Femoral Shaft

Authors: Koval, Kenneth J.; Zuckerman, Joseph D.

Title: Handbook of Fractures, 3rd Edition

Copyright ©2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > IV – Lower Extremity Fractures and Dislocations > 32 – Femoral Shaft

32

Femoral Shaft

-

A femoral shaft fracture is a fracture of

the femoral diaphysis occurring between 5 cm distal to the lesser

trochanter and 5 cm proximal to the adductor tubercle.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

-

There is an age- and gender-related bimodal distribution of fractures.

-

Femoral shaft fractures occur most frequently in young men after high-energy trauma and elderly women after a low-energy fall.

ANATOMY

-

The femur is the largest tubular bone in

the body and is surrounded by the largest mass of muscle. An important

feature of the femoral shaft is its anterior bow. -

The medial cortex is under compression, whereas the lateral cortex is under tension.

-

The isthmus of the femur is the region

with the smallest intramedullary (IM) diameter; the diameter of the

isthmus affects the size of the IM nail that can be inserted into the

femoral shaft. -

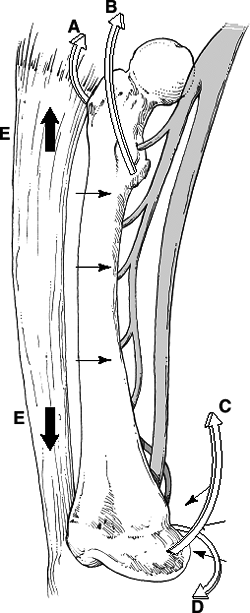

The femoral shaft is subjected to major muscular deforming forces (Fig. 32.1):

-

Abductors (gluteus medius and minimus):

They insert on the greater trochanter and abduct the proximal femur

following subtrochanteric and proximal shaft fractures. -

Iliopsoas: It flexes and externally rotates the proximal fragment by its attachment to the lesser trochanter.

-

Adductors: They span most shaft fractures

and exert a strong axial and varus load to the bone by traction on the

distal fragment. -

Gastrocnemius: It acts on distal shaft fractures and supracondylar fractures by flexing the distal fragment.

-

Fascia lata: It acts as a tension band by resisting the medial angulating forces of the adductors.

-

-

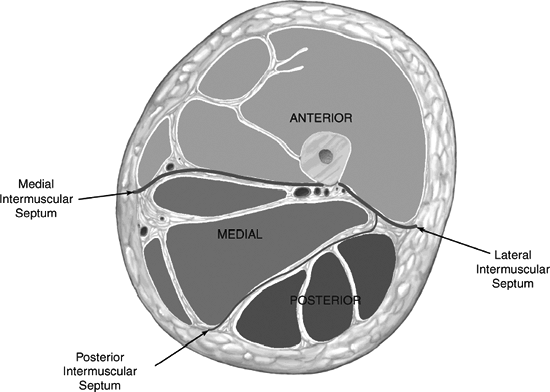

The thigh musculature is divided into three distinct fascial compartments (Fig. 32.2):

-

Anterior compartment: This is composed of

the quadriceps femoris, iliopsoas, sartorius, and pectineus, as well as

the femoral artery, vein, and nerve, and the lateral femoral cutaneous

nerve. Figure 32.1. Deforming muscle forces on the femur; abductors (A), iliopsoas (B), adductors (C), and gastrocnemius origin (D). The medial angulating forces are resisted by the fascia lata (E).

Figure 32.1. Deforming muscle forces on the femur; abductors (A), iliopsoas (B), adductors (C), and gastrocnemius origin (D). The medial angulating forces are resisted by the fascia lata (E).

Potential sites of vascular injury after fracture are at the adductor

hiatus and the perforating vessels of the profunda femoris.(From Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults, 5th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.)![]() Figure 32.2. Cross-sectional diagram of the thigh demonstrates the three major compartments.(From Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown C, et al., eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.)

