AMPUTATIONS OF THE LOWER EXTREMITY

VII – NEOPLASTIC, INFECTIOUS, NEUROLOGIC AND OTHER SKELETAL DISORDERS

> Amputations > CHAPTER 120 – AMPUTATIONS OF THE LOWER EXTREMITY

the United States annually has remained fairly steadily between 30,000

and 40,000 over the last 15 years (3). Most of

the amputees are older people with ischemic disease of the lower

extremities or diabetes of long standing. Amputations are a major

social and economic burden to society. Moreover, the amputation of one

lower extremity in the elderly all too frequently is followed by the

amputation of the contralateral limb; this occurs in 15% to 28% of

cases within 3 years. Only 50% of elderly amputees survive the first 3

years following an amputation. In spite of the advances in medicine

these statistics have not improved significantly for the dysvascular

amputee (9,12,14,59,63).

failure of treatment. Frequently, it is the treatment of choice for a

devastating injury to the lower extremity where reconstruction may be a

long and costly undertaking that leads to the preservation of a

functionally unsatisfactory extremity (33,34 and 35,65,72). It is important that amputation be done well and with adequate preoperative planning (4),

so that the outcome results in a residual limb that can wear a

prosthesis comfortably. With a prosthesis that fits well, the patient

is most likely to become an active member of society and independent in

his life-style.

includes the primary care physicians, the surgeons, a physical therapist, a prosthetist, and a social worker (53).

The patient must be involved and committed to a successful outcome. In

the case of patients with vascular disease, other organ systems are

usually involved. An internist who is familiar with the patient’s

condition must be involved and should counsel the patient (5,13,52).

requiring amputation and usually occurs in the geriatric patient. Since

preservation of a functioning knee greatly improves the chances of

rehabilitation of the amputee, consider reconstruction of occluded

major proximal arteries, which may save the limb or at least allow

amputation below the knee (1,25,58,67,71,72).

These patients have the added problems of peripheral neuropathy.

Therefore, they are subject to trophic ulcers and Charcot

osteoarthropathy. Indeed, frequently the amputation in patients with

diabetes is performed because of osteomyelitis caused by a trophic

ulcer that has exposed bones of the foot. Instability of the foot or

ankle because of the osteoarthropathy may also require amputation (8,44,63).

usually because of an irreparable acute vascular injury. Treatment of

lacerations of the popliteal artery has improved: During World War II,

amputation occurred in 72% of these cases (15), whereas 68% were successfully treated with vascular reconstruction in both the Korean War (39) and the Vietnam War. This rate of success has been reflected in the civilian experience (13,15,39,66).

with an open fracture, a vascular injury requiring repair, or

transection of the posterior tibial nerve is challenging, requiring a

long and expensive course of treatment with numerous surgical

procedures. Even if the limb can be saved, it is often painful and not

as useful as a prosthesis. This, together with a protracted course of

treatment, places an undue psychological burden on the patient (38,40,63). See Chapter 12 and Chapter 24 for a thorough discussion of these issues.

tumors of the extremities, combined with adjuvant therapy, has reduced

the incidence of amputations for primary malignancies of the lower

extremities (19,20,41,50,57,70,75). This is discussed in detail in Chapter 128 and Chapter 129.

wellvascularized subcutaneous tissue and skin that will withstand

pressure in weight-bearing areas, and friction in areas covered by the

prosthesis. Stumps that allow end bearing are particularly desirable.

Usually, end-bearing stumps retain a part of the sole pad or have a

bony surface of sufficient size that it can bear the body weight for

varying periods of time. These conditions are common in partial foot

amputations.

or knee disarticulation. Disarticulation is particularly desirable in

growing children and in the elderly. In children, overgrowth, which is

seen often in diaphyseal amputations, is avoided by retaining the

epiphysis (26,45). In the elderly, an end-bearing stump decreases problems with fitting and improves the chances for rehabilitation (37,64). The creation of a tibiofibular synostosis as described by Ertl (24) can create end-bearing conditions somewhat comparable to those of the disarticulation.

important for the healing of the amputation wound, several methods have

been developed to predict at which level of the lower extremity the

circulation in the skin is adequate for primary wound healing. One of

these is the xenon-133 (133Xe) clearance. After the ambient

conditions have been regulated, radionuclide is injected intradermally.

A gamma camera monitors the 133Xe activity for 10 minutes. The faster the 133Xe is cleared from the site of injection, the better the perfusion of the skin (34,46).

major amputations, the most accurate is probably the transcutaneous

measurement of oxygen tension. The oxygen sensor is calibrated for

temperature and atmospheric pressure and applied to the skin. The skin

is heated to 45°C. The sensor stabilizes after approximately 20

minutes. The minimal desirable tension varies between 30 and 50 mm of

mercury (7,47).

the affected extremity is entirely reliable for predicting success in

healing of the amputation wound. Other conditions, such as nutrition,

state of health, age, collateral circulation, and infection, play a

role in the success or failure of the amputation.

|

|

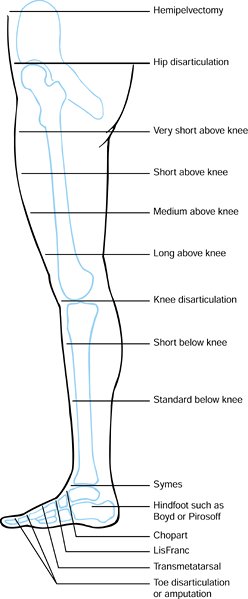

Figure 120.1. Levels of lower extremity amputation.

|

the amputation wound. It is therefore important that it be handled with

care. The use of skin hooks in particular is desirable in patients with

dysvascular extremities.

not entirely contraindicated in the lower extremity. As long as a

split-thickness graft is over soft tissue and not adherent to bone or

thick scars, it is likely to withstand the prosthetic wear. Pedicle

grafts do even better as long as they are not in the immediate

weight-bearing area of the residual extremity (74). Skin grafts are more successful in children than in adults.

soft-tissue mantle for the residual extremity. This can be achieved

best through myodesis (suturing the transected muscle end to drill

holes in the bone) or myoplasty (suturing the cut ends of the

antagonistic muscle groups and their fascias together). Under normal

circumstances, the cut muscle ends have the greatest amount of

capillary bleeding. Therefore, the suction drain should be in this

layer of the amputation stump.

stumps, such as in partial foot amputations or disarticulations, bony

prominence under this skin should be removed. Consider the possibility

of an osteoplastic treatment of the bones, such as a tibiofibular

synostosis (24).

without exception to the formation of neuromas. In the vast majority,

these neuromas are painless. However, where the cut end of the nerve is

within the weight-bearing area of the residual extremity, the neuroma

can become painful. Therefore, during the amputation each nerve should

be identified, dissected free to a level well above the amputation, and

sharply transected. Where a concomitant vessel is expected, ligate the

nerve before cutting it under minimal tension.

ligate them before transection. It is advisable not to catch

neighboring veins and arteries in the same ligature, since this might

lead to the development of aneurysms.

overwhelming infections, particularly infection by gas-producing

bacteria, an open amputation (43,66,69)

may be indicated. The aim of this surgery is to eradicate the diseased

area without creating a harbor for renewed infection. Although a

straight guillotine transverse amputation is the simplest, we prefer to

develop flaps as the secondary revision, and closure is then usually

easier.

-

Prepare the skin flaps that are necessary

for the secondary closure of the amputation wound. You may want to make

the initial skin flaps somewhat longer than usual, as some retraction

will occur. -

Transect the soft tissues and bone in the usual fashion.

-

Carry out hemostasis and transection of the nerves as described previously.

-

To prevent the skin flaps from

retracting, invert and suture the free skin edges to the subcutaneous

fascia at the base of the flaps with nonabsorbable sutures to be

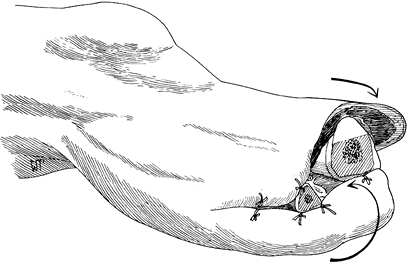

unrolled at the time of secondary closure (Figure 120.2.). Only in patients with excellent circulation should you use skin traction to prevent skin retraction. Figure 120.2. Open amputation with preservation of flap length using inversion technique. See text for details. (From Bohne WHO.Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:36, Fig. 8-9, with permission.)

Figure 120.2. Open amputation with preservation of flap length using inversion technique. See text for details. (From Bohne WHO.Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:36, Fig. 8-9, with permission.)

