AMPUTATIONS OF THE HAND

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Rehabilitation, Loyola University

Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, Maywood, Illinois, 60153.

patient and the surgeon. Nonetheless, a carefully planned and

skillfully executed surgical procedure is essential for early

restoration of pain-free, useful hand function. The ultimate goal of

surgery is the restoration of a hand of acceptable appearance, capable

of the highest degree of function consistent with its remaining

musculoskeletal elements (1,27).

prompt wound healing and joint mobility in digits of maximal length.

The surgeon must take care to preserve sensibility in retained elements

and to prevent formation of painful neuromas.

precision prehension, preservation or restoration of the thumb is of

paramount importance. When the radial fingers are compromised,

precision prehension is impaired, while loss of the ulnar digits

reduces effective power grip (12). Preservation

of length and sensibility is vital to radial digits, whereas

preservation of joint mobility is more important to ulnar digits.

elective, by the mechanism of injury or etiology, or by the anatomic

region of the hand removed. Secondary revision of initially emergent

amputations may be elected to address issues of appearance, function,

or pain.

amputation of portions of the hand. The management of acute traumatic

amputation requires considerable judgment. The surgeon must often

decide which parts should be

retained

by revascularization or replantation, which should be managed with

direct wound closure, and which should be managed primarily by more

proximal surgical amputation.

the likelihood of success with different treatment strategies. Sharp

injuries preserve normal tissues in the proximal part and have a narrow

zone of injury. Distal tissues that may be amenable to reattachment or

revascularization are more likely to be preserved. Crush injuries often

result in a wide zone of injury. Though the skin sleeve may have been

preserved, the profound crushing of underlying bone, joint, and flexor

and extensor tendons may preclude reestablishment of a supple, mobile

digit. Avulsion injuries may result in substantial injury to

neurovascular and tendinous structures proximal to the level of skin

loss or disruption. Examination of amputated parts may aid in

understanding the extent of injury to the residual parts of the hand or

fingers.

easiest, initially, to preserve all viable tissue. Otherwise useless

digits may be converted to fillet flaps for soft-tissue coverage or to

supply digital nerve and bone for graft to be used in other digits.

Although this approach is by design conservative, it will prove

counterproductive if the decision to delete functionless digits is

repeatedly postponed. Retained stiff, insensate, or unstable digits

will compromise the rehabilitation of the remaining, less severely

affected portions of the hand. Also, the original decision to delete

the irreparably compromised digit may be questioned and additional

futile surgeries performed in an attempt to avoid amputation. Early,

appropriate decision making is often difficult: Less experienced

surgeons should seek prompt consultation to establish realistic

expectations for both themselves and their patients.

microvascular or macrovascular disease or a combination of the two.

Microvascular disease, seen commonly in conditions such as scleroderma

and diabetes mellitus, may result in digital ischemia. Irreversible

digital ischemia may also result from macrovascular injury to the

brachial artery after cardiac catheterization in the presence of

systemic atherosclerotic macrovascular and microvascular disease.

amputation. The aim may be either to eliminate a refractory focus of

infection, usually osteomyelitis, or to remove a part whose function

has been irreparably compromised by infection. A painful, swollen

finger rendered immobile after flexor sheath infection may occasionally

be so impaired that the surgeon and patient elect digital amputation.

The histologic character of the tumor and its anatomic location should

be the primary determinants of the level of amputation. The desire to

preserve functional capability must be subservient to the need for

appropriate tumor wound margins (see Chapter 74). Amputation may be confined to a single digit, a ray, or a more major segment of the hand—radial, central, or ulnar.

improved functionally or aesthetically by the amputation of rudimentary

digits. Small, floppy nubbins may be excised when they are insufficient

for reconstruction. When macrodactyly distorts hand form and function,

resection of one or two rays may be indicated. In cases of polydactyly,

amputation of redundant elements must be carefully integrated with

reconstruction of the remaining digits.

