Monteggia Fracture

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Monteggia Fracture

Monteggia Fracture

Paul D. Sponseller MD

Simon C. Mears MD, PhD

Description

-

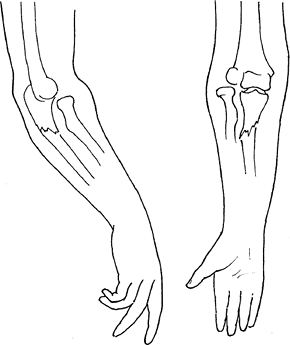

Because the radius and ulna are bound by

ligaments and an interosseous membrane, a displaced fracture of the

ulna often is accompanied by dislocation of the radial head, a

combination termed a Monteggia fracture (Fig. 1). -

The diagnosis sometimes is missed because the dislocation can be overlooked.

-

Reduction of both the fracture and the dislocation must be achieved.

-

Bado (1) classification:

-

Most commonly used system

-

Based on the direction of the dislocation

of the radial head, which is the same as the direction of the apex of

the ulnar fracture -

4 types:

-

I: Anterior dislocation of the radial head (most common type)

-

II: Posterior dislocation of the radial head

-

III: Lateral dislocation of the radial head (2nd most common pattern in childhood)

-

IV: Anterior dislocation of the radial head in combination with a proximal radial fracture

Fig.

Fig.

1. An angulated, isolated ulna fracture causes the radial head to

dislocate. This combination is called a Monteggia fracture.

-

-

Epidemiology

Fracture occurrence is distributed evenly between males and females (2).

Incidence

-

Relatively uncommon

-

Peak incidence: Ages 4–10 years (3)

-

However, this fracture may occur at any age, including adulthood.

Prevalence

-

Most common in children: Bado type-I fractures, with plastic deformation of the ulna (4).

-

Most common in adults: Bado type I and type II fractures (5)

Risk Factors

Any child or adult with a fracture of the proximal or middle of the ulnar shaft should be considered at risk for this fracture.

Etiology

-

The ligamentous connections between the

radius and ulna cause the radial head dislocation to occur when the

ulna fractures, or vice versa. -

Type I fracture mechanism: Hyperpronation or hyperextension

-

Type II fracture mechanism: Axial loading of a partially flexed elbow

Signs and Symptoms

-

Signs:

-

Swelling in the forearm and elbow

-

In cases diagnosed late, a bump may be

present over the elbow at the time a cast is removed for treatment of

an ulnar fracture, indicating the dislocated radial head.

-

-

Symptoms:

-

Acutely, tenderness over the elbow and deformity

-

If diagnosed late, the unreduced radial

head could block the full range of flexion or extension or cause

clicking with pronation and supination.

-

Physical Exam

-

In acute cases, diagnosis should be made

primarily by radiography showing both the ulnar fracture and the radial

head dislocation. -

In chronic cases, a prominence of the radial head is visible when the arm is out of the cast.

-

This prominence represents the dislocated radial head and may be compared with the opposite side.

-

Tests

Imaging

-

Radiography:

-

Plain radiographs are sufficient for diagnosis.

-

All forearm fractures should include visualization of the elbow and wrist joints.

-

These radiographs should be true AP and lateral views.

-

If they cannot be obtained on the same film, separate films of these regions should be ordered.

-

The physician should be available to help in positioning, if needed.

-

-

-

MRI is not required for diagnosis.

Pathological Findings

-

At the time of injury, the annular ligament of the radius is torn and becomes infolded.

-

If the radial head remains unreduced for several years, it degenerates because the cartilage wears away.

Differential Diagnosis

-

An isolated ulnar fracture may occur without radial head dislocation.

-

The status of the radial head may be determined by drawing a line on the radiograph through the radial shaft.

-

This line should fall in the center of the capitellum of the distal humerus.

-

-

An isolated radial head dislocation may occur, but it is rare.

-

Congenital dislocation of the radial head does occur.

-

May be distinguished by changes in the

shape of the radial head: Overgrowth and loss of the normal concave

reciprocal articular surface

-

P.263

General Measures

-

For children, closed reduction usually is successful for treating both the dislocated radial head and the ulnar fracture.

-

The mechanism used to reduce the ulnar fracture also is used to maintain reduction of the radial head fracture.

-

Type I fractures: The forearm should be in supination to midposition, and the elbow should be in flexion of >110°.

