Cast and Bandaging Techniques

-

Plaster (1,2)

-

Plaster bandages and splints are made by impregnating crinoline with plaster of paris [CaSO4)2H2O].

When this material is dipped into water, the powdery plaster of paris

is transformed into a solid crystalline form of gypsum, and heat is

given off:

-

The amount of heat given off is determined by the amount of plaster applied and the temperature of the water (3,4).

The more plaster and the hotter the water, the more heat is generated.

The interlocking of the crystals formed is essential to the strength

and rigidity of the cast. Motion during the critical setting period

interferes with this interlocking process and reduces the ultimate

strength by as much as 77%. The interlocking of crystals (the critical

setting period) begins when the plaster reaches the thick creamy stage,

becomes a little rubbery, and starts losing its wet, shiny appearance.

Cast drying occurs by the evaporation of the water not required for

crystallization. The evaporation from the cast surface is influenced by

air temperature, humidity, and circulation about the cast. Thick casts

take longer to dry than thin ones. Strength increases as drying occurs. -

Plaster is available as bandage rolls in widths of 8, 6, 3, and 2 inches and splints

in 5- × 45-inch, 5- × 30-inch, and 3- × 15-inch sizes. Additives are

used to alter the setting time. Three variations are available.

Extra-fast setting takes 2 to 4 minutes, fast setting takes 5 to 6

minutes, and slow setting takes 10 to 18 minutes.

-

-

Fiberglass cast.

In recent years, a number of companies have developed materials to

replace plaster of paris as a cast. Most of these are a fiberglass

fabric impregnated with polyurethane resin. The prepolymer is methylene

bisphenyl diisolynate, which converts to a nontoxic polymeric urea

substitute. The exothermic reaction does not place the patient’s skin

at risk for thermal injury (2,5,6).

These materials are preferred for most orthopaedic applications except

in acute fractures in which reduction maintenance is critical.

Fiberglass casts do not provide higher skin pressure when compared to

plaster casts when properly applied (7).-

Advantages.

These materials are strong, lightweight, and resist breakdown in water;

they are also available in multiple colors and patterns. -

Disadvantages.

They are harder to contour than plaster of paris, and the polyurethane

may irritate the skin. Fiberglass is harder to apply, although the

newer bias stretch material is an improvement. Review in detail the

instructions from each manufacturer before using the casting materials.

Patients are commonly under the impression that fiberglass casts can be

gotten wet. This is incorrect; if submerged, they need to be changed to

avoid significant skin maceration.

-

-

The water.

Warm water causes more heat to be given off and affords faster setting.

Cold water allows for less heat and for slower setting. Plaster of

paris in the water

P.102

bucket

from previously dipped plaster accelerates the setting time. The water

used for dipping should be deep enough to cover the material rolls

standing on end. -

Cast padding

-

Webril has a

smooth surface and less tendency for motion within the thickness of the

padding than some of the other padding materials. It requires the most

practice to achieve a smooth application, however. -

Specialist is

softer than Webril and contains wood fiber. It has a corrugated

appearance, and there is more tendency for sliding to occur within the

material. It is easier to apply without wrinkles than Webril, but it

becomes very hard if caked with blood. -

Sof-Roll is a

soft padding similar in appearance to Webril but slightly thicker. It

has greater tear resistance and is therefore easier to stretch. -

Stockinet

-

Bias-cut

stockinet may be used under a cast as a single layer. It is easy to

apply without wrinkles and is better than tubular stockinet if there is

a large difference in the maximum and minimum diameters of the

extremity. Bias-cut stockinet can be made snug throughout, in contrast

to tubular stockinet, which can be snug in the large diameter of the

extremity but very loose in the narrow diameter. Plaster sticks to the

stockinet, so there is no sliding between the cast and the stockinet

padding. -

Tubular stockinet is made of the same material as the bias-cut type and is available in varying tube sizes from 2 to 12 inches.

-

-

Felt or Reston

should be used to pad bony prominences and for cast margins. When

padding over bony prominences, such as the anterior superior iliac

spine, make a cruciate incision in the felt for better contouring. -

Moleskin adhesive can be used to trim cast margins.

-

-

Adherent materials.

Adherent substances (such as Dow Corning medical adhesive B) are

applied to prevent slipping and chafing between the skin and the

padding. They can contribute, however, to an increased amount of

itching inside the cast. Tincture of benzoin compound should not be

used in this situation because of fairly frequent skin reactions.

Commercial adhesive removers are available. -

Equipment

-

Use a clean bucket. Plaster residue and other particles in the water can alter the setting time.

-

Gloves keep

hands clean and prevent dry skin if one applies many casts. They also

make a smoother finish than is achieved by bare hands. They are

mandatory for working with fiberglass materials. -

Shoe covers and aprons or gowns keep shoes and clothes clean to prevent one from appearing sloppy in plaster-covered attire.

-

Use appropriate draping to maintain the dignity of the patient as well as to keep plaster off all areas not casted.

-

Cast cutters

-

The cast-cutting electric saw

has an oscillating circular blade that cuts firm rigid surfaces, such

as casts or bony prominences. When lightly touched, the skin vibrates

with the blade but the blade does not cut. If the blade is firmly

pressed against the skin or dragged along it, then it will cut. The saw

is noisy and causes considerable anxiety, especially in children.

Therefore, it is wise to show younger patients that cast saws are safe

by touching the blade to the palm of the hand. The cast saw causes dust

to fly; consequently, use of this tool is best avoided in clean

operating rooms. In addition, cast saws can cut skin if applied with

excessive force, so it is unwise to use them on anesthetized patients. -

Hand cutters

are useful when a saw is not available or to avoid frightening a child

with the noise of the saw, to lessen the amount of plaster dust in the

operating room, and to remove damp plaster.