Frostbite injury characteristically affects the distal portions of the

fingers. The thumb is less often involved since it is shorter than the

fingers and is often protected by the fingers flexed around it against

the palm. Patients who have experienced severe cold exposure may

experience the effects of ischemia involving all the fingers, both

thumbs, and all toes of both feet, profoundly limiting secondary

reconstruction alternatives. The extent of remaining viable tissue is

often uncertain for a number of days. In selected severe injury, bone

scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may reveal preservation of

osseous circulation in spite of overlying skin necrosis.

structures, skin, and extensor mechanism without necessitating

amputation. Electrical injury, by contrast, may have a more profound

effect on deep tissues than on the skin. Early resection of the finger

or ray that transmitted the electrical impulse is often necessary.

Residual functional impairment after electrical injury may lead to

secondary amputation.

reconstructive surgical procedures in favor of prosthetic management.

When a hand is painful, deformed, and without function, amputation may

be the most effective reconstructive procedure (2).

-

Design skin incisions and skin flaps to provide sensate skin over the palmar surface of the residual digit.

-

Isolate each digital nerve in the

involved digit. Apply modest traction to the nerve, and sharply divide

the nerve, allowing it to retract proximally into soft tissue. -

Identify transected tendons and draw them

distally into the wound. Sharply divide each tendon and allow it to

retract proximally. Do not sew flexor or extensor

P.1453

tendons

to one another over the end of the amputated digit. To do so will

restrict motion in the residual portion of the digit and severely

compromise tendon excursion and motion in adjacent fingers (see the

discussion of the “quadriga” effect in the section below, Pitfalls and Complications). -

Ligate bleeding vessels at wound margins.

-

Traumatic amputations that create oblique

or jagged distal surfaces may result in a painful digit. Trim bone ends

transversely and free them of palmar prominences.

strength, and length that allow the thumb to carry out its unique range

of activity (13). Motion, sensibility, and appearance are important but less vital attributes of normal thumb function.

role in prehension, preserving thumb length is a priority in the

treatment of traumatic thumb injuries. A well-motored stiff thumb with

basilar mobility and normal length is effective in most functions of

the hand.

the distal phalanx, local flap closure may be required. With

disproportionate palmar skin loss, the Moberg palmar advancement flap

allows preservation of thumb length with advancement of sensate skin

distally (5). The radial nerve–innervated

cross-finger flap from the dorsum of the index finger also brings

sensate skin to the distal phalanx (see Chapter 38).

portion of the proximal phalanx or beyond, satisfactory function may be

achieved if maximal length is preserved with local advancement flaps.

severely compromises prehension. Although thumb length may be

sufficient for buttressing of objects in the palm in power grip, it is

insufficient to reach the tips of adjacent fingers in precision

prehensile activities. Secondary surgical reconstruction is usually

advantageous when amputation occurs proximal to the middle of the

proximal phalanx of the thumb. In such situations, the sacrifice of a

few millimeters of skeletal length to allow direct soft-tissue closure

over bone is usually preferable to extensive primary soft-tissue flap

procedures. Once healing of the amputation has been achieved,

reconstruction will be required to restore at least a portion of the

lost thumb length.

of a thumb that has sustained amputation injury include phalangization,

distraction lengthening, and pollicization, as well as toe-to-hand and

wraparound flap microvascular transfers (see Chapter 34, Chapter 35 and Chapter 36 and Chapter 69).

other digits that could achieve pulp-to-pulp contact with the thumb, it

makes little sense to lengthen the thumb beyond the arc of the

remaining fingers. Phalangization restores primitive prehension to the

hand. To be successful, it requires supple dorsal skin, normal thenar

musculature, and a mobile carpometacarpal joint (24).

-

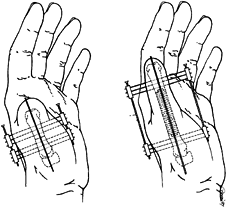

Make a Z-shaped

incision that provides generous web-space exposure and allows flap

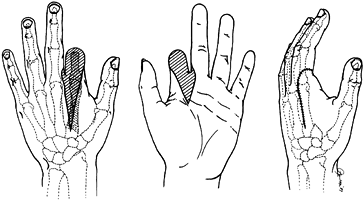

transposition, which shifts the web-space skin margin proximally (Fig. 46.1). Define the adductor pollicis and first dorsal interosseous muscles, and incise and release their investing fascia. Figure 46.1. Phalangization procedure. A: Resection of the index metacarpal is achieved through Z-plasty flap elevation. B: Z-plasty flap transposition increases the exposed prehensile surface of the thumb.

