, alcohol- induced liver disease

-

-

Peak age: adults with increasing frequency in advanced ages (rare before age 30)

-

Males >> females (3 to 4:1)

-

Pathophysiology is shown in Figure 11-10.

|

|

Figure 11-8 (A) Elastofibroma composed of intertwining, swollen collagen and elastic fibers with fibroblasts. (B) Elastic fibers highlighted by EVG stain in elastofibroma.

|

-

Palmar fibromatosis

-

Volar surface, 50% bilateral

-

Typical progression

-

Begins with firm painless nodule

-

Progresses to multiple nodules connected by tight cords (distinguished from pre-existing normal fascial bands)

Figure 11-9 (A)

Figure 11-9 (A)

The characteristic location for an elastofibroma is at the inferior

medial border of the scapula in a subscapular position. MR images show

a heterogeneous subscapular soft tissue mass on T1-weighted (B) and proton density (C) axial images. -

Puckering of overlying skin

-

End-stage flexion contractures favoring ring and little fingers

-

-

-

Plantar fibromatosis

-

Plantar aponeurosis

-

Typical course

-

Begins with firm nodule adherent to skin

-

Often painful with shoe wear

-

Progressive enlargement may result.

-

Rarely leads to contracture

-

-

|

|

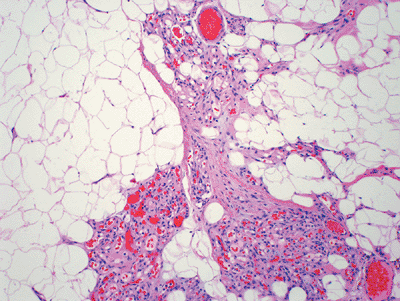

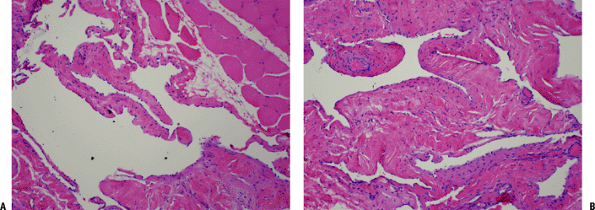

Figure 11-10 (A) Plantar fibromatosis: dense fibrous proliferation infiltrating adipose tissue. (B)

Plantar fibromatosis: early lesions consist of cellular proliferations of bland-looking spindle cells and collagen deposition similar to desmoid tumors. Older lesions tend to be less cellular and contain more collagen. |

-

Palmar fibromatosis

-

Cords and hypocellular nodules dark on T1- and T2-weighted images

-

Hypercellular nodules intermediate on T1- and T2-weighted images

-

-

Plantar fibromatosis

-

Isointense to slightly hyperintense always on T1-weighted images and nearly always on T2-weighted images

-

Usually hyperintense on short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequence

-

Enhancement common

-

-

Dupuytren’s contracture and many cases of

plantar fibromatosis are easily recognized clinically and do not

require either further imaging or biopsy. -

If plantar masses are not characteristic, MRI imaging may establish the diagnosis, but biopsy is sometimes needed.

-

Palmar fibromatosis

-

Flexion contracture is most common indication for operative treatment.

-

Details of operative treatment are beyond the scope of this text.

-

-

Plantar fibromatosis

-

Usually managed nonoperatively unless recalcitrant to adaptive shoe wear and inserts

-

If operative treatment is elected, complete fasciectomy achieves lowest recurrence rates.

-

High recurrence rate for plantar fibromatosis ranging from 50% with complete fasciectomy to 100% with local excision

-

interest in orthopaedics. They consist of a neoplastic fibroblastic

proliferation that may result in pain, infiltrative growth resulting in

recurrence, and absence of metastatic potential.

-

Familial component

-

Component of Gardner syndrome (autosomal dominant transmission, variant of familial adenomatous polyposis; Box 11-1)

-

-

Endocrine factors

-

Frequent exacerbation/appearance postpartum

-

Estrogen receptors in desmoid tumors

-

Response to endocrine agents

-

-

Trauma may be contributory factor.

-

Pediatric patients: extra-abdominal > abdominal

-

Puberty to 40: abdominal > extra-abdominal, female > male

-

Older than 40: abdominal = extra-abdominal

-

Gastrointestinal polyps with 100% risk of malignancy

-

Multiple osteomas

-

Epidermoid cysts

-

Desmoid tumors

-

Other benign skin and soft tissue tumors

|

|

Figure 11-11 (A) Extra-abdominal fibromatosis showing a proliferation of bland-looking spindle cells separated by collagen. (B) Infiltration of surrounding soft tissues in fibromatosis. Note the presence of entrapped skeletal muscle cells.

|

-

Low-cellularity spindle cells in collagenous stroma

-

Extremely infiltrative process arranged in sweeping bundles

-

Two mutations with common endpoint of increased beta-catenin expression

-

Inactivation of APC tumor suppressor gene on 5q may be initiating event, especially those with familial occurrence.

-

Activating beta-catenin mutations render beta- catenin resistant to inhibitory effect of APC.

