SOFT-TISSUE SARCOMAS AND BENIGN SOFT-TISSUE TUMORS OF THE EXTREMITIES

VII – NEOPLASTIC, INFECTIOUS, NEUROLOGIC AND OTHER SKELETAL DISORDERS

> Tumors and Tumor-Like Conditions > CHAPTER 129 – SOFT-TISSUE

SARCOMAS AND BENIGN SOFT-TISSUE TUMORS OF THE EXTREMITIES

University of Chicago Hospitals and Clinics, Department of Surgery,

Section of Orthopaedic Surgery and Rehabilitation Medicine, Chicago,

Illinois, 60637.

the extremities are a common physical finding. Whereas most are

posttraumatic or inflammatory in nature, a certain number later prove

to be benign or malignant soft-tissue neoplasms. Soft-tissue masses

present a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to the treating surgeon.

Some require only observation, whereas others should be imaged with

appropriate methods and subsequently undergo pathologic evaluation. The

difficulty is knowing what features of the patient’s soft-tissue

mass—for example, size, depth, or texture—are important in

differentiating benign from malignant disease. A consistent,

comprehensive, and educated approach to the evaluation and treatment of

a soft-tissue mass will allow the surgeon to overcome this difficulty

and provide optimal care as well as avoid an inaccurate diagnosis and

excessive or inadequate treatment.

of value. Cognitive and emotional issues, especially anxiety, denial,

or ignorance, often cloud a patient’s memory and reporting of events

related to the tumor. Patients usually are unable to give an accurate

estimate as to how long the mass has been present or its growth

characteristics. Often, there is a history of trauma to the region that

has brought the mass to the patient’s attention. Symptoms may or may

not be present in both malignant and benign tumors; however, you are

more likely to investigate and eventually treat masses that are

symptomatic.

diagnosis, except for patients with multifocal disease or those who

have an established clinical syndrome. Exceptions include a familial

history of lipomatosis, neurofibromatosis, Gardner’s syndrome (colonic

polyposis and desmoid tumor), Li-Fraumeni syndrome (familial breast

cancer and soft-tissue sarcoma) (16), and Maffucci’s disease (hemangiomas noted in conjunction with multiple bone enchondromas).

diagnostic. Tumor size, depth, and consistency can only be approximated

in all but very small subcutaneous masses. It is uncommon for a mass to

be pulsatile, indicating an underlying vascular neoplasm, or for

Tinel’s sign to be present in association with peripheral nerve sheath

tumors.

evaluation of a patient with a soft-tissue mass is discerning which

lesions should simply be observed and which should undergo further

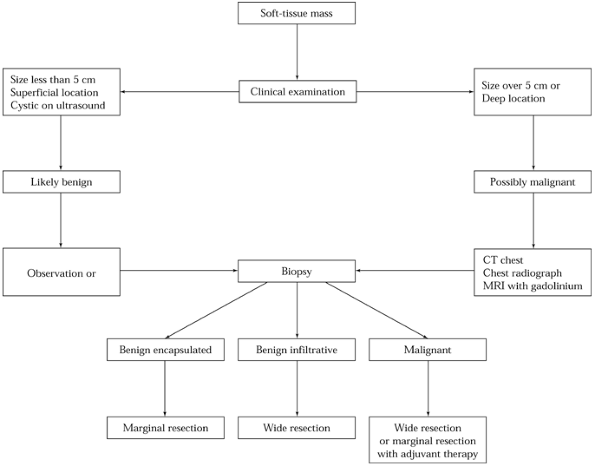

evaluation with imaging studies and possible biopsy. A suggested

strategy is delineated in Figure 129.1 (19). As can be seen, tumor size and tumor depth are important features (18,24). Large or deep tumors should be considered malignant until imaging studies or biopsy prove otherwise.

|

|

Figure 129.1. Flow diagram of a suggested strategy for the evaluation and treatment of a patient with a soft-tissue mass.

|

are rarely diagnostic. Occasionally, a relative radiolucency is seen in

the soft tissues compared with the surrounding tissues. This would

suggest the presence of fat and an intramuscular lipoma. Phleboliths

may be seen with hemangiomas; however, other forms of mineralization in

the form of calcification or ossification are nonspecific and may

suggest either underlying myositis ossificans, atypical infection

(parasitic), or synovial sarcoma.

helpful in locations about joints (ganglion or popliteal cysts) and in

the evaluation of the fluid content of a soft-tissue mass. Purely

cystic masses are not likely to be malignant. Ultrasound is also useful

in guiding the performance of an aspiration or biopsy, with cyst

contents sent for cytologic evaluation.

can be observed at intervals of several months to detect any change in

size. Even if the underlying lesion proves to be malignant, the

prognosis for survival as well as for local control is excellent (20,30).

If the mass grows or symptoms develop, perform a magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) scan, followed by biopsy and possible excision.

the extremities. If the mass has signal characteristics identical to

those of subcutaneous fat on all sequences and does not enhance with

gadolinium, it is most likely to be a lipoma. Heterogeneous, large, or

deep masses, especially those with a low signal on T1-weighted images

and a higher signal on T2-weighted images, or those with gadolinium

enhancement, should be suspected to be soft-tissue sarcomas. Additional

imaging tests may be indicated, depending on the clinical diagnosis.

Note that any local imaging study will have real and artifactual

changes introduced by the performance of any operative procedure,

including a biopsy; this will make their interpretation difficult.

