Examination of the Dizzy Patient

– Neurologic Examination in Common Clinical Scenarios > Chapter 44 –

Examination of the Dizzy Patient

patient with dizziness is to determine whether the patient’s dizziness

is actually due to lightheadedness, imbalance, or vertigo, paving the

way for the most appropriate further investigation and treatment.

-

Lightheadedness implies a sensation of impending loss of consciousness, also called presyncope.

Episodic lightheadedness suggests episodes of global cerebral

hypoperfusion, such as from cardiac causes or orthostatic hypotension. -

Imbalance is

a sensation of gait instability (disequilibrium) that may range from

subtle to severe. Patients may especially interpret their imbalance as

“dizziness” when their gait dysfunction is subtle, because they may be

unaware that their feeling is really an imbalanced sensation. -

Vertigo

refers to an illusory sensation of motion. Most patients with vertigo

describe a feeling of rotation of the environment or in their head, but

vertigo can also include any feeling of movement, such as a feeling of

tilting or swaying. Vertigo occurs due to disorders of the vestibular

system, either peripheral (the inner ear or the vestibular nerve) or

central (brainstem or cerebellum).

the main goal of the history is to try to determine what the patient

means by “dizzy.” The first step is to simply ask the patient, “What do

you mean by dizzy?” Let the patient tell you, in his or her own words,

what he or she means, and try to avoid putting words in the patient’s

mouth. Additional clues to the cause of dizziness that can be gleaned

by the history alone are listed below.

-

Patients with lightheadedness

(presyncope) usually can describe their feeling as that of

“lightheadedness” or a feeling “like I might pass out.” A history of

any of the episodes progressing to true loss of consciousness is

further evidence that the patient’s symptoms fit into this category of

dizziness. -

Ask about any associated cardiac

symptoms, such as palpitations or chest pain, although the absence of

these symptoms does not exclude a cardiac cause. -

Lightheadedness occurring only after standing suggests orthostatic hypotension.

-

Patients with imbalance as the cause of

their dizziness usually can describe their feeling as something like an

“off-balanced” or “unsteady” sensation, and they should be symptomatic

when standing or walking but not when lying or sitting. -

The historical finding of worsened

imbalance when standing in the dark (e.g., walking to the bathroom at

night) or with eyes closed (e.g., in the shower) suggests

proprioceptive dysfunction. Even in the absence of a positive Romberg

test, these historical clues are strongly suggestive of proprioceptive

problems, such as can occur due to peripheral neuropathies or spinal

cord (posterior column) problems.

-

Patients with vertigo usually can describe their feeling as that of a spinning, moving, or tilting sensation.

-

Ask about any associated brainstem

symptoms, such as double vision, or numbness or weakness of the face or

of the extremities. The presence of brainstem symptoms in patients with

vertigo is strongly suggestive of brainstem dysfunction (e.g.,

ischemia) as the cause; their absence, however, doesn’t exclude the

possibility of a central (brainstem or cerebellar) cause of vertigo. -

Hearing complaints, such as unilateral

hearing loss or tinnitus, occurring in association with vertigo suggest

a peripheral labyrinthine disorder. -

Paroxysmal vertigo brought on by changes

in head position, such as when turning, bending over, or rolling over

in bed, is highly suggestive of the clinical syndrome of benign

paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), which occurs due to the presence

of calcium carbonate crystals floating in one of the semicircular

canals. -

Nausea and vomiting is a nonspecific accompaniment of vertigo and can occur with vertigo of peripheral or central etiologies.

pretty good idea whether your patient’s dizziness is due to

lightheadedness, imbalance, or vertigo. The examination is then

performed to find evidence to support or refute your hypothesis and

provide further information regarding possible etiologies. Listed below

are specific examination elements, depending on your clinical

suspicion, that can be helpful.

-

In the patient with episodic

lightheadedness, be certain (as in any new patient visit) to obtain

your patient’s blood pressure and pulse, and also perform a bedside

cardiac examination. -

Check lying and standing blood pressure in any patient whose symptoms suggest the possibility of orthostatic hypotension:

-

Have the patient lie flat in bed for a few minutes, then check the patient’s supine blood pressure and pulse.

