Patella and Extensor Mechanism Injuries

Authors: Koval, Kenneth J.; Zuckerman, Joseph D.

Title: Handbook of Fractures, 3rd Edition

Copyright ©2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > IV – Lower Extremity Fractures and Dislocations > 35 – Patella and Extensor Mechanism Injuries

35

Patella and Extensor Mechanism Injuries

PATELLAR FRACTURES

Epidemiology

-

Represent 1% of all skeletal injuries

-

Male-to-female ratio (2:1)

-

Most common age group 20 to 50 years old

-

Bilateral injuries uncommon

Anatomy

-

The patella is the largest sesamoid bone in the body.

-

The quadriceps tendon inserts on the superior pole and the patellar ligament originates from the inferior pole of the patella.

-

There are seven articular facets; the lateral facet is the largest (50% of the articular surface).

-

The articular cartilage may be up to 1 cm thick.

-

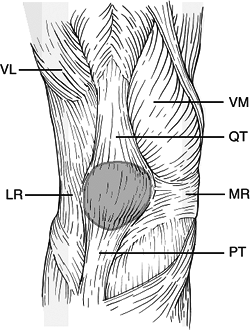

The medial and lateral extensor

retinacula are strong longitudinal expansions of the quadriceps and

insert directly onto the tibia. If these remain intact in the presence

of a patella fracture, then active extension will be preserved (Fig. 35.1). -

The function of the patella is to

increase the mechanical advantage and leverage of the quadriceps

tendon, aid in nourishment of the femoral articular surface, and

protect the femoral condyles from direct trauma. -

The blood supply arises from the geniculate arteries, which form an anastomosis circumferentially around the patella.

Mechanism of Injury

-

Direct: Trauma to the patella may produce

incomplete, simple, stellate, or comminuted fracture patterns.

Displacement is typically minimal owing to preservation of the medial

and lateral retinacular expansions. Abrasions over the area or open

injuries are common. Active knee extension may be preserved. -

Indirect (most common): This is secondary

to forcible quadriceps contraction while the knee is in a semiflexed

position (e.g., in a “stumble” or “fall”). The intrinsic strength of

the patella is exceeded by the pull of the musculotendinous and

ligamentous structures. A transverse fracture pattern is most commonly

seen with this mechanism, with variable inferior pole comminution. The

degree of displacement of the fragments suggests the degree of

retinacular disruption. Active knee extension is usually lost. -

Combined direct/indirect mechanisms:

These may be caused by trauma in which the patient experiences direct

and indirect trauma to the knee, such as in a fall from a height.

Clinical Evaluation

-

Patients typically present with limited

or no ambulatory capacity with pain, swelling, and tenderness of the

involved knee. A defect at the patella may be palpable. -

It is important to rule out an open

fracture because these constitute a surgical emergency; this may

require instillation of 50 to 70 mL saline into the knee to determine

communication with overlying lacerations. Figure

Figure

35.1. Soft tissue anatomy of the patella. VL, vastus lateralis; LR,

lateral retinaculum; VM, vastus medialis; QT, quadriceps tendon; MR,

medial retinaculum; PT, patellar tendon.(From Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown C, et al., eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.) -

Active knee extension should be evaluated

to determine injury to the retinacular expansions. This may be aided by

decompression of hemarthrosis or intraarticular lidocaine injection. -

Associated lower extremity injuries may

be present in the setting of high-energy trauma. The physician must

carefully evaluate the ipsilateral hip, femur, tibia, and ankle, with

appropriate radiographic evaluation, if indicated.

P.371

Radiographic Evaluation

-

Anteroposterior (AP), lateral and axial (sunrise) views of the knee should be obtained.

-

AP view: A bipartite patella (8% of the

population) may be mistaken for a fracture; it usually occurs in the

superolateral position and has smooth margins; it is bilateral in 50%

of individuals. -

Lateral view: Displaced fractures usually are obvious.

-

Axial view (sunrise): This may help identify osteochondral or vertical marginal fractures.

-

-

Arthrograms, computed tomography, and

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are usually unnecessary, but they may

be used to better delineate fracture patterns, marginal fractures, or

free osteochondral fragments.