-

-

Trisomies for chromosomes 8 or 20 in 30% of cells

-

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

-

Deep (as distinguished from superficial fibromatoses)

-

Painful or painless, poorly circumscribed, very hard mass

-

Occasionally multifocal

-

Occasional joint stiffness or neurological symptoms

-

MRI nonspecific (Fig. 11-12)

-

Isointense to muscle on T1-weighted images

-

Intense contrast enhancement

-

Hyperintense on STIR and T2-weighted images

-

-

Surgical indication

-

Wide resection preferred if adequate margin attainable with acceptable function

-

-

Surgical contraindications

-

Vital structures involved or unresectable disease

-

Consider alternative treatments in this situation:

-

Radiotherapy

-

Pharmacologic treatment

-

Hormonal agents

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents

-

Interferons

-

Cytotoxic chemotherapy

-

-

-

-

Radiotherapy consultation is recommended for positive surgical margins, although efficacy not well established.

-

Surgical resection

-

Wide margins: 85% to 90% local control

-

Marginal margins: 50%

-

Intralesional margin: <50%

-

-

Radiotherapy

-

Typically recommended for positive margins, but proof of efficacy not clearly established

-

-

Pharmacologic treatment

-

40% to 50% response rate

-

solitary fibrous tumors (SFT) and hemangiopericytoma (HP) share enough

clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical features to be

classified together and may actually represent a spectrum of the same

entity. They typically behave in a benign fashion, but up to 30% are

malignant.

-

Etiology is unknown.

-

Peak age 20 to 70 years (median 50)

|

|

Figure 11-12 (A)

Desmoid tumor typically presents as a slow-growing, sometimes painful soft tissue mass. MR imaging shows nonspecific hypointense signal on T1-weighted sequences (B) and hyperintense signal on T2-weighted sequences (C). (D) Gadolinium enhancement is intense. |

-

SFT

-

Intermixed hypercellular and hypocellular areas separated by bands of hyalinized collagen

-

Round to spindle cells with indistinct cytoplasm

-

Immunohistochemistry

-

Vimentin, CD34, and CD99 positive

-

Variable focal positivity for others

-

-

-

HP

-

Similar to SFT with addition of prominent variably branching thin-walled vessels with staghorn configuration (Fig. 11-13)

-

Immunohistochemistry

-

Vimentin, CD34, and CD99 positive

-

Cytokeratin, actin, and desmin negative

-

-

|

|

Figure 11-13

Hemangiopericytoma: cellular neoplasm composed of spindle and round cells with large vascular spaces with a “staghorn” configuration. |

-

Inconsistent chromosomal aberrations

-

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

-

Superficial or deep, slowly growing, small or large, painless mass in any location

-

Rare paraneoplastic syndrome due to IGF-1

production results in hypoglycemia or acromegaly; oncogenic

osteomalacia is very rare with these tumors.

-

Nonspecific radiologic features

-

MRI nonspecific

-

Isointense to slightly hyperintense on T1-weighted images

-

Hyperintense on T2-weighted images

-

Heterogeneous, enhancing

-

-

Wide surgical resection

-

Postoperative management with adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy may play a role in some malignant cases.

-

85% 5-year survival rate including malignant forms

tumor or nodular tenosynovitis, these common tumors represent the most

common neoplasms of the hand. In some classifications, such as that of

the current WHO, this terminology also includes what in the past has

been referred to as the localized form of pigmented villonodular

synovitis (PVNS).

|

|

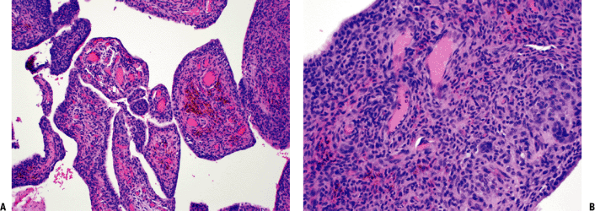

Figure 11-14 (A)

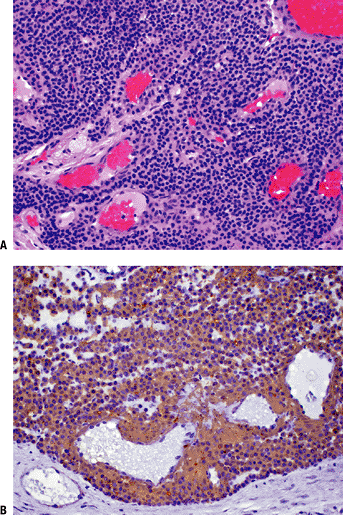

Pigmented villonodular synovitis showing characteristic intra-articular villous pattern. Abundant hemosiderin pigment seen within macrophages in fibrovascular core. (B) Pigmented villonodular synovitis: solid areas composed of oval to spindle-shaped, histiocytoid, mononuclear cells and multinucleated giant cells. |

-

Current evidence favors a neoplastic etiology over the traditional belief that this was a reactive process.

-

Peak age: 30 to 50 years (but any age may be involved)

-

Female > male

-

Grossly well circumscribed with yellow and brown areas

-

Composed of mixture of background

mononuclear cells, variable numbers of giant cells, lipid-laden

xanthoma cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages -

Immunohistochemistry

-

Mononuclear cells: CD68 positive

-

Giant cells: positive for CD68, CD45, and tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)

-

-

Cytogenetic aberrations of chromosome 1p in particular, frequently with translocation, are common.

