NEUROMAS

the injury site seek to grow and reestablish contact with their

respective end organs. Continuity or repair of the Schwann cell

endoneurial tube aids this process. Regenerating axons that do not grow

through the zone of injury and into the distal segment of endoneurial

tube become encased in scar and constitute a forme frustre of peripheral nerve regeneration.

an intact crushed or stretched nerve, or in the terminal end of the

proximal segment of a lacerated nerve, is called a neuroma.

The neuroma is usually well circumscribed, white, and rubbery or firm

in consistency. It may adhere to adjacent scar, skin, muscle, fascia,

tendon, periosteum, or bone.

injury, but only neuromas containing sensory nerve fibers can be

symptomatic. The digital nerves of the hand, the palmar and ulnar

cutaneous nerves, and the dorsal sensory branches of the radial and

ulnar nerves are pure sensory nerves and are especially prone to form

painful neuromas. As many as 30% of neuromas formed by these nerves

become symptomatic (7). Common digital nerves

in ray amputations appear more inclined to be painful than those of

digital amputations, possibly because the former contain more sensory

fibers.

consisting of randomly directed axons in a matrix of proliferative

mesothelial elements, primarily epineurium and endoneurium. There is a

disorganized mixture of axons with a predominance of small-diameter

unmyelinated fibers, frequently in whorl-type patterns surrounded by

Schwann cells, fibroblasts, collagen, macrophages, and capillaries.

Myofibroblasts have been consistently identified by electron microscopy

in painful neuromas. These cells may serve as histologic markers of a

symptomatic neuroma, but their pathophysiologic role remains

undetermined (1,5).

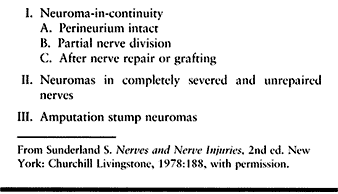

completely severed, unrepaired nerves; and amputation stump neuromas (28).

Neuromas-in-continuity include those with intact perineurium, those

with partial nerve division, and those that form after nerve repair or

grafting.

|

|

Table 53.1. Classification (Sunderland)

|

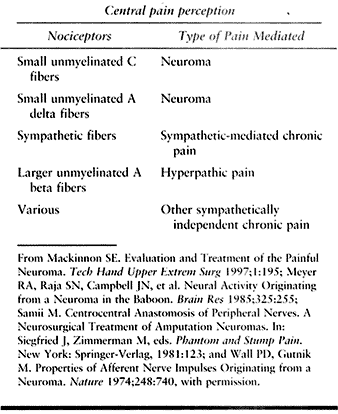

transmitted by afferent small unmyelinated C and A delta fibers. This

picture is sometimes confounded by the involvement of additional

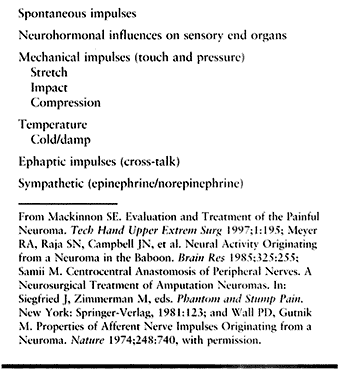

adjacent afferent axons contained within the same sensory nerve (Table 53.2). Afferent impulses are biochemically mediated and may occur spontaneously or be triggered physically (Table 53.3).

In the gate theory of pain, nociceptors do not appear to override other

nociceptors, whereas touch or pressure may do so. Proximity of a

neuroma to skin, to bony prominences, and to the working surface (palm)

of the hand renders it more vulnerable to mechanical impulses (19,26,31).

|

|

Table 53.2. Pathophysiology of Neuroma Pain

|

|

|

Table 53.3. Biochemically Mediated Afferent Impulses

|

predisposition to heightened pain sensitivity and perception.

Psychosocial factors may also play a variable role in the perception

and expression of pain. Such factors include individual personality,

pain tolerance, and secondary gain. These elements may be difficult to

sort out and may confound diagnosis, treatment, and outcome.