-

Select the level of amputation depending

on the pathology being treated. Preservation of some part of the toe

helps prevent migration of the other toes into the void created by the

missing toe. -

Develop equivalent-length dorsal and

plantar full-thickness, fishmouth-type skin flaps, favoring the tougher

plantar skin for the end of the stump. -

Transect the extensor tendon and let it retract.

-

Work from dorsal to plantar. Disarticulate the joint or transect the bone at the appropriate level and smooth the end.

-

Identify the neurovascular bundles. Cut the digital nerves back sharply and ligate the arteries and veins.

-

Then transect the flexor tendons and let them retract.

-

Close the skin flaps with interrupted

absorbable sutures in the subcutaneous fat, and interrupted 5-0 nylon

sutures in the skin. Do not resect “dog-ears,” as they will retract and

assume a smooth contour.

perforating ulcer under one of the metatarsal heads that has not healed

in spite of prolonged care, and when osteomyelitis involves the

metatarsal.

-

Make a racket-type incision

circumferentially around the toe, with a single limb over the dorsum of

the involved metatarsal, and including the area of the ulcer on the

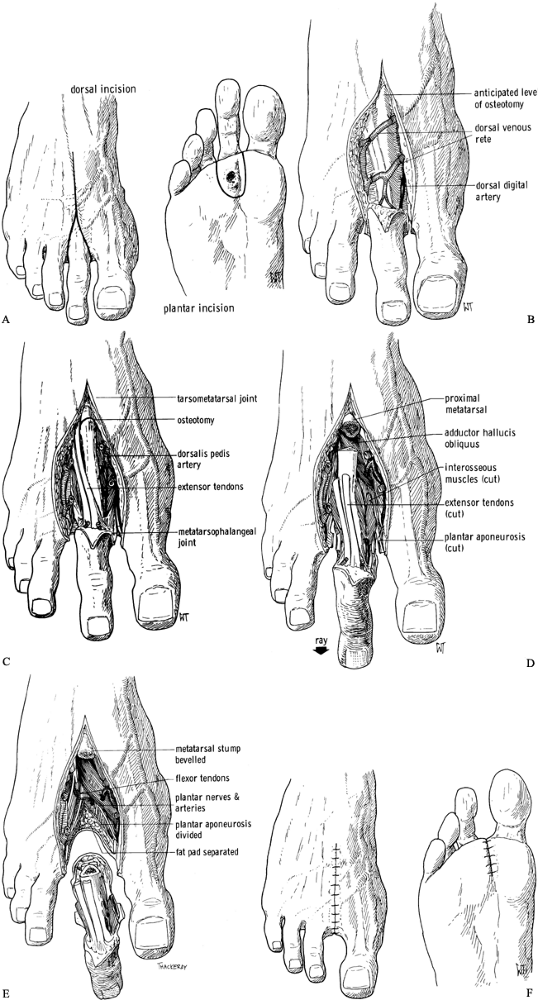

plantar surface (Figure 120.3.A).![]() Figure 120.3. Amputation of the second ray of the foot. See text for details. A: Skin incision. B: Dorsal soft-tissue dissection to expose the metatarsal. C: Osteotomy at the base of the metatarsal. D: Release of other soft tissues. E: The metatarsal and toe are now free. F: Skin closure. (From Bohne WHO. Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:40–42, Fig. 10-1, Fig. 10-2, Fig. 10-3, Fig. 10-4,Fig. 10-5 and Fig. 10-6 with permission.)

Figure 120.3. Amputation of the second ray of the foot. See text for details. A: Skin incision. B: Dorsal soft-tissue dissection to expose the metatarsal. C: Osteotomy at the base of the metatarsal. D: Release of other soft tissues. E: The metatarsal and toe are now free. F: Skin closure. (From Bohne WHO. Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:40–42, Fig. 10-1, Fig. 10-2, Fig. 10-3, Fig. 10-4,Fig. 10-5 and Fig. 10-6 with permission.) -

Dissect open the skin on the dorsum of

the foot like a double door. Follow the intermetatarsal space without

incising the periosteum except at the very base of the metatarsal (Figure 120.3.B).

Identify and transect the digital nerves to the amputated toe. Preserve

the branches to the adjacent toes. Identify and ligate the digital

arteries and veins. -

Transect the base of the metatarsal (Figure 120.3.C),

lift up the distal end, and continue the dissection on the plantar

surface, including the part of the plantar fascia belonging to the

diseased ray. You can then lift the ulcer, the toe, and the surrounding

skin out of the wound. Leave the surrounding intrinsic muscles attached

to the metatarsal (Figure 120.3.D, Figure 120.3.E). -

Obtain hemostasis. Either leave the wound

open until secondary closure, or close the intermetatarsal space with

interrupted absorbable sutures and the skin with interrupted 5-0 nylon

sutures (Figure 120.3.F) (15).

leads to a transfer lesion on the second metatarsal. Therefore, in

these cases a transmetatarsal amputation may be the better choice.

toes and the metatarsal heads and necks. It requires a long plantar

flap to cover the anterior part of the amputation wound. In general, it

creates an excellent weight-bearing foot remnant. However, you must

consider that the fifth metatarsal is more horizontal than the first

metatarsal, so the shoe insert that is required after the

rehabilitation has to provide sufficient medial support to distribute

weight bearing evenly.

-

This procedure requires transection of

the dorsal skin slightly distal to the level of the bony amputation.

The plantar flap must be long enough to cover the ensuing amputation

wound. It must avoid any ulcerations that may be present on the plantar

surface of the forefoot (Figure 120.4.A).

Expose the metatarsals dorsally. Transect the extensor tendons, ligate

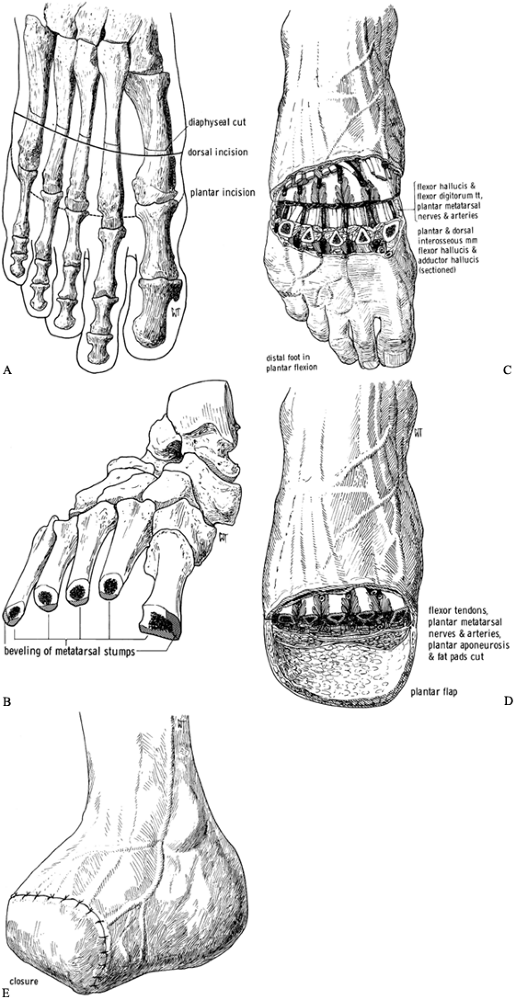

the dorsal veins, and cut back sharply the cutaneous nerves (Figure 120.4.B). Figure 120.4. Transmetatarsal amputation. See text for details. A: Dorsal and plantar skin incisions relative to level of transection of the metatarsals. B:

Figure 120.4. Transmetatarsal amputation. See text for details. A: Dorsal and plantar skin incisions relative to level of transection of the metatarsals. B:

Transection of the metatarsals produces a cascade in which the fifth

metatarsal remnant is slightly shorter than the first. Bevel the

prominent plantar edges of the metatarsal remnants as well as the

lateral aspect of the fifth and medial aspect of the first. C: Plantar-flex the forefoot after transection of the metatarsals to gain access to the plantar structures. D: Completed amputation. E: Skin closure. (From Bohne WHO. Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:44–47, Fig. 11-2, Fig. 11-5, Fig. 11-6, Fig. 11-7 and Fig. 11-8, with permission.) -

Carry out bony transection from the

dorsum of the foot. There should be a slight cascade, with the fifth

metatarsal remnant being minimally shorter than the first one. -

Transect the metatarsals with a small

oscillating saw. Deliver the distal ends of the metatarsal into the

wound and expose the flexor tendons and plantar neurovascular bundles (Figure 120.4.C). Divide and ligate these in an orderly fashion with the techniques described previously, preserving the plantar flap (Figure 120.4.D). -

Where possible, tack down the plantar pad

to the periosteum on the dorsum of the metatarsal remnants and

approximate the edges of the skin of the plantar and dorsal aspects (Figure 120.4.E).

tarsometatarsal joints, whereas the Chopart amputation is a

disarticulation through the talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints.