Therefore, perform all local imaging studies before any operative

intervention.

location of soft-tissue tumors in the extremities but is more valuable

in the pelvis. In many cases, CT scans reveal the proximity of the

tumor to bone, nerve, and vascular structures; they also accurately

indicate fat density. Lipomas usually can be differentiated from other

tumors. CT scans are also important in the staging of malignant

soft-tissue tumors in that the most common site of metastases from

soft-tissue sarcomas is to the lungs. In comparison to plain

radiography, CT has superior resolution in the imaging of metastatic

disease in the lungs. Perform a CT scan of the retroperitoneum in the

evaluation of extremity myxoid liposarcomas because, on occasion,

patients will have concomitant disease in the retroperitoneum and

extremities.

with a soft-tissue mass. The biopsy is a technically simple procedure,

but it requires extensive training and experience. A well-planned and

executed biopsy provides an accurate diagnosis and facilitates

treatment. A poorly performed biopsy, on the other hand, may fail to

provide a diagnosis and, more important, may have a negative impact on

patient survival and treatment options, especially the potential to

preserve a limb (17). For these reasons, if a soft-tissue mass may be malignant, the biopsy should be performed

by the surgeon who will ultimately be responsible for the full care of the patient.

closed (needle or trephine). The method is determined by the experience

and preference of the surgeon and the pathologist, the differential

diagnosis, and the anatomic location of the lesion. Closed procedures

are less invasive, require smaller doses of anesthetic and analgesic

agents, and carry a smaller risk in most instances. There is a lower

risk of tumor contamination, hemorrhage, and infection than with open

biopsies. When the procedures are supervised by the treating surgeon,

they may be done under ultrasound or a CT scan visualization in order

to localize the site of the biopsy better. Needle or trephine biopsies

are usually performed in an outpatient or office setting whereas open

biopsies require a full operating facility; therefore, they are less

costly than open procedures (29).

material obtained for pathologic review. For this reason, it is most

important that the pathologist who reviews the material be trained in

and have experience with needle biopsies. Highly accurate results are

seen with closed technique biopies in large medical centers that have a

large volume of musculoskeletal neoplasms (1).

The accuracy of a closed biopsy is further improved by tumor

homogeneity and the strength of supporting evidence provided by the

surgeon regarding the clinical findings and the results of imaging

studies. Closed biopsies are less reliable for cystic or myxoid tumors

or heterogeneous-appearing neoplasms (29). With

closed biopsy, there may not be enough pathologic material for

additional studies such as cytogenetics or tissue culture, or for

cellular research. Closed biopsies are more prone than open biopsies to

sampling error, especially in heterogeneous tumors. The tissue

architecture,

which is important in determining tumor grade, may be more difficult to ascertain in a closed biopsy than in an open one.

analgesia required, and the greater cost of an open biopsy, it is the

most reliable method for obtaining representative tissue. Open biopsies

may be excisional or incisional. However, because of the technical

difficulty in performing an incisional biopsy in the case of very small

tumors, an open excisional biopsy is indicated for these tumors. In

very small tumors, take a small cuff of surrounding tissue en bloc with the tumor (primary wide excision) because additional surgery may not be necessary, even in cases of malignancy.

must be localized to obtain the best access to the tumor and it also

must be in a position where the site can be excised en bloc with the tumor should it prove to be malignant.

-

Perform the biopsy through a longitudinal

incision. In the operative dissection, do not expose or contaminate

important vascular or neural structures. Do not violate anatomic

compartments other than those containing the tumor. -

Take special care around joints to prevent intraarticular contamination with tumor cells.

-

Biopsies of soft tissue should not involve major tendons (e.g., the patellar tendon) or their insertion.

-

In a biopsy, do not use intramuscular or

intranervous planes, as in more standard orthopaedic approaches.

Instead, use a direct approach with the smallest possible incision

directly through skin, subcutaneous tissue, fascia, and muscle down to

the tumor.

fine-needle aspiration is based on a pathologist’s cytologic

interpretation of single cells aspirated through a 0.6 to 1.0

mm—diameter needle. Fine-needle aspiration is more accurate in

diagnosing homogeneous tumors than inhomogeneous tumors.

-

After preparation of the skin, use the

needle to make serial aspirations of the tumor bed through a single

entry site. This site is agreed on by both the surgeon and the

pathologist; ideally, mark it with any method that will allow future

identification. -

This specimen is prepared immediately by

the cytology technician, and the tissue is fixed according to the

cytologist’s preference. Often, the slides can be evaluated immediately. -

Maintain pressure on the biopsy site so that hematoma formation is minimized.

needle biopsy is a trephine biopsy in which a 14-gauge cannula and

trocar system are used that allow cores (approximately 1.75 mm) of

tissue to be obtained with preservation of the architecture of the

specimen.

-

After preparation of the skin and infiltration with local anesthesia, use a #11 blade to incise the skin 2 to 3 mm.

-

Then place the Tru-cut needle into the

tumor bed. It is helpful to introduce the Tru-cut with the outer

cannula sheath retracted, exposing the inner trocar tip and specimen

notch. -

Sharply advance the outer cannula once

the needle tip is placed within the tumor mass itself, so that an inner

core of tissue is trapped. -

Repeat this procedure until multiple cores are available for pathologic review.

-

Process the specimens with fixation in formalin or in gluteraldehyde.

-

Maintain pressure on the site for several minutes to minimize hematoma formation.

the diagnosis in soft-tissue tumors. Make the incision as small as is

compatible with obtaining an adequate tumor specimen. Except for

regions over the iliac crest or clavicle, longitudinal incisions are

recommended.

-

Proceed sharply through subcutaneous fat,

fascia, and muscle. For intramuscular tumors, a color change in muscle

from red to salmon often heralds the approaching tumor pseudocapsule.

Malignant tumors are usually gray or white. -

Sample diagnostic tissue at the periphery

of the tumor, which typically is the most viable region. A biopsy of

necrotic appearing tissue is usually not of benefit. -

Perform frozen sections in all cases, if

possible, for confirmation of the presence of tissue from which the

pathologist may make a diagnosis. This is true even if definitive

surgery is not planned at the same time. -

Meticulous hemostasis is essential so tumor spread by hematoma is prevented.