-

No trisomies of chromosomes 5 or 7, as seen with PVNS

-

Predominately in the hand (85%) near tendon sheath or joint > wrist, foot/ankle, knee

-

Small painless nodules

-

Approximately 20% erode adjacent bone.

-

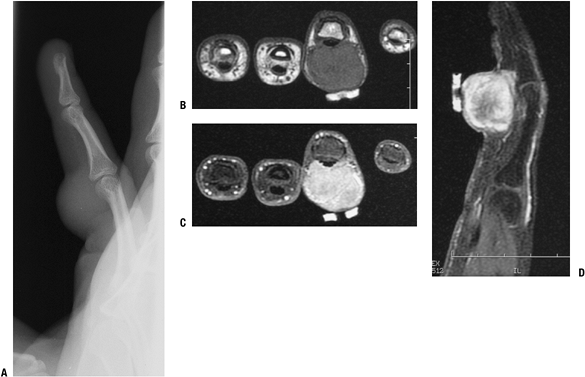

Nonspecific MRI features (Fig. 11-15)P.277

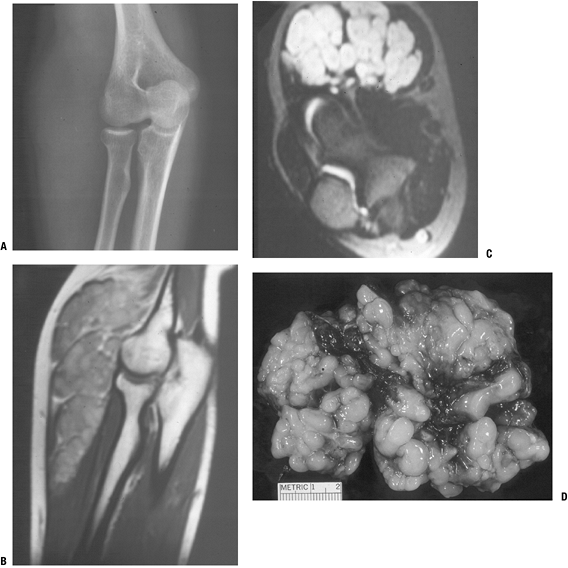

Figure 11-15 Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath shows a soft tissue shadow on plain lateral radiograph (A), hypointense signal on axial T1-weighted MRI (B), hyperintense signal on axial T2-weighted MRI (C), and gadolinium enhancement on post-contrast fat-suppressed T1-weighed sagittal MRI (D).

Figure 11-15 Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath shows a soft tissue shadow on plain lateral radiograph (A), hypointense signal on axial T1-weighted MRI (B), hyperintense signal on axial T2-weighted MRI (C), and gadolinium enhancement on post-contrast fat-suppressed T1-weighed sagittal MRI (D).-

T1-weighted images: hypointense to slightly hyperintense to muscle

-

T2-weighted images: hypointense to hyperintense to muscle

-

Heterogeneous due to hypointense areas

-

Diffuse contrast enhancement

-

-

Usually plain radiographs and MRI are sufficient for these small masses.

-

Also see Chapter 2.

-

Marginal excision

-

Up to 30% recurrence rate, easily controlled by re-excision

proliferative synovial process predominately seen affecting the knee.

It was formerly subdivided into localized and diffuse forms; the former

is now classified as localized giant cell tumor.

-

Current evidence favors a neoplastic etiology over the traditional belief that this was a reactive process.

-

Peak age: <40 years (but any age may be involved)

-

Female > male

-

Intra-articular forms: villous pattern with yellow and brown areas (Fig. 11-14A)

-

Extra-articular forms: grossly well circumscribed with yellow and brown areas (Fig. 11-14B)

-

Expansile sheets of infiltrative cells

with intermixed cellular regions and discohesive areas creating

blood-filled pseudoalveolar spaces -

Composed of mixture of background

mononuclear cells, variable numbers of giant cells, lipid-laden

xanthoma cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages-

Giant cells less common than in giant cell tumor of tendon sheath, sparse or absent in up to 20%

-

Bimodal mononuclear cells: small histiocyte-like cells and larger dendritic cells

-

-

Immunohistochemistry

-

Mononuclear cells: CD68 positive

-

Larger dendritic cells: desmin positive

-

Giant cells: CD68, CD45, and TRAP positive

-

-

Chromosome 1p translocations common and similar to giant cell tumor of tendon sheath

-

Trisomies of chromosomes 5 and 7 seen only in PVNS, not in giant cell tumor of tendon sheath

-

Intra-articular and extra-articular forms

-

Usually large and associated with pain, local tenderness, and decreased joint motion

