Compartment Syndrome

defined as an enclosed space formed by fascia, or a combination of

fascia and bone, that contains one or more muscles. An exception to

this definition is the carpal tunnel, which contains nine flexor

tendons but no muscle—except for those individuals with low-lying

muscle fibers from the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) that

sometimes extend into the carpal canal. The contents of an anatomic

compartment are muscles, arteries, veins, and nerves.

defined as a symptom complex resulting from increased tissue pressure

within a limited space that compromises the circulation and function of

the contents of that space. This occurs when intramuscular pressure is

elevated to a level, and for a period of time, sufficient to reduce

capillary perfusion.

undergoes necrosis, fibrosis, and contracture; associated nerve injury

causes further muscle dysfunction, sensibility deficits, or chronic

pain. The end result is a dysfunctional muscle compartment with local

and distant manifestations that depend upon the compartment involved

and the degree of muscle contracture and nerve dysfunction.

pressure (IMP) exceeds capillary blood pressure for a prolonged period

of time. In this circumstance, immediate decompression is required to

prevent muscle necrosis.

to cause ischemia, pain, and in some instances, diminished sensibility

or neurological dysfunction.

by tighter-than-normal fascia, small increases of volume associated

with exercise may significantly increase IMP.

neurologic deficit for a sufficient period of time, an acute

compartment syndrome may result. This condition is seen most often in

the lower extremity, but it also may occur in the upper extremity.

of irreversible hypoxic damage to muscles, nerves, and vascular

endothelium of an anatomic compartment. It may be categorized as mild,

moderate, or severe. In its mild form,

portions of normal muscle are replaced by contractile scar tissue that

shortens or contracts the affected muscle. The adjacent nerves are not

affected and the resultant deformity may be minimal.

muscle or muscles are more severely involved, and the adjacent nerves

may be affected to some degree. The end result is a more significant

deformity involving the FDS and flexor pollicis longus (FPL)—and in

some instances, portions of the FDS muscles and the median nerve.

the digital flexors are involved, along with the extrinsic wrist

flexors. In some cases, the muscles in the extensor and mobile wad

compartment are also involved. The median nerve is severely

compromised, and often degenerates into a fibrous tissue thread at its

midaspect. Although less likely to be involved, the ulnar nerve may

also be compromised. The end result is a severe flexion contracture of

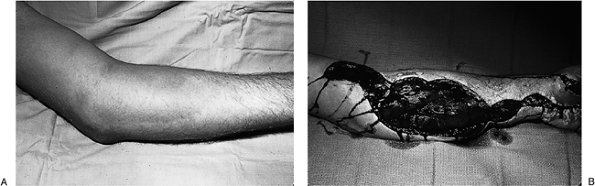

the wrist and digits, with significant sensory deficit. Figure 15-1 depicts the clinical and intraoperative appearance of Volkmann’s ischemic contracture.

the shoulder to the hand. They are the deltoid, anterior arm, posterior

arm, mobile wad of the forearm, flexor forearm, extensor forearm, and

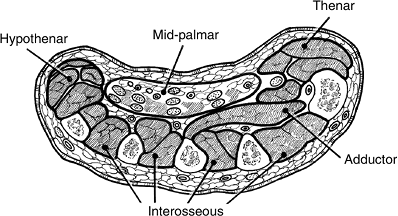

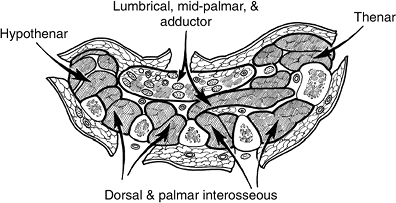

pronator quadratus. In the hand they

include

the central palmar, adductor, thenar, hypothenar, interosseous, and

finger compartments. The central palmar compartment contains the

lumbrical muscles, and thus meets the definition of a compartment. The

finger or digits, although not a definite compartment, may require

release if they are significantly compromised by both internal and

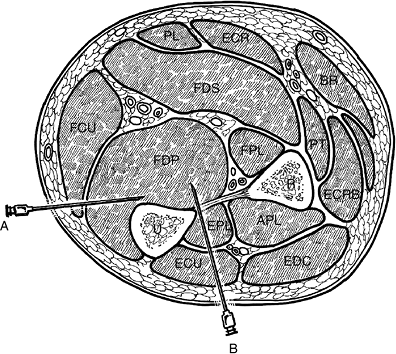

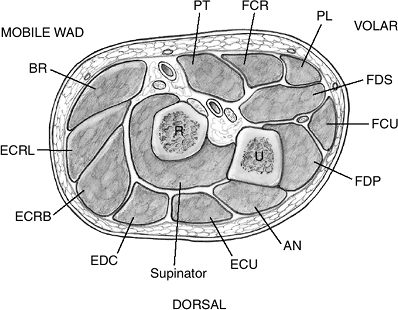

external pressure. The flexor forearm (Figure 15-2) and the interosseous (Figure 15-3) compartments have the greatest clinical significance, since development of a compartment

syndrome in these two locations probably results in the most significant functional loss and deformity.