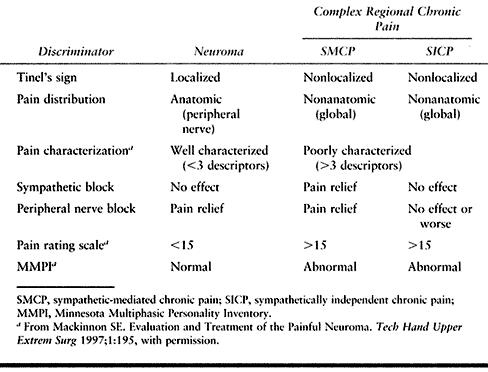

diathesis similar to that seen in patients who develop chronic regional

complex pain occurs more frequently than expected by chance alone.

Symptomatic neuromas of the hand may be complicated by sympathetically

or independently mediated pain. There may be combinations of pain

involvement (see Table 53.2, Table 53.6).

Pain patterns are often refractory to treatment until the noxious

stimulation of the nociceptors is eliminated. Chronicity may lead to

dystrophic tissue changes. The impairment

and

consequent outcome of a symptomatic neuroma are worsened by the

complexity of such additional afferent nerve fiber involvement.

|

|

Table 53.6. Relating Diagnostic Discriminators to Pain Type, Etiology, and Pathophysiology

|

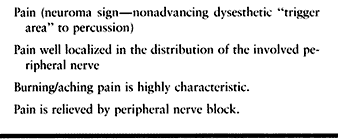

The pain may radiate peripherally in the sensory distribution of the

injured nerve, or proximally in the distribution of the nerve trunk. A

dysesthetic “trigger area” found in the same site may radiate pain

peripherally in the distribution of the injured nerve on percussion.

This pain is equivalent to a nonadvancing Tinel’s sign and may be

called a neuroma sign.

|

|

Table 53.4. Diagnosis of Neuroma

|

anesthetic helps to confirm the diagnosis. Often there is corresponding

sensory deficiency or loss. The history, physical examination,

peripheral and sympathetic nerve blocks, and standardized pain and

psychosocial analysis in various combinations aid in establishing the

diagnosis, sorting out confounding factors, and predicting outcome.

Knowledge of sensory nerve anatomy in the hand and digits helps to

minimize such injuries. In both traumatic and iatrogenic lacerations,

careful identification of transected nerve ends and their repair at the

time of primary wound treatment improves the likelihood of functional

nerve recovery and decreases the risk of symptomatic neuroma formation.

In cases of segmental nerve injury with an identifiable and reparable

distal end, and in a clean and adequately vascularized bed, nerve

grafting accomplishes the same goals. In instances where nerve repair

or reconstruction is not possible and in some amputations, painful

neuromas may develop. The signs are identifiable early, and prompt

treatment is usually more effective than later measures.

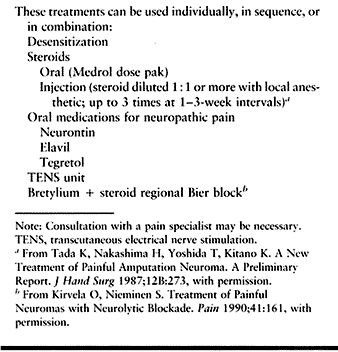

painful neuroma is mild and is treated early. Medications, therapy,

physical modalities, and consultation with a pain management specialist

may be helpful (Table 53.5). If injections of

the neuroma are used, adding triamcinolone acetate to the injection

solution may produce a collagenase effect and soften adjacent scar

sufficiently to be curative or palliative in some cases (23).

Use as much as 10 mg of triamcinolone acetate (i.e., a 10 mg/ml

concentration diluted 1:1 or more with 1% lidocaine) and repeat three

times at 1- to 3-week intervals as needed. Advise patients that

depigmentation of the skin and atrophy of the subcutaneous fat may

accompany triamcinolone injection (15).

|

|

Table 53.5. Nonoperative Treatment

|

demonstrated histologically after application of triamcinolone on a

freshly severed nerve, there is no histologic response to the

application of this steroid in the chronic neuroma. The reason for

improvement or resolution of neuroma pain after steroid injection in

the chronic neuroma remains unclear. The use of collagenase inhibitors

and gangliocidal agents on freshly cut nerve ends is an area of ongoing

investigation that may have future clinical impact (3).