Both amputations sacrifice the insertions of the muscles that aid in

the extension of the ankle joint; therefore, the anterior tibial

tendon, the toe extensors, and the peroneal tendons must be reinserted

into the tarsal bones. Even so, dorsiflexion of the ankle joints often

is inadequate, requiring a transcutaneous Achilles tenotomy. These

levels of amputations are less desirable than a transmetatarsal

amputation, as the stump has a tendency to develop an equinus posture

over time. Increased weight-bearing pressures over the plantar aspect

of the end of the

stump

may lead to pain and/or ulceration. On the other hand, when one of

these amputations is successful, its advantages are that it is end

bearing, does not sacrifice leg length, and requires only a filler in a

regular shoe in most cases.

-

Transect the dorsal skin at the level of

the disarticulation. The plantar skin flap must be long enough to cover

the anterior aspect of the remaining limb. -

Transect the extensor tendons somewhat distal to the skin incision to allow their insertion into the tarsal bones.

-

Transect the ligaments and joint capsules

of the tarsometatarsal joints, in the case of the LisFranc amputation,

and of the talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints, in the case of the

Chopart amputation. Sharply plantar-flex the forefoot. The capsule and

plantar ligaments can be transected as well as the flexor tendons. Take

care not to injure the medial or lateral plantar artery and nerves. -

Dissect the part of the foot to be

amputated off the plantar flap, which should not be debrided to allow

full-thickness coverage of the anterior part of the stump. -

Leave the cartilage of the tarsal bones

and the remaining limb intact. This cartilage presents an effective

barrier against infections of the bone, and it decreases blood loss

from bone bleeding. Nevertheless, introduce a drain into the amputation

wound. -

Close the plantar flap to the dorsal

incision, securing the deep fascia to the periosteum and deep fascia of

the stump with absorbable sutures. Close the skin with interrupted 4-0

or 5-0 nylon or similar sutures.

amputation of the foot that allows the possibility of fitting with a

shoe and shoe filler; however, frequently the patient prefers a formal

prosthesis because the shoe is unstable (10).

surface of the heel by creating an arthrodesis between the distal tibia

and the tuber of the calcaneus (45). Compared

to a Syme’s amputation, it provides more length and better preserves

the weight-bearing function of the heel pad. Its increased complexity

and morbidity have made it less used now than the Syme’s amputation.

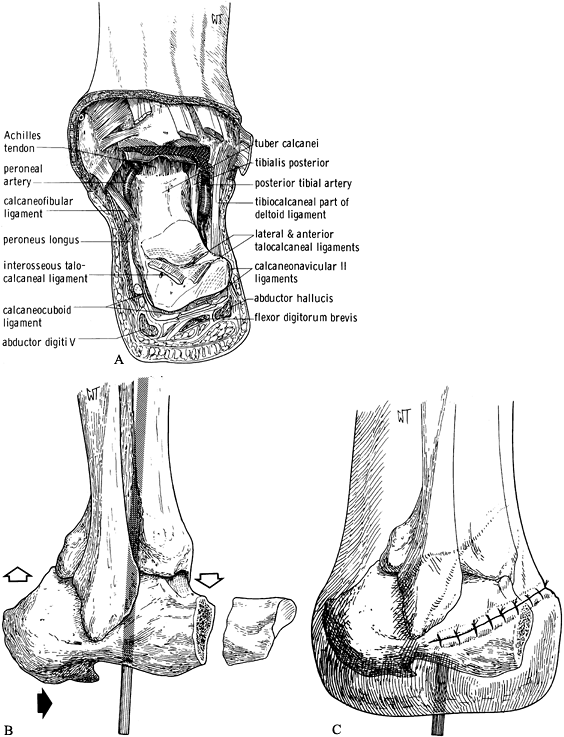

The Pirogoff amputation removes the anterior two thirds of the

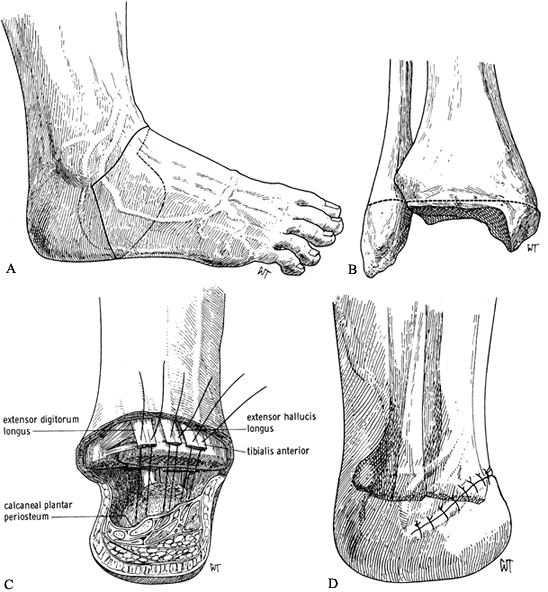

calcaneus (Figure 120.5.) but has no advantage over the Boyd amputation, which is described later.

|

|

Figure 120.5. Pirogoff amputation with fixation of the tuberosity of the calcaneus to the tibia.(From Bohne WHO. Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:53, Fig. 12-7, with permission.)

|

-

Make the dorsal skin incision from the medial to the lateral malleolus across the anterior aspect of the ankle

P.3157

joint. Connect this to a plantar incision through the plantar fat pad

at the midtarsal joint region. Take care not to injure the tibial

neurovascular bundle. Plantar-flex the foot. Place a bone hook in the

posterior talus and pull it forward. Excise the talus. The plantar pad

remains attached to the undersurface of the calcaneus. Remove the

portion of the foot to be amputated (Figure 120.6.A). Figure 120.6. Boyd amputation. See text for details. A: Anterior–dorsal skin incision and exposure with excision of the talus. B:

Figure 120.6. Boyd amputation. See text for details. A: Anterior–dorsal skin incision and exposure with excision of the talus. B:

Excise the anterior process of the calcaneus and remove cartilage from

the articular facets. Fit the calcaneus into the ankle mortise,

shifting it anteriorly. Secure it with a Steinmann pin. C: Completed amputation with skin closure. (From Bohne WHO. Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:56–57, Fig. 12-11, Fig. 12-13, Fig. 12-14, with permission.) -

Remove the anterior process of the

calcaneus. Fashion the ankle mortise in such a way that the

decorticated superior part of the tuber calcanei can be fitted into the

ankle mortise with good bone apposition. Slide the calcaneus somewhat

anteriorly. -

Fix the tuber calcanei into the ankle mortise with either a Steinmann pin or a partially threaded cancellous screw (Figure 120.6.B).

-

Pull the plantar skin flap over the

anterior aspect of the calcaneal remanent, and close it in layers at

the anterior aspect of the ankle joint (Fig. 120.6C). Postoperative casting may be necessary to provide secure arthrodesis between the ankle mortise and the calcaneal remanent.

in many circumstances allows ambulation without a prosthesis over short

distances. It is an excellent amputation for children, in whom it

preserves the physes at the distal end of the tibia and fibula (26).

assuming that the heel flap has been spared from the trauma. In the

past, it has had a high failure rate in ischemic limbs because of

failure of wound healing. Today, the success of amputation at this

level has increased because local tissue perfusion is preoperatively

determined with Doppler ultrasound measurement of blood pressures, with

radioactive 133Xe clearance tests, and with transcutaneous measurement of oxygenation.

two-stage amputation, where the wound is left open initially and the

viability of the heel flap is established prior to definitive wound

closure, has also increased success rates. The two most common problems

with the Syme’s amputation are skin slough due to trimming of the

dog-ears of the skin flaps, which interferes with the blood supply to

the heel pad, or late migration of the heel pad due to instability. The

risk of both of these problems can be minimized by careful attention to

surgical technique.

that a below-knee prosthesis must be worn, which is rather bulky around

the ankle because of the need to accommodate the flair of the distal

tibial metaphysis. The prothesis consists of a molded plastic socket

with a removable medial window through which the stump is inserted.

Usually a solid-ankle, cushion-heel (SACH) foot is attached. For this

reason, the Syme’s amputation has not often been recommended for women,

but active athletic women probably would prefer this level of

amputation because it is much more functional for sports activities

than a standard below-knee amputation.

