SHOULDER ARTHROSCOPY

modality continues to evolve as our understanding of the anatomy and

pathophysiology of the disease processes, as well as new technologies,

allow us to treat a broader variety of shoulder ailments. Although

there are reports in the literature regarding the use of the

arthroscope in the 1930s and 1940s, it was Watanabe’s work in the 1950s

in developing more practical arthroscopic instrumentation that

ultimately led to the development of routine knee arthroscopy in the

1970s (4). The routine use of the arthroscope

in the shoulder lagged behind its use in the knee, but by the early

1980s its benefits as a less invasive surgery for the shoulder were

clearly established. It was during the late 1970s and early 1980s that

shoulder arthroscopy expanded its applications from that of diagnosis

to that of treatment (2). Many procedures such

as subacromial decompression, distal clavicle excision, and instability

and rotator cuff repairs, which previously required open surgical

incisions, could now be treated effectively with the use of shoulder

arthroscopy.

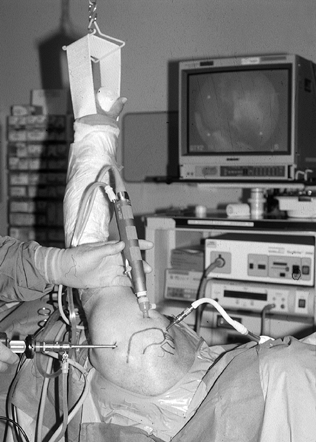

operating room table that allows adjustments for height;

flexion/extension of the head, torso, and legs; and tilt in the long

and short planes of the table. Typically, the video monitor, recorder,

and printer are stored in a cabinet that allows easy viewing by all

operating room personnel.

with a fluid medium. Normal saline is the fluid most commonly used, as

it has demonstrated no harmful effects on articular cartilage or from

systemic absorption. Both static (i.e., gravity-assisted) and

arthroscopic pump systems are available and can be used according to

the surgeon’s preference (3).

by the large variety of mechanical instrumentation available today.

Mechanical shavers, burrs, and resectors can all assist the surgeon in

treating the intraarticular as well as extraarticular conditions. The

ability to use electrocoagulation and cautery in a fluid medium was an

important advance for shoulder arthroscopy. While capillary oozing is

readily controlled by the hemostatic pressure within the glenohumeral

joint from either a pump or gravity system, the surgical electrode is

extremely valuable for procedures within the subacromial space, where

excessive bleeding from the coracoacromial artery is sometimes

encountered.

instruments in knee arthroscopy, have also been developed for the

shoulder. Basket forceps, grasping forceps, curets, and probes are but

a few of those available.

the lateral decubitus position and the beach-chair position. Each

position has advantages and disadvantages, and most surgeons choose the

one they are most comfortable with, which is frequently the one they

trained with. Proponents of the lateral position feel the continuous

traction allows easier glenohumeral and subacromial arthroscopy.

Proponents of the beach-chair position argue that it is more convenient

for regional anesthesia and when converting to open procedures. I

prefer the lateral decubitus position for most shoulder cases but

occasionally utilize a beach-chair position if the possibility of an

open capsular repair exists. The alternative is to reprep and redrape

after the arthroscopy is performed in the lateral position.

-

For the lateral decubitus position, place

the patient on a standard operating table that is equipped with a bean

bag. Kidney rests, adhesive tape, and thorax-positioning devices can be

utilized to further stabilize patients after they are turned onto their

side and after placing a padded roll to protect the neurovascular

structures of the axilla. -

Flex the down-side leg at the hip and the

knee, and tape over the pelvis, securing it to the operating room table

to further stabilize the patient. Place a pillow between the legs.

