INFECTIONS OF THE HAND

Professor of Orthopaedics, Professor of Surgery, Division of Plastic

Surgery; Chief, Hand and Upper Extremity Service, School of Medicine,

University of California, Davis, Sacramento, California, 95817.

Because loss of hand function follows an inadequately treated

infection, make every effort to achieve complete and expedient

resolution. In our experience treatment requires aggressive debridement

when surgery is indicated, use of antimicrobials that cover the full

spectrum of infecting agents known to be present in hand infections,

and appropriate follow-up care.

skin barrier and inoculation of the tissues. Tissue necrosis and

impairment of circulation create an ideal environment for bacteria to

flourish. Bacterial proliferation produces the initial signs of

infection: erythema, calor, swelling, and tenderness. The local tissue

reaction causes edema and further impairment of local circulation, with

eventual abscess formation. The venous drainage of the hand (palmar to

dorsal) and the fact that the skin is less

tethered

on the dorsum explain the preponderance of dorsal swelling in hand

infections. Infection must be differentiated from noninfectious

conditions such as gout, collagen vascular disease, inflammatory

tenosynovitis, acute soft-tissue calcification, foreign-body reaction,

and more rarely, neoplastic processes.

proliferation and remove purulent and necrotic tissue while leaving

behind the well-vascularized and viable tissue (5,18,30).

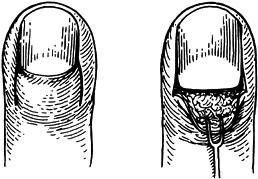

Whereas cellulitis is treated with antibiotics without surgery, once an

abscess has become evident, surgical drainage is necessary (Fig. 73.1).

Excise the abscess cavity, its walls, loculations, and all infected

tissue as well. Thorough debridement improves blood supply, enabling

natural humoral and cellular antibacterial factors and antibiotics to

enter the infected area. Leave wounds open to allow drainage, except in

larger joints (the wrist and proximally), in which closed-suction

drainage may be used. After surgery, keep the hand initially

immobilized and elevated.

Once

the wound is nontender, nonerythematous, and not indurated, encourage

active motion to prevent stiffness that results when edema fluid is

allowed to consolidate into fibrous tissue.

|

|

Figure 73.1. Algorithm for diagnosis and treatment of hand infections. BR–, negative birefringence; BR+, positive birefringence; CBC, complete blood count; CHEM-7, blood chemistries; CPPD, calcium pyrophosphate disease; DIP, distal interphalangeal joint; ER, emergency room; ESR, sedimentation rate; FB, foreign body; IV, intravenous; MCP, metacarpal phalangeal joint; PIP, proximal interphalangeal joint; ROM, range of motion; SQ, subcutaneous.

|

lighting, skilled assistance, appropriate instruments, and anesthesia.

Lancing in the emergency department is of limited use; the extent of

infection in various compartments and tissue planes may not be

recognized and thus go untreated (7,30,35,61). Lancing alone often delays resolution of the infection and leads to further tissue destruction (18,58).

neurovascular structures may be visualized, but exsanguinate by gravity

only; an Esmarch bandage may spread the infection locally and

proximally. Either a regional block or a general anesthetic is

required; local anesthetics in inflamed tissues rarely give adequate

anesthesia.

