CHAPTER 33 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 33 – Arthroscopic Treatment of Elbow Stiffness

Alfred Cook, MD

Limitation of elbow motion can arise from a variety of causes, including acute or chronic trauma, heterotopic ossification, spasticity, burn scar contracture, and postoperative scarring. Inflammatory conditions as well as intraarticular lesions can cause decreased motion about the elbow. Examples of these lesions include osteophytes on the olecranon and coronoid processes, loose bodies, adhesions, synovitis, osteochondritis of the capitellum, and chondromalacia of the radial head.[6] Multiple techniques have been developed and employed to address these various pathologic processes. Several open techniques have been described to address elbow stiffness, such as a limited anterior capsulotomy with or without tenotomy as well as distraction arthroplasty, all of which have been effective. [3] [8] [15] These methods, however, tend to be technically demanding, and patients undergo significant morbidity and prolonged rehabilitation. Several authors have described and reported on arthroscopic techniques to address limited elbow motion. Authors have described arthroscopic release of the anterior capsule, removal of loose bodies, excision of osteophytes, and débridement of the olecranon fossa, either alone or in some combination. [4] [6] [9] [12] [14] The goal of all these techniques is to regain motion from 30 to 130 degrees. We focus on the arthroscopic management of the stiff elbow.

Patients present with complaints of limited range of motion and occasionally a history of trauma. It is commonly seen in men with a history of heavy use of the arm, weight lifters, and throwing athletes. These patients can present in the third to eighth decade, depending on the cause. Athletes and patients with osteochondritis dissecans present earlier. The history is characteristically one of mechanical impingement and pain at the extremes of motion (extension greater than flexion). The patient may complain of pain while carrying a briefcase secondary to the arm’s being extended. A flexion contracture of 30 degrees is common.[9]

It is important to inspect the skin for signs of obvious pathologic changes, such as burns. The patient’s range of motion is documented and characterized. Is there a hard or soft endpoint? Is the arc of motion painful versus pain at the extremes of motion? Answers to these two questions can provide significant information concerning the etiology of the stiff elbow. When a soft endpoint is present, this probably represents a soft tissue constraint, whereas a hard endpoint is more consistent with bone impingement. Pain during the arc of motion represents an internal derangement from joint incongruity or degeneration. However, if there is pain at the extremes of motion, bone impingement is usually present.

A thorough neurovascular examination should be performed. Ulnar nerve function should be critically evaluated. Chronic contractures can damage the ulnar nerve and compromise function. In addition, the ulnar nerve is investigated for subluxation or dislocation anteriorly. This can occur in 16% of the population, and the ulnar nerve will be at risk for injury with anterior medial portal placement.[9]

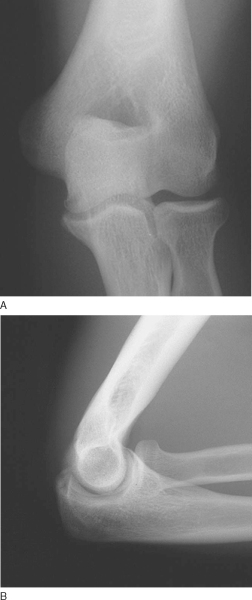

Combined with the history and physical examination, standard radiographs should be obtained. Anteroposterior and lateral views are usually sufficient (

Fig. 33-1

). The lateral view is especially helpful in delineating osteophyte involvement and appreciating any deformity in the olecranon or coronoid fossa. Radiographs also help identify loose bodies. A computed tomographic scan may offer information about the radiocapitellar and ulnar-trochlear articular surfaces.[9] We find magnetic resonance imaging helpful in visualizing the three-dimensional anatomy of the joint, in particular for the preoperative determination of planned amount of osteophyte resection and fossa deepening.

|

|

|

|

Figure 33-1 |

Indications for elbow arthroscopy include evaluation of the painful elbow, evaluation and treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum, evaluation and treatment of osteochondral lesions of the radial head, and partial synovectomy. Specifically, treatment of early degenerative changes of the elbow that limit motion (i.e., olecranon and coronoid fossa osteophytes) with arthroscopy has been shown to be successful. With more advanced changes, an open approach is more appropriate because it is faster, technically easier, and more effective. In addition, contractures of the elbow and the removal of loose bodies can effectively be addressed with the use of arthroscopy.[12]

