Sternoclavicular Joint Injuries

injuries are discussed as injuries that can essentially be managed with

a sling and swathe.41 The first case reports of sc injury are attributed to Rodrigues166

who described a patient with posterior dislocation presenting with

signs of suffocation following a compression injury between a wall and

a cart. Isolated nineteenth century reports in Europe were followed by

those of American authors in the 1920s and 1930s.55,118

SC joint injuries are uncommon and are usually relatively benign

injuries. However, the more severe posterior injury patterns can

represent true medical emergencies and require the orthopaedic surgeon

to be knowledgeable regarding the proper steps in diagnosis and

treatment. Computed tomography (CT) scan remains the imaging modality

of choice. Early and prompt reduction is indicated for posterior

dislocations and posterior physeal injuries. A variety of

reconstructive techniques are available if needed, but are rarely

required.

dislocation of the SC joint. Because the SC joint is subject to

practically every motion of the upper extremity and because the joint

is small and incongruous, one would think that it would be the most

commonly dislocated joint in the body. However, the ligamentous

supporting structure is strong and so designed that it is, in fact, one

of the least commonly dislocated joints. A traumatic dislocation of the

SC joint usually occurs only after tremendous forces, either direct or

indirect, have been applied to the shoulder.

|

|

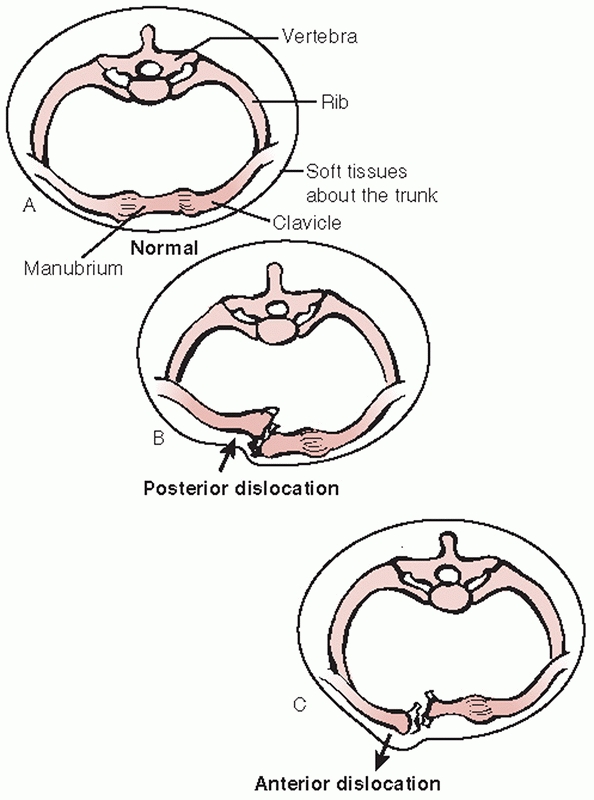

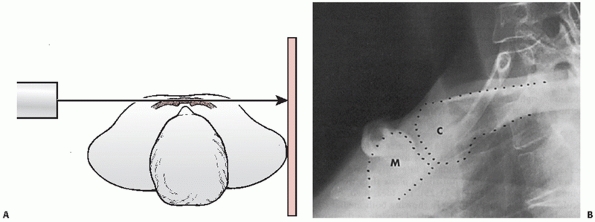

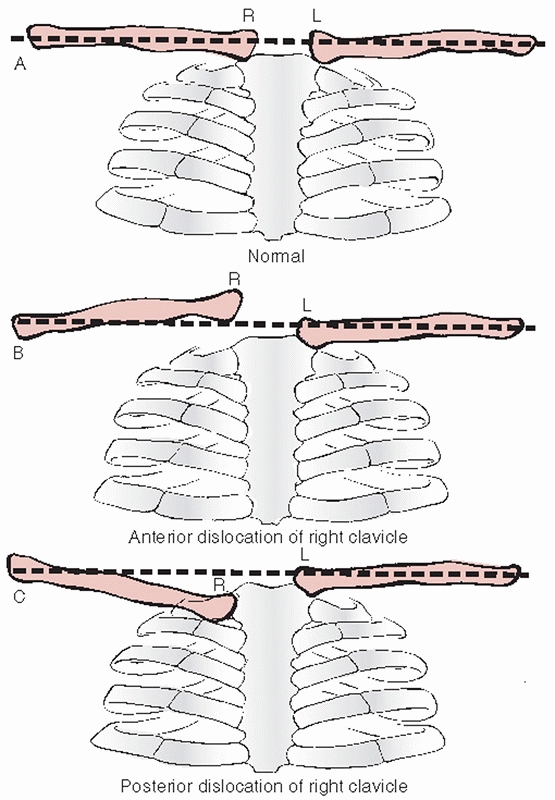

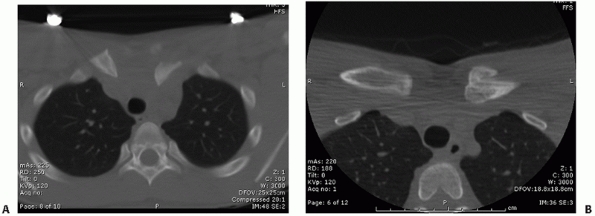

FIGURE 40-1 Cross sections through the thorax at the level of the SC joint. A. Normal anatomic relations. B. Posterior dislocation of the SC joint. C. Anterior dislocation of the SC joint.

|

aspect of the clavicle, the clavicle is pushed posteriorly behind the

sternum and into the mediastinum (Fig. 40-1).

This may occur in a variety of ways: an athlete lying on his back on

the ground is jumped on and the knee of the jumper lands directly on

the medial end of the clavicle, a kick is delivered to the front of the

medial clavicle, a person lying supine is run over by a vehicle, or a

person is pinned between a vehicle and a wall (Fig. 40-2). Anatomically, it is essentially impossible for a direct force to produce an anterior SC dislocation.

|

|

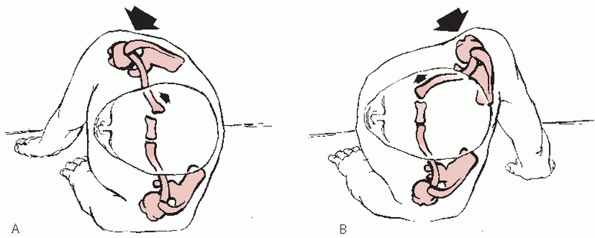

FIGURE 40-3 Mechanisms that produce anterior or posterior dislocation of the SC joint. A.

If the patient is lying on the ground and a compression force is applied to the posterolateral aspect of the shoulder, the medial end of the clavicle will be displaced posteriorly. B. When the lateral compression force is directed from the anterior position, the medial end of the clavicle is dislocated anteriorly. |

|

|

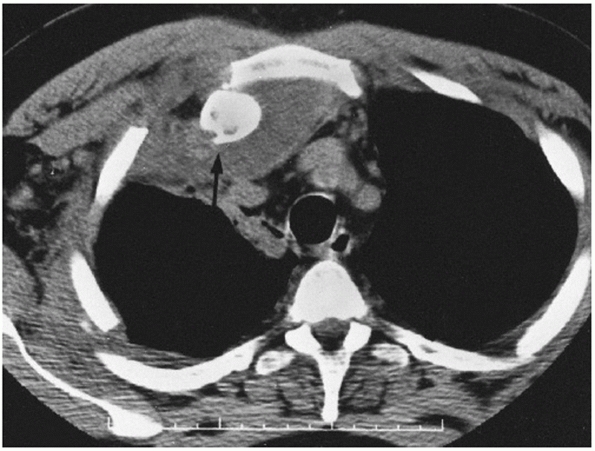

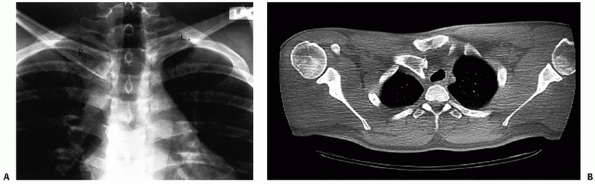

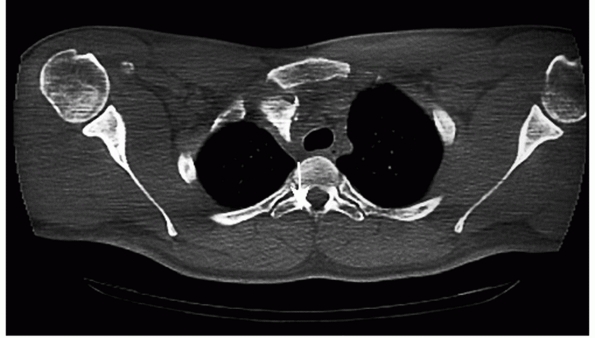

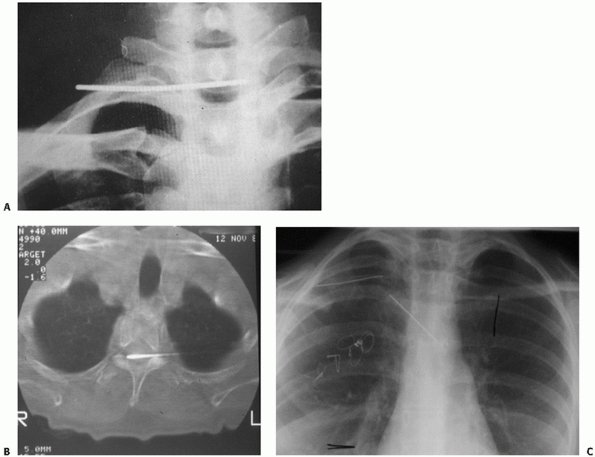

FIGURE 40-2

Computed axial tomogram of a posterior SC joint dislocation that occurred when the driver’s chest impacted the steering wheel during a motor vehicle accident. The steering wheel was fractured from the driving column and the vehicle was totally destroyed. |

the anterolateral or posterolateral aspects of the shoulder. This is

the most common mechanism of injury to the sternoclavicular joint.

Mehta and coworkers131 reported that three of four posterior SC dislocations were produced by indirect force, and Heinig86

reported that indirect force was responsible for eight of nine cases of

posterior SC dislocations. If the shoulder is compressed and rolled

forward, an ipsilateral posterior dislocation results; if the shoulder

is compressed and rolled backward, an ipsilateral anterior dislocation

results (Fig. 40-3).

vehicular accidents; the second is an injury sustained during

participation

in sports.139,143,195 Omer,143

in his review of patients from 14 military hospitals, found 82 cases of

SC joint dislocations. He reported that almost 80% of these occurred as

the result of vehicular accidents (47%) or in athletics (31%).

is 3%. (Specific incidences in the study were glenohumeral dislocations

at 85%, acromioclavicular injuries 12%, and SC injuries 3%.) In the

series by Cave et al.,38 and in our experience, dislocation of the SC joint is not as rare as posterior dislocation of the glenohumeral joint.

showed that injuries involving the shoulder complex accounted for 39.1%

of upper extremity injuries and 11.4% of all alpine skiing injuries. Of

the 393 injuries involving the shoulder complex, SC separations

accounted for 0.5%.

reviewed 18 cases of SC dislocations, none of which were posterior.

However, in our series of 185 traumatic SC injuries, there were 135

patients with anterior dislocation and 50 patients with a posterior

dislocation.

the critical surrounding structures in the neck and thorax and/or by

other musculoskeletal injuries. Significant concomitant injuries of the

mediastinum must be considered to avoid catastrophic outcomes. These

injuries almost always occur in the setting of posterior SC fractures

and dislocations and include:

-

Tracheal compression: from the initial case report of Rodriques166

to multiple case reports in recent articles, the trachea can be

displaced by the posteriorly displaced medial aspect of the clavicle.

Acute airway compromise or subacute dyspnea are key symptoms.121,137 -

Pneumothorax: pleural violation by the

clavicle has been noted with SC dislocation and should be especially

considered in high-energy direct trauma.147 -

Laceration of the great vessels: the

great vessels of the mediastinum can be directly transected and case

reports have included the pulmonary artery,204 brachiocephalic vein,42 and superior vena cava.147 Compression of any of the great vessels without frank laceration can also occur as a complication of injury.140,144 -

Esophageal perforation/rupture: cases of esophageal rupture are often described in relation to local sequelae. Howard90 reported a case of rupture complicated by osteomyelitis of the clavicle. Wasylenko196 reported on a fatal tracheoesophageal fistula.