CLASSIFICATION

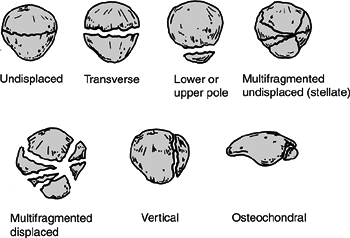

Descriptive (Fig. 35.2)

-

Open versus closed

-

Nondisplaced versus displaced

-

Pattern: stellate, comminuted, transverse, vertical (marginal), polar

-

Osteochondral

P.372

OTA Classification of Patellar Fractures

|

|

Figure 35.2. Classification of patella fractures.

(From Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown C, et al., eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.)

|

See Fracture and Dislocation Compendium at http://www.ota.org/compendium/index.htm.

Treatment

Nonoperative

-

Indications include nondisplaced or

minimally displaced (2- to 3-mm) fractures with minimal articular

disruption (1 to 2 mm). This requires an intact extensor mechanism. -

A cylinder cast or knee immobilizer is

used for 4 to 6 weeks. Early weight bearing is encouraged, advancing to

full weight bearing with crutches as tolerated by the patient. Early

straight leg raising and isometric quadriceps strengthening exercises

should be started within a few days. After radiographic evidence of

healing, progressive active flexion and extension strengthening

exercises are begun with a hinged knee brace initially locked in

extension for ambulation.

Operative

OPEN REDUCTION AND INTERNAL FIXATION

-

Indications for open reduction and

internal fixation include >2-mm articular incongruity, >3-mm

fragment displacement, or open fracture. -

There are multiple methods of operative

fixation, including tension banding (using parallel longitudinal

Kirschner wires or cannulated screws) as well as circumferential

cerclage wiring. Retinacular disruption should be repaired at the time

of surgery. -

Postoperatively, the patient should be

placed in a splint for 3 to 6 days until skin healing, with early

institution of knee motion. The patient should perform active assisted

range-of-motion exercises, progressing to partial and full weight

bearing by 6 weeks. -

Severely comminuted or marginally

repaired fractures, particularly in older individuals, may necessitate

immobilization for 3 to 6 weeks.

P.373

PATELLECTOMY

-

Partial patellectomy

-

Indications for partial patellectomy

include the presence of a large, salvageable fragment in the presence

of smaller, comminuted polar fragments in which it is believed

impossible to restore the articular surface or to achieve stable

fixation. -

The quadriceps or patellar tendons should be reattached without creating patella baja or alta.

-

Reattachment of the patellar tendon close to the articular surface will help to prevent patellar tilt.

-

-

Total patellectomy

-

Total patellectomy is reserved for extensive and severely comminuted fractures and is rarely indicated.

-

Peak torque of the quadriceps is reduced by 50%.

-

Repair of medial and lateral retinacular injuries at the time of patellectomy is essential.

-

-

After either partial or total

patellectomy, the knee should be immobilized in a long leg cast at 10

degrees of flexion for 3 to 6 weeks.

Complications

-

Postoperative infection: Uncommon and is

related to open injuries that may necessitate serial debridements.

Relentless infection may require excision of nonviable fragments and

repair of the extensor mechanism. -

Fixation failure: Incidence is increased in osteoporotic bone or after failure to achieve compression at fracture site.

-

Refracture (1% to 5%): Secondary to decreased inherent strength at the fracture site.

-

Nonunion (2%): Most patients retain good

function, although one may consider partial patellectomy for painful

nonunion. Consider revision osteosynthesis in active, younger

individuals. -

Osteonecrosis (proximal fragment):

Associated with greater degrees of initial fracture displacement.

Treatment consists of observation only, with spontaneous

revascularization occurring by 2 years. -

Posttraumatic osteoarthritis: Present in

more than 50% of patients in long-term studies. Intractable

patellofemoral pain may require Maquet tibial tubercle advancement. -

Loss of knee motion: Secondary to prolonged immobilization or postoperative scarring.

-

Painful retained hardware: May necessitate removal for adequate pain relief.

