Rheumatoid Arthritis

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Gregory Gebauer MD, MS

John J. Hwang MD

Description

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic, systemic, autoimmune

inflammatory disease affecting synovial joints and extra-articular

systems, including the skin, eyes, cardiovascular system,

bronchopulmonary system, spleen, and nervous system.

inflammatory disease affecting synovial joints and extra-articular

systems, including the skin, eyes, cardiovascular system,

bronchopulmonary system, spleen, and nervous system.

Epidemiology

Incidence

Affects 1% of the population (1)

Prevalence

-

Variable onset, but most frequently between the ages of 35 and 50 years

-

Females are affected 2–3 times more frequently than are males (1).

Risk Factors

-

Genetic predisposition is a risk factor.

-

A higher risk also exists among certain Native American populations.

Genetics

Family studies indicate a genetic predisposition, although it is multifactorial.

Etiology

-

T-cell–mediated disease of unknown origin

-

Probably a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental factors causing a systemic autoimmune disorder

Associated Conditions

-

Felty syndrome

-

Chronic rheumatoid arthritis

-

Splenomegaly

-

Neutropenia

-

On occasion, anemia and thrombocytopenia

The diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis is often complex

and requires the integration of history, physical examination, and

laboratory studies.

and requires the integration of history, physical examination, and

laboratory studies.

Signs and Symptoms

-

Rheumatoid arthritis is characteristically bilateral and symmetric.

-

Initial symptoms include swelling and morning stiffness lasting up to 1 hour or more.

-

In 2/3 of patients, symptoms begin with

fatigue, anorexia, generalized weakness, and vague musculoskeletal

symptoms until synovitis becomes apparent. -

Pain, swelling, and tenderness are localized to the joints; pain is aggravated by movement.

-

Typically, the wrist and MCP joints are affected 1st, followed by PIP and then DIP involvement.

-

Synovitis of the wrist is an almost uniform feature.

-

An isolated foot problem, such as

nonspecific inflammation of forefoot or hind foot, may be the only

symptom in early stages of the disease. -

Extra-articular manifestations include:

-

Rheumatoid nodules

-

Rheumatoid vasculitis

-

Pleuropulmonary disease

-

Neuropathy

-

Pericarditis

-

Osteoporosis

-

Congestive heart failure

-

-

Deformities of the wrists and hand occur late, after the hypertrophic synovium has destroyed the capsuloligamentous structures.

-

Chronic, progressive deformities of ulnar subluxation occur at the MCP joints.

-

The deformities in the digits are caused by displacement or rupture of the normal tendon anatomy.

History

The disease often is insidious in onset, with the gradual development of generalized symptoms and joint aches and stiffness.

Physical Exam

-

The presentation of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory arthropathies is variable and subtle.

-

Important aspects on the physical examination include:

-

Joint effusion

-

Boggy synovium

-

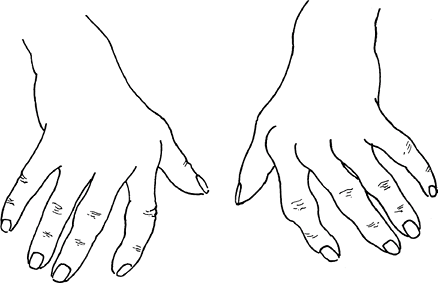

Ulnar drift of the fingers (Fig. 1)

-

Subluxation of the MCP joint

-

Painful, restricted ROM of joints

Fig. 1. The hand in rheumatoid arthritis is characterized by MCP fullness and ulnar deviation.

Fig. 1. The hand in rheumatoid arthritis is characterized by MCP fullness and ulnar deviation.

-

Tests

Lab

-

No test is specific for the diagnosis, although serum rheumatoid factor is present in 2/3 of patients.

-

Normochromic, normocytic anemia occurs.

-

Increased ESR and C-reactive protein are seen in nearly all patients.

-

These levels can be followed as a marker of disease progression and the efficacy of therapy.

-

-

Synovial fluid analysis confirms an inflammatory arthritis, but it is nonspecific.

-

Additional rheumatologic studies,

including hepatitis profile, antinucleic antibodies,

anti-double-stranded DNA, anti-Smith (and anti-Jo-1 antibodies), also

should be analyzed to exclude the possibility of other rheumatologic

processes.

Imaging

-

Imaging is not helpful early in the

disease, but, as the disease progresses, loss of articular cartilage,

bone erosions, and juxtaarticular osteopenia are seen on roentgenograms

of the affected joints. -

Plain radiographs show subluxed or dislocated MCP or PIP joints.

Pathological Findings

Chronic inflammation of the synovial tissue with subsequent bone and cartilage destruction.

Differential Diagnosis

-

Osteoarthritis

-

Acute rheumatic fever

-

Ochronosis

-

Systemic lupus erythematosus

-

Polymyalgia rheumatica

-

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

-

Spondyloarthropathies

-

Psoriatic arthritis

-

Infectious arthritis

P.359

General Measures

-

Early involvement of a rheumatologist can be helpful in making the diagnosis and managing the patient.

-

Management involves an interdisciplinary approach to relieve pain, reduce inflammation, and maintain function.

-

Multiple classes of medication may be used alone or in combination to decrease inflammation and help control pain.

-

Surgical treatment should be considered at any time to maximize the treatment.

-

Any patient who may need surgery must have a thorough examination of the cervical spine (2).

-

The cervical spine is involved in up to 90% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

-

Instability of the cervical spine,

including atlantoaxial subluxation and basilar invagination, is a

common result of pannus formation, with bone erosion and ligament

attenuation.

-

Activity

The patient’s activities should be as-tolerated, and patients are encouraged to have as active a lifestyle as possible.