Protect the peroneal nerve and malleoli of the down-side leg. Flex the

dependent arm forward. -

Flex the elbow, supporting it on a padded

arm board. Support the cervical spine to prevent hyperextension that

might cause a cervicobrachial radiculopathy. Tilt the torso 30°

posteriorly to bring the glenohumeral joint horizontal with the floor. -

Place a plastic adhesive U-drape

proximally, from a line just medial to the vertebral border of the

scapula posteriorly, over the medial third of the clavicle superiorly

and medial to the coracoid process anteriorly. Then place another

smaller plastic adhesive drape across the ends of the U-drape at the

mid-thorax level. -

Traction may be applied to the arm with

various commercial devices. Secure the traction apparatus to the

operating table in a position that allows abduction and forward

flexion. Then various forms of skin traction can be applied to the

forearm and hand. I prefer to wrap the hand and forearm with cotton

cast padding (Webril), followed by reusable adhesive strips on the

volar and dorsal forearm, with a loop around the hand to allow

subsequent placement of a Z-hook and an S-hook, which can be attached

to the traction apparatus. -

Secure the adhesive strips with elastic

adhesive wrap (Coban) around the forearm. Place the remaining roll of

Webril in the patient’s palm to support the fingers. Do not exceed

10–15 lbs longitudinal traction, and adjust the traction weight

downward depending on the individual patient. I most commonly use 7½

lbs.

surgeon when the patient is in the lateral decubitus position, but it

generally ranges from 20° to 70° of abduction and from 10° to 20° of

forward flexion. In addition, a stack of towels or an assistant’s hand

can help provide a perpendicular translation force when placed between

the chest wall and the proximal humerus.

easier diagnostic and arthroscopic procedures, many feel it is more

difficult when converting to open procedures, especially open anterior

capsular shifts and large rotator cuff tears. These surgeons employ a

beach-chair position if conversion to an open procedure is anticipated.

I have found that a capsular shift procedure can be performed without a

reprep and redrape if the bean bag is deflated, the patient is allowed

to fall back to a semisupine position, and the arm is rewrapped with a

sterile cover. Only rarely is a complete reprep and redrape required.

In addition, most open rotator cuff repairs can be performed simply by

releasing traction, covering the hand and forearm with a sterile wrap,

and either keeping the patient in the lateral position or deflating the

bean bag and allowing her to fall back to a semisupine position.

the glenohumeral joint, the subacromial space, and the

acromioclavicular (AC) joint.

used: a posterior portal and an anterior portal. Multiple variations of

the anterior portal have been described.

-

Before making skin incisions, be sure to

outline the anatomic landmarks. Begin with the posterior angle of the

acromion, which is subcutaneous and can be easily palpated in most

patients. From this point, draw a line along the posterior acromion

extending medially for a short distance, and anteriorly for a short

distance along the lateral edge of the acromion. The angle formed is

usually slightly obtuse rather than 90°. -

Identify the supraclavicular fossa by

placing a thumb in the quadrangular space formed by the clavicle

anteriorly, and the acromion laterally and posterolaterally. -

Place a circle over the coracoid process anteriorly, and draw in the coracoacromial ligament.

-

Finally, estimate the position of the AC joint, which can be difficult in patients with arthritic changes (Fig. 77.1).

Figure 77.1. Setup for glenohumeral portal.

Figure 77.1. Setup for glenohumeral portal. -

The entry portal is posterior, which

provides adequate visualization of the glenohumeral joint and also

allows placement of the other portals under direct arthroscopic

visualization. Place the posterior portal in what has been described as

the soft spot, or the posterior glenohumeral joint line, which

typically is 2 cm inferior and 1 cm medial to the posterolateral corner

of the acromion. Locate the soft spot by grabbing the humeral head with

your hand, using the thumb to palpate the posterior glenohumeral joint

line and the long finger to palpate the anterior glenohumeral joint

line. Typically, one can translate the humeral head back and forth to

confirm the position of the joint line. -

Make a 3–5 mm incision along Langer’s

lines through skin and subcutaneous tissues, being careful not to

penetrate the deltoid muscle. With a blunt trocar in the arthroscopic

cannula, advance in the direction of the coracoid through the deltoid

muscle, through the infraspinatous and teres minor interval, to the

posterior joint line. The blunt tip of the trocar can be used to

palpate the curve of the humeral head and the stepoff of the posterior

glenoid, and the interval of the joint line in between. -

The joint capsule will be soft with some

elasticity, as opposed to the hard surfaces of the humeral head and the

glenoid. With the nondominant hand around the cannula at skin level,

use your dominant hand to advance the trocar through the capsule, which

will be accompanied by a slight pop. Use the nondominant hand to

prevent overpenetration, and also for more precise control of the

trocar as it enters the joint. Some surgeons prefer to use a spinal

needle first to access the joint. They can then confirm intraarticular

placement of the needle by injecting 30–40 ml of saline through a

syringe, and noting the resistance to injection and backflow from the

needle after removal of the syringe. In the intact joint, the

resistance slowly increases as fluid is injected, and the syringe can

be removed after 15–20 ml have been inserted. -

After entering the joint, perform a

diagnostic arthroscopy. Some surgeons create an anterior portal at this

point to create an outflow and to allow the insertion of

instrumentation to assist with the diagnostic portion of the procedure.

