Muscular Dystrophies

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Muscular Dystrophies

Muscular Dystrophies

Paul D. Sponseller MD

Description

-

Muscular dystrophies are a group of

inherited disorders characterized by progressive degeneration and

weakness of skeletal muscle without apparent cause in the nervous

system. -

Skeletal and cardiac muscles are affected, and secondary effects occur in the lungs, skeleton, and many other systems.

-

These conditions have been categorized by

clinical distribution, severity of muscle weakness, and pattern of

genetic inheritance. -

Because of limited space, only Duchenne muscular dystrophy is described in detail (Fig. 1).

-

Classification:

-

Sex-linked muscular dystrophy: Duchenne muscular dystrophy, Becker, Emery-Dreifuss

-

Autosomal-recessive muscular dystrophy: Limb-girdle, infantile fascioscapulohumeral

-

Autosomal-dominant muscular dystrophy: Fascioscapulohumeral, distal, ocular, oculopharyngeal

-

Epidemiology

Incidence

-

Duchenne muscular dystrophy occurs in young boys.

-

Duchenne muscular dystrophy occurs in 1 in 3,500 live male births (1).

-

Becker dystrophy occurs in ~1 in 30,000 live male births (1).

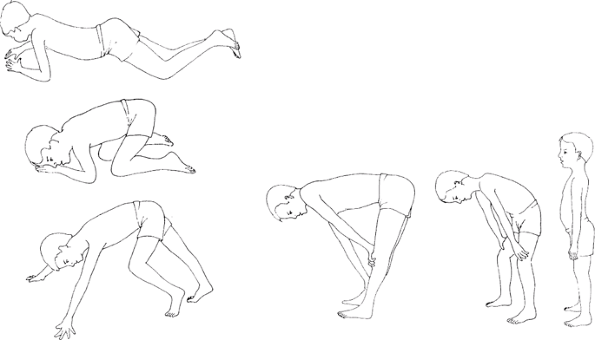

Fig. 1. This series of 6 drawings illustrates the Gower maneuver of a 7-year-old child with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Fig. 1. This series of 6 drawings illustrates the Gower maneuver of a 7-year-old child with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Risk Factors

Male gender

Genetics

-

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is sex-linked, as is Becker-type tardive dystrophy.

-

Other dystrophies are autosomal recessive and autosomal dominant.

Etiology

-

A single gene defect in the short arm of

the X chromosome has been identified as being responsible for Duchenne

muscular dystrophy and Becker muscular dystrophy.-

The gene encodes the protein dystrophin, which is a component of the cell membrane cytoskeleton.

-

Signs and Symptoms

-

Duchenne muscular dystrophy:

-

The disease occurs only in males, and it usually becomes evident at 3–6 years of age.

-

Common presentations include:

-

Delayed walking

-

“Waddling,” Trendelenburg gait, or lordotic gait

-

Frequent tripping and falling

-

Inability to hop and jump

-

-

Progressive weakness occurs in the

proximal muscle groups, including the gluteus, quadriceps, abdominal

muscles, and shoulder girdle muscles -

Pseudohypertrophy and contracture of calf muscles is common.

-

Most patients have cardiac involvement, most commonly tachycardia and right ventricular hypertrophy.

-

Many also have static encephalopathy with mental retardation.

-

Death from pulmonary and cardiac failure occurs during the 2nd or 3rd decade of life.

-

Because of hip muscle weakness, patients

compensate by carrying the head and shoulders behind the pelvis during

gait, thus producing an anterior pelvic tilt and increased lumbar

lordosis. -

Weakness in the shoulder girdle occurs 3–5 years after presentation.

-

It is difficult to lift the patient under the arms because of the weakness.

-

This weakness has been termed the “Meryon” sign.

-

-

No sensory deficits are detected.

-

Children usually are unable to ambulate effectively beyond 10 years of age.

-

-

Becker muscular dystrophy:

-

Similar to Duchenne muscular dystrophy in clinical appearance and distribution of weakness, but less severe

-

The onset usually occurs after the age of 7 years.