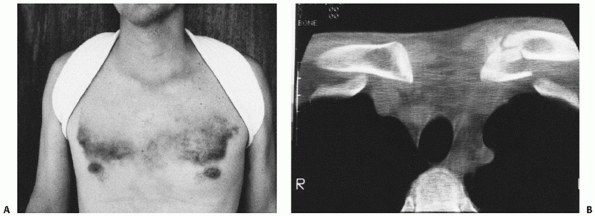

reported a bilateral traumatic dislocation of the SC joint. The senior

author has treated four cases of bilateral SC dislocation. Bilateral

subluxation has also been reported.77

reported a single case and reviewed 15 cases that had been previously

reported. With the exception of this patient, all patients had been

treated conservatively with acceptable function. Dieme et al.53 reported three cases of “floating clavicle.” In 1990, Sanders et al.170

reported 6 patients who had a dislocation of both ends of the clavicle.

Two patients who had fewer demands on the shoulder did well with only

minor symptoms after nonoperative management. The other 4 patients had

persistent symptoms that were localized to the acromioclavicular (AC)

joint. Each of these patients had a reconstruction of the AC joint,

which resulted in a painless, full range of motion and a return to

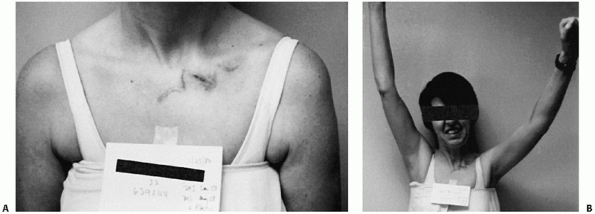

normal activity (Fig. 40-4). AC dislocation can also accompany medial clavicle epiphyseal fracture/dislocation.75 Wade et al.194

reported a trapped posterior inferior AC dislocation associated with a

medial epiphyseal fracture which required open reduction of the AC

joint and exploration of the SC injury with a good result.

anterior or posterior dislocation of the SC joint has been noted. It is

important to assess the AC joint and the SC joint in the face of the

more obvious midshaft clavicle fracture to avoid a delay in diagnosis.

Tanlin,183 Arenas et al.,4 Friedl and Fritz,70 and Thomas184 have all reported patients who had an anterior dislocation of the SC joint and a fracture of the midclavicle. Allen et al.,3 Nakazato,138 and Mounasamy136

each reported on a skeletally immature patient who had an ipsilateral

clavicle fracture and a posterior dislocation of the SC joint. Velutini

and Tarazona192 reported a bizarre

case of posterior dislocation of the left medial clavicle, the first

rib, and a section of the manubrium. Elliott58

reported on a tripartite injury about the clavicle region in which the

patient had an anterior subluxation of the right SC joint, a type II

injury to the right AC joint, and a fracture of the right midclavicle.

Pearsall and Russell149 reported a

patient who had an ipsilateral clavicle fracture, an anterior SC joint

subluxation, and a long thoracic nerve injury. All of these injuries

involving the SC joint and the clavicle were associated with severe

trauma to the shoulder region.

reported a patient with SC dislocation associated with scapulothoracic

dissociation. This patient had also sustained a transection of the

axillary artery and an avulsion of the median nerve. Following a

vascular repair and an above the elbow amputation, this patient was

left with a complete brachial plexopathy.

for treatment of each individual dislocation separately. When patients

have dislocations of both ends of the clavicle, we recommend

stabilization of the AC joint with appropriate surgical techniques for

type III, IV, V, and VI separations. The SC dislocation is generally

treated nonoperatively with the exception of the

unreduced

posterior dislocation which is treated following the guidelines

outlined later in this chapter. When the clavicle is fractured with an

SC dislocation, the clavicle should be stabilized with internal

fixation for posterior injuries and treated as appropriate for an

isolated clavicle fracture when the SC dislocation is anterior. In the

rare case of a scapulothoracic disassociation and SC dislocation, only

the exclusive criteria for SC management can be applied in isolation.

|

|

FIGURE 40-4 Dislocation of both ends of the clavicle. A. Clinical view demonstrating anterior dislocation of the right SC joint. B. The axillary radiograph reveals posterior dislocation of the AC joint. C. These injuries are generally treated by AC joint repair/reconstruction with return of near normal function.

|

initial treating physician to associated injuries and to the direction

of dislocation. The patient should be questioned about pain in the

adjacent ACjoint and glenohumeral joint. The patient with a posterior

dislocation has more pain than a patient with an anterior dislocation,

and the anterosuperior fullness of the chest produced by the clavicle

is less prominent and visible when compared with the normal side. The

usually palpable medial end of the clavicle is displaced posteriorly.

The corner of the sternum is easily palpated as compared with the

normal SC joint. Venous congestion may be present in the neck or in the

upper extremity.80 Symptoms may also include a dry irritating cough and hoarseness.59,150

Breathing difficulties, shortness of breath, or a choking sensation may

be noted. Circulation to the ipsilateral arm may be decreased, although

the presence of pulses does not exclude vessel injury. The patient may

complain of difficulty in swallowing or a tight feeling in the throat

or may be in a state of complete shock or possibly have a pneumothorax.

The distal neurologic exam may reveal diminished sensation or weakness

secondary to brachial plexus compression. Complete nerve deficits

suggest more severe injury patterns. The exam should include assessment

of the Wynne-Davies signs205 of

generalized ligamentous laxity as these patients are predisposed to

atraumatic anterior SC joint subluxation. We have seen a number of

patients who clinically appeared to have an anterior dislocation of the

SC joint but on x-ray studies were shown to have complete posterior

dislocation. The point is that

one

cannot always rely on the clinical findings of observing and palpating

the joint to make a distinction between anterior and posterior

dislocations.

|

|

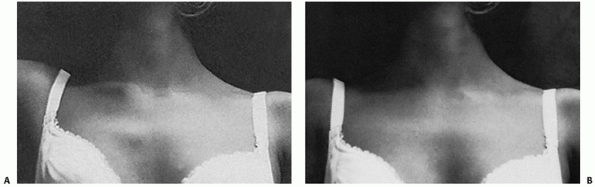

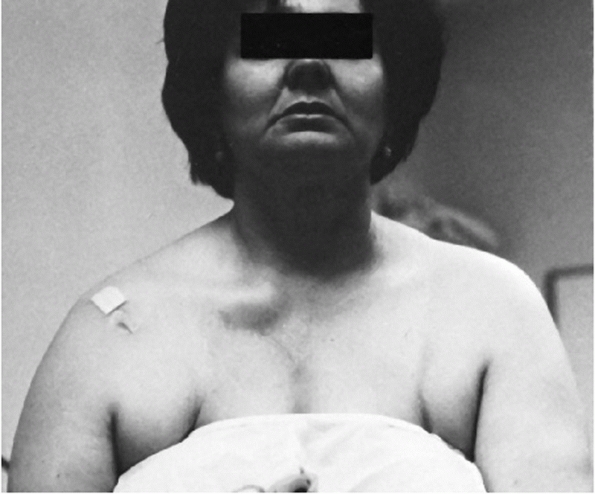

FIGURE 40-5 A.

A 34-year-old patient was involved in a motorcycle accident and sustained an anterior blow to the chest. Note the symmetric anterior chest wall ecchymosis. B. CT reveals a left medial clavicle fracture without disruption of the SC joint. |

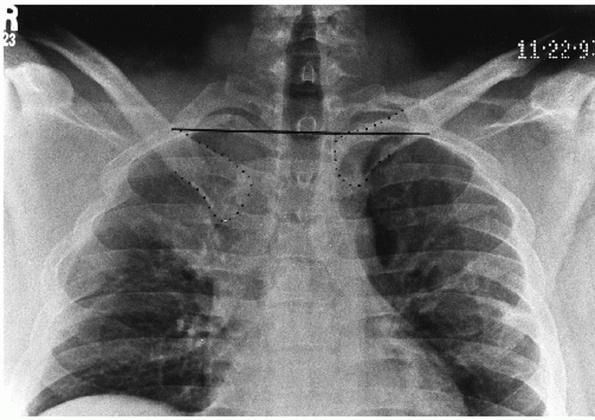

posteroanterior radiographs of the chest or SC joint suggest something

is wrong with one of the clavicles, because it appears to be displaced

as compared with the normal side. McCulloch et al.128

reported that on nonrotated frontal radiographs, a difference in the

relative craniocaudal positions of the medial clavicles of greater than

50% of the width of the heads of the clavicles suggests dislocation. It

would be ideal to take a view at right angles to the anteroposterior

plane, but because of the anatomy, it is impossible to obtain a true

90-degree cephalic-to-caudal lateral view. Lateral radiographs of the

chest are at right angles to the anteroposterior plane, but they cannot

be interpreted because of the density of the chest and the overlap of

the medial clavicles with the first rib and the sternum. Regardless of

a clinical impression that suggests an anterior or posterior

dislocation, radiographs and preferably a CT scan must be obtained to

confirm one’s suspicions (Fig. 40-5).

|

|

FIGURE 40-6 Heinig view. A. Positioning of the patient for x-ray evaluation of the SC joint, as described by Heinig. B. Heinig view demonstrating a normal relationship between the medial end of the clavicle (C) and the manubrium (M).

|

While the serendipity view is frequently obtained as a front line image

for evaluation of the SC joint, the Heinig and Hobbs views are rarely

obtained if CT is available. However, the Heinig and Hobbs views can be

useful when suspicion is high on clinical exam and confirmation is

needed before referral for CT, especially in the outpatient setting

when delayed presentation often leads to misdiagnosis.

x-ray tube is placed approximately 30 inches from the involved SC joint

and the central ray beam is directed tangential to the joint and

parallel to the opposite clavicle. The cassette is placed against the

opposite shoulder and centered on the manubrium (Fig. 40-6).

|

|

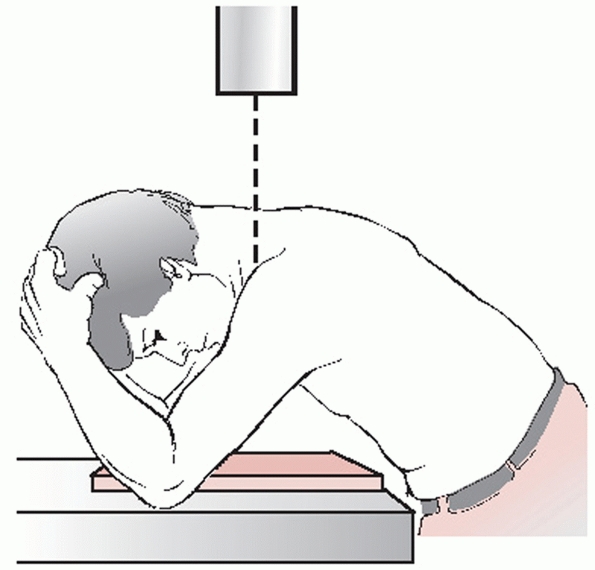

FIGURE 40-7

Hobbs view. Positioning of the patient for x-ray evaluation of the SC joint, as recommended by Hobbs. (From Hobbs DW. Sternoclavicular joint: a new axial radiographic view. Radiology 1968;90:801-802.) |

the x-ray table, high enough to lean forward over the table. The

cassette is placed on the table, and the lower anterior rib cage is

against the cassette (Fig. 40-7). The patient

leans forward so that the nape of his flexed neck is almost parallel to

the table. The flexed elbows straddle the cassette and support the head

and neck. The x-ray source is above the nape of the neck, and the beam

passes through the cervical spine to project the sternoclavicular

joints onto the cassette.

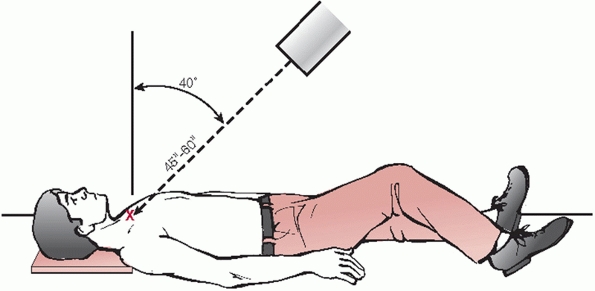

named because that is the way it was developed. The senior author

accidentally noted that the next best thing to having a true

cephalocaudal lateral view of the SC joint was a 40-degree cephalic

tilt view. The patient is positioned on his back squarely and in the

center of the x-ray table. The tube is tilted at a 40-degree angle off

the vertical and is centered directly on the sternum (Figs. 40-8, 40-9, 40-10 and 40-11).

A nongrid 11- × 14-inch cassette is placed squarely on the table and

under the patient’s upper shoulders and neck so that the beam aimed at

the sternum will project both clavicles onto the film.

|

|

FIGURE 40-8

Serendipity view. Positioning of the patient to take the “serendipity” view of the SC joints. The x-ray tube is tilted 40 degrees from the vertical position and aimed directly at the manubrium. The nongrid cassette should be large enough to receive the projected images of the medial halves of both clavicles. In children, the tube distance from the patient should be 45 inches; in thicker-chested adults, the distance should be 60 inches. |

|

|

FIGURE 40-9 When viewed from around the level of the patient’s knees, it is apparent that the left clavicle is dislocated anteriorly.

|

|

|

FIGURE 40-10

Posterior dislocation of the right medial clavicle as seen on 40-degree cephalic tilt serendipity radiograph. The right clavicle is inferiorly displaced as compared to the normal left clavicle. |

|

|

FIGURE 40-11 Interpretation of the cephalic tilt (serendipity view) x-ray films of the SC joints. A. In the normal person, both clavicles appear on the same imaginary line drawn horizontally across the film. B.

