Ankle Fracture

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Ankle Fracture

Ankle Fracture

Simon C. Mears MD, PhD

Barry Waldman MD

Description

-

Fractures of the distal end of the fibula and tibia are termed ankle fractures.

-

Usually caused by the twisting of the body around a planted foot or a misstep that results in overstressing the ankle joint

-

Severe fractures may result in dislocation of the ankle.

-

-

2 fracture classification systems are used currently: Lauge-Hansen (1) and Weber (2) (or AO); each has disadvantages that prevent its use as a precise guide to treatment (3).

-

Lauge-Hansen system is based on foot position at the time of injury and force applied to it:

-

The 1st word in the classification refers to position and the 2nd is the force applied.

-

The 4 main types are supination-external rotation, supination-adduction, pronation-external rotation, and pronation-abduction.

-

-

The Weber or AO system is simpler, and based on the level of the fibular fracture:

-

A, below the ankle-joint line

-

B, at the joint line

-

C, above the joint line

-

-

-

A tibial plafond, or pilon, fracture is a

comminuted fracture of the distal end of the tibia that is caused by

high-energy trauma (see “Tibial Plafond Fracture”).

Epidemiology

Incidence

-

Ankle fractures are the 2nd or 3rd most common type of fracture (4).

-

Fractures in children typically involve the growth plate.

-

Fractures in adolescents (Tillaux fractures) can have special patterns because of the partial closure of the growth plates (5).

Risk Factors

Fracture rates are thought to be highest in young adults (6).

Etiology

-

Most often, ankle fractures result from acute trauma, such as a fall, misstep, or sports injury.

-

Rarely caused by a pathologic lesion

Associated Conditions

-

Ankle sprain

-

PTT sprain

Signs and Symptoms

-

Pain in the ankle and inability to bear weight

-

Deformity may be present with a fracture/dislocation.

-

Swelling and ecchymosis are common.

Physical Exam

-

Palpate the affected area and inspect for any breaks in the skin or tenting.

-

Check the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses and all motor and sensory nerves to the foot.

-

Inversion injury of the ankle can cause peroneal nerve palsy (7).

-

-

Examine for severe swelling and compartment syndrome in the lower leg and foot.

Tests

Lab

Generally, testing is for preoperative evaluation only.

Imaging

-

Radiography:

-

Although a tendency exists to obtain

radiographs of the ankle of any patient who complains of pain and

swelling, limiting radiography to those ankles with specific

indications reduces radiograph usage by 50% without missing any

clinically significant fractures (8).-

These indications are called the Ottawa

ankle rules and include gross deformity, instability of the ankle,

crepitus, localized bone tenderness, swelling, and inability to bear

weight (9).

-

-

3 radiographic views of the ankle are

obtained: An AP view, a lateral view, and 15° internally rotated

oblique view (called a mortise view). -

Stress views are helpful in evaluating

ligamentous injuries and should be obtained in patients with evidence

of fibular fracture without medial malleolar fracture (10).

-

-

Patients with severely comminuted intra-articular fractures may benefit from a CT scan.

Differential Diagnosis

-

Ligamentous injury (sprain) resulting from acute trauma and is not evident on a radiograph

-

Stress fractures of the distal fibula

-

Osteochondritis dissecans

-

Metatarsal fracture

General Measures

-

Pain medication and elevation should be prescribed.

-

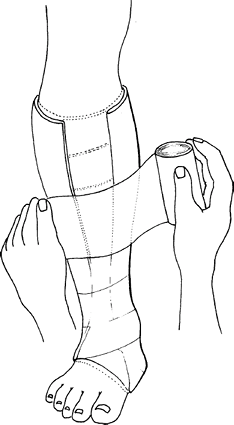

All ankle fractures should be splinted in a neutral position acutely (Fig. 1).

-

Isolated fibular fractures or undisplaced fractures of the medial malleolus may be treated in a below-the-knee cast.

-

Stable fractures should be treated functionally with an air splint and gradual advancement of weightbearing.

-

Congruity of the ankle joint is thought to be important in reducing the incidence of posttraumatic arthritis.

-

Dislocations should be reduced with adequate sedation as soon as possible.