arthroscope increased, so did the number of anterior portals described

by various authors. The most frequently used anterior portal allows

anterior instrumentation and visualization of the posterior portion of

the joint. There are multiple techniques for creating this anterior

portal. Most are performed under direct arthroscopic visualization with

either an outside-in or an inside-out technique. While viewing with the

arthroscope from the posterior portal, the interval in which the

anterior portal will be established is a triangle formed by the long

head of the biceps, the superior border of the subscapularis tendon,

and the glenoid (3).

skin incision directly in line with the arthroscope, which, if it is

looking at the interval above, will be just lateral and slightly

superior to the tip of the coracoid process. Some surgeons use a spinal

needle to enter the joint prior to making the skin incision. An

incision should never be made inferior or medial to the tip of the

coracoid as this could potentially injure the neurovascular structures

in the axillary sheath (4).

-

At this point, shift your view to the

video camera screen, which is still looking at the triangle formed by

the superior border of the subscapularis tendon, the long head of the

biceps tendon, and the glenoid. -

Advance the plastic cannula slightly to

see an indentation of the anterior capsule in or near the superior

aspect of the triangle above and make minute adjustments in the

position or angle of the plastic cannula before advancing it under

direct visualization into the joint. Alternatively, use an inside-out

technique with the arthroscope and a Wissinger rod. -

Advance the arthroscope into the superior

aspect of the previously mentioned triangle, and maintain the cannula

in this position. -

Remove the scope from the cannula and

place a Wissinger rod through the cannula, the joint, and the anterior

deltoid; tent the skin. Now make the skin incision, and further advance

the rod. Place the plastic cannula over the Wissinger rod and

retrograde it into the joint. Remove the Wissinger rod and reintroduce

the arthroscope to the posterior portal.

the superior portal. This portal is used must less frequently than the

anterior and posterior portals. It is created in the supraclavicular

fossa, bounded by the distal clavicle and the AC joint anteriorly, the

acromion laterally, and the base of the spine of the scapula

posteriorly (4). This portal can be used for

inflow, as well as to view the posterior glenoid labrum, the posterior

portion of the humeral head, and, with a limited view, the rotator

cuff. It is a relatively safe portal; the only structure at risk is the

suprascapular nerve, which is about 3 cm inferior to the intended

course of the instrumentation.

-

Palpate the skin approximately 1 cm

medial to the acromion in the soft spot of the supraclavicular fossa.

Then introduce a spinal needle at an angle of 40°, aiming slightly

lateral and posterior, with the intention of entering the joint

posterior to the attachment of the long head of the biceps and above

the posterior superior glenoid rim. -

Make a small skin incision and pass a

blunt trocar through the trapezius, the muscular portion of the

supraspinatus, and the superior joint capsule into the glenohumeral

joint. -

With the posterior portal, the nerves at

risk for injury are the suprascapular nerve medially and the axillary

nerve inferiorly. The suprascapular nerve lies approximately 2 cm

medial to the posterolateral glenoid, travelling in the spinoglenoid

notch. The axillary nerve travels through the quadrangular space at the

inferior border of the teres minor, which is approximately 2–4 cm

inferior to the portal placement as described. -

With the classic anterior portal, as long

as you stay lateral to the coracoid process, the chances of a severe

neurovascular injury are minimized. The cephalic vein is located

anterior and lateral to the anterolateral acromion and is rarely

injured with these techniques.

the superior surface of the rotator cuff, the undersurface of the

acromion (particularly the anterior inferior surface), and the

coracoacromial ligament, and they allow access to the AC joint.

subacromial space from the lateral aspect of the shoulder. They can

range anywhere from the anterior edge to the posterior edge, but they

all must be at least 2 cm lateral to the lateral edge of the acromion

to allow access to its entire undersurface. They should not be more

than 3 cm from the lateral edge of the acromion, as the risk of

injuring the axillary nerve increases. Anterolateral, mid-lateral, and

posterolateral portals can be used, depending on whether you need

access to the AC joint (anterolateral) for distal clavicle excisions

and subacromial decompressions, or the superior surface of the rotator

cuff (mid-lateral) for rotator cuff repairs, or even accessory portals

(posterolateral) if additional outflow is needed.