-

-

Cast spreaders

are used to open the cut edges of a cast for access to underlying cast

padding, which is then cut with scissors. Spreaders come in various

sizes for large and small casts. -

Cast knives

have sharp blades, and preferably have large handles for better

control. Sharp blades are essential; therefore, most practitioners

prefer to use no. 22 disposable surgical blades. -

Cast benders adjust cast edges to relieve skin binding and pressure.

-

Cast dryers

blow warm to hot air around a plaster cast. They are generally not

necessary. An exposed cast and a fan work just as well and are safer.

Cast dryers can burn skin and tend to hasten the drying time of the

outer layers only.

P.103 -

-

Casts are used for the following purposes:

-

To immobilize

fractures, dislocations, injured ligaments, and joints; to provide

relief from pain caused by infections and inflammatory processes; and

to facilitate healing -

To allow earlier ambulation by stabilizing fractures of the spine or lower extremities

-

To improve function

by stabilizing or positioning a joint, such as for wrist drop after a

radial nerve injury, which also allows more useful hand function -

To correct deformities, as in serial casting for clubfoot or joint contractures

-

To prevent deformity resulting from a neuromuscular imbalance or from scoliosis

-

-

Principles.

Although plaster of paris has been used extensively in the treatment of

fractures for more than 100 years, there is no unanimity of opinion as

to the best technique for application. It can be safely concluded that

even the tightest of skintight casts allows some motion at the fracture

site, whereas a loosely fitted, well-padded cast with proper

three-point fixation can provide satisfactory immobilization. Three

points of force are produced by the practitioner, who molds the cast

firmly against the proximal and distal portions of the extremity (two

of the points) and locates the third point directly opposite the apex

of the cast, as shown in Fig. 7-1.

Periosteal or other soft-tissue attachments usually are required on the

convex side of the cast to provide stability. In this way, a curved

cast can provide straight alignment of the extremity within it.

Charnley has stated, “If a fracture slips in a well-applied plaster,

then the fracture was mechanically unsuitable for treatment by plaster,

and another mechanical principle should have been chosen.” Another

method for providing immobilization by plaster is based on hydraulics.

Fractures of the tibia do not shorten significantly when placed in a

“total contact” cast. The leg is a cylinder containing mostly fluid,

and when this water column is encased in rigid plaster, the cylinder

does not shorten in height because tissue fluid is not compressible. -

The following application techniques have been satisfactory in our hands:

-

The patient is informed of the procedure and instructed in whatever cooperation is necessary.

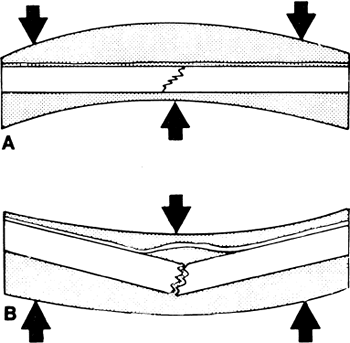

![]() Figure 7-1. A:

Figure 7-1. A:

Three-point plaster fixation will stabilize a fracture when the soft

tissue bridging the fracture acts as a hinge under tension. B: If the three forces are applied in the wrong direction, the fracture displaces. -

The surgeon or cast technician must have clearly in mind what to do and what will be required

(the position of the patient and assistants, how many rolls of plaster

will be needed, tools to trim the cast edges, etc.). All material and

equipment required to do the job properly should be assembled. (Once

cast application starts, it is difficult to stop and obtain something

that was forgotten.) The patient’s position must be comfortable and

must allow the surgeon and assistant to apply the cast expeditiously.

Special maneuvers required to perform and hold the reduction are

rehearsed. -

A circular cast should not be used in fresh trauma or postoperatively when one anticipates swelling, unless the cast is bivalved or split initially and provisions are made for adequate observation.

-

Adequate observation

means an examination by a competent observer at least once hourly until

any swelling begins to recede. Signs of compartmental syndrome, in

order of importance, are the following: increasing pain and discomfort

in the extremity, increasing tenseness or tenderness in the involved

compartment, pain with passive range of motion of the muscle in the

involved compartment, decreasing sensation—especially to two-point

discrimination and light touch—in the distribution of the nerves that

travel through the involved compartment, increasing peripheral edema,

and, finally, decreasing capillary filling. Good peripheral circulation with distal arterial pulses is no assurance that a compartmental syndrome is not developing (see Chap. 2, III). -

An excellent alternative to plaster casts in this situation is a Jones compression splint, as described in Chap. 6, III.B and C.

-

-

If unexpected swelling occurs in a circular cast, bivalve or split the cast immediately all the way to the patient’s skin as described in IV.B and C.

-

Unless specifically contraindicated, clean

the part to be casted with soap and water, then dry it with alcohol.

Apply the cast over a single layer of cast padding with edges of the

material minimally overlapping. Protect unusual bony prominences with a

1/4-inch felt or foam rubber padding. -

Dip the plaster or fiberglass rolls in water

by placing them on end, which allows air to escape and results in

complete soaking of the plaster. The bandages are sufficiently soaked

when the bubbling stops. They can be left in the water up to 4 minutes

without decreasing the strength of the cast, but the setting time

decreases the longer they are immersed. Therefore, for maximum working

time, remove bandages soon after the bubbling stops. Lightly crimping

the ends of the plaster bandages helps prevent telescoping of the roll. -

Except for very large casts (e.g., body casts, spicas), all plaster bandages should be dipped and removed from the water at the same time.

Thus, all the plaster in the cast is at the same point in the setting

process. This scheme maximizes the interlocking of the crystals between

the layers of plaster, thereby maximizing the strength of the cast. In

addition, delamination between the bandages is decreased. -

Use cool water for larger casts when more time is needed to apply all the plaster or fiberglass, and use warm water for smaller casts or splints. Never use hot water because enough heat can be generated to burn the patient (8).