-

Make a dorsal skin incision from the

medial to the lateral malleolus over the anterior aspect of the ankle

joint. Continue the plantar incision around the anterior process of the

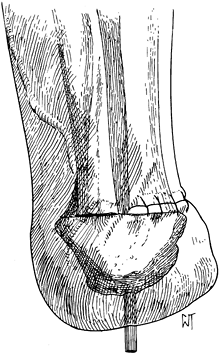

calcaneus (Figure 120.7.A). Transect the extensor tendons and cut back sharply the cutaneous nerves. Ligate the dorsalis pedis artery and vein.![]() Figure 120.7. Syme’s amputation. A: Skin incisions. B: Level of bone transection in adults. C: Begin closure of the wound by attaching the extensor tendons to the calcaneal periosteum to help stabilize the heel pad. D: Skin closure. (From Bohne WHO. Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:58–62, Fig. 12-15, Fig. 12-21, Fig. 12-22 and Fig. 12-23, with permission.)

Figure 120.7. Syme’s amputation. A: Skin incisions. B: Level of bone transection in adults. C: Begin closure of the wound by attaching the extensor tendons to the calcaneal periosteum to help stabilize the heel pad. D: Skin closure. (From Bohne WHO. Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:58–62, Fig. 12-15, Fig. 12-21, Fig. 12-22 and Fig. 12-23, with permission.) -

Disarticulate the talus from the ankle

mortise by transecting the medial and lateral collateral ligaments.

Take care not to injure the tibial neurovascular bundle. Strip the

calcaneus subperiosteally and remove it from the heel pad. This

dissection can be difficult and is aided by placing a bone hook into

the posterior aspect of the talus and pulling it and the calcaneus

anteriorly. Then use a sharp scalpel to meticulously dissect the

calcaneus free from the heel pad, at a subperiosteal level. -

When the calcaneus is free, transect the

plantar tendons and neurovascular bundles, taking care to protect the

vascular supply and sensory nerves to the heel pad. -

In a standard Syme’s amputation in adults, remove the malleoli at the level shown in Figure 120.7.B. In children and for first-stage amputations in diabetics, leave the malleoli intact.

-

Start closure of the wound by suturing

the anterior tibial tendon as well as the extensor digitorum longus

tendon into the anterior part of the heel pad. This prevents, at least

to some extent, posterior migration of the heel pad (Figure 120.7.C). Complete a layered closure as described previously. -

Since the removal of the calcaneus from

the heel pad creates a large empty space, insert a suction drain to

prevent the formation of a large hematoma. There is a mismatch between

the thin skin at the anterior aspect of the ankle joint and the thick

plantar skin. However, the ridge that is created by the skin closure

flattens out eventually. Large dog-ears are usually created by this

closure. Do not trim these. They eventually flatten out.

good soft-tissue coverage of the bony stump end is possible. The

minimal length of the bony stump for good function is about 12 cm, as

measured from the medial tibial plateau distally, and the maximum

length is 17 cm, depending on the height of the patient. Longer stumps

require less energy consumption during gait and can be fitted with

sockets without special suspension. Very short stumps often

require knee hinges and a thigh lacer and are much less functional.

the second provides equal skin flaps posteriorly nand anteriorly; the

third and most common approach provides a long posterior flap. The

latter is most desirable in dysvascular patients and leaves the patient

with a scar on the anterior aspect of the residual limb. However, other

methods of skin closure have been successful (Figure 120.8.) (32,42,68).

|

|

Figure 120.8. Suture line in various types of below-knee amputations. A: In the nonischemic limb. B: Amputation of the ischemic limb in the coronal plane. C: Amputation of the ischemic limb in the sagittal plane. (From Bohne WHO. Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:69, Fig. 13-8, with permission.)

|

-

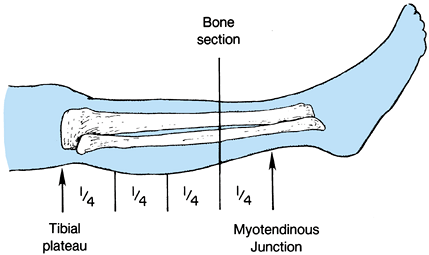

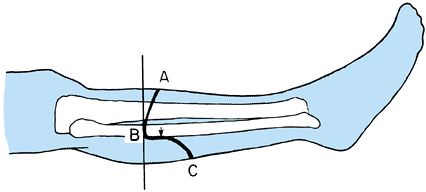

Determine the level of transection of the tibia by direct measurement, or using the method depicted in Figure 120.9.

![]() Figure 120.9.

Figure 120.9.

Use a sterile marking pen to divide the leg into four equal quadrants

from the tibial plateau to the myotendinous junction of the

gastrocsoleus muscle. In most cases, transect the bone at the distal

portion of the third quarter. -

In the long posterior flap method, make

the skin incision at the anterior aspect of the tibia, 1.3 cm distal to

the level of the bone transection. The posterior flap must be long

enough to provide soft-tissue coverage without undue tension (Figure 120.10.). Extend the incision down to the deep fascia and periosteum of the tibia veering medially and laterally to point B on Figure 120.10.,

which is two thirds of the anteroposterior (AP) diameter of the calf.

Then curve the incision directly distal for a distance of 1.3 cm before

sloping posteriorly to create the posterior flap. The length of the

posterior flap must be more than two thirds of the AP diameter of the

calf at the level of the bone transection. Figure 120.10. Skin incision for a below-knee amputation as described by Mooney.

Figure 120.10. Skin incision for a below-knee amputation as described by Mooney. -

Raise the periosteum of the tibia and

transect it with an oscillating saw. Bevel the anterior aspect of the

tibia. Transect the fibula with an oscillating saw 1–2 cm proximal to

the level of the tibial transection. -

Working from anterior to posterior, transect the muscles

P.3161

and neurovascular bundles. Pulling the distal tibia anteriorly places

the soft tissues under tension and facilitates dissection. Transect the

muscles of the anterior, lateral, and deep posterior compartments just

distal to the end of the tibia, so that when they retract they are even

with the end of the tibia. Identify each neurovascular bundle. Cut the

nerves back sharply and doubly ligate the arteries and veins

independently. -

Bevel the posterior flap to produce

adequate coverage for the end of the amputation stump. At the level of

the skin, it should consist only of fascia. -

Carry out a myoplastic closure, suturing

the fascia of the posterior flap to the anterior compartment and the

periosteum of the tibia. Lead a drain out through the skin laterally.

Particularly in the dysvascular patient, avoid any tension in the skin

closure (Figure 120.11.).![]() Figure 120.11.

Figure 120.11.

Below-knee amputation. Myoplastic closure with approximation of the

fascia of the posterior flap to the fascia of the anterior compartment

and periosteum of the tibia, and subsequent closure of the subcutaneous

tissues and skin over a drain placed at the level of the bone. (From

Bohne WHO. Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:68, Fig. 13-7, with permission.)

The main advantage is the creation of an endbearing stump and

preservation of the distal femoral physes, which is particularly

desirable in children. Another advantage is the maintenance of a long

active lever arm for control of the prosthesis, with excellent muscle

attachments. The bulbous distal stump enhances suspension of the

prosthesis. In elderly dysvascular patients, the longer stump helps

prevent hip flexion contractures and it provides better balance for

wheelchair activities. Knee disarticulation is most useful in young

athletic amputees in whom a below-knee amputation is not feasible.

Several modifications have been introduced by Mazet and Hennessy (60) and Burgess (6), and they are incorporated here.

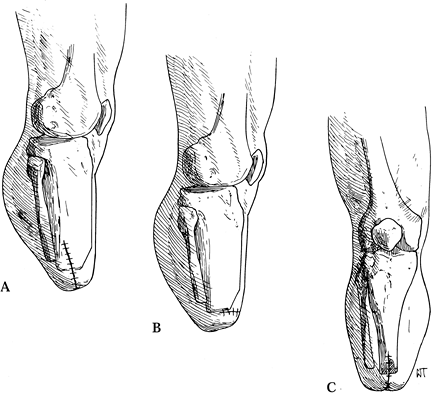

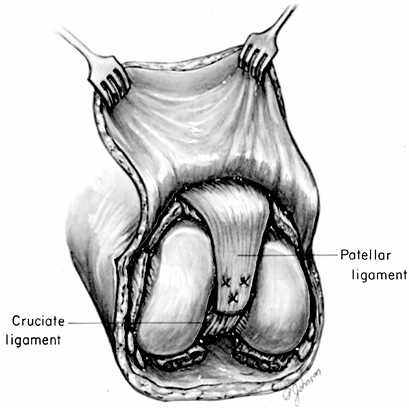

-

Equal anteroposterior or mediolateral skin flaps using a fishmouth type of incision are acceptable.