|

|

Figure 15-1 Clinical and intraoperative appearance of Volkmann’s ischemic contracture in an elderly alcoholic. A. Note the fixed and flexed wrist, the adduction contracture of the thumb, and the claw deformity of the fingers. B. Note the necrotic muscle at the tip of the forceps. C. The median nerve was surrounded by necrotic muscle (Penrose drain).

|

|

|

Figure 15-2

The three forearm compartments: the flexor containing the finger, thumb, and wrist flexors; the extensor containing the finger, thumb, and ulnar wrist extensor (ECU); and the mobile wad of three, which is represented by the brachioradialis and the ECRL and ECRB (radial wrist extensors). R, radius; U, ulna. |

|

|

Figure 15-3 Cross section of the midpalm, depicting the thenar, adductor, interosseous, midpalmar, and hypothenar spaces.

|

|

|

Figure 15-4 Matsen’s unified concept of compartment syndrome (see text for details).

|

-

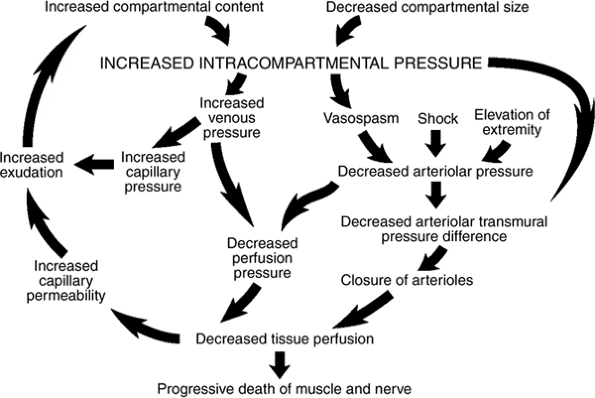

Compartment syndrome is caused by elevated pressure inside a closed compartment.

-

Matsen’s unified concept of compartment syndrome is presented in Figure 15-4.

-

Increased pressure within a compartment

may be caused by either an increased volume within the compartment

(such as fracture, hemorrhage, soft-tissue injury, and snake bite) or a

decrease in the size of the compartment (such as a tight cast or

dressing, burn eschar, or prolonged external limb pressure during

anesthesia or during an unconscious state resulting from drugs or

alcohol). -

In children, supracondylar fractures of

the humerus are a frequent cause because of a cast that fits tightly,

or an injury or occlusion of the brachial artery. -

Because of the relatively noncompliant

nature of the fascia around the specific anatomic compartments, either

of these two situations will result in an increase in pressure. -

Increased pressure within a compartment decreases the blood supply to the soft tissues, resulting in tissue hypoxia and damage.

-

The blood flow is determined by several

factors, including arterial pressure, venous pressure, resistance

within the vessel, and local tissue pressure. -

The difference between the arterial and venous pressures is the arteriovenous gradient.

-

This gradient, and therefore blood flow,

will be decreased if venous pressure is increased or if the incoming

arterial blood pressure is decreased (such as in shock, hemorrhage, or

limb elevation). -

All blood vessels, but particularly the microcirculation

and veins, are collapsible. Blood flow, therefore, also can be

decreased if the surrounding tissue pressure exceeds both the strength

of the vessel wall and the pressure within the vessel.

-

-

Tissue pressure affects both the flow

through a vessel, and the fluid equilibrium and exchange across the

walls of the microcirculation. -

Both the fluid pressure within the

capillary and the surrounding tissues, and the respective osmotic

pressures within the tissue and plasma, determine fluid exchange.

are given in Box 15-1. Compartment syndrome must be distinguished from

arterial injury and nerve injury. Table 15-1,

based on five of the six Ps, helps to differentiate compartment

syndrome from the ischemia associated with arterial injury or from the

findings in nerve injury that might mimic some of the components of

compartment syndrome.

-

The diagnosis of forearm compartment

syndrome is made by clinical findings, and may be confirmed by

measurement of intracompartmental pressure.