Figure 46.1. Phalangization procedure. A: Resection of the index metacarpal is achieved through Z-plasty flap elevation. B: Z-plasty flap transposition increases the exposed prehensile surface of the thumb. -

Resect the index metacarpal, taking care

to preserve the proximal attachment of extensor carpi radialis longus

and flexor carpi radialis. Excise the first dorsal and first palmar

interosseous muscles. -

Release the adductor pollicis insertion

from the sesamoid at the metacarpophalangeal (MP) joint level and

reinsert it more proximally on the thumb metacarpal. Transpose skin

flaps. See Hints and Tricks box on the next page.

with good soft-tissue coverage, distraction lengthening is an effective

technique for regaining useful thumb length (8,16).

If proximal joint mobility and thenar musculature are preserved, the

patient should be able to use the thumb effectively for prehensile

activity, although it may be stiff.

-

A simple three-digit prehension pattern

may be recreated by the removal of the ring metacarpal. This procedure

increases the mobility and independence of the little-finger metacarpal. -

Flexion and closing-wedge osteotomy with

radial deviation of the base of the little-finger metacarpal may

improve pinch between the little metacarpal and the thumb metacarpal (6).

-

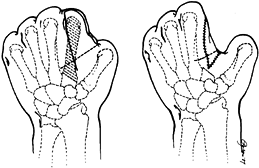

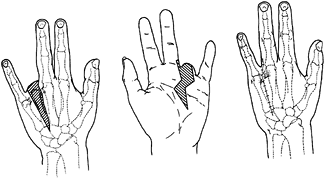

Make a longitudinal skin incision to expose the middle third of the thumb metacarpal (Fig. 46.2)

and incise the periosteum. Bunch up the skin between the pin insertion

sites such that distraction will not put undue pressure on the skin–pin

interface. Insert two parallel groups of pins transversely through the

collapsed distraction apparatus in close proximity to the intended

osteotomy site.![]() Figure 46.2. Thumb distraction lengthening in an adult. A: Place pin groups adjacent to the mid-diaphyseal osteotomy site. B:

Figure 46.2. Thumb distraction lengthening in an adult. A: Place pin groups adjacent to the mid-diaphyseal osteotomy site. B:

Once the desired distraction has been achieved, lock the bone graft

into the medullary canal of the distracted proximal segments. -

Make a transverse osteotomy through the middle third of the metacarpal.

-

Place a longitudinal pin through the

proximal and distal metacarpal segments and across the carpometacarpal

joint. By transfixing the metacarpal to the trapezium, this pin

provides resistance to the tendency of distraction to tighten the

adductor and produce secondary adduction contracture. The longitudinal

pin also prevents subluxation of the base of the thumb metacarpal on

the trapezium with distraction. -

If bone grafting is planned as a second

procedure, circumferentially incise the periosteum at the level of the

osteotomy, and then turn the screws on the distraction device to create

at least 5 mm of immediate distraction at the osteotomy site. -

If distraction osteogenesis is to be

employed, repair the longitudinal incision of the metacarpal periosteum

and then close the skin. Maintain osteotomy coaptation for 7 to 10

days, and then begin distraction of the osteotomy. Over the next 4 to 5

weeks, gradually lengthen the digit by advancing the distraction device

about 1 mm per day; do this four times a day, in ¼ mm increments. The

soft tissues will gradually stretch as the osteotomy gap is widened.

Distraction takes place along the axis provided by the longitudinal

pin. It is often possible to gain up to 3 to 3.5 cm of additional thumb

length with distraction lengthening (8,17). -

Although bone consolidation may occur

spontaneously in young patients, my custom in adults is to electively

add iliac crest bone graft to span the gap between the proximal and

distal metacarpal segments. Keep the device in place until graft

incorporation is radiographically visible. Web-space deepening, as

described above in the section on phalangization, is occasionally helpful as a secondary procedure. -

Alternatively, remove the distraction

device after distraction, and stabilize the bone graft by plate

fixation. Transfer the insertion of the adductor pollicis tendon more

proximally to help diminish the tendency of the lengthened thumb to

adduct. This allows web-space deepening without sacrificing adductor

pollicis strength.

length and mobility, it is often recommended when traumatic thumb

amputation results in basilar joint destruction (3,4,13).

