GUNSHOT, CRUSH, INJECTION, AND FROSTBITE INJURIES OF THE HAND

III – THE HAND > Trauma > CHAPTER 45 – GUNSHOT, CRUSH, INJECTION,

AND FROSTBITE INJURIES OF THE HAND

are frequently life changing. Our hands define our vocations,

avocations, pleasures, and even expression. Treatment of these

injuries, then, must take into account the person whom the tragedy has

struck and use all measures necessary to maximize the return toward

normalcy.

different structures in efficient juxtaposition. Planning the treatment

of injuries must take into account the rehabilitation of each

structure. For example, a crushing injury at the metacarpal level with

dorsal skin loss, extensor tendon injury, and fractures may require

stable bony fixation for early mobilization, possible free tissue

transfer for skin coverage and tendon gliding, and even possible

combination flaps such as the dorsalis pedis flap to include extensor

tendons. Isolated treatment of the bony injury may

result

in a favorable radiograph but would certainly compromise hand function.

Treatment of the soft tissue defect without stable bony fixation would

be equally disastrous.

as “go to the bone and stay there” to better appreciate the importance

of soft tissue treatment and healing. Levin coined the term orthoplastic

to emphasize the interplay between soft tissue management and bone

reconstruction. Reconstruction of the soft tissue envelope demands

definition of the layers deficient as well as the size of the defect

before outlining a plan that will treat both the bone and soft tissue

to the best advantage (38).

These were divided into three groups based on the timing of the

free-flap transfer, ranging from less than 72 h to greater than 3

months. He showed that early coverage resulted in a lower rate of

infection, fewer hospital days and operations, and earlier bone

healing. Drawbacks of the study include the wide range of the middle

group (72 h to 3 months). The study did emphasize the supreme

importance of adequate initial debridement, which often will obviate

later debridement and in some cases allow soft tissue coverage at the

initial operation (24).

paint injection, and frostbite is reviewed in this chapter, beginning

with emergency room evaluation and treatment, surgical planning,

staging, options, and, finally, postoperative rehabilitation.

history has made its greatest advances in wartime. More than half of

war wounds involve the extremities, and a fifth of these are hand

wounds (11). Regrettably, injuries once

commonplace only in times of war are now regular and expected

occurrences in emergency rooms around the country. Specific injuries of

the hands are seldom themselves life threatening but are frequently

associated with other wounds and, as a result, are often complicated by

delay in treatment. Maximal function and minimal long-term disability

will be achieved only with thoughtful treatment, couched in a basic

knowledge of ballistics and wound personality, appropriate emergency

care, and reconstruction options.

basis of the velocity of the bullet, with the difference between low

and high velocity ranging from 1,100 to 3,000 ft/s (18,32).

Velocity increases only the potential for increased tissue disruption;

other factors determine the reality of that potential (fragmentation,

yaw, missile shape, and deformation). Another popular reference is to

the kinetic energy of the bullet, an immeasurable concept that reveals

nothing of the magnitude, type, or location of tissue damage or the

forces that cause tissue disruption and distracts from these crucial

elements. Tissue damage from bullet projectiles occurs through two

mechanisms: first, tissue crush by the projectile and any resultant

secondary projectiles; and second, tissue stretch from temporary

cavitation, which occurs in a radial fashion along the course of the

bullet (19,20 and 21,32). Direct tissue damage from the projectile is increased by deformation of the bullet, fragmentation, and bullet yaw and tumble.

itself. Tissues such as skeletal muscle have a high level of elasticity

and are therefore less affected by temporary cavity displacement

pressure (4 atm) than less elastic tissue such as brain, liver, or

spleen. Indeed, most injury to extremities is the result of structures

directly hit by the intact bullet, bullet fragments, or secondary

missiles (19,32,33).

Since the Hague Conferences of 1899 and 1907, full metal jacketed

bullets were adopted by the military of all major countries to limit

unnecessary suffering of war (53). These

standards are obviously not applied to civilian weapons. If a full

metal jacketed bullet and a soft or hollow point bullet are fired from

the same rifle, the latter will result in a much more dramatic wound

from both increased yaw and deformation.

Round projectiles have poor ballistic properties, losing much of their

energy in flight through the air. Their wounds are then reflective of

the increased mass of the projectiles, not their high velocity. The

greater the choke of the barrel, the less spread of pellets at any

given distance. Decreasing the choke (“sawed-off shotgun”) increases

both the ability to conceal the weapon and the ability to hit multiple

targets with one shot as a result of increased dispersion of the

pellets.

|

|

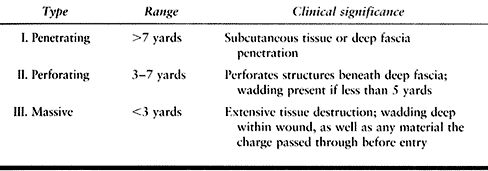

Table 45.1. Classification of Shotgun Wounds

|

increase in muzzle velocity possible with a longer barrel. The M-16

rifle represented a trend toward projectiles of lower weight and very

high velocity (increasing the rounds that a soldier may carry). The

resultant poor ballistic coefficient and high drag of the lighter

bullet demands a closer target but results in greater tissue

destruction, maximizing the wound channel from its high yaw angle after

contact (3). It is possible to have both a

small entrance and exit wound even in the setting of massive tissue

destruction as the bullet yaws early and rights itself for exit. Damage

by a military rifle before it yaws cannot be distinguished from that

caused by a handgun, even by experts (18).

The shorter barrel results in lower bullet velocity and less accuracy.

A revolver is distinguished from a pistol

by

its cylinder versus the vertical magazine in the handle of the pistol.

Innovation in the characteristics of the bullets has dramatically

changed the level of tissue destruction even in the setting of

decreased velocity. For example, a Glasser safety slug is a lightweight

hollow copper bullet filled with number 12 birdshot pellets with a top

sealed with a plastic cap. It ruptures on contact, releasing pellets in

every direction, each of which rapidly decelerates, releasing its

energy quickly (3).

according to 1994 estimates. This represents 200 million guns, 60

million handguns, and 3 million assault rifles (50).