-

Pressure (elevated)

-

Pain (especially with passive stretch of the involved muscle[s])

-

Paresthesia

-

Paresis or Paralysis

-

Pink skin color

-

Pulse (usually intact)

-

Clinical findings include the following:

-

A swollen, tense, tender compartment with overlying skin that is often pink or red (Figure 15-5).

-

Pain that may seem out of proportion to the injury.

-

Sensory deficits or paresthesias.

-

Paresis or paralysis.

-

Distal pulses are usually intact.

-

-

Pain is usually increased by passive

stretch of the muscles in the affected compartment. For pain in the

flexor forearm compartment, stretching regimens would include passive

extension of the wrist and finger flexors.-

This finding may not be specific or reliable if there is an associated fracture or blunt trauma.

-

-

Sensory changes usually occur before motor deficits.

-

Radial and ulnar pulses are usually

intact, since systolic arterial pressure (+/- 120 mm Hg) exceeds the

pressure within the involved compartment.

-

-

If the extremity is swollen, Doppler examination may be useful to determine the status of the pulse.

-

Pink or red discoloration of the skin may

be absent, and temperature, capillary refill, and compartment turgor

may not be reliable signs in many instances. -

In children, anxiety associated with an increasing analgesic requirement is a very reliable indicator of compartment syndrome.

|

Table 15-1 Differential Diagnosis of Compartment Syndrome, Arterial Injury, and Nerve Injury Based On Five P’s

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

-

Although the diagnosis of compartment

syndrome may be made clinically, the measurement of the

intracompart-mental pressure is an additional diagnostic tool that may

aid in confirmation of the diagnosis. -

Compartment pressures can be measured by

the needle manometer technique, continuous infusion technique, the wick

or slit catheter technique, or with transducers that measure pressures

digitally. -

Self-contained devices with instructions

for use, such as the Stryker and Whitesides pressure monitor, are

commercially available. -

It is important to become familiar with

at least one of these techniques or devices so that the necessary tools

may be readily located in your emergency department, clinic, or

hospital, and utilized in a timely fashion. -

The threshold pressures considered

consistent with a compartment syndrome range from 45 mm Hg to 20 mm Hg

below diastolic pressure. -

Animal studies of compartment syndrome

have indicated that clinical signs along with compartment pressures of

30 mm Hg or greater are consistent with compartment syndrome. Figure 15-5 Acute compartment syndrome of the forearm. A.

Figure 15-5 Acute compartment syndrome of the forearm. A.

This patient was obtunded from drugs. He lay on his left arm/forearm

for an unknown length of time; note the swelling in the forearm and

arm. He complained of severe pain. B. He

was immediately taken to the operating room, where a comprehensive

fasciotomy was performed, which revealed swollen and edematous forearm

muscles. -

Figure 15-6 demonstrates ulnar and dorsal approaches for needle placement in the flexor aspect of the forearm.

-

The carpal tunnel, although not a true

compartment, may act as a closed space, and the median nerve may be

subject to the adverse effects of increased pressure. -

The hand compartments that may be

involved in compartment syndrome are the interosseous (both dorsal and

palmar), the thenar and hypothenar, the adductor, and the fingers. -

The clinical findings in compartment

syndrome in the hand are similar to the previously described findings

in the forearm, and include pain in the region, pain with passive

stretch of the involved muscles, localized swelling, paresthesia in the

involved nerve distribution, and muscle paresis. -

In the hand, all the intrinsic muscles

may be evaluated by passively abducting and adducting the digits with

the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints in extension and the proximal

interphalangeal (PIP) joints in flexion. -

The adductor compartment in the thumb is

tested by positioning the thumb in palmar abduction to produce

stretching of the adductor. -

The thenar muscles are stretched by

abduction and extension of the thumb, and the hypothenar muscles are

stretched by abduction and extension of the little finger.![]() Figure 15-6

Figure 15-6

Ulnar and dorsal approaches for needle/catheter placement in the flexor

forearm to obtain intracompartmental pressure. The starting point for

both approaches is at the junction of the proximal and middle third of

the supinated forearm. A. The ulnar approach inserts the needle/catheter into the deep or profundus compartment using the ulna as a guide. B.