-

Drains may be used, but they should be

placed close to and in line with the incision to allow the future

excision of the drain site along with the biopsy site. An outside-in

technique for introduction of the drain, when the drain site is made

with a scalpel and the drain is placed retrograde into the wound, is

preferable to the use of a trocar from the deeper wound through the

skin. -

As with all surgical procedures, minimize

postoperative limb swelling, edema, and bleeding through the use of

sterile compressive dressings. Limb immobilization and elevation may

also be required.

specific type of procedure performed depend on many factors, including

the diagnosis, the local and distant extent of disease, the tumor

location, the functional consequences of resection, and the patient’s

symptoms. An estimation of the growth pattern and malignant potential

of the tumor will ultimately dictate treatment. Some benign tumors

(e.g., lipomas) grow slowly in a centrifugal fashion and are bounded by

surrounding anatomic structures such as fascia, bone, nerve, or

vessels. A compressed area of fibrous adventitial and vascular

structures forms a true capsule surrounding these neoplasms. In

contrast, other benign tumors, such as intramuscular hemangiomas or

desmoid tumors, lack a true capsule and often have permeative and

infiltrative borders. Even malignant soft-tissue tumors, at least early

on, respect anatomic borders but, instead of a true capsule, are

surrounded by a “pseudocapsule” or reactive zone (7).

This zone and the area surrounding it contain microscopic extensions or

satellites of malignant tumor. An understanding of the growth

characteristics is important in the selection of the most effective

operative procedure for obtaining local control.

-

An intralesional

resection is performed within the reactive zone of the tumor and

includes debulking procedures. This form of resection is likely to

leave both macroscopic and microscopic residual disease and to be

associated with a high incidence of local relapse. -

A marginal

resection is performed through the tissue plane of the capsule or

reactive zone. This procedure is indicated for many benign tumors, but

it is associated with an unacceptable risk of local recurrence in the

case of malignant tumors because of residual microscopic peripheral

satellite disease. For this reason, in the treatment of sarcomas, an

effective adjuvant, most often radiation therapy, is administered in

combination with a marginal operative resection for obtaining local

control. -

A wide

resection, performed in normal tissue peripheral to the reactive zone,

is preferred for a soft-tissue sarcoma. With modern imaging for

accurate determination of the tumor extent, this operative procedure is

associated with a low incidence of local relapse and is recommended for

most infiltrative benign and malignant tumors. -

A radical

resection is one in which the entire anatomic compartment of tumor

origin is removed. This procedure carries little, if any, advantage

over wide resection in minimizing the prevalence of local recurrence

and is now only rarely performed.

may also be defined as marginal, wide, or radical according to the

above-mentioned definitions. The indications for amputation are sepsis,

extensive contamination of tumor from hemorrhage, a poorly performed

biopsy, or extensive tumor involvement of vital neurovascular

structures. Amputation may also be considered when the functional

results after an ablative procedure would be superior to those

following resection and adjuvant therapy. Additional indications may be

the presence of multifocal disease, intractable pain, or local relapse.

|

|

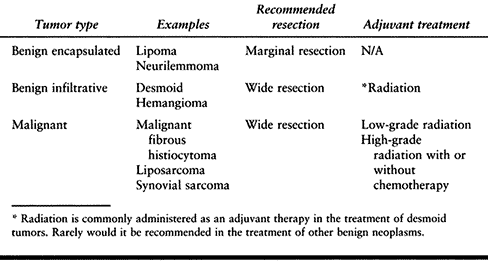

Table 129.1. Operative Procedures in the Treatment of Soft-Tissue Neoplasms

|

the functional consequences of resection determine the operative

strategy. Asymptomatic benign tumors may be treated nonoperatively in

an area where function after surgery is likely to be compromised.

Benign tumors in easily accessible sites are often removed even in the

absence of symptoms. For sarcomas located in the distal leg or foot,

amputation may be preferable for tumor control, given the relatively

good function and oncologic results after distal lower extremity

amputations. A malignant tumor adjacent to a major nerve or artery may

dictate that a marginal resection, in addition to some form of adjuvant

therapy, be administered.

influences the surgeon’s decision as to what procedure to perform. In

patients with malignant disease, it is important to determine the local

and distant extent (metastases) of the tumor. Soft-tissue sarcomas most

commonly metastasize to the lungs, and chest radiography and CT are

indicated as a part of the initial evaluation. Metastases to lymph

nodes and bone are unusual, and the additional value of technetium bone

scanning, gallium scanning, or positron-emission tomography (PET)

scanning is not clear. Adults with metastatic soft-tissue sarcomas at

the time of diagnosis, or with severe comorbid medical conditions, have

a very poor prognosis, and surgery may not be indicated except for

palliation. Similarly, in some benign tumors, such as plexiform

neurofibromas or extensive intramuscular hemangiomas, the tumor may be

so extensive locally that resection would be associated with severe

functional disability. In such cases, it may be in the patient’s best

interest not to attempt to resect all disease.

Most are small (smaller than 5 cm) and are presumed, before operative

resection, to be benign neoplasms. Therefore, most subcutaneous

sarcomas are referred to surgical oncologists after excision. On

reexcision of the tumor bed, focal residual sarcoma has been noted in

more than one half of the patients treated (12,20).

For this reason, surgical reexcision of the operative field is

recommended in the treatment of patients with subcutaneous sarcomas.

With such treatment, excellent rates of local control can be obtained (10).