Special Therapy

Physical Therapy

-

To maintain strength and ROM of affected joints

-

Does not modify the natural history of the disease process

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Additional research is needed to determine if complementary approaches are effective in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (3).

Medication (4)

-

The goal of medication is to decrease inflammation, preserve joint function, and reduce pain.

-

Many of these medications require careful monitoring of the patient.

First Line

-

NSAIDs

-

Glucocorticoids

-

Methotrexate

Second Line

-

Anti-TNF agents

-

Immunosuppressive medications, such as azathioprine and cyclophosphamide

-

Disease-modifying drugs, such as gold compounds, d-penicillamine, antimalarial agents, and sulfasalazine

Surgery

-

Synovectomy has been useful in some

patients with persistent pain secondary to severe synovitis when no

substantial joint destruction is present. -

Early tenosynovectomy of certain joints prevents tendon rupture.

-

In patients with severely destroyed

joints, arthroplasties and total joint replacements have been

successful in relieving pain, especially in the hips and knees. -

Selected fusion in the foot and ankle also is effective in relieving pain and in improving walking ability (5).

-

Treatment of rheumatoid hand disorders is complex and involves realignment, arthroplasty, tendon repair, and fusion (6).

Disposition

Issues for Referral

-

A multidisciplinary approach to the patient should be used.

-

In addition to the patient’s primary

physician, rheumatology and orthopaedics should be involved, as well as

other specialties as needed.

-

Prognosis

-

No cure exists for rheumatoid arthritis; the goal is management and delay of disease progression.

-

Some surgical treatment (e.g., synovectomy in the upper extremity) can slow the progression of disease.

-

Fluctuating disease activity makes prediction of disease behavior difficult.

-

At 10–12 years after diagnosis, <20% of patients have no evidence of disability or deformity (7)

-

Median life expectancy is shortened by 3–7 years (1).

Complications

-

Variable, depending on the treatment chosen

-

A complication of newer TNF inhibitors is serious infection (8).

Patient Monitoring

-

Monitoring occurs on an individual basis and also depends on treatment.

-

Several medications used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis require close monitoring.

References

1. Alamanos Y, Drosos AA. Epidemiology of adult rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev 2005;4:130–136.

2. Kim DH, Hilibrand AS. Rheumatoid arthritis in the cervical spine. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2005;13:463–474.

3. Ernst E. Musculoskeletal conditions and complementary/alternative medicine. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2004;18:539–556.

4. American

College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis

Guidelines. Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: 2002

update. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:328–346.

College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis

Guidelines. Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: 2002

update. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:328–346.

5. Jaakkola JI, Mann RA. A review of rheumatoid arthritis affecting the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int 2004;25:866–874.

6. Ghattas L, Mascella F, Pomponio G. Hand surgery in rheumatoid arthritis: state of the art and suggestions for research. Rheumatology 2005;44:834–845.

7. Goronzy

JJ, Weyand CM, Anderson RJ, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Klippel

JH, ed. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases, 12th ed. Atlanta: Arthritis

Foundation, 2001:209–232.

JJ, Weyand CM, Anderson RJ, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Klippel

JH, ed. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases, 12th ed. Atlanta: Arthritis

Foundation, 2001:209–232.

8. Bongartz

T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, et al. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in

rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and

malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful

effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2006;295:2275–2285.

T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, et al. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in

rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and

malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful

effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2006;295:2275–2285.

Additional Reading

Firestein GS. Etiology and pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Harris ED, Jr, Budd RC, Genovese MC, et al., eds. Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology, 7th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2005:996–1042.

Genovese MC, Harris ED, Jr. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Harris ED, Jr, Budd RC, Genovese MC, et al., eds. Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology, 7th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2005:1079–1100.

Harris ED, Jr. Clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Harris ED, Jr, Budd RC, Genovese MC, et al., eds. Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology, 7th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2005:1043–1078.

Sayah A, English JC, III. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;53:191–209.

Codes

ICD9-CM

714.0 Rheumatoid arthritis

Patient Teaching

It is important for the patient to understand the nature of this disease and the treatment options.

Activity

Patients should continue with their normal activities as much as can be tolerated.

Prevention

Careful observation of symptoms and adherence to treatment regimens can help prevent flare-ups.

FAQ

Q: Is there a cure for rheumatoid arthritis?

A: No, but disease progression can be controlled with medications.

Q: What medications will I be taking?

A:

Anti-inflammatory medications are the mainstay of treatment.

Glucocorticoids and methotrexate also are commonly used. Additional

medications may be used as indicated.

Anti-inflammatory medications are the mainstay of treatment.

Glucocorticoids and methotrexate also are commonly used. Additional

medications may be used as indicated.

Q: What can I do to help prevent progression of the disease?

A:

Compliance with prescribed medications helps to reduce inflammation and

prevent disease progression. Physical therapy and exercise help

preserve joint motion and overall health.

Compliance with prescribed medications helps to reduce inflammation and

prevent disease progression. Physical therapy and exercise help

preserve joint motion and overall health.

Q: Is my family at increased risk of the disease?

A:

An increased incidence of rheumatoid arthritis occurs in families, but

this fact does not guarantee that individual family members will

develop the disease.

An increased incidence of rheumatoid arthritis occurs in families, but

this fact does not guarantee that individual family members will

develop the disease.

Q: My rheumatoid factor is negative. What does that mean?

A:

Although a positive rheumatoid factor is common, it is absent in 10–15%

of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. In such patients, the diagnosis

is made on the basis of the clinical examination.

Although a positive rheumatoid factor is common, it is absent in 10–15%

of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. In such patients, the diagnosis

is made on the basis of the clinical examination.