-

Ask the patient to stand. (It’s usually

not necessary to check a sitting blood pressure and pulse, unless the

patient can’t tolerate the standing position.) -

After the patient has been upright for approximately 2 to 3 minutes, check the patient’s standing blood pressure and pulse.

-

-

A standing decrease in systolic blood

pressure by 20 mm Hg or more is consistent with orthostatic

hypotension; there may or may not be an increase in pulse depending on

the cause. Patients whose orthostasis is due to volume depletion would

be expected to have the ability to mount a tachycardic response to the

blood pressure drop; however, patients with autonomic insufficiency may

have profound orthostatic drops in blood pressure with little or no

increase in pulse rate. When orthostatic hypotension is found, it is

also important to ask the patient if any symptoms during the test

re-created his or her presenting complaints.

-

In the patient with possible imbalance as

the cause of dizziness, pay particular attention to assessing gait and

look for abnormalities of motor, sensory, or cerebellar function. -

Look for proprioceptive loss in the toes or a Romberg sign (see Chapter 32,

Romberg Testing); however, it is more common to discover subtle

Romberg-like findings by history (worsened imbalance in the dark or in

the shower) than to detect proprioceptive loss or a Romberg sign on

examination. Often, the only examination clue to neuropathic or

posterior column dysfunction is vibratory loss in the feet.

-

Patients with vertigo due to acute

cerebellar or brainstem dysfunction may have significant gait ataxia

and may even be unable to walk without assistance (see Chapter 39, Examination of Gait). -

Patients with peripheral vestibular

disorders may have some difficulty with gait, particularly while

acutely vertiginous, but usually not with the severity of some patients

with an acute central (e.g., cerebellar) process. Patients with

vestibular problems may feel pulled and lean toward the side of the

vestibular dysfunction, but they can still usually walk without a

significant problem. -

Nystagmus may be seen with vertigo of

central or peripheral origin. Depending on the cause and severity of

the problem, nystagmus can be seen in primary gaze (i.e., while the

patient is looking forward) or when eye movements are examined (i.e.,

in horizontal or vertical gaze). Features of nystagmus that are

suggestive of central versus peripheral labyrinthine disorders are

summarized in Table 44-1. The most important

discriminating feature of nystagmus is that purely vertical nystagmus

is strongly suggestive of central (cerebellum or brainstem) causes of

vertigo. -

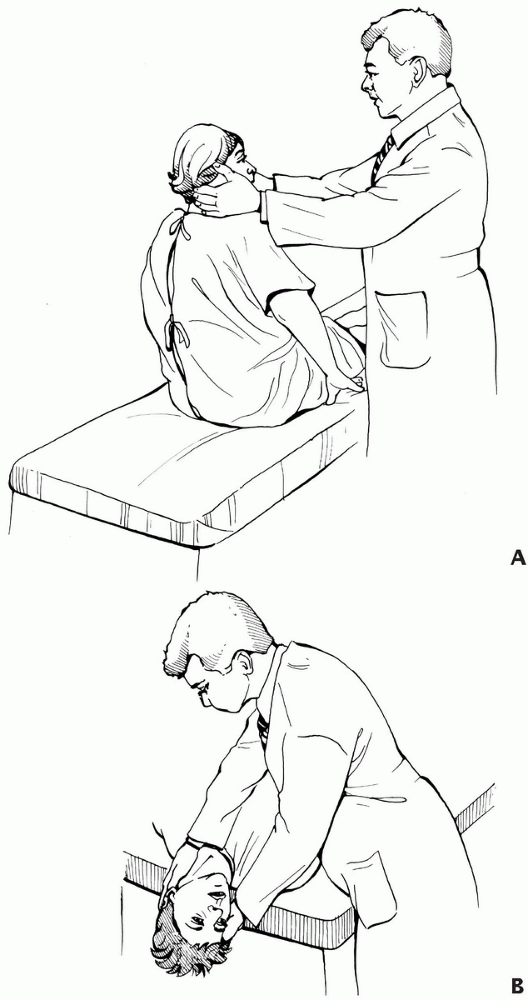

Patients whose clinical symptoms suggest BPPV should undergo positional testing with the Dix-Hallpike test (Fig. 44-1). The purpose of the Dix-Hallpike test (also called the Bárány maneuver or the Nylen-Bárány maneuver)