-

To introduce a blunt trocar and scope

cannula into the subacromial space, use the skin incision and the

deltoid perforation from the primary posterior portal as described for

the glenohumeral arthroscopy. Aim the scope cannula and blunt trocar

slightly superior and toward the central aspect of the undersurface of

the acromion. -

Use the blunt trocar to palpate the

undersurface of the acromion, and distend the space with fluid through

the cannula. Alternatively, using a syringe, inject 30 cc from a

lateral approach prior to advancing the scope cannula. Fluid egress

when the blunt trocar is removed provides confirmation. -

Under direct visualization, establish a

lateral portal with a 5.5 mm plastic cannula through which

instrumentation can be passed. -

Not uncommonly, the subacromial space is

severely scarred and inflamed so that visualization is obscured. When

this occurs, place a shaver or synovial resector through the lateral

portal, with its teeth facing upward against bone, and begin shaving

with an anterior to posterior sweeping motion until landmarks come into

view. Similarly, the hypertrophied bursal tissue can be removed from

the superior surface of the rotator cuff with gentle sweeping motions

in an anterior to posterior direction. -

Considerable bleeding can be encountered, especially from the inflamed bursal tissues, so be prepared with

P.2083

electrocautery to assist with hemostasis. Once the bursal space is

cleared, you should be able to visualize the superior surface of the

rotator cuff from the AC joint to a point distal and lateral to the

greater tuberosity.

a thick periosteal layer, and the anterior third is covered by the

fibers of the coracoclavicular ligament, which attach under the

anterior edge of the acromion, thereby forming the anterior roof of the

acromial arch (6). The ligament is 2–3 cm wide at its acromial insertion.

-

Begin the diagnostic arthroscopy with the

patient in a lateral decubitus position, after entering the

glenohumeral joint through the posterior portal and establishing an

anterior portal for outflow and instrumentation. A nerve hook can be

placed through the anterior cannula to assist with the procedure.

Institute a systematic approach for reviewing the intraarticular

anatomy of the shoulder, to avoid missing any abnormalities. Keep the

orientation of the glenoid surface, as viewed on the video monitor,

parallel to the floor, with the humeral head superior, the glenoid

inferior, and the biceps tendon perpendicular and between the two (6).

The initial view will allow inspection of the biceps tendon from the

passage through the rotator cuff interval to its attachment to the

superior labrum at the supraglenoid tubercle. -

Inspect the humeral head for articular

surface defects, such as that seen with a Hill-Sachs lesion on the

posterior superior humeral head. Do not confuse the Hill-Sachs lesion

with the normal intracapsular portion of the humeral neck that is

devoid of cartilage, the so-called anatomic bare patch. Also inspect

the articular surface of the glenoid, remembering that a pitted area,

less than 10 mm and with smooth chondral margins, is a normal finding

in many older individuals (5). At this point,

you may continue the arthroscopy in a posterior to anterior direction,

or, as I prefer, in an anterior to posterior direction. -

Inspect the superior and anterior glenoid

labrum. There is considerable anatomic variation in both the size and

the attachments to the labrum. Inspect the insertion of the biceps

tendon into the glenoid labrum for fraying or detachments, especially

superior labral tears from anterior to posterior (SLAP lesions) (6) (Fig. 77.2; see also COLOR FIG. 77.2).![]() Figure 77.2. (See COLOR FIG. 77.2.) Superior labral tear from anterior to posterior (SLAP lesion).