-

Loss of extensor strength and extensor

lag: Most patients will experience a loss of knee extension of

approximately 5 degrees, although this is rarely clinically significant. -

Patellar instability

P.374

PATELLA DISLOCATION

|

|

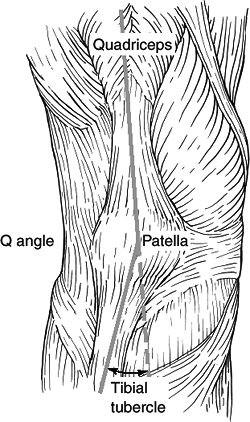

Figure

35.3. The Q (quadriceps) angle is measured from the anterior superior iliac spine through the patella and to the tibial tubercle. (From Insall JN. Surgery of the Knee. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1984.)

|

Epidemiology

-

Patellar dislocation is more common in

women, owing to physiologic laxity, as well as in patients with

hypermobility and connective tissue disorders (e.g., Ehlers-Danlos or

Marfan syndrome).

Anatomy

-

The “Q angle” is defined as the angle

subtended by a line drawn from the anterior superior iliac spine

through the center of the patella, with a second line from the center

of the patella to the tibial tubercle (Fig. 35.3).

The Q angle ensures that the resultant vector of pull with quadriceps

action is laterally directed; this lateral moment is normally

counterbalanced by patellofemoral, patellotibial, and retinacular

structures as well as patellar engagement within the trochlear groove.

An increased Q angle predisposes to patella dislocation. -

Dislocations are associated with patella

alta, congenital abnormalities of the patella and trochlea, hypoplasia

of the vastus medialis, and hypertrophic lateral retinaculum.

Mechanism of Injury

-

Lateral dislocation: Forced internal

rotation of the femur on an externally rotated and planted tibia with

knee in flexion is the usual cause. It is associated with a 5% risk of

osteochondral fractures. -

Medial instability is rare and usually

iatrogenic, congenital, traumatic, or associated with atrophy of the

quadriceps musculature. -

Superior dislocation: This occurs in

elderly individuals from forced hyperextension injuries to the knee

with the patella locked on an anterior femoral osteophyte.

Clinical Evaluation

-

Patients with an unreduced patella

dislocation will present with hemarthrosis, an inability to flex the

knee, and a displaced patella on palpation. -

Lateral dislocations may also cause medial retinacular pain.

-

Patients with reduced or chronic patella

dislocation may demonstrate a positive “apprehension test,” in which a

laterally directed force applied to the patella with the knee in

extension reproduces the sensation of impending dislocation, causing

pain and quadriceps contraction to limit patella mobility.

Radiographic Evaluation

-

AP and lateral views of the knee should

be obtained. In addition, an axial (sunrise) view of both patellae

should be obtained. Various axial views have been described by several

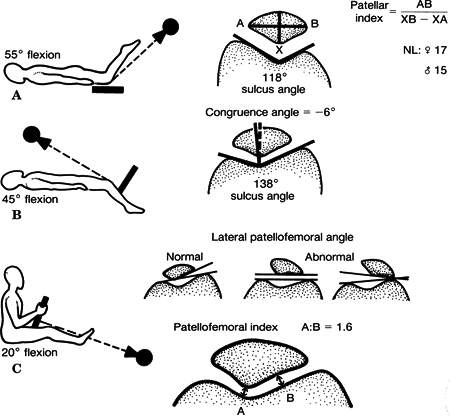

authors (Fig. 35.4):-

Hughston 55 degrees of knee flexion: sulcus angle, patellar index

-

Merchant 45 degrees of knee flexion: sulcus angle, congruence angle

-

Laurin 20 degrees of knee flexion: patellofemoral index, lateral patellofemoral angle

-

-

Assessment of patella alta or baja is based on the lateral radiograph of the knee:

-

Blumensaat line: The lower pole of the

patella should lie on a line projected anteriorly from the

intercondylar notch on lateral radiograph with the knee flexed to 30

degrees. -

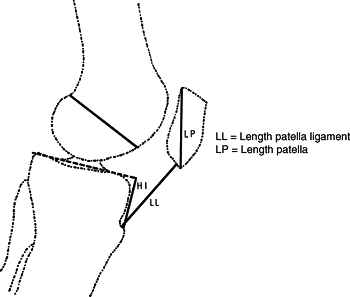

Insall-Salvati ratio: The ratio of the

length of the patellar ligament (LL; from the inferior pole of the

patella to the tibial tubercle) to the patellar length (LP; the

greatest diagonal length of the patella) should be 1.0. A ratio of 1.2

indicates patella alta, whereas 0.8 indicates patella baja (Fig. 35.5).