In a patient with an anterior dislocation of the right SC joint, the medial half of the right clavicle is projected above the imaginary line drawn through the level of the normal left clavicle. C. If the patient has a posterior dislocation of the right SC joint, the medial half of the right clavicle is displaced below the imaginary line drawn through the normal left clavicle. |

|

|

FIGURE 40-12 A. Routine anteroposterior radiograph of posteriorly dislocated right SC joint. B.

The anteroposterior view is suggestive of a posterior dislocation. However, the CT scan clearly demonstrates the posteriorly displaced right medial clavicle. Note the displacement of the trachea. |

distinguishing between a SC dislocation and a fracture of the medial

clavicle. They are also helpful in questionable anterior and posterior

injuries of the SC joint to distinguish fractures from dislocations and

to evaluate arthritic changes.

recommended the use of tomography and said it was far more valuable

than routine radiographs and the fingertips of the examining physician.

In 1975, Morag and Shahin135

reported on the value of tomography, which they used in a series of 20

patients, and recommended that it be used routinely to evaluate

problems of the SC joint. From a study of normal SC joints, they

pointed out the variation in the x-ray appearance in different age

groups.

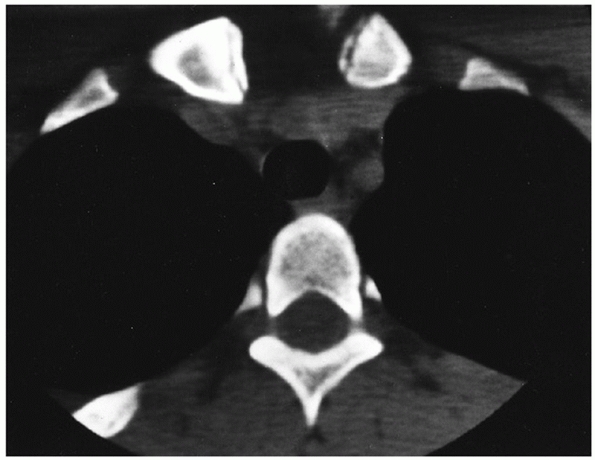

It clearly distinguishes injuries of the joint from fractures of the

medial clavicle and defines minor subluxations of the joint. One must

remember to request CT scans of both SC joints and the medial half of both clavicles

so the injured side can be compared with the normal side. Numerous

authors have reported on the value of using a CT scan as the method of

choice for radiographic evaluation of the SC joint.30,43,44,51,52,54,111,114,120 Lucet et al.120

used CT scans to evaluate the SC joints in 60 healthy subjects

homogeneously distributed by sex and decade of life from 20 to 80 years

old. They reported that 98% of the subjects had at least one sign of

various abnormalities, such as sclerosis, osteophytes, erosion, cysts,

and joint narrowing. The number of signs increased with age and the

number of clavicular signs was greater than those in the sternum.

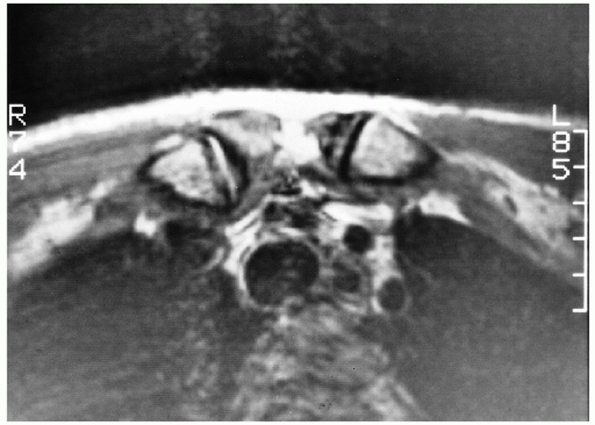

correlated magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans with anatomic

sections in 14 SC joints from elderly cadavers. They concluded that MRI

did depict the anatomy of the SC joint and surrounding soft tissues (Fig. 40-13).

T2-weighted images were superior to T1-weighted images in depicting the

intra-articular disk. Magnetic resonance arthrography allowed the

delineation of perforations in the intra-articular disk. In children

and young adults when there are questions of diagnosis between

dislocation and

SC

joint or physeal injury, the MRI scan can be used to determine if the

epiphysis has displaced with the clavicle or is still adjacent to the

manubrium. Benitez et al.15

evaluated 41 patients with SC trauma at an average of 9 months

postinjury and found an 80% incidence of articular disk injury and a

59% incidence of subluxation. MRI may be useful in this light to better

understand the in vivo mechanisms of injury of the SC joint and to

elucidate causes of pain well after the traumatic event.16

|

|

FIGURE 40-13 MRI of the SC joint. The epiphysis on both medial clavicles is clearly visible.

|

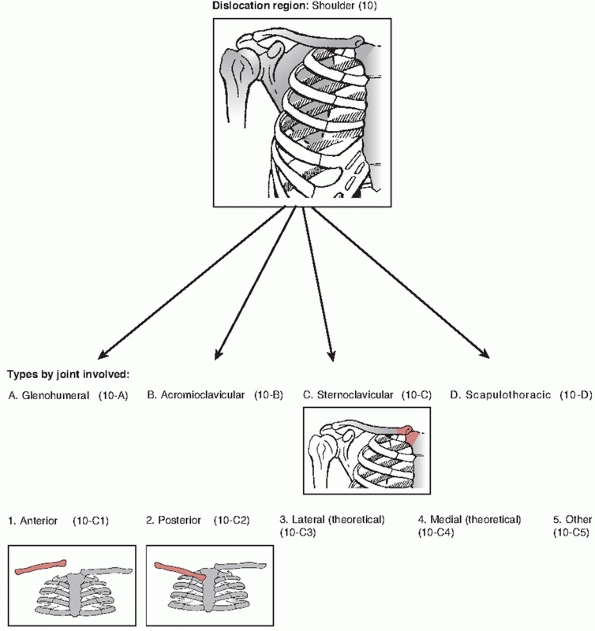

subluxations and dislocations: the anatomic position of the injury and

the etiology of the problem. The Orthopaedic Trauma Association

Classification is simply based on the direction of the dislocation and

not on etiology.

described. A recent case report confirms the possibility of a superior

dislocation which occurred after and indirect force mechanism. The

authors noted that only the interclavicular and intra-articular disc

ligaments were ruptured (Fig. 40-14).115

dislocations are the most common. The medial end of the clavicle is

displaced anteriorly or anterosuperiorly to the anterior margin of the

sternum.

uncommon. The medial end of the clavicle is displaced posteriorly or

posterosuperiorly with respect to the posterior margin of the sternum

(see Fig. 40-19A,B).

sprain, all the ligaments are intact and the joint is stable. There may

be local damage to the capsule and the joint may develop an effusion,

but there is no translation of the clavicle or loss of congruity.

In a moderate sprain, there is subluxation of the SC joint. The

capsular ligaments, the intra-articular disk, and costoclavicular

ligaments may be partially disrupted. The subluxation is usually

anterior but posterior subluxation can occur.

dislocated SC joint, the capsular and intra-articular ligaments are

ruptured. Occasionally, the costoclavicular ligament is intact but

stretched out enough to allow dislocation of the joint.

the initial acute traumatic dislocation does not heal, mild to moderate

forces may produce recurrent dislocations; this is rare.

original dislocation may go unrecognized, it may be irreducible, or the

physician may decide not to reduce certain dislocations.

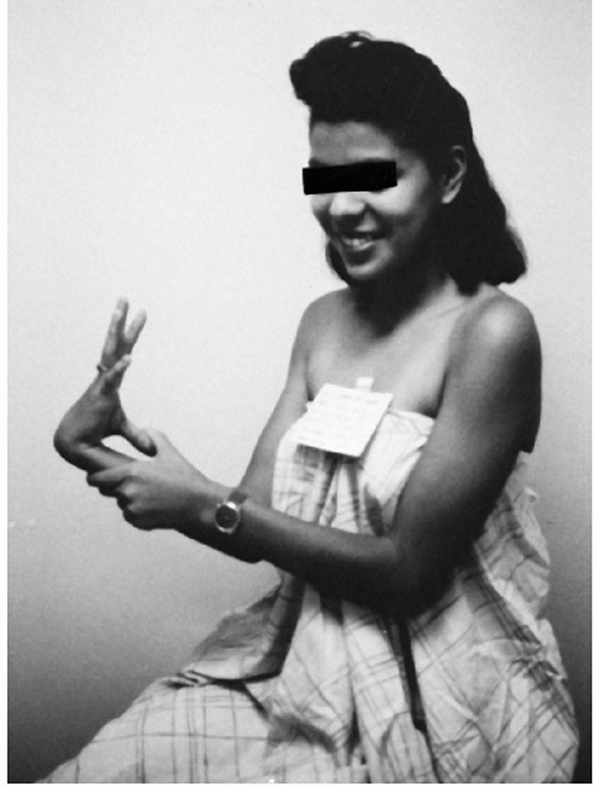

It usually occurs in patients who have generalized ligament laxity of

other joints. In middle-aged women, spontaneous anterior or

anterior/superior subluxation can occur and may be in association with

condensing osteitis of the clavicle.191

In some patients, the atraumatic anterior dislocation of the SC joint

is painful and is associated with a snap or pop as the arm is elevated

overhead, and another snap occurs when the arm is returned to the

patient’s side. Atraumatic posterior dislocation126 and subluxation have been reported.127

important to consider other pathologies particular to the SC joint

during the diagnostic process. Infection may mimic trauma and should

especially be considered in patients with history of intravenous drug

abuse, immunocompromise, or indwelling subclavian catheters. SC

hyperostosis is an inflammatory condition of the SC joint and medial

ribs which results in new bone formation and even ankylosis of the SC

joint. It is associated with Japanese ethnicity and dermatologic

lesions in the palms and plantar regions. Three conditions which

predominate in women are condensing osteitis, Friedreich disease, and

osteoarthritis.201 Condensing

osteitis of the medial clavicle typically occurs in women of late

child-bearing age and presents as a painful joint with sclerosis on

radiographs, similar to condensing osteitis of the ilium and pubis seen

in the same demographic group. Friedreich’s disease is osteonecrosis of

the medial clavicle. Osteoarthritis typically manifests in the

postmenopausal years and can appear as a pseudosubluxation anteriorly.23

|

|

FIGURE 40-14

Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification of SC injuries. (From Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, et al. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium-2007: Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification, database, and outcomes committee. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10 Suppl):S104-107, with permission.) |

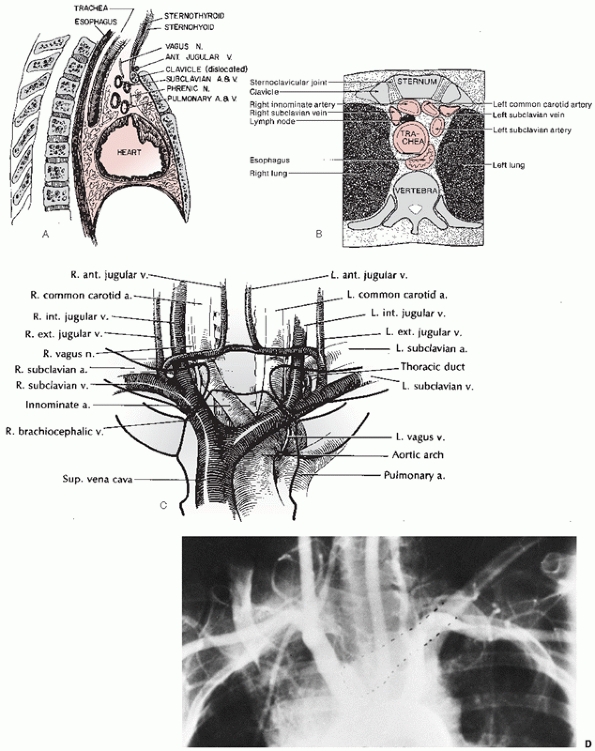

near the SC joint should be completely knowledgeable about the vast

array of anatomic structures immediately posterior to the SC joint.

There is a “curtain” of muscles (the sternohyoid, sternothyroid, and

scaleni) posterior to the SC joint and the inner third of the clavicle,

and this curtain blocks the view of the vital structures. Some of these

vital structures include the innominate artery, innominate vein, vagus

nerve, phrenic nerve, internal jugular vein, trachea, and esophagus (Fig. 40-16).