The index finger is usually the digit selected for pollicization. When

the extent of trauma to the thumb has been severe enough to warrant

pollicization, the adjacent index finger is often also compromised, but

this is not necessarily a contraindication to pollicization. An injured

digit with limited mobility may be a liability in the index position

but may substantially enhance function when transposed to the thumb

position.

similar to that of pollicization for the congenitally absent or

hypoplastic thumb with individual modifications (see Chapter 69).

If there is extensive scarring and soft-tissue loss over the radial

border of the hand, preliminary flap coverage may be required.

-

Skin incisions must be individualized

when skin along the radial border of the hand is scarred. Design skin

flaps to bring the best skin—palmar, dorsal, or a combination—into the

web space created between the pollicized digit and the middle finger at

the time of closure.

P.1455

Skin graft is often necessary dorsally and radially but should be avoided in the web space. -

Evaluate digital artery integrity of the

index and middle fingers preoperatively by arteriography when there has

been proximal injury. In some instances, the vascularity to the injured

index finger may be insufficient to support disruption of collateral

flow necessitated by pollicization. In such cases, plan to use a vein

graft from the radial artery in the anatomic snuff box to the digital

arteries of the transposed digit to effect microvascular

revascularization of the digit. -

Identify and preserve the radial and

ulnar index digital nerves and arteries. Preserve the digital nerves by

splitting the common digital nerve to the index and middle fingers.

Mobilize the ulnar proper digital artery to the index by ligating the

radial proper digital artery to the middle finger. -

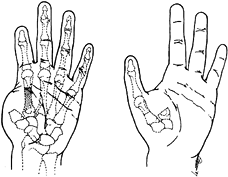

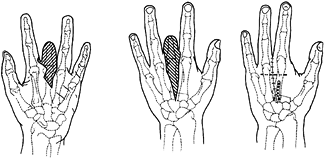

In adult pollicization, reestablish skeletal length by combining remaining thumb and index parts (Fig. 46.3).

The goal is to achieve a reconstructed thumb whose tip extends to about

75% of the length of the proximal phalanx of the middle finger. If the

index is of normal length and the thumb basilar joint is absent, use of

the rotated index metacarpal head as a trapezium will prove most

satisfactory. Figure 46.3. Pollicization of a distally amputated index finger. A: The extent of index metacarpal resection depends on the residual length of both the thumb metacarpal and the index finger. B: Fix the transposed index metacarpal to the proximal thumb metacarpal remnant.

Figure 46.3. Pollicization of a distally amputated index finger. A: The extent of index metacarpal resection depends on the residual length of both the thumb metacarpal and the index finger. B: Fix the transposed index metacarpal to the proximal thumb metacarpal remnant. -

When the trapezium and part of the thumb

metacarpal remain, resect the entire index metacarpal and an

appropriate portion of the proximal phalanx. Secure the proximal

phalanx directly on top of the thumb metacarpal remnant. When the

distal portion of the index has been damaged, retain an appropriate

metacarpal length to achieve a composite digit of proper length. Retain

the index metacarpophalangeal joint to provide thumb MP motion, while

the proximal interphalangeal joint of the index will provide an

interphalangeal joint for the reconstructed thumb. -

When the basilar joint and thenar

musculature are absent, carry out a musculotendinous rearrangement as

in pollicization for thumb aplasia. Advance the first dorsal and first

palmar interossei insertions distally on the hood and shorten the

extensor tendons. If the first dorsal interosseous muscle has been

damaged, consider simultaneous opponensplasty tendon transfer. When the

index digit is damaged distally and is merely being moved radialward

without skeletal shortening, extensor tendon shortening may not be

required. -

In adult pollicization, the flexor

tendons to the pollicized digit will not spontaneously shorten and

readapt their optimal resting length as occurs in pediatric

pollicization. Make an incision in the distal forearm and resect a

segment of index flexor tendon consistent with the extent of proximal

transposition of the pollicized index finger.

