Sternoclavicular and Acromioclavicular Joint Injuries

-

General information

-

Anatomy and mechanism.

The sternoclavicular joint is a diarthroidal joint between the medial

clavicle and the clavicular notch of the sternum. Though there is

little intrinsic osseous stability, the sternoclavicular ligaments are

reinforced by the costoclavicular ligaments, disc ligament,

interclavicular ligament, and joint capsule; thus explaining the rarity

of this injury.The sternoclavicular joint is the major articulation

between the axial and appendicular skeleton. The majority of

scapulothoracic motion occurs through the sternoclavicular joint, which

allows approximately 45 degrees of rotation around its long axis.

Injuries to the sternoclavicular joint represent only 3% of shoulder

girdle injuries (1).A sternoclavicular injury is always a high-energy event,

and, therefore, other injuries should be expected. Due to the posterior

proximity of critical structures such as the great vessels, phrenic

nerve, trachea, and esophagus, associated injuries should be diagnosed

promptly.The mechanism of injury can either be from a direct blow

to the anterior clavicle causing a posterior dislocation or an indirect

medial force vector to the shoulder. If the medial force drives the

scapula posteriorly (retracted) along the thorax, the sternoclavicular

joint dislocates anteriorly, and if driven anteriorly (protracted), the

sternoclavicular joint dislocates posteriorly. -

Classification. The joint may sustain a simple strain (Type I) which is not dislocated but painful, have subluxation (Type II), or frank dislocation (Type III), depending on the degree of ligament disruption (2). More importantly, sternoclavicular dislocations are described according to the direction of dislocation, anterior or posterior dislocation.An important point to distinguish is the possibility of

a medial clavicular physeal fracture which can displace anteriorly or

posteriorly as well, thus mimicking a dislocation. This physis does not

close until the early 20s and should be suspected under the age of 25.As an aside, there is an atraumatic type of dislocation

due to ligamentous laxity, but emphasis in this chapter will remain on

the traumatic variety.

-

-

Diagnosis

-

History and physical exam.

The history always is significant for a high-energy mechanism, usually

a motor vehicle collision. The patient should be asked about the

presence of shortness of breath and difficulty breathing or swallowing.

Hoarseness and stridor should be documented. Pain is well localized and

associated with swelling and ecchymosis. There is usually a palpable

and mobile prominence just anterior and lateral to the sternal notch in

the case of the more common anterior dislocation, or perhaps a

puckering of the skin with a sense of fluctuance due to a posterior

dislocation. Chest auscultation and a thorough neurovascular exam to

the ipsilateral extremity is important to document early. -

Radiographs. A serendipity x-ray view of the shoulder is a 40-degree cephalic tilt view centered on the manubrium (3). In this view, an anterior dislocation will be manifested with a superior appearing clavicular head.Once suspected, a computed tomography (CT) examination

with 2-mm cut intervals should also be obtained to visualize the

location and extent of

P.218

dislocation,

evaluate the retrosternal region for soft tissue injury, differentiate

between medial clavicle fractures, or possibly elucidate a physis (when

it appears above the age of 18) injury.

-

-

Treatment

-

Nonoperative.

The majority of sternoclavicular injuries are anterior dislocations,

and these should be treated nonoperativley with the expectation of good

functional results and usually with complete resolution of pain (3).

Cosmetic asymmetry will remain, closed reduction will not remain

reduced, and no brace has been proven to be efficacious in this regard.

This expectant result also holds true for the growth plate injuries

which are displaced anteriorly. -

Operative. An

acute posterior dislocation should undergo a manipulative reduction to

unlock the retrosternal clavicular head. The rationale for the need for

closed reduction relates to the concern that impingement on critical

structures may yield late sequelae from erosion or irritation (4).A pointed bone tenaculum may be useful to grab the head

of the clavicle and pull it back to its proper relation to the

manubrium. A roll between the shoulder blades while the patient is

supine, in combination with lateral traction of the abducted arm, is a

helpful adjunctive maneuver. Due to possible violation of critical

structures in the mediastinum, anesthesia should always be on hand to

manage the airway, and a thoracic surgeon should always be on standby

during the procedure. Performing the reduction maneuver under general

anesthesia with optimum airway control should be considered.Many authors have described techniques for stabilization

of the unstable sternoclavicular joint using various tendon

reconstructions and/or Kirschner wires with mixed results (5). A warning against the use of smooth wires is restated throughout the literature due to the problem of migration. -

Follow-up. A

sling may be used for 1 month to support the extremity during the acute

phase of pain during a period of relative immobility. Motion and

function should be allowed to advance as discomfort allows. Shorter or

longer periods with relative rest are required according to which type

(I, II, or III) dislocation is present. The patient may need

reassurance for months during a period of gradually resolving symptoms. -

Complications.

Retrosternal dislocations are frequently missed, likely due to the lack

of physical exam findings in the context of a multiply injured patient (6).

Missed or late diagnosis of associated injuries of the mediastinum and

brachial plexus are well documented. Failure of fixation, hardware

migration, and redislocation have also been reported after operative

stabilization and are likely due to the high forces acting on this main

articulation between the upper extremity and the axial skeleton (7).