It is important to remember that the arch of the aorta, the superior

vena cava, and the right pulmonary artery are also very close to the SC

joint. Another structure to be aware of is the anterior jugular vein,

which is between the clavicle and the curtain of muscles.

true articulation between the upper extremity and the axial skeleton.

The articular surface of the clavicle is much larger than that of the

sternum, and both are covered with hyaline cartilage. The enlarged

bulbous medial end of the clavicle is concave front to back and convex

vertically and therefore creates a saddle-type joint with the

clavicular notch of the sternum.81,164 The clavicular notch of the sternum is curved, and the joint surfaces are not congruent. Cave37 demonstrated that in 2.5% of patients,

there is a small facet on the inferior aspect of the medial clavicle,

which articulates with the superior aspect of the first rib at its

synchondral junction with the sternum.

|

|

FIGURE 40-15 Spontaneous anterior subluxation of the SC joint. A.

With the arm in the overhead position, the medial end of the right clavicle spontaneously subluxates anteriorly without any trauma. B. When the arm is brought back down to the side, the medial end of the clavicle spontaneously reduces. Usually this is not associated with significant discomfort. (From Rockwood CA, Matsen F III, eds. The Shoulder. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1990, with permission.) |

articulates with the upper angle of the sternum, the SC joint has the

distinction of having the least amount of bony stability of the major

joints of the body.

the SC joint has to come from its surrounding ligaments: the

intra-articular disk ligament, the extra-articular costoclavicular

ligament (rhomboid ligament), the capsular ligament, and the

interclavicular ligament.

ligament is a very dense, fibrous structure that arises from the

synchondral junction of the first rib and the sternum and passes

through the SC joint. It divides the joint into two separate spaces.81,164 The upper attachment is on the superior and posterior aspects of the medial clavicle. DePalma48

has shown that the disk is perforated only rarely; the perforation

allows a free communication between the two joint compartments.

Anteriorly and posteriorly, the disk blends into the fibers of the

capsular ligament. The disk acts as a checkrein against medial

displacement of the inner clavicle.

also called the rhomboid ligament, is short and strong and consists of

an anterior and a posterior fasciculus.14,36,81 Cave36 reported that the average length is 1.3 cm, the maximum width is 1.9 cm, and the average thickness is 1.3 cm. Bearn14

has shown that there is always a bursa between the two components of

the ligament. Because of the two different parts of the ligament, it

has a twisted appearance.81 The

costoclavicular ligament attaches below to the upper surface of the

first rib and at the adjacent part of its synchondral junction with the

sternum. It attaches above to the margins of the impression on the

inferior surface of the medial end of the clavicle, sometimes known as

the rhomboid fossa.81,164 Cave36

has shown, in a study of 153 clavicles, that the attachment point of

the costoclavicular ligament to the clavicle can be one of three types:

(i) a depression, the rhomboid fossa (30%), (ii) flat (60%), or (iii)

an elevation (10%).

anteromedial surface of the first rib and are directed upward and

laterally. The fibers of the posterior fasciculus are shorter and rise

lateral to the anterior fibers on the rib and are directed upward and

medially. The fibers of the anterior and posterior components cross and

allow for stability of the joint during rotation and elevation of the

clavicle. The two-part costoclavicular ligament is in many ways similar

to the two-part configuration of the coracoclavicular ligament on the

outer end of the clavicle.

experimentally that the anterior fibers resist excessive upward

rotation of the clavicle and that the posterior fibers resist excessive

downward rotation. Specifically, the anterior fibers also resist

lateral displacement, and the posterior fibers resist medial

displacement.

connects the superomedial aspects of each clavicle with the capsular

ligaments and the upper sternum. According to Grant,79

this band may be comparable to the wishbone of birds. This ligament

helps the capsular ligaments to produce “shoulder poise,” that is, to

hold up the shoulder. This can be tested by putting a finger in the

superior sternal notch; with elevation of the arm, the ligament is

quite lax, but as soon as both arms hang at the sides, the ligament

becomes tight.

have shown experimentally that the costoclavicular and interclavicular

ligaments have little effect on anterior or posterior translation of

the SC joint. In an anatomic study, Tubbs et al.189

found that the interclavicular ligament prevented superior displacement

of the clavicle with shoulder adduction and depression and failure

occurred at 53.7N.

anterosuperior and posterior aspects of the joint and represents

thickenings of the joint capsule. The anterior portion of the capsular

ligament is heavier and stronger than the posterior portion.

|

|

FIGURE 40-16 Applied anatomy of the vital structures posterior to the SC joint. Sagittal (A) and transverse (B) views in cross section demonstrating the structures posterior to the SC joint. C. A diagram demonstrating the close proximity of the major vessels posterior to the SC joint. D. An aortogram showing the relationship of the medial end of the clavicle to the major vessels in the mediastinum.

|

this may be the strongest ligament of the SC joint, and it is the first

line of defense against the upward displacement of the inner clavicle

caused by a downward force on its distal end. The clavicular attachment

of the ligament is primarily onto the epiphysis of the medial clavicle,

with some secondary blending of the fibers into the metaphysis. The

senior author has demonstrated this, as have Poland,152 Denham and Dingley,47 and Brooks and Henning.25

Although some authors report that the intra-articular disk ligament

greatly assists the costoclavicular ligament in preventing upward

displacement of the medial clavicle, Bearn14

has shown that the capsular ligament is the most important structure in

preventing upward displacement of the medial clavicle. In experimental

postmortem studies, he determined, after

cutting

the costoclavicular, intra-articular disk, and interclavicular

ligaments, that they had no effect on clavicle poise. However, the

division of the capsular ligament alone resulted in a downward

depression on the distal end of the clavicle. Bearn’s14 findings have many clinical implications for the mechanisms of injury of the SC joint.

|

|

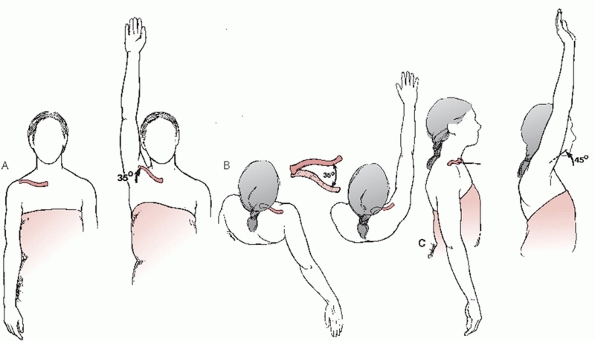

FIGURE 40-17 Motions of the clavicle at the SC joint. A. With full overhead elevation, the clavicle elevates 35 degrees. B. With adduction and extension, the clavicle displaces anteriorly and posteriorly 35 degrees. C. The clavicle rotates on its long axis 45 degrees, as the arm is elevated to the full overhead position.

|

measured anterior and posterior translation of the SC joint. Anterior

and posterior translation were measured in intact specimens and

following transection of randomly chosen ligaments about the SC joint.

Cutting the posterior capsule resulted in significant increases in

anterior and posterior translation. Cutting the anterior capsule

produced significant increases in anterior translation. This study

demonstrated that the posterior SC joint capsule is the most important

structure for preventing both anterior and posterior translation of the

SC joint, with the anterior capsule acting as an important secondary

stabilizer.

studied the function of the subclavius muscle and found that the basic

function of the subclavius was to stabilize the SC joint. They also

stated that the subclavius could act as a substitute for the ligaments

of the SC joint. We believe that this is an important study as it might

explain why some people, after loss of the medial clavicle and the SC

ligament, do not have instability of the medial end of the clavicle. It

also gives a reason for leaving the subclavius muscle intact during

operations on the SC joint.

a ball-and-socket joint with motion in almost all planes, including

rotation.19,119

In normal shoulder motion the clavicle, via motion through the SC

joint, is capable of 30 to 35 degrees of upward elevation, 35 degrees

of combined forward and backward movement, and 45 to 50 degrees of

rotation around its long axis (Fig. 40-17). It

is likely the most frequently moved joint of the long bones in the

body, because almost any motion of the upper extremity is transferred

proximally to the SC joint.

to ossify (during the fifth intrauterine week), the epiphysis at the

medial end of the clavicle is the last of the long bones in the body to

appear and the last physis to close (Fig. 40-18). The medial clavicular epiphysis does not ossify until the 18th to 20th year,

and it fuses with the shaft of the clavicle around the 23rd to 25th year.79,81,152 Webb and Suchey,198

in an extensive study of the physis of the medial clavicle in 605 males

and 254 females at autopsy, reported that complete union may not be

present until 31 years of age. This knowledge of the epiphysis is

important, because many of the SC dislocations in adults are injuries

through the physeal plate.

|

|

FIGURE 40-18 CT scan demonstrating the thin, wafer-like disk of the epiphysis of the medial clavicle.

|

successfully managed by nonoperative measures (observation or closed

reduction). This includes most of the acute and chronic anterior

subluxations and dislocations, the acute traumatic posterior

subluxations and dislocations, and, remembering that the physis of the

medial clavicle does not close until the 23rd to 25th year, the acute

traumatic anterior and posterior physeal injuries of the medial

clavicle.

irreducible posterior dislocation that may require a surgical

procedure. Some authors also recommend the open reduction and internal

fixation of acute and chronic anterior dislocations.

Application of ice is recommended for the first 12 hours, followed by

heat for the next 24 to 48 hours. The joint may be subluxated

anteriorly or posteriorly, which may be reduced by drawing the

shoulders backward as if reducing and holding a fracture of the

clavicle. For both anterior and posterior subluxations that are stable,

a clavicle strap can be used to hold the reduction. A sling and swath

can also be used to hold up the shoulder and to prevent motion of the

arm. The patient should be protected from further injury for 4 to 6

weeks. Immobilization can be accomplished with a soft figure-of-eight

bandage with a sling for temporary support.

of acute anterior dislocation of the SC joint. A large series of SC

injuries was published in 1988 by Fery and Sommelet.67

They reported on 40 anterior dislocations, 8 posterior dislocations,

and 1 unstable SC joint. They ended up treating 15 injuries closed, but

because of problems, had to operate on 17 patients; 17 patients were

not treated. They had good and excellent results with both the closed

and operative treatment, but recommended that closed reduction should

be initially undertaken. In 1990, de Jong and Sukul46

reported long-term follow-up results in 10 patients with traumatic

anterior SC dislocations. All patients were treated nonoperatively with

analgesics and immobilization. The results of treatment were good in 7

patients, fair in 2 patients, and poor in 1 patient at an average

follow-up of 5 years. Most acute anterior dislocations are unstable

following reduction, and many operative procedures have been described

to repair or reconstruct the joint. At this time, the mixed results of

these procedures have not clearly advanced a case for their use instead

of observation.

dislocation of the SC joint may be accomplished with local or general

anesthesia or, in stoic patients, without anesthesia. Most authors

recommend the use of narcotics or muscle relaxants. The patient is

placed supine on the table, lying on a 3- to 4-inch-thick pad placed

between the shoulders. In this position, the joint may reduce with

direct gentle pressure over the anteriorly displaced clavicle. However,

when the pressure is released, the clavicle usually dislocates again.

Occasionally, the clavicle will remain reduced. Sometimes, the

physician will need to push both of the patient’s shoulders back to the

table while an assistant applies pressure to the anteriorly displaced

clavicle.

healing, the shoulders should be held back for 4 to 6 weeks with a

figure-of-eight dressing or one of the commercially available

figure-of-eight straps used to treat fractures of the clavicle.

of anterior dislocations of the SC joint, we believe that the operative

complications are too great and the end results are too unsatisfactory

to consider an open procedure.

patient complains of moderate discomfort. The joint may be swollen and

tender to palpation. Care must be taken to rule out the more

significant posterior dislocation, which may have initially occurred

and spontaneously reduced. When in doubt, it is best to protect the SC

joint with a figure-of-eight bandage for 2 to 6 weeks. As with all

injuries to the SC joint, it must be carefully evaluated by CT scan.

