Total Elbow Arthroplasty for Rheumatoid Arthritis

IV – Elbow Reconstruction > Part C – Operative Treatment Methods

> 59 – Total Elbow Arthroplasty for Rheumatoid Arthritis

inflammatory disorder in which the body’s immune system mistakes

articular cartilage for foreign (nonself) material. The exact cause for

RA is unknown. Genetic susceptibility is recognized, including

monozygotic HLA DR4, which has a 12% to 15% concordance rate. Women,

especially postpartum and those breastfeeding, have an increased risk

along with smokers.

are affected with rheumatoid arthritis, or approximately 1 per 300,000.

It is generally believed that the ratio of women to men is between 2 to

1 and 3 to 1. It is rare in men younger than the age of 45 years; in

this age group, the condition is predominately among women (6 to 1).

The peak incidence is between the ages of 20 and 50 years, but it can

affect both the young and the elderly. Its prevalence is lowered among

black African and Chinese and among certain Indian tribes. It most

commonly affects adults as a polyarticular disease where

extra-articular features are uncommon.

-

Synovitis—The

synovial lining of the joint is congested and at times villous.

Subsynovial infiltrates of lymphocytes and plasma cells are present.

The effusion is cellular, and the capsule is thickened. -

Joint destruction—Within

the first 2 years, proteolytic enzymes and direct invasion of the

pannus of granulation tissue destroys the articular surface. The joint

margins are eroded by the same process. Tendon sheaves develop

tenosynovitis, and this process causes invasion of the collagen bundles. -

Deformity—Over

time, joint destruction capitula thickening and distension along with

tendon rupture leads to progressive instability and deformity.

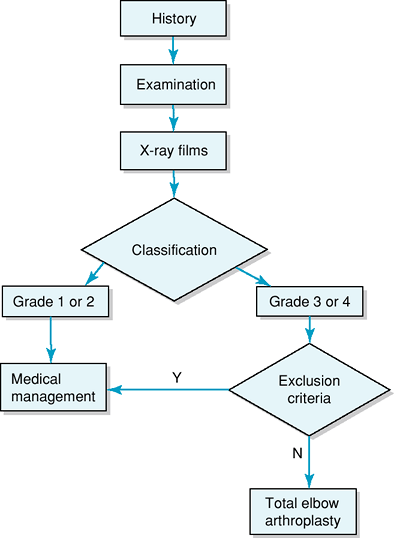

This classification system is based on both the pathologic changes and

the changing x-ray film appearances. This classification system can be

used to guide the orthopaedist with regard to treatment options.

seven revised American Rheumatism Association (ARA) criteria in the

last 6 months.

history to focus on pain, associated stiffness, and/or instability. One

should inquire about neurologic symptoms, especially that of the ulnar

nerve, remembering that approximately 40% of rheumatoid arthritic

patients with elbow pathology have either clinical or subclinical

peripheral neuropathy or nerve compressions. Previous surgery to the

elbow (radial head excision or replacement and/or interposition) has

prognostic implications. A more general view of the patient including

the joints above and below the elbow and cervical spine in mode and

abilities and ambulation is important. The overall functional capacity,

e.g., the ARA classification, may also be useful.

|

TABLE 59-1 Classification of Rheumatoid Arthritis of the Elbow

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

-

The integument—the

skin, especially posteriorly where the incision will be made. The

muscles, the flexors of the elbow: What are their strengths, and what

is their condition? Neurovascular considerations, particularly to the

course of the ulnar nerve and its behavior in flexion. -

The joint—the

range of motion and both flexion and extension along with

pronation/supination; its stability in reference to whether the joint

is enlocated or whether it remains subluxed or flail. -

The patient—particular

reference to the joints above and below (wrist and shoulder), the

cervical spine, and the patient’s general ambulatory ability and if the

affected elbow is used in ambulation in any way (cane, crutch, or

wheelchair).

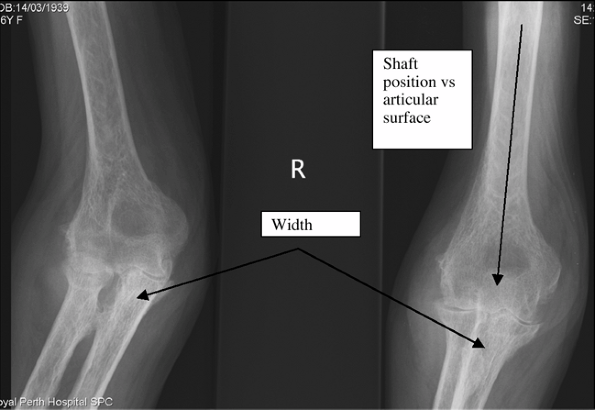

specifically, one should examine the plain x-ray films to determine

surgical requirements. Canal capacity length and alignment relative to

the articulate surfaces are important. Any bone thinning, particularly

cortical bone thinning, especially at points of entry of the prosthesis

or at the tips of potential prosthetic replacement, needs to be noted (Fig. 59-1).

|

TABLE 59-2 Severity of Rheumatoid Arthritis Of the Elbow

|

||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Figure 59-1 Diagnostic workup algorithm.