Washington and Lee reported in 1995 that 14 children younger than 19

years old will die in gun-related incidents each day in the United

States (70). Ordog reported on 16,316 patients

with 18,349 extremity gunshot wounds treated in Los Angeles from 1978

to 1992. The mean age was 24 years old, and 94% were male; 83% were

from handguns, 6% rifles, and 6% shotguns. The majority of shots

originated from a passing car. Thirteen percent of upper extremity

wounds were associated with a vascular injury, and a vascular injury

was four times more likely when the patient had a “major” fracture

versus a “minor” or no fracture (50).

Charlotte, NC, reviewed 218 gunshot fractures from 1985 to 1989. Male

victims again predominated at 91%, 79% were uninsured, and 65% could be

connected with the use of illicit drugs; medical charges averaged

$13,108 (27). Another Los Angeles study

reviewed gunshot wounds to the hands specifically, with 91 wounds

representing 78 men and 13 women. Multiple injuries were present in 56

(58.2%), and 11% involved shotguns. The authors noted a greater injury

with hollow point, fluid-filled, or partially jacketed bullets even in

the setting of lower velocity (54). Further

experience at the Martin Luther King, Jr., General Hospital in Los

Angeles catalogued 387 children who sustained gunshot wounds, 117 of

whom suffered extremity wounds (70). Finally,

at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta, of 72 gunshot wounds, the most

consistent region involved was the hand and wrist (34).

wounds (GSW) of the hand based on the experience at the Martin Luther

King, Jr., General Hospital in Los Angeles (Table 45.2) (54).

|

|

Table 45.2. Classification of GSWs to the Hand

|

-

Adhere to the principles of advanced

trauma life support. More than half of gunshot wounds to the hand are

associated with multiple gunshot injuries (54).

In Ogden’s study of extremity gunshot wounds, 6% of through-and-through

extremity wounds were associated with missile penetration of another

“major” body area. Do not allow the obvious hand injury to distract

from diagnosing a possibly life-threatening occult wound. Disrobe the

patient and inspect all surfaces, including the back. -

Begin specific examination of the wounded

upper extremity with assessment of entrance and exit wounds, their size

and character, swelling and deformity in the region between, and a

mental note of vital structures potentially involved in the path of the

bullet. -

Check pulses and circulation by Allen’s

test. With the high collateral flow in the distal upper extremity, the

mere presence of pulses does not rule out a significant vascular injury

proximally. Avoid tourniquets for control of brisk bleeding; rather,

apply direct pressure. Resist the urge to clamp or coagulate blindly,

as future vascular and nerve repair will likely be compromised by

inadvertent injury to underlying structures. If an extremity wound is

ever fatal, it is most likely related to initial blood loss (64). -

Perform a neurologic examination

documenting the function in the radial, median, and ulnar nerves.

Document profundus and superficialis tendon function as well as the

bony architecture of the hand. -

Following examination, gently rinse with saline solution and apply a moist saline dressing and splint as appropriate.

-

Administer intravenous first-generation cephalosporin or ceftriaxone.

-

Give a tetanus booster in patients with

known active immunity and tetanus toxoid plus human recombinant

antitoxin to the nonimmunized, according to the guidelines of the

Committee on Trauma of the American College of Surgeons. -

Bullet sterilization from the heat of firing was disproven in 1892 (18).

The bullet will carry bacteria from the body surface and any other

tissue through which it passes (such as colon). The most important

cause of death from missile wounds on the battlefield in the

preantibiotic era was streptococcal bacteremia, not clostridial

myositis (19). -

Treatment of low-velocity gunshot wounds

following emergency room treatment is controversial, with

recommendations ranging from a minimum of 24 to 48 h coverage with IV

cephalosporin to oral antibiotics given to outpatients only after

manifestation of signs and symptoms of infection (29,34,50,70).

Marcus advises that “the judgment of the physician performing the

initial examination is the most important factor determining the

appropriate treatment of a gunshot wound”(42). See the discussion that follows on surgical indications. -

Radiographically image the entire

involved extremity and do a chest radiograph as well. Complex

associated fractures may then be further imaged using CT, especially

with involvement of the carpus. -

Do not overlook compartment syndrome,

other associated gunshot wounds, and missile emboli. Suspect

compartment syndrome of the hand when the hand is swollen. This

presentation may be confused by associated skeletal and nerve injury.

The hand will almost invariably be held in an intrinsics minus

position. Naidu and Heppenstall find that excruciating pain with

passive motion of the MCP joint of the involved digit is the most

sensitive clinical indicator (49). -

Measure intracompartmental pressures.

Recommendations for fasciotomy vary, ranging from intracompartmental

pressures of over 30 mm Hg up to pressures within 30 mm Hg of the

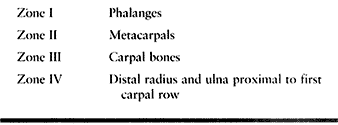

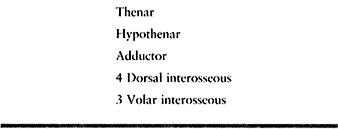

diastolic systemic pressure (26,52). There are 10 separate compartments in the hand (Table 45.3).

Most frequently, release is necessary of one or two dorsal

compartments, the hypothenar, and the thenar, with release of the

transverse carpal ligament. The finger is enclosed in a tight investing

fascia supported by unyielding volar skin. Occasionally midaxial finger

incisions are also required to avoid tissue loss (49,52). The reader is referred to Chapter 13 and Chapter 65 for further discussion of compartment syndromes in the upper extremity. Table 45.3. Compartments of the Hand

Table 45.3. Compartments of the Hand -

Missile emboli most frequently occur with

close-range shotgun injuries. They should be suspected when the primary

wound cannot account for peripheral ischemia. Embolization has also

been reported with 22-caliber missiles; the energy of the bullet is

spent entering the vessel, and it is then swept along in the flow of

blood until the lumen size limits further travel. Reported distant

emboli sites include the posterior tibial artery, middle cerebral

artery, popliteal artery, femoral artery, anterior tibial artery, and

the ulnar artery (5,73).