Figure 32.2. Cross-sectional diagram of the thigh demonstrates the three major compartments.(From Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown C, et al., eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.) -

Medial compartment: This contains the

gracilis, adductor longus, brevis, magnus, and obturator externus

muscles along with the obturator artery, vein, and nerve, and the

profunda femoris artery. -

Posterior compartment: This includes the

biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus, a portion of the

adductor magnus muscle, branches of the profunda femoris artery, the

sciatic nerve, and the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve. -

Because of the large volume of the three

fascial compartments of the thigh, compartment syndromes are much less

common than in the lower leg. -

The vascular supply to the femoral shaft

is derived mainly from the profunda femoral artery. The one to two

nutrient vessels usually enter the bone proximally and posteriorly

along the linea aspera. This artery then arborizes proximally and

distally to provide the endosteal circulation to the shaft. The

periosteal vessels also enter the bone along the linea aspera and

supply blood to the outer one-third of the cortex. The endosteal

vessels supply the inner two-thirds of the cortex. -

Following most femoral shaft fractures,

the endosteal blood supply is disrupted, and the periosteal vessels

proliferate to act as the primary source of blood for healing. The

medullary supply is eventually restored late in the healing process. -

Reaming may further obliterate the endosteal circulation, but it returns fairly rapidly, in 3 to 4 weeks.

-

Femoral shaft fractures heal readily if

the blood supply is not excessively compromised. Therefore, it is

important to avoid excessive periosteal stripping, especially

posteriorly, where the arteries enter the bone at the linea aspera.

P.347P.348 -

MECHANISM OF INJURY

-

Femoral shaft fractures in adults are

almost always the result of high-energy trauma. These fractures result

from motor vehicle accident, gunshot injury, or fall from a height. -

Pathologic fractures, especially in the

elderly, commonly occur at the relatively weak metaphyseal-diaphyseal

junction. Any fracture that is inconsistent with the degree of trauma

should arouse suspicion for pathologic fracture. -

Stress fractures occur mainly in military

recruits or runners. Most patients report a recent increase in training

intensity just before the onset of thigh pain.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

-

Because these fractures tend to be the result of high-energy trauma, a full trauma survey is indicated.

-

The diagnosis of femoral shaft fracture

is usually obvious, with the patient presenting nonambulatory with

pain, variable gross deformity, swelling, and shortening of the

affected extremity. -

A careful neurovascular examination is

essential, although neurovascular injury is uncommonly associated with

femoral shaft fractures. -

Thorough examination of the ipsilateral

hip and knee should be performed, including systematic inspection and

palpation. Range-of-motion or ligamentous testing is often not feasible

in the setting of a femoral shaft fracture and may result in

displacement. Knee ligament injuries are common, however, and need to

be assessed after fracture fixation. -

Major blood loss into the thigh may

occur. The average blood loss in one series was greater than 1200 mL,

and 40% of patients ultimately required transfusions. Therefore, a

careful preoperative assessment of hemodynamic stability is essential,

regardless of the presence or absence of associated injuries.

P.349

ASSOCIATED INJURIES

-

Associated injuries are common and may be

present in up to 5% to 15% of cases, with patients presenting with

multisystem trauma, spine, pelvis, and ipsilateral lower extremity

injuries. -

Ligamentous and meniscal injuries of the ipsilateral knee are present in 50% of patients with closed femoral shaft fractures.

RADIOGRAPHIC EVALUATION

-

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views of the femur, hip, and knee as well as an AP view of the pelvis should be obtained.

-

The radiographs should be critically

evaluated to determine the fracture pattern, the bone quality, the

presence of bone loss, associated comminution, the presence of air in

the soft tissues, and the amount of fracture shortening. -

One must evaluate the region of the proximal femur for evidence of an associated femoral neck or intertrochanteric fracture.

-

If a computed tomography scan of the

abdomen and/or pelvis is obtained for other reasons, this should be

reviewed because it may provide evidence of injury to the ipsilateral

acetabulum or femoral neck.

