NONUNIONS AND MALUNIONS OF THE PELVIS

II – FRACTURES, DISLOCATIONS, NONUNIONS, AND MALUNIONS > Malunions

and Nonunions > CHAPTER 28 – NONUNIONS AND MALUNIONS OF THE PELVIS

because of the cancellous nature of the pelvis, nonunion is rare.

Nonetheless, nonunions can occur in the pelvis and have occasionally

been described in the literature (4). Factors

that may contribute to a pelvic nonunion include a delay in treatment,

inadequate immobilization of the fracture, an unstable fracture

pattern, high-energy trauma, and a large initial displacement of the

fracture.

instability of the posterior sacroiliac complex. This symptom, along

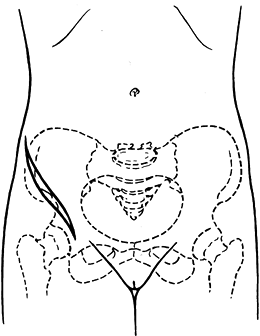

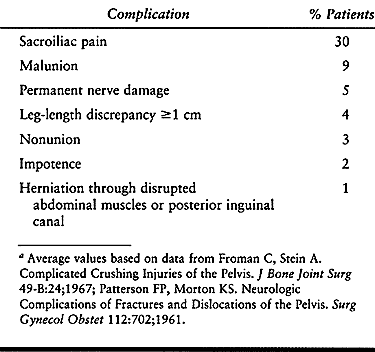

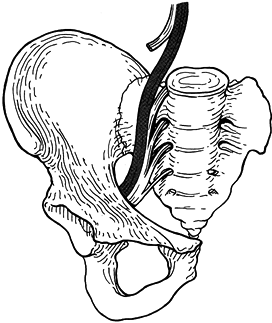

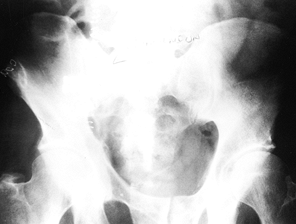

with others (Table 28.1), is most likely to occur following a very unstable, severely displaced, vertical shear fracture (Fig. 28.1). Fractures caused by lateral compression can also lead to posterior complex pain, however.

|

|

Table 28.1. Major Complications Following Pelvic Fracturesa

|

|

|

Figure 28.1. Very unstable vertical shear fracture of the pelvis.

|

with any fracture mechanism. The anteroposterior and lateral

compression types of injuries are the most commonly implicated in this

type of nonunion. The nonunion is usually in the symphysis or pubic

rami and may result in rotational instability of the pelvis with

anterior or posterior pain. Anterior pelvic nonunions are rarely

symptomatic and only occasionally require treatment.

documentation of the problem. Once you are convinced that a nonunion

exists, obtain plain radiographs with inlet and outlet views of the

pelvis. Judet views may be indicated, depending on the fracture pattern

(i.e., if there is an associated acetabular fracture). If further

diagnostic information is needed, a CT scan and possibly a technetium

bone scan may be helpful to confirm your suspicions. The technetium

scan will help distinguish an atrophic from a hypertrophic nonunion. If

your differential diagnosis does not exclude infection, do a CBC, a

differential, and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate along with a

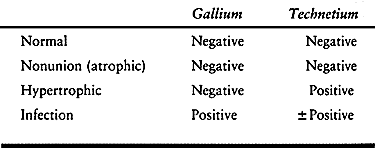

comparison of technetium and gallium scans (Table 28.2).

|

|

Table 28.2. Interpretation of Radionucleotide Scans

|

unrelieved by nonoperative treatment. Everything else is relative:

leg-length discrepancy, gait abnormality, permanent nerve-root damage,

or urinary disturbance. The area of pain must be accurately identified.

Posterior versus anterior and joint-related pain versus bony nonunion

must be clearly elucidated so that an appropriate treatment plan can be

developed.

nonunion is copious cancellous or corticocancellous bone grafting, with

or without rigid internal fixation. This is true with nonunions of the

pelvis, and these principles must be followed to obtain a successful

result. I feel that except for the rare occurrence of a painful

nonunion of a pubic ramus, bone grafting should be combined with rigid

internal fixation to provide stability and maintain anatomic reduction.

This approach allows direct access to the sacroiliac joint, permitting

bone grafting and fixation. In addition, because it is done in the

supine position, it allows better orientation and ease of access to the

pubis, if necessary. I consider the anterolateral incision to be the

utility approach to the pelvis because it permits access to the

sacroiliac joint, the iliac wing, and, by extension to the ilioinguinal

incision, the anterior column of the acetabula, pubic rami, and

symphysis. Thus, with the patient in the supine position, all areas of

the pelvis can be approached; this allows easier mobilization and

better orientation for final reduction.