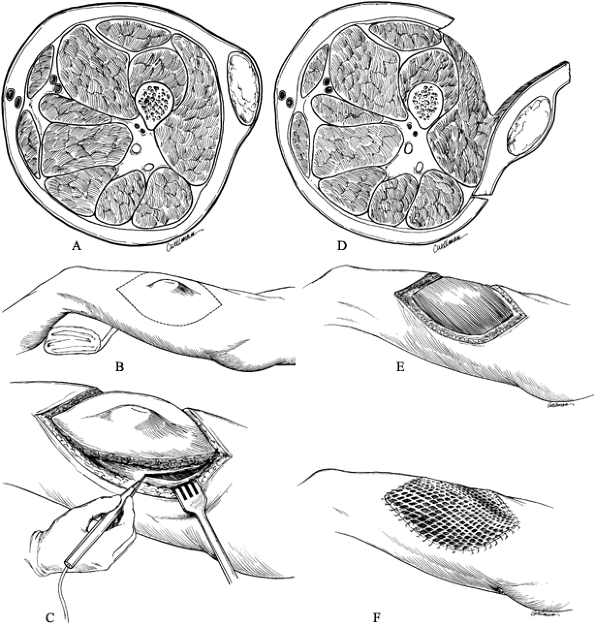

normal cuff of skin and subcutaneous fat in continuity with fascia and

muscle. Because there is no anatomic barrier to the spread of a

subcutaneous sarcoma, the surgeon must determine, by palpation and

careful review of imaging studies, the extent of a resection that will

be necessary to encompass the entire previous operative field while

remaining in normal tissue. Fortunately, in a subcutaneous location,

major neurovascular structures are rarely involved.

|

|

Figure 129.2. Operative technique for a wide excision of a subcutaneous sarcoma in the midlateral aspect of the thigh. A:

Cross section of the thigh; the lesion is completely contained within the subcutaneous tissue and does not involve the underlying fascia. B: The planned margin of resection of the previously biopsied tumor is indicated by the dotted line. C: A sharp dissection is performed through the subcutaneous tissue away from the mass, with use of the underlying fascia as the deep margin. D: The wide margin, including the deep fascia, seen in cross section. E: The muscle bed after resection. F: The defect is covered with a split-thickness skin graft. |

-

Dissect directly through skin, subcutaneous tissue, and fascia.

-

Take a small amount of superficial muscle

deep to the fascia in continuity with the resected specimen. In most

instances, a split-thickness skin graft is required to close the defect

over the remaining muscle. Occasionally, in certain anatomic locations

such as in the inguinal region or in obese patients, elliptical

incision may be made allowing resection of the tumor and primary

closure of the wound. -

Take care not to compromise the amount of

soft-tissue resected in order to obtain primary closure. Infrequently,

a rotational or free flap is required for closure over bony surfaces

such as the tibia.

large (larger than 5 cm) and are suspected to be malignant before

operative resection. The most common site of a soft-tissue sarcoma is

the thigh, and the tumor may be located in the anterior, posterior, or

adductor compartment. In some cases, the tumor may be located in more

than one anatomic compartment, or it may be extracompartmental

(popliteal fossa). Often, the femur, superficial femoral artery and

vein, femoral nerve, or sciatic nerve may be adjacent to the tumor

mass. It is unusual for a soft-tissue sarcoma to invade neurovascular

structures directly.

marginal resection so that the occurrence of local relapse is

minimized. However, if the tumor is immediately adjacent to bone, the

sciatic nerve, or in some cases, the superficial femoral artery, a

marginal resection is all that can be accomplished without severe

compromise of limb function. In these cases, adjuvant therapy, most

commonly in the form of radiation therapy, either external beam or

brachytherapy, can be administered preoperatively or postoperatively to minimize the chance of local recurrence.

-

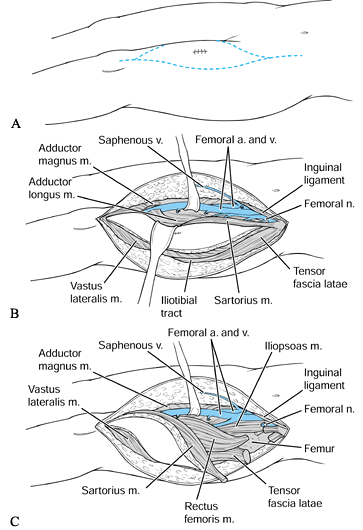

Make the skin incision longitudinally over the extent of the tumor, ellipsing any previous biopsy site (Fig. 129.3).

Dissect sharply through the subcutaneous tissue. Bevel the dissection

outward at a 45° angle to the skin to increase the width of the

resection further.![]() Figure 129.3. Wide resection of a deep sarcoma of the thigh. A:

Figure 129.3. Wide resection of a deep sarcoma of the thigh. A:

Skin incision from the anterior superior iliac spine to the superior

pole of the patella, including the site of elliptically excised biopsy

specimen, for a deep intracompartmental tumor of the anterior thigh. B: Creation of skin flaps and dissection of superficial femoral vessels. C: Transection of muscle circumferentially around the tumor mass. -

Based on palpation and imaging studies,

make a circumferential fascial incision, often in the form of an

ellipse, 2 to 3 cm away from the tumor mass. It is important that skin,

subcutaneous fat, and fascia remain attached to the underlying tumor

mass. -

At this time, locate the superficial

femoral artery and vein proximally and dissect them from proximal to

distal. Ligate multiple branches in the region of the tumor. In cases

of anterior thigh sarcomas, the femoral nerve must often be sacrificed

proximally. Once the artery and vein have been freed from the

underlying soft tissue, retract them medially and proceed with the

resection. -

Transect muscle fibers on the periphery

of the tumor for preservation of a cuff of normal tissue around the

tumor pseudocapsule. Make every effort to avoid visualizing or

penetrating the tumor pseudocapsule. -

If the tumor is immediately adjacent to

the femur, it may be necessary to perform a subperiosteal dissection

and include the periosteum as a deep margin. Be aware, however, that

such subperiosteal dissection in the face of adjuvant radiation therapy

may predispose a patient to a pathologic fracture of the femur due to

the radiation therapy (15). -

Then sever surrounding muscle

attachments, and remove the tumor from the thigh. Additional effort to

remove entire muscles from origin to insertion (a radical resection) is

not necessary in the treatment of most soft-tissue sarcomas. -

Irrigate the wound and close over suction drains. Leave the drains in place for a prolonged period to evacuate any dead space.

