Examination of Upper Extremity Muscle Strength

– Neurologic Examination > Motor Examination > Chapter 25 –

Examination of Upper Extremity Muscle Strength

strength is to localize neurologic pathology by looking for

characteristic distributions of muscle weakness.

Performing a Complete Neurologic Examination) should be performed on

all patients as part of the routine neurologic examination. If weakness

is suspected or found, a more detailed evaluation of upper (and lower)

extremity muscles is indicated to try to localize the patient’s

pathology.

of the upper extremities end primarily within the cervical spinal cord,

proceeding no further caudally than the first thoracic level. The lower

motor neurons that innervate the muscles of the arms leave the spinal

cord primarily from the C5 through the T1 levels. Table 25-1

summarizes the major innervation (root and nerve) of some of the most

clinically relevant muscles of the upper extremities, as well as the

functions of these muscles.

-

Ask the patient to hold his or her arms straight in front of him or her with the palms up.

-

Instruct the patient to close his or her eyes.

-

Observe the arms for a few seconds while the patient’s eyes are closed.

|

TABLE 25-1 Major Innervation of the Muscles of the Upper Extremities

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(drift) of the outstretched arms when the eyes are closed, and there

should be no atrophy or fasciculations of the muscles. Strength should

be full (5/5) and symmetric in all muscles tested of the arms.

|

|

Figure 25-1

Examination of arm abduction (deltoid) strength. Ask the patient to hold his or her arm up 90 degrees at the shoulder (“like a chicken”) and then ask the patient to resist you as you push down on his or her abducted arm. What you might say as you test the strength: “Don’t let me push your arm down.” |

|

|

Figure 25-2

Examination of elbow flexion (biceps) strength. Ask the patient to flex his or her arm at approximately 90 degrees at the elbow, with his or her palm facing the shoulder (“like you are making a muscle”), and then ask the patient to resist you as you attempt to extend his or her arm. What you might say as you test the strength: “Don’t let me pull on your arm.” |

|

|

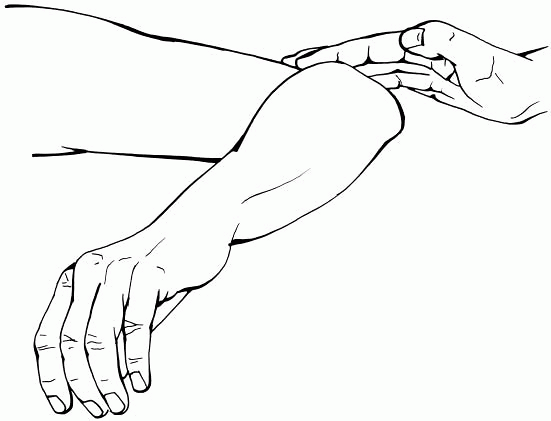

Figure 25-3

Examination of elbow flexion (brachioradialis) strength. Ask the patient to flex his or her arm at approximately 90 degrees at the elbow, with the patient’s forearm partially pronated so that the radial wrist is facing his or her shoulder, and then ask the patient to resist you as you attempt to extend the arm. What you might say as you test the strength: “Don’t let me pull on your arm.” |

|

|

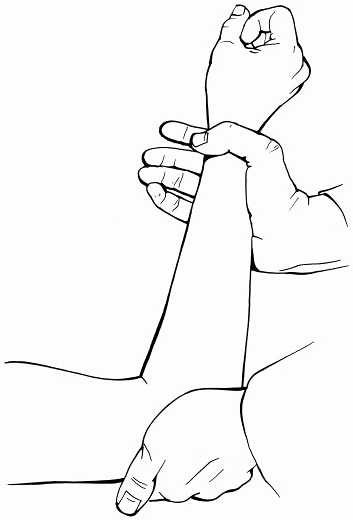

Figure 25-4

Examination of elbow extension (triceps) strength. Ask the patient to start with his or her arm bent at approximately 90 degrees at the elbow, and then as you push on his or her arm, ask the patient to try to push the arm out (by extending at the elbow) against your resistance. What you might say as you test the strength: “Try to push your arm out.” |