-

Recurrent hemarthroses common

-

Juxta-articular erosions evident in intra-articular form in advanced cases

-

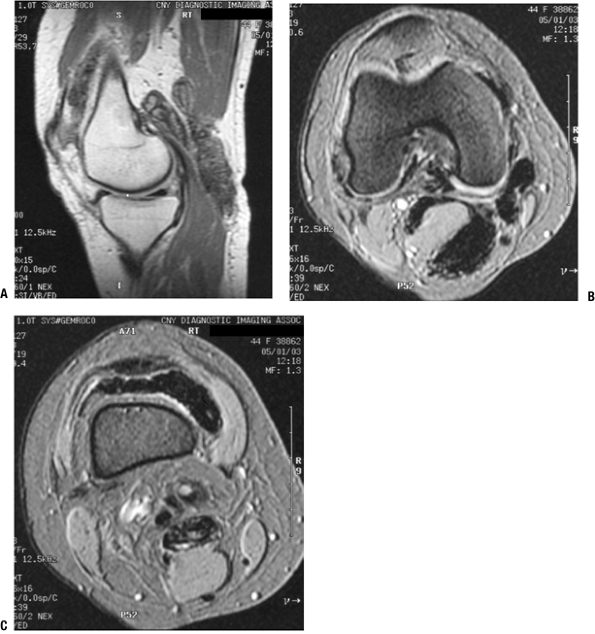

MRI

-

Characteristic hemosiderin attenuation of signal resulting in at least foci of hypointense signal within all sequences

-

Fatty areas due to lipid accumulation

-

Joint effusion

-

|

|

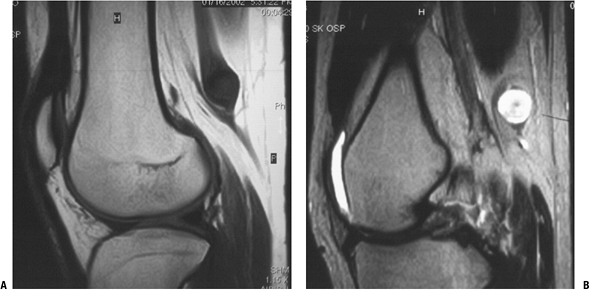

Figure 11-16

Pigmented villonodular synovitis shows characteristic signal attenuation from the hemosiderin deposition within the synovium on all MRI sequences. In this case, low-signal areas can be seen within the suprapatellar pouch and popliteal region on these sagittal T1-weighted (A), axial proton density (B), and axial T2-weighted (C) MR images. |

-

Usually plain radiographs and MRI are sufficient for these processes.

-

Also see Chapter 2.

that may occur as solitary lesions or as a component of

neurofibromatosis. Neurofibromas are more characteristically

intertwined with the peripheral nerve and difficult to separate.

-

Etiology is unknown.

-

Peak age: young adults 20 to 30 years

|

|

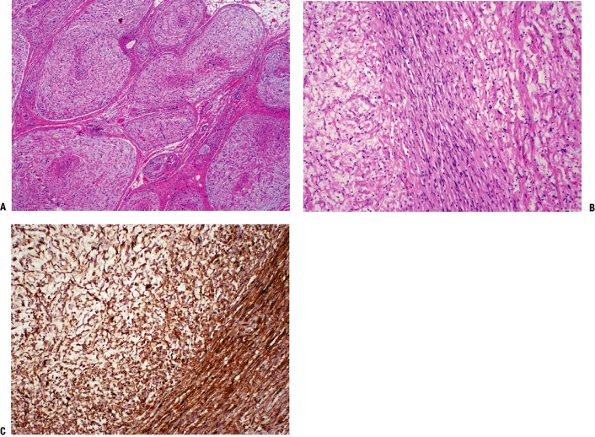

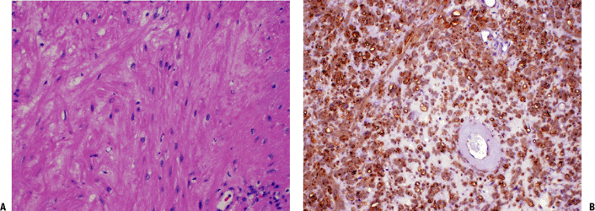

Figure 11-17 (A) Cross-section of a plexiform neurofibroma showing its distinctive arrangement in large fascicles. (B)

Characteristic neurofibroma with wavy spindle cells in a loose stroma. Toward the center, cells are more tightly apposed, resembling peripheral nerve fibers. (C) Diffuse and strong immunostaining of neurofibroma with S-100 protein stain. |

-

Mixture of Schwann cells, perineurial-like cells, and fibroblasts

-

Hypocellular, widely spaced cells with thin, elongated nuclei

-

S100 positive

-

NF-1 gene mutation in neurofibromatosis (NF)

-

Solitary neurofibromas not as clearly established

-

Localized cutaneous neurofibroma (Fig. 11-18)

-

Most common type

-

10% occur in NF-1

-

-

Diffuse cutaneous neurofibroma

-

Plaque-like thickenings of dermis and subcutaneous tissue

-

-

Localized intraneural neurofibroma (Fig. 11-19)

-

Second most common type

-

Fusiform segmental enlargement of nerve (Fig. 11-20)