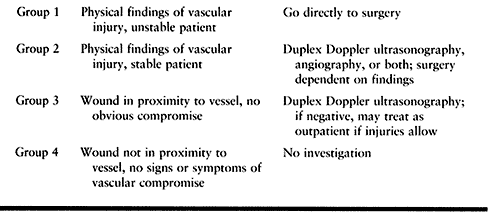

In addition, multiple wounds in the same extremity and potential

arterial compromise may merit arteriography if the condition of the

patient allows, to better plan the surgical approach and intervention.

|

|

Table 45.4. Ordog’s Indications for Vascular Imaging

|

determined by the severity of the injury. Very often, little

information is available regarding the type of weapon, the

range

at which the injury occurred, or the specific ammunition used. The

treating physician must base a reasonable decision not on conjecture as

to the velocity of the bullet but on the characteristics of the wound

under examination. As previously mentioned, it is possible to have

small entrance and exit wounds in the presence of massive underlying

soft tissue and bony destruction. This is evidenced by massive

swelling, loss of bone stability, and neurologic and vascular deficits,

which require emergent surgery. Small entrance and exit wounds in the

absence of these clinical signs may, in contrast, be treated with

simple wound cleansing and dressing on an outpatient basis. Hampton’s

review of 368 bullet wounds of the extremities, more than half of which

had associated fracture, showed that over 300 did not require

debridement, and no sepsis resulted (28).

wounds of the extremities and grouped them on the basis of both

debridement technique and presence or absence of fracture. Nonoperative

treatment was defined as excision of wound margins under local

anesthesia in the emergency room and wound irrigation with saline, with

or without antibiotics. He found no difference in outcomes between

those treated with surgical debridement and antibiotics and those

without aggressive treatment (42).

When they are lodged in the hand, their mere size may necessitate

removal. When retained around joints or joint areas where exposure to

synovial fluid and abrasion is possible, excision is also recommended

to avoid mechanical damage as well as lead arthropathy (23).

When they are lodged in the physis of a child, removal is mandatory.

Washington and Lee reviewed their experience with gunshot wounds in

children and reported that all physeal arrests were easily predicted on

the admission radiographs (70). It was

previously thought that the physis was highly susceptible to

high-velocity injury if the track of the bullet was nearby.

exploration in and of itself, as many are neurapraxias. Phillips

recommends no exploration before 3 months, then electrical studies to

establish the need for repair or grafting (54).

-

Acute debridement serves two purposes: to

remove nonviable tissue and foreign debris, and to decompress the

wounded hand. With the close juxtaposition of many crucial structures

in the hand, when there is any doubt about the viability of an

important structure, delay excision until the second debridement. -

Debride skin conservatively with little or no excision of skin (31). Extend small wounds for adequate exposure of injured structures.

-

Bony fragments may be retained, even if detached, unless grossly contaminated.

-

There is rarely a good argument to be

made for primary closure of wounds following the initial debridement.

Sherman studied shotgun wounds and their complications and found that

31% of wounds primarily closed following debridement required further

operative care for infection (61). -

Manage wounds open with moist dressings and splints.

-

Carry out a second debridement 48 to 72 h

following the first. Debridement is a learned art, as emphasized by

Brown, who recommends: “Don’t get wounded in the first 2 months of the

war” (11). -

Complete or near amputations of the hand

or digits rarely are appropriate for replantation. Salvage of skin,

tendons, bone, nerve tissue, and even digits themselves

P.1440

may

be valuable in reconstruction of the remainder of the injured limb. The

viable skin covering near-amputations may be valuable in skin coverage. -

Skeletal stability is crucial for soft

tissue healing as well as for mobilization of the hand to hasten

rehabilitation. Restore both the longitudinal and transverse arches of

the hand, even at the time of the initial debridement. In cases of bony

loss, use Kirschner wire bayonet spacers, cross-pinning of metacarpals,

or external fixation to achieve stability pending secondary bony

reconstruction. -

Nerve repair in the hand may be carried

out at the time of initial or secondary debridement, or the nerve ends

may be marked for later repair or grafting. Stein and Strauss recommend

primary repair only in cases of clean transection, whereas Hennessy

advocates primary repair whenever possible, using nerves from nonviable

parts of the injured hand when available (31,64). -

When vascular repair is necessary, gain

control of the injured vessel both proximally and distally with

adequate exposure. In the repair of the radial or ulnar artery in the

distal forearm following a close-range shotgun wound, use caution to

avoid peripheral embolization of pellets. Vascular repair almost always

will require segmental resection, as the zone of injury often extends

beyond the area visibly damaged. Vein grafting is usually necessary (5,26,32,50,61,64,73). -

Skin coverage options after the final

debridement include delayed primary closure, healing by secondary

intent, local flaps, or distant flaps. -

Postoperatively, support the wounded

tissues with a dressing firm enough to eliminate dead spaces without

inhibiting venous return. The dressing absorbs blood and exudates,

provides a barrier to further contamination, increases patient comfort,

and facilitates mobilization of uninjured parts. Place the hand in an

intrinsics-plus position unless that compromises the repairs. Elevate

the limb and begin early range-of-motion exercise for the shoulder and

elbow to avoid stiffness.

understanding of his role and responsibility as an active member of the

rehabilitation team. Begin patient education after application of the

first postoperative dressing or in the emergency room for those treated

nonoperatively. Mobilization of all parts possible, edema control,

wound care, and splinting in functional positions are all elements of

success in returning the injured limb to useful function.