Figure 77.2. (See COLOR FIG. 77.2.) Superior labral tear from anterior to posterior (SLAP lesion). -

Next, inspect the anterior glenoid labrum

for fraying, and probe for possible detachments from the anterior

glenoid neck, which, when associated with a history of dislocation, is

called a Bankart lesion. When viewing the anterior superior labrum,

make a mental note of a normal anatomic variant, in which the middle

glenohumeral ligament forms a cordlike structure that is contiguous

with the anterosuperior labrum, forming a foramen of variable size

between the ligament and the labrum (6). -

Inspect the anterior glenohumeral

ligaments, which are thickened portions of the anterior capsule and can

be quite variable. The superior glenohumeral ligament is the most

difficult to visualize arthroscopically. It appears as a confluence of

the capsule at the inferior edge of the rotator interval, and it is

frequently obscured by the biceps tendon.

it typically passes the superior border of the subscapularis in an

obliquely vertical manner (at approximately 45°) to insert on the

superior glenoid. It can vary from being very discrete to absent, with

a range of variations between (3). The inferior

glenohumeral ligament is the most constant and clinically significant

of the glenohumeral ligaments. It has been described as a suspensory

sling that stabilizes the joint. It originates along the anterior and

inferior labrum and attaches along the anteroinferior portion of the

humeral neck. Its origin has been called a labrocapsular complex, which

describes the confluence of the inferior glenohumeral ligament, the

anterior inferior glenoid labrum, and the periosteum of the

anteroinferior glenoid. The axillary recess, or inferior recess, is a

loose outpouching of the capsule and synovium inferior to the humeral

head. It is a lax portion of the inferior glenohumeral ligament between

the antero- and posterosuperior bands.

intraarticular or undersurface of the rotator cuff. The rotator cuff is

made up of the tendons of the subscapularis, the supraspinatus, the

infraspinatus, and the teres minor. The tendon of the subscapularis,

located anteriorly, has already been inspected. The tendon of the

supraspinatus is located adjacent and slightly posterior to the long

head of the biceps.

-

Inspect the insertion of the

supraspinatus by following the long head of the biceps laterally. The

insertions of the infraspinatus and teres minor are located posterior

and inferior to the insertion of the supraspinatus. Abnormalities of

the rotator cuff can range from fraying, or partial-thickness tears

seen only on the undersurface (glenohumeral side), to full-thickness

tears seen both on the undersurface and on the superior surface when

viewed from the subacromial space.

-

Upon completion of the glenohumeral

arthroscopy, withdraw the arthroscope after allowing the outflow to

drain the shoulder joint. Insert a blunt trocar into the cannula and,

using the same posterior portal skin incision, insert the arthroscope

into the subacromial space as previously described, again aiming

superior and for the midportion of the acromion. It is sometimes useful

to use a sweeping motion of the cannula on the undersurface of the

acromion to break up any adhesions that might be there. -

Remove the blunt trocar and insert the

arthroscope with inflow attached. Orient the camera with the acromion

at the top and the rotator cuff at the bottom of the screen. In some

patients, there will be a distinct subacromial space and viewing will

be easy. A normal subacromial space will have a thin, smooth bursal

layer on the superior surface of the rotator cuff (1). The undersurface of the acromion will have a thin periosteal layer (Fig. 77.3) Figure 77.3. Subacromial space with bursal layer.

Figure 77.3. Subacromial space with bursal layer. -

In patients with chronic impingement

syndrome, the subacromial space can be difficult to visualize and may

have a cobweb appearance from adhesions. In this situation, establish

an anterolateral portal using the 5.5 mm plastic cannula with the

orange-colored trocar, aiming perpendicular to the arthroscopic cannula

and slightly in front of it. When the orange trocar comes into view,

insert a shaver under direct visualization. With the blades positioned

toward the undersurface of the acromion, remove the scarred tissues in

a controlled and safe manner. -

Identify the anterior inferior surface of

the acromion, the coracoacromial ligament, the AC joint medially, the

superior surface of the rotator cuff as far lateral as possible, and

especially the supraspinatus tendon near its musculotendinous junction.

Frequently, a probe can be used from the anterolateral portal to help

identify delaminations in the tendon or longitudinal tears that are not

immediately obvious. -

Close the portals with simple nonabsorbable sutures or subcuticular sutures, depending on your preference.

-

After diagnostic procedures, encourage

the patient to begin range-of-motion exercises of the shoulder, elbow,

wrist, and hand on the first postoperative day; the patient should also

discard the sling when comfortable, typically within a week or by the

first postoperative visit. Slowly reintroduce functional and

recreational activities once motion and strength are regained.