indicated after confirmation of the diagnosis by injection of local

anesthetic and when physical measures such as desensitization and

injection with triamcinolone acetate fail to provide relief. The more

clearly the diagnostic discriminators demonstrate a pure neuroma pain

picture, the better are the outcome expectations following surgery (Table 53.6).

heal them. Take particular care when operating in the vicinity of the

major sensory nerves of the hand, in excision of ganglions. Other

tricky surgeries include decompression of de Quervain’s stenosing

tenosynovitis of the first dorsal compartment, carpal tunnel

decompression, palmar fasciotomy or fasciectomy for Dupuytren’s

disease, A1 pulley release for trigger digits, and tendon repair and reconstruction.

transections of the nerves should be identified and repaired early

whenever possible. Secondarily identified lacerations may merit nerve

grafting if direct suture cannot be performed (6).

In either instance, the preferred treatment for prevention of painful

neuromas is to restore the continuity of the nerve, allowing successful

axonal regeneration across the injury site.

electric current, a variety of artificial (e.g., polyglycolic acid,

collagen-filled) and autogenous (e.g., vein and muscle) conduits, and

the use of nerve allografts with immunosuppressors may soon play a

larger, more definitive role in secondary neuroma treatment by means of

nerve reconstruction (19,20).

Neurovascular island flaps and toe–hand transfers have been successful

for management of refractory digital neuromas when the distal portion

of the involved nerve is not available, when sensory restoration is

important, and in the reconstruction of an amputated digit (17,27).

neuroma-in-continuity forms with the intact perineurium as a result of

repetitive or cumulative trauma (e.g., bowler’s, jeweler’s, or

surgeon’s thumb) and does not respond to nonsurgical measures. A

neurolysis may be performed and the perineural sleeve of scar removed.

In some instances, the nerve may be translocated intact, deep to muscle

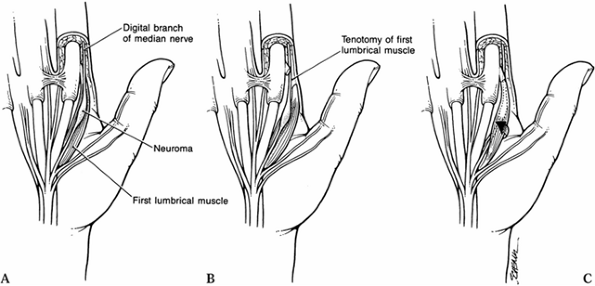

such as the thumb abductor or a lumbrical muscle in the palm (Fig. 53.1) (14).

|

|

Figure 53.1. Submuscular transposition. A: Exposing the radial digital neuroma. B: Division of the lumbrical muscle. C: Mobilization of the lumbrical muscle and digital nerve.

|

-

Expose the radial digital neuroma at the base of the index fingers adjacent to the lumbrical muscle.

-

Divide the lumbrical muscle near its insertion.

-

Mobilize the lumbrical muscle and digital nerve.

-

Translocate the digital nerve beneath the muscle.

-

Reapproximate the muscle insertion by suture.

-

The lumbrical muscle now overlies and protects the neuroma-in-continuity.

are that each digital nerve end be identified, mobilized, and placed

under gentle tension, and that the sharply divided end be allowed to

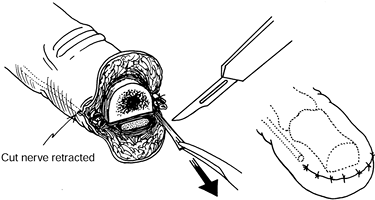

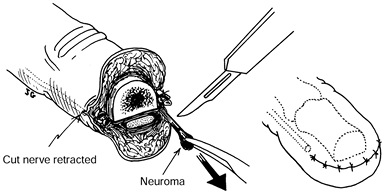

retract 6–10 mm into healthy tissue proximal to the amputation stump (Fig. 53.2) (30).

|

|

Figure 53.2. Simple immediate or early primary excisional neurectomy.

|

-

Identify and ligate the digital arteries.