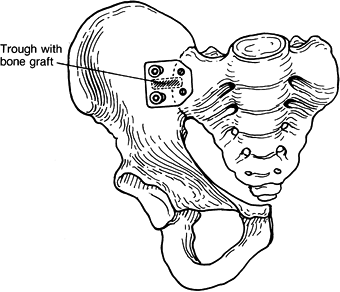

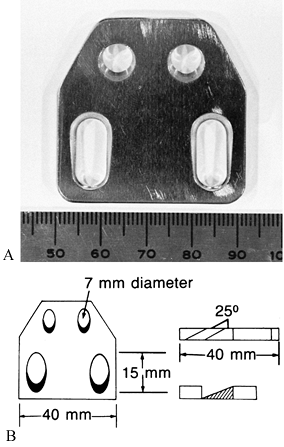

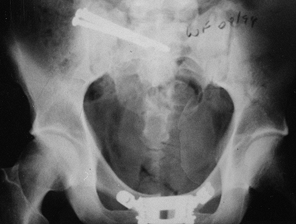

joint plate that we use to hold the reduced sacroiliac joint after

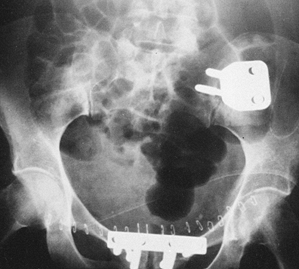

fresh pelvic fractures (Fig. 28.2) (14). We also use this plate to stabilize sacroiliac nonunions (Fig. 28.3, Fig. 28.4, Fig. 28.5, Fig. 28.6 and Fig. 28.7).

In laboratory tests using cadaver pelves, this plate provided equal or

greater fixation than other available devices, external or internal,

now used on the sacroiliac joint. When deformation to vertical and

rotational loads was measured, the external fixator proved to be the

weakest of all devices tested. Simpson et al. (29) have successfully

used two two-hole, 4.5-mm narrow dynamic compression plates for the

same purpose, but no biomechanical tests of this system have been

reported to date.

|

|

Figure 28.2. Anterior sacroiliac joint plate used to stabilize the sacroiliac joint.

|

|

|

Figure 28.3.

Anterior sacroiliac joint plate used to fuse the sacroiliac joint. The plate is available in a small size as well (20% smaller than the one shown). |

|

|

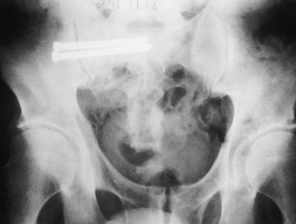

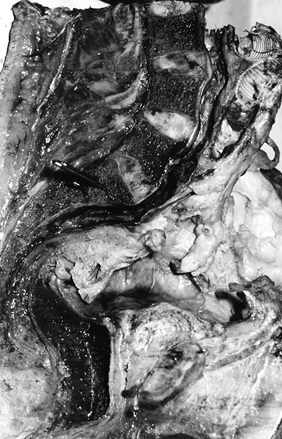

Figure 28.4.

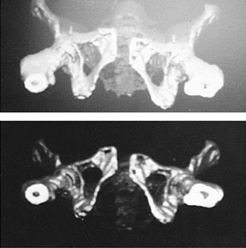

A 45-year-old woman with a very painful nonunion of the sacroiliac joint on the left plus symphyseal diastasis. Her initial fixation, months ago, was with an external fixator. Of note, she also had a nonunion of the tibia on the left and an L-5 nerve root deficit. |

|

|

Figure 28.5. Three-dimensional reconstructions from CT scans demonstrating the pathology present in Figure 28.4.

|

|

|

Figure 28.6. Three-dimensional reconstructions from X ray demonstrating the pathology in Figure 28.4.

|

|

|

Figure 28.7.

Fixation of the left sacroiliac joint with the Terray sacroiliac joint plate and fixation of the symphysis with one plate superiorly and a bone graft fixed anteriorly with two screws. The L-5 nerve root deficit improved dramatically immediately after surgery. |

-

Prepare and drape the area of the pelvis and ipsilateral leg. Drape the leg free as if doing a hip procedure.

-

Make a 15-cm incision along the iliac crest (Fig. 28.8).

Divide the subcutaneous tissue and, with cutting cautery, divide the

fascial attachment to the iliac crest. Locate the lateral cutaneous

nerve of the thigh and retract it medially.![]() Figure 28.8. Incision used for the anterolateral utility approach.

Figure 28.8. Incision used for the anterolateral utility approach. -

Using a Cobb periosteal elevator, perform a subperiosteal dissection along the iliac crest back to the sacroiliac joint (Fig. 28.9). Once the joint is reached, keep the hip

P.925

and knee flexed to allow relaxation of the femoral nerve and carry out a subperiosteal dissection over the sacral promontory. Figure 28.9.

Figure 28.9.

This view of the sacroiliac joint and right hemipelvis demonstrates the

course of the L-5 nerve root crossing the sacral promontory. -

Retract the L-5 nerve root anteromedially

using a narrow, pointed Hohmann retractor placed over the

anteroposterior aspects of the sacral promontory. -

Make a trough over the sacroiliac joint

in its central portion. Obtain a graft from the anterior portion of the

ipsilateral iliac wing and use it to fill the trough across the

sacroiliac joint. -

Place the sacroiliac joint plate over the

trough and secure it with 6.5-mm cancellous screws in the sacrum and

cortical screws in the iliac wing (Fig. 28.10). Use a flexible drill to make the holes.![]() Figure 28.10. Right hemipelvis with fusion of the sacroiliac joint showing the bone graft and plate placement.