-

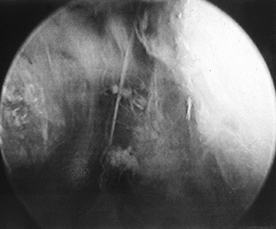

The AC joint is most commonly approached

from the same portals as used for subacromial procedures, although

separate transcutaneous portals specifically for the AC joint have been

described. Place lumbar puncture needles either in the AC joint itself,

or use to outline the anterior and posterior border of the joint (Fig. 77.4; see also COLOR FIG. 77.4). To aid in visualization of the distal clavicle, remove fibrosis or hypertrophied bursal tissue in the subacromial space.![]() Figure 77.4. (See COLOR FIG. 77.4.) Localizing the acromiocla-vicular joint.

Figure 77.4. (See COLOR FIG. 77.4.) Localizing the acromiocla-vicular joint. -

Because most arthroscopic AC joint

procedures are performed in conjunction with a subacromial

decompression, next remove the periosteal tissue on the undersurface of

the acromion, the coracoclavicular ligament, and bone from the

anteromedial border of the acromion to the posteromedial border. Once

this bone is removed, the distal clavicle can be easily visualized. -

Approach the resection of the distal

clavicle from the lateral approach or from the anterior approach. I

perform the procedure from the lateral approach, with the arthroscope

in the posterior portal and the instrumentation in the lateral portal.

With an assistant pushing down on the superior surface of the distal

clavicle, push the tip of the arthroscopic burr directly into the

middle of the face of the distal clavicle to a depth of approximately

5–6 mm, depending on the patient. Using circular movements, enlarge the

hole until the entire distal clavicle bone has been removed. The

superior AC joint capsule and ligaments should remain intact. The goal

is to create a space that is approximately 1 cm in width between the

medial edge of the acromion and the cut surface of the distal clavicle (3). Alternatively, place the burr through the anterior portal and remove bone in an anterior to posterior direction.

arthroscopy, they have realized the benefits of avoidance of deltoid

detachment as well as early return of function associated with

arthroscopic acromioplasty. Typically, this procedure is performed

after a thorough glenohumeral joint and subacromial space arthroscopy,

and after the diagnosis of impingement syndrome has been confirmed.

-

Use the same portals as for the

subacromial space arthroscopy, specifically the posterior and the

anterolateral or mid lateral. I prefer to view the procedure with the

arthroscope in the posterior portal and instrumentation inserted

through the anterolateral or mid lateral portal. -

Insert a blunt instrument through the

lateral portal and confirm the bone outlines of the anterior,

anterolateral, and lateral acromion. Then insert an electrocautery

device and incise the thickened periosteal tissues on the undersurface

of the anterior acromion, as well as the hypertrophied coracoacromial

ligament. -

When incising the coracoacromial

ligament, a vessel is frequently encountered that can cause bleeding,

which makes visualization difficult. At this point, advance the

arthroscope with the inflow attached as close to the vessel as

possible, providing a tamponade effect, and coagulate it with the

electrocautery. -

Insert an arthroscopic shaver, typically

a full-radius resector, through the lateral portal and remove the

previously incised soft tissue. Expose the entire bone undersurface of

the anterior acromion. Follow with a 5.0 mm arthroscopic oval burr. The

goal is to remove enough bone to prevent further impingement, although

surgeons differ as to what the actual amount is. I strive to remove at

least a burr’s width (5.0 mm) of bone from the projected undersurface,

noting that frequently an anterior hook to the acromion requires

additional bone removal. I begin by going from lateral to medial on the

acromion, thereby allowing easier access to the medial structures.

Sweep the burr from anterior to posterior, removing progressively less

bone posteriorly. Typically, the distance of bone removal from anterior

to posterior is around 2.0 cm. Medially, you should see the clavicular

facet of the acromion.

As the experience of surgeons and the development of instruments have

improved, so has the ability to use the arthroscope to treat these

conditions. Shoulder instability, glenoid labrum injuries, and many

rotator cuff tears can now be approached with an arthroscope and/or

limited incision techniques. Laser and radiofrequency devices are being

applied with encouraging short to midterm results.

synovectomy, biopsy, irrigation and debridement for infection, and

treatment of refractory adhesive capsulitis.

scheme: *, classic article; #, review article; !, basic research

article; and +, clinical results/outcome study.