-

Classification

-

Reduced versus unreduced

-

Congenital versus acquired

-

Acute (traumatic) versus chronic (recurrent)

-

Lateral, medial, intraarticular, superior

Treatment

Nonoperative

-

Reduction and casting or bracing in knee extension may be undertaken with or without arthrocentesis for comfort.

-

The patient may ambulate in locked

extension for 3 weeks, at which time progressive flexion can be

instituted with physical therapy for quadriceps strengthening. After a

total of 6 to 8 weeks, the patient may be weaned from the brace as

tolerated.![]() Figure

Figure

35.4. Representation of the (A) Hughston (knee flexed to 55 degrees)

(B) Merchant (knee flexed to 45 degrees) and (C) Laurin (knee flexed to

20 degrees) patellofemoral views.(From Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults, 5th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.) Figure 35.5. Insall-Salvati technique for measuring patellar height.(From Insall NJ. Surgery New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1984.)

Figure 35.5. Insall-Salvati technique for measuring patellar height.(From Insall NJ. Surgery New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1984.) -

Surgical intervention for acute dislocations is rarely indicated except in displaced intraarticular fractures.

-

Intraarticular dislocations may require reduction with the patient under anesthesia.

-

Functional taping has been described in the physical therapy literature with moderate success.

P.376

P.377

Operative

-

This is primarily used with recurrent dislocations.

-

No single procedure corrects all patellar

malalignment problems; the patient’s age, diagnosis, level of activity,

and condition of the patellofemoral articulation must be taken into

consideration. -

Patellofemoral instability should be addressed by correction of all malalignment factors.

-

Degenerative articular changes influence the selection of the realignment procedure.

-

Surgical interventions include:

-

Lateral release: Indicated for

patellofemoral pain with lateral tilt, lateral retinacular pain with

lateral patellar position, and lateral patellar compression syndrome.

It may be performed arthroscopically or as an open procedure.Medial plication: This may be performed at the time of lateral release to centralize patella.Proximal patella realignment: Medialization of the

proximal pull of the patella is indicated when a lateral release/

medial plication fails to centralize the patella. The release of tight

proximal lateral structures and reinforcement of the pull of medial

supporting structures, especially the vastus medialis obliquus, are

performed in an effort to decrease lateral patellar tracking and

improve congruence of the patellofemoral articulation. Indications

include recurrent patellar dislocations that have not responded to

nonoperative therapy and acute dislocations in young, athletic

patients, especially with medial patellar avulsion fractures or

radiographic lateral subluxation/tilt after closed reduction.Distal patella realignment: Reorientation of the

patellar ligament and tibial tubercle is indicated when an adult

patient experiences recurrent dislocations and patellofemoral pain with

malalignment of the extensor mechanism. This is contraindicated in

patients with open physes and normal Q angles. It is designed to

advance and medialize tibial tubercle, thus correcting patella alta and

normalizing the Q angle.

-

Complications

-

Redislocation: The risk is higher in

patients younger than 20 years at the time of the first episode.

Recurrent dislocation is an indication for surgical intervention. -

Loss of knee motion: This may result from

prolonged immobilization. Surgical intervention may lead to scarring

with resultant arthrofibrosis. This emphasizes the need for aggressive

physical therapy to increase quadriceps tone to maintain patella

alignment and to maintain knee motion. -

Patellofemoral pain: This may result from retinacular disruption at time of dislocation or from chondral injury.

P.378

QUADRICEPS TENDON RUPTURE

-

Typically occurs in patients >40 years old.

-

It usually ruptures within 2 cm proximal to superior pole of patella.

-

Rupture level is often associated with the patient’s age.

-

Rupture occurs at the bone-tendon junction in most patients >40 years old.