Similarly, do not place limbs with fresh casts onto plastic-covered

pillows; these tend to hamper heat dispersion significantly and may

result in burning. If the patient complains of burning, it is prudent

to remove the cast immediately and reapply using cooler water. -

Keep the plaster bandage on the cast

padding, lifting it off only to tuck and change directions—that is, to

push the plaster roll around the patient’s body or extremity. Use the

largest bandages, usually 4- and 6-in. bandage rolls, that are

consistent with smooth, easy applications. Using large bandages allows

the fastest application of plaster and provides sufficient time for

molding before the critical setting period. Six or seven layers of plaster

or two to three layers of fiberglass usually are sufficient, except in

individuals who are particularly hard on casts. The cast should be of

uniform thickness (seven layers or

P.105

1/4

in.). Avoid concentrating the plaster about the fracture or the middle

of the cast. Avoid placing two circumferential rolls directly on top of

each other while wrapping the plaster on the patient’s extremity.

Reinforce casts where they cross joints by incorporating plaster or

fiberglass splints longitudinally. Incorporate reinforcing plaster

splints into body and spica casts as described later in this chapter (III.B and C). -

During application of the cast, turn the padding back at the edges of the cast and incorporate it.

Another method of finishing the edges is to turn back the padding after

the cast has set and to hold the padding down with a single, narrow,

plaster splint; a row of ordinary staples; or moleskin. -

Apply all the material rapidly

so there is time to work and mold it before the critical setting

period. The cast should have a sculptured look, not only for cosmetic

reasons but also for comfort. If the fracture is to be stabilized by

the three-point fixation principle, it is more important to maintain

the three forces of pressure on the cast during the critical setting

period than to have a perfectly smooth surface on the cast. This step

is more difficult for fiberglass casts. -

Once the critical period of interlocking of crystals begins, molding and all motion should stop until the material becomes rigid. Otherwise, the cast is weakened considerably.

-

After the cast sets and becomes rigid, trim the edges

using a plaster knife or cast saw. Use the knife by supporting the

cutting hand on the cast and pulling the portion of the plaster to be

trimmed up against the knife blade rather than blindly cutting through

the plaster and possibly cutting the patient. If the cast is too thick

or hard, an oscillating cast saw is preferred. -

Apply forearm casts to allow full 90 degrees flexion of all metacarpophalangeal joints and opposition of the thumb to the index and little fingers.

-

Extend leg casts

to support the metatarsal heads but not to interfere with flexion and

extension of the toes. This rule is invalid when the toes need support

(as with fractures of the great toe or metatarsals) or when there is a

motor or sensory deficit. In these situations, the cast is extended as

a platform to support and protect the toes. Place a 1/2-inch piece of

sponge rubber beneath the toes and incorporate it into the plaster for

walking casts, or supply the patient with a commercial cast shoe. -

Immobilize as few joints as possible, but as a general rule, one immobilizes the joint above and below a fresh fracture.

-

Instruct the patient regarding

-

Signs and symptoms of compression from swelling within the cast

-

Elevation of the injured part above the level of the heart for 2 to 3 days after the injury

-

How soon to walk on the cast (never sooner than 24 hours)

-

Instructions for weight bearing and ambulation; this should include crutch or walker training

-

How to exercise joints not incorporated in plaster

-

Date of the next appointment

-

Person to call in case of cast problems or evidence of a compression syndrome

-

P.104 -

-

Use plaster splints when rigid immobilization is not required or when significant swelling of the extremity is anticipated.

-

Upper extremity

-

Usually splint the wrist

dorsally by applying a 3-in.-wide plaster splint over cast padding from

the metacarpophalangeal joints to the proximal forearm. While the

plaster is still wet, wrap the arm with bias-cut stockinet or a single

layer of an elastic bandage so that the plaster conforms to the

extremity as it hardens. A dorsal splint may be preferable to a volar

splint because it allows easier finger and hand function. Combined

dorsal and volar splints are frequently used together; this is

preferred and gives better support of the limbs. -

Splint the elbow

with 5- × 30-in. plaster wraps applied posteriorly with enough distal

extension to support the wrist. The splint should not go further

distally than the distal palmar crease in order to facilitate

metacarpal-phalangeal motion. Apply 3-in. plaster strips medially and

laterally across the elbow for reinforcement. Wrap the arm and plaster

splint with bias-cut stockinet or a single layer of an elastic bandage

while the plaster is wet.

P.106 -

-

Lower extremity.

Usually make posterior plaster splints in the lower extremity by

applying a standard cast (knee cylinder, short-leg, or long-leg, cast,

as described in III. D, E, F)

and then bivalving the cast and retaining only the posterior shell.

Hold the posterior splint to the leg with bias-cut stockinet or an

elastic bandage wrap. Alternatively, use 5- × 30-in. posterior and

medial/lateral splints, leaving the anterior aspect of the leg covered

only by soft roll.

-

-

Body casts

-

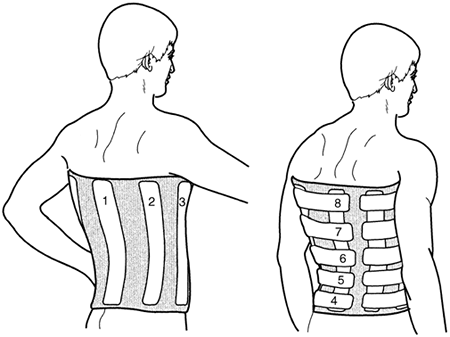

Apply the basic body jacket

over large tubular stockinet. Place 1/8- to 1/2-in. felt pads over the

shoulders (if suspenders are used), costal margins, iliac crests

including anterior iliac spine, and the dorsal spine. Make a cruciate

cut in the felt placed over the crests to distribute pressure uniformly

over the bony prominence. Apply a single layer of plaster snugly over

the padding. Splints may be used, as shown in Fig. 7-2.

If suspenders are required, make a “V” with 5- × 30-in. splints. Place

the point of the “V” between the scapulae and bring the ends over the

shoulders. Snugly apply rolled plaster over the splints and mold.