|

surgical goal is the relief of pain. Total elbow arthroplasty for

rheumatoid arthritis should be considered in patients with grade 3 or 4

disease. The contraindications are bone or joint infection or an open

wound about the elbow. Relative contraindications include the medical

state of the patient specifically with regard to Parkinsonian or other

neurologic disorders, particularly if the patient has a history of

recurrent falls. The possibility that anaesthesia will place the

patient at unnecessary risk must also be considered. The other relative

risk is bone ankyloses. The technical demands of joint replacement at

the elbow are such that the general orthopaedist should refer to those

surgeons with high-volume experience in total elbow arthroplasty.

unconstrained and semiconstrained joint replacements are currently

available. Traditionally, unconstrained joint replacement (with which

there is no direct linkage between the humeral and ulnar components)

has been considered for those patients with grade 3 disease where there

is still primary ligamentous stability. Semiconstrained implants have a

loose linkage between the humeral and ulnar components, allowing

approximately 7 to 10 degrees of toggle at the articulation but at the

same time maintaining the articulation’s

stability. This type of prosthesis is the most commonly used and may be considered for both grade 3 and grade 4 patients.

|

|

Figure 59-2 Anteroposterior radiograph of an elbow with rheumatoid arthritis.

|

history and examination, the orthopaedist having satisfied himself or

herself that the patient is a surgical candidate and has no

contraindications. The examination can specifically review those

aspects important for the joint replacement itself—soft tissue coverage

and the quality of the integument: There must be at least one flexor of

antigravity power and preferably an extensor of similar power both for

extension and to cover the prosthesis. Bone deficiency is covered both

clinically and on the radiographs; the minimum requirement for a

semiconstrained prosthesis is two tubes of bone (the humeral canal, the

ulnar canal, and a grade 4 flexor). These are the minimum requirements

for undertaking elbow replacement arthroplasty.

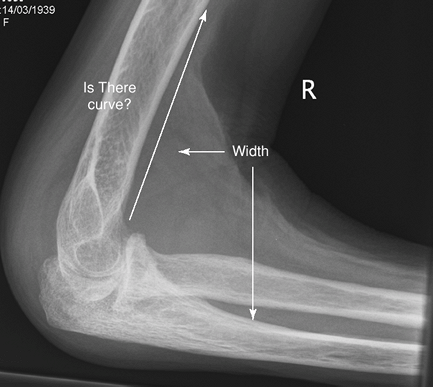

clinic appointment, focuses the orthopaedist on any technical

difficulties of implantation of the preferred implant. The size, the

position of the humeral and ulnar cuts, and the relationship of the

intramedullary canals to the articular surface are brought to the

orthopedist’s attention. Also of note is the curvature of the humerus

on lateral view and therefore its relationship to the prosthesis being

used and the narrowing on lateral view of the ulna beyond to the

olecranon with specific reference to the stem of the prosthesis to be

used (Figs. 59-2 and 59-3).

replacement arthroplasty is covered in other chapters. Important steps

to be focused on include the following:

-

Exposure

-

Ulnar nerve identification and transposition

-

Dislocation

-

Release of anterior humerus

-

Accurate identification of the canals

-

Bone cuts as per manufacturer requirements

-

Trial components; Ensure soft tissue releases for balance of prosthesis

-

Cement prosthesis (sequentially is recommended)

-

Rearticulation

minor and permit easy recovery. Intraoperative bone fracture, either

that of the condyles or perforation of the canals, can occur without

careful preoperative planning. If there is canal perforation, more

distant neurovascular structures such as the radial or median nerve are

at risk. Early complications include wound-healing difficulties,

bleeding, and joint stiffness. Temporary paresthesia, particularly of

the ulnar nerve, is also recognized. Late complications that have been

recognized and should be considered are loosening of the implant’s

bushing in those implants using bushings, triceps failure, and

component fracture. Infection of total elbow arthroplasty in rheumatoid

patients is said to be approximately 2%, which is slightly higher than

that of standard lower extremity (hip and knee) joint replacement.

|

|

Figure 59-3 Lateral radiograph of an elbow with rheumatoid arthritis.

|

patients with rheumatoid arthritis is a 100-degree arc motion generally

from approximately 30 degrees of fixed flexion to 130 degrees of

flexion. The patient should expect excellent relief of pain, which

provides a high degree of satisfaction. When scored by a common elbow

evaluation rating at 10 years, 85% of patients will have a good or

excellent result. The survivor rate is approximately 92% at 10 years

for this group of patients.

commercial or plaster of Paris splint until the following day. This

achieves a decrease in elbow joint volume and therefore reduces

swelling. Thermal regulation that caused the joint may also be used to

reduce the initial swelling. Typically, once the dressings are removed,

simple dressings are applied to the wound, a compressive long arm

stocking is applied, and unrestricted elbow motion can be commenced.

Discharge of the patient from the hospital is dependent on overall

recovery as semiconstrained implants are stable from the beginning and

no specific postoperative splinting is required. If an unconstrained

implant is chosen, the manufacturer’s specific recommendations must be

followed regarding postoperative splinting and protection.

arthritis requires specific restrictions in use of the limb and can be

summarized as follows: no more than 5 kg repeated lifting and no more

than 10 kg in a single event.

DRJ, Morrey BF. The Coonrad-Morrey total elbow arthroplasty in patients

who have rheumatoid arthritis. A ten to fifteen-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1327.

D, Claydon P, Stanley D. Total elbow replacement using the Kudo

prosthesis. Clinical and radiological review with five- to seven-year

follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:354.

J, O’Driscoll S, Morrey BF. Periprosthetic humeral fractures after

total elbow arthroplasty: treatment with implant revision and strut

allograft augmentation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:1642.