Contraindications to elbow arthroscopy are few but include an active infection in the region of planned surgery as well as bone ankylosis or severe fibrous ankylosis that prevents safe introduction of the arthroscope. Previous surgery that alters the normal anatomy, such as an ulnar nerve transposition, may limit portal selection. In addition, the intracapsular space is severely constricted in stiff elbows. Thus, the space in the anterior elbow is reduced. With this in mind, capsular distention is important to ensure that neurovascular structures are away from the operative area. Excessive distention of soft tissues will limit the time available for the operation. In severely stiff elbows, adequate distention may not be able to be achieved and the risk of neurovascular injury is too significant to proceed. An open procedure should be considered at that point. [2] [9] Finally, arthroscopic capsular release is one of the most technically demanding and potentially risky of the arthroscopic procedures in the elbow, and the experience of the surgeon must guide the procedure.

Options for positioning of the patient include supine, prone, and lateral decubitus on a standard operating room table. A tourniquet is applied as high on the upper arm as possible to control bleeding. General anesthesia is usually administered because it allows complete muscle relaxation and eliminates intraoperative discomfort for the patient. Regional anesthesia can be given if the patient is supine; a major disadvantage is the inability to perform an accurate neurovascular examination after the operation. Local anesthesia is also an option and advantageous given that it allows the patient to communicate with the surgeon when instruments are placed near neurovascular structures. However, it does not allow the use of a tourniquet and should be avoided for longer arthroscopic procedures.[2]

When a supine position is used, the patient’s arm is positioned so that it hangs free off the side of the table in a suspension device, with the shoulder in neutral rotation and 90 degrees of abduction and the elbow in 90 degrees of flexion. This position allows excellent access to both sides of the elbow and relaxes the neurovascular structures of the antecubital fossa. Standard arthroscopic portals can be employed.[2]

Although initially the preferred position for this procedure was supine, many surgeons prefer the lateral decubitus or prone position. Both positions offer similar convenience for the surgeon, with the prone position perhaps offering better access to the elbow. The prone position provides the added advantages of easier joint manipulation, improved access to the posterior aspect of the joint, and more complete viewing of the intraarticular structures. The patient is placed prone on chest rolls, and a tourniquet is applied to the proximal aspect of the arm. An arm board is placed parallel to the operating room table. The shoulder and arm are then elevated on a sandbag that is placed on the arm board. The arm is then allowed to hang. No traction is needed. The arm is positioned so that the shoulder is in neutral rotation and 90 degrees of abduction. The elbow is flexed to 90 degrees with the hand pointing toward the floor. After positioning, the arm is prepared and draped in the normal sterile fashion, and bone landmarks and portals are outlined. Laterally, the lateral epicondyle and radial head are outlined; medially, the medial epicondyle is marked; and posteriorly, the olecranon tip is identified. The portals can then be defined.[2]

The lateral decubitus position was developed as a modification to the prone position. This position allows easy access to the posterior compartment and permits excellent management of the airway by anesthesia. The patient is held in this position with a beanbag and kidney rests. A tourniquet is applied, and the arm is placed over a bolster. The bolster should let the arm hang with the elbow in 90 degrees of flexion and provide unobstructed access to the anterior and posterior portals.[2]

Surgical Landmarks, Incisions, and Portals

The most commonly used portals for elbow arthroscopy are the direct lateral, proximal medial, anterolateral, anteromedial, posterolateral, and straight posterior portals (

Fig. 33-2

). The direct lateral (midlateral) portal is located at the “soft spot,” which is formed by the triangle between the lateral epicondyle, olecranon, and radial head. This site is used for distention of the elbow. It can also be used as a working portal for access to the posterior chamber of the elbow when the patient is prone. This portal also allows access to the posterior aspect of the capitellum as well as the radiocapitellar and radioulnar joints. The posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerve is most at risk with this portal. It passes within an average of 7 mm of the portal. [1] [9]

|

|

|

|

Figure 33-2 |

The proximal medial (superomedial) portal has also been described. It is located approximately 2 cm proximal to the medial humeral epicondyle and just anterior to the intermuscular septum. The arthroscopic sheath is introduced anterior to the intermuscular septum while contact is maintained with the anterior aspect of the humerus. The trocar is then directed toward the radial head. This portal provides excellent visualization of the anterior compartment of the elbow including the radiocapitellar joint. The median nerve is potentially at risk when this portal is established. However, this portal is potentially safer than the anteromedial portal because the more proximal portal permits the cannula to be directed distally. This allows the cannula to be directed almost parallel to the median nerve in the anteroposterior plane. [1] [9]