to allow for optimal wound healing and to minimize seroma formation. In

some cases, a rotational free flap may be necessary to provide

vascularized tissue deep to the skin and to assist in wound healing.

described earlier in that no effort is made to preserve a normal cuff

of tissue about the tumor. In these cases, dissection proceeds through

the capsule of the tumor itself without removal of additional soft

tissue. This procedure is most commonly carried out for deep

intramuscular lipomas. It is not recommended for the treatment of

malignant disease.

-

Make a longitudinal incision, slightly

longer than the underlying tumor mass, directly over the most prominent

portion of the tumor. The skin, subcutaneous tissue, and, in some

cases, muscle must be longitudinally divided and bluntly dissected to

reveal the underlying capsule of the tumor. -

Then deliver the tumor mass from the

wound, again working in the adventitial layer covering the tumor,

dissecting circumferentially around the tumor mass. Then remove the

tumor. -

Irrigate the wounds and close over drains if necessary.

“non-epithelial extra-skeletal tissue of the body exclusive of the

reticuloendothelial system, glia, and supporting tissue of various

mesenchymal organ” (9). Benign soft-tissue

neoplasms are believed to be at least 100 times more common than their

malignant counterparts, soft-tissue sarcomas. Soft-tissue sarcomas may

arise in any part of the body but are most common in the extremities,

specifically the thigh and buttock. Common benign deep soft-tissue

tumors include intramuscular lipomas, extraabdominal fibromatosis

(desmoid tumors) hemangiomas, and benign nerve sheath tumors.

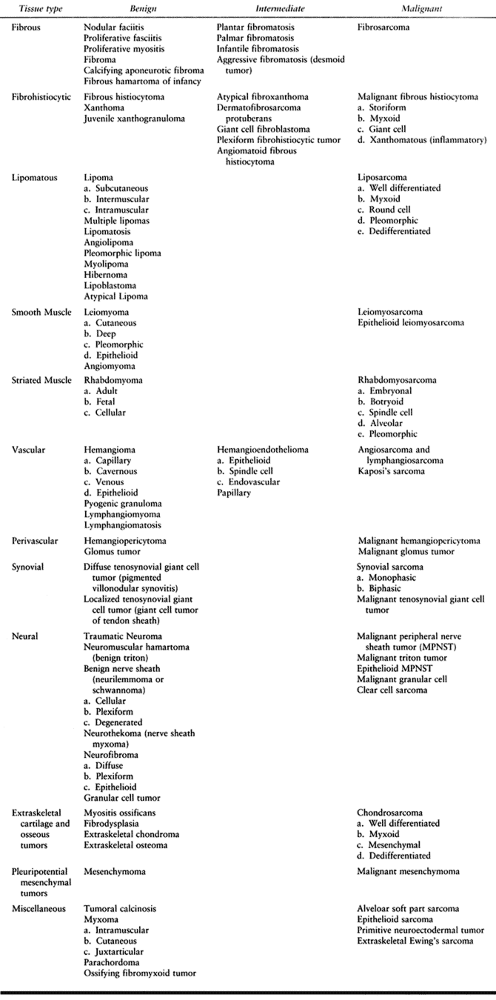

believed to arise from normal cells of a similar histologic appearance,

the current histologic classification of soft-tissue tumors is based on

the apparent differentiation of the tumor cell. Most tumors arise from

an undifferentiated precursor cell and acquire phenotypic traits of

various normal cells during neoplastic transformation. It is this

appearance by which the tumors are classified rather than by the tissue

of origin. The tumors are classified as benign, intermediate, or

malignant based on their perceived capability of metastasis. Malignant

tumors are subcategorized as low grade or high grade based on their

histologic characteristics including tumor necrosis, cellular

anaplasia, and the number of mitotic figures. Patients with high-grade

tumors are at an increased risk for developing metastatic disease

compared with those with low-grade tumors.

This table is based largely on the classification of soft-tissue tumors

by the World Health Organization, with subsequent modification as

described by Enzinger and Weiss. Again, this classification of tumors

does not imply that the histologic appearance of the tumor is related

to the tissue of origin. In addition, one must be careful not to assume

that malignant soft-tissue tumors of one histologic type are the result

of malignant degeneration of a benign neoplasm. Malignant degeneration

of an underlying benign soft-tissue neoplasm is very rare.

|

|

Table 129.2. Histologic Classification of Soft-Tissue Tumors11

|

resembles fibrous tissue are common and may be reactive (nodular

fasciitis), benign (fibroma of tendon sheath), infiltrative (desmoid

tumor), or malignant (fibrosarcoma). Fibrous neoplasms of infancy and

childhood should be considered separately because of their unique and

often self-limiting behavior.

fibroblasts often mistaken for a malignant soft tissue tumor because of

its rapid onset of growth, mitotic activity, and cellularity. It is

most likely a self-limiting reactive process rather than a true

neoplasm. Most patients present with a rapidly growing mass with

associated tenderness. It is often located in the upper extremities,

especially in the volar aspect of the forearm. In infants and children,

it may be found in the head and neck region. It is usually small

(smaller than 5 centimeters). It may be subcutaneous, intramuscular, or

fascial based. It is usually treated by marginal excision and has a low

recurrence rate (4). Spontaneous regression has been observed.