CLASSIFICATION

Descriptive

-

Open versus closed injury

-

Location: proximal, middle, or distal one-third

-

Location: isthmal, infraisthmal or supracondylar

-

Pattern: spiral, oblique, or transverse

-

Comminuted, segmental, or butterfly fragment

-

Angulation or rotational deformity

-

Displacement: shortening or translation

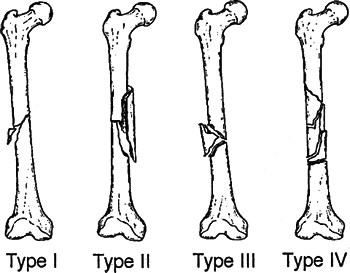

Winquist and Hansen (Fig. 32.3)

-

This is based on fracture comminution.

-

It was used before routine placement of statically locked IM nails.

| Type I: | Minimal or no comminution |

| Type II: | Cortices of both fragments at least 50% intact |

| Type III: | 50% to 100% cortical comminution |

| Type VI: | Circumferential comminution with no cortical contact |

OTA Classification of Femoral Shaft Fractures

See Fracture and Dislocation Compendium at http://www.ota.org/compendium/index.htm.

TREATMENT

Nonoperative

Skeletal Traction

-

Currently, closed management as

definitive treatment for femoral shaft fractures is largely limited to

adult patients with such significant medical comorbidities that

operative management is contraindicated. -

The goal of skeletal traction is to

restore femoral length, limit rotational and angular deformities,

reduce painful spasms, and minimize blood loss into the thigh. Figure 32.3. Winquist and Hansen classification of femoral shaft fractures.(From Browner BD, Jupiter JB, Levine AM, et al. Skeletal Trauma. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1992:1537.)

Figure 32.3. Winquist and Hansen classification of femoral shaft fractures.(From Browner BD, Jupiter JB, Levine AM, et al. Skeletal Trauma. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1992:1537.) -

Skeletal traction is usually used as a

temporizing measure before surgery to stabilize the fracture and

prevent fracture shortening. -

Twenty to 40 lb of traction is usually applied and a lateral radiograph checked to assess fracture length.

-

Distal femoral pins should be placed in

an extracapsular location to avoid the possibility of septic arthritis.

Proximal tibia pins are typically positioned at the level of the tibial

tubercle and are placed in a bicortical location. -

Safe pin placement is usually from medial

to lateral at the distal femur (directed away from the femoral artery)

and from lateral to medial at the proximal tibia (directed away from

the peroneal nerve). -

Problems with use of skeletal traction

for definitive fracture treatment include knee stiffness, limb

shortening, prolonged hospitalization, respiratory and skin ailments,

and malunion.

P.350

Operative

-

Operative stabilization is the standard of care for most femoral shaft fractures.

-

Surgical stabilization should occur within 24 hours, if possible.

-

Early stabilization of long bone injuries appears to be particularly important in the multiply injured patient.

Intramedullary (IM) Nailing

-

This is the standard of care for femoral shaft fractures.

-

Its IM location results in lower tensile

and shear stresses on the implant than plate fixation. Benefits of IM

nailing over plate fixation include less extensive exposure and

dissection, lower infection rate, and less quadriceps scarring. -

Closed IM nailing in closed fractures has

the advantage of maintaining both the fracture hematoma and the

attached periosteum. If reaming is performed, these elements provide a

combination of osteoinductive and osteoconductive materials to the site

of the fracture. -

Other advantages include early functional

use of the extremity, restoration of length and alignment with

comminuted fractures, rapid and high union (>95%), and low

refracture rates.

P.351

Antegrade Inserted Intramedullary (IM) Nailing

-

Surgery can be performed on a fracture table or on a radiolucent table with or without skeletal traction.