-

Type II fractures: The elbow should be in extension.

-

-

In both type I and type II fractures, the radial head may require a push to place it properly.

-

An above-the-elbow cast should be applied, and a bivalved cast should be used if substantial swelling is present.

-

A radiograph should be obtained after reduction to confirm that alignment is satisfactory.

-

Unstable or displaced fractures after reduction:

-

In children: Require open reduction and fixation

-

In adults: Require open reduction and internal fixation

-

-

Follow-up in 1 week

-

Late detection of a Monteggia fracture:

-

1–3 weeks after injury, the radial head may require open reduction, even in children.

-

>3 weeks after injury, reconstruction of the annular ligament of the radial head may be necessary.

-

Special Therapy

Physical Therapy

-

Adults often need therapy to regain optimal motion.

-

In children, physical therapy is not needed because parents can do the necessary exercises with them.

Surgery

-

If the ulnar fracture cannot be

maintained or reduced, open reduction and internal fixation should be

performed, which usually causes the radial head to become and remain

reduced. -

If it is not reduced, then an open reduction of the radial head should be performed.

-

In a child, internal fixation of the ulna may be done with an intramedullary nail if closed reduction has failed.

-

In adults, a Monteggia fracture should be

treated directly with open reduction and internal fixation (rigid plate

and screws) of the ulna.-

Radial head reduction only if needed

-

-

Late reconstruction of the annular ligament of the ulna is done using the Bell-Tawse technique (6).

-

A strip of triceps fascia is used to reconstruct the ligament and is anchored to the ulna.

-

-

In children, immobilization is continued for 6 weeks.

-

In adults, because of a greater risk of stiffness, carefully supervised ROM may be started earlier.

Disposition

Issues for Referral

Monteggia fractures should be referred to an orthopaedic surgeon promptly to ensure timely and adequate reduction.

Prognosis

-

With careful reduction and follow-up, the prognosis is good (3).

-

Stable injuries in children have an excellent prognosis with closed treatment.

-

Bado type I injuries are thought to have a worse prognosis (7).

-

Injuries that are associated with coronoid or radial head fracture also have poorer outcomes (2).

-

Patients with missed injuries have a poorer prognosis.

-

Results of late reconstruction are unpredictable (8).

Complications

-

Redislocation

-

Stiffness

-

Proximal radioulnar synostosis

-

Elbow instability

-

Nerve injury (usually radial) at time of radial head dislocation (9)

Patient Monitoring

-

The patient should be seen 1 week after injury to rule out redisplacement.

-

Additional follow-up should be continued until ROM is satisfactory.

References

1. Bado JL. The Monteggia lesion. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1967;50:71–86.

2. Ring D, Jupiter JB, Simpson NS. Monteggia fractures in adults. J Bone Joint Surg 1998;80A: 1733–1744.

3. Wiley JJ, Galey JP. Monteggia injuries in children. J Bone Joint Surg 1985;67B:728–731.

4. Ring D, Jupiter JB, Waters PM. Monteggia fractures in children and adults. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1998;6:215–224.

5. Llusa Perez M, Lamas C, Martinez I, et al. Monteggia fractures in adults. Review of 54 cases. Chir Main 2002;21:293–297.

6. Bell Tawse AJS. The treatment of malunited anterior Monteggia fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg 1965;47B:718–723.

7. Givon U, Pritsch M, Levy O, et al. Monteggia and equivalent lesions. A study of 41 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1997;337:208–215.

8. David-West KS, Wilson NIL, Sherlock DA, et al. Missed Monteggia injuries. Injury 2005;36: 1206–1209.

9. Ristic S, Strauch RJ, Rosenwasser MP. The assessment and treatment of nerve dysfunction after trauma around the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000;370:138–153.

Codes

ICD9-CM

-

813.03 Closed Monteggia fracture

-

813.13 Open Monteggia fracture

Patient Teaching

-

At the time of initial consultation, patients should be counseled about the risk of redislocation.

-

Such counseling helps encourage compliance with follow-up care and exercises.

FAQ

Q: What is the prognosis of a Monteggia fracture in a child?

A:

The prognosis of stable fractures treated without surgery is excellent.

Missed fractures that are displaced have a much poorer outcome.

The prognosis of stable fractures treated without surgery is excellent.

Missed fractures that are displaced have a much poorer outcome.