Several lateral portals have been described, with the safer portals located more proximally to avoid the radial nerve. The anterolateral portal is 3 cm distal and 2 cm anterior to the lateral humeral epicondyle and lies in the sulcus between the radial head and capitellum anteriorly. This portal provides excellent visualization of the medial plica, coronoid process, trochlea, coronoid fossa, and medial capsule. Superficially, the posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerve is at risk and lies approximately 2 mm from the cannula. The radial nerve is also at significant risk. It can lie as close as 3 mm from the cannula. [1] [9] Stothers et al[13] compared a proximal lateral portal established 1 to 2 cm proximal to the lateral epicondyle with the standard distal anterolateral portal in cadaveric specimens and found that this proximal portal was safer and provided improved visualization, especially of the radiohumeral joint. We recommend the use of this portal instead of the anterolateral portal.

The anteromedial portal is made 2 cm distal and 2 cm anterior to the medial humeral epicondyle and passes through the common flexor origin. The anterior branch of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve and the median nerve are at risk. When the cannula is placed, the elbow should be flexed. In this position, the brachialis acts to protect the nerve. This portal provides excellent visualization of the radiocapitellar and humeroulnar joints, the coronoid fossa, the capitellum, and the superior capsule. [1] [9]

The posterolateral portal is located 2 to 3 cm proximal to the tip of the olecranon at the lateral border of the triceps tendon. The trocar is directed toward the olecranon fossa. This portal provides excellent visualization of the olecranon tip, olecranon fossa, and posterior trochlea, but the posterior capitellum is not well seen. The medial and posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerves are the two structures at risk, passing an average of 25 mm from the portal. The ulnar nerve is at risk if the cannula is placed too far medial. The nerve is approximately 25 mm from the portal. [1] [9]

The direct posterior portal is located 1 to 2 cm directly proximal to the tip of the olecranon, through the triceps. The trocar is directed to the olecranon fossa. The ulnar nerve is at risk if the cannula is placed too far medially.

Specific Steps (

Box 33-1

; authors’ preference)

For the pathologic changes that occur with degenerative or posttraumatic elbow contractures to be adequately addressed, the anterolateral, anteromedial, and posterior portals are used. Before the patient is positioned, an examination under anesthesia is performed. The range of elbow motion is documented. The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position with the operative extremity over a bolster or in an arm holder. A tourniquet is applied and is used at the surgeon’s discretion. The arm is prepared and draped with an Ace wrap on the hand and forearm. Bone landmarks as well as the course of the ulnar nerve are outlined. Preoperatively, the ulnar nerve should be assessed for subluxation. The full range of excursion of the nerve should be marked out and avoided during surgery. Alternatively, the nerve can be dissected and protected through an open approach before arthroscopic releases are performed.

The elbow is distended by injection of fluid into the joint through the posterolateral soft spot. The elbow should extend slightly as the capsule is distended. Free fluid return through the needle should also be observed. We typically start with the anteromedial portal as described before, using a spinal needle directed toward the radiocapitellar articulation. The free flow of fluid should be observed from the spinal needle if the location of the needle is intraarticular. The spinal needle indicates the correct angle for trocar placement. The skin is then incised, and a small clamp is used to separate the subcutaneous tissues. A blunt trocar and cannula are introduced into the elbow, following the angle established by the spinal needle. Again, free flow of fluid should be observed from the trocar if it is intraarticular. If the joint capsule is adherent to the anterior humerus, a gentle sweeping motion with the trocar can elevate the anterior capsule and make a larger working space. The proximal lateral portal is used to enter the joint, with a spinal needle as a finder. Diagnostic arthroscopy is performed. Loose bodies are removed, and osteophytes are removed by a bur or shaver with minimal or no suction. It is helpful to preserve the capsule initially during removal of osteophytes to maintain distention and to protect anterior neurovascular structures. Loose bodies are often found at the proximal capsule attachment to the humerus or adjacent to the radiocapitellar joint.