Figure 28.10. Right hemipelvis with fusion of the sacroiliac joint showing the bone graft and plate placement. -

Direct the screws in the sacrum

posteromedially and those in the iliac wing into the posterosuperior

iliac spine. The plate is designed so that the two screws in the iliac

wing produce compression across the sacroiliac joint. Thus, instant

stability is achieved, usually with prompt reduction in the patient’s

pain. -

Irrigate the entire area copiously with

bacitracin and normal saline. Place a suction drain in the wound and

close it using #1 sutures in the deep fascia overlying the iliac crest,

2-0 in the subcutaneous tissue, and 3-0 or skin staples for skin

closure.

sacroiliac joint disruptions with associated iliac wing fractures or

those that cannot be reduced anatomically via a closed reduction.

the sacroiliac plate is fixation with iliosacral screws. These can be

inserted with the patient in the supine position through small stab

incisions laterally. Accurate placement of the screws is essential.

-

Do not place a sandbag under the iliac crest because this rotates the pelvis away from you.

-

Drape the ipsilateral leg free.

-

Use of the flexible drill and tap from the AO/ASIF acetabular reconstruction set is very helpful.

-

For plate fixation, use either the sacroiliac joint dynamic compression plate (Fig. 28.3) or two two- or three-hole, 4.5-mm narrow dynamic compression plates.

-

Check the patient pre- and postoperatively for L-5, S-1, or sacral plexus nerve-root deficit.

-

Place patient in the supine position on a radiolucent operating table.

-

Use fluoroscopy as a guide. The procedure

is based on the surface anatomic landmarks and good inlet and outlet

views to determine an accurate starting point on the iliac wing.

Position the imager to obtain a clear view of the sacral bodies. The

view from above the transverse plane is termed the “inlet” view, and

the anterior–posterior (AP) view is termed the “outlet” view. The

lateral view of the sacral bodies is important. Record the angle of the

inlet and outlet views on the imager for ease of repositioning. -

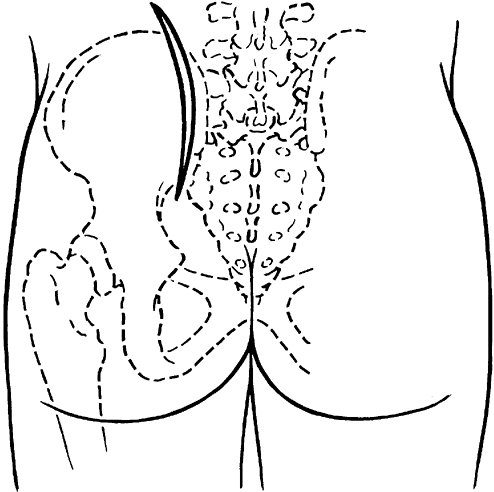

Identify landmarks on the pelvis to help

find the insertion point of the guide wire. This is done by drawing a

vertical line on the skin of the patient beginning at the anterior

superior iliac spine (ASIS) and extending posteriorly toward the

operating table. Draw a second horizontal line beginning at the

posterior edge of the trochanter. These lines intersect to create a

cross. The center of this cross represents the entry point of the guide

wire seen in Fig. 28.11. A line should also be

drawn to indicate the projections of the inlet and outlet image. These

may also intersect to create a small triangle to again help determine

the entry point of the guide wire, as seen in Figure 28.11.

The main importance of these two lines, however, is to indicate the

planes of adjustment of the pin on the inlet view and outlet view so

that its track can be adjusted easily to avoid a malposition of the

screw. Figure 28.11.

Figure 28.11.

Anatomic landmarks on the pelvis of a patient to help find the

insertion point of the guide wire. (Note: The head of the patient is on

the left, and the foot of the patient is on the right.) -

Incise the skin with a #15 blade.

-

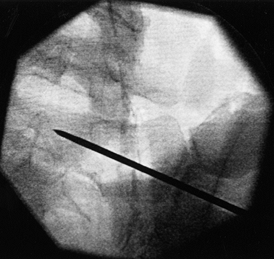

Position the guide wire relative to the spinal canal and the sacral promontory as seen on the inlet view (Fig. 28.12). The outlet view shows the pin’s position relative to the S-1 and S-2 foramina (Fig. 28.13).

Aim the guide wire to approach the sacral body in a

posterior-to-anterior direction from caudad to cephalad. As the guide

wire is advanced, check it frequently in both the inlet and outlet

views. The pin should cross the midline.![]() Figure 28.12. Inlet view of the pelvis, showing the guide wire central to the spinal canal and sacral promontory.

Figure 28.12. Inlet view of the pelvis, showing the guide wire central to the spinal canal and sacral promontory. Figure 28.13. Outlet view of the pelvis, showing the guide wire’s relative position to the S-1 foramina with the pin in the midbody of S-1.