-

Place the digital nerve under gentle tension.

-

Cut the digital nerve as far proximal as possible.

-

Allow the cut nerve end to retract 6–10 mm proximal to the amputated bone end.

nerve ligation, and capping of the nerve end have been tried with

varying success and are not recommended.

and does not respond satisfactorily to triamcinolone acetate injection,

desensitization, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, or other

nonoperative measures. For excisional neurectomy to be successful in

the treatment of amputation neuromas, a stump revision must be

performed if there is a bony prominence representing a potential source

of trauma to the nerve end. Simple neuroma resection has become a

benchmark by which other measures may be gauged (Fig. 53.3).

|

|

Figure 53.3. Funicular excision with epineural ligation. A: Mobilization of the epineurium. B: Cutting the funicular ends. C,D: Restoration and suturing of the epineurium.

|

-

Dissect the digital nerve and its neuroma away from the digital artery.

-

Place the digital nerve and its neuroma under gentle tension.

-

Resect the neuroma by cutting the digital nerve as far proximal as possible.

-

Allow the cut nerve end to retract into unscarred soft tissue 6–10 mm from the amputated bone end.

simple excisional neurectomy is one of initial improvement followed by

recurrent symptoms as the anatomic neuroma reforms in its new position.

A second excisional neurectomy may occasionally be helpful after a

failed initial procedure, but subsequent procedures offer diminishing

returns (30).

influences of sensory end organs, particularly those of the skin.

Transposition may remove the nerve end from local neurohormonal

influences at the site of injury. Transposition of a severed nerve end

to a protected environment away from skin, bony prominences, and the

working surface of the hand and avoidance of tension on the nerve may

provide the best physical protection of the severed proximal nerve end.

It may prevent, improve, or eliminate symptoms.

poor full-thickness skin coverage may often be protected by submuscular

translocation or by local or distal flap coverage, it may be easier and

more practical to transpose the nerve to a protected environment. An

area with better blood supply, less scar, and less tension seems to

have a salutary effect on a painful neuroma. Transposition has the

additional benefits of physically removing the nerve end from areas of

direct trauma, such as the working surface of the hand, bony

prominences (especially amputated bone ends), severely scarred areas,

and local neurohormonal influences. There are three types of

translocation procedures for cut nerve ends: subcutaneous,

intramuscular, and intraosseous.

-

To protect the nerve end or the neuroma

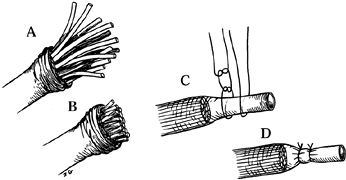

from direct trauma in the area to which it is transposed, place a

resorbable suture through the epineurium without violating the nerve,

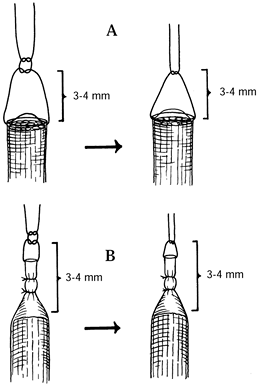

or through the capsule without violating the neuroma (Fig. 53.4, Fig. 53.5) (4).![]() Figure 53.4. Suture techniques for nerve transposition. A: Unligated nerve end. B: Ligated nerve end.

Figure 53.4. Suture techniques for nerve transposition. A: Unligated nerve end. B: Ligated nerve end. Figure 53.5. Subcutaneous dorsal web space transposition. A: Dissection and mobilization of the digital nerve and its neuroma. B: Suturing the perineurium. C: Tying the suture over a dental roll.

Figure 53.5. Subcutaneous dorsal web space transposition. A: Dissection and mobilization of the digital nerve and its neuroma. B: Suturing the perineurium. C: Tying the suture over a dental roll. -

Tie a knot 3–4 mm distal to the freshly

cut nerve end or neuroma to prevent its direct contact with the

structures to which it is transposed. -

After transposition of any type, inspect the nerve trunk to be certain it is neither under tension nor kinked.