-

Patients with open fractures should be

taken to the operating room for irrigation, débridement, and fixation

within 6–8 hours of the injury. -

Patients should be kept nonweightbearing

on the affected side until pain has subsided and some signs of fracture

healing appear on follow-up radiographs. -

Bimalleolar fractures or fibular fractures with medial ligament injury or syndesmotic injury are treated surgically.

Activity

-

The ankle should be elevated to reduce swelling.

-

Early weightbearing and ROM are important to prevent stiffness.

Nursing

Care should be taken to avoid rubbing on the splint or cast.

|

|

Fig.

1. Ankle fractures or other injuries may be splinted by a “sugar tong” method of using a layer of padding, fiberglass, or plaster and an elastic (Ace) bandage. |

P.19

Special Therapy

Physical Therapy

ROM of the MTP joints and, later, of the ankle and

midfoot are important to prevent contractures and to reduce scarring of

soft tissues.

midfoot are important to prevent contractures and to reduce scarring of

soft tissues.

Medication (Drugs)

First Line

Analgesics

Surgery

-

Fractures of the ankle that are displaced or unstable generally are treated surgically:

-

Bi- or trimalleolar ankle fractures

-

Distal fibular fractures with medial ligament injury

-

Fibular fractures with syndesmotic injury

-

Medial malleolar fractures

-

Open fractures

-

-

A determination of medial injury should be made with an external rotation stress view of the ankle (11,12).

-

The fibular fracture usually is plated through a lateral incision (either a lateral plate or a posterior antiglide plate) (13).

-

Medial malleolar fractures are stabilized with compression screws.

-

A buttress plate is used for unstable vertical fractures.

-

-

A syndesmotic injury that is unstable under fluoroscopic testing should be treated with syndesmotic screw fixation.

-

Open or unstable fractures may require an external fixator with or without internal fixation.

-

A patient should have a follow-up visit at 1–2 weeks to check radiographs.

-

After the initial splint is removed, patients are placed in a below-the-knee cast or moon boot for 4 weeks.

-

Radiographs are obtained and assessed at 6-week intervals until fracture healing.

Disposition

Issues for Referral

Unstable or displaced fractures should be referred to an orthopaedic surgeon.

Prognosis

Most ankle fractures heal without incident, and the patient is able to return to normal activities (14).

Complications

-

With severe fractures, blisters may occur and may compromise skin integrity.

-

Peroneal tendon lesions can be caused by posterior antiglide plates (15).

-

Painful hardware may necessitate its removal after fracture healing.

-

Compartment syndrome

-

Open fractures may become infected and may require irrigation and débridement.

-

Nonunion, often requiring fusion surgery

-

Malunion, sometimes requiring corrective osteotomy

-

Elderly patients:

-

May have osteoporotic bone, which makes surgery more difficult

-

Are at higher risk for skin or wound breakdown, and special care must be taken to ensure the blood supply (16)

-

-

Posttraumatic arthritis:

-

Occurs in 25% of patients with displaced ankle fractures and may require ankle fusion (17)

-

The number of patients with ankle pain and arthritic changes seems to increase with the length of follow-up after fracture (17).

-

Patient Monitoring

Radiographs should be taken every 2–6 weeks, depending on the fracture pattern and signs of healing.

References

1. Lauge-Hansen N. Fractures of the ankle. II. Combined experimental-surgical and experimental-roentgenologic investigations. Arch Surg 1950;60:957–985.

2. Weber BG. Die Verletzungen des oberen Sprunggelenkes. Bern: Verlag Hans Huber, 1966.

3. Whittle

AP, Wood GW, II. Fractures of lower extremity. In: Canale ST, ed.

Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 10th ed. St. Louis: Mosby,

2003:2725–2872.

AP, Wood GW, II. Fractures of lower extremity. In: Canale ST, ed.

Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 10th ed. St. Louis: Mosby,

2003:2725–2872.

4. van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HGM, et al. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone 2001;29:517–522.

5. Kay RM, Matthys GA. Pediatric ankle fractures: evaluation and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2001;9:268–278.

6. Hasselman CT, Vogt MT, Stone KL, et al. Foot and ankle fractures in elderly white women. Incidence and risk factors. J Bone Joint Surg 2003;85A:820–824.

7. Redfern DJ, Sauve PS, Sakellariou A. Investigation of incidence of superficial peroneal nerve injury following ankle fracture. Foot Ankle Int 2003;24:771–774.

8. Bachmann

LM, Kolb E, Koller MT, et al. Accuracy of Ottawa ankle rules to exclude

fractures of the ankle and mid-foot: systematic review. Br Med J 2003;326:1–7.

LM, Kolb E, Koller MT, et al. Accuracy of Ottawa ankle rules to exclude

fractures of the ankle and mid-foot: systematic review. Br Med J 2003;326:1–7.

9. Stiell

IG, Greenberg GH, McKnight RD, et al. Decision rules for the use of

radiography in acute ankle injuries. Refinement and prospective

validation. JAMA 1993;269:1127–1132.

IG, Greenberg GH, McKnight RD, et al. Decision rules for the use of

radiography in acute ankle injuries. Refinement and prospective

validation. JAMA 1993;269:1127–1132.

10. Egol

KA, Amirtharage M, Tejwani NC, et al. Ankle stress test for predicting

the need for surgical fixation of isolated fibular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg 2004;86A:2393–2398.

KA, Amirtharage M, Tejwani NC, et al. Ankle stress test for predicting

the need for surgical fixation of isolated fibular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg 2004;86A:2393–2398.

11. Egol KA, Tejwani NC, Walsh MG, et al. Predictors of short-term functional outcome following ankle fracture surgery. J Bone Joint Surg 2006;88A:974–979.

12. McConnell T, Creevy W, Tornetta P, III. Stress examination of supination external rotation-type fibular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg 2004;86A:2171–2178.

13. Lamontagne

J, Blachut PA, Broekhuyse HM, et al. Surgical treatment of a displaced

lateral malleolus fracture: the antiglide technique versus lateral

plate fixation. J Orthop Trauma 2002;16:498–502.

J, Blachut PA, Broekhuyse HM, et al. Surgical treatment of a displaced

lateral malleolus fracture: the antiglide technique versus lateral

plate fixation. J Orthop Trauma 2002;16:498–502.

14. Bhandari

M, Sprague S, Hanson B, et al. Health-related quality of life following

operative treatment of unstable ankle fractures: a prospective

observational study. J Orthop Trauma 2004;18:338–345.

M, Sprague S, Hanson B, et al. Health-related quality of life following

operative treatment of unstable ankle fractures: a prospective

observational study. J Orthop Trauma 2004;18:338–345.

15. Weber

M, Krause F. Peroneal tendon lesions caused by antiglide plates used

for fixation of lateral malleolar fractures: the effect of plate and

screw position. Foot Ankle Int 2005;26:281–285.

M, Krause F. Peroneal tendon lesions caused by antiglide plates used

for fixation of lateral malleolar fractures: the effect of plate and

screw position. Foot Ankle Int 2005;26:281–285.

16. Kettunen J, Kroger H. Surgical treatment of ankle and foot fractures in the elderly. Osteoporos Int 2005;16:S103–S106.

17. Day GA, Swanson CE, Hulcombe BG. Operative treatment of ankle fractures: a minimum ten-year follow-up. Foot Ankle Int 2001;22:102–106.

Additional Reading

Takao

M, Uchio Y, Naito K, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of combined

intra-articular disorders in acute distal fibular fractures. J Trauma 2004;57:1303–1307.

M, Uchio Y, Naito K, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of combined

intra-articular disorders in acute distal fibular fractures. J Trauma 2004;57:1303–1307.

Codes

ICD9-CM

824.9 Fracture, ankle

Patient Teaching

Patients should be aware of the potential for posttraumatic arthritis later in life.

Prevention

Avoidance of irregular walking and running surfaces

FAQ

Q: How long does it take to recover from an ankle fracture?

A:

Patients make substantial improvement in function in the first 6 months

after injury. Evaluations of patients’ driving skills after fracture

fixation have shown that the use of car brakes returns to normal at 9

weeks after fracture. Overall recovery continues up to a year and is

slower for elderly patients.

Patients make substantial improvement in function in the first 6 months

after injury. Evaluations of patients’ driving skills after fracture

fixation have shown that the use of car brakes returns to normal at 9

weeks after fracture. Overall recovery continues up to a year and is

slower for elderly patients.