Dupuytren’s contracture and is the most common type of fibromatosis.

Its etiology is unclear. It is seen most commonly in people older than

65 years of age. It may be associated with other forms of fibromatosis

including plantar fibromatosis and penile fibromatosis (Peyronie’s

disease). It is also noted to be of increased incidence in patients

with epilepsy and diabetes. It has also been known to be associated

with chronic alcoholism and liver cirrhosis.

firm nodule is palpable in the palmar aspect of the hand affecting the

ulnar aspect of the hand. It may be associated with joint contracture.

A single small nodule or an ill-defined conglomerate of several nodules

is found on examination. Pathology consists of spindle-shaped

fibroblasts and variable amounts of dense collagen. Treatment may

include nonoperative therapy including physical therapy and topical

treatment, but rarely do these measures have a significant effect on

the disease. Operative resection, however, remains the treatment of

choice in the patient with impairment secondary to flexion contractures

of the digits. Fasciectomy is usually recommended as the treatment of

choice (23). Local recurrence may result in recurrent contracture.

identified by nodular fibrous proliferation arising with the plantar

aponeurosis. Unlike disease in the hand, it is usually not associated

with contractures of the digits. Usually, a single subcutaneous

thickening or nodule that adheres to skin and is located in the middle

or medial portion of the foot is found on examination. It may be

painful and may be bilateral. The lesion is more common in men than

women. It occurs in younger individuals than palmar fi- bromatosis.

Pathologic findings are identical to palmar fibromatosis. Treatment is

directed at the patient’s symptoms, and nonoperative therapy consists

of shoe pads and modified shoe wear. Radical fasciectomy is considered

for patients with intractable pain but is associated with local

recurrence in a number of cases (6).

neoplasms. It has the potential to attain a large size, often recurs

despite operative resection, and is infiltrative in nature. It may be

associated with colonic polyposis (Gardner’s syndrome). Clinical

findings are usually a soft-tissue mass in the young adult. It is

common about the shoulder, flank, and the muscles of the thigh. It may

be multifocal within an extremity. Histologically, fibromatosis is

benign in appearance with spindle-shaped fibroblasts and dense

collagen. Imaging studies reveal that the tumor is typically of low

signal on both T1- and T2-weighted images because of the large collagen

content. Operative resection is considered for tumors in expendable

locations (3).

However, despite complete surgical resection, it is associated with

recurrence in a number of cases. Adjuvant treatment in the form of

radiation therapy is often considered for these individuals. Medical

treatment in the form of estrogen blockade or chemotherapy may be

considered in selected circumstances.

cells resemble fibroblasts but with significant cellular atypia,

frequent mitoses, and increased cellularity compared with its benign

counterparts. Before the subclassification of malignant fibrous

histiocytoma, fibrosarcomas were the most common soft-tissue

malignancies. Fibrosarcomas are often low grade. The recommended

treatment is wide resection or marginal resection combined with

adjuvant radiation therapy.

storiform or cartwheel-type growth pattern. The actual histogenesis of

the tumor may not be from a histiocyte but more closely related to the

fibroblast. This tumor is also known as an adult spindle cell sarcoma.

These neoplasms may be low grade or high grade based on their

cellularity, atypia, and the presence or absence of mitotic figures and

necrosis. They are commonly located in the subcutaneous tissue or the

deep soft tissues of the thigh. Like other soft-tissue sarcomas, they

are best treated with wide resection. Marginal resection can be

combined with adjuvant radiation therapy. Patients with large,

high-grade soft tissue sarcomas may, in addition, benefit from adjuvant

chemotherapy (26).

virtually anywhere in the body. The tumor is usually a soft, mobile,

and asymptomatic mass with a very large range of sizes noted. The

magnetic resonance images of a lipoma show signal characteristics

similar to surrounding fat on all sequences. It is the one tumor that

can usually be diagnosed by MRI. Asymptomatic lesions do not require

treatment. Malignant transformation is rare. Symptomatic tumors are

usually treated with local excision. Local recurrence is rare.

soft-tissue tumor seen in the extremities. It is also very common in

the retroperitoneum. Liposarcomas may be low grade or high grade. The

characteristic cell is the lipoblast, which consists of a cell

containing large amounts of clear cytoplasm but with several septated

vacuoles that secondarily indent the nucleus. This is different from

the signet ring cell, a cell with a large clear cytoplasm and a thinned

eccentric nucleus at one pole. Signet ring cells can be seen in both

benign and malignant lipomatous soft tissue tumors. The lipoblast is

characteristic of a malignant tumor. Higher grade liposarcomas may be

difficult to differentiate from other soft-tissue sarcomas such as

malignant fibrous histiocytoma because of the dense cellularity

obscuring those cells that resemble fat. It should be noted that

liposarcomas do not have an appearance similar to lipomas on MRI, that

is, they tend to be of low signal on T1-weighted images and of bright

signal on T2-weighted images. The management of liposarcoma is

identical to other soft-tissue sarcomas, that is, wide resection when

possible or marginal resection with adjuvant radiation therapy. Unlike

other soft-tissue sarcomas, however, liposarcomas (especially the

myxoid type) of the extremity may be associated with disease in other,

nonpulmonary sites (e.g., retroperitoneum) (21).

seen in the extremities. Benign neoplasms may be managed with marginal

resection. Malignant soft-tissue sarcomas require wide resection or

marginal resection and adjuvant radiation therapy.

rhabdomyoma is exceptionally unusual and of variable presentation. The

diagnosis is usually made on the basis of an open biopsy.

Rhabdomyosarcoma, although unusual, is the most common soft-tissue

malignancy of children. When it is located in an extremity, it is often

of the alveolar histologic type. The characteristic tumor cell of a

rhabdomyosarcoma is the rhabdoid cell, which is a large, irregularly

shaped cell with an eccentric nucleus and eosinophillic cytoplasm.