-

In diffusely dysesthetic digital

amputation stumps with one palpable sensitive digital neuroma and one

nonpalpable insensitive neuroma, consider transposing both nerves. If

transposition is not done, the remaining digital neuroma sometimes

becomes significantly more painful, even though the transposed neuroma

becomes asymptomatic.

-

Mobilize the epineurium proximally exposing the fu-nicular ends.

-

Cut the funicular ends proximally.

-

Restore and suture the epineurium over the cut funicular ends without injuring them.

-

Dissect and mobilize the digital nerve

and its neuroma. Dissect the neuroma and its fibrous capsule in

continuity with its nerve proximally and mobilize it so that it can be

translocated without tension. -

Protect the digital artery.

-

Ensure hemostasis.

-

Resect the neuroma. Select a dorsal,

scar-free site away from bony prominences and local pressure or trauma.

The area chosen should place the neuroma dorsal to muscle, positioning

the muscle between the neuroma and the surface of the hand (13,18).

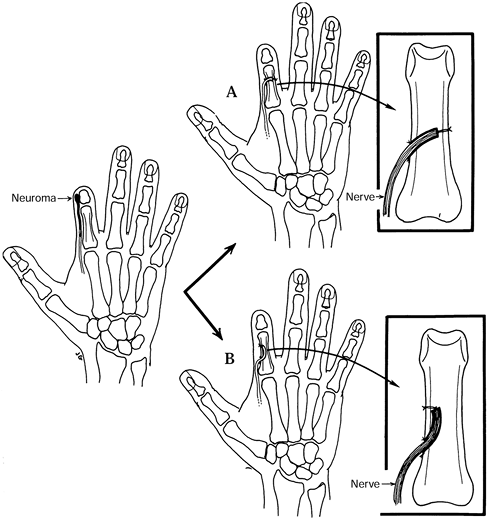

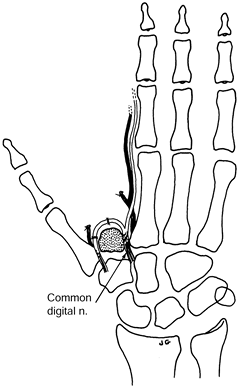

The web space is preferred for neuromas of the digital stumps and the

area between or adjacent to the metacarpals for those involving the

common digital nerves of the palm (Fig. 53.4, Fig. 53.5 and Fig. 53.6).![]() Figure 53.6. Intraosseous transposition. A: Drilling of two small holes in the far cortex opposite the initial drill hole. B: Drill two small holes in the near cortex distal to the initial drill hole.

Figure 53.6. Intraosseous transposition. A: Drilling of two small holes in the far cortex opposite the initial drill hole. B: Drill two small holes in the near cortex distal to the initial drill hole. -

Attach two fine sutures to the perineurium only, on opposite sides of the resected distal tip of the nerve.

-

Tunnel under or into the subcutaneous fat in the adjacent dorsal web space.

-

Tie a knot 3–4 mm distal to the nerve

fascicles to prevent them from directly abutting soft tissues, muscle,

or bone after transposition. -

Bring the needles out through the skin in the proximal portion of the dorsal web space.

-

Transpose the nerve into the depths of the subcutaneous tunnel in the dorsal web space.

-

Be sure the nerve is not kinked.

-

Be sure the nerve is not under excessive tension.

-

Tie the suture over a dental roll.

advocated, there is now evidence from both laboratory and clinical

studies that neuroma formation is suppressed by placing the transected

proximal nerve end directly into muscle substance (19).

The operative technique is similar to that of dorsal subcutaneous

transposition. Although the procedure of neuroma excision and

implantation of the transected nerve end into the brachioradialis has

been a successful method of treating symptomatic neuromas of the

superficial radial nerve, similar procedures placing the digital nerves

into the intrinsic muscles of the hand have been disappointing. Perhaps

muscle contracture, a relatively large muscle excursion in relation to

muscle size, pressure, traction on the nerve during use, or some

combination of these is at fault. Therefore, this procedure is not

currently recommended.