associated gunshot wounds, underestimated vascular injury, and peri- or

intraarticular lead particles. Lead near or in joints will be dissolved

over time by acidic synovial fluid and incite a proliferative

synovitis, which may result in focal articular cartilage erosion and

degenerative arthritis. Radiographically, lead may resemble

chondrocalcinosis, with metallic not calcific deposits. Remove

intraarticular lead particles soon after injury. If lead arthropathy is

suspected, measure serum lead levels. Delay surgical procedures until

levels have been reduced with chelating agents such as D-penicillamine (23).

impairment following low-velocity gunshot wounds to the hand was loss

of motion secondary to fractures and joint disruption, and this

surpassed the disability from infection and tendon, nerve, or vascular

injury. Most marked losses involved the proximal interphalangeal (PIP)

joint. They strongly recommend stable internal fixation with early

mobilization (16).

the hand is to treat individually each wound rather than mindlessly

following protocols established for high- versus low-velocity weapons.

impact associated with these injuries. Sensitivity to these issues and

cooperation with counselors, social workers, and others can strongly

influence the final outcome.

rollers will produce a true crush injury. Such trauma usually occurs in

the workplace from a printing press or with a home laundry machine—the

classic “wringer arm” (43). The nature of the

damage and the severity of the wound produced by these wringers or

rollers are determined by a number of factors (17,60).

Important ones include clearance between the rollers, the type of

surface (steel or rubber), and the temperature of the crushing device.

The speed of the roller partially determines the force applied; skin

avulsion occurs at higher speeds.

is created when the large extremity is propelled into the small gap

between the rollers. Compression results in tissue contusion. A friction abrasion force characteristically produces a distally based flap and often tears the skin. Last, a shearing force moves the soft tissues over deeper fixed structures, resulting in lacerations,

subcutaneous hematomas, and disruption of musculotendinous junctions.

The degree of injury is related to the roller size, clearance, duration

of compression, and the method of extraction. The severity and depth of

injury produced by the compression and shearing forces may not be

readily evident. Skin that has been completely removed from its blood

supply will undergo necrosis (67).

Hemorrhage may further separate the subcutaneous tissues from the deep

fascia and require drainage. Swelling or bleeding beneath the forearm

fascia can produce increased pressure (see Chapter 13 and Chapter 65)

and muscle ischemia and result in Volkmann’s contracture. Although this

is often described in the forearm, ischemic contracture involving the

intrinsic muscles can occur in the hand (51).

When examining the severely crushed, edematous hand, if pain is

produced by the intrinsic stretch test and compartment pressures are

significantly elevated, perform decompression of the interossei. If

peripheral circulation is impaired and/or distal pulses are not

palpable, evaluate further with a Doppler device and do an arteriogram

if necessary. Test sensibility: two-point discrimination values greater

than 10 mm are suggestive of nerve compression but may represent a

traction injury to a nerve. Because fractures occur in 25% of roller

injuries, obtain appropriate radiographs (43).

An injury that is frequently unrecognized is dislocation of the

metacarpal trapezial joint. This occurs when the transverse arch of the

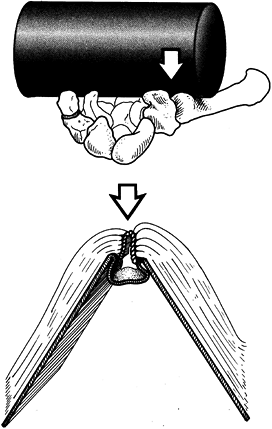

hand is flattened and compressed (Fig. 45.1) (71).

|

|

Figure 45.1. Roller or crush injuries extending to the level of the wrist (A) can dislocate the basal (trapezial–metacarpal) joint and (B) are similar to breaking the binding of a book.

|

household laundry wringer were once common occurrences; fortunately,

this device has almost disappeared with the advent of modern clothes

dryers, and such injuries are now rare. Wringer injuries usually occur

in children younger than 15 years of age and most often between ages 3

and 5 years. The maximal injury is usually located at the area most

proximally involved (45). Damage usually occurs

up to the level of the elbow, with more proximal trauma occurring in

younger patients. The most frequent injuries encountered are friction

burns from abrasion and soft tissue contusion, which can occasionally

lead to tissue necrosis. Lacerations, joint injuries, and vascular

trauma occur less frequently (65).

-

Cleanse the entire limb.

-

Reduce dislocations and fractures.

-

Suture lacerations.

-

Open wound care may be appropriate, particularly with marginally perfused skin flaps.

-

Apply a light nonconstrictive dressing

and splint. The rare patient with a limb-threatening vascular injury or

a major soft-tissue injury requires prompt surgical treatment. As with

other crush injuries, the greatest difficulty is in assessing the

initial depth of a wringer injury in a child. The most common surgical

procedure required after a wringer injury is skin grafting. Antibiotics

are indicated in patients with open fractures or obviously contaminated

wounds (25).

-

Prepare and drape the entire extremity.

-

Do not use a tourniquet.

-

Do a methodical layer-by-layer debridement and irrigation of open wounds.

-

If a compartment syndrome is present in the hand, wrist, or forearm, perform appropriate fasciotomies (15,49,51).

Decompressions of the hand often require dorsal incisions for the

interossei and separate incisions for the hypothenar and thenar

compartments. For decompressions of the hand and/or forearm, include a

carpal tunnel release. -

Nerve injuries are difficult to assess,

as loss of function most commonly results from a neuropraxia, but

direct crushing and traction injury may be present (66).

If the nerves are visible in wounds or fasciotomy incisions, inspect

them; otherwise, simply observe them as they recover without surgical

intervention. -

Stabilize fractures, as this enhances soft tissue management and facilitates rehabilitation.

-

Repair tendon lacerations or avulsions.

-

Leave all wounds open at the time of

initial debridement. A common injury is a palmar laceration with a

distally based skin flap and crush of the thenar and hypothenar

muscles. Further necrosis may occur, requiring serial debridements. -

Cover the wounds with moist dressings and

splint the extremity with the wrist in extension, the MP joints flexed,

and the interphalangeal joints extended. -

Return to the operating room at 36- to 72-h intervals or as often as necessary to complete debridement of nonviable tissue.