-

Start the anterior skin incision

approximately 2 cm below the tibial tubercle. The posterior incision is

usually at the level of the distal popliteal flexion crease. -

Raise a skin and subcutaneous fat flap and transect the patellar ligament as far distally as possible.

-

Open the anterior capsule and transect

the collateral ligaments. Transect the cruciate ligaments at their

insertion on the tibial plateau. -

Open the posterior capsule and doubly

ligate the popliteal vessels distally to the level of the superior

geniculate artery. Sharply transect the nerves well proximally to the

skin incision. -

Transect the tendons of the knee flexors as far distally as possible.

-

Using an oscillating saw, remove the femoral condyles 1.5 cm proximal to the knee joint.

-

Shell the patella out of the patellar

tendon. Suture the patellar tendon and the flexor tendons of the knee

to the cruciate ligaments (Fig. 120.12). Figure 120.12.

Figure 120.12.

Knee disarticulation. Suturing of the patellar ligament to the cruciate

ligaments. Suturing of the hamstring tendons to the cruciate ligaments

and resection of the distal femoral condyles as described by Burgess (6) is not illustrated.

diaphyseal amputation through the femur becomes necessary. The

soft-tissue coverage of the above-knee stump is excellent and usually

provides good arterial perfusion to allow primary healing of the

amputation. It is the most commonly used amputation for vascular

disease because it heals reliably. The optional level for prosthetic

fitting is at the junction of the distal and middle thirds.

gluteal crease have been fitted successfully with prostheses, a longer

amputation stump makes prosthetic fitting, as well as rehabilitation,

easier and more successful. Equal anterior and posterior soft-tissue

flaps are used most commonly, but atypical soft-tissue coverage is well

tolerated in above-knee amputations.

-

Make a fishmouth skin incision to create equal anterior and posterior flaps (Figure 120.13.A).

![]() Figure 120.13. Above-knee transdiaphyseal amputation. A: Skin incisions relative to the level of transection of the femur. B: Myodesis closure of the stump over a drain. (From Bohne WHO. Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:87–89, Fig. 14-4, 14-7, with permission.)

Figure 120.13. Above-knee transdiaphyseal amputation. A: Skin incisions relative to the level of transection of the femur. B: Myodesis closure of the stump over a drain. (From Bohne WHO. Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:87–89, Fig. 14-4, 14-7, with permission.) -

After the skin incision, transect the

quadriceps musculature anteriorly; this will leave the muscle even with

the level of bone transection. -

Next, either cut the femur (as this

permits the transection of tissues from anterior to posterior) or

complete the soft-tissue work prior to cutting the bone. Cut the

adductors and hamstrings so that they also lie even with the cut bone. -

If you have not done so already, transect the bone and round off the sharp edges.

-

Obtain hemostasis and isolate and doubly

ligate the large vessels with at least one suture ligature. Place a

ligature on the sciatic nerve well above the level of amputation, prior

to sharply transecting the nerve. -

Fashion the muscle flaps and do a myoplasty by approximating the anterior to the posterior myofascial flap (Figure 120.13.B).

In younger active patients, place two drill holes in the bony stump end

for each compartment, and do a myodesis by pulling the muscles out to

length and securing them to the bone end with sutures. This improves

the power and control over the stump and keeps the bone centralized in

the stump. -

Place a drain and close the subcutaneous flap and skin loosely with interrupted sutures or staples.

malignancies. Prosthetic fitting is quite possible, although

rehabilitation is most successful in younger and more vigorous

individuals, since the prosthetic gait requires considerable

expenditure of energy. Very short above-knee amputations (Figure 120.1.) are fitted with a hip disarticulation prosthesis (Chapter 122), as is the short stump that cannot control an above-knee prosthesis even with a hip hinge and waist belt.

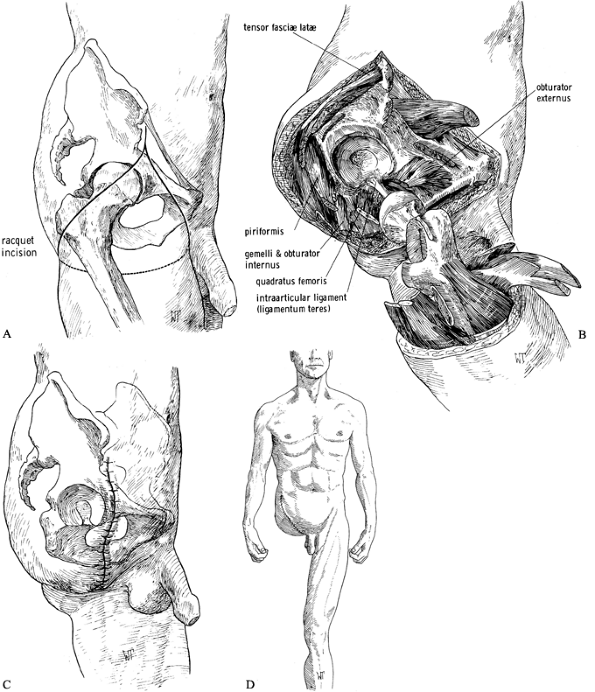

-

Place the patient in the lateral

decubitus position with the operated side uppermost, and prepare and

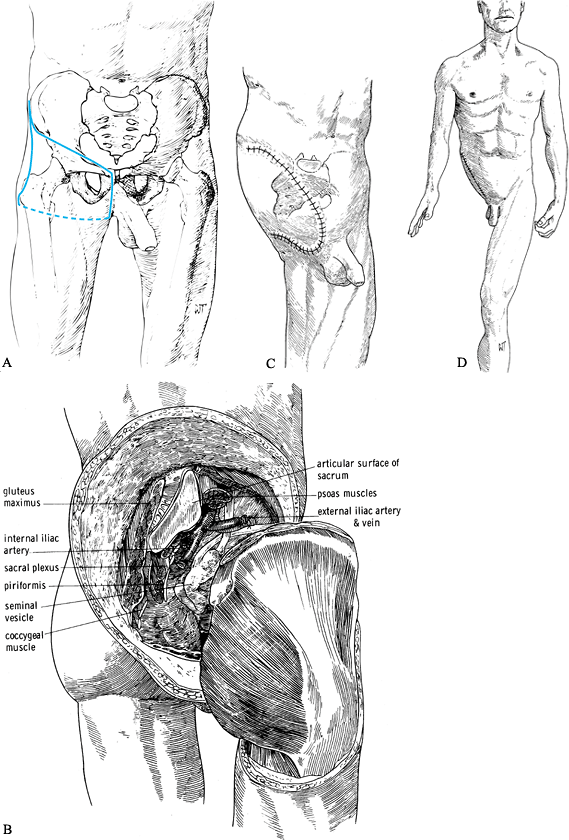

drape the limb free, including the hip and groin. -

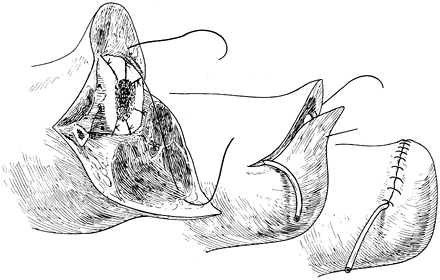

Make a racket-type incision down to the

deep fascia, that starts at the anterior superior iliac spine, follows

the inguinal ligament to a point 5 cm below the pubic tubercle, and

curves around the medial and posterolateral aspects of the thigh

approximately 5 cm below the ischial tuberosity. The incision then

extends anteriorly to the greater trochanter and joins the beginning of

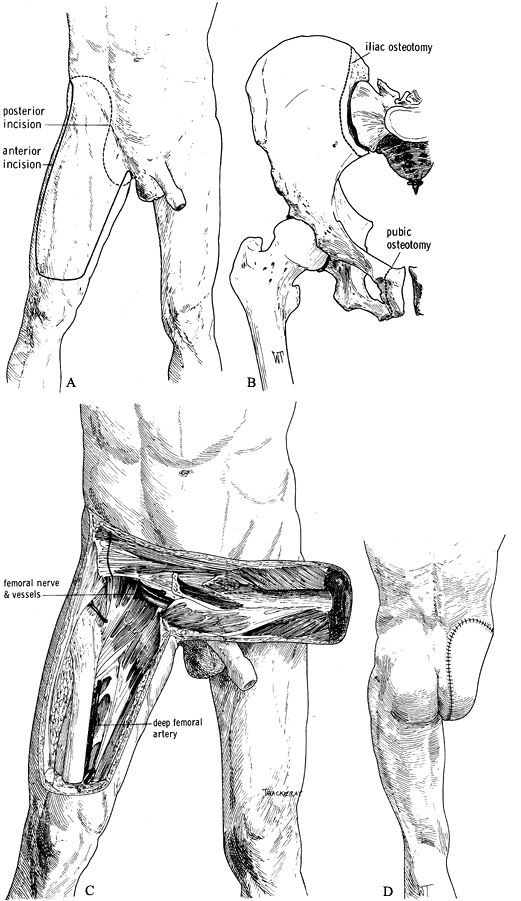

the incision at the anterior iliac spine (Figure 120.14.A). Figure 120.14. Disarticulation of the hip. See text for details. A: Racket-type skin incision. B: The hip disarticulation is completed except for cutting the ligamentum teres. C: Skin closure. D: Frontal view of a patient after hip disarticulation. (From Bohne WHO. Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:106–111, Fig. 14-28, Fig. 14-31, Fig. 14-34, Fig. 14-35, with permission.)