sensory nerve or of a neuroma with sensory neuroma resection produces

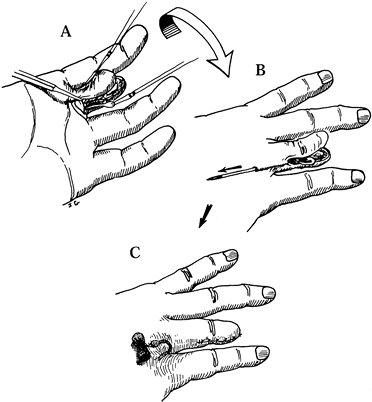

results at least comparable to those of subcutaneous transposition (2,9,12,21,22). Either of two techniques for intraosseous transposition may be used (Fig. 53.7).

|

|

Figure 53.7. Simple late excisional neurectomy.

|

-

Dissect and mobilize the digital nerve and its neuroma.

-

Protect the digital artery.

-

Ensure hemostasis.

-

Resect the neuroma.

-

Attach two fine sutures to the perineurium only, on opposite sides of the resected tip of the nerve.

-

Drill a hole in the adjacent phalanx

large enough to accommodate the nerve without constriction and proximal

enough to avoid excessive nerve tension. -

Drill two small holes in the far cortex

opposite the initial drill hole using a small Kirschner wire or drill.

Pass the needles and suture ends through these holes. Tie the suture

over a dental roll or make a small skin incision prior to passing the

suture ends and tie them directly on the bone. Two alternative methods

follow: -

Alternative A: Drill two small holes in

the near cortex distal to the initial drill hole using a small

Kirschner wire or drill. Pass the needles and suture ends through these

holes. Tie the sutures directly on the bone. -

Alternative B: Suture the epineurium to

the periosteum adjacent to the initial hole and leave the nerve end

free within the bone. -

Be sure the nerve is not kinked.

-

Be sure the nerve is not under excessive tension.

nerve end against intramedullary bone. The epineurium may also be

sutured to the periosteum or to the bone at the site of its entry into

the intramedullary canal. In either technique, there should be no

tension on the nerve at any point. The angle that the transposed nerve

makes as it enters and courses through the bone should not be too

acute. In transposing a transected nerve into bone, it is important to

avoid tension on the proximal stump in any position in the arc of

motion of adjacent joints.

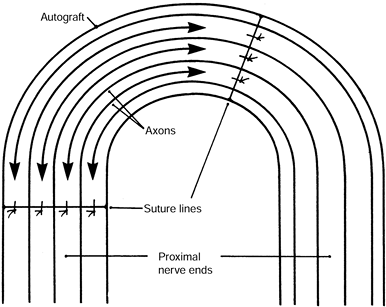

fascicles of the same diameter to either end of an autologous nerve or

fascicle transplant, artificially created by sharply dividing and then

resuturing one of the nerves or fascicles 5–10 mm from its cut end (Fig. 53.8).

|

|

Figure 53.8. Centrocentral coaptation for index finger ray amputation.

|

-

Ligate the digital arteries.

-

When done as a secondary procedure, resect the neuromas.

-

Intercalate a section of digital nerve

graft (from the amputated finger or other donor site) between the

digital nerves of the index finger. -

The nerve graft should be at least 5–10 mm in length and of similar diameter to the digital nerves.

-

Allow no tension at the suture lines.

-

Protect with adequate cover.

-

Keep away from skin suture lines.

-

Primary centrocentral coaptation is preferred, although secondary centrocentral coaptation can be done.

nerve or fascicle and the transplant, so that the physiologic

regeneration of the central axons course past the suture lines and

bypass each other at the midportion of the transplant (Fig. 53.9).

|

|

Figure 53.9. Close-up of the centrocentral coaptation. The axons (arrows) course past the suture lines and interdigitate at the midportion of the intercalated nerve graft.

|

-

The axons recognize each other as “nontarget structures.” Therefore, the neuroma is small and nonsensitive.