-

Skin loss will require resurfacing with either grafts or flaps (9,36,39).

-

Crush injuries involving the dorsum of

the hand usually have damage to skin, extensor tendons, and bone and

joints. Conventional treatment of these injuries has been with staged

reconstruction, first obtaining soft-tissue coverage and then

performing bone repair and tendon grafts. Recent studies have suggested

that immediate reconstruction with primary tendon and bone grafting

along with skin closure results in faster return of motion and fewer

surgical procedures. -

Injuries that involve both surfaces of the hand frequently result in amputation of some portion.

immediately following surgery. While the surgical dressing immobilizes

the injured tissues in the appropriate position, move the uninvolved

portions of the hand. After the wound has stabilized, direct a more

vigorous mobilization program at overcoming the most common problems of

chronic edema and stiff joints (72).

elevation and active motion. Retrograde massage may prove helpful, and

thermoelastic gloves can provide continual compression and warmth. To

prevent joint stiffness and contractures, promptly mobilize all joints

within the limits of pain tolerance. Try to move each joint through as

great an arc of motion as possible at least three times a day, and

preferably once each hour. With further healing, and when the patient

has less pain, dynamic splinting may be added to the exercise program.

Although splinting of the hand in metacarpophalangeal joint flexion and

interphalangeal joint extension (safe position) prevents the most

serious joint contractures, this attitude of the fingers increases the

chance of developing contracture of the intrinsic muscles. Persistent

dorsal edema of the hand predisposes to intrinsic muscle contracture

even if these muscles have not been compromised initially. An intrinsic

stretching exercise program can prevent contracture.

also restores the gliding of tendons and increases both tendon strength

and wound healing. Motion begun too early may sometimes compromise

soft-tissue healing; therefore, carefully monitor the patient.

Persistent drainage from a wound indicates inadequate debridement with

the presence of necrotic tissue or retained foreign material.

scar contractures, tendon adherence, nerve compression, and chronic

pain (12). The blood supply to skin flaps that

have been markedly contused is usually poor and often distally based.

Excise all obviously nonviable skin primarily. Suture borderline tissue

flaps without tension and carefully observe them. By 3 to 5 days after

injury, tissue viability should be clarified, and the wound can be

debrided of all necrotic material.

simplest techniques that will provide a satisfactory result, such as a

skin graft, either split thickness or full thickness. A local flap can

be used to cover a small full-thickness defect resulting in exposed

bone or tendon that requires vascularized tissue. More proximal flaps

from the arm (posterior interosseous artery or radial forearm) can be

employed for coverage of larger defects. More distant flaps (abdominal

or groin) and free tissue transfers should also be considered. The

latter may be composed of skin, muscle, fascia, or composite tissues.

Although detached skin may be defatted and used as a full-thickness

skin graft, if it is severely traumatized it will fail to heal. The

decision as to which coverage is most appropriate depends on the

requirements of future reconstructive surgery.

skin grafting or with a surgical incision required for a fasciotomy.

Prevention of the latter can be achieved by application of the

principles for incision placement (40). Contracted skin grafts can be resected and the defect treated with local soft-tissue mobilization or tissue expansion (47).

A graft may be replaced by a flap if additional tissue is required

after the contracture is released. This is important if the location is

one that will receive considerable pressure with use or that will be

subject to tissue breakdown. For example, split-thickness skin grafting

on the palm may not withstand normal shearing forces, and primary

closure of a wound involving a flexion crease ultimately worsens the

contracture. Occasionally contractures can be released with a Z-plasty or a local flap.

considered after a crush injury, direct muscle trauma with necrosis and

fibrosis is more common. Selective muscle debridement is part of

treating an open injury. Although adherence of injured muscles or

tendons is common, prompt remobilization can limit the loss of motion

in the

hand.

However, fractures and joint injuries will compound the problem.

Tenolysis should be considered only after all the tissues in the

extremity are well healed and the patient obtains full passive motion

in the fingers. Adherence proximal to the musculotendinous junction

will not respond to a lysis and should not be attempted, as it will not

improve distal motion.

injury. External compression can occur at the site where a nerve passes

adjacent to traumatized muscle or injured fixed tissues, that is,

ligaments or bone. Crushing trauma is even more likely to produce an

intraneural injury. The question is whether there is external nerve

compression or internal fibrosis of the nerve. The production of

paresthesias on percussion over a nerve may localize the injury but

will not clarify the diagnosis. Electromyelograms and nerve conduction

studies may help differentiate external or internal compression from

traction.

Several weeks after the initial trauma, the patient should be able to

control pain with a nonnarcotic medication. If the patient still has

considerable pain after this, a chronic problem must be acknowledged

and will require the combined efforts of several specialties. If the

patient is to participate actively in an exercise program, pain must be

controlled. Supportive splinting and a variety of modalities including

transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulator are indicated. The

possibility of the patient developing a chronic pain syndrome must be

recognized from the onset. Successful treatment requires early

recognition and a rapid response.

the hand alone, they need to be considered in light of the broader

classification of mutilating hand injuries. This is a topic too large

to be included in this chapter, but a few principles need to be

understood. Reconstructive surgery after a mutilating wound will be

more effective if the primary treatment minimizes the amount of scar

tissue. Soft-tissue coverage is critical. The preservation or sacrifice

of tissue must be designed to gain the greatest function at the least

risk. When the hand has been mutilated, normal function may be an

unrealistic expectation in the setting of anatomic loss, but useful

function may be created with what remains. Microsurgical techniques

have expanded the repertoire of the reconstructive surgeon.

recognize the depth and significance of the original injury. The most

critical element after such an injury is the correct timing of

treatment. The judgment required to make these critical decisions

arises from knowledge and experience.

caused by grease, paint, or paint thinner occur frequently. Although

the wound may initially appear innocuous, these injuries are surgical

emergencies that require prompt exploration, decompression, and

debridement (41).