-

Rupture occurs at the midsubstance in most patients <40 years old.

-

-

Risk factors for quadriceps rupture

-

Tendinitis

-

Anabolic steroid use

-

Local steroid injection

-

Diabetes mellitus

-

Inflammatory arthropathy

-

Chronic renal failure

-

-

History

-

Sensation of a sudden pop while stressing the extensor mechanism

-

Pain at the site of injury

-

Inability/difficulty weight bearing

-

-

Physical examination

-

Knee joint effusion

-

Tenderness at the upper pole of patella

-

Loss of active knee extension

-

With partial tears, intact active extension

-

-

Palpable defect proximal to the superior pole of the patella

-

If defect present but patient able to extend the knee, then intact extensor retinaculum

-

If no active extension, then both tendon and retinaculum completely torn

-

-

-

Radiographic examination

-

AP, lateral, and tangential (Sunrise, Merchant)

-

Distal displacement of the patella

-

Blumensaat line

-

This is based on a lateral x-ray with the knee in 30 degrees of flexion.

-

The lower pole of the patella should be

at the level of the line projected anteriorly from the intercondylar

notch (Blumensaat line). -

Patella alta possible with patellar tendon rupture and patella baja with quadriceps tendon rupture.

-

-

MRI or ultrasound

-

Useful for unclear diagnosis

-

-

-

Treatment

-

Nonoperative

-

Reserved for incomplete tears in which active, full knee extension is preserved.

-

The leg is immobilized in extension for approximately 4 to 6 weeks.

-

Progressive physical therapy may be required to regain strength and motion.

-

-

-

Operative

-

Indicated for complete ruptures.

-

Reapproximation of tendon to bone using nonabsorbable sutures passed through bone tunnels.

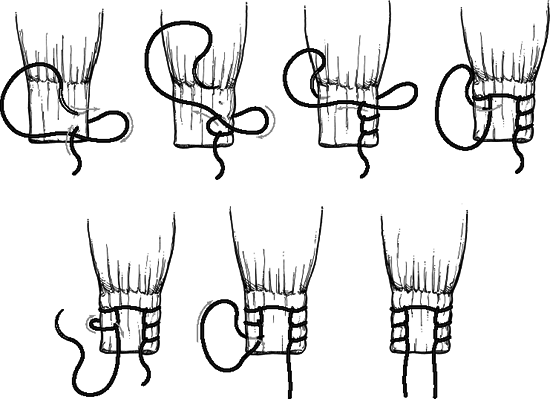

![]() Figure 35.6. Sequential steps of placing Krackow locking loop ligament sutures for tendon or ligament repair.(From Krackow KA, Thomas SC, Jones LC. A new stitch for ligament tendon fixation: brief note. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1980;68:359.)

Figure 35.6. Sequential steps of placing Krackow locking loop ligament sutures for tendon or ligament repair.(From Krackow KA, Thomas SC, Jones LC. A new stitch for ligament tendon fixation: brief note. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1980;68:359.) -

Repair the tendon close to the articular surface to avoid patellar tilting.

-

Midsubstance tears may undergo end-to-end repair after edges are freshened and slightly overlapped (Fig. 35.6).

-

The patient may benefit from

reinforcement from a distally based partial-thickness quadriceps tendon

turned down across the repair site (Scuderi technique). -

Chronic tears may require a V-Y advancement of a retracted quadriceps tendon (Codivilla V-Y-plasty technique).

P.379 -

-

Postoperative management

-

A knee immobilizer or cylinder cast is used for 5 to 6 weeks.

-

Immediate versus delayed (3 weeks) weight bearing is indicated as tolerated.

-

At 2 to 3 weeks, a hinged knee brace is

used, starting with 45 degrees of active range of motion with 10 to 15

degrees of progression each week.