When amputation occurs at or proximal to the distal interphalangeal

joint, distal flap coverage is rarely indicated. Modest bone shortening

and contouring are usually preferable, unless the potentially

sacrificed bone length is judged critical to preservation of the

functional integrity of the affected finger.

insertion will continue to contribute effectively to grasp activity.

When amputation occurs more proximally (e.g., proximal middle phalanx,

proximal phalanx), the digit will have only limited value in the

little-finger position and will probably be a nuisance in the index

position. When amputation occurs proximal to the superficialis but

distal to the midproximal phalanx, preservation of the digit in the

middle or ring position may help prevent small objects from falling

through the hand, although only limited MP joint flexion will occur

through the pull of the intrinsic muscles.

compromised multiple digits, it is best to preserve all available bone

length. In multidigit degloving injuries, distant flap overage may be

indicated.

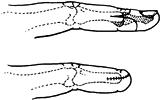

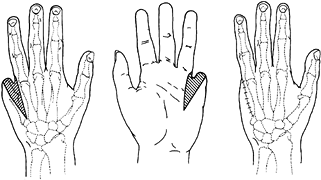

attention to bone as well as to soft tissue to avoid a bulbous distal

contour (Fig. 46.4).

|

|

Figure 46.4. Interphalangeal joint disarticulation amputation. A: Remove palmar condylar prominences. B: The greater length of the palmar flap brings the suture line away from the contact surface.

|

-

Create palmar and dorsal tongue-shaped

flaps by bilateral midlateral incisions. Make the palmar flap slightly

longer, if possible, so that the scar will be dorsal. Pull tendons

distally and divide them sharply. -

Gently divide digital nerves without

applying undue traction, and allow them to retract into proximal soft

tissues. Ligate digital arteries. -

Identify the palmar plate and excise it. Remove the cartilage from the exposed phalangeal articular surface to

P.1456

facilitate bone contouring. Resect the palmar condylar prominences in

line with the palmar cortex of the diaphysis. Shape the remaining flat

condylar surface with a rongeur and rasp to resemble a paddle. Palpate

the bone through the overlying skin to ensure that all prominences have

been relieved. -

Close the skin with interrupted sutures.

Extensive contouring of skin margins is unnecessary, since the skin

contour will gradually model to the underlying bony contour. -

Handle diaphyseal phalangeal amputations in a similar fashion.

manipulate objects. Imperfections of the index finger are, however,

poorly tolerated. When the index finger of an otherwise normal hand is

compromised by loss of length, altered sensibility, or pain, many

patients spontaneously shift to a prehension pattern that ignores the

index finger in preference of a normal middle finger. The greater

length of the middle finger allows it to meet the thumb easily for

precision activity. When a short index finger is being ignored, it is

often held in a hyperextended posture. Amputation of a short index

finger is advised when patterns of disuse become fixed.

either MP joint disarticulation or index ray resection. MP joint

disarticulation preserves the breadth of the palm, which is helpful in

stabilizing objects held with a cylindrical grip but presents an

obtrusive prominence in the web space (18). Ray resection narrows the palm and improves the appearance of the hand by achieving a broad, smooth web-space contour.

If the wedge of skin removed is too large, the distance from thumb to

middle metacarpal will be diminished and thumb abduction may be

limited. Dissect skin flaps from the index digit, taking care to

preserve flap innervation.

|

|

Figure 46.5. Index ray resection. A: Dorsal view. B: Palmar skin resection. C: Wound closure preserves sensate skin throughout the widened web space.

|

-

Divide the extensor indicis proprius

tendon from its insertion ulnar to the index communis tendon and tag

it. Apply traction to the extensor digitorum communis tendon, divide

it, and allow it to retract. -

Osteotomize the index metacarpal

obliquely through the proximal metaphysis, preserving the insertion of

the extensor carpi radialis longus and flexor carpi radialis tendons. -

Although some authors advocate suturing

the first dorsal interosseous tendon into the second dorsal

interosseous insertion on the middle metacarpal to enhance the strength

of lateral pinch, this transfer is occasionally too strong and may

result in a fixed radial deviation and lumbrical plus (see Pitfalls and Complications, below) posture of the middle finger. -