Antibiotic use alone in initial stages often cures the infection and

prevents serious sequelae. It is vitally important, however, that the

antibiotic be chosen on the basis of the bacteria likely to be found in

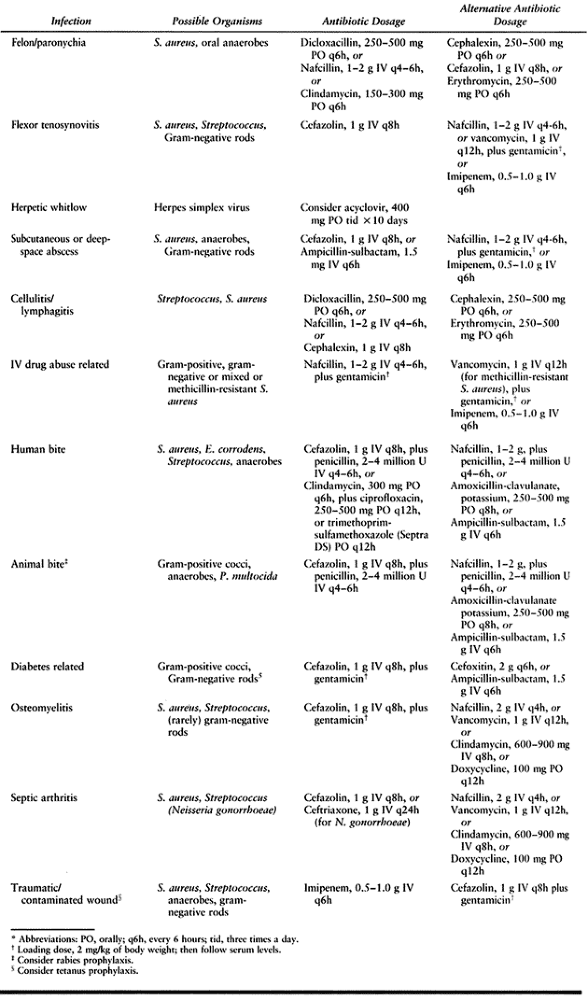

the wound. Gram-positive and gram-negative anaerobic organisms are

often found in hand infections, in addition to the common and

well-known gram-positive aerobic organisms Streptococcus and Staphylococcus (1,9,16,19,20,21,22 and 23,32,38,43,44,50).

|

|

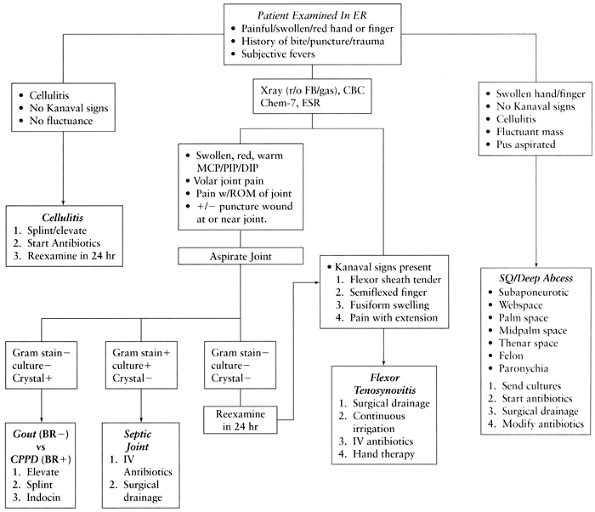

Table 73.1. Empiric Antibiotic Recommendations for Hand Infections*

|

factors: Penicillinase-resistant penicillins (e.g., nafcillin) are

ineffective against many anaerobic pathogens (19,20,22,59). Most hand infections are polymicrobial in nature (Table 73.2) (18,20,59,62). Incorrect initial selection of an antibiotic leads to a poor outcome in hand infections (18,43,58).

|

|

Table 73.2. Organisms Cultured in 175 Hand Infections in Hospitalized Patients

|

subsequently cultured organisms is sufficiently common that Gram stains

should not be used to exclude initial broad-spectrum coverage (43).

Effective anaerobic coverage is provided by penicillin; effective

aerobic gram-positive coverage is provided by either a

penicillinase-resistant penicillin (e.g., nafcillin) or by a

first-generation cephalosporin such as cefazolin (Ancef, Kefzol).

Anaerobic coverage in penicillin-allergic patients is provided by

cefoxitin (Mefoxin) (21). Clindamycin is

bacteriostatic, and although it is effective against many anaerobes, it

is ineffective against an important faculative anaerobic pathogen, Eikenella corrodens (9). Bactericidal agents are preferred.

hand infections, including those in intravenous (IV) drug abusers and

in mutilating injuries in dirty environments, such as that associated

with farm machinery (16,44,52,62). Add an aminoglycoside antibiotic for initial treatment of these types of infections (51).

needed if the patient has not had one in the 5 years before the

infection or injury. If the patient has had no previous immunization,

administer 250 to 500 units of tetanus immune globulin in addition to

tetanus toxoid. Follow up with a complete immunization schedule.

The latter are more common in infections related to IV drug abuse or

contaminated environments such as farms, stagnant lakes, or sewers (16,39,44,52,62). In most hand infections, multiple pathogens are isolated on culture (58). Treat polymicrobial infection (Table 73.2) with broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage from the outset to avoid a poor outcome (18,43,58). Single antibiotic use rarely covers all offending organisms (18,34,59).

except in special circumstances such as clostridial infection in gas

gangrene. Crush injuries that result in infection create an ideal

environment for anaerobic organisms. Gram-positive anaerobic organisms,

such as Peptococcus and Peptostreptococcus, are more frequently recognized, but gram-negative anaerobic bacteria are common isolates in hand infections (Table 73.2), either alone or with Staphylococcus and Streptococcus, especially in clenched-fist and human bite injuries (19,20,22,23,54,58).

important pathogens found in infections associated with IV drug abuse

infections, because of the common practice of using saliva to lubricate

the needle or moisten cotton used to strain impurities (23,44,58).

The aerobic and anaerobic, gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria

that infect hands are numerous, and we again emphasize the need to

consider all pathogens when selecting an antibiotic (7).

health-care workers who deal with the mouth, such as dentists, dental

hygienists, nurses, and anesthesiologists (31). They

are self-limiting, and recognition of them is important to prevent

overtreatment. Laboratory tests can confirm these infections, but the

diagnosis is usually clinical.

related organisms is cell mediated rather than humoral antibody

mediated, and therefore, often presents as a foreign-body—type reaction

or nonspecific inflammation (3,10,12,25,65).