Figure 28.13. Outlet view of the pelvis, showing the guide wire’s relative position to the S-1 foramina with the pin in the midbody of S-1. -

Once the pins are in place, measure for

screw depth and drill the iliac cortex and SI joint. Do not overdrill

the full length of the guide wire to avoid pin pullout. -

Then insert self-tapping screws over the guide wire. See Chapter 17 for a somewhat different approach to this same fixation.

for sacral nonunions, as these cannot be approached safely through the

anterior approach, and it is useful for malunions as well (Fig. 28.15). Sacral malunions or nonunions are an absolute contraindication for the anterior SI joint plate.

|

|

Figure 28.15. Computed tomographic scan illustrating nonunion of the right sacral alae.

|

-

It may be used to treat fresh sacroiliac joint disruptions as well as nonunions and is preferred by some authors (5,6,12).

-

Place the patient in the prone position (Fig. 28.16).

Figure 28.16. Incision used for posterior approach to the sacroiliac joint.

Figure 28.16. Incision used for posterior approach to the sacroiliac joint.

-

Use a full radiolucent table such as an OSI table.

-

Start the guide pins low in the iliac

wing area and aim caudad to cephalad and posterior to anterior to avoid

a wire that partially exits the anterior cortex and can injure the L-5

nerve root. -

Do not tip the patient but raise the patient off the bed using a pad under the sacrum.

-

Do not accept a screw position close to

the foramina or sacral canal. The screws must be in “ideal” position.

They must be dead center on the inlet and outlet view. If they are

“close” to the canal or foramina, there is a 30% chance that they are

malpositioned (12). The S-1 pedicle has adequate cross-sectional area for two to three 7.0-mm screws (Fig. 28.14).

|

|

Figure 28.14. Iliosacral screws in the midbody of S-1.

|

-

Use an image intensifier to establish the

orientation of the anterior sacral foramina on the outlet view and the

spinal canal and sacral promontory on the inlet view.

visibility of the sacroiliac joint. It is difficult to obtain an

accurate reduction, and extraarticular fusion is usually necessary, as

opposed to an intraarticular fusion. Nerve root damage can occur from

inaccurate placement of screws and is always of concern. However,

careful technique and placement of screws in the “ideal” position, not

close to the foramina or to the spinal canal, makes the chance of nerve

injury slight (12).

-

Identify the nonunion and curet the lesion out to allow for bone grafting.

-

Insert a cancellous iliac bone graft after achieving adequate

P.928

reduction (Fig. 28.17).

Obtain the bone graft from the ipsilateral iliac crest, slightly

anterior to the operative site, and through a separate incision.

Perform an extra-articular fusion between the posterior spine of the

ilium and the posterior sacrum by creating a trough and laying in a

cancellous and cortical-cancellous graft. No fixation is used over the

graft. Figure 28.17.

Figure 28.17.

The initial postoperative film after bone grafting and fixation of the

sacral nonunion with iliosacral screws via the posterior approach. -

Position the screws as for the anterior

approach with iliosacral screw fixation. The inlet and outlet views

are, of course, reversed, as the patient is in the prone position.

Again, caudad-to-cephalad and posterior-to-anterior positioning of the

screws is essential to prevent injury to the L-5 nerve root. The case

in Fig. 28.17 and Fig. 28.18 shows good fixation and healing of the sacral nonunion, and the patient was without pain 6 months after the repair.![]() Figure 28.18. Six-month follow-up of the patient with a united sacral nonunion (pain-free with excellent mobility).

Figure 28.18. Six-month follow-up of the patient with a united sacral nonunion (pain-free with excellent mobility).

-

Use a radiolucent back frame and a full radiolucent table, such as an OSI fracture table.

-

Insert the screws to the midbody of S-1 or beyond in order to achieve adequate fixation.

-

Make the skin incision laterally. Reflect

the gluteus maximus off the spinous process so that its blood supply is

not disturbed; this is needed for good healing. -

Use short-threaded screws if sacral malunions or nonunions are being treated.

-

Insert the screws through a percutaneous

stab incision laterally rather than through the surgical wound, as this

requires more reflection of the soft tissues than desirable. -

Use guide wires for the cannulated

screws, which should be at least 3.0 to 3.2 mm in diameter to avoid

bending, which affects accuracy of placement. -

Use self-tapping screws.

-

Irrigate the entire area copiously with bacitracin in normal saline.

-

Reattach the gluteus maximus medially.

Place a suction drain in the wound and bring it out laterally.