Divide the deep transverse metacarpal

ligament adjacent to the middle finger. Identify the index flexor

tendons, pull them distally, divide them, and allow them to retract

proximally. Take care in dealing with the digital nerves: The radial

nerve to the index finger must not be extensively mobilized. Sharply

divide digital nerves and allow them to retract into the soft tissue

without tension. The ultimate neuroma end of the nerves must be

distanced from further trauma. -

Remove the index finger. Sew the extensor

indicis proprius into the middle finger extensor digitorum communis

tendon at the level of its insertion to enhance independence of

middle-finger extension. Trim the first dorsal and first palmar

interosseous muscles as necessary to ensure a smooth web-space contour.

Close the skin flaps with the thumb in palmar and radial abduction.

cup small objects in the palm of the hand because of the tendency of such objects to escape from the grasp (Fig. 46.6) (4). Ray resection and reconstruction by either soft-tissue coaptation (Fig. 46.7) or ray transfer (Fig. 46.8) closes this gap and improves the aesthetic appearance of the hand (22,23). Both procedures narrow the palm and thus predictably weaken grasp and cylindrical grip palmar stabilization.

|

|

Figure 46.6. Absence of either the middle or the ring finger impairs the ability to retain small objects in the palm.

|

|

|

Figure 46.7. Ring-finger ray resection with soft-tissue coaptation sling. A:

Transverse intermetacarpal ligament and palmar plate continuity is preserved as the ring metacarpal is excised through a dorsal exposure. B: A palmar chevron incision allows resection of redundant palmar skin. C: Interweaving of the transverse intermetacarpal ligament brings the little metacarpal head toward the middle metacarpal, while dorsal skin closure stabilizes rotational alignment. |

|

|

Figure 46.8. Middle ray resection and index ray resection. A: Converging chevron incisions reduce palmar skin and soft-tissue redundancy. B: Corresponding step-cut osteotomies are fashioned in both the index and middle metacarpal proximal metaphyses. C:

The transposed index finger is fixed to the middle finger with a plate and is further stabilized with Kirschner wire into the ring metacarpal. |

Pronation strength, a measure of grip stabilization by the breath of

the metacarpal, is diminished to 50% of predicted values after index

ray resection (18). Transposition of the index

ray to the middle metacarpal position results in 75% of predicted grip

strength, while transposition of the little-finger ray to the ring

finger metacarpal position results in retention of 85% of predicted

grip strength (7).

effectively brings the relatively mobile little-finger ray into close

approximation to the middle finger but is somewhat less successful in

bringing the relatively fixed index metacarpal alongside the ring

metacarpal (23).

-

Make parallel zigzag incisions on the

palmar surface overlying the metacarpal to be resected. Remove a

generous wedge of dorsal skin. The dorsal skin resection will provide a

dermodesis, which will stabilize the digit and prevent it from rotating

into a position in which the fingers will scissor over one another in

flexion. -

Resect the entire metacarpal

subperiosteally. If the middle metacarpal is excised, preserve the

proximal insertion of the extensor carpi radialis brevis within the

periosteal sleeve, and take care to preserve the origin of the adductor

pollicis muscle. When the ring metacarpal is resected, the entire

metacarpal base may be removed, allowing radial shift of the little

metacarpal on the hamate. -

Avoid injury to the deep motor branch of

the ulnar nerve, which runs just palmar to the metacarpal and is

vulnerable to injury when excising the metacarpal. Identify and ligate

the proper digital arteries. Sharply divide the proper digital nerves

distal to the common digital nerve bifurcation. -

Pull flexor and extensor tendons

distally, divide them, and allow them to retract proximally. Divide the

interosseous and lumbrical tendons. -

Retain a single continuous soft-tissue

band, consisting of the palmar plate and the two adjacent deep

transverse metacarpal ligaments, each of which is firmly attached to

adjacent digits. Press the metacarpal heads together manually. Tightly

secure the digits adjacent to the resected metacarpal to one another by

dividing the

P.1458

ligament–palmar

plate complex and weaving the two segments together. Then securely

suture the shortened ligament–palmar plate complex with interrupted

sutures. -

Close the palmar skin incision first.