Lastly, arthritic symptoms of the sternoclavicular joint are not

uncommon, and many authors have described resection of the clavicular

head to address refractory pain (8).

-

-

General information

-

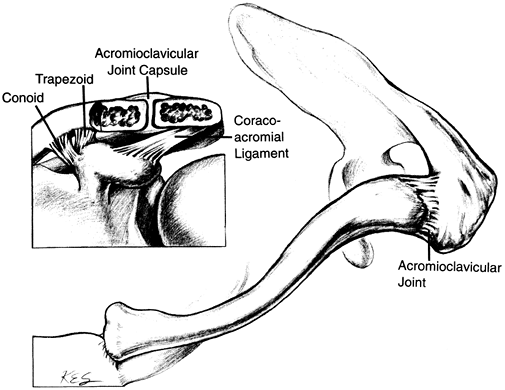

Anatomy and mechanism.

The acromioclavicular joint is a synovial, diarthroidal joint that

contains a small, round meniscus composed of fibrocartilage much like

the knee. The static linkage of the lateral clavicle to the upper

extremity is via the coracoclavicular and acromioclavicular ligaments

as well as the joint capsule. The acromioclavicular AC joint capsule is

strongest at its superior and posterior margin (9).

The scapula is suspended from the clavicle via the coracoclavicular

ligaments, which run from the base of the coracoid to the undersurface

of the clavicle (Fig. 14-1).The acromioclavicular dislocation, commonly referred to

as a shoulder separation, is a much more common injury, likely due to

its more vulnerable position on the lateral aspect of the shoulder. The

joint absorbs direct force with any blow to the shoulder such as the

most common mechanism of a fall on the shoulder. -

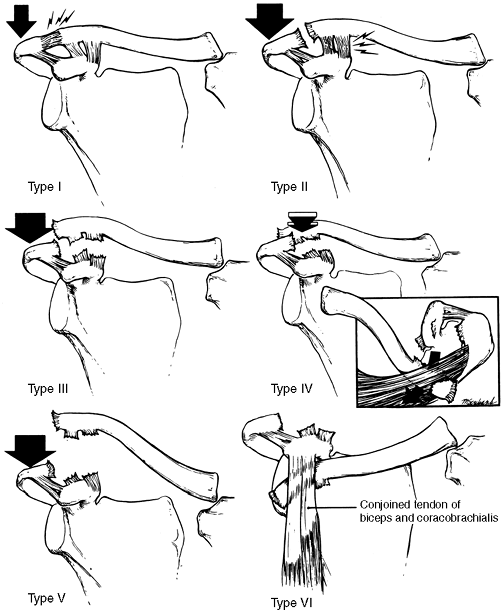

Classification (Fig. 14-2).

The Tossy classification was the first to grade acromioclavicular

dislocations (Types I–III). Rockwood modified this classification by

P.219

adding three more types (IV, V, and VI), based on directions of displacement (10). The joint may sustain a simple strain with minimal displacement referred to as a Type I. The Type II

injury is described as being displaced superiorly less than one half

the diameter of the clavicle and is thought to be associated with

complete tearing of the acromioclavicular ligaments but relative

sparing of the coracoclavicular ligaments. The Type III

dislocation represents complete disruption of the coracoclavicular and

acromioclavicular ligaments with superior displacement. A Type IV acromioclavicular dislocation is complete and displaced posteriorly; whereas a Type V

is an extreme variation of Type III, where the clavicle buttonholes

through the trapezius into the subcutaneous tissue and thus is

associated with much more stripping of trapezius and deltoid. The Type VI dislocation is an inferior dislocation under the coracoid process. Figure 14-1.

Figure 14-1.

This illustration highlights the anatomy of the acromioclavicular

joint. The joint capsule as well as the conoid and trapezoid portions

of the coracoclavicular ligament are the static stabilizers of the the

acromioclavicular joint. (From Hansen ST, Swiontkowski MF. Orthopaedic trauma protocols. New York: Raven Press, 1993:80, with permission.)

-

-

Diagnosis

-

History and physical exam.

The history usually details a fall to the shoulder, and it is

associated with well-localized pain. The acromioclavicular joint is

typically swollen and point tender. If a visual or palpable stepoff

exists, or the distal clavicle feels reducible, then there is at least

a Type II injury. In Types III to VI, the physical findings are

dramatic. -

Radiographs.

Typically, an anteroposterior x-ray of the shoulder reveals the injury,

though imaging of the joint can be enhanced with a 10-degree cephalic

tilt view. Visualization of both acromioclavicular joints on the same

large x-ray casette helps to understand relative displacement. Such a

radiograph taken with the patient hanging weights in each hand was a

popular study but has fallen into disfavor because it is painful and

does not change management. The examiner looks for increased distance

between the coracoid and the clavicle.![]() Figure 14-2. Schematic drawings of the classification of ligamentous injuries that can occur to the acromioclavicular ligament. Type I:

Figure 14-2. Schematic drawings of the classification of ligamentous injuries that can occur to the acromioclavicular ligament. Type I:

A mild force applied to the point of the shoulder does not disrupt

either the acromioclavicular or the coracoclavicular ligaments. Type II:

A moderate to heavy force applied to the point of the shoulder will

disrupt the acromioclavicular ligaments, but the coracoclavicular

ligaments remain intact. Type III: When a

severe force is applied to the point of the shoulder, both the

acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments are disrupted. Type IV:

In this major injury, not only are the acromioclavicular and

coracoclavicular ligaments disrupted but also the distal end of the

clavicle is displaced posteriorly into or through the trapezius muscle.