is to look specifically for evidence to support the diagnosis of BPPV

in patients who are clinically suspected of having this syndrome based

on the history. It is not a general test of vestibular function. To

perform the Dix-Hallpike test:-

Inform the patient that you’ll be

attempting to produce the patient’s vertigo with the maneuver, ask the

patient to try to keep his or her eyes open throughout, and explain the

procedure to the patient. -

Have the patient sit up on the examining

table (or in bed). Make sure the patient is sitting in a position that

will allow the head to be extended off of the table when the patient

lies down. -

Turn the patient’s head to the side

(right or left) that you think is most likely, by history, to produce

vertigo when the patient lies down [i.e., if

P.150

the

patient says that turning his or her head to the right in bed usually

provokes vertigo, test the patient initially with the head to the right

(Fig. 44-1A)].TABLE 44-1 Features of Nystagmus of Central versus Peripheral OriginLocalization of

Acute DysfunctionType of Nystagmus

That May Be PresentDirection of Nystagmusa in Relation to

Direction of GazeCentral (cerebellum or brainstem)

Vertical or horizontal; may have rotatory component

Nystagmus may

change direction with change in direction of gaze (e.g., nystagmus may

be left-beating with gaze to the left and right-beating with gaze to

the right)bPeripheral (labyrinth)

Usually horizontal; may have rotatory component

Although

nystagmus might only be present when looking in one direction, if it is

present in both left and right gaze, the nystagmus always beats in the

same direction; peripheral nystagmus is most prominent when gazing in

the direction of fast phaseca The direction of nystagmus is named after the fast phase (the direction it is beating in).

b

The finding of changing direction of nystagmus with change in gaze is

only helpful in supporting a central origin when present; acute

cerebellar disorders may cause nystagmus in only one direction of gaze,

appearing similar to peripheral nystagmus.c In peripheral vestibular disorders, the direction of the slow phase points to the side of the vestibular lesion.

Adapted from Hotson JR, Baloh RW. Acute vestibular syndrome. N Engl J Med 1998;339:680-685.

-

While holding the patient’s head in your

hands, rapidly move the patient down to the head-hanging position, all

the while keeping his or her head turned to the side (Fig. 44-1B). -

Observe the patient in that position for

at least 10 seconds, watching for a complaint of vertigo. Look at the

patient’s eyes for nystagmus during this time, especially during any

complaint of vertigo. You don’t need to check eye movements; just

observe the open eyes for the presence of nystagmus. -

Sit the patient back up.

-

If the initial maneuver brought on

vertigo, consider performing the maneuver again, looking for the

typical extinction of the response with repeat testing; however, this

additional confirmation is usually not necessary. -

If the initial maneuver did not bring on

vertigo, sit the patient back up and repeat the procedure with the head

turned in the opposite direction.

-

-

Characteristic abnormalities on the Dix-Hallpike maneuver supportive of a diagnosis of BPPV include the following:

-

Recapitulation of the patient’s symptoms

of positional vertigo, typically lasting up to approximately 30

seconds. The vertigo experienced by patients with BPPV during the

Dix-Hallpike maneuver is usually not subtle; patients with this

syndrome are often distressed by the vertigo evoked by this test. -

A characteristic latency to the onset of the vertigo (and nystagmus) that may be delayed up to 10 seconds.P.151

Figure 44-1

Figure 44-1

Dix-Hallpike testing for benign positional vertigo with the head to the

right. See text for details. (Redrawn from Furman JM, Cass SP. Benign

paroxysmal positional vertigo. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1590-1596.) -

A burst of primarily rotatory (eye

rotating toward the dependent ear) nystagmus during the vertigo. The

finding of nystagmus, however, although supportive, is of lesser

diagnostic importance than the vertigo brought on during the maneuver;

this is mainly because it’s often hard to visualize the eyes during the

patient’s distress. -

Extinction of the response [i.e., if the

procedure is repeated with the head turned in the same direction, the

vertigo (and nystagmus) is less severe].

-

acute vertigo is not always easy on the basis of the history and

examination. The finding of brainstem dysfunction or purely vertical

nystagmus strongly supports a central cause, but their absence does not

exclude a central (e.g., acute cerebellar) process.