Reapproximate the subcutaneous tissue and skin.

both the anterolateral and posterior methods give fixation that will

approach about 50% of the normal strength of the pelvis. Therefore, it

is possible to allow the patient to ambulate with crutches after the

drain is removed at 48 h. Permit touch-down weightbearing for 6 weeks

and partial weightbearing for a further 6 weeks. Full weightbearing is

allowed once radiologic union is achieved at 10 to 12 weeks.

gross disruption of the pelvis, is rarely symptomatic. If the pelvis is

rotationally unstable because of symphyseal nonunion, however, it may

require treatment to relieve pain or bladder irritability. The only

absolute indication for operative intervention is pain unrelieved by

nonoperative measures. Anterior nonunions are not as common as those in

the posterior portion of the pelvic ring but can be just as

debilitating. The patient may complain of pain,

clicking of the symphysis on ambulation, urinary problems, or clitoral irritation.

pyelogram, cystogram, and urethrogram to identify bladder or urethral

impingement. A cystometrogram may be indicated if urinary complaints

are the main symptoms. The approach to the problem, once identified,

must be individualized to the patient and the site of nonunion.

Terray Manufacture, Arenprior, Ontario; in conjunction with Zimmer USA)

or a six-hole 3.5-mm pelvic reconstruction plate for fusion of the

pubic symphysis (Fig. 28.19). In biomechanical studies done by Tile et al. (32; personal communication, 1984) and Leighton et al. (14),

the symphyseal plate provided greater stability of the anterior pelvic

ring, followed closely by the application of two plates. The single

plate, although clinically successful, provided the least stability in

biomechanical studies.

|

|

Figure 28.19. Pelvis with symphyseal plate and bone graft to treat symphyseal nonunion.

|

an onlay autologous bone graft. A nonunion in the pubic rami usually is

atrophic, so a bone graft and internal fixation is required.

-

Insert an indwelling Foley catheter before surgery to help identify the urethra and bladder.

-

About 3 to 4 cm above the pubis, make a transverse skin incision 8 to 10 cm long.

-

Divide subcutaneous tissue and identify

the rectus abdominis muscle. Make a vertical midline incision through

the rectus abdominis fascia; identify the two heads. Separate them in

the midline and reflect laterally, taking care to protect the spermatic

cord or round ligament. -

Once the rectus is reflected as much as

needed, the symphysis is readily seen. Expose the symphysis and pubic

rami with subperiosteal dissection to either side for a total of 10 to

12 cm. Make the exposure both superiorly and anteriorly along the

superior pubic ramus. -

Once the body of each pubic ramus can be identified, dissect the bladder free of the symphysis.

-

Place a retractor posterior to the symphysis to protect the bladder and urethra and remove the fibrous mass from the symphysis.

-

Place a pointed reduction forceps in each obturator foramen and reduce the symphysis.

-

An alternative to this technique is to

use the pubic tubercles as a purchase point for the pointed clamps.

This works best when a six-hole reconstruction plate is used. -

Once reduction is achieved, place the

special symphyseal six-hole plate for a trial fit. It may be necessary

to rongeur the pubic tubercles down slightly to obtain a flat surface.

Bend the four tabs of the plate as necessary to achieve a close fit. Be

certain that the lateral holes are sitting on the bone. There is a

tendency for plates on the symphysis to shift anteriorly off the pubic

rami. -

To place screws, drill through the two

holes in the plate closest to the symphysis first. Palpate the

posterior aspect of the symphysis to be certain that the drill points

remain in the bone until they exit the lower border of the inferior

pubic rami. -

Use fully threaded cancellous screws, which are usually 40 to 60 mm in length.

-

Then drill the lateral holes to accept 4.5-mm cortical screws. Use cancellous screws if the bone quality is poor.

-

Now place screws in the anterior holes of

the plate while protecting the bladder with a retractor. Use cortical

screws (3.5 mm with 4.5-mm washers or 4.5-mm screws; 4.5-mm washers are

available from Zimmer USA) the average length of which is approximately

20 to 24 mm. If the quality of the bone is poor, use cancellous screws. -

Close the rectus muscle and fascia snugly. Place a drain behind the symphysis.

-

Place the patient on bed rest for 24 h and then mobilize to a chair.

-

Remove the suction drain at 48 h.

-

At the same time, ambulate with crutches, allowing touch-down only on the more unstable side.

-

Catheterize the patient so the urethra can be easily located.

-

Always protect the posterior structures when drilling and tapping.

-

A six-hole 3.5-mm reconstruction plate may be used, depending on the reduction obtained and stability required.

small percentage of these nonunions require surgical treatment.

Consequently, no one has a great deal of experience in dealing with

this problem. Be certain that this is the cause of the patient’s pain

before undertaking surgery. The treatment requires autologous bone

graft, with or without internal fixation, depending on the type of

nonunion (i.e., atrophic versus hypertrophic) and bone quality.

-

To expose the superior pubic ramus, use the ilioinguinal approach described in Chapter 2. Protect the contents of the inguinal canal.

-

Debride both ends of the nonunion and

clear them of any fibrous tissue. Open the intramedullary canal on each

side. Petal the cortical bone for 2 to 3 cm on each side of the

nonunion using a small osteotome and a powered burr. -

Place cancellous bone graft around the

site of nonunion in a barrel-stave fashion. Plate the ramus if

additional stability is needed. -

Close the wound over a suction drain in the usual manner.

nonunion. This is usually an atrophic nonunion at the junction of the

ramus with the ischial tuberosity. The patient has pain on sitting.