Figure 120.14. Disarticulation of the hip. See text for details. A: Racket-type skin incision. B: The hip disarticulation is completed except for cutting the ligamentum teres. C: Skin closure. D: Frontal view of a patient after hip disarticulation. (From Bohne WHO. Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:106–111, Fig. 14-28, Fig. 14-31, Fig. 14-34, Fig. 14-35, with permission.) -

Anteriorly expose the femoral artery and

vein. Isolate them and doubly ligate them. Dissect the femoral nerve

free, ligate it, and transect it sharply farther proximally. -

Transect the muscles originating from the

iliac spine and retract them distally. Transect the pectineus muscle a

finger’s breadth laterally to the pubic ramus. Externally rotate the

hip and transect the psoas tendon. Next, detach the muscles from the

pubic bone and the adductor magnus as it originates from the ischium. -

Between pectineus and the hip external

rotators, dissect the obturator artery free and ligate it. Transect the

obturator externus distal to the obturator foramen, because

P.3163

inadvertent

transection of the obturator artery leads to retraction of the vessel

into the inner pelvis, where it is difficult to recover for ligation. -

Then internally rotate the hip and transect the gluteus medius and minimus muscles at the greater trochanter.

-

Divide the fascia lata either above or below the insertion of the tensor fasciae latae muscle.

-

Next divide the lower fibers of the

gluteus maximus and detach its tendon from its insertion into the linea

aspera. Retract the gluteus maximus and identify and ligate the sciatic

nerve and divide it as far proximally as possible, but outside the

sciatic foramen. Then transect the external rotators of the hip and

divide the origins of the hamstring muscles at the ischial tuberosity. -

Complete the amputation by transecting the joint capsule and intra-articular ligament as close to the acetabulum as possible (Figure 120.14.B). Ensure good hemostasis.

-

Place large suction drains, one deep in the wound and one above the fascia.

-

Begin the closure of the wound by

suturing the tendons of the glutei medius and minimus to the transverse

acetabular ligament. Suture the gluteus maximus forward to the origin

of the pectineus, obturator externus, iliopsoas, and adductor muscles.

Close the skin without tension.

hindquarter amputation, is the eradication of malignant tumors of the

soft tissues or bone of the hip or pelvis. Occasionally, overwhelming

infections such as gas gangrene or the consequences of trauma may

require this operation. Prosthetic fitting is difficult and relies on

weight bearing on the uninvolved side. Energy expenditure for

prosthetic gait is considerable. Depending on the location of the

tumor, an anterior-flap or a posterior-flap technique can be used. In

an attempt to improve the prosthetic fitting, consider a conservative

hemipelvectomy, which retains the ileum and its attachment to the

sacroiliac joint. Another possibility is the excision of the

hemipelvis, including the hip joint, while maintaining the lower

extremity

without its attachment to the pelvic girdle. Expect considerable blood loss during the operation.

and sometimes anteriography is usually necessary to plan for safe

margins for tumor resection and to determine what type of

hemipelvectomy is appropriate.

-

Insert a ureteral catheter for identification of the ureter and a Foley catheter to drain the bladder.

-

Close the anus temporarily with a purse-string suture.

-

Position the patient in the lateral

decubitus position but make the supports loose, so he can be shifted

from a more supine to a more prone position. Do a wide preparation and

drape of the involved extremity, the pelvis, and the lower thorax.

procedure with an anterior part, perineal portion, and posterior

component.

-

For the anterior portion, start the skin

incision at the pubic tubercle and extend it along the inguinal

ligament to the anterior superior iliac spine. From there, follow the

anterior part of the iliac crest eventually to the mid ileum (Figure 120.15.A).![]() Figure 120.15. Hemipelvectomy. See text for details. A:

Figure 120.15. Hemipelvectomy. See text for details. A:

Skin incision. Start the incision at the anterior superior iliac spine

(ASIS) and extend along the inguinal ligament to the pubic tubercle.

Then extend vertically into the perineum to the ischial tuberosity, to

the fold of the gluteus maximus. Follow the gluteal crease laterally to

the greater trochanter and with a gentle anterior curve return to the

ASIS. B: The hemipelvectomy has been completed and the hindquarter detached. C,D: Skin closure. (From Bohne WHO. Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:118–119, Fig. 15-1, Fig. 15-7, Fig. 15-8, with permission.) -

Detach the inguinal ligament as well as

the abdominal muscles from the iliac crest, and develop the space

between the peritoneum and the iliacus muscle. -

Then detach the inguinal ligament and the

rectus abdominus tendon from the pubic bone. In men, retract the

spermatic cord medially. Now enter the space of Retzius and retract the

bladder into the pelvis. -

Doubly ligate and transect the external

iliac artery and veins and cut the femoral nerve back sharply. Now pack

the anterior wound to control hemorrhage and protect the soft tissues. -

For the perineal part, abduct the hip and

extend the incision from the pubic tubercle vertically through the

perineum to the ischial tuberosity. Expose the pubic and ischial rami,

and detach subperiosteally the adductor, hamstring, and perineal

muscles originating from them, as well as the corpus cavernosum. Then

divide the symphysis pubis. Take care not to injure the urethra. -

To complete the posterior part, roll the

patient somewhat forward, and while flexing and adducting the hip,

complete the skin incision by extending it from the ischial tuberosity

laterally along the gluteal crease to the greater trochanter, and from

there superiorly to join the anterior incision at the midiliac crest (Figure 120.15.A).

Expose the posteroinferior margins of the gluteus maximus, incise its

aponeurosis in line with the skin incision, detach its femoral

insertion, and reflect it and the overlying fat and skin as a composite

flap proximally. Identify the gluteus medius, the external rotators of

the hip, and the sciatic nerve. -

Identify, ligate, and sharply transect the sciatic nerve and allow it to retract into the pelvis.

-

Pass a Gigli saw through the greater

sciatic notch; divide the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments and

divide the ileum just lateral to the sacroiliac joint. This is easier

than disarticulating the sacroiliac joint. The joint can be

disarticulated or even a portion of the sacrum resected if required to

establish a surgical margin. -

Then externally rotate the innominate

bone, ligate and divide the obturator vessels and nerve, and transect

the psoas muscle at the level of the sacroiliac joint. Divide the hip

external rotator muscles close to the ischium. -

Transect the levator ani close to its origin on the ischium and the pubis. This will free the hindquarter (Figure 120.15.B).

-

Place a deep and superficial suction

drain and begin closure by bringing the posterior skin and muscle flap

forward and suturing it to the lateral border of the abdominal muscles

and the rectus abdominus muscle. Posteriorly,

P.3166P.3167

secure it to the psoas and quadratus lumborum muscles. Use #0 or #1 absorbable sutures. -

Then close the skin loosely (Figure 120.15.C, Figure 120.15.D).