P.280Table 11-3 Subtypes of NeurofibromaSubtype Depth Site Size Pain? % in NF-1 Malignant Transformation? Diffuse cutaneous neurofibroma Skin and subcutaneous Any 1 to 2 cm No 10% No Localized cutaneous neurofibroma Skin and subcutaneous Head and neck Several centimeters No 10% Rare Localized intraneural neurofibroma Superficial or deep In NF-1, predilection for cervical spine 1 cm to many centimeters Neural pain if deep Minority Infrequent Plexiform neurofibroma Usually deep Predilection for larger nerves Large Neural pain Almost exclusively Highest Massive soft tissue neurofibroma Skin and deeper tissues Shoulder, pelvis, lower extremity Large Variable 100% Rare -

-

Plexiform neurofibroma (Fig. 11-21)

-

Uncommon tumor usually affecting large nerve

-

“Bag of worms” appearance in plexus regions (Fig. 11-22)

-

Firm, ropy cylinder in nonbranching nerves

-

Highly suggestive of diagnosis of NF-1

-

-

Massive soft tissue neurofibroma (Fig. 11-24)

-

Least common form always seen in NF-1

-

Formerly called “elephantiasis neuromatosa”

-

Localized gigantism or massive regional tissue enlargement

-

-

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

|

|

Figure 11-18

Localized cutaneous neurofibromas, as shown in this patient with type I neurofibromatosis, are the most common type of neurofibroma. |

-

Solitary painless or painful masses or in the setting of NF-1 (von Recklinghausen’s disease)

-

Intraneural neurofibromas may cause pain or paresthesias along distribution of affected nerve.

-

Tinel’s sign may be positive.

-

More medial–lateral movement than proximal– distal on palpation

-

-

MRI features may be highly suggestive of benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors.

-

Target sign more frequent with neurofibromas than schwannomas (Fig. 11-25)

-

Dark on T1-weighted images, bright on T2-weighted images

-

-

Dumbbell tumors (partially intraspinal and partially extraspinal) may cause foraminal enlargement.

-

Localized cutaneous neurofibroma and diffuse cutaneous neurofibroma

-

Excision usually curative

-

No neurological deficit expected

-

-

Localized intraneural neurofibroma and plexiform neurofibroma

-

Avoid resection due to need to resect functional nerve fibers.

-

Indications for excision: suspicion for malignant degeneration

-

Rapid increase in size

-

Pain

-

-

-

Massive soft tissue neurofibroma

-

May be amenable only to debulking

-

|

|

Figure 11-19

Localized intraneural neurofibroma is usually recognizable as a benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor, but it may be difficult to distinguish from a schwannoma. This case shows a discrete enhancing mass in continuity with deep nerve fibers on coronal T1-weighted (A), post-gadolinium T1-weighted (B), and axial T2-weighted (C) images. Although these features could be seen with either neurofibroma or schwannoma, this tumor was found to be a neurofibroma histologically. |

|

|

Figure 11-20

Schematic shows appearance of an intraneural neurofibroma, where normal nerve fibers entering and exiting the tumor are intimately intertwined with those of the neurofibroma. |

|

|

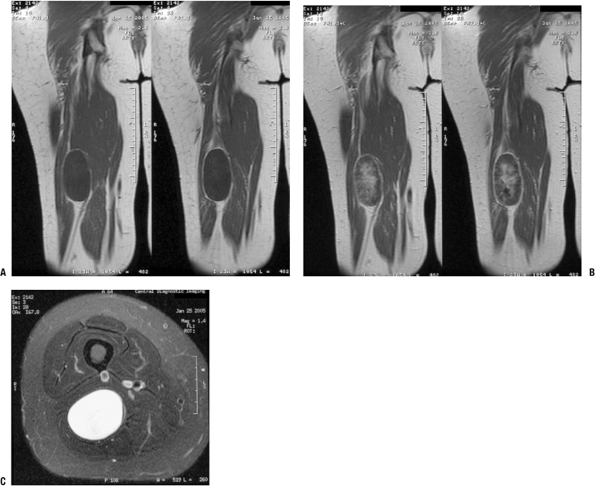

Figure 11-21

Plexiform neurofibroma, which is highly suggestive of the diagnosis of type I neurofibromatosis, is shown here as the classic “bag of worms” appearance on plain radiograph (A), MR images (B,C), and gross resected specimen (D). |

|

|

Figure 11-22 Schematic shows typical “bag of worms” appearance of a plexiform neurofibroma.

|

|

|

Figure 11-23 Schematic shows typical eccentric position of a neurilemoma, where normal nerve fibers are displaced peripherally by the mass.

|

|

|

Figure 11-24 Massive soft tissue neurofibroma is manifest in this leg as a bag-like collection.

|

|

|

Figure 11-25 (A)

The target sign of peripheral nerve sheath tumors on an axial MR image for a neurofibroma, which more commonly shows this sign than does schwannoma. Coronal T1-weighted (B) and T2-weighted (C) images. |

most common benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors. While there are four

histological variants, this section will concentrate on the

conventional schwannoma.

-

Etiology is unknown.

-

Peak ages: third to sixth decades

-

A schwannoma is a neoplasm composed of Schwann cells, and its immunohistochemical and ultrastructural profile reflects that.