Observe the fingers with the wrist in both flexion and extension.

Assess the extent of digital scissoring, if any, as the dorsal skin is

approximated. If residual scissoring persists, excise further dorsal

skin. Circumferential dressing and splinting maintains lateral

metacarpal pressure and protects the ligament repair during the first 3

weeks after reconstruction.

retained digits is facilitated if the skin of a single web space is

preserved and shifted intact to the new web space (10,21).

If possible, base the web-space flap on the digit that is not being

transposed. For example, if the middle finger is being resected and the

index finger is being transposed to the middle-finger position, the

web-space skin of the middle–ring interval is retained based on the

ring finger and is ultimately sewn to the ulnar border of the index

finger.

-

Create palmar zigzag incisions that

converge over the middle third of the metacarpal to be resected. Resect

a dorsal wedge of skin with its apex over the proximal third of the

metacarpal. -

Identify the digital neurovascular

structures. Sharply section the proper digital nerves, and ligate the

proper digital arteries. -

Pull flexor and extensor tendons distally

and divide them. Define the interosseous muscles inserting on the

resected digit distally, dissect them free proximally, isolate them,

and excise them. Divide the lumbrical tendon along the radial aspect of

the digit being resected. -

When the middle metacarpal is resected,

preserve the origin of the adductor pollicis on the middle metacarpal

by subperiosteal dissection. -

Because nonunion of the bone-to-bone

junction between transferred and recipient rays is a common

complication of this procedure, careful planning of the bony osteotomy

and secure internal fixation are essential (10).

Transverse osteotomy through the proximal metaphysis rather than

diaphysis provides maximal cancellous surface area and thus facilitates

union. Alignment of the transferred digit is simplified by applying a T

mini-fragment plate to the intact central metacarpal before osteotomy.

Drill, tap, and secure the proximal screws, taking care to align the

longitudinal limb of the plate with the long axis of the metacarpal to

be removed. Then remove the screws and plate. -

Transversely osteotomize the metaphyseal

base of both the recipient central metacarpal and the metacarpal to be

transferred. Mobilize the transferred ray to allow transfer without

tension. The interosseous muscle origins may need to be released.

Suture the adductor pollicis origin to the ring metacarpal when the

index ray is transposed to the middle position. Precisely fit the

transferred ray onto the recipient base. Resecure the screws and plate

proximally to the central metacarpal. Align the long axis of the

transferred metacarpal to the longitudinal holes of the plate to

reproduce the alignment of the excised metacarpal. Ensure that

rotational alignment has been preserved, that the digit is clinically

straight, and that the fingers do not overlap in flexion. Secure the

shaft of the transferred metacarpal to the plate with additional screws. -

A distal transversely placed Kirschner

wire may be helpful in further stabilizing the transferred digit during

the first weeks following surgery. Approximate the deep transverse

metacarpal ligaments from the adjacent sides of the resected metacarpal. -

Transpose the little-finger metacarpal to

the ring position. The ultimate length discrepancy between the little

and middle fingers may be minimized if the osteotomy is performed more

proximally in the metaphysis of the little finger than in the

metaphysis of the ring-finger metacarpal. This technique may add up to

1.5 cm in length to the shifted little-finger ray.

The hand that has undergone little-finger ray resection has an

excellent cosmetic appearance and acceptance. For this reason, ray

resection is recommended in sedentary patients or those particularly

concerned about cosmesis. In patients who depend on the breadth of the

palm to stabilize a hammer, tennis racket, or other object with a

cylindrical grip, removing the little-finger metacarpal will result in

a significant loss of strength (11).

|

|

Figure 46.9. Little finger ray resection. A: The extensor carpi ulnaris insertion into the proximal metacarpal is preserved. B: Palmar skin excision. C: Skin closure.

|

-

Make a dorso-ulnar incision to expose the

little-finger metacarpal. Isolate and divide the extensor communis and

extensor quinti tendons. Because the extensor carpi ulnaris inserts on

the base of the little-finger metacarpal, avoid disarticulating the

carpometacarpal joint. Instead, divide the metacarpal obliquely through

the tapering metaphysis. -

Divide the flexor tendons as well as the

third palmar interosseous, lumbrical, and hypothenar muscle tendons.