The dorsal approach permits measurement of the dorsal compartment

pressures, as well as the deep compartment depending on the depth of

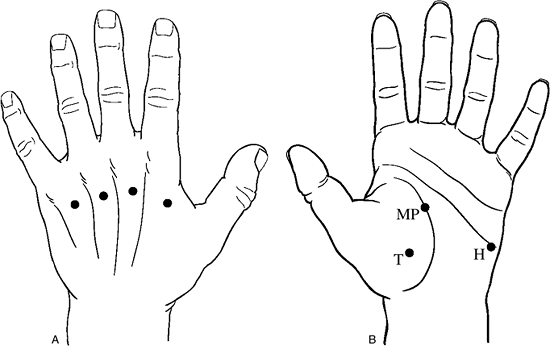

insertion. R, radius; U, ulna. Figure 15-7 Portals for compartment pressure measurements in the hand. A. Interosseous compartment pressures may be measured through these four portals on the dorsum of the hand. B. The thenar (T), midpalmar (MP), and hypothenar (H) compartments may be measured through these portals.

Figure 15-7 Portals for compartment pressure measurements in the hand. A. Interosseous compartment pressures may be measured through these four portals on the dorsum of the hand. B. The thenar (T), midpalmar (MP), and hypothenar (H) compartments may be measured through these portals. -

Swelling and increased tissue turgor may be noted over the individual involved compartments.

-

In the fingers, the amount of swelling

and the nature of the injury—as well as the presence of a nonyielding

burn eschar—may indicate increased pressure and the need for a

fasciotomy. -

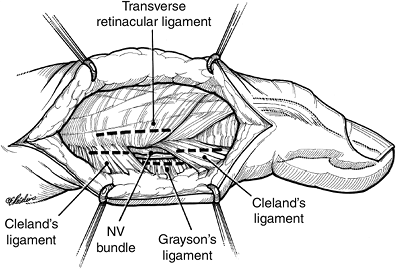

Potential compartments are present in the

finger due to the presence of fascial bands around the neurovascular

bundles, including Grayson’s and Cleland’s ligaments.

-

Figure 15-7 depicts the sites of needle placement for measurement of compartment pressures in the hand.

-

The goals of treatment are to restore microcirculation to the compartment through decompression.

-

This includes splitting or removing a

tight cast, including the removal of cast padding and tight dressings

or bandages of any type down to the level of the skin. -

If these maneuvers fail to resolve the problem, then immediate operative decompression is performed.

-

Decompression is typically achieved by fasciotomy.

|

|

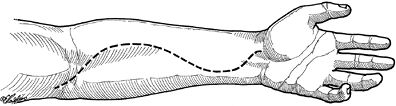

Figure 15-8

Comprehensive incision for release of the volar forearm compartment syndrome. Note that the incision includes the distal arm and should include the carpal tunnel. |

-

The forearm compartments (involving the

forearm flexor compartment and the mobile wad compartment) are

decompressed by a comprehensive incision from the distal arm to the

midpalm, as noted in Figure 15-8 and 15-5B. -

The deep fascia is incised from the region of the distal arm to, and including, the carpal canal.

-

The underlying flexor muscles will often bulge dramatically into the wound.

-

-

The median nerve is at risk at four

locations: the lacertus fibrosus, the pronator teres, the deep fascial

arcade of the flexor digitorum superficialis, and the carpal tunnel. -

If preoperative findings indicate that

the ulnar nerve is involved, it is also decompressed as indicated at

the cubital tunnel, forearm, and Guyon’s canal at the wrist and hand. -

If signs of radial nerve dysfunction are present, decompression of the radial tunnel may also be indicated (see Chapter 7, Entrapment Neuropathies, for details of radial nerve decompression).

-

Coexisting forearm fractures are usually stabilized operatively at the time of fasciotomy.

-

Skin incisions are left open to accommodate swelling, but are loosely reapproximated to cover the nerves.

-

If fractures are open and contaminated, fasciotomy is performed, wounds debrided, and fractures stabilized.

-

In contaminated wounds, external fixation or limited internal fixation may be preferable to standard internal fixation methods.

-

Skin grafting and limited secondary closure is performed when wounds demonstrate clean granulation tissue.

-

Compartment syndromes involving the forearm extensor compartment are released through a dorsal incision.

-

When both the flexor and extensor

compartments are involved, it is preferable to release the flexor

compartment first; the relaxation afforded by the skin and fascia often

decompresses the dorsal compartments. -

Dorsal compartment pressures are used to determine whether or not to release the extensor compartment.

-

If required, it is released through a

longitudinal incision 2 cm lateral and distal to the lateral

epicondyle. The incision is continued distally to the myotendinous

junction of the extensor muscles in the midforearm.

-

-

Fasciotomy is also indicated at the time of limb revascularization if the duration of ischemia has been as much as 4 to 6 hours.

-

Post revascularization edema may precipitate compartment syndrome, and prophylactic fasciotomy is indicated.

-

The principles of treatment of hand compartment syndromes are similar to those of the forearm.