-

-

Complications

-

Rerupture

-

Persistent quadriceps atrophy/weakness

-

Loss of knee motion

-

Infection

-

PATELLA TENDON RUPTURE

-

Less common than quadriceps tendon rupture

-

Most common in patients <40 years old

-

Associated with degenerative changes of the tendon

-

Rupture common at the inferior pole of the patella

-

Risk factors

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

-

Systemic lupus erythematosus

-

Diabetes

-

Chronic renal failure

-

Systemic corticosteroid therapy

-

Local steroid injection

-

Chronic patella tendinitis

-

-

Anatomy of patellar tendon

-

Averages 4 mm thick but widens to 5 to 6 mm at the tibial tubercle

-

Merges with the medial and lateral retinaculum

-

Composition: 90% type I collagen

-

-

Blood supply

-

Fat pad vessels supply the posterior aspect of the tendon via the inferior medial and lateral geniculate arteries.

-

Retinacular vessels supply anterior portion of tendon via the inferior medial geniculate and recurrent tibial arteries.

-

Proximal and distal insertion areas are relatively avascular and subsequently are a common site of rupture.

-

-

Biomechanics

-

The greatest forces are at 60 degrees of knee flexion.

-

Forces through the patellar tendon are 3.2 times body weight while climbing stairs.

-

-

History

-

Often a report of forceful quadriceps contraction against a flexed knee

-

Possible audible “pop”

-

Inability to bear weight or extend the knee against gravity

-

-

Physical examination

-

Palpable defect

-

Hemarthrosis

-

Painful passive knee flexion

-

Partial or complete loss of active extension

-

Quadriceps atrophy with chronic injury

-

-

Radiographic examination

-

AP and lateral x-rays.

-

Patella alta visible on lateral view

-

Patella superior to Blumensaat line

-

-

Ultrasonography an effective means to determine continuity of the tendon

-

However, operator and reader dependent

-

-

MRI

-

Effective means to assess patella tendon, especially if other intraarticular or soft tissue injuries suspected

-

Relatively high cost

-

-

-

Classification

-

No widely accepted means of classification

-

Can be categorized by:

-

Location of tear

-

Proximal insertion most common

-

-

-

Timing between injury and surgery

-

Most important factor for prognosis

-

Acute: within 2 weeks

-

-

-

Treatment

-

Surgical treatment is required for restoration of the extensor mechanism.

-

Repairs are categorized as early or delayed.

-

-

Nonoperative

-

Nonoperative treatment is reserved for partial tears in which patient able to extend the knee fully.

-

Treatment is immobilization in full knee extension for 3 to 6 weeks.

-

-

Early repair

-

The overall outcome is better for a delayed repair.

-

Primary repair of the tendon is performed.

-

Surgical approach is through a midline incision.

-

Patellar tendon rupture and retinacular tears are exposed.

-

Frayed edges and hematoma are debrided.

-

Nonabsorbable sutures are used to repair the tendon to the patella.

-

Sutures are passed through parallel, longitudinal bone tunnels and are tied proximally.

-

Retinacular tears should be repaired.

-

One can reinforce the repair with wire, cable, or tape.

-

One should assess the repair intraoperatively with knee flexion.

-

-

Postoperative management

-

A hinged knee brace locked at 20 degrees.

-

Immediate isometric quadriceps exercises are prescribed.

-

Active flexion with passive extension occurs at 2 weeks; start with 0 to 45 degrees and advance 30 degrees each week.

-

Active extension occurs at 3 weeks.

-

Initial toe-touch weight bearing is gradually advanced to full weight bearing by 6 weeks.

-

Maintain a hinged knee brace, which is gradually increased as motion increases.

-

All restrictions are lifted after full

range of motion and 90% of the contralateral quadriceps strength are

obtained, usually at 4 to 6 months.

-

-

Delayed repair

-

This occurs >6 weeks from the initial injury.

-

It often results in a poorer outcome.

-

Quadriceps contraction and patellar migration are commonly encountered.

-

Adhesions between the patella and femur may be present.

-

Options include hamstring and fascia lata autograft augmentation of primary repair or Achilles tendon allograft.

-

Postoperative management

-

More conservative than with early repair.

-

A bivalved cylinder cast is worn for 6 weeks.

-

Active range of motion is started at 6 weeks.

-

-

-

Complications

-

Knee stiffness

-

Persistent quadriceps weakness

-

Rerupture

-

Infection

-

Patella baja

-

P.380

P.381