Usually extend the jacket posteriorly from the top of the sacrum to the

inferior angle of the scapulae and anteriorly from the symphysis pubis

to the sternal notch. Body jackets may be applied with the lumbar spine

in flexion or extension as well as the neutral position. For

hyperextension body jackets, often used in thoracolumbar fractures, use

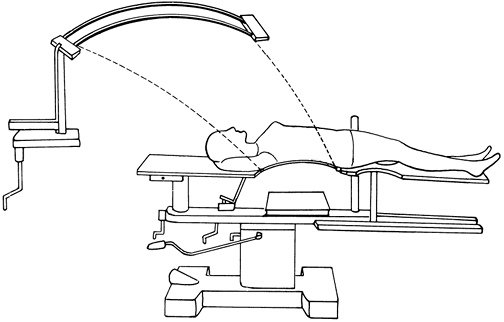

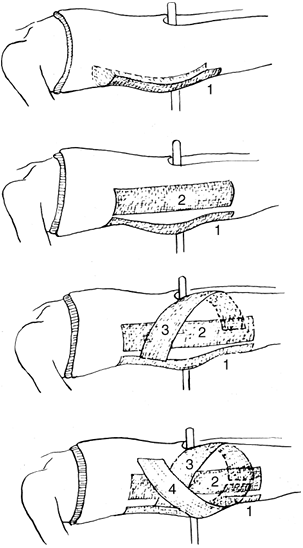

the Goldwaithe iron apparatus for positioning, as in Fig. 7-3. Figure 7-2.

Figure 7-2.

Typical application of plaster splints for a body jacket. The splints

are placed closer together in the lower aspect of the body jacket. The

splints are numbered in order of application.![]() Figure 7-3. Goldwaithe irons, used to make a hyperextension plaster body jacket. The irons are removed after the cast is set.

Figure 7-3. Goldwaithe irons, used to make a hyperextension plaster body jacket. The irons are removed after the cast is set. -

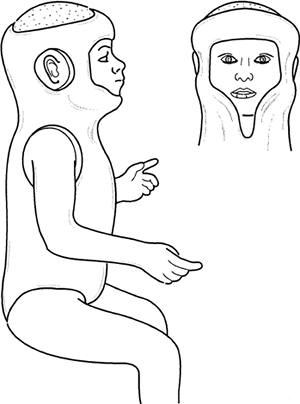

The Minerva body jacket

is named after the goddess Minerva, who sprang forth from Jupiter’s

head when it was cleaved by Vulcan in an attempt to relieve Jupiter’s

headaches. Minerva appeared chanting a triumphant song and wearing a

large metal headdress. The Minerva body jacket incorporates the skull

and is used to immobilize the cervical spine; its most frequent

application is in children. This type of jacket is applied in the same

manner as the body jacket but also calls for the following steps. Place

a fluted felt pad around the entire neck, with the neck halter traction

over the padding. Tie the halter straps at ear level to prevent the

halter’s slipping off the head. Place another felt pad along the length

of the spine and the occiput. Wrap the rest of the head with 3-in.

sheet cotton padding. At least two operators are necessary for even

application of the plaster, one for the head and one for the body. Roll

3-in. plaster bandages about the head and neck. Apply narrow splints

around the chin, neck, occiput, and forehead. Use wide splints all the

way from the sacrum to the occiput, with another wide splint extending

from the chest to the chin. Incorporate these splints into the cast by

snugly wrapping plaster bandages over them. Then mold together the

plaster about the head, neck, and body at the same time. Carefully mold

beneath the mandible. Cut the plaster in a “V” to release the chin and

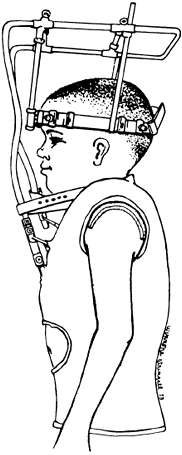

also cut out about the ears and the face (Fig. 7-4,

inset). Trim the plaster above the jaw line and leave the eyebrows

exposed. A Minerva body jacket is useful in children and when cervical

or halo vests (Fig. 7-4) orthoses are not appropriate. -

Other types of body jackets

-

A Risser localizer cast

is occasionally used for scoliotic spines or for patients with

thoracolumbar fractures. Apply a pelvic plaster mold first; then attach

pelvic and head halter traction. Make a pressure pad with felt backed

by four to six layers of plaster. Produce or hold correction of the

scoliosis by applying this pad against the apical ribs and

incorporating it into the body jacket that incorporates the jaw, neck,

and occiput, but not the head. Make the surface of the pressure area

large enough to avoid local necrosis of the skin. Figure 7-4. Completed Minerva body jacket.

Figure 7-4. Completed Minerva body jacket. -

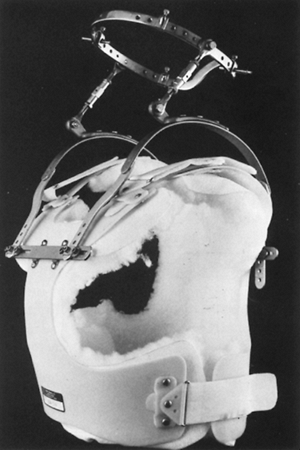

Halo traction

can be incorporated into a plaster or fiberglass body jacket with

suspenders, and it provides continuous or fixed cervical traction (Fig. 7-5).

The halo traction is more commonly incorporated into a sheepskin-lined

plastic body jacket, which is more lightweight and comfortable (Fig. 7-6).

P.108 -

P.107 -

-

Spica

is a Latin word that means “ear of wheat,” because a spica wrap was

used to wrap sheaves of wheat in the fields. The same type of wrap is

used to

P.109

immobilize proximal joints with the spica cast. Various types of spica casts are described here.![]() Figure 7-5. Halo traction cast. (From Bleck EE, Duckworth L, Hunter N. Atlas of plaster cast techniques, 2nd ed. Chicago: Year Book, 1978, with permission.)