Trim the hypothenar muscles as necessary to create a smooth contour

along the ulnar border of the hand. -

A third alternative, a compromise between

MP disarticulation and ray resection, involves amputating the

metacarpal head and neck and obliquely contouring the metacarpal

through the distal diaphysis. Although this procedure improves the

appearance of the hand and preserves most of the width of the palm, it

eliminates the firm stabilizing contact surface over the palmar aspect

of the little-finger metacarpal head.

out wrist disarticulation by removing the carpal bones. When the entire

length of the radius and ulna is preserved, forearm rotation is

maximized within a prosthesis. Although fitting a prosthesis is

somewhat simpler with diaphyseal forearm amputations, this advantage is

modest and is outweighed by the advantage of preserving the integrity

of the distal radio-ulnar articulation.

of a pain-free, useful hand. This goal is usually best accomplished by

early active movement of the injured hand. When internal fixation is

used, a firm construct should be designed that will permit digital

motion at the earliest possible time. The hand therapist may help guide

the patient with a recent partial hand amputation to regain useful hand

function. Emotional support should be provided by both the physician

and the therapist to help the patient adapt to the altered body image.

when the free distal end of a transected profundus tendon becomes fixed

distally and cannot move to the proximal extent of its normal excursion

(19,26).

between the profundus tendons at the wrist and distal forearm level,

limitation of motion of a single tendon may have an adverse effect on

the motion of adjacent uninjured digits. Patients who have sustained

amputation may experience limitation of active distal joint flexion in

adjacent digits and may complain of palmar or flexor forearm pain with

attempted forceful flexion. The condition is provoked by sewing the

profundus tendon over the end of a digital amputation stump. It is best

avoided by early active motion of both amputated and adjacent digits.

When quadriga is diagnosed, release of the adherent profundus tendon in

the palm proximal to the lumbrical origin will predictably relieve this

condition.

When amputation occurs through a finger proximal to the insertion of

the profundus tendon but distal to the proximal interphalangeal joint,

the proximal pull of the profundus is transmitted through the lumbrical

into the dorsal hood apparatus, increasing the force of proximal

interphalangeal joint extension. As the patient tries to grip

forcefully, the proximal movement of the profundus results in a posture

of proximal interphalangeal joint extension. This paradoxical digital

motion may be eliminated either by sectioning the profundus proximal to

the lumbrical origin or by releasing the radial lateral band.

skin, all amputations inevitably require transection of sensory nerve

branches. Neuromas occur whenever a nerve is transected and thus are an

inevitable consequence of amputation. With proper surgical and

postoperative management, however, neuromas need not be tender or

painful. When a neuroma is caught in overlying scar or is adherent to a

fixed structure, it often becomes symptomatic. The best approach is

prevention. Many initially tender neuromas improve with local massage

and desensitization activity under the guidance of a therapist. Do not

consider surgical revision of tender neuromas until the wound has

become supple and the skin is no longer adherent to underlying soft

tissue and bone.

distally and tethered by proximal joint motion. In such situations, the

nerve must be freed distally and allowed to migrate proximally. Early

digital motion is encouraged (see Chapter 53).

appearance of the residual hand. Simple procedures tend to be

associated with less residual pain than complex reconstruction.

Encourage early motion. Hand therapy may be invaluable in assisting

patients to regain function.

scheme: *, classic article; #, review article; !, basic research

article; and +, clinical results/outcome study.

E, Alnot J-Y, Coutier C, Cadot B. Résection du Quatrième Rayon pour

Lésions de l’Annulaire les Amputations du Quatrième Rayon de la Main

(Amputation of the fourth ray of the hand). Rev Chir Orthop 1997;83:324.

JF, Carman W, MacKenzie JK. Transmetacarpal Amputation of the Index

Finger: A Clinical Assessment of Hand Strength and Complications. J Hand Surg 1977;2:471.

L, Foucher G. Étude Comparative des Résections Metacarpiennes et des

Translocations après Amputations des Doigts Medians (A comparative

study of metacarpal resection and translocation after amputation of the

middle finger). Ann Chir Main Memb Super 1995;14;74.