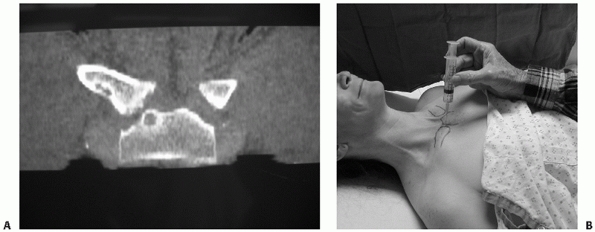

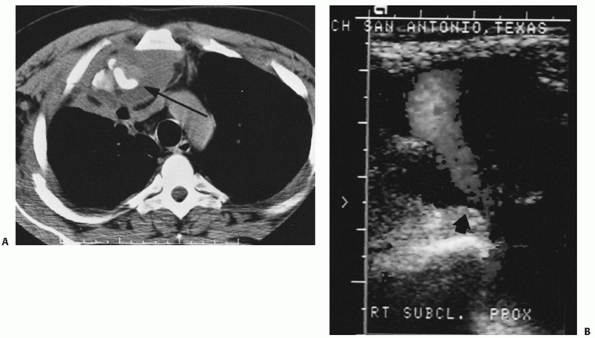

the SC joint is suspected, the physician must perform a very careful

examination of the patient to rule out damage to the structures

posterior to the joint such as the trachea, esophagus, the brachial

plexus, the great vessels, and the lungs. Not only is a careful

physical examination important, but special radiographs must be

obtained. A CT scan of both medial clavicles allows the physician to

compare the injured side with the normal side, and this is the

recommended imaging study. Occasionally, when vascular injuries are

suspected, the CT scan will need to be combined with an arteriogram of

the great vessels.

whom many if not most of the injuries are physeal fractures, a

nonoperative approach of closed reduction should be strongly considered.

a posterior dislocation of the SC joint because the patient has pain

and muscle spasms. However, for the stoic patient, some authors have

performed the reduction under intravenous narcotics and muscle

relaxants.

that the treatment of choice for posterior SC dislocation was

operative. However, since the 1950s, the treatment of choice has been

closed reduction.33,40,44,65,83,86,129,130,134,148,169,181

dislocations are successfully reduced closed if accomplished within 48

hours of injury. A variety of techniques have been described.

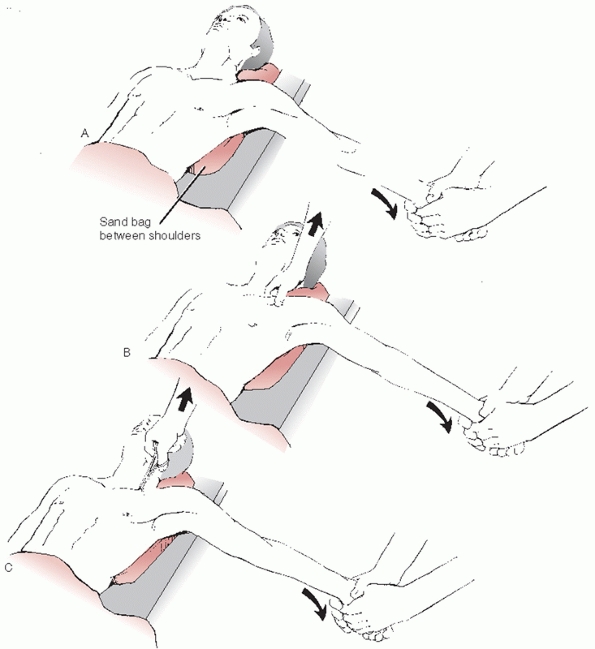

the patient is placed on his or her back with the dislocated shoulder

near the edge of the table. A 3- to 4-inch-thick sandbag is placed

between the shoulders (Fig. 40-19). Lateral

traction is applied to the abducted arm, which is then gradually

brought back into extension. This may be all that is necessary to

accomplish the reduction. The clavicle usually reduces with an audible

snap or pop, and it is almost always stable. Too much extension can

bind the anterior surface of the dislocated medial clavicle on the back

of the manubrium. Occasionally, it may be necessary to grasp the medial

clavicle with one’s fingers to dislodge it from behind the sternum. If

this fails, the skin is prepared, and a sterile towel clip is used to

grasp the medial clavicle to apply lateral and anterior traction (Fig. 40-20).

|

|

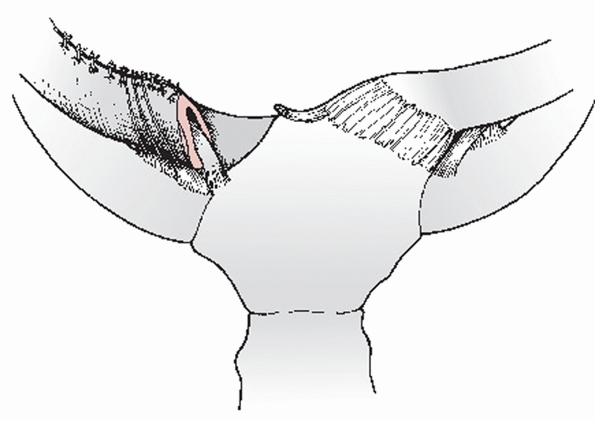

FIGURE 40-19 Technique for closed reduction of the SC joint. A.

The patient is positioned supine with a sandbag placed between the two shoulders. Traction is then applied to the arm against countertraction in an abducted and slightly extended position. In anterior dislocations, direct pressure over the medial end of the clavicle may reduce the joint. B. In addition to the traction, it may be necessary to manipulate the medial end of the clavicle with the fingers to dislodge the clavicle from behind the manubrium. C. In stubborn posterior dislocations, it may be necessary to sterilely prepare the medial end of the clavicle and use a towel clip to grasp around the medial clavicle to lift it back into position. |

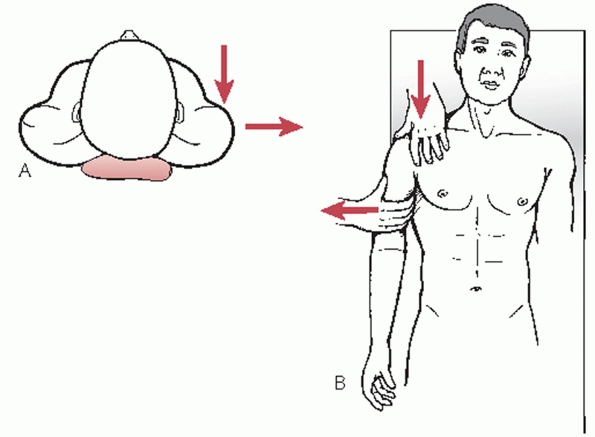

the patient is supine on the table with a 3- to 4-inch bolster between

the shoulders. Traction is then applied to the arm in adduction, while

a downward pressure is exerted on the shoulder (Fig. 40-21). The clavicle is levered over the first rib into its normal position. Buckerfield and Castle29 reported that this technique was successful in 7 patients when the abduction traction technique had failed.

|

|

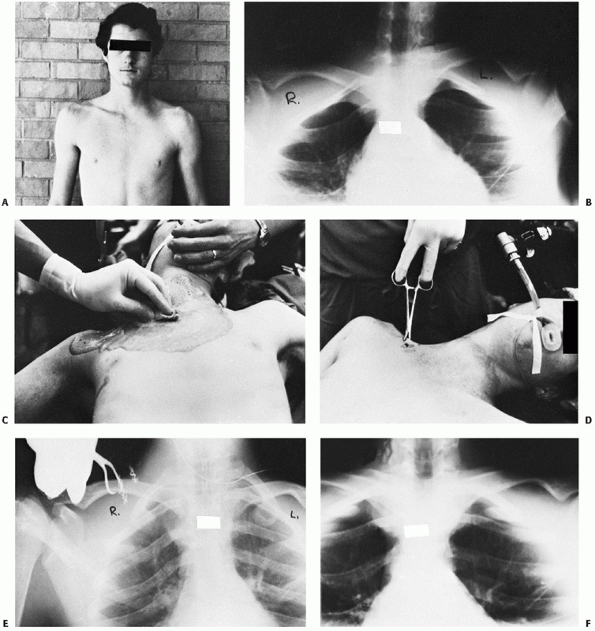

FIGURE 40-20 Posterior dislocation of the right SC joint. A.

A 16-year-old boy has a 48-hour-old posterior dislocation of the right medial clavicle that occurred from a direct blow to the anterior right clavicle. He noted immediate onset of difficulty in swallowing and some hoarseness in his voice. B. A 40-degree cephalic tilt radiograph confirmed the posterior displacement of the right medial clavicle as compared with the left clavicle. Because of the patient’s age, this was considered most likely to be a physeal injury of the right medial clavicle. C. Because the injury was 48 hours old, we were unable to reduce the dislocation with simple traction on the arm. The right shoulder was surgically cleansed so that a sterile towel clip could be used. D. With the towel clip placed securely around the clavicle and with continued lateral traction, a visible and audible reduction occurred. E. Postreduction radiographs showed that the medial clavicle had been restored to its normal position. The reduction was quite stable, and the patient’s shoulders were held back with a figure-of-eight strap. F. The right clavicle has remained reduced. Note the periosteal new bone formation along the superior and inferior borders of the right clavicle. This is the result of a physeal injury, whereby the epiphysis remains adjacent to the manubrium while the clavicle is displaced out of a split in the periosteal tube. |

|

|

FIGURE 40-21 The Buckerfield-Castle technique. A,B.

The patient is lying on the table with a bolster between the shoulders. Traction is applied to the arm in adduction while a downward force is applied on the shoulder. |

healing, the shoulders should be held back for 4 to 6 weeks with a

figure-of-eight dressing or one of the commercially available

figure-of-eight straps used to treat fractures of the clavicle.

maintaining stability of the posterior dislocation of the SC joint. A

delay in reduction of 48 hours may make closed reduction impossible,

reinforcing the importance of early diagnosis.35

In these situations, open reduction and acute repair of the soft

tissues is warranted. The first option is direct repair of the anterior

and posterior capsule, intra-articular disk ligament, and

costoclavicular ligament. The surgeon can also employ one of the

various techniques that are available for ligament reconstruction for

an unreduced or chronic dislocation, especially if additional stability

is required due to the disruption of native tissues.

reconstructed, but do not generally require such procedures.

Occasionally, following conservative treatment of a subluxation of the

SC joint, the pain lingers on and the symptoms of popping and grating

persist. Joint exploration may be required as several authors have

reported symptom relief following joint exploration, removal of the

torn or degenerated intra-articular disk, along with a capsulorraphy.6,12,55

Many authors have included chronic or unreduced anterior dislocations

with posterior dislocations in their series of operative patients. This

makes it difficult to understand the true benefits of surgery in this

situation. Postoperatively, recurrent instability,67 limitations of activity,7 and pain61

often occur, and patient expectations should be adjusted accordingly.

While most chronic posterior SC fracture-dislocations require open

procedures, a singular exception is young adults who may have no

symptoms, and the physician can wait to see if the physeal plate

remodeling process removes the posteriorly displaced bone.163

displacement of the medial clavicle in the adult, an operative

procedure should be performed, because most adult patients cannot

tolerate posterior displacement of the clavicle into the mediastinum.

Complications accompanying unreduced posterior dislocations include

late thoracic outlet syndrome, late and significant vascular problems,

respiratory compromise, and dyspnea on exertion.24,73,117,186

We have treated patients with a medial clavicle resection and

reconstruction who have had complaints of swelling and arm

discoloration, in addition to signs and symptoms of effort thrombosis

and dysphagia secondary to a posteriorly displaced medial clavicle.

from the pressure of the posteriorly displaced clavicle into the

mediastinum and closed reduction is unsuccessful, an operative

procedure should be performed. If the patient is under 25 and without

symptoms after the initial obligatory attempt at closed reduction, then

close observation is acceptable as remodeling potential still exists.

Much like the AC joint, the recent literature has focused on case

reports of technique descriptions and modifications of existing

surgeries. Given the rarity of the injury and even rarer necessity for

surgery, there is no large experience with any of the techniques.

Nonetheless, certain basic principles should be adhered to in the midst

of this creative atmosphere.

that disturbs as few of the anterior ligament structures as possible.

If the procedure can be performed with the anterior ligaments intact,

then, with the shoulders held back in a figure-of-eight dressing, the

reduction may be stable. If all the ligaments are disrupted, a decision

has to be made whether to try to stabilize the SC joint or to resect

the medial 1 to 1.5 inches of the medial clavicle and anatomically

stabilize the remaining clavicle to the first rib. Resection alone

cannot be performed in the setting of disrupted ligaments and may

worsen the instability of the residual medial clavicle, requiring even

greater attention to the need for ligament reconstruction in such a

scenario.17

has to embrace a surgical strategy from the existing armamentarium.

Procedures can be viewed from two different perspectives: tissue and

stabilization. With regards to tissue, options are: (a) local ligaments

and capsule, (b) tendon transfers (subclavius or sternocleidomastoid),

or (c) grafts. With regards to stabilization, options are: (a)

stabilize to first rib, (b) stabilize to manubrium, or (c) stabilize to

the first rib and the manubrium. Fixation is generally provided by soft

tissue tensioning and suture, although augmenting with pins, plates, or

screws have all been proposed.

(i) intramedullary ligament transfer, (ii) costoclavicular ligament

reconstruction, and (iii) SC ligament reconstruction. Spencer and Kuhn,179

through a biomechanic analysis, evaluated the three different

reconstruction techniques in a cadaver model. The intramedullary

ligament,164 the

subclavius tendon transfer,32

and a semitendinosus graft placed in a figure-of-eight fashion through

drill-holes in the clavicle and manubrium were used to reconstruct the

SC joint. Each of the three reconstruction methods was subjected to

anterior or posterior translation to failure, and the changes in

stiffness compared with the intact state were analyzed statistically.