The substance fired at such velocity through a small nozzle enters the

skin and spreads along fascial planes, tendon sheaths, or neurovascular

bundles—the paths of least resistance (35).

Tissue within the hand may be mechanically damaged by pressure and

rendered ischemic. In addition, the material injected produces an acute

chemical inflammation, which may be associated with additional soft

tissue and vascular damage (14).

is not completely removed, chronic inflammation, fibrosis, foreign body

granuloma (oleomas), and sinus formation with chronic tissue breakdown

may occur. Paint produces an acute inflammatory response, whereas

grease causes a delayed chemical reaction resulting in fibrosis and

stiffness. The volume of material that enters the hand is directly

proportional to the pressure produced by the gun. The greater the

volume of material that has been injected, the greater is the amount of

soft tissue damage that occurs.

minimal, with only a burning discomfort at the injection site. Within a

short time, the finger usually becomes distended, pale, and numb with

throbbing pain. Subsequently, greater pain and mottling of the skin

appear. The pain may be related to ischemia, the injection having

created a compartment syndrome of the digit. If a considerable volume

of material has been injected, enlargement of the finger is immediate.

The left hand is involved more frequently than the right, and the

patients are usually men. Common injection sites include the distal

segment of the index finger, thumb, or middle finger, which are usually

used to check a presumed “plugged” injection tip. The palm and other

digits are damaged less frequently.

demonstrate how deeply the grease or paint has extended. Many greases

are radiopaque because of the lead that has been added as a lubricating

agent. If routine x-rays do not yield enough information,

xeroradiographs may provide useful information. Patients can develop

systemic effects, which include fever, lymphangitis, and an elevated

leukocyte count. These signs usually appear within 2 days after the

injury and may last 4 to 5 days (13).

-

High-pressure injection injuries require immediate surgery.

-

Local anesthetic blocks in the palm are

usually contraindicated, and the extremities should obviously not be

wrapped with a pressure bandage before application of the tourniquet (35). -

Use a modified midlateral incision to

explore the finger. A zig-zag approach, although providing better

exposure, is more likely to result in skin slough and may lead to

further tissue compromise in wounds left open for subsequent

debridement. If necessary, continue the incision into the palm in a

curvilinear fashion, extending it past the wrist and into the forearm

if needed. -

After surgical exposure, remove all the

abnormal material such as grease or paint. Excise any fat or fascia

that is involved. Resect tendon sheaths in part if they are involved,

taking care to leave essential portions of the fibro-osseous sheath

system. A small curet or rongeur may be helpful in removing the

material. -

Nerves and arteries that are functional but have the foreign substance embedded in them should be left intact and not resected.

-

Even after a meticulous dissection, some

foreign material may remain. Solvents for grease or paint are

inefficient and are not employed for fear of causing more tissue

damage. Pack open the wounds with the intention of performing a

secondary exploration and closure in 2 to 3 days. -

An alternative choice is to close the wounds loosely over drains.

-

A third choice is to leave the wound

completely open, allowing it to heal by secondary intention. Skin

grafts may be required to close wounds if critical structures are

exposed. -

Perform wound cultures at the time of all

surgeries, as infections are not infrequent. Many surgeons recommend

antibiotic coverage for 2 weeks, but the use of prophylactic

antimicrobial drugs is not clearly indicated unless there is an active

infection (41). -

Immobilize the hand in a safe position (MP flexion and interphalangeal joint extension).

healing by secondary intention with early motion and whirlpools as well

as an intensive active exercise program. Patients whose wounds have

been packed open should be considered for the same treatment or have

their wounds reevaluated in the operating room for redebridement in 2

to 3 days. When it has been determined that all the foreign material

has been removed, involve the patient promptly in the remobilization

program as mentioned above. Make no attempt to close small defects with

skin grafts. Except during exercise, place the patient’s hand at rest

in a position to prevent contractures, particularly flexion

contractures at the PIP joint. Eventual impairment is related to the

amount of tissue destroyed by foreign material. Paint gun injuries

generally inflict greater damage than do grease guns, and injections

into the palm have a better prognosis than injury to the digits.

result from failure to debride the wound sufficiently and premature

wound closure. Although much has been written about the toxicity of

both grease and paint, injected paint thinner is the most difficult to

detect and completely remove (63). Injuries from paint thinner should never be closed primarily; multiple debridements and reexplorations can be anticipated.

result often occurs because the patient or physician initially

evaluating the injury is unaware of its significance (22).

In one recent series, the only patients requiring amputation were those

initially evaluated 3 to 8 days following injury. Although prompt

surgery is recommended, this alone does not always ensure a good

result. It is also possible to obtain a satisfactory result when

surgical treatment has been delayed, particularly with grease gun

injuries (62).

patient initially and remain under consideration should delayed healing

or complications arise. Retention of the tip of a digit that has

required extensive soft-tissue and skin resection is not beneficial.

The patient will be left with a painful atrophic finger with little

function. The period of disability can be extensive, and it averaged 7

months in one study (22). In a more recent

study where patients were treated with open wound management (wide

debridement, drainage, open packing, and delayed closure), all the

patients returned to work, 92% to their previous job (55).

Because of the possible prolonged morbidity, several authors have

recommended early amputation, especially after a paint gun injury (35,57). Prompt amputation often allows the patient to return to work within 6 to 8 weeks of the injury.

breakdown, ulceration, and sinus formation with discharge of foreign

material. Delayed infection rarely occurs if one can obtain wound

healing within 2 weeks of the original injury. However, retention of

foreign material, necrotic tissue, and chronically open wounds can

produce sepsis.

casualties in the 1982 Falkland Islands conflict were related to

frostbite. Unfortunately, frostbite is also a civilian concern, even in

urban, populated areas today. The human body is equipped with many

mechanisms for the dissipation of heat but must rely on largely

conscious measures for heat conservation. The strongest human defense

against frostbite is the conscious decision to wear adequate clothing

and seek shelter. Not surprisingly, then, urban frostbite most commonly

occurs in those with altered mental states such as psychiatric illness

and substance abuse. The homeless, elderly, and children are also at

risk.