-

Place the patient in the lithotomy position. In this position, the ischium is very easy to palpate.

-

Incise directly down to the ischion and

inferior pubic ramus. Take care to avoid the pudendal vessels, which

exit anteromedially. Occasionally, the nonunion site may be more

proximal, near the posterior column of the acetabulum. If this is the

case, then use the standard Kocher-Langenbeck approach, as described in

Chapter 3.

-

If a small superior fragment is present, excise it.

-

Use flexible drills and taps.

-

Freshen the bone ends at the nonunion site and add copious autologous bone graft.

-

Internal fixation is usually not

required; however, a 3.5-mm reconstruction plate can be applied. Keep

the patient touch-down weightbearing with crutches until radiographic

union is achieved; this usually takes 8 to 14 weeks. -

If both the inferior and superior rami

are involved, however, then plate the superior ramus with at least four

cortices of fixation on either side of the fracture site. I also add an

anterior external frame to increase stability.

-

Use the anterolateral approach to the sacroiliac joint: it allows good visualization of the entire iliac wing.

-

Identify the site of the nonunion. If the

ununited fragment is small, then excise it. If it is a large fragment

or involves the whole ileum, then use the methods described above for

treating the nonunion. -

Expose the bone ends, freshen them, and achieve an anatomic reduction.

-

Then place a lag screw from the anterior

iliac crest across the fracture site and into the body of the ilium.

Augment this with a wide 4.5-mm dynamic compression plate, fixing at

least four cortices on either side of the fracture site. -

Apply an onlay bone graft. Close the wound in layers over a suction drain.

using crutches, with touch-down weightbearing on the affected side.

Continue to protect the ilium until clinical or radiologic union is

observed at 8 to 12 weeks.

nonunions; however, little is available in the literature regarding

these challenging problems. Slatis and Huittinen (30), in their review of 65 vertical shear fractures treated closed without internal or external fixation, noted a 46%

incidence of late sequelae. These included pain from a malreduced

posterior sacroiliac complex, limb-length discrepancy and gait

abnormalities, urinary symptoms, and permanent nerve damage (Table 28.1).

Bucholz has described the displacement of vertical shear fractures as

being posterior, cephalad, and externally rotated, leading to a very

prominent posterior superior iliac spine (2).

malunion. A lateral compression injury usually results in an internal

rotational deformity, which can lead to a major leg-length discrepancy

and impingement of the rami on the bladder or perineum. In one variant

of the lateral compression fracture, the pubic rami and the pubic body

distal to the fracture are spun into a vertical position, which can

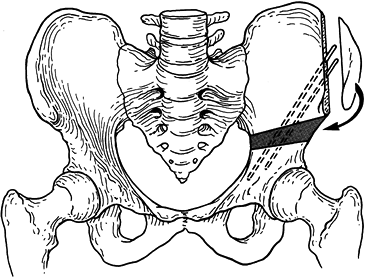

cause impingement on the perineum and cause dyspareunia (Fig. 28.20).

The anterolateral compression injury or “open book” fracture can heal

in a widely displaced position, but this is rarely symptomatic. Iliac

wing fractures, if left untreated, can heal in a malrotated or

shortened position, but these malunions are not symptomatic.

|

|

Figure 28.20.

Variant of a lateral compression injury with perineal impingement. If symptomatic, this may require reduction and fixation with symphyseal plates. |

pelvic malunion because it is the most unstable fracture and,

therefore, the most difficult to maintain in a reduced position. For

that reason solid fixation of the pelvic ring both posteriorly and

anteriorly is recommended. Permanent nerve damage is present in a

surprising number of pelvic fractures (5%) (13).

L-5 and S-1 are the roots most commonly involved, but the sacral plexus

can also be injured. It is important to document any problems and

discuss them with the patient, because surgery will generally not

improve a nerve palsy or causalgia.

nonoperative treatment. Many of these patients are involved in workers

compensation or legal conflicts. It may be wise, therefore, to wait

until these conflicts are resolved before undertaking surgery, as the

indications are usually based on subjective symptoms and the outcomes

are not very predictable. In my experience, most of these patients, if

given time, can return to their normal daily activities without

surgical intervention. A strong relative indication for surgery is a

leg-length discrepancy of 2 cm or more.

cause problems and is the most difficult to correct. Direct fusion of

the area (see the discussion in Nonunions, above) is the mainstay of

treatment, although reduction of any coexisting malunion or malposition

is indicated also. Late reduction of a malpositioned sacroiliac joint

is very difficult, however.

mobilization of the anterior pelvic complex to readjust the position of

the entire hemipelvis, which is why this type of surgery is so

difficult and rarely indicated. This surgery is fraught with

complications, and the results cannot be predicted reliably. If surgery

is indicated, however, I recommend an anterior–lateral approach that

must be individualized to the original fracture pattern. Most other

authors have recommended a posterior approach, and certainly this can

be used (5,6,12,13). A combined anterior and posterior approach is often required. Recently, the anterolateral approach has become popular (3,7,10).