These high-grade tumors are often associated

with metastatic disease at the time of presentation and are treated with systemic chemotherapy (5).

The role of operative intervention is unclear and controversial.

Radiation therapy may be considered. These tumors may actually be more

closely related to soft-tissue Ewing’s or soft-tissue primitive

neuroectodermal tumor.

vessels. Some actually represent vascular malformations rather than

true neoplasms. They are often seen in infants and may spontaneously

regress. They may be localized or multifocal, in which case they are

known as angiomatosis (22). The majority of

hemangiomas are superficial lesions with a predilection for the head

and neck but may also occur internally. Tumors may be responsive to

circulating hormones, and changes in size may be seen during pregnancy.

Based on the histologic appearance, they are subclassified as capillary

hemangiomas, which are often seen in children. Cavernous hemangiomas

are large with thin-walled veins. Hemangiomas may be seen in

conjunction with dyschondroplasia, also known as Maffucci’s syndrome.

When the tumor is located in a subcutaneous or dermal location, there

often are characteristic color changes to the skin. There is no such

skin change found with deeper situated tumors. Radiographs may

demonstrate phleboliths within the lesion. Vascular studies and

ultrasound may show vascular flow but may be difficult to distinguish

from other vascular neoplasms.

diagnosis is known, is based on symptoms. Again, many grow slowly if at

all. This is especially true in children, in whom lesions are often

known to regress spontaneously. Localized disease may be marginally

resected, with an approximate 20% local recurrence rate. More

difficulties are encountered with the extensive hemangiomas and

multifocal hemangiomas. Angiographic embolization has been used to

treat many afflicted individuals with variable success. Radiation

therapy has been considered in the past but should be used with great

caution in young people.

vessels are rare. Significant is the association of angiosarcoma with

chronic lymphedema, for example, in patients following mastectomy and

lymph node resection. Operative wide resection is the treatment of

choice, and multifocal disease is commonly encountered.

juxtaarticular or intraarticular locations. Intraarticular disease is

known as pigmented villonodular synovitis and, again, may be localized

or diffuse (27). Tenosynovial giant cell tumor

affecting the tendon sheath is known as giant cell tumor of the tendon

sheath. These tumors are believed to be benign neoplasms that may

actually be reactive in etiology. Localized disease is usually treated

with marginal resection. Diffuse disease, especially intraarticular

disease in a large joint, such as the knee, may require synovectomy,

and intraarticular or external beam radiation therapy.

sarcoma in adults and the second most frequently seen soft-tissue

sarcoma in children. It is typically not located within a joint but

within the structures about a joint. Many are located in the hand or

foot. These tumors may be monophasic or so-called biphasic, consisting

of plump synovial cells arranged in a glandular pattern with other

fibroblastic areas around it. Radiographs of these lesions may reveal

mineralization in the form of calcification. Like other soft-tissue

sarcomas, MRI studies usually show predominantly low signal on

T1-weighted images and bright signal on T2-weighted images. These

lesions usually enhance with gadolinium infusion.

wide resection or marginal resection and radiation therapy. Some

synovial sarcomas may respond well to systemic chemotherapy (28).

locations and may be solitary or part of a neurofibromatosis or von

Recklinghausen disease (13). Often, this

disease is noted as an inherited dominant trait of variable

penetration. It may be associated with scoliosis, congenital

pseudarthrosis of the tibia or clavicle, and gigantism. Neurofibromas

are often asymptomatic. People with von Recklinghausen’s disease may

develop malignant nerve sheath tumors as well. Sarcomatous degeneration

should be suspected in patients with very large or rapidly growing

tumors.

localized, neurofibromas are often extensive and infiltrative in nature

around the nerve of origin. For this reason, if it is decided to remove

these tumors, it is often necessary to resect the underlying nerve.

Operative resection, however, is only indicated for symptomatic lesions

or for those suspected of sarcomatous degeneration.

nerve sheath itself. It is often a fusiform soft-tissue mass tapered at

either end by the axons resuming their normal position within the nerve

proximal and distal to the lesion. The MRI scan often shows that this

tumor is of very bright signal on T2-weighted images and is usually

homogeneous. Physical findings often reveal Tinel’s sign or a radiating

sensation with direct percussion. Marginal resections are associated

with a low incidence of recurrence. Pathology reveals a biphasic

appearance with compact (Antoni A) or densely cellular areas

alternating with areas with relatively few cells (Antoni B). Small

clusters of palisading cells around a central eosinophilic area are

known as Verocay bodies. Operative excision is often carried out as a

form of diagnostic biopsy in which the nerve sheath itself is split

longitudinally in order to remove the lesion without harming the

surrounding axons. It is usually encapsulated and freed relatively

easily from the underlying nerve.

behavior, however, is not unlike other high-grade soft-tissue sarcomas (14). Operative treatment is preferably wide resection or marginal resection with adjuvant treatment

soft-tissue tumors in an effort to predict the prognosis and evaluate

the effect of therapeutic intervention by stratifying similar tumors

according to various prognostic factors. Commonly used factors are

tumor grade, size, compartmentalization of the tumor, and the presence

or absence of metastases.