Figure 7-5. Halo traction cast. (From Bleck EE, Duckworth L, Hunter N. Atlas of plaster cast techniques, 2nd ed. Chicago: Year Book, 1978, with permission.) Figure 7-6.

Figure 7-6.

A commercially available malleable polyethylene jacket may be

substituted for the plaster cast for use with the halo apparatus.

Patients report this is significantly more comfortable than the plaster

jacket.-

Pad a bilateral short-leg (panty) spica

in much the same way as for the body jacket but include the legs. These

casts are generally applied on fracture tables (adults) or spica boards

(children). Use tubular or bias-cut stockinet. Pad bony prominences

with 1/8- to 1/2-in. felt with cruciate incisions. Apply plaster or

fiberglass to the upper portion of the cast as is done with the body

jacket. Reinforce the hips with splints as shown in Fig. 7-7.

Apply plaster or fiberglass well next to the perineal post under the

sacrum to avoid weakness in the area (the intern’s triangle). Snugly

tie the splints in with plaster or fiberglass bandage rolls extending

to the supracondylar portion of the femurs. Mold the material well over

the iliac crests. The patient may be lifted from the table with the

sacral rest still in the plaster. Turn the patient on his or her

abdomen and cut out the sacral rest. Trim the edges of the cast in the

usual manner. -

Examples of long-leg hip spicas are shown in Fig. 7-8.

Apply the leg portion of the cast like any other long-leg cast, using

the special splints about the hips as described for the short-leg

spica. Support the casted extremities with struts. These are usually

made of wooden stakes (1/4 × 2 in. or 3/4 × 1/2 in.) or

P.110

dowels.

Cover with plaster or fiberglass and attach them to the casted

extremity by wrapping a bandage in a cordlike figure-of-8 fashion about

the strut and cast; then roll the bandage around the strut and cast to

create a well-molded cast. Sedate or anesthetize infants and small

children before spica cast application; they are generally applied in

the operating suite.![]() Figure 7-7. Plaster splints to reinforce hip spicas, in addition to those used in the body jackets.

Figure 7-7. Plaster splints to reinforce hip spicas, in addition to those used in the body jackets. -

Apply the shoulder spica

with the patient standing or supine on a spica table that has a

metallic backrest. The arm may be supported with finger traps, or, with

a cooperative patient in the sitting or standing position, the cast may

be applied while an assistant holds the arm. The principles of padding

and cast application for body jackets and long-arm casts are combined

to produce a shoulder spica. In addition to the splints normally used

for body and long-arm casts, apply a wide splint from the lateral

chest, up under the axilla, to the medial side of the arm. Place other

splints across the posterior aspect of the arm, over the shoulder, to

the opposite side. Tie in the splints with rolled plaster or fiberglass

and place a strut between the arm and trunk.

-

-

Knee cylinder casts.

Remove all hair from the medial and lateral aspects of the lower leg.

Spray the leg with a nonallergenic adhesive. Place medial and lateral

strips of self-adhering foam, moleskin adhesive, or adhesive tape on

the skin with 6 to 12 in. of the material extending distal to the

ankle. Then place a cuff of 1/4-in. sponge rubber or felt padding

measuring 1 in. in width over the strips just above the malleoli. When

the strips are turned back and incorporated into the fiberglass or

P.111P.112

plaster,

they suspend the cast, and with the thick padding, they prevent

pressure on the malleoli. Wrap the leg with a single layer of cast

padding and apply the plaster with the knee flexed 5 degrees. Extend

the cast proximally as far as possible and distally to just above the

flare of the malleoli; the length of the cast provides for lateral and

medial stability. Mold the plaster or fiberglass medially and laterally

above the femoral condyles to help prevent the cast from sliding

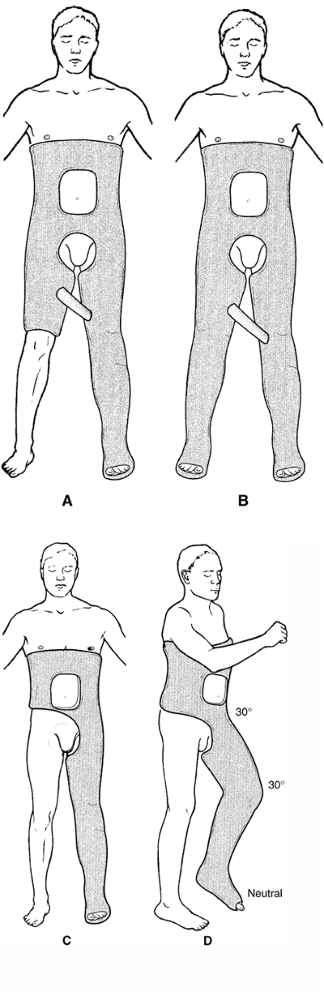

distally. Figure 7-8. Long-leg hip spicas. A: One and one-half spica. B: Double spica. C:

Figure 7-8. Long-leg hip spicas. A: One and one-half spica. B: Double spica. C:

Single spica. For all long-leg spica casts, it is important to keep the

hip and knee gently flexed for patient comfort and ease of positioning.

The ankle must be kept in neutral dorsiflexion (D). In children, it is often advisable to stop the cast at the malleoli distally, leaving the foot free. -

Short-leg casts

-

Apply the short-leg cast

with the patient sitting on the end of a table with the knee flexed 90

degrees. Alternatively, apply it with the patient supine, the hip and

knee flexed 90 degrees, and the leg supported by an assistant. The type

of padding matters little, except that Webril and stockinet tend to

shear less and therefore may allow for a tighter cast over a longer

period of time. Use only one layer of padding except over the malleoli,

where extra padding frequently is required. For most casts, have the

ankle in a neutral position. Two plaster bandages usually are required,

and the width selected (3, 4, or 6 in.) varies with the size of the

patient. Fold 4-in. splints longitudinally in half, and place one

splint on all four sides of the ankle for reinforcement before applying

the second plaster bandage. Extend the cast distally from the

metatarsophalangeal joints and proximally to one finger breadth below

the tibial tubercle. Trim the edges and pad as previously described. -

If desired, a walking cast

may be made with either a rubber rocker walker or a stirrup walker.