-

The patient can be positioned supine or

lateral. Supine positioning allows unencumbered access to the entire

patient. Lateral positioning facilitates identification of the

piriformis starting point but may be contraindicated in the presence of

pulmonary compromise. -

One can use either a piriformis fossa or

greater trochanteric starting point. The advantage of a piriformis

starting point is that it is in line with the medullary canal of the

femur. However, it is easier to locate the greater trochanteric

starting point. Use of a greater trochanteric starting point requires

use of a nail with a valgus proximal bow to negotiate the off starting

point axis. -

With the currently available nails, the

placement of large diameter nails with an intimate fit along a long

length of the medullary canal is no longer necessary. -

The role of unreamed IM nailing for the

treatment of femoral shaft fractures remains unclear. The potentially

negative effects of reaming for insertion of IM nails include elevated

IM pressures, elevated pulmonary artery pressures, increased fat

embolism, and increased pulmonary dysfunction. The potential advantages

of reaming rate include the ability to place a larger implant,

increased union, and decreased hardware failure. -

All IM nails should be statically locked

to maintain femoral length and control rotation. The number of distal

interlocking screws necessary to maintain the proper length, alignment,

and rotation of the implant bone construct depends on numerous factors

including fracture comminution, fracture location, implant size,

patient size, bone quality, and patient activity.

Retrograde Inserted Intramedullary (IM) Nailing

-

The major advantage with a retrograde entry portal is the ease in properly identifying the starting point.

-

Relative indications include:

-

Ipsilateral injuries such as femoral neck, pertrochanteric, acetabular, patellar, or tibial shaft fractures.

-

Bilateral femoral shaft fractures.

-

Morbidly obese patient.

-

Pregnant woman.

-

Periprosthetic fracture above a total knee arthroplasty.

-

Ipsilateral through knee amputation in a patient with an associated femoral shaft fracture.

-

-

Contraindications include:

-

Restricted knee motion <60 degrees.

-

Patella baja.

-

The presence of an associated open traumatic wound, secondary to the risk of intraarticular knee sepsis.

-

P.352

External Fixation

-

Use as definitive treatment for femoral shaft fractures has limited indications.

-

Its use is most often provisional.

-

Advantages include the following:

-

The procedure is rapid; A temporary external fixator can be applied in less than 30 minutes.

-

The vascular supply to the femur is minimally damaged during application.

-

No additional foreign material is introduced in the region of the fracture.

-

It allows access to the medullary canal and the surrounding tissues in open fractures with significant contamination.

-

-

Disadvantages: Most are related to use of this technique as a definitive treatment and include:

-

Pin tract infection.

-

Loss of knee motion.

-

Angular malunion and femoral shortening.

-

Limited ability to adequately stabilize the femoral shaft.

-

Potential infection risk associated with conversion to an IM nail.

-

-

Indications for use of external fixation include:

-

Use as a temporary bridge to IM nailing in the severely injured patient.

-

Ipsilateral arterial injury that requires repair.

-

Patients with severe soft tissue contamination in whom a second debridement would be limited by other devices.

-

Plate Fixation

Plate fixation for femoral shaft stabilization has decreased with the use of IM nails.

-

Advantages to plating include:

-

Ability to obtain an anatomic reduction in appropriate fracture patterns.

-

Lack of additional trauma to remote locations such as the femoral neck, the acetabulum, and the distal femur.

-

-

Disadvantages compared with IM nailing include:

-

Need for an extensive surgical approach

with its associated blood loss, risk of infection, and soft tissue

insult. This can result in quadriceps scarring and its effects on knee

motion and quadriceps strength. -

Decreased vascularization beneath the plate and the stress shielding of the bone spanned by the plate.

-

The plate is a load bearing implant; therefore, higher rate of implant failure.

-

-

Indications include:

-

Extremely narrow medullary canal where IM nailing is impossible or difficult.

-

Fractures that occur adjacent to or through a previous malunion.

-

Obliteration of the medullary canal due to infection or previous closed management.