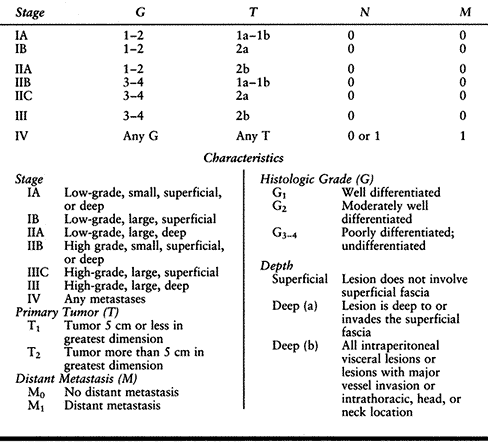

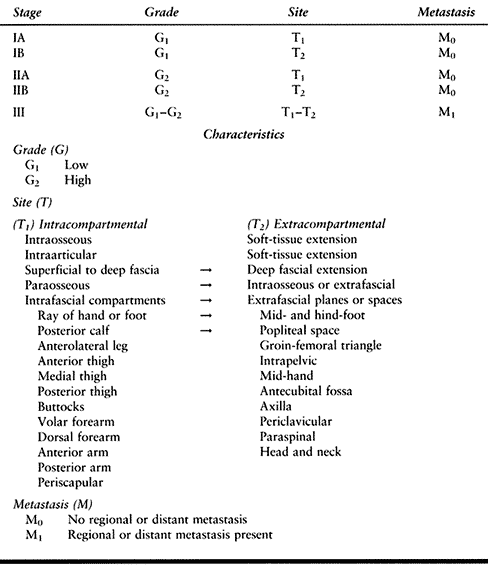

systems that are used at present were developed by the American Joint

Committee on Cancer (AJCC; Table 129.3) (2) and by Enneking (Table 129.4) (8).

In both systems, the variables used in the assignment of an appropriate

stage include tumor grade, location, and the relative extent of the

tumor, as well as the presence or absence of metastases.

|

|

Table 129.3. American Joint Committee Staging Protocol for Sarcoma of Soft Tissue (2)

|

|

|

Table 129.4. Enneking System for Staging of Soft-Tissue Sarcomas

|

very poor prognostic factor. This is true if metastases occur either to

the lungs or to lymph nodes. The differences between the systems is

that, first, the AJCC system is based on a grading system containing

four variables, whereas the Enneking system considers only high and low

grades. Second, the AJCC system uses tumor size as an important

prognostic variable as opposed to compartmental location as described

by Enneking. Third, the AJCC system considers tumor depth to be an

important prognostic factor.

and clinical observations, and they serve to guide therapeutic

strategies. However, these systems are based on variables that are

crude and of limited usefulness. New discoveries in the fields of

molecular and cellular biology are being made and will be correlated

with the clinical course and outcome. These findings almost certainly

will change the manner in which tumors are classified and staged, and

will predict more accurately the behavior of a given tumor in a

particular patient. Operative treatment, chemotherapy, and radiation

therapy can then be used in a rational and effective manner to improve

the functional and oncologic outcome (19).

tumors are the same as those encountered for all orthopaedic surgery,

as discussed in Chapter 5 and Chapter 8.

The two most significant complications of the management of soft-tissue

tumors of the extremities are improper performance of a biopsy, which

leads to either misdiagnosis or compromise

of

the definitive method for surgical treatment, or recurrence after

resection of an aggressive benign tumor or malignant tumor. Small

benign-appearing tumors in the distal portions of the extremities are

commonly removed by general orthopaedic and other surgeons by

excisional biopsy with marginal resection. When histology reveals a

malignant tumor, it is prudent to have the next stage of treatment

management performed by an experienced oncology team consisting of a

surgeon, medical oncologist, and radiation therapy specialist. In the

case of lesions in which a malignant tumor is an obvious part of the

prebiopsy differential diagnosis, biopsy should be performed only by a

surgeon experienced in the treatment of malignant tumors who is

prepared to carry out definitive treatment in conjunction with an

oncology team. This approach will minimize the risk of local recurrence

and enhance the long-term survival of patients with these troublesome

tumors. In performing biopsy and subsequent resection of these tumors,

the principles discussed in this chapter must be meticulously followed.

scheme: *, classic article; #, review article; !, basic research

article; and +, clinical results/outcome study.

M, Rydholm A, Persson BM. Aspiration Cytology and Soft-Tissue Tumors.

The 10-year Experience at an Orthopaedic Oncology Center. Acta Orthop Scand 1985;56:407.

M, Zajars G, Pollack A, et al. Desmoid Tumor: Prognostic Factors and

Outcome after Surgery, Radiation Therapy, or Combined Surgery and

Radiation Therapy. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:158.

CP, Peabody TD, Mundt AS, et al. Oncologic Outcomes of Operative

Treatment of Subcutaneous Soft-Tissue Sarcomas of the Extremities. J Bone Joint Surg 1991;79A:888.

CP, Peabody TD, Simon MA. Mini-Symposium: Soft Tissue Tumors of the

Musculoskeletal System (i). Classification, Clinical Features,

Preoperative Assessment, and Staging of Soft Tissue Tumors, Current Orthopaedics 1997;11:75

R, Shiu M, Senie R, Woodruff J. Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath

Tumors of the Buttock and Lower Extremity. A Study of 43 Cases. Cancer 1990;66:1253.

O. A Consecutive 7-Year Series of 1,331 Benign Soft-Tissue Tumors.

Clinicopathologic Data. Comparison with Sarcomas. Acta Orthop Scand 1981;52:287.

JJ, Neibauer JJ, Brown RL, et al. Treatment of Dupuytren’s Contracture.

Long-term Results after Fasciotomy and Fascial Excision. J Bone Joint Surg 1976;58A:380.

S, Baldini E, Demetri G, et al. Synovial Sarcoma: Prognostic

Significance of Tumor Size, Margin of Resection and Mitotic Activity

for Survival. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:1201.

MC, Biermann JS, Montag A, Simon MA. Diagnostic Accuracy and

Charge-Savings of Outpatient Core Needle Biopsy Compared with Open

Biopsy of Musculoskeletal Tumors. J Bone Joint Surg 1996;78A:644.