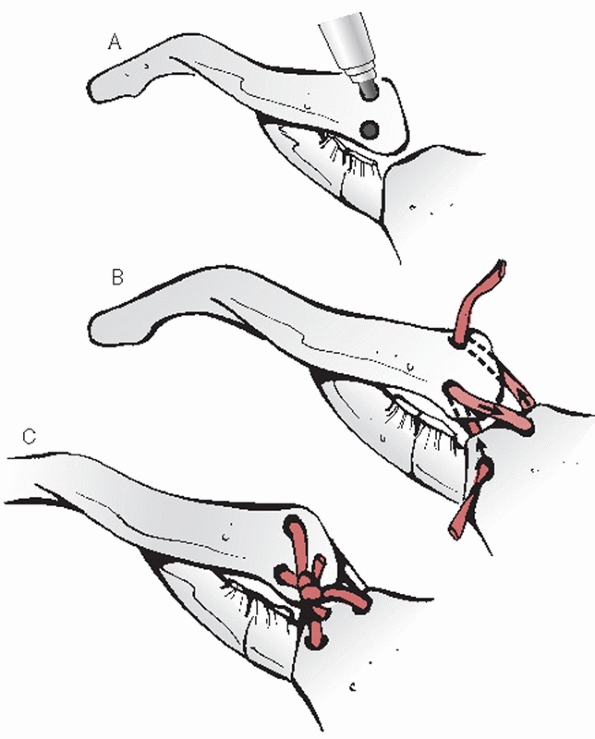

The figure-of-eight semitendinosus reconstruction showed superior

initial mechanical properties to the other two techniques. The authors

believed that this method reconstructs both the anterior and posterior

joint capsules providing an initial stiffness that is closer to that of

the intact sternoclavicular joint (Figs. 40-22 and 40-23). This technique has now been described with some success in young adults with refractory anterior instability.7,34,157

A plethora of other techniques abound in the literature. Some of the

literature from the 1960s and 1970s recommended stabilization of the SC

joint with Kirschner wires (K-wires) or Steinmann pins.25,28,47,49,59

These techniques have become largely historical due to their high

complication rate as will be discussed later. Other authors recommended

the use of various types of suture wires across the joint,9,31,70,84,98,142,151,156,181,182 reconstruction using local tendons,10,19,122,124 or the use of a special plate.85

Fascia lata, suture, screw fixation across the joint, subclavius

tendons, osteotomy of the medial clavicle, and resection of the medial

end of the clavicle have also been advocated.2,9,10,27,32,81,102,118,122,133,143,164,177

|

TABLE 40-1 Surgical Techniques for Sternoclavicular Reconstruction

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

used the clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid as an anterior

sling across the SC joint augmented with pins. Armstrong et al.5

modified the use of the sternocleidomastoid by using only a slip of the

sternal head and passing it through a medial clavicle bone tunnel. The

graft is sutured to itself to recreate the anterior SC ligament without exposure of the first rib.

|

|

FIGURE 40-22 Semitendinosus figure-of-eight reconstruction. A. Drill holes are passed from anterior to posterior through the medial part of the clavicle and the manubrium. B.

A free semitendinosus tendon graft is woven through the drill holes such that the tendon strands are parallel to each other posterior to the joint and cross each other anterior to the joint. C. The tendon ends are tied in a square knot and secured with suture. (From Spencer EE, Kuhn JE. Biomechanical analysis of reconstructions for sternoclavicular joint instability. J Bone Joint Surg 2004;86A(1):98-105.) |

|

|

FIGURE 40-23 Semitendinous figure-of-eight reconstruction A. Reduction of the SC joint. B. Passing the tendon graft through bone tunnels with suture passer. C. Tensioning of the graft. D. Completed figure-of-eight construct. (Courtesy of Charles E. Rosipal, MD, and T. Kevin O’Malley, MD.)

|

reported a safe surgical technique for stabilization of the SC joint

with the use of suture material. Their technique involved tying the

suture material on the superficial aspects of the medial clavicle and

manubrium. This avoids the exposure of the first rib and avoids

drilling through the inner cortex of the clavicle and manubrium.

Recently Abiddin1 has described a

similar technique with the use of suture anchors in the manubrium and

drill holes in the clavicle. While smooth pin and wire fixation is now

taboo, fixation of the SC joint with other metal implants is still

considered a valid option, although the implants do require removal.

Franck et al.69 reported an

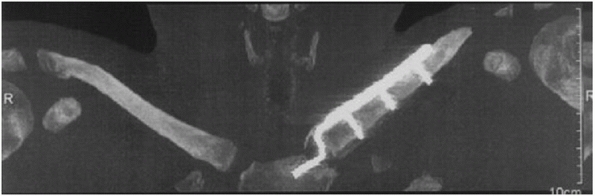

alternative therapy for traumatic SC instability using a plate for

stabilization. A Balser plate was contoured to match the shape of the

clavicle and the hook of the plate was used for sternal fixation. A

retrosternal hook position was used for seven anterior dislocations and

an intrasternal position was used for three posterior dislocations. For

each patient, the plate was attached to the clavicle with screws and

the torn ligaments were repaired. All plates were removed by 3 months.

At 1-year follow-up, 9 of 10 patients had excellent results with no

cases of redislocation. One patient developed a postoperative seroma

that required surgical drainage, and one patient developed arthrosis (Fig 40-24). In 1997, Brinker et al.24

described another technique of hardware fixation across the joint. The

authors used two 75-mm cannulated screws to stabilize an unstable

posterior dislocation of the SC joint. The screws were removed at 3

months, and at 10 months the patient had full range of motion without

pain and returned to college level football.

presented three cases of an Achilles tendon allograft and bone plug

used to treat anterior instability in 2 patients and a medial clavicle

fracture nonunion in one. The graft was fixed to a trough in the medial

clavicle resection with screws, passed through bone tunnels in the

manubrium and sutured upon itself.23 Meis et al.132

reported using an intramedullary transfer of the sternocleidomastoid as

an interposition for degenerative SC joint pain after resection.

reduction and internal fixation for acute injuries, as well as for

chronic problems. In 1982, Pfister and associates150,151 recommended open reduction and repair of the ligaments over nonoperative treatment. In 1988, Fery and Sommelet67 reported 49 cases of dislocations of the SC joint. In these patients, if closed reduction

was not successful, they performed open reduction. In symptomatic

chronic unreduced dislocations, they either performed a myoplasty or

excised the medial end of the clavicle if the articular surfaces were

damaged. They were able to follow 55% of their patients for an average

of more than 6 years. They had 42% excellent results among the

operative cases. Of those patients who were treated with closed

reduction, 58% were satisfied. Ferrandez and colleagues64

reported 18 subluxations and dislocations of the SC joint. Seven had

moderate sprains and 11 had dislocations. Of the 3 patients with a

posterior dislocation, all had symptoms of dysphagia. All of the

subluxations were treated nonoperatively with excellent results. The

remaining 10 patients with dislocations were treated with surgery

(i.e., open reduction with suture of the ligaments and K-wires placed

across the clavicle and the sternum). The wires were removed 3 to 4

weeks following surgery. At 1- to 4-years follow-up, most of the

operative cases had a slight deformity. In 2 patients, migration of the

K-wires was noted but was without clinical significance.

|

|

FIGURE 40-24

CT scan of manubrium showing intrasternal plate insertion. (From Franck WM, Jannasch O, Siassi M, et al. Balser plate stabilization: an alternate therapy for traumatic sternoclavicular instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003;12(3):276-281.) |

strongly urged operative repair of dislocations of the SC joint. In

1989, they reported on 12 patients treated for painful SC joints. The

average time from injury was 1.5 years, and the average follow-up after

surgery was 4.7 years. In 5 patients, the SC joint was stabilized with

a palmaris longus or plantaris tendon graft placed between the first

rib and the manubrium; in 4 patients, the medial 2.5 cm of the clavicle

was resected without any type of stabilization; and in 3 patients, the

clavicle was fixed to the first rib with a fascia lata graft. They

reported good results in four patients, three treated with tendon

grafts and one with a fascia lata graft. They had four fair results and

four poor results in those patients who had only resection of the

medial clavicle. There was little discussion of the patients’

preoperative symptoms, work habits, or range of motion, or the degree

of joint reduction following the surgery. In 1990, Tricoire and

colleagues186 reported six

retrosternal dislocations of the medial end of the clavicle. They

recommended reduction of these injuries to avoid the possible

complications arising from protrusion of the clavicle into the

mediastinum. SC capsulorrhaphy was performed in 2 patients and a

subclavius tenodesis was used in the remaining 4 patients. All joints

were temporarily stabilized with SC pins for 6 weeks. Results were

satisfactory in all cases at a mean follow-up of 27 months.

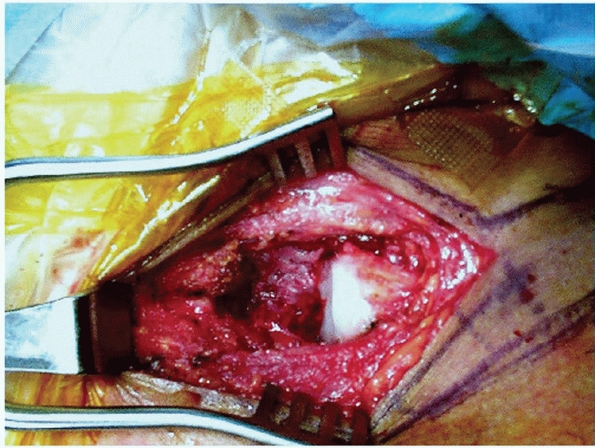

have all recommended excision of the medial clavicle when degenerative

changes are noted in the joint. If the medial end of the clavicle is to

be removed because of degenerative changes, the surgeon should be

careful not to damage the costoclavicular ligament (Fig. 40-25).

recommended a safe resection length that would result in no or minimal

disruption of the costoclavicular ligament of 1.0 cm in men, and 0.9 cm

in women.

be done because it prevents the previously described normal elevation,

depression, and rotation of the clavicle. The end result would be a

severe restriction of shoulder movement (Fig. 40-26).

figure-of-eight bandage for 4 to 6 weeks. When K-wires or Steinmann

pins are used, the patient should avoid vigorous activities until the

pins are removed. The pins should be carefully monitored with

radiographs until they are removed.

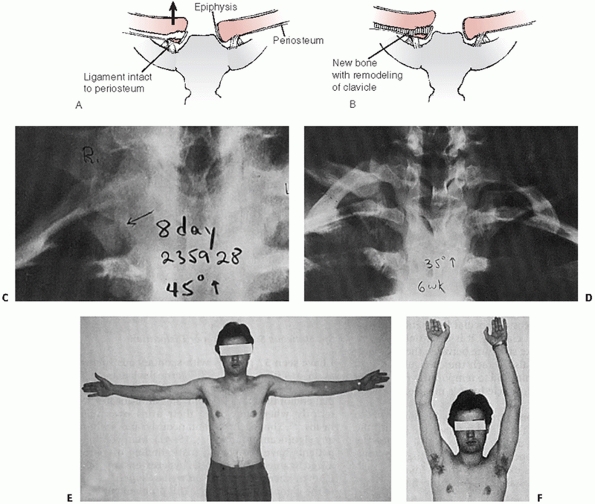

are not dislocations but physeal injuries. Most of these injuries will

heal without surgical intervention. In time, the remodeling process

eliminates

any bone deformity or displacement. Anterior physeal injuries can

certainly be left alone without problem. Posterior physeal injuries

should be reduced. If the posterior dislocation cannot be reduced by

closed means and the patient is having no significant symptoms, the displacement can be observed while remodeling occurs (Fig. 40-27).

It is only in this regard that posterior physeal injuries differ from

posterior SC dislocations in adults. If the posterior displacement is

symptomatic and cannot be reduced closed, the displacement must be

reduced surgically as is required for posterior SC dislocations in

adults (Fig. 40-28).

|

|

FIGURE 40-25 Resection of the medial end of the clavicle, retaining the costoclavicular ligament.

|

|

|

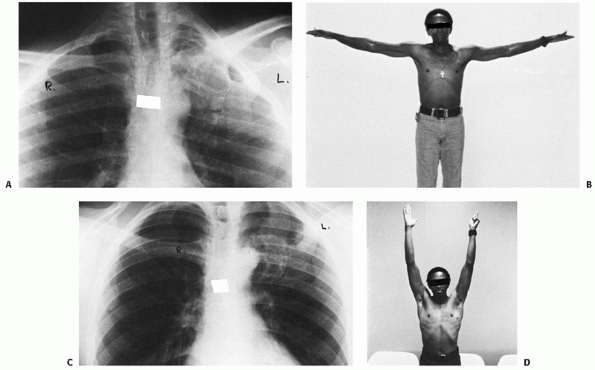

FIGURE 40-26 The effect of an arthrodesis of the SC joint on shoulder function. A.