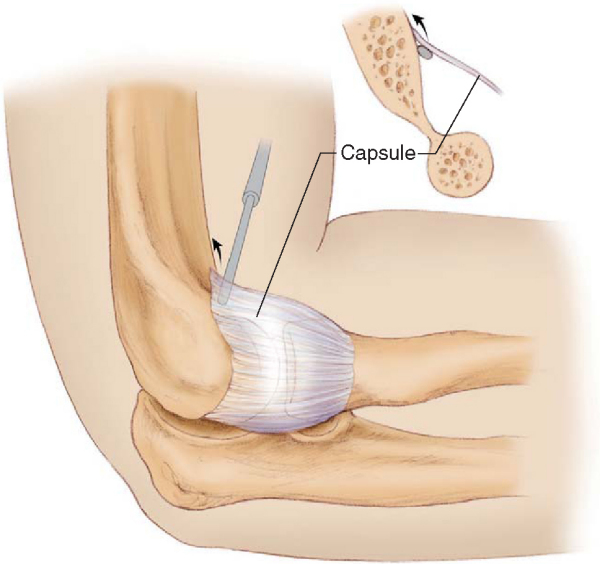

If the anterior capsule is contracted, it is released from medial to lateral near the proximal anterior attachment, where the brachialis protects the neurovascular structures (

Fig. 33-3

). Because the radial nerve may lie almost directly on the distal lateral capsule, this area should be avoided. Capsulotomy can be performed by a basket or a duckbill hand instrument turned so that the tissue is visualized within the jaws of the instrument. This allows precise control of the tissue being divided. We prefer this to mechanical shavers or radiofrequency devices. On occasion, we use a blunt probe through an accessory portal to retract anterior tissues.

After the anterior procedures, the posterior ulnohumeral joint is carefully evaluated for a mechanical block. If a block is noted, posterolateral and direct posterior portals are established, and the olecranon fossa and tip of the olecranon are débrided with a mechanical shaver or bur to remove any osteophytes or excessive bone. Medially, the ulnar nerve is at risk, and great care must be taken in resecting tissue in this area, with use of minimal or no suction. A ⅛-inch osteotome can be introduced through the posterior portal to resect the olecranon tip. Extending the elbow can deliver the tip of the olecranon to the resection instrument and can evaluate adequacy of resection. Loose bodies can often be found in the posteromedial and posterolateral gutters.

In cases of severe motion restriction, particularly loss of pronation and supination, partial or complete arthroscopic radial head resection can be performed. The radiocapitellar joint can be visualized through the anteromedial portal and resected through the proximal lateral portal. Malunions may also involve the posterior portion of the radial head, which can be visualized through a well-placed posterior or posterolateral portal with the elbow in some extension and resected through the posterior soft spot portal. On occasion, the scope can be placed in the soft spot portal. A switching stick is used to place the visualization cannula in the correct position.

The final range of motion is evaluated, and the portals are sutured closed to avoid prolonged drainage or sinus formation. A compressive dressing is placed on the elbow, and the Ace bandage is removed.

The patient is instructed to start elbow motion as tolerated. The patient is also instructed to keep the elbow elevated to minimize swelling. If a synovectomy or débridement was performed, or if postoperative bleeding is expected, the limb can be splinted in full extension in a padded Jones dressing with an anterior slab of plaster and suspended vertically for 36 hours to minimize bleeding and edema. This position leaves the least volume of space available for swelling to occur. Another option is to use continuous passive motion postoperatively.[9] Gates et al[3] investigated the use of continuous passive motion after performing an anterior capsulotomy without tenotomy of the biceps tendon or myotomy of the brachialis muscle for posttraumatic flexion contracture. The patients were divided into two groups (one with continuous passive motion and one without). They found that although the postoperative use of continuous passive motion did not significantly improve mean active extension, it did improve active flexion and the total arc of motion. Postoperatively, we place these patients in a soft bulky dressing for 1 or 2 days, followed by an aggressive physical therapy protocol designed to promote range of motion.

Most complications of elbow arthroscopy are neurovascular in nature. Many authors have reported various neurovascular injuries secondary to multiple causes, including overdistention of the capsule, direct injury by instruments, and injury during portal placement. [1] [7] [10] Kelly et al[5] retrospectively reviewed 414 elbow arthroscopies that had been performed for osteoarthritis, loose bodies, and rheumatoid or inflammatory arthritis. Procedures performed during these arthroscopies included synovectomy, débridement of articular surfaces or adhesions, excision of osteophytes, diagnostic arthroscopy, loose body removal, and capsular procedures (such as capsulotomy, capsulectomy, and capsular release). Serious complications such as joint space infection occurred in four patients (0.8%). Minor complications occurred in 50 (11%) of the procedures. These complications included prolonged drainage, persistent minor contracture of 20 degrees or less, and 12 transient nerve palsies. The most significant risk factors for the development of a temporary nerve palsy were an underlying diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and a contracture. There were no permanent nerve injuries, hematomas, or compartment syndromes. All minor complications, with the exception of residual contractures, resolved without sequelae.[10]

| PEARLS AND PITFALLS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Results of arthroscopic approaches to elbow stiffness have rivaled those of open approaches (