-

Fractures that have associated proximal or distal extension into the pertrochanteric or condylar regions.

-

In patients with an associated vascular

injury, the exposure for the vascular repair frequently involves a wide

exposure of the medial femur. If rapid femoral stabilization is

desired, a plate can be applied quickly through the medial open

exposure.

P.353 -

-

An open or a submuscular technique may be applicable.

-

As the fracture comminution increases, so

should the plate length such that at least four to five screw holes of

plate length are present on each side of the fracture. -

The routine use of cancellous bone

grafting in plated femoral shaft fractures is questionable if indirect

reduction techniques are used.

Femur Fracture in Multiply Injured Patient

-

The impact of femoral nailing and reaming is controversial in the polytrauma patient.

-

In a specific subpopulation of patients

with multiple injuries, early IM nailing is associated with elevation

of certain proinflammatory markers. -

It has been recommended that early

external fixation of long bone fractures followed by delayed IM nailing

may minimize the additional surgical impact in patients at high risk

for developing complications (i.e., patients in extremis or

underresuscitated).

Ipsilateral Fractures of the Proximal or Distal Femur

-

Concomitant femoral neck fractures occur

in 3% to 10% of patients with femoral shaft fractures. Options for

operative fixation include antegrade IM nailing with multiple screw

fixation of the femoral neck, retrograde femoral nailing with multiple

screw fixation of the femoral neck, and compression plating with screw

fixation of the femoral neck. The sequence of surgical stabilization is

controversial. -

Ipsilateral fractures of the distal femur

may exist as a distal extension of the shaft fracture or as a distinct

fracture. Options for fixation include fixation of both fractures with

a single plate, fixation of the shaft and distal femoral fractures with

separate plates, IM nailing of the shaft fracture with plate fixation

of the distal femoral fracture, or interlocked IM nailing spanning both

fractures (high supracondylar fractures).

Open Femoral Shaft Fractures

-

These are typically the result of high-energy trauma.

-

Patients frequently have multiple other orthopaedic injuries and involvement of several organ systems.

-

Treatment is emergency debridement with skeletal stabilization.

-

Stabilization can usually involve placement of a reamed IM nail.

P.354

REHABILITATION

-

Early patient mobilization out of bed is recommended.

-

Early range of knee motion is indicated.

-

Weight bearing on the extremity is guided

by a number of factors including the patient’s associated injuries,

soft tissue status, and the location of the fracture.

COMPLICATIONS

-

Nerve injury: This is uncommon because

the femoral and sciatic nerves are encased in muscle throughout the

length of the thigh. Most injuries occur as a result of traction or

compression during surgery. -

Vascular injury: This may result from tethering of the femoral artery at the adductor hiatus.

-

Compartment syndrome: This occurs only

with significant bleeding. It presents as pain out of proportion, tense

thigh swelling, numbness or paresthesias to medial thigh (saphenous

nerve distribution), or painful passive quadriceps stretch. -

Infection (<1% incidence in closed

fractures): The risk is greater with open versus closed IM nailing.

Grades I, II, and IIIA open fractures carry a low risk of infection

with IM nailing, whereas fractures with gross contamination, exposed

bone, and extensive soft tissue injury (grades IIIB, IIIC) have a

higher risk of infection regardless of treatment method. -

Refracture: Patients are vulnerable

during early callus formation and after hardware removal. It is usually

associated with plate or external fixation. -

Nonunion and delayed union: This is

unusual. Delayed union is defined as healing taking longer than 6

months, usually related to insufficient blood supply (i.e., excessive

periosteal stripping), uncontrolled repetitive stresses, infection, and

heavy smoking. Nonunion is diagnosed once the fracture has no further

potential to unite. -

Malunion: This is usually varus, internal rotation, and/or shortening owing to muscular deforming forces or surgical technique.

-

Fixation device failure: This results from nonunion or “cycling” of device, especially with plate fixation.

-

Heterotopic ossification may occur.