-

If the original disruption occurred at the symphysis, use a Pfannenstiel incision to mobilize this area.

-

When the deformity is in the pubic rami,

individual osteotomies must be done through separate incisions.

Approach the superior pubic ramus through an inguinal incision and

inferior pubic ramus in the lithotomy position, as described above. -

Once the anterior pelvis has been

mobilized, make an anterolateral utility incision to mobilize the

posterior sacroiliac complex. Expose the ilium and the sacroiliac joint. -

Place small Kirschner wires parallel to

each other in the sacrum and ilium in such a way that they will end up

in the same plane once reduction has been achieved. These pins also

serve as a guide to internal and external rotation of the pelvis. -

Use an osteotome and sharp dissection to

mobilize the sacroiliac joint if required. It is extremely difficult to

mobilize the hemipelvis. Much soft-tissue release is required along the

inside and outside of the iliac wing. -

Once the hemipelvis is mobilized, place a

clamp on the iliac wing to aid in its manipulation. Externally rotate

the leg and apply traction. Reduce the pelvis, internally rotate the

leg, and drive a wide staple across the sacroiliac joint along its

posterosuperior edge. -

Place a bone graft across the joint as discussed above for nonunion.

-

Apply the sacroiliac plate, using dynamic

compression plating. I have found this method of fusing the sacroiliac

joint to be successful, as have Rand (22), Tile (32), and Simpson et al. (29), but the total number of cases is small. -

Next check the alignment of the symphysis

and the rami if they were involved. Be certain that the rotational

alignment in the anteroposterior plane is correct. Posteriorly, this

rotational alignment is most difficult to determine, and it is at this

point that the advantages of the anterolateral utility incision are

realized. -

Once reduction is achieved, apply the symphyseal plate along with bone graft.

-

If independent osteotomies were used on

the pubic rami, then use an anterior external fixator or internal

fixation to stabilize the anterior pelvis. -

Close all wounds over suction drains in the usual fashion.

-

As stated earlier, a combination of a

posterior approach to the sacroiliac joint plus a Pfannenstiel incision

can be used to accomplish the same result.

movement only from bed to chair for 2 to 3 weeks. Allow crutch walking

at 3 weeks with touch-down weightbearing on the unstable side,

continuing until union is achieved at about 12 to 16 weeks.

This usually is secondary to an anteroposterior (open book) fracture,

which is rarely symptomatic. If it is believed to be the cause of the

patient’s discomfort, treatment is the same as for a nonunion of the

symphysis.

the pelvis with the hemipelvis internally rotated and the symphysis

healed in an overlapped position. If union has occurred, the anterior

complex is rarely the cause of the problems. However, the real problem

anteriorly is the variant of a lateral compression injury mentioned

earlier in which the pubic rami fragments are rotated in the frontal

plane (Fig. 28.20). If these structures impinge

on the perineum and cause dyspareunia, treat the malunion either by

excision, if the fragment is small, or by reduction and internal

fixation.

-

Use an ilioinguinal approach plus a separate incision to osteotomize the inferior pubic ramus.

-

Place patient in the lithotomy position. Expose and osteotomize the inferior pubic ramus first.

-

Then make an ilioinguinal incision and expose the superior pubic ramus and the symphysis.

-

Mobilize the fragment. If it is small, excise it; otherwise, fix it with a symphyseal plate.

-

Mobilize the patient with crutches, touch-down weightbearing on the affected side, for 4 to 6 weeks.

is leg-length inequality. I feel that if the discrepancy is 2 cm or

more, then surgical intervention is justified. If the pelvis is not too

deformed, and the patient is relatively young, I do a modified Salter

osteotomy. With an older patient, or one who has a deformed pelvis but

no real pain, a leg-lengthening or leg-shortening procedure is the

treatment of choice. The shorter in stature the patient is, the more I

would favor a lengthening procedure. Leg-length films are needed to

document the true leg-length discrepancy. The leg length must be

measured on these films from the anterosuperior iliac spine to the

ankle, not from the acetabulum to the ankle as in standard leg-length

films. Remember, the loss of height is within the pelvis and not in the

femur or tibia.

In this way, the posterior aspect of the pelvic brim is opened, thus

gaining length in the shortened extremity. This usually will allow an

increase of 2 to 2.5 cm in leg length. By externally rotating the

distal fragment, the osteotomy will allow correction of an internal

rotation of the pelvis and permit the leg to assume its normal position.

|

|

Figure 28.21. Modified Salter innominate osteotomy. Note that the block of bone actually opens the posterior cortex.

|

the symptoms are attributed to pressure on the bladder secondary to

pelvic deformity, then surgery may be helpful. An adequate preoperative

workup must be done, including radiographic contrast studies and

possibly a cystometrogram. If surgery is to be performed, make sure a

catheter is inserted before the operative procedure. With a urologist’s

help, use a direct approach to the pubis through a Pfannenstiel

incision and remove the excess bone to take the pressure off the

bladder. An osteotomy of the pelvis to correct the deformity is rarely

indicated for urinary symptoms alone. Nonunion at the symphysis can

cause urinary symptoms with or without discomfort. The treatment in

this case is symphyseal-plate fixation with bone grafting of the

symphysis, as described above in the section on nonunions.