Place either one in the midportion of the longitudinal arch of the foot

in line with the anterior border of the tibia. With a rocker walker,

the medial longitudinal arch is filled with plaster splints to make a

flat base. Then the walker is secured with a third plaster bandage.

Commercially available walking shoes (or boots), which fit over the

casted foot, are more widely used. A flat plaster base on the plantar

aspect of the cast is required for these shoes. If the ankle must be

held in equines (such as required for cast treatment of an Achilles

tendon rupture), a stirrup walker is advantageous, and the patient’s

opposite shoe should be adjusted to the appropriate height for walking.

All walking casts should dry for at least 24 hours prior to weight

bearing.

-

-

Long-leg casts

-

First apply a short-leg cast as described earlier (III.E).

Then extend the knee to the position desired and continue the cast

padding to the groin. Two 6-in. plaster or fiberglass bandages usually

are required for the upper portion of this cast except in patients with

heavy thighs. After the first bandage is applied, fold 4- or 5-in.

splints longitudinally and place them medially and laterally across the

knee joint for reinforcement. After the second plaster or fiberglass

bandage is applied, mold the cast medially and laterally in the

supracondylar area to help prevent the cast from slipping distally when

the patient begins to stand. -

The long-leg walking cast is made as described in III.E.2, but the knee must be flexed no more than 5 degrees.

-

-

Casting techniques of Dehne and Sarmiento

-

The cast treatment programs made popular by Dehne and Sarmiento (see Selected Historical Readings)

are designed to allow early weight bearing of a fractured tibia. The

affected leg is placed in a very snug cast that maintains the tissue

and fluids of the leg within a rigid container. Shortening is prevented

by the hydraulic principle that fluids are

not compressible. Thus, the patient can bear weight soon after a

fracture without excessive further shortening, and fracture healing is

benefitted by the improved vascularity derived from ambulation. The

advocates of these casting techniques describe a “total contact cast.”

The authors believe, however, that all casts to the lower extremities

should be total contact casts. -

The long-leg total contact cast as described by Dehne is applied like a long-leg walking cast with only minor modifications.

-

Cast the knee in extension. Some patients, however, find this position uncomfortable and may require a position with 3 to 5 degrees of flexion.

-

This cast may need to be wedged

to correct angular deformities of the fracture site. For this reason,

apply one or two extra layers of the Webril at the fracture site.

P.113 -

-

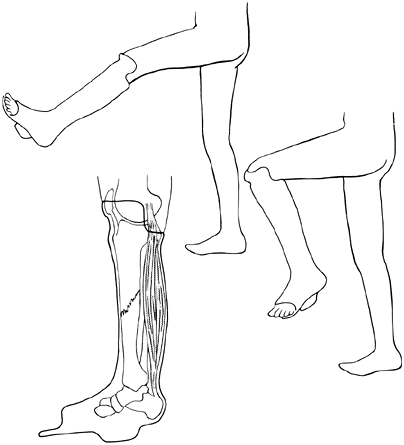

The below-the-knee total contact, or patellar tendon-bearing, cast is applied much as a regular short-leg walking cast is, with the following modifications (Fig. 7-9):

-

Keep the affected limb in a long-leg cast or a Jones compression splint until the swelling subsides (2–4 weeks).

-

Apply the cast padding to the lower leg and extend to 2 in. proximal to the superior pole of the patella.

-

First apply a short-leg cast and extend it to just inferior to the tibial tubercle. Sarmiento suggests molding the cast into a triangular shape,

with the sides of the triangle formed by the anterior tibial surface,

the lateral peroneal muscle mass, and the posterior aspect of the leg. -

Then have the assistant position the knee

in 40 to 45 degrees of flexion. The quadriceps muscles must be

completely relaxed. Use a 4-in. bandage of plaster to extend the cast

to the superior pole of the patella. Mold carefully

P.114

over

the medial tibial flare as well as into the patellar tendon and the

popliteal fossa. The lateral wings should be as high as possible. Trim

the posterior portion of the cast to one fingerbreadth or 1/2 in. below

the level of the cast indentation that was made anteriorly into the

patellar tendon. The posterior wall of the cast should be low enough to

allow 90 degrees of knee flexion without having the cast edge rub on

the hamstring tendons. These casts generally require the use of plaster

because of the critical molding involved, which is difficult with

fiberglass.![]() Figure 7-9. Completed below-the-knee total contact cast.

Figure 7-9. Completed below-the-knee total contact cast. -

If angulation

occurs at the fracture site with this cast, replace rather than wedge

the cast. If the patient ambulates well enough to maintain muscle bulk,

the original cast may not need to be replaced. -

Do not switch from a below-the-knee total contact cast to a regular short-leg cast

at some point midway in the healing phase of the fracture, because a

regular short-leg cast offers no rotational stability. Recent evidence

has shown that this type of cast is no more effective in immobilizing

tibia fractures than a standard short-leg cast (9).

-

-

The authors believe

that a long-leg weight-bearing cast is easier and safer (in regards to

skin and fracture complications) for most individuals to apply than the

below-the-knee total contact cast. Comparing the treatment

results published in the literature provides no evidence that one

technique is superior to the other. The theoretic advantage of

providing knee motion with the Sarmiento technique is offset by the

expertise required to apply this cast properly. -

Begin weight bearing

at 24 to 36 hours after plaster cast application when the patient can

tolerate it; patients with fiberglass casts can be encouraged to weight

bear 3 to 6 hours after casting.