Type V: A violent force has been applied to

the point of the shoulder, not only rupturing the acromioclavicular and

coracoclavicular ligaments but also disrupting the deltoid and

trapezius muscle attachments and creating a major separation between

the clavicle and the acromion. Type VI:

Another major injury is an inferior dislocation of the distal end of

the clavicle to the subcoraciod position. The acromioclavicular and

coracoclavicular ligaments are disrupted. (From Rockwood CA, Williams

GR, Young DC. Injuries to the acromioclavicular joint. In: Rockwood CR,

Green DP, Bucholz RW, et al., eds. Fractures in adults, 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven, 1996:1354, with permission.)

-

-

Treatment

-

Nonoperative.

Type I and II acromioclavicular injuries should be treated

nonoperativley with the expectation of good functional results and

usually with complete resolution of pain (11).

Ice should be provided in the acute setting to relieve swelling, as

welll as to support the arm against gravity. As is the case for the

sternoclavicular dislocation, a closed reduction will not remain

reduced, and no brace has been proven to be efficacious in this regard.As for Type III dislocations, clinical studies comparing

operative versus nonoperative treatment seem to indicate that there is

no benefit from surgical treatment (11,12,13,14), though some experts believe that the overhead throwing athlete and manual laborer should undergo reconstruction (10). -

Operative.

Many surgical procedures have been described to repair an

acromioclavicular dislocation with the goal of preventing superior

migration. The strategy is either to fix the distal clavicle directly

to the acromion or to augment the coracoclavicular ligaments to

maintain a reduced joint. Some surgeons advocate a combination of these

two strategies to maintain the reduction against the great forces

acting to displace the clavicle. Though each strategy can be employed

in the acute or delayed setting, if a reconstruction is done late, it

is usually combined with a distal clavicle resection.The most widely known procedure is the Weaver-Dunn (15),

and most surgeons augment some variation of this repair with fixation

across the acromioclavicular joint, into the coracoid, or around the

base of the coracoid and clavicle like a sling. The Weaver-Dunn itself

involves bringing up the coracoclavicular ligament through the end of a

resected distal clavicle.A new device called the hook plate is gaining

popularity. The plate is fixed to the cephalad border of the distal

clavicle, and a terminal hook sweeps under the acromion so the clavicle

is restrained from springing superiorly. -

Follow-up. As

is the case with the sternoclavicular dislocation, a sling may be used

for a few weeks to support the extremity during the acute phase of

pain. A period of relative immobility is instituted, but motion is

advanced as discomfort allows. Shorter or longer periods with relative

rest are required according to which Type (I–III) of injury is present.

Often the Type I and II injuries hurt for a longer period of time than

the Type III injuries due to partial communication of the joint

surfaces and tethering of partially torn ligamentous structures. The

patient may need reassurance for months during a period of gradually

resolving symptoms. -

Complications.

Occasionaly, symptomatic posttraumatic osteolysis or arthritis of the

acromioclavicular joint develops. An arthroscopic or open resection of

the distal clavicle can be done to resect the distal 1.5 to 2.0 cm of

bone, and results have generally been favorable (16).Most of the complications related to surgery relate to

failure of fixation causing chronic symptomatic instability. Hardware

failure such as slippage of Kirschner wires or cutout of

coracoclavicular screws, as well as graft or suture cutting through the

distal clavicle, are not uncommon events and underscore the technically

demanding nature of the reconstruction.

-

-

Diagnosis: Anteroposterior shoulder radiograph, 15-degree cephalad oblique radiograph, clinical examination

-

Treatment: Grades I–III, sling for comfort for 7–10 days, then range-of-motion exercises

-

Indications for surgery: Grade IV, V, or VI injuries

-

Recommended technique: Subcoracoid suture loop with coracoclavicular (CC) ligament and deltotrapezial fascial repair

GC, Wallace WA, Stablforth PG, et al. The management of acute

acromioclavicular dislocation: a randomized prospective controlled

trial. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1989;71:848–850.

RD, Hawkins RJ, Grainger RW. A comparative analysis of operative versus

non-operative treatment of grade III acromioclavicular separations. Clin Orthop 1985;193:150–155.

SD, Baumgarten TE, Andrews JR. Arthroscopic resection of the distal

aspect of the clavicle with concomitant subacromial decompression. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2001;83:328.

MR. Complete dislocation of the acromioclavicular joint: the nature of

the traumatic lesion and effective methods of treatment with an

analysis of 41 cases. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1946;28:813–837.