pelvis is rare, and, therefore, there are few large series documenting

results of treatment. Pennal and Massiah (20)

have the largest series and report good results using the posterior

approach to the sacroiliac joint. Their series consisted of 42 patients

with nonunion and delayed union, 39 men and 3 women, with an average

age of 35 years. Of the patients, 24 were treated nonoperatively and 18

by surgery. The surgery was aimed at stabilizing the nonunion and

supplemental bone grafting. The operative group did better than the

nonoperative group as far as returning to preinjury jobs and

activities, and a solid union was achieved in 15 of the 18 treated with

surgery.

reported good results in all seven patients who underwent a direct

approach to the malunion site. However, despite their expertise in

surgery, the average operating time in these patients was 6 h, and the

average blood loss was 1,200 mL.

anatomic reduction as early as practical. Late reduction and fusion are

definitely much more difficult and hazardous. Fortuitously, since the

mid-1990s, many companies have developed superior plate reduction

clamps and pushers in order to allow for better and easier anatomic

alignment of acute fractures. With the use of these advanced tools, and

more rigid internal fixation, such as the iliosacral screws and

symphyseal plates, anatomic reduction can be achieved and maintained

while the pelvic ring heals. Although these techniques do not allow for

perfect reduction in every case, they do allow for a very acceptable

reduction in most patients. As stated earlier, it is very important

that the source of the pain be identified as accurately as possible

before any type of posttraumatic reconstruction is undertaken, as pain,

particularly posterior pelvic and back pain, can have many origins

other than from the bony pelvic ring.

scheme: *, classic article; #, review article; !, basic research

article; and +, clinical results/outcome study.

HH, Pattee GA, McAfee P. Compression of a Sacral Nerve as a

Complication of Screw Fixation of the Sacroiliac Joint: A Case Report. J Bone Joint Surg 1986;68-A:679.

C, Smyth B, Petrie D, Leighton R. A New Symphyseal Plate. Biochemical

Study Presented at the Canadian Orthopaedic Association Meeting in June

1995 and updated at the Canadian Orthopaedic Association Meeting in

June 1998.

F, Egbers HJ, Havermann D, Zimmerman M. Results Following the

Conservative and Surgically Treated Injuries of the Pelvic Ring within

the Scope of a Prospective Study. Unfallchirurgerie 1995;98:355.

PJ, Van-Allen M, Bray TJ, Nelson D. Computed Tomography-Guided Fixation

of the Unstable Posterior Pelvic Ring disruptions. J Orthop Trauma 1992;6:420.

NA, Coombs R, Jackson WT, Rusin JJ. Percutaneous Computed

Tomography-Guided Stabilization of the Posterior Pelvic Fractures. Can J Surg 1990;33:492.

NA, Coombs R, Rusin JJ, et al. Percutaneous CT-Guided Stabilization of

Complex Sacroiliac Joint Disruption with Threaded Compression Bars. Orthopaedics 1992;15:1427.

GS, Leit ME, Gruen RJ. Functional Outcome of Patients with Unstable

Pelvic Ring Fractures Stabilized with Open Reduction and Internal

Fixation. J Trauma 1995;39:838.

P, Logan M, Petrie D, et al. Percutaneous Iliosacral Screw Fixation—Is

It Safe? Paper Presented at the Canadian Orthopaedic Association, June

1997, and at the Orthopaedic Trauma Association, October 1998.

RK. Biomechanical Study of Vertical Shear Fractures of the Pelvis.

Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Academy of

Orthopaedic Surgeons, San Francisco, 1997.

AC, Rorabec CH, Halpenny J. Long-Term Pain and Disability in Relation

to Residual Deformity after Displaced Pelvic Ring Fractures. Can J Surg 1990;33:492.

MLC, Kregor PJ, Mayo K. 103 Spine Percutaneous Iliosacral Screws for

Fixation of the Disrupted Posterior Pelvic Ring after Indirect

Reduction. Indications, Techniques, Errors and Results. Paper presented

at the Orthopaedic Trauma Association Annual Meeting, Minneapolis,

October, 1992.

HE, Nelson DD, Mears DC. Reconstructive Surgery of the Pelvis. Paper

presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic

Surgeon, New Orleans, 1982.

JA, Mino DE, Werner FW, Murray DG. Posterior Stabilization of Pelvic

Fractures by Use of Threaded Compression Rods. Case Report and

Mechanical Testing. Clin Orthop 1985;192:240.

TE, Boone DC, Gruen GS, Peitzmann AB; Percutaneous Iliosacral Screw

Fixation; Early Treatment for Unstable Posterior Pelvic RINg

disruptions. J Trauma 1995;38:453.

P, Craninx L, Rommens P, Broos P. Functional results following the

surgical treatment of unstable pelvic girdle fractures. Acta Chir Belg 1991;91:250.