Table 33-1

). In addition, arthroscopic treatment has the added benefit of less morbidity and earlier rehabilitation.[14] Phillips and Strasburger[12] treated 25 patients with limited range of motion, 10 secondary to degenerative arthritis and 15 secondary to posttraumatic arthrofibrosis. They performed a capsular release, removal of loose bodies, débridement of fibrotic tissue, and removal of osteophytes limiting motion. The patients obtained a significant increase in their range of motion. Koh et al[7] treated 17 patients with elbow stiffness secondary to posttraumatic contractures, osteoarthritis, and hemophiliac arthropathy. These patients underwent an arthroscopic débridement, capsular release, and removal of loose bodies. All patients demonstrated improved elbow motion postoperatively, and 15 had improved arc of motion postoperatively. Overall good to excellent results were achieved in 88% of patients. There were no neurovascular complications.

| Author | Followup | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Timmerman and Andrews[14] (1994) | Average: 29 months | 79% good–excellent results with arthroscopic débridement |

| Phillips and Strasburger[12] (1998) | Average: 18 months | All 25 patients showed statistically significant increases in motion and decreased pain |

| Koh et al[7] (1999) | Average: 25 months | 88% good–excellent results with arthroscopic débridement |

| Kim et al[6] (1995) | Average: 25 months | 92% of patients satisfied with arthroscopic débridement with increased range of motion and improved elbow scores |

| Jones and Savoie[4] (1993) | Average: 22 months | All patients were satisfied with their results and demonstrated decreased pain and improvement in range of motion |

| Ogilvie-Harris et al[11] (1995) | Average: 35 months | All 21 patients demonstrated good–excellent results Pain, strength, motion, stability, and function improved significantly with arthroscopic treatment |

An arthroscopic approach to the stiff elbow provides reliable improvement in a patient’s elbow range of motion. It is associated with less morbidity for the patient and earlier postoperative rehabilitation. Although damage to neurovascular structures is of concern, an arthroscopic approach is a safe and effective surgery to address the stiff elbow.

1.

Baker CL, Jones GL: Arthroscopy of the elbow. Current concepts.

Am J Sports Med 1999; 27:251-264.

2.

Canale ST, Phillips BB: In: Canale ST, ed. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics,

10th ed.. St. Louis: Mosby; 2003:2613-2665.

3.

Gates III HS, Sullivan FL, Urbaniak JR: Anterior capsulotomy and continuous passive motion in the treatment of posttraumatic flexion contracture of the elbow.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992; 74:1229-1234.

4.

Jones GS, Savoie III FH: Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow.

Arthroscopy 1993; 9:277-283.

5.

Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW: Complications of elbow arthroscopy.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83:25-34.

6.

Kim SJ, Kim HK, Lee JW: Arthroscopy for limitation of motion of the elbow.

Arthroscopy 1995; 11:680-683.

7.

Koh J, Parsons B, Hotchkiss RN, Altchek DW. Arthroscopic débridement and capsulotomy for restricted elbow motion. Presented at the 26th annual meeting of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, 1999.

8.

Morrey BF: Posttraumatic contracture of the elbow. Operative treatment, including distraction arthroplasty.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990; 72:601-618.

9.

O’Driscoll SW: Arthroscopic treatment for osteoarthritis of the elbow.

Orthop Clin North Am 1995; 26:691-706.

10.

O’Driscoll SW, Morrey BF: Arthroscopy of the elbow. Diagnostic and therapeutic benefits and hazards.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992; 74:84-94.

11.

Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Gordon R, MacKay M: Arthroscopic treatment for posterior impingement in degenerative arthritis of the elbow.

Arthroscopy 1995; 11:437-443.

12.

Phillips BB, Strasburger S: Arthroscopic treatment of arthrofibrosis of the elbow joint.

Arthroscopy 1998; 14:38-44.

13.

Stothers K, Day B, Regan WR: Arthroscopy of the elbow: anatomy, portal sites, and a description of the proximal lateral portal.

Arthroscopy 1995; 11:449-457.

14.

Timmerman L, Andrews JR: Arthroscopic treatment of posttraumatic elbow pain and stiffness.

Am J Sports Med 1994; 22:230-235.

15.

Urbaniak JR, Hansen PE, Beissinger SF, Aitken MS: Correction of posttraumatic flexion contracture of the elbow by anterior capsulotomy.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1985; 67:1160-1164.