|

|

Figure 25-5

Examination of wrist extension (extensor carpi radialis and extensor carpi ulnaris) strength. Ask the patient to lift (extend) his or her hand at the wrist, and then ask the patient to resist you as you attempt to push down on his or her extended hand. What you might say as you test the strength: “Don’t let me push your hand down.” |

|

|

Figure 25-6

Examination of finger extension (extensor digitorum communis) strength. Ask the patient to lift (extend) his or her fingers, and then ask the patient to resist you as you attempt to push down on the extended fingers. What you might say as you test the strength: “Don’t let me push your fingers down.” |

|

|

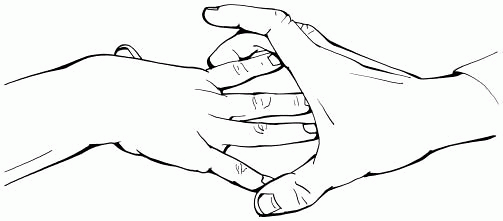

Figure 25-7

Examination of finger abduction (dorsal interossei) strength. Ask the patient to spread his or her fingers apart, and then ask the patient to resist you as you use your thumb and middle finger to attempt to close his or her fingers. What you might say as you test the strength: “Don’t let me squeeze your fingers together.” |

|

|

Figure 25-8

Examination of thumb abduction (abductor pollicis brevis) strength. Ask the patient to lift his or her thumb up (perpendicular to the plane of the palm), and then ask the patient to resist as you attempt to push the thumb down. What you might say as you test the strength: “Don’t let me push your thumb down.” |

|

|

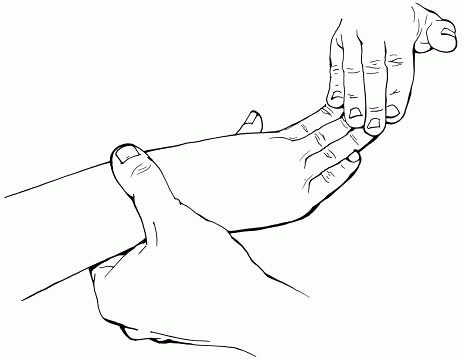

Figure 25-9

Examination of thumb flexion (flexor pollicis longus) strength. Ask the patient to flex the distal joint of the thumb, and then ask the patient to resist you as you attempt to straighten the thumb. (Similar testing can be done to test the flexor digitorum profundus that flexes the distal phalanx of the fingers.) What you might say as you test the strength: “Don’t let me pull your thumb.” |

-

The finding of any downward drift of an

arm when the patient’s eyes are closed suggests weakness of that

extremity due to any cause. -

Downward drift of an arm can occur with or without pronation. When it occurs with pronation, the term pronator drift is often used. Whether the downward drift occurs with or without pronation, the significance—weakness—is the same.

-

Rarely, when drift is tested, an arm may

assume unusual posturing at multiple joints, sometimes with significant

upward movement. This finding suggests the possibility of a

proprioceptive problem (see Chapter 30,

Examination of Vibration and Position Sensation), as can be seen from

disorders of the spinal cord, sensory nerves or roots, or contralateral

parietal lobe.

-

Any muscle strength in the arms that is less than 5/5 is abnormal.

-

Any focal muscle atrophy or

fasciculations in the muscles of the arms is abnormal and suggests

dysfunction of the lower motor neuron supplying those muscles. -

Look for patterns of muscle weakness (in

the arms as well as the legs) to support or refute your suspicion of

the localization of the cause of weakness to the brain, spinal cord,

root, plexus, or nerve (see Table 24-3).

-

The test for drift is an important part

of the motor examination because even subtle downward drift of an arm

suggests weakness in that extremity,

P.81

even

before you perform any individual muscle strength testing. Think of

drift as the sneak preview to the motor examination. Finding drift

suggests there is subtle extremity weakness regardless of whether

further evidence for weakness is seen on muscle testing. -

The muscles described in this chapter are

not inclusive of all the muscles of the arms that may need to

occasionally be tested to localize a cause of weakness, but they do

represent muscles that are particularly helpful to have a working

knowledge of for the majority of neurologic examinations.