-

The rate of progression is slower than in Duchenne muscular dystrophy

-

-

Many more types of muscular dystrophy exist (not described here).

P.267

Physical Exam

-

History, physical examination,

measurement of creatine phosphokinase and dystrophin, and

electromyography help in making the diagnosis. -

Electromyography shows a myopathic pattern, with reduced amplitude, short duration, and polyphasic muscle action potentials.

-

Muscle biopsy also may be performed.

-

Evaluate muscle bulk to assess for pseudohypertrophy of the calves.

-

Observe the patient’s gait and look for Trendelenburg gait.

-

Starting proximally, look for muscle weakness.

-

Evaluate the patient’s ability to stabilize the shoulder; test for Meryon sign.

-

Note contracture, developing later, followed by scoliosis.

Tests

Lab

-

Serum creatine phosphokinase markedly is elevated in the early stages of Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

-

It may be 200 times normal, but it later declines as muscle degeneration becomes complete.

-

-

Dystrophin levels are completely absent in Duchenne muscular dystrophy; they are less than normal in Becker dystrophy.

Pathological Findings

-

Muscle degeneration, with subsequent loss of fibers

-

Variation in fiber size

-

Proliferation of connective tissue

Differential Diagnosis

-

Peripheral neuropathy

-

Anterior horn cell disease

-

Poliomyelitis

General Measures

Most patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy die in

their 2nd or 3rd decade of life; therefore, orthopaedic treatment

should be designed to improve or maintain the functional capacity of

the involved adolescent.

their 2nd or 3rd decade of life; therefore, orthopaedic treatment

should be designed to improve or maintain the functional capacity of

the involved adolescent.

Activity

-

No restrictions on activity.

-

Activity is to be encouraged as much as possible.

Special Therapy

Physical Therapy

-

Test muscle strength to assess the rate of deterioration.

-

Use ankle-foot orthoses for correctable deformities.

-

The best treatment for fractures is closed reduction and immobilization.

-

Fractures of the lower extremities occur

frequently in children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, especially in

children who are wheelchair bound. -

Contractures of both lower and upper extremities may occur.

-

Surgical release of contractures sometimes is indicated to improve function.

-

-

~95% of patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy develop progressive scoliosis (2).

-

Surgical correction of scoliosis improves sitting balance and minimizes pelvic obliquity.

-

Posterior spinal fusion is recommended for curves of >20–30°.

-

-

Programs of vigorous respiratory therapy

and the use of home negative-pressure and positive-pressure ventilators

may promote life extension. -

Proper diagnosis and early genetic

counseling may help parents to be aware of the risk of additional male

infants with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Medication

-

No drugs have been proved effective.

-

Steroids have some benefit (delaying

scoliosis and prolonging function), but they also are associated with

long-term problems, including weight gain and osteoporosis.

Surgery

-

Contracture release (Achilles, fascia lata) may be indicated.

-

Correction of scoliosis involves fusion of nearly the entire thoracic and lumbar spine (T2–L5 or sacrum).

-

Rods are used to straighten and hold the spine.

-

This intervention should be performed for curves of ≥30°.

-

Prognosis

-

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is fatal in the 2nd or 3rd decade of life.

-

Becker dystrophy is more slowly progressive, and life expectancy is greater.

Complications

-

Respiratory failure

-

Cardiac failure

-

Fracture

-

Scoliosis

Patient Monitoring

Patients must be followed frequently (every 4–6 months) by a neurologist to assess their progression.

References

1. Alman BA, Raza SN, Biggar WD. Steroid treatment and the development of scoliosis in males with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Bone Joint Surg 2004;86A:519–524.

2. Biggar WD, Gingras M, Fehlings DL, et al. Deflazacort treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Pediatr 2001;138:45–50.

Codes

ICD9-CM

359.1 Duchenne muscular dystrophy

Patient Teaching

Genetic counseling is important, to warn of the risk of additional affected infants.

FAQ

Q: What is the benefit of scoliosis surgery in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy?

A: It improves sitting balance and prevents discomfort that develops as the spine collapses.