-

Biphasic Antoni A and B areas

-

Antoni A pattern

-

Collagenous background

-

Compact, elongated spindle cells aligned in bundles

-

Verocay bodies: palisaded arrangement of peripheral aligned nuclei surround central eosinophilic cell processes

-

-

Antoni B pattern

-

Mucopolysaccharide myxoid background

-

Less organized cells with plump nuclei and delicate cobweb-like interconnecting processes

-

-

-

Cystic degeneration and hemorrhage frequent (formerly termed “ancient schwannoma”)

-

Immunohistochemistry: S100 positive

-

Not associated with NF-1 but may be associated with NF-2

|

|

Figure 11-26 (A)

Schwannoma with characteristic areas of high cellularity (Antoni A) and low cellularity (Antoni B). Note the palisading of spindle cells known as Verocay bodies. (B) Strong immunoreactivity of schwannoma cells with S-100 protein stain. |

-

Conventional: most common form; characterized by Antoni A and Antoni B areas

-

Cellular: higher cellularity, mostly Antoni A areas, absent Verocay bodies

-

Plexiform: rare variant with intraneural pattern but not usually associated with NF-1

-

Melanotic: unusual variant with melanin-producing cells

-

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

-

Head and neck, flexor surfaces of extremities (Fig. 11-27)

-

Slowly growing masses <10 cm

-

May elicit neural symptoms of pain or paresthesias

-

Physical examination may show positive Tinel sign, limited proximal–distal mobility.

-

Spinal schwannomas usually affect sensory nerves.

-

Well-demarcated soft tissue masses on plain x-ray

-

MRI heterogeneity related to cystic degeneration

-

Hypointense on T1-weighted images, hyperintense on T2-weighted images

-

Enhancing

-

-

Target sign on MRI less common than neurofibroma

-

Foraminal enlargement with dumbbell schwannomas and giant sacral schwannomas

-

Marginal complete excision usually

possible without resecting nerve due to eccentric growth (unlike

intraneural and plexiform neurofibromas; Fig. 11-23) -

Recurrence unusual except in sacral schwannomas

|

|

Figure 11-27 Schwannomas of the extremity typically occur on the flexor surface near a joint, such as the knee in this patient.

|

|

|

Figure 11-28 Schwannomas are hypointense to muscle on T1-weighted MR image (A) and hyperintense on T2-weighted image (B). Note how the nerve fibers splay around the round to oval mass.

|

|

|

Figure 11-29 The schwannoma is usually easily separable from the associated nerve, unlike the intraneural neurofibroma.

|

normal-appearing smooth muscle cells, but it is extremely rare in the

extra-abdominal soft tissues.

-

Etiology is unknown.

-

Extremely rare

-

Cells resemble smooth muscle cells with

eosinophilic cytoplasm and blunt-ended, cigar-shaped nuclei arranged in

intersecting bundles (Fig. 11-30). -

Immunohistochemistry

-

Positive for actin, desmin, and h-caldesmon

-

S100 negative

-

-

Clinical features: superficial or deep soft tissue masses

-

Radiologic features: frequently calcified, but otherwise non specific

-

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

-

Marginal excision

-

Local recurrence rate ~3%

|

|

Figure 11-30 (A)

Leiomyoma. Fusiform cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm arranged showing a vague fascicular pattern closely resembling normal smooth muscle. (B) Strong and diffuse reactivity for smooth muscle actin stain in leiomyoma. |

-

Etiology is unknown.

-

Very rare

-

Peak ages:

-

Adult form: median 60 years (33 to 80 years)

-

Fetal form: median 4 years

-

-

Lobules of closely packed cells

-

Spider cells (large, polygonal cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm)

-

Cytoplasmic inclusion bodies, cross-striations

-

Immunohistochemistry: MSA, desmin, and myoglobulin positive

-

This section refers only to extracardiac rhabdomyomas at the exclusion of cardiac rhabdomyomas.

-

The extracardiac rhabdomyomas are subdivided into adult and fetal types.

-

Clinical features: head and neck (90%), soft tissue mass

-

Radiologic features are nonspecific.

-

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

|

|

Figure 11-31

Rhabdomyoma. Solid growth of closely packed, large polygonal cells with abundant eosinophilic or granular cytoplasm and eccentrically located nuclei. |

-

Marginal excision

-

Up to 42% local recurrence

are seen in the orthopaedic context predominately as intramuscular

angiomas or less commonly as synovial hemangiomas.

|

|

Figure 11-32 (A) Intramuscular hemangioma. Large vascular channels lined by flat endothelial cells surrounded by skeletal muscle. (B) Hemangioma. Cavernous vascular spaces lined by flat endothelial cells and focally containing red blood cells.

|

-

Although theories of neoplasm, reactive

processes, and malformations have been put forth, these are currently

thought to most likely be simply malformations.

-

Intramuscular angiomas are among the most

common of soft tissue tumors, particularly in adolescents and young

adults, while the other variants are uncommon to rare. -

Intramuscular angiomas have a female predominance.

-

Various combinations of variably thick-walled vascular channels with hemosiderin deposition

-

Variable amounts of fatty tissue within intramuscular angiomas

-

Synovial hemangioma

-

Intramuscular angioma

-

Venous hemangioma

-

Arteriovenous hemangiomas

-

Intramuscular angioma causes classic activity-related fluctuation in size and pain even over the course of a single day.