-

-

Knee cast-brace

-

A cast-brace

is a casting device for the treatment of fractures of the distal femur

or tibial plateau, which are not considered appropriate for operative

management, generally in high-risk patients. Occasionally a cast-brace

is applied after 1 to 3 weeks of traction, with the patient remaining

in the hospital for a short period after the brace is applied. Thus,

the hospital stay can be as long as 2 to 4 weeks. In addition, this

technique allows mobility of the knee during the healing phase, so less

physical therapy is needed to regain knee motion when the fracture is

healed. These devices have generally been replaced by commercially

available hinged knee braces. -

Technique

-

Two people are required for application.

After the patient is lightly sedated, roll an elastic tubular stockinet

over the leg. While an assistant holds the leg, apply plaster over the

thigh to within 2 1/2 cm of the ischial tuberosity and the perineum.

Extend the plaster distally to the superior pole of the patella but

with enough clearance for full knee extension and flexion to 70

degrees. Then apply a short-leg cast. Make the plantar aspect of the

cast flat for ambulation in a walking shoe. -

Position two polycentric or cable knee hinge joints

2 cm posterior to the midline of the limb at the level of the abductor

tubercle. Use large hose clamps to secure the hinge joints to the cast

temporarily. A jig is helpful to keep these joints parallel. Evaluate

knee motion and make adjustments before securing the uprights with

plaster.-

If the roentgenograms show satisfactory alignment

of the fracture, start the patient on progressive ambulation with

“touch down” weight bearing. If a knee effusion develops, instruct the

patient to elevate the limb for 15 minutes of every hour. Once adequate

fracture consolidation is demonstrated, the patient can be encouraged

to bear weight. -

If the alignment of the fracture is not satisfactory,

remove the cast-brace and temporarily reinstitute traction treatment.

Consider continuing standard traction therapy, reattempting a

cast-brace again in 2 to 3 weeks, or performing internal fixation.

-

-

-

-

General techniques

-

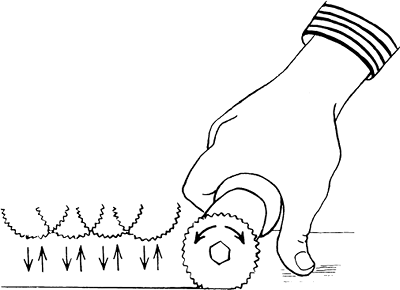

In removing or splitting casts, use the oscillating saw.

Reassure the patient by giving a cast saw demonstration before actually

cutting the cast. Stabilize the hand holding the electric saw on the

cast, and push the blade through just the plaster with short repetitive

strokes, as shown in Fig. 7-10. Avoid bony prominences as the cast saw can cut into the skin over them. -

Windows may

be cut from the cast to expose wounds. The windows must be replaced,

however, and rewrapped with either a new plaster or an elastic bandage

to prevent local edema.

-

-

Should unexpected swelling occur, bivalve the cast. Bivalving is superior to simply splitting the cast.

The technique consists of cutting the plaster as well as the cast

padding on both sides of the extremity. The anterior and posterior

parts of the cast can be held in place with bias-cut stockinet or an

elastic bandage. Advantages of this technique are that the anterior

half of the cast may be removed to inspect the compartments and that

complete anterior, posterior, and circumferential compression is

relieved. -

Splitting

a cast requires cutting a 1/2-in. strip of plaster from the full length

of the cast; otherwise, the proximal aspect of the plaster may act as a

circumferential tourniquet (2). Again, divide

the plaster and padding down to the skin because soft dressing might

also cause constriction. In the case of the lower extremity, the cast

is split anteriorly with a diamond-shaped section of plaster removed

from the anterior aspect of the ankle. Spread the cast for relief of

the symptoms. Pad the area with felt where the strip of plaster was

removed and overwrap with a rubber elastic bandage to avoid local

edema. This technique is not as satisfactory as bivalving a cast but is often appropriate for managing postoperative swelling.

-

Terminology

-

Use adhesive strapping

(taping) for the possible prevention and treatment of athletic

injuries. Use strips of adhesive tape instead of one continuous winding. -

Bandaging

(wrapping) uses nonadhesive materials (gauze, cotton cloth, and elastic

wrapping) in the treatment of athletic injuries. Employ one continuous

unwinding of material.

-

-

Adhesive strapping

-

Purposes of strapping

-

To protect and secure protective devices

-

To hold dressings in place

-

To limit motion

-

To support and stabilize

Figure 7-10. Saw-cutting technique that avoids skin laceration.

Figure 7-10. Saw-cutting technique that avoids skin laceration.

-

-

Construction factors

-

Tape grade

(backing material). Heavy backing materials have 85 longitudinal fibers

per square inch and 65 vertical fibers per square inch. Lighter grades

have 65 longitudinal fibers per square inch and 45 vertical fibers per

square inch. Store the tape in a cool, dry place. Keep the tape standing on end and not on its side. -

Adhesives.

Use a rubber-based spray-on adhesive primarily with athletes because

strength of backing, superior adhesion, and economy are needed. Use

acrylic adhesives in surgical dressing applications because a high

degree of backing and superior adhesion are not the primary

requirements.

-

-

Application and removal

-

Preparation

-

Clean the skin with soap and water and dry.

-

Remove all hair to prevent irritation.

-

Treat all cuts and wounds.

-

Apply a nonallergic skin adherent.

-

Position properly.

-

-

Size of tape

-

Use 1/4- to 1-in. tape on fingers, hands, and toes.

-

Use 11/4- or 11/2-in. tape on ankles, lower legs, forearms, and elbows.

-

Use 2- or 3-in. tape on large areas, knees, and thighs.

-

-

Rules of application

-

Avoid continuous strapping because this causes constriction. Use one turn at a time and tear after overlapping the starting end of the tape by 1 in.

-

Smooth and mold the tape as it is laid on the skin.

-

Overlap the tape at least one half its width over the tape below.

-

Allow the tape to fit the natural contour of the skin—that is, let it fall naturally and avoid bending around acute angles.