Wind velocity, ambient temperature, altitude, and duration of exposure

set the environmental stage, acting on host factors such as protective

clothing, systemic and vascular disease, previous cold injury, and

ability to seek adequate shelter and treatment.

|

|

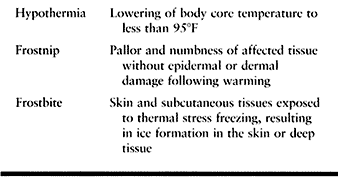

Table 45.5. Differentiation of Cold Injuries

|

frostbite injuries in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, concluded, “Fit,

well-prepared people without cerebral impairment rarely present with

significant frostbite injury” (69). In this

series, 78% of victims were male and 46% associated with alcohol

consumption, 17% with psychiatric illness, and 19% with trauma. The

distribution of injury was 19% upper extremity, 31% upper and lower,

and 47% lower extremity. Of the 63 patients with upper extremity

frostbite, 13 required major amputation and 18 minor (69).

frostbite cases at Cook County Hospital in urban Chicago were reported

over 10 winters. The mean age of the patients was 43 years, with over

76% between the ages of 30 and 60. Upper extremity involvement (47%)

was slightly less than lower extremity (53%). Children showed almost

exclusively upper extremity involvement, many with bilateral

“glove-like” lesions. Hand amputations, when required, were most common

at the finger MCP joint and the thumb IP joint (7).

predictors of poor outcome such as major tissue loss. Strong

association was found with impaired cerebral function (alcohol,

psychiatric illness), lower extremity involvement, infection on

presentation, and delay in seeking medical attention (68).

Inadequate protective clothing and exposure to metal or wetness was

also correlated with severity of injury by Knize in a Denver, Colorado

study (37).

cold environment. The spinal cord signals the hypothalamus, resulting

in increased muscle tone (shivering) and release of catecholamines and

thyroxine. Increase in basal metabolic rate, vasoconstriction, and

decreased sweating result. The most important organ in temperature

regulation is the skin, specifically that of the extremities, which

represents more than 50% of total body surface area. Blood flow to the

skin during cold stress can virtually cease or can increase as much as

200-fold for heat loss (8). The “hunting

reaction,” described by Sir Thomas Lewis in 1830, preserves both core

temperature and extremity viability during cold exposure by cyclically

alternating vasoconstriction and vasodilation to the limbs (8,48,56).

This regulatory mechanism ceases when the core temperature drops,

prioritizing preservation of core temperature over extremity viability.

of tissue. Slow freezing results in extracellular ice crystal

formation, which increases the osmotic pressure of the interstitium,

pulling out intracellular water. Intracellular fluid does not

crystallize, as it is continuously lost with a corresponding reduction

of freezing point (48). Cell membrane damage,

most marked in endothelium, occurs by mechanical damage from crystals

and dramatic osmotic changes. Endothelial cell injury is seen

microscopically with separation from the internal elastic lamina of the

arterial wall. Ice crystal formation in plasma resulting in red cell

sludging further compromises circulation. Cartilage cells, especially

in epiphyseal cartilage, are very susceptible to even brief freezing.

Muscle, blood vessels, and nerves are damaged more quickly than bone

and connective tissue (8,48,56).

10°C/min. This results in immediate cell death by intra- and

extracellular crystal formation. Exposure to cold metal or volatile

liquids is the most common mechanism.

and damaged endothelial-lined capillaries dilate and leak fluid and

protein into the interstitium. Intracellular swelling occurs in any

viable cells, as they were previously dehydrated and regain water lost.

Red and white blood cells and platelets aggregate, contributing to

microcirculatory failure, a significant cause of tissue loss (8,48). Continued

tissue injury following reperfusion may also be related to prostaglandin-induced vasoconstriction (PGF2α, thromboxane A2),

similar to factors found in burn injury. These factors have been found

in significant concentration in clear blisters associated with

frostbite, leading some to recommend their debridement to limit further

loss of viable tissue. Aloe vera is an inhibitor of thromboxane A2, and aspirin or ibuprofen controls prostanoid production (30,44).

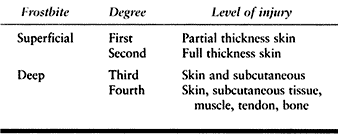

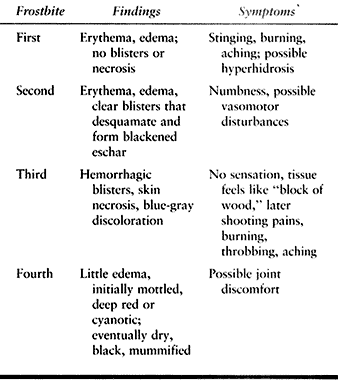

burn injury and indicates level of tissue loss. The prediction of level

is often less than accurate, leading some to recommend a simplified

version indicating only superficial and deep. Table 45.6 demonstrates both systems. Table 45.7 coordinates clinical presentation with degree of injury.

|

|

Table 45.6. Classification of Frostbite by Level of Tissue Loss

|

|

|

Table 45.7. Classification of Frostbite by Clinical Presentation

|

protection of the injured part from mechanical trauma, avoiding

pressure, rubbing, or exercise. If there exists any possibility of

further cold exposure, rewarming is strongly contraindicated.

Refreezing results in much greater tissue necrosis than the persistence

of freezing until definitive and controlled rewarming can occur.

Salimi, in a rabbit foot model, demonstrated that rapid rewarming was

effective in limiting necrosis only when performed immediately after

freezing. He recommends it only if it is performed immediately

following removal from freezing (58).

Unfortunately, most patients’ injuries have already spontaneously

thawed on presentation, 88% in the large Chicago Cook County Study (7).