-

Create the anterior flap by starting an

incision at the anterior superior iliac spine, and extend it along the

lateral aspect of the thigh to the level of the superior pole of the

patella. Then continue the incision transversely across the quadriceps

tendon and medially to the midline, and subsequently proximalward to

the groin (Figure 120.16.A). Figure 120.16. Larsen and Liang (51) modified hemipelvectomy using an anterior quadriceps flap. See text for details. A: Skin incision. B: Remove the innominate bone with osteotomies of the pubic rami and the ileum. C:

Figure 120.16. Larsen and Liang (51) modified hemipelvectomy using an anterior quadriceps flap. See text for details. A: Skin incision. B: Remove the innominate bone with osteotomies of the pubic rami and the ileum. C:

The anterior quadriceps musculocutaneous flap is supplied by the

superficial femoral artery and vein, which are carefully preserved. D: The skin closure. (From Bohne WHO. Atlas of Amputation Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical, 1987:120–124, Fig. 15-9, Fig. 15-10, Fig. 15-13, with permission.) -

Develop the musculocutaneous flap from

lateral to medial by incising the deep fascia and transecting the

quadriceps tendon horizontally. Elevate the quadriceps muscle from the

femur, developing the dissection along the vastus medialis. -

Find the adductor canal, transect the

sartorius muscle and ligate, and transect the femoral vessels as far

distally as possible so that their proximal ends remain with the

musculocutaneous flap. With further proximal dissection, take care not

to injure the femoral vessels. Only the profunda femoris artery is

ligated farther proximally (Figure 120.16.C). -

Then complete the hemipelvectomy as

described previously, but exclude the posterior flap, which is replaced

by the anterior flap. Removal of the innominate bone can be made easier

by osteotomy of the pubic rami rather than by disarticulation of the

pubic symphysis (Figure 120.16.B). -

Closure of the amputation is as described previously (Figure 120.16.D).

patients experience persistent residual extremity pain, swelling, a

sense of instability, and an inability to tolerate extended prosthetic

ambulation. The residual extremity undergoes atrophy as a result of

inactivity and becomes a passive participant in walking. This symptom

complex is referred to as the inactive residual extremity syndrome. The

Ertl osteomyoplastic lower extremity amputation reconstruction is

directed at treating difficult transtibial and transfemoral amputee

symptoms and reversing the inactive residual extremity syndrome (21,22,23 and 24).

Patients in our transtibial and transfemoral series were surgically

reconstructed after nonoperative and prosthetic modifications were

exhausted (22,23,24).

-

Utilize the previous amputation incision

for exposure. Isolate the neurovascular structures, and ligate the

arteries and veins separately. Distract the nerves and cut them well

above the bone level, allowing them to retract into a soft-tissue bed. -

Separate the anterior and posterior

muscle groups, exposing the distal tibia and fibula in preparation for

forming osteoperiosteal cortical island flaps. -

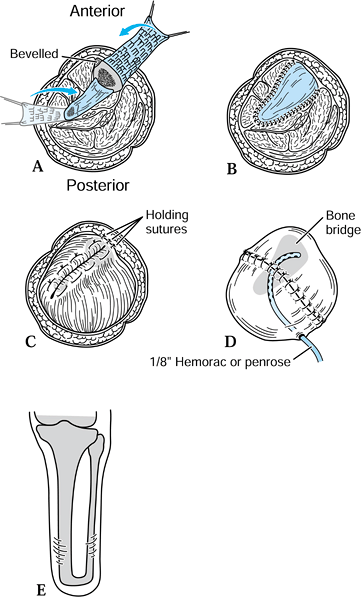

Elevate the osteoperiosteal cortical

island flaps with a 30° to 45° angled chisel from the medial and

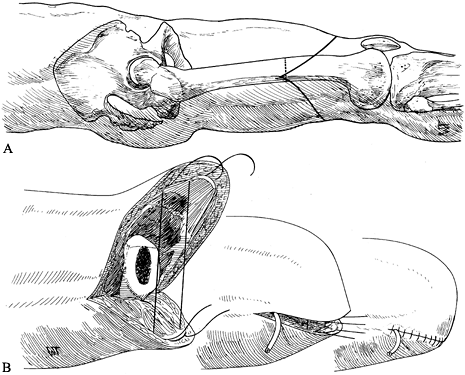

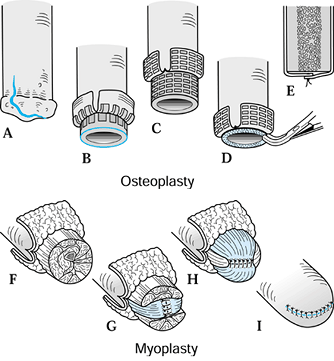

lateral borders of both the tibia and the fibula (Figure 120.17.A).![]() Figure 120.17. Ertl osteomyoplastic transtibial amputation reconstruction. A:

Figure 120.17. Ertl osteomyoplastic transtibial amputation reconstruction. A:

Transverse section of amputation level, with elevated osteoperiosteal

flaps from the medial and lateral aspects of the tibia and fibula. The

roof is created with the interior flaps. B:

The outer osteoperiosteal flaps are folded over the medullary canals

and sutured to one another as well as to the superior flap, forming a

closed tubelike structure (osteoperiosteal bridge) and closing the

medullary canal. C: The opposing muscle

groups are sutured together forming the myoplasty. Muscle rotation may

be necessary to completely cover the bridge and anterior tibia. D: The skin is contoured to the underlying myoplasty, avoiding dog-ear formation, creating a smooth surface and interface. E: Completed transtibial reconstruction with mature bridge and reestablishment of the medullary canal. -

Remove approximately 1.5–2 cm of the end

of the tibia, and suture the retained osteoperiosteal flaps together in

tubelike fashion, forming a bony bridge between the tibia and fibula (Figure 120.17.B). -

To complete the myoplasty, secure the

ends of the opposing muscle groups to each other over the end of the

bone and the underlying bridge, reestablishing some muscle tension (Figure 120.17.C, Figure 120.17.D and Figure 120.17.E). -

Contour the skin to the underlying myoplasty, forming a smooth, cylindrical residual extremity (Figure 120.17.D).

-

Elevate and suture together the

osteoperiosteal cortical island flaps, covering the open-ended

medullary canal. Remove minimal bone after flap elevation (Figure 120.18.A, Figure 120.18.B, Figure 120.18.C, Figure 120.18.D and Figure 120.18.E). Figure 120.18. Ertl osteomyoplastic transfemoral amputation reconstruction. A: A periosteal incision is made. B: Osteoperiosteal flaps are created and elevated. C: The femur is transected below the osteoperiosteal flaps. D: The exposed distal bone surface is freshened with a rongeur. E: The osteoperiosteal flaps are sutured to each other, closing the medullary canal. F: The four major muscle groups are isolated. G: The adductors are sutured to the abductors, incorporating sutures into the periosteal sleeve or through bone holes. H: The extensors are sutured to the flexors, circumferentially covering the medial/lateral myoplasty. I: The skin is contoured to the underlying myoplasty, avoiding dog-ear formation.

Figure 120.18. Ertl osteomyoplastic transfemoral amputation reconstruction. A: A periosteal incision is made. B: Osteoperiosteal flaps are created and elevated. C: The femur is transected below the osteoperiosteal flaps. D: The exposed distal bone surface is freshened with a rongeur. E: The osteoperiosteal flaps are sutured to each other, closing the medullary canal. F: The four major muscle groups are isolated. G: The adductors are sutured to the abductors, incorporating sutures into the periosteal sleeve or through bone holes. H: The extensors are sutured to the flexors, circumferentially covering the medial/lateral myoplasty. I: The skin is contoured to the underlying myoplasty, avoiding dog-ear formation. -

Secure the opposing muscle groups to the

distal periosteum and to each other to reestablish muscle length and to

stabilize the femoral shaft within the muscle envelope (Figure 120.18.F, Figure 120.18.G and Figure 120.18.H).

a mean follow-up of 9 years and a mean time to reconstruction of 9.5

years. We also performed 74 transfemoral reconstructions, with a mean

follow-up of 9.8 years and a mean time to reconstruction of 13.3 years.

A 30-point clinical assessment score was used to rate postoperative

pain, function, stability, swelling, hours able to wear the prosthesis,

and radiographic evaluation. A score of over 25 points was graded as

excellent, 20–24 as good, 15–19 as fair, and less than 15 as poor. In

the transtibial group, there were 73.3% excellent, 18.7% good, 5.3%

fair, and 2.7% poor results, with an overall patient satisfaction of

97%. The transfemoral group had 70% excellent, 20%

good, 4% fair, and 6% poor, with an overall patient satisfaction of 94% (23,24).

has been shown to improve vascularity to the residual extremity and

return an elevated intramedullary pressure to normal (23,24,29,49,54,55).

In the transtibial population, medullary closure stabilizes the fibula

by forming a bony bridge, thus improving the rotational control of the

extremity within the prosthesis. The potential for tolerating end

bearing is also enhanced with medullary closure for both transtibial

and transfemoral patients. Myoplasty has been demonstrated to improve

the arterial supply and venous return of the residual extremity,

benefiting vascular amputees as well (21,22,28,30,31,62).

Additionally, the osteomyoplasty improves extremity control and

strength and can provide a greater surface area for prosthetic fitting.

Other authors have demonstrated a more powerful residual extremity that

is prosthetically more satisfactory (11,16,17 and 18,49,54,55).

directed at generating an active and functional residual extremity by

reestablishing as normal a physiologic environment as possible. It is

our feeling that the resultant residual extremity will provide the

patient with a more durable limb with improved stability and

proprioception. The residual limb is more powerful and prosthetically

provides better adherence to the socket. No unnecessary bone length is

removed to achieve the end result, but we do not hesitate to sacrifice

length when an increase in function can be achieved. We have

successfully applied this reconstruction to both primary and secondary

amputations.

amputation: soft dressings, soft dressings with pressure wrapping,

semirigid dressings (56), and rigid dressings.