-

Keep the tape roll in one hand and tear it with the fingers.

-

Keep constant and even unwinding tension.

-

For best support, strap directly over the skin.

-

-

Techniques for removal

-

Remove the tape along the longitudinal axis rather than across it. If near a wound, pull toward the wound, not away from it.

-

Peel the tape back by holding the skin taut and pushing the skin away from the tape rather than by pulling the tape from the skin.

-

-

-

Skin reactions. Most tape reactions are mechanical,

not allergic. Allergic reactions are characterized by erythema, edema,

papules, and vesicles. Test for an allergic reaction by patch testing.

If the test is positive, the above signs manifest themselves within 24

to 48 hours.-

Mechanical irritation

is produced when tape is removed from the skin. It frequently occurs as

a result of shearing the skin when the tape is applied in tension or

used for maintaining traction. Such application induces vasodilation

and an intense reddening of the skin, which disappears shortly after

tape removal. The reaction is due to simple skin stripping—that is,

direct trauma to the outer skin layers resulting in loss of cells. -

Chemical irritation

occurs when components in adhesive mass or the backing of the tape

permeate the underlying tissues. This irritation is largely eliminated

through tape construction. -

Another irritative effect is localized inhibition of sweating, which is corrected by the use of nonocclusive (porous) tape.

-

P.116 -

-

Bandaging

-

Purposes of bandaging

-

Materials

-

Gauze, which holds dressings in place over wounds or acts as a protective layer for strapping

-

Cotton cloth for support wrapping or dressing

-

Elastic wrapping for compression wrapping or dressing

-

-

-

Medicated bandage

-

The medicated bandage (Unna boot) contains zinc oxide, calamine, glycerine, and gelatin and usually is indicated

for lower extremity areas of skin loss that require protection and

support. This type of support dressing prevents edema and allows

ambulation in patients with known venous conditions at the time of cast

removal. -

Application

-

Cleanse the area and position the ankle at a right angle.

-

Make a circular turn with the medicated bandage around the foot and direct the bandage obliquely over the heel. Then cut the bandage. This procedure ensures a flat surface.

-

Repeat until

the heel is adequately covered. Make the first layer snug and apply the

roll in a pressure-gradient manner; that is, apply the greatest

pressure distally with progressively diminishing pressure over the

upper leg. -

Do not reverse any turns

because the ridges formed may cause discomfort as the bandage hardens.

Overlap each turn one half of a preceding turn. Avoid winding the

bandage on too tightly. -

Cover the leg

approximately three times and extend the bandage 1 to 2 in. below the

knee; otherwise, the bandage may slip toward the ankle. Allow the

bandage to harden. Prevent soiling of clothing with gauze or stockinet

over the medicated bandage. Leave the bandage on for 3 to 7 days, and

repeat treatment if necessary.

-

-

-

Following cast removal

-

While the cast is still on,

range-of-motion exercises of the adjacent joints not immobilized and

isometric exercises for the immobilized muscles (e.g., weight bearing

in a cast) serve both to improve nutrition and to decrease atrophy of

articular cartilage, bone, and muscle. Edema and the rehabilitation

required after cast removal are also minimized. -

Warn the patient that after removal of any cast from a lower extremity, some swelling is normal.

-

Once the cast is removed, an elastic stocking or bandage is desirable for support.

-

Prescribe a specific exercise program to increase range of motion. Moist heat, such as a bath or whirlpool, may help mobilize the joint.

-

If swelling appears to be a problem, contrast baths

may be indicated (the 3-3-3 treatment): rest 3 minutes in cool water,

exercise 3 minutes in warm water, repeat 3 times; follow with 30

minutes of elevation. Repeat the entire process three times daily. -

Active exercise

is the key to success. Passive range-of-motion exercise too frequently

becomes a repeated manipulation. Manipulation under anesthesia is

occasionally necessary, but this should be followed with an aggressive

inpatient therapy program.

-

-

-

It is not always true that the sooner joints adjacent to a fracture are mobilized, the better the range of motion obtained. The following factors must be considered:

-

Fractures not involving articular surfaces

-

Joint movement is slow to return and poor in range if attempted movement produces pain, associated muscle spasm, and involuntary splinting.

-

Early joint movement can delay fracture healing if fixation is not rigid.

-

A normal joint tolerates longer periods of immobilization. The “safe” period of immobilization coincides well with the normal time necessary for

P.118

adjacent fracture healing. Only in the older patient with degenerative

changes in the joint is there a likelihood of intraarticular adhesions

and periarticular stiffening, even with short periods of immobilization. -

Some joints may tolerate immobilization better than others, but this presumption is not well documented.

-

Postinjury or postcasting edema is “glue.”

The area is soon infiltrated with young fibroblasts. Excessive

formation of collagen causes early and frequent permanent stiffness,

especially when collateral ligaments are immobilized in a shortened

position (e.g., metacarpophalangeal joints). -

Isometric exercises within the cast are recommended. Allow the muscles to move within the limits of the cast.

-

-

Fractures involving articular surfaces

-

Reduce intraarticular fractures anatomically if possible.

If operative intervention is indicated, then a goal of internal

fixation is to allow range-of-motion exercises or continuous passive

motion within the first 2 or 3 days postoperatively. -

If anatomic restitution cannot be achieved,

then early motion may allow mobile fragments to be molded into a better

position. This motion should improve the potential of fibrocartilage

resurfacing. Early movement is difficult to define, but some movement

should be started within the first week.

-

-

Between these two groups

is a considerable degree of overlap. If it is anticipated that a

complicated and often incomplete open reduction and internal fixation

is not secure enough to allow early movement of the joint, then it may

be better to treat the fracture nonoperatively. The objective is the best possible final range of movement.

-

JR, Frick SL, Skewes E, et al. Skin surface pressure beneath an

above-the-knee cast: plaster casts compared with fiberglass casts. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1997;79:565–569.