-

Spongiform, compressible mass

-

Slowly enlarging

-

-

Arteriovenous malformations result in shunting.P.288Table 11-4 Features of Hemangioma Subtypes

Hemangioma Subtype Peak Age Occurrence Most Common Location Clinical Symptoms Synovial hemangioma Children and adolescents Rare Knee Joint swelling and pain, mechanical symptoms Intramuscular angioma Adolescents and young adults Common Deep, thigh Activity-related pain and swelling Venous hemangioma Adults Uncommon Superficial or deep, extremities Soft tissue mass Arteriovenous hemangioma Children and young adults Uncommon Superficial or deep, head and neck > extremities Shunting manifestations -

Physical examination reveals audible bruit, palpable thrill.

-

Clinical manifestations of shunting: limb hypertrophy, heart failure, consumption coagulopathy (Kasabach-Merritt syndrome)

-

-

Plain radiographs may reveal phleboliths.

-

MRI findings typically diagnostic

-

Characteristic serpentine pattern of blood vessels

-

Intermediate on T1-weighted images, bright on T2-weighted images; heterogeneous

-

Intermixed fatty signal on established lesions

-

-

Clinical examination combined with plain

radiographs and MRI is usually diagnostic and obviates the need for

biopsy except in unusual circumstances. -

Also see Chapter 2.

-

Only sufficiently symptomatic lesions

warrant treatment consideration; the remainder should be observed or

treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications and compressive

devices. -

Surgical excision

-

Small synovial and intramuscular hemangiomas amenable to marginal en bloc excision

-

Especially if single expendable muscle involved

-

-

Embolization and sclerotherapy

-

Larger lesions for which surgical excision is not feasible but sufficiently symptomatic to warrant treatment

-

Contraindicated if neurologic symptoms or compression

-

-

Recurrence rate 30% to 50% following excision unless entire involved muscle excised

of the body by hemangioma(s). This may manifest as extensive muscle

involvement or involvement of multiple tissue levels, including skin,

subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and bone.

-

Etiology is unknown.

-

Peak age: adolescents and young adults

-

Histopathology is same as for hemangioma.

-

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

-

Common sites: lower extremity > chest wall > upper extremity

-

Skin involvement may be evident by varicosities.

-

Same symptoms as described for hemangioma

-

Same as for hemangiomas but more extensive (Fig. 11-34)

-

Often too extensive for adequate excision

-

High rate of local recurrence following attempted excision

-

Etiology is unknown.

-

Peak age: birth to childhood

-

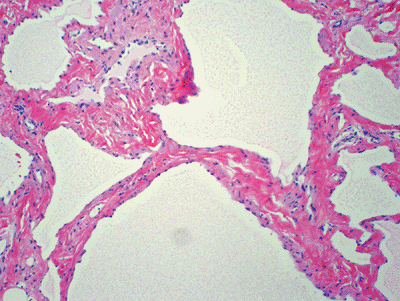

Histopathology: variably sized, thin-walled lymphatic vessels (Fig. 11-35)

-

Genetics: associated with Turner syndrome

|

|

Figure 11-33

This intramuscular hemangioma of the proximal forearm shows classic radiographic features. Phleboliths can be seen on the plain radiograph (A), and the sagittal (B) and axial (C) T1-weighted MR images and axial T2-weighted (D) MR image show serpiginous vascular structures intermixed with fat signal. |

-

Cystic versus cavernous subtypes

-

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

-

Cystic: neck, axilla, groin

-

Cavernous: upper trunk, extremities

-

Cystic signal characteristics with nonenhancing, fluid-filled, well-defined structures on MRI

-

Cystic structures on ultrasound

-

Marginal excision

-

High rate of local recurrence

make up the normal glomus body and are characterized best by their

clinical presentation as small painful nodules predominately found in a

subungual location.

-

Etiology unknown

-

Peak age: young adults predominate

-

Subungual lesions more common in women

|

|

Figure 11-34

Angiomatosis involves multiple tissue levels within a large segment of or an entire limb. This patient had undergone amputation for complications of angiomatosis of the lower extremity. Note the phleboliths within the soft tissues and involvement of the bone as well. |

|

|

Figure 11-35 Lymphangioma. Thin-walled vascular channels lined by flat endothelial cells and filled by proteinaceous material.

|

|

|

Figure 11-36 (A)

Glomus tumor. Nests of small, uniform, round cells with centrally located nucleus and amphophilic or slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm surrounded by capillary blood vessels. (B) Glomus tumor showing strong immunoreactivity with smooth muscle actin stain. |

-

Three components in varying amounts

-

Glomus cells

-

Small, uniformly round cells

-

Centrally placed round nuclei

-

Prominent cell membranes define cytoplasm.

-

-

Vascular structures

-

Smooth muscle cells

-

-

Familial cases: autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance

-

Subungual glomus tumors associated with NF-I

-

Typical glomus tumors have three histologic variants:

-

Glomangiomatosis: extremely rare clinical variant similar to angiomatosis but characterized by glomus histology

-

Symplastic glomus tumors: rare histologic variant with atypia but benign behavior

-

Malignant glomus tumors: 1% of glomus tumors

-

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

-

Subungual region (hand, wrist, foot) predominates.