Each has advantages and disadvantages. The rigid dressing leads to the

most successful early maturation of the stump. Indeed, in

well-vascularized amputation stumps, the rigid dressing can be combined

with an immediate postoperative fitting that will allow early weight

bearing (8). However, the rigid dressings do not allow easy access to the amputation wound.

(IPOP) can be considered for all levels of the lower extremity

amputation. Use the IPOP with caution in dysvascular amputees, as

excessive pressure may lead to wound necrosis. Potential advantages

include decreased postsurgical edema, a decreased incidence of

thromboembolic disease, less pain, protection of the stump wound, and

earlier mobilization of the patient and fitting of a pylon prosthesis,

which enhances rehabilitation and is psychologically good for the

patient.

the operating room. Cover the wound with a sterile dressing and a

sterile stump sock. Fill the area between the amputation wound and the

cast with either fluffed gauze or a premanufactured polyurethane foam

cup. Pad bony prominences with strips of felt, and over this apply an

elastic plaster-of-paris bandage to gently compress the area of the

amputation wound. In the below-knee amputation, apply the cast to above

the knee and keep the knee at approximately 10° to 20° of flexion.

Incorporate into the cast a suspension strap for a waist belt as well

as an attachment plate for the pylon that holds the prosthetic foot.

not only for the surgeon and prosthetist but also for the physical

therapist who has to supervise the early partial weight bearing (25).

Delay weight bearing in dysvascular amputees. Removable rigid dressings

have been devised. After 2 weeks at the most, remove the circular rigid

dressing for wound inspection and reapplication.

edema. This advantage is lost in soft dressing. If a soft dressing with

pressure wrapping is used, apply the elastic bandage with care to avoid

excessive compression and strangulation of the residual limb.

dressings as for the rigid dressing; however, the outer layer of this

dressing consists of Unna paste bandages, which have to be held in

place with a stockinet. This type of dressing has the same advantage of

preventing excessive postoperative edema as the rigid dressing but does

not allow any attachment of the provisional prosthesis.

occur at a higher incidence than after normal elective surgery when

amputations are performed in the absence of preexisting vascular

disease or infection in the extremity. The incidence of infection,

however, is much higher when amputation is performed in the presence of

active infection in the extremity, particularly when the level of

amputation is close to the site of infection. In dysvascular amputees,

occasionally too distal a level of amputation is selected in spite of

preoperative studies indicating that the level of amputation is

appropriate.

stump complications in amputations performed for open fractures of the

tibia secondary to high-velocity crush injuries,

when

the open fracture wound has gone on to progressive necrosis and

infection. These tend to occur in young active patients, so there is a

tendency to try to preserve a below-knee level, which may lead to

amputation through marginal tissues. The risks of stump wound breakdown

and infection in these cases can be minimized by careful preoperative

workup to ensure that the amputation is occurring through viable

tissue, and by performing staged amputations. The initial stage of the

amputation can be a simple guillotine-type amputation, followed by

definitive amputation with or without primary closure, or the initial

amputation can be with the usual flaps but be left open and then closed

secondarily when it is evident that the tissues are viable and

infection is not present.

infection, but necrosis of wound edges as well as of underlying muscle

can occur in amputation for peripheral vascular disease because of

inadequate vascularity at the level of amputation. Current techniques

for evaluating extremity perfusion (as discussed previously) have

lessened this risk, but in spite of the best of care breakdown still

occasionally occurs. Closure of the wound under tension predisposes to

breakdown. This can be avoided by always closing stumps loosely, since

this allows accommodation for postoperative swelling. If revision of

the level of amputation to a more proximal level may result in loss of

the knee joint or preclude the use of a prosthesis, then reconstructive

options such as free microvascular transfer of tissues and Ilizarov

bone transport methods may be indicated to preserve function in young

active individuals.

are only occasionally painful. Isolating all superficial and deep

nerves, gently applying traction to them, and cutting them with a

sharp, fresh blade to allow them to retract into soft tissue where the

prosthesis will not bear on the nerve end will avoid most problems with

neuromas. Treat neuromas initially nonoperatively, with adjustments of

the prosthesis and desensitizing techniques in physical therapy. If a

neuroma is refractory to nonoperative treatment, explore the nerve, and

transect it higher deep in soft tissues where it will not be a problem.

as well as a physical trauma. One of my patients told me on the day

after the operation, “Part of me has died. When is the rest to follow?”

To overcome this feeling of depression and disability, the amputation

should be undertaken with a view toward the postoperative life of the

patient: The patient must be the most important member of the team that

is undertaking the rehabilitation after the amputation.

end-bearing limb remnant in the very young and the very old is

important. In the growing individual, the reason for the end-bearing

stump is to prevent bony overgrowth, which can require numerous

revisions of the amputation. Also, in our experience, the

patellar-tendon-bearing prosthesis in the growing individual often

leads to the development of a patellar alta, which in turn, is

frequently the cause for recurrent dislocation of the patella. In the

very old, the end-bearing prosthesis makes rehabilitation considerably

easier, and ultimately the prosthesis is more comfortable than after

diaphyseal amputations.

The new prosthetic components have made the use of the below-knee

prosthesis easier and more satisfactory than in times gone by. Indeed,

many of our younger patients have returned to high-achievement sports.

In older below-knee amputees, energy consumption is much more favorable

than in above-knee amputees of similar age, allowing them to

participate in physical activities with greater ease.

much of the limb as possible as long as the disease process allows, is

highly desirable. In lower extremity amputations, this is particularly

obvious when comparing internal hemipelvectomy with hindquarter

amputation.

scheme: *, classic article; #, review article; !, basic research

article; and +, clinical results/outcome study.

SB, Henriksen BM, Holstein PE. Minor Amputaions on the Feet after

Revascularization for Gangrene. A Consecutive Series of 95 Limbs. Acta Orthop Scand 1997;68:291.

J. Ertl Osteomyoplastic Lower Extremity Amputation Reconstruction:

Technique and Long Term Results. Presented at the annual meeting of the

American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons, San Francisco, CA, Feb.

17, 1997.

C. Muscle Blood Flow after Amputation with Special Reference to the

Influence of Osseous Plugging of the Medullary Cavity. Acta Orthop Scand 1976;47:613.

JM, Abdu WA, Mayor MB. Reconstructive Amputation after Grade IIIC Open

Tibial Fracture. One Method of Preserving residual Limb Length. J Orthop Trauma 1994;8:354.

D, Howery T, Sanders R, Johansesn K. Limb Salvage versus Amputation:

Preliminary Results of the Mangled Extremity Severity Score. Clin Orthop 1990;256:80.

R, Betz AM, Cometet JJ, Berger AC. Decision Making and Results in

Subtotal and Total Lower Leg Amputations: Reconstruction versus

Amputation. Microsurgery 1995;16:830.

A, Allen A, Luff R, McColl I. Rehabilitation after Lower Limb

Amputation: A Comparative Study of Above-Knee, Through-Knee, and

Gritti-Stokes Amputations. Br J Surg 1989;76:622.

H, Poole G, Hansen F, et al. Salvage of Lower Extremities Following

Combined Orthopedic and Vascular Trauma: A Predictive Salvage Index. Am J Surg 1987;53:205.

J, Wood D, Hornby R, et al. The Measurement of Skin Blood Flow in

Peripheral Vascular Disease by Epicutaneous Application of 133 Xenon. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1976;58:833.

F, Christiansen J, Ebskov B. Prevention and Treatment of Ulceration of

the Foot in Unilaterally Amputated Diabetic Patients. Acta Orthop Scand 1982;53:481.

J, Agardh CD, Apelqvist J, Stenstrom A. Clinical Characteristics in

Relation to Final Amputation Level in Diabetic Patients with Foot

Ulcers: A Prospective Study of Healing Below or Above the Ankle in 187

Patients. Foot Ankle Int 1995;16:69.

HE. Biological and Biomechanical Principles in Amputation Surgery.

Prosthetics International. Proceedings of the Second International

Prosthetics Course, Copenhagen, 1962.

M, Stahlgrew L. Evaluation of Factors which Influence Mortality and

Morbidity following Major Lower Extremity Amputation for

Atherosclerosis. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1965;120:1217.

K, Bernon G, Katz R, et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Osteogenic

Sarcoma: Results of a Cooperative German/Austrian Study. J Clin Oncol 1984;2:617.