As a result of a military gunshot wound to the left SC joint, this patient had a massive bony union of the left medial clavicle to the sternum and the upper three ribs. B. Shoulder motion was limited to 90-degrees of flexion and abduction. C. Radiograph after resection of the bony mass and freeing up the medial clavicle. D. The motion of the left shoulder was essentially normal after the elimination of the SC arthrodesis. |

|

|

FIGURE 40-27 A 17-year-old man with a posterior SC physeal injury. A.

The initial injury CT scan displays a physeal fracture-dislocation. The patient had no symptoms of mediastinal compression and was treated with observation after initial attempts at closed reduction were unsuccessful. B. Six months after injury, the CT scan shows healing with remodeling and a reduced SC joint. The patient remained asymptomatic and returned to normal activities. |

is significant and may extend until the 23rd to 25th year. The senior author162

has demonstrated a similar mechanism to support conservative treatment

of adolescent AC joint injuries or “pseudodislocations,” in which there

is a partial tear of the periosteal tube containing the distal

clavicle. The coracoclavicular ligaments remain secured to the

periosteal tube. Because of its high osteogenic potential, spontaneous

healing and remodeling to the preinjury “reduced” position occur within

this periosteal conduit. Waters et al.197

reported successful operative treatment of 13 traumatic posterior SC

fracture-dislocations in children and adolescents, and other authors

have reported the successful treatment of posteriorly displaced medial

clavicle physeal injuries in adolescents.91,206,207

|

|

FIGURE 40-28

CT scan of a 19-year-old patient who was involved in a motor vehicle accident and presented with complaints of chest pain and a “choking sensation” that was exacerbated by lying supine. Note the physeal injury of the medial clavicle and compression of the trachea. |

patient is younger than 25 years, closed reduction, as described for

anterior dislocation of the SC joint, should be performed. The

shoulders should be held back in a clavicular strap or figure-of-eight

dressing for 3 to 4 weeks, even if the reduction is stable. Healing is

prompt, and remodeling will occur at the site of the deformity.

medial clavicle should be performed in the manner described for

posterior dislocation of the SC joint. The reduction is usually stable

with the shoulders held back in a figure-of-eight dressing or strap.

Immobilization should continue for 3 to 4 weeks. If the posterior

physeal injury cannot be reduced, the patient is not having symptoms,

and the patient is younger than 23 years, the physician can wait to see

if remodeling eliminates the posterior displacement of the clavicle.

instability, the importance of distinguishing between traumatic and

atraumatic instability of the SC joint must be recognized if

complications are to be avoided. C. R. Rowe (personal communication,

1988) described several patients who had undergone one or more

unsuccessful attempts to stabilize the SC joint. In all cases, the

patient was able to voluntarily dislocate the clavicle after surgery.

Rockwood and Odor’s165 study of 29

patients with spontaneous subluxation treated nonoperatively with no

failures further reflects the appeal of avoiding surgery in this

population.

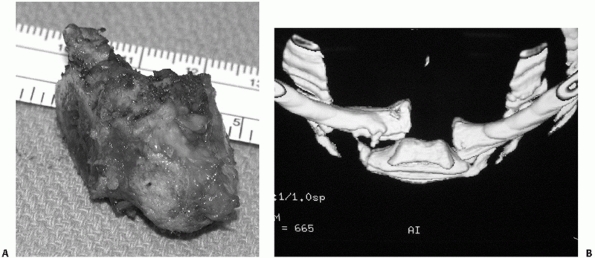

reported a case of spontaneous atraumatic anterior dislocation

secondary to pseudoarthrosis of the first and second ribs. Despite a

6-month course of conservative treatment, this 14-year-old girl was

still painful. A CT scan of the chest with three-dimensional

reconstruction was performed. The scan revealed a pseudoarthrosis

anteriorly between the first and second ribs underlying the medial part

of the clavicle. Resection of the anterior portions of the first and

second ribs containing the pseudoarthrosis relieved her symptoms and

allowed the patient to return to her normal activities. The authors

recommended chest radiographs and a possible CT scan with

three-dimensional reconstruction to completely evaluate an underlying

congenital condition if the subluxation is rigid and unresponsive to

nonoperative care.

described a case of spontaneous atraumatic posterior dislocation of the

SC joint. This occurred in a 50-year-old previously healthy woman who

awoke one morning with a painful SC joint. A CT scan confirmed the

posterior dislocation. She later developed dysphagia, and a closed

reduction was unsuccessful. At 1 year without any other treatment, she

was back to playing golf and was asymptomatic. More recently, Martinez

et al.127 reported on the operative

treatment of a 19-year-old woman with a symptomatic spontaneous

posterior subluxation. The posteriorly displaced medial clavicle was

stabilized with a figure-of-eight suture technique with the use of a

gracilis autograft. At follow-up the patient was pain free; however, a

repeat CT scan demonstrated posterior subluxation of the medial

clavicle with erosion of the clavicle and manubrium. In light of the

recurrence of subluxation after reconstruction, the authors recommended

conservative treatment of atraumatic posterior subluxation of the SC

joint.

cold packs for the first 12 to 24 hours and a sling to rest the joint.

Ordinarily, after 5 to 7 days, the patient can use the arm for everyday

activities.

use a soft, padded figure-of-eight clavicle strap to gently hold the

shoulders back to allow the SC joint to rest. The harness can be

removed after a week or so. Then the arm is placed in a sling for about

another week, or the patient is allowed to return gradually to everyday

activities.

of the SC joint in adults by either a closed reduction or by “skillful

neglect.” Most of the anterior dislocations are unstable, but we accept

the deformity since we believe it is less of a problem than the

potential problems of operative repair and internal fixation.

instances, even knowing that the anterior dislocation will be unstable,

we still try to reduce the anterior displacement. Muscle relaxants and

narcotics are administered intravenously, and the patient is placed

supine on a table with a stack of three or four towels between the

shoulder blades. While an assistant gently applies downward pressure on

the anterior aspect of both of the patient’s shoulders, the medial end

of the clavicle is pushed backward where it belongs. On some occasions,

rare as they may be, the medial clavicle may stay adjacent to the

sternum. However, in most cases, either with the shoulders still held

back or when they are relaxed, the anterior displacement promptly

recurs. We explain to the patient that the joint is unstable and that

the hazards of internal fixation are too great, and we prescribe a

sling for a couple of weeks and allow the patient to begin using the

arm as soon as the discomfort is gone.

patients up to 25 years of age are not dislocations of the SC joint.

Rather, they are type I or II physeal injuries, which heal and remodel

without operative treatment. Patients older than 25 years with anterior

dislocations of the SC joint do have persistent prominence of the

anterior clavicle. However, this does not seem to interfere with usual

activities and, in some cases, has not even interfered with heavy

manual labor.

reduction is stable, we place the patient in either a figure-of-eight

dressing or in whatever device or position the clavicle is most stable.

If the reduction is unstable, the arm is placed into a sling for a week

or so, and then the patient can begin to use the arm for gentle

everyday activities.

and perform a careful physical examination in the patient with a

posterior SC dislocation (Table 40-2). For

every patient, the physician should obtain radiographs and/or a CT

scan. If the patient has distention of the neck vessels, swelling of

the arm, a bluish discoloration of the arm, or difficulty swallowing or

breathing, then the patient should be evaluated by using a CT scan with

contrast of the vascular structures. It is also important to determine

if the patient has a feeling of choking or hoarseness. If any of these

symptoms are present, indicating pressure on the mediastinal

structures, the appropriate cardiovascular or thoracic specialist

should be consulted.

|

TABLE 40-2 Keys to the Diagnosis of Posterior Sternoclavicular Dislocation

|

|

|---|---|

|

required to reduce acute posterior SC joint dislocations. Furthermore,

once the joint has been reduced by closed means, it is usually stable.

anterior or posterior injury of the SC joint could always be made on

physical examination, one cannot rely on the anterior swelling and

firmness as being diagnostic of an anterior injury as the posterior

injuries may create a significant anterior fullness. Therefore, we

recommend that the clinical impression always be documented with

appropriate imaging studies, preferably a CT scan, before a decision to

treat or not to treat is made.

The patient is placed in the supine position with a 3- to 4-inch-thick

sandbag or three to four folded towels placed between the scapulas to

extend the shoulders. The dislocated shoulder should be near the edge

of the table so that the arm and shoulder can be abducted and extended.

If the patient is having extreme pain and muscle spasm and is quite

anxious, we use general anesthesia; otherwise, narcotics, muscle

relaxants, or tranquilizers are given through an established

intravenous route in the normal arm. First, gentle traction is applied

on the abducted arm in line with the clavicle while countertraction is

applied by an assistant who steadies the patient on the table. The

traction on the abducted arm is gradually increased while the arm is

brought into extension (see Fig. 40-19). If

reduction cannot be accomplished with the patient’s arm in abduction,

then we will use the adduction technique of Buckerfield and Castle29 that is described above (see Fig. 40-21).

pop or snap and the relocation can be noted visibly and by palpation.

If the traction techniques are not successful, an assistant grasps or

pushes down on the clavicle in an effort to dislodge it from behind the

sternum. Occasionally, in a stubborn case, especially in a

thick-chested person or a patient with extensive swelling, it is

impossible to obtain a secure grasp on the clavicle with the fingers

alone. The skin should then be surgically prepared and a sterile towel

clip used to gain purchase on the medial clavicle percutaneously (see Fig. 40-20).

The towel clip should encircle the shaft of the clavicle as the dense

cortical bone prevents the purchase of the towel clip into the

clavicle. Then the combined traction through the arm plus the anterior

lifting force on the towel clip will reduce the dislocation. Following

the reduction, the SC joint is usually stable, even with the patient’s

arms at the side. However, we always hold the shoulders back in a

wellpadded figure-of-eight clavicle strap for 3 to 4 weeks to allow for

soft tissue and ligamentous healing.

and erosion of the medial clavicle into any of the vital structures

that lie posterior to the SC joint. Therefore, in adults over the age

of 23, if closed reduction fails, an open reduction should be

performed. It is critical that a thoracic surgeon is immediately

available when the patient is taken to the operating room to intervene

if needed.

evaluate the residual stability of the medial clavicle. It is the same

analogy as used when resecting the distal clavicle for an old AC joint

problem. If the coracoclavicular ligaments are intact, an excision of

the distal clavicle is indicated. If the coracoclavicular ligaments are

gone, then, in addition to excision of the distal clavicle, one must

reconstruct the coracoclavicular ligaments with a SC injury. If the

costoclavicular ligaments are intact, the clavicle medial to the

ligaments should be resected and beveled smooth. If the ligaments are

torn, the clavicle must be stabilized to the first rib. If too much

clavicle is resected, or if the clavicle is not stabilized to the first

rib, an increase in symptoms can result (Fig. 40-29).

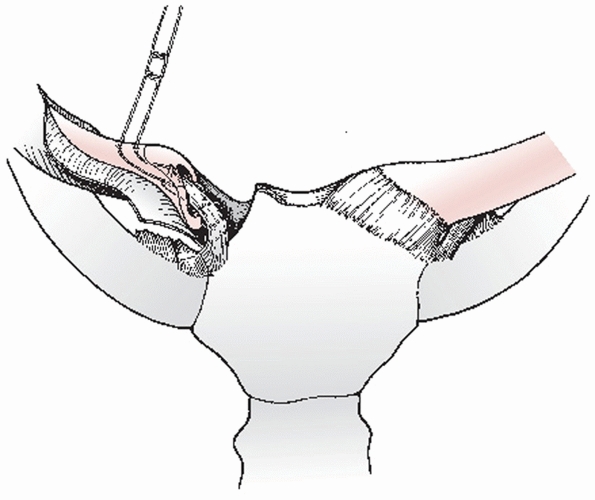

four towels or a sandbag should be placed between the scapulae. The

upper extremity should be draped out free so that lateral traction can

be applied during the open reduction. In addition, a folded sheet

around the patient’s thorax should be left in place so that it can be

used for countertraction when traction is applied to the involved

extremity. An anterior incision is used that parallels the superior

border of the medial 3 to 4 inches of the clavicle and then extends

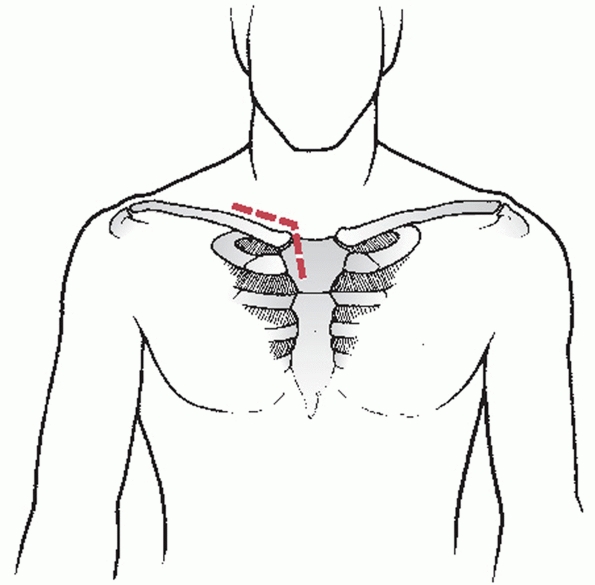

downward over the sternum just medial to the involved SC joint (Fig. 40-30).