Delay in diagnosis is common, and the diagnosis is often made only

after failure of other treatment modalities. These organisms commonly

infect the synovium. Once the diagnosis has been made, surgical

intervention may be necessary; antibiotic treatment alone, however, is

often indicated.

possible to reduce the deleterious effect of venous congestion. An

abscess, which is usually the result of a puncture wound that

inoculates the subcutaneous tissue, is recognized clinically as a

raised area of erythema and induration with notable fluctuance. When

seen in IV drug users, abscesses of the upper extremity vary in size

and location but are mostly seen on the dorsum of the hand and forearm,

in the antecubital fossa, and near the deltoid insertion at the

shoulder. An abscess must be drained. Hold antibiotics until

intraoperative cultures are obtained.

-

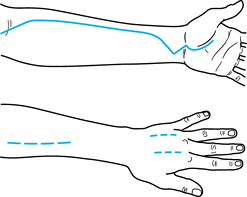

Base the incision over the apex of the

abscess and in such a way that it can be extended proximally or

distally in an extensile fashion because often the abscess proves to be

larger than anticipated (Fig. 73.2). Incisions should be straight and extensile, curving only at skin creases so as to cross them at an angle of 60° or less.![]() Figure 73.2.

Figure 73.2.

Incisions for drainage of subcutaneous abscesses in the hand and

forearm. Incisions are extensile. Only part of the incision may be

necessary, but often the extent of infection is greater than expected. A: Palmar incision. B: Dorsal incision. -

Avoid sharp angles and skin flaps because

they compromise skin already suffering from the decreased perfusion

produced by the edema of the infection. Skin flaps created by surgical

incisions in infection are at great risk for necrosis (55). -

Excise all infected tissue sharply; a

large curet works well to remove the remains after most of the infected

tissue has been sharply debrided. In infections related to IV drug

abuse, identify and excise the thrombosed, infected vein along its

course until uninfected tissue is found. -

Send fluid for Gram stain and aerobic or anaerobic cultures. Then begin IV antibiotics.

-

Irrigate thoroughly with a pulsatile lavage system.

-

Pack the wound and leave it open. Let the

wound close secondarily; the vast majority will contract and

epithelialize readily. For those wounds in which debridement has been

extensive and secondary-intention healing would require a prolonged

period, we recommend a meshed split-thickness skin graft placed over a

completely granulated base at a later time. Delayed closure of a wound

that is not completely resolved often results in recurrence of the

infection because unseen residual infection can no longer drain. The

conditions of abscess are, therefore, recreated. -

Initiate wet-to-dry dressing changes on

the first postoperative day. These dressing changes are initially done

by the nursing staff twice a day. Teach patients to change their own

dressings in preparation for discharge from the hospital. As wound

improvement is noted (decreased edema and erythema), change

administration of antibiotics to the oral route and discharge patients

with instructions to continue wet-to-dry dressing changes at home until

the wound has completely healed.

gangrene or hemolytic streptococcal gangrene, manifests as an

overwhelming infection within a short period of time. Necrotizing

fasciitis is potentially a limb-threatening or life-threatening

infection that more commonly affects patients with diabetes and IV drug

abusers, who are especially at risk because of the decreased

effectiveness of the immune response (2,24,44,52).

The classic signs and symptoms are erythema, pain, advancing

cellulitis, crepitance, skin necrosis, skin bullae, high fever, and

other systemic signs of infection. When these patients are first seen,

they may have a benign-appearing cellulitis. A tender, erythematous,

swollen, and hot area quickly becomes tense, shiny, smooth, and more

painful. Lymphadenitis and lymphangitis are rare (28).

Within a few days, the skin color darkens and blisters, and bullae

develop. These infections are usually associated with a significant

leukocytosis (52). Radiographs may demonstrate soft-tissue gas. One organ system other than the integumentary or musculoskeletal

system often is in failure (e.g., delirium, shock, respiratory failure, or renal failure).

is the most common organism cultured, although mixed aerobic-anaerobic

and gram-positive and gram-negative infections also occur. Although the

bacteriology of this infection may vary, the common mechanism of

destruction is hypothesized to be the ability of the bacteria to

produce various enzymes (i.e., hyaluronidase, lipase) (38).

These bacterial enzymes facilitate necrosis of tissue, mainly fascia

and fat, and thus allow the rapid spread of infection along tissue

planes. Liquefactive necrosis of the fat and superficial fascia in the

subcutaneous space leads to the characteristic appearance of a grayish,

watery, and foul-smelling fluid often referred to as “dishwater pