Principles of Sonography

and 13 MHz. The average wave length in this band is about 1 mm. This

limits the resolution to structures that are larger than 1 mm. Most

nerves of interest range in size from 2 mm to 10 mm. Veins and arteries

of interest are typically 3 mm to 15 mm.

the ultrasound image. In general, higher frequency probes generate

higher resolution images. Unfortunately, high frequency ultrasound

waves (8 MHz to 13 MHz) are rapidly attenuated in tissue so that high

frequency probes are best suited for structures less than 5 cm deep to

the skin.

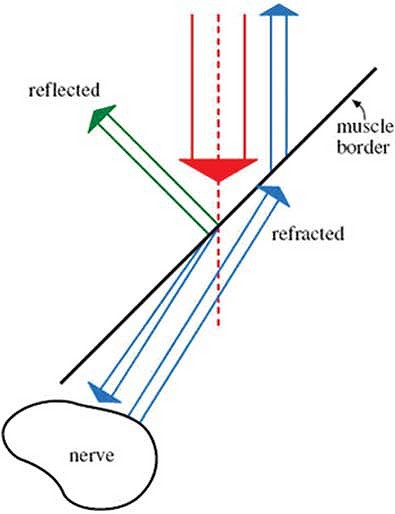

through tissue. When this occurs, a nerve or other organ may appear at

a different anatomical location than its actual site. This is the same

phenomenon responsible for the apparent bending of your forearm when

you place it in a bucket of water (Fig. 32-1).

Fat globules below the skin, in the muscle and around nerves are about

1 mm in diameter. These globules serve as diffraction sites for the

incident and reflected ultrasound beam and cause a speckled appearance

in the image (Fig. 32-2).

Fat is also extremely efficient at absorbing ultrasound so that little

of the beam is returned to the receiver. For these reasons, obese

patients can be very difficult to image.

sensitive to the angle of incidence of the beam relative to the nerve.

Sometimes changing the angle of incidence by only a few degrees can

bring the nerve into focus. This phenomenon is thought to be caused by

diffraction of the type described above.

(gain) of the entire image or more superficial (near field) and deep

(far field) structures. Increasing the gain makes the entire image

whiter. Increasing the gain too much creates a snowy background whereby

all of the structures become indistinguishable. In general, the gain

should be set so that most of the background is black and only the

structures of interest, such as nerves and vessels, are easily seen.

Modern machines also allow the user to adjust the contrast. The formal

term for contrast is dynamic range compression.

Increasing the dynamic range compression makes the white images whiter

and the black images blacker. This may bring the edges of anatomic

structure into better view. Decreasing the dynamic range compression

makes everything look grey.

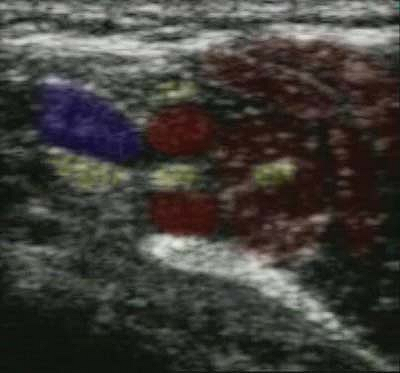

nature. Veins can be distinguished by their compressibility. Pressing

on the skin with the probe will usually cause the

vein

to collapse. Color flow Doppler imaging can also be used to identify

and distinguish arteries and veins. By convention, blood flowing toward

the probe is colored red. Blood flowing away from the probe is colored

blue. Blood flowing perpendicular to the probe remains black. Velocity

gates can be set to measure the flow velocity. High velocities are

usually arteries. Low velocities are usually veins.

|

|

Figure 32-1. Ultrasound beam refracting as it passes through tissue.

|

|

|

Figure 32-2.

Fat globules below the skin serve as diffraction sites for the incident and reflected ultrasound beam and cause a speckled appearance in the image. |

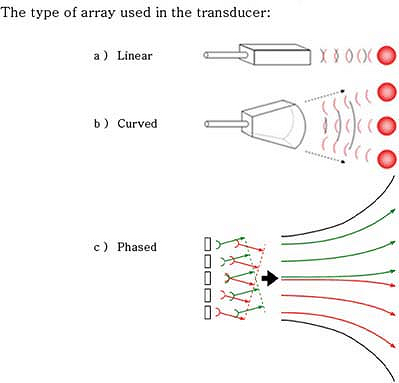

arrays create wedge-shaped images and are most useful for deeper

structures. Because the beam disperses in a curved array, its

resolution is usually lower than a linear array. A phased array retains

the elements in a straight line. But the elements fire in sequence

creating a phase delay between each element. The net result is a

wedge-shaped image from a set of linear transducers. Because this

signal is averaged, its resolution is also lower than a standard linear

array.

|

|

Figure 32-3. Transducer elements can be arranged in linear or curved arrays.

|

amplitude of their ultrasound wave at a specific fundamental frequency.

Harmonics of this frequency are also emitted at lower amplitudes. By

listening for the echo at these higher harmonic frequencies, image

resolution can be enhanced. Because the harmonics are very low

amplitude, only transducers that have sufficient power output can be

used for harmonic imaging. This type of image enhancement is referred

to as tissue harmonic imaging.

elements in the probe are used as both transmitters and receivers. The

transducer elements emit a short ultrasound burst and then wait for the

echo before emitting another ultrasound burst. This allows the probe to

be smaller compared with continuous wave probes where there are

separate emitters and transducers.

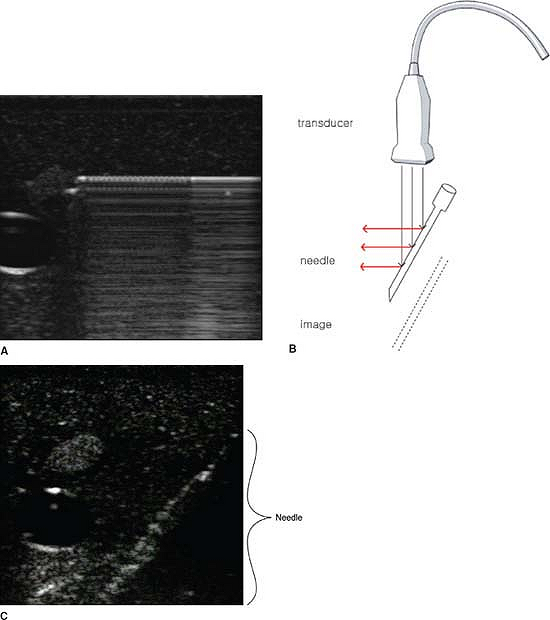

the ultrasound beam, it is a good reflector and it is easy to image. In

some cases, it may be necessary to insert the needle nearly parallel to

the beam in order to reach the targeted organ. In this case, most of

the echo is lost and the needle image is much fainter. Ghosts on the

deep side of the needle are cause by the needle vibrating itself (Fig. 32-4A).

These reverberations return to the receiver later than the first volley

of echoes. For this reason, they are seen as deeper in the tissue (Fig. 32-4B, 4C).

The reasons for this dichotomy are not known, but it may be related to

the depth of the nerves and the relative amounts of fat and stroma

within the nerves themselves. On ultrasound cross section, nerves are

round, hypo- or hyperechoic, reticulated structures. When imaged along

their long axis, nerves appear as linear, hypo- or hyperechoic streaks,

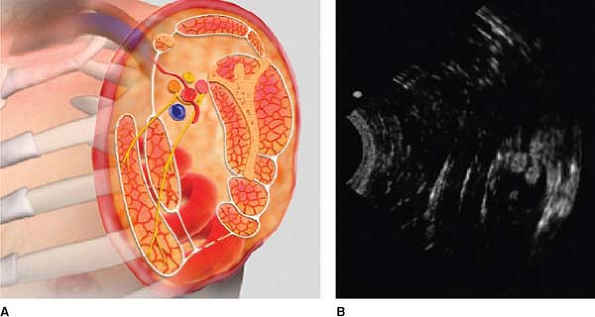

on ultrasound. Bones are hyperechoic and usually very bright white (Fig. 32-2). Arteries and veins are black unless color flow Doppler imaging is used (Fig. 32-6B).