-

Superficial in vast majority

-

Small reddish-blue nodules

-

Associated with chronic pain in severe paroxysms

-

Exposure to cold or minor pressure often exacerbates pain.

-

Ultrasound may detect tumors as small as 3 mm.

-

MRI: bright on T2-weighted images, dark on T1-weighted images; enhancing

-

Complete excision is the only treatment.

-

Local recurrence in 5% to 50%

the soft parts, is an extraosseous, extrasynovial mature hyaline

cartilage tumor.

-

Etiology is unknown.

-

Peak age: middle-aged (may involve any age)

-

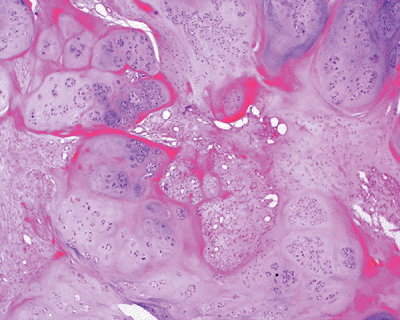

Histopathology: mature hyaline cartilage lobules, S100 positive (Fig. 11-37)

-

Genetics: 12q13-15 structural rearrangements involving HMGA2 gene locus

-

Chondroblastic chondroma: chondrocytic cells in lacunae predominate

-

Fibrochondroma: prominent fibrosis

-

Osteochondroma of soft tissue: prominent ossification centrally

-

Myxochondroma: prominent myxoid change

|

|

Figure 11-37 Soft tissue chondroma composed of well-defined lobules of mature cartilage embedded in a fibrous stroma.

|

-

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

-

Fingers (two thirds), hands, toes, feet predominate.

-

Painless small lumps rarely >3 cm

-

Plain films show variable mineralization.

-

MRI shows hyaline cartilage signal (lobulated, dark on T1-weighted images, bright on T2-weighted images).

-

Marginal excision

-

Recurrence unusual

radiographic appearance in showing very hypointense signal compared to

muscle on T1-weighted MRI. It may occur as a solitary soft tissue mass

or may be accompanied by fibrous dysplasia lesions, as in Mazabraud

syndrome.

-

Etiology is unknown.

-

Peak age: 40 to 70 years

-

Uniformly bland cellularity with small bland spindle cells

-

Bland extracellular myxoid background

-

Infiltrating borders

-

Point mutations in GNAS1 gene common both in Mazabraud syndrome and isolated myxomas

-

Cellular myxoma: histologic variant with increased cellularity and vascularity

-

Deep, painless soft tissue mass

-

Thigh, shoulder, buttocks, upper arm

-

Usually 5 to 10 cm

-

Mazabraud syndrome: myxomas and fibrous dysplasia (monostotic, polyostotic, or Albright syndrome)

|

|

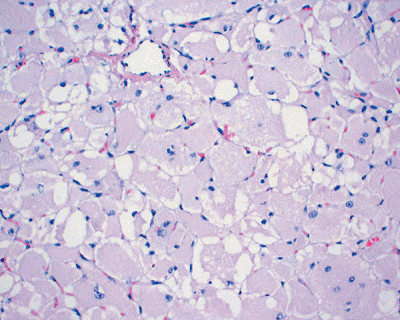

Figure 11-38 Intramuscular myxoma. Hypocellular neoplasm composed of very bland-looking spindle cells in an abundant myxoid background.

|

-

Homogenous, hypointense to muscle on T1-weighted images, hyperintense on T2-weighted images

-

Variable patterns of enhancement (peripheral and/or central) dependent on cellularity

-

Peritumoral edema and fat cap

-

This process may be highly suspected based on MRI, so biopsy may be unnecessary.

-

Also see Chapter 2.

-

Marginal excision

-

Recurrence unlikely

-

Etiology is unknown.

-

Peak age: range 9 to 83 years

-

Similar to cellular myxoma variant of intramuscular myxoma

-

Bland spindle cells

-

Myxoid background

-

-

Cystic-like ganglion spaces

-

Lacks the GNAS1 mutations seen in intramuscular myxomas

-

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

-

Frequently painful or tender soft tissue mass

-

Present for weeks to years

-

May be associated with meniscal tear

-

May be incidental finding during knee or hip arthroplasty

-

Similar to intramuscular myxoma

-

Distinguished by juxta-articular location

-

Marginal excision

-

Local recurrence in up to one third

|

|

Figure 11-39 This intramuscular myxoma within the quadriceps shows characteristically hypointense signal on T1-weighted sagittal (A) and axial (C) MRI sequences and hyperintense signal on T2-weighted coronal (B) and axial (D) sequences.

|

MT, Zagars GK, Pollack A, et al. Desmoid tumor: prognostic factors and

outcome after surgery, radiation therapy, or combined surgery and

radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol 1999;17(1):158–167.

DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, et al. A series of 397 peripheral neural

sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health

Sciences Center. J Neurosurg 2005;102(2):246–255.