-

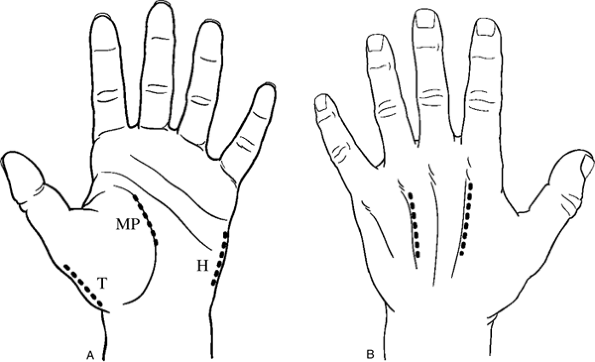

The appropriate incisions for decompression of the various hand compartments are depicted in Figure 15-9.

-

The essentials of the deeper dissection for decompression of the hand compartments are given in Figure 15-10.

-

Release of swollen fingers may be required based on the amount of swelling and the nature of the skin envelope.

-

If a significant burn eschar or swelling

is present, digital fasciotomies are performed through midlateral

incisions on the nondominant or noncontact side of the digits. The

incisions are dorsal to the neurovascular bundles; Cleland’s and

Grayson’s ligaments are incised. -

The dissection usually ends at the flexor sheath.

-

The incision is centered over the PIP joint and may extend 2 cm proximal and 2 cm distal to the PIP joint, as described in Figure 15-11.

-

The prognosis depends on the intensity and duration of the elevated compartment pressure.

Figure 15-9 Appropriate incisions for release of the hand compartments. A. The thenar (T), midpalmar (MP), and hypothenar (H) incisions. B. Suitable incisions for release of the interosseous compartments.

Figure 15-9 Appropriate incisions for release of the hand compartments. A. The thenar (T), midpalmar (MP), and hypothenar (H) incisions. B. Suitable incisions for release of the interosseous compartments. -

Therefore, time is of the essence in the management of compartment syndrome.

-

If clinical findings and/or pressure

readings are suggestive, but not conclusive, remember that the scar

from a fasciotomy incision is of relatively minimal consequence

compared to an untreated compartment syndrome that results in a

Volkmann’s ischemic contracture.

|

|

Figure 15-010

Depiction of the details of the deeper dissection for release of the interosseous muscle compartments, the thenar compartment, the midpalmar and adductor compartments (both of which may be released through a midpalmar incision), and the hypothenar compartment. |

-

Treatment goals are to increase function,

decrease associated pain factors if present, and, if possible, restore

limb sensibility.

|

|

Figure 15-11 Midaxial incision for release of compromised digits in compartment syndrome.

|

-

Treatment of mild contractures depends upon the severity of the deformity and the time interval between injury and initiation of treatment.

-

Contractures of the deep forearm flexors,

with normal hand sensibility and preservation of remaining extrinsic

muscle strength, are treated by a comprehensive hand rehabilitation

program that includes active and passive mobilization, strengthening,

and static and dynamic extension splinting. This regimen works to

improve thumb web space width, strengthen weak thumb intrinsic muscles,

and correct or improve digital flexion contractures.

-

Treatment of moderate to severe

contractures is based on elimination of contractures, release of

secondary nerve compression, and tendon transfers to recover some of

the lost function. -

The surgical procedures employed include

excision of the muscle infarct, tendon lengthening, muscles slides,

neurolysis (or nerve graft in very severe cases), and various tendon

transfers to restore balance and function. -

Microvascular free tissue transfers of nerve and muscle have been promising in severe cases of Volkmann’s contracture.

AR, Mubarak SJ. Current concepts in the pathophysiology, evaluation and

diagnosis of compartment syndrome. Hand Clinics 1998;14:371–383.

CG, Johnson GHF. A new technique of catheter placement for measurement

of forearm compartment pressure. J Trauma 1991;31:1404–1408.

SJ, Hargens AR, Owen CA, et al. The wick-catheter technique for

measurement of intramuscular pressure. A new clinical and research

tool. J Bone Joint Surg 1976;58A:1016–1020.

K. Management of established Volkmann’s Contracture. In: Green DP,

Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, eds. Green’s operative hand surgery. 4th Ed.

New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1999:593–603.

Schroeder HP, Botte MJ. Definitions and terminology of compartment

syndrome and Volkmann’s ischemic contracture of the upper extremity.

Hand Clin 1998;14:331–341.

TE Jr, Heckman MM. Acute compartment syndrome: update on diagnosis and

treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1996;4:209–218.