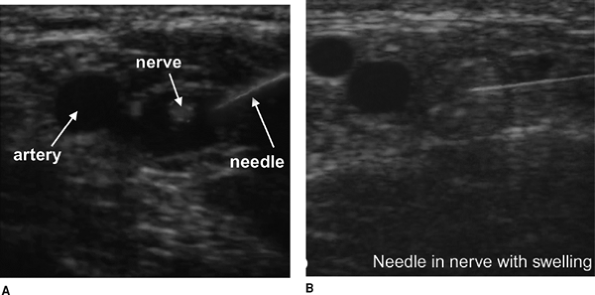

usually a potential space between the fascia and the epineurium. When a

needle punctures the fascia, local anesthetic can usually be deposited

between the fascia and nerve. This creates a black (hypoechoic) ring

around the nerve. In some cases the fascia adheres to the epineurium or

is missing. In that case, the needle may puncture the nerve and the

nerve will swell as the local anesthetic is injected (Fig. 32-7A, B).

-

Stimulation with the peripheral nerve

stimulator is not necessary if the operator is certain of the nerve’s

identity on ultrasound. When the stimulator is used, it need only be

used to confirm the target nerve, and can then be turned off. Because

the local anesthetic is injected around the target nerve under

ultrasound visualization, there is no need to “titrate” the current to

the twitch. -

It is challenging to keep the needle

perfectly parallel to the long axis of the transducer. Frequent fine

adjustment of the transducer may be necessary, along with switching the

line of site of the operator from the ultrasound unit screen to the

site of needle insertion. -

As local anesthetic is injected, each

increment should cause visible expansion of the tissues at the tip of

the needle. This provides evidence that the tip of the needle is

neither intravascular nor intraneural. -

If all of the local anesthetic solution

seems to accumulate on only one side of the target nerve, the needle

should be gently advanced or moved to another site around the

P.274P.275P.276

nerve,

to allow accumulation of the solution around the entire nerve (the

“halo” effect). This optimizes block set-up time. It should be clear

that each increment of subsequent local anesthetic injection causes

distension of the tissues at the tip of the needle. It is not necessary

to restimulate at each site, but the patient should be assessed for

paresthesia or pain in the territory of the stimulated nerve. Figure 32-4.

Figure 32-4.

Ghosts on the deep side of the needle cause reverberations to return to

the receiver later than the first valley of echoes causing them to be

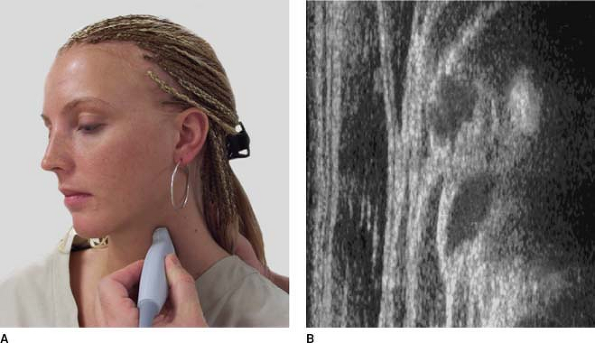

seen deeper in the tissue.![]() Figure 32-5. Above the collar bone, nerves are usually dark (hypoechoic).

Figure 32-5. Above the collar bone, nerves are usually dark (hypoechoic). Figure 32-6. Nerves located below the collar bone are usually white (hyperechoic).

Figure 32-6. Nerves located below the collar bone are usually white (hyperechoic).![]() Figure 32-7.

Figure 32-7.

When a needle punctures the fascia, local anesthetic can usually be

deposited between the fascia and nerve. This creates a black

(hypoechoic) ring around the nerve. -

As with any block guided by the nerve

stimulator, mild “pressure paresthesias” are sometimes evident during

injection of local anesthetic in blocks carried out by ultrasound

guidance. This should be differentiated from the severe pain of

intrafascicular injection.