-

Increased intraneural pressure reduces

axoplasmic flow, centrally inhibiting neural protein synthesis and

stopping axonal growth after 3–5 mm of axonal overlap. -

The nerve fascicles’ insulation from neurotrophic growth factors also inhibits neuroma formation.

performed at the same area, the suture lines may be offset stepwise to

minimize the chances of axonal compression by interfascicular

connective tissue proliferation. Protect the centrocentral junction by

adequate full-thickness cover and place it as far from the skin suture

lines as possible. This procedure is excellent for cases of digital or

ray amputation. It can be performed as a primary or secondary procedure

(8,10,11,16,26,27,29).

2–5 mm within the midportion of the transplant, as the increased

intraneural pressure created by this juncture mechanically reduces its

axoplasmic flow; this centrally inhibits neural protein synthesis. This

mechanism also minimizes the size of the intraneural neuroma within the

transplant.

neuroma formation by centrocentral union is that macromolecular

proteins in the distal nerve stump and sensory receptors (i.e.,

target-derived neurotrophic factors) stimulate axonal regeneration

locally at the site of injury and centrally at the nerve cell body by

retrograde axoplasmic transport. They may also guide the regenerating

axons to their target end organs after nerve repair or grafting is

performed. In the case of an unsatisfied proximal nerve end, these

neurotrophic factors may contribute to neuroma formation and its

symptoms. Centrocentral coaptation may insulate the central nerve

segment or the fascicle stumps from neurotrophic influences and confine

the regenerating axons to a nontarget environment, allowing the

regenerative process to cease.

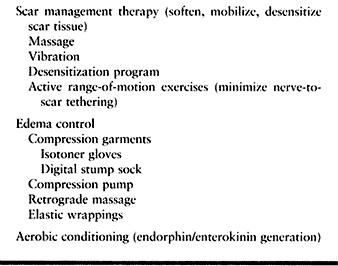

dressing until pain at the operative site is minimal. In the case of a

successful operation, it takes 3 to 6 weeks for the pain to subside.

Thereafter, have the patient remove the protective dressing or splint 3

to 4 times each day for therapy. Therapy includes joint motion and

tendon excursion exercises, as well as scar softening, mobilization,

and desensitizing measures. Use warm water soaks, massage, and active

range-of-motion exercises.

are capable of gliding a limited distance in the tissue that surrounds

them. To the extent that this gliding is impaired by scar adhesion,

traction on the nerve may occur and may produce symptoms. We attempt to

restore gliding by early motion, scar massage, softening, mobilization,

and desensitization after neuroma surgery. Aerobic conditioning has

proven helpful to some patients (Table 53.7).

|

|

Table 53.7. Postoperative Care and Rehabilitation

|

used to diminish swelling. The Isotoner glove is worn at night.

Vibration may be soothing and softens, mobilizes, and desensitizes the

scar area. Other physical measures to soften and desensitize the scar

include Silastic elastomer (Smith & Nephew, Menomonee Falls, WI),

maintained in place with Coban (Medical Products Division of 3M, St.

Paul, MN), which may be worn at night. Paraffin wax bath and

phonophoresis deliver deep heat and may be soothing. Carefully combined

with massage, they may help to stretch and soften scar. Continue these

methods until the patient’s pain is well within tolerance, resolved, or

has reached a point of maximum medical improvement.

physician and a program directed at functional recovery,

desensitization of the stump and scar, and early return to manual

activities (including work and recreation) play a very important role

in patient recovery.

single measure to prevent a symptomatic neuroma. Nerve grafting and

neurotized tissue transfer are a close second. These methods may also

restore sensory loss. Decompression and translocation of an intact

neuroma in continuity is also a highly reliable procedure. Each of

these procedures reestablishes nerve continuity. They are at least 80%

to 90% successful in avoiding or eliminating symptoms or making them

tolerable.