The trick is to try to remove sufficient soft tissues to expose the

joint but to leave the anterior capsular ligament intact. The reduction

can usually be accomplished with traction and countertraction while

lifting up anteriorly on a clamp placed around the medial clavicle.

Along with the traction and countertraction, it may be necessary to use

an elevator to pry the clavicle back to its articulation with the

manubrium.

|

|

FIGURE 40-29

This postmenopausal, right-handed woman had a resection of the right medial clavicle because of a preoperative diagnosis of “possible tumor.” The postoperative microscopic diagnosis was degenerative arthritis of the right medial clavicle. After surgery, the patient complained of pain and discomfort, marked prominence, and gross instability of the right medial clavicle. |

|

|

FIGURE 40-30 The proposed skin incision used for open reduction of a posterior SC dislocation.

|

held back, the reduction will be stable if the anterior capsule has

been left intact. If the anterior capsule is damaged or is insufficient

to prevent anterior displacement of the medial end of the clavicle, we

recommend excision of the medial 1 to 1.5 inches of the clavicle and

securing the residual clavicle anatomically to the first rib with 1-mm

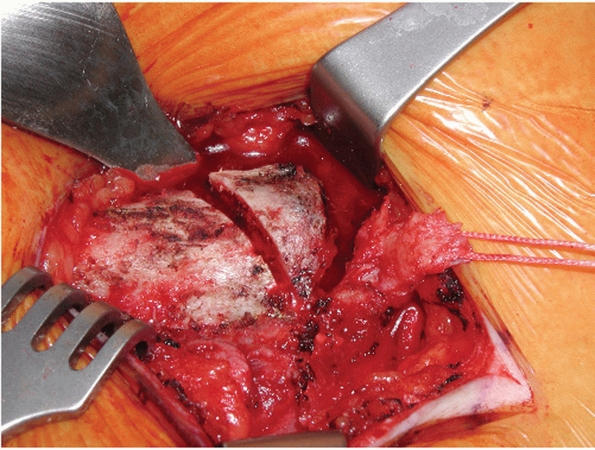

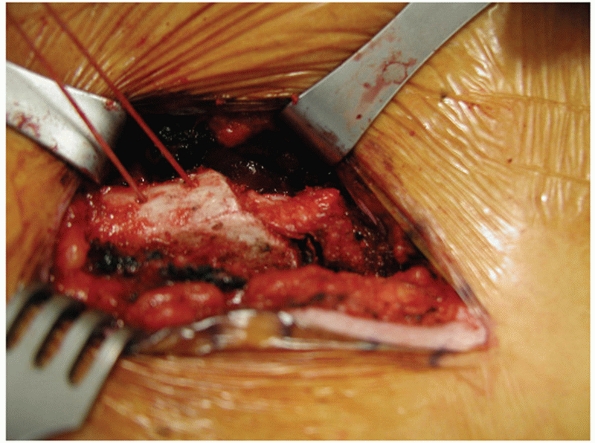

polyester fiber tape. The medial clavicle is exposed by careful

subperiosteal dissection (Fig. 40-31). When

possible, any remnant of the capsular or intra-articular disk ligaments

should be identified and preserved as these structures can be used to

help stabilize the medial clavicle. The capsular ligament covers the

anterosuperior and posterior aspects of the joint and represents

thickenings

of the joint capsule. This ligament is primarily attached to the

epiphysis of the medial clavicle and is usually avulsed from this

structure with posterior SC dislocations. The intra-articular disk

ligament is a very dense, fibrous structure and may be intact. It

arises from the synchondral junction of the first rib and sternum and

is usually avulsed from its attachment site on the medial clavicle. If

the sternal attachment sites of the intra-articular or capsular

ligaments are intact, a nonabsorbable no. 1 cottony polyester fiber

suture is woven back and forth through the ligament so that the ends of

the suture exit through the avulsed free end of the tissue. The medial

1- to 1.5-inch end of the clavicle is resected, being careful to

protect the underlying vascular structures, and being careful not to

damage any of the residual costoclavicular (rhomboid) ligament. The

vital vascular structures are protected by passing a curved Crego

elevator or ribbon retractor around the posterior aspect of the medial

clavicle to isolate them from the operative field during the bony

resection.

|

|

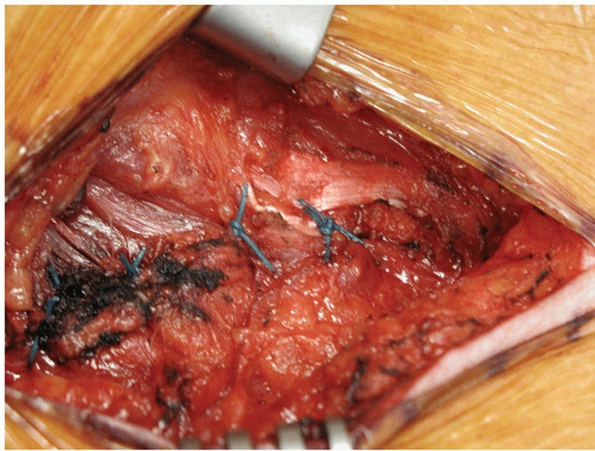

FIGURE 40-31 Subperiosteal exposure of the medial clavicle. Note the posteriorly displaced medial end of the clavicle.

|

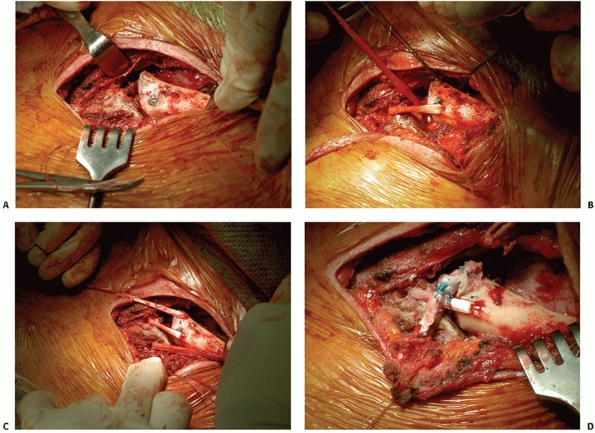

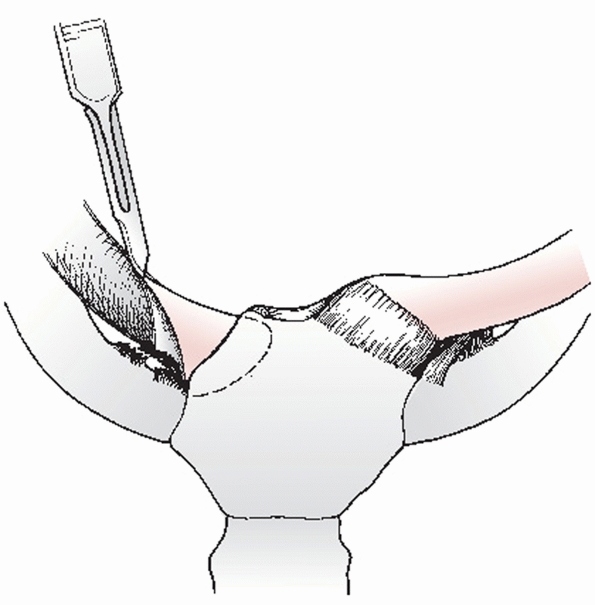

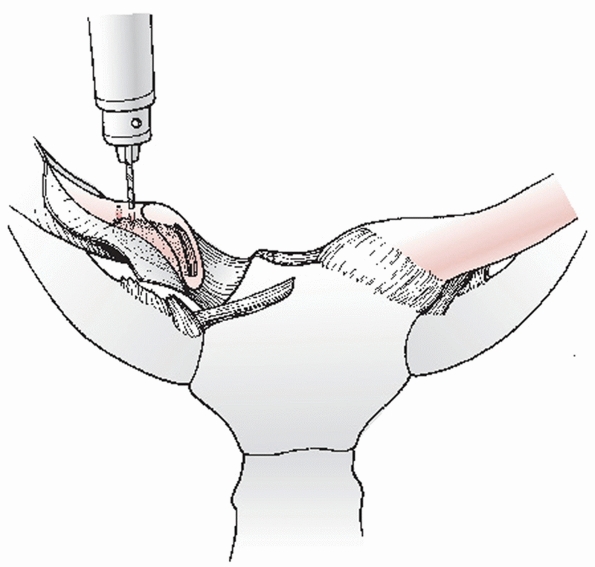

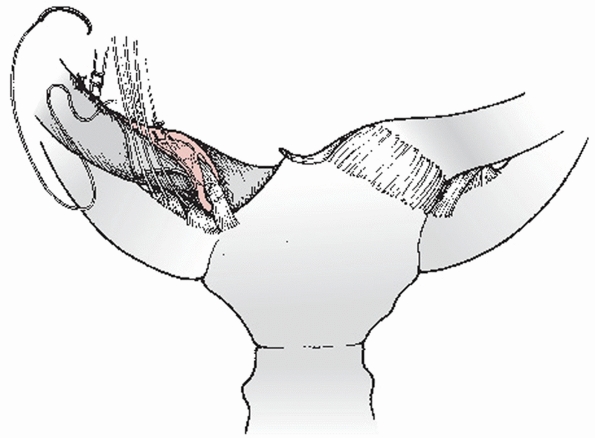

creating drill holes through both cortices of the clavicle at the

intended site of clavicular osteotomy. Following this step, an air

drill with a side-cutting burr is used to complete the osteotomy (Fig. 40-32).

The anterior and superior corners of the clavicle are beveled smooth

with an air burr for cosmetic purposes. The medullary canal of the

medial clavicle is drilled and curetted to receive the transferred

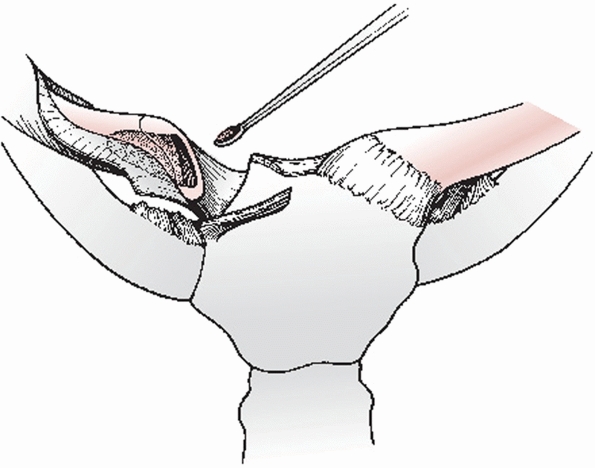

intra-articular disk ligament (Fig. 40-33). Two

small drill holes are then placed in the superior cortex of the medial

clavicle, approximately 1 cm lateral to the site of resection (Fig. 40-34).

These holes communicate with the medullary canal and will be used to

secure the suture in the transferred ligament. The free ends of the

suture are passed into the medullary canal of the medial clavicle and

out the two small drill holes in the superior cortex of the clavicle (Fig. 40-35).

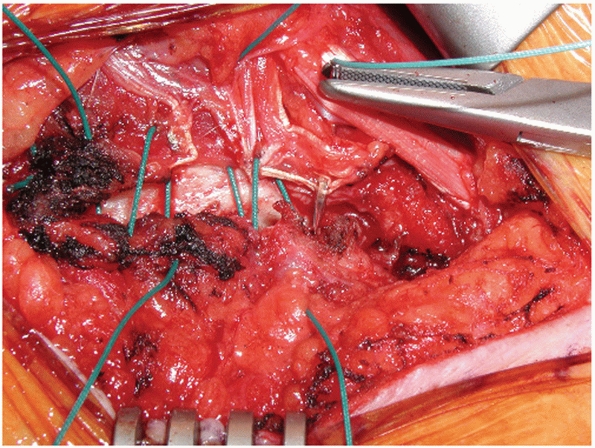

While the clavicle is held in a reduced anteroposterior position in

relationship to the first rib and sternum, the sutures are used to pull

the ligament tightly into the medullary canal of the clavicle (Fig 40-36). The suture is tied, thus securing the

transferred ligament into the clavicle (Fig. 40-37).

The stabilization procedure is completed by passing multiple (five or