40°C to 42°C water containing a mild antibacterial agent until a

flushed appearance to the part indicates reperfusion. Continuous

monitoring of water temperature is imperative. Dry rewarming is

contraindicated to avoid risk of burn injury. Narcotic analgesics will

be required during rewarming. Give tetanus booster and antitoxin if not

up to date. Obviously, if hypothermia exists, systemic treatment and

measures take priority over rapid rewarming, although they often may be

instituted simultaneously. Antibiotic prophylaxis is controversial and

likely appropriate only in severe cases with delayed presentation.

edema. Debride clear blisters but leave hemorrhagic blisters

undisturbed. The goals of wound care are to preserve viable tissue and

to prevent infection. Whirlpool treatment is recommended for open

wounds. Escharotomy and fasciotomy may occasionally be required.

Dressing wounds with topical agents such as aloe vera may be helpful in

counteracting the vasoconstrictive effects of thromboxane A2, and oral aspirin or ibuprofen counteracts the effects of prostanoids (30,44).

Systemic vasoconstrictive agents such as nicotine are obviously

prohibited. Multiple other treatments have been studied, but their

usefulness has not been established; these include dextran, heparin,

pluronic F-68, hyperbaric oxygen, phenformin ethylestrenol,

streptokinase, urokinase, and reserpine. Hyperbaric oxygen is not

helpful and may cause vasoconstriction and reduction in blood flow (56).

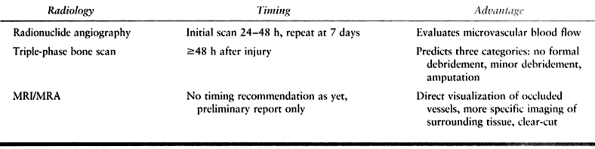

and wait before you ablate” characterize the historical treatment of

frostbite. Difficulty in prediction of tissue loss has led to a very

conservative approach, often awaiting autoamputation. Earlier

prediction is now possible through triple-phase bone scanning,

radionuclide angiography, and magnetic resonance imaging/MRA (Table 45.8).

|

|

Table 45.8. Imaging for Frostbite

|

guillotine fashion, with delayed closure or coverage. Acute amputation

is necessary only in the setting of infection, most common in patients

with a delayed presentation.

surgically. Reserpine infusion intraarterially into the affected limb

causes depletion of arterial wall norepinephrine for up to 2 to 4 weeks

(56); however, no difference has been shown in

conservation of tissue, edema resolution, pain reduction, or improved

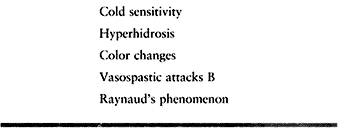

function. Surgical sympathectomy plays a delayed role in treatment of

vasospastic syndromes following a cold injury.

hands without digits or loss of all but the proximal thumb.

Reconstruction of this difficult problem is possible through tissue

transfers and free flaps. An excellent report of 25 digitless hand

reconstructions by Borovikov demonstrated a reliable technique of

toe-to-hand transfers to regain opposition (6).

Intrinsic injury affects strength and fine motor control in relation to

both direct muscle freezing and neurologic injury. Arvesen studied 40

Norwegian soldiers following local cold injuries. Nerve conduction

velocities were still markedly decreased 3 to 4 years following injury

to the nerves in previously cold-injured limbs, even proximal to the

level of injury (2).

|

|

Table 45.9. Vasospastic Symptoms

|

and the destruction of articular cartilage by ice crystal formation

explain the arthritis that can occur as early as months following

injury. In children, both the physis and the epiphysis are susceptible.

Classic radiographic findings in the juvenile frostbite injury include

total absence of the distal phalangeal epiphysis and damage to the

middle phalangeal epiphyses. Distal metaphyses are frequently irregular

even in the absence of clinical frostbite (56).

of previous cold injuries, 20 to 30 years following injury, similar to

burns or chronic osteomyelitis.

improving the outcome of frostbite injury is its prevention. The

important role of inflammatory mediators in perpetuating tissue damage

following cold injury will be a future focus of research to modulate

this effect. Acute management must focus on the basic principle of

doing no further harm and protecting viable tissue. Rapid rewarming may

be of great benefit only when a patient presents with frozen tissue.

Later reconstruction must be tailored to the unique

needs of the injured individual, often requiring tissue transfer.

scheme: *, classic article; #, review article; !, basic research

article; and +, clinical results/outcome study.

F, Johs SM, Leighton TA, Klein SR. Peripheral Arterial Shotgun Missile

Emboli: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Management—Case Reports. J Trauma 1991;31:1426.

GT, Fisher JC, Edgerton MT. “Wringer Arm” Re-evaluated: A Survey of

Current Surgical Management of Upper Extremity Compression Injuries. Ann Surg 1973;177:362.

KK, Weaver LD, Todd AO, et al. Efficacy of Ceftriaxone versus Cefazolin

in the Prophylactic Management of Extra-articular Cortical Violation of

Bone Due to Low-Velocity Gunshot Wounds. Orthop Clin North Am 1995;26:9.

WB, Dustman JA. Preservation of Functional Following Complete Degloving

Injuries to the Hand: Use of Simultaneous Groin Flap. Random Abdominal

Flap and Partial-Thickness Skin Graft. J Hand Surg 1981;6:82.

GJ, Balasubramanium S, Wasserberger J, et al. Extremity Gunshot Wounds:

Part One—Identification and Treatment of Patients at High Risk of

Vascular Injury. J Trauma 1994;36:358.

P, Hansraj KK, Cox EE, Ashley EM. Gunshot Wounds to the Hand. The

Martin Luther King, Jr., General Hospital Experience. Orthop Clin North Am 1995;26:95.

MR, Turkula-Pinto LD, Cooney WP, et al. High-Pressure Injection

Injuries of the Hand: Review of 25 Patients Managed by Open Wound

Technique. J Hand Surg 1993;18A:125.