Repetition of this procedure for initial failure is also about 65%

effective. After two unsuccessful attempts at simple excisional

neurectomy, there is little yield from repeating the procedure again.

usually used as salvage procedures for symptomatic neuromas in which

the distal nerve segment is not available and in which the

reestablishment of sensation is not critical. These procedures are 80%

to 90% successful.

with complex pain. Patients who do not have adverse psychosocial

factors fare better than those who have them (25).

division can be achieved by repair using direct suture in freshly

lacerated lesions and by nerve grafting, primarily or secondarily, in

cases with nerve loss and those in which direct suture cannot be

accomplished without tension. In elective digital amputations or ray

resection, centrocentral coaptation or transposition may be selected

for digital nerve management. For traumatic amputations, the condition

of the wound at the time of surgery may dictate whether the transected

nerves are managed by simple excision or by a nerve-manipulating

procedure. If the wound is contaminated or if additional dissection

would jeopardize tissue viability, the transected nerve ends should be

managed by simple excision. Centrocentral coaptation or transposition

of the neuroma may be deferred and performed as a delayed primary

procedure when wound conditions permit or secondarily if a symptomatic

neuroma develops. Naturally, prevention of a symptomatic neuroma is

preferable to treatment of one.

include nerve grafting if a distal nerve end is available.

Decompression and submuscular translocation are quite reliable in

managing neuromas caused by repetitive or cumulative trauma that form

in continuity with the perineurium intact. Dorsal subcutaneous or

intraosseous transposition is effective in treating symptomatic

neuromas when no suitable distal nerve exists. Centrocentral coaptation

is an excellent method of managing transected digital nerves. Although

setting the standard for comparison, simple excision does not provide

as good or as reliable results for established neuromas as do the other

procedures described in this chapter.

symptomatic neuromas include removing the free nerve end from areas of

scarring, bony prominences, and the working surface of the hand.

Translocation or transposition can also remove a freshly cut nerve end

from local

neurohormonal

influences arising from denervated cutaneous sensory end organs. The

free nerve end must be under no tension and should lie in or adjacent

to well-vascularized tissues. There must be no kinking of the

translocated nerves.

may be excessive nerve tension, pullout, or kinking. Consider

performing a second surgical procedure to investigate the causes and

redo the transposition or relocate the nerve. The same is true in

failure of centrocentral coaptation.

suppressed by intramuscular transposition of the proximally transected

nerve, this method has proved ineffective for controlling neuroma pain

in the hand. Intrinsic muscle contracture causes a relatively large

excursion in relation to muscle size; pressure and traction have been

implicated.

correlates with the time from its formation. Chronic pain syndromes and

the establishment of central pain are time related and often involve

psychosocial and economic factors. The longer a painful neuroma goes

untreated, the less likely it is that any modality can be effective.

Treatment should be completed expeditiously, and the patient should

return to work, even if performing only light duty, as soon as possible.

treatment of a painful neuroma may be successful and is indicated. If a

second operation does not solve the problem, additional surgery

produces sharply diminished returns. Although another operation is

sometimes indicated, the physician should also consider alternatives.

The patient can, for example, be referred to a multidisciplinary pain

clinic as an alternative to additional surgery. These clinics provide

diagnostic and therapeutic nerve blocks. They are particularly helpful

with complex regional independent and sympathetically mediated pain.

moderated symptoms in some patients with complex pain components. There

has also been some success with both peripheral nerve and central

spinal cord stimulators. Although these methods for managing chronic

pain are not a panacea, some otherwise refractory problems have

responded favorably.

scheme: *, classic article; #, review article; !, basic research

article; and +, clinical results/outcome study.

MA, Hurst LC, Ellstein J, McDevitt CA. The Pathobiology of Human

Neuromas. An Electron Microscope and Biomechanical Study. J Hand Surg 1985;10B:49.

MD, Bunke JH, Campagna-Pinto D. Experimental Treatment of Neuromas in

the Rat by Retrograde Axioplasmic Transport of Ricin with Selective

Destruction of Ganglion Cells. J Hand Surg 1989;14A:710.

J, Barbera J, Abellan MJ, et al. Centro-central Anastomosis in the

Prevention and Treatment of Painful Terminal Neuroma. J Neurosurg 1985;63:754.

M. Centrocentral Anastomosis of Peripheral Nerves. A Neurosurgical

Treatment of Amputation Neuromas. In: Siegfried J, Zimmerman M, eds. Phantom and Stump Pain. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1981:123.

JW, Booth DM. Treatment of Painful Neuromas of Sensory Nerves in the

Hand: A Comparison of Traditional and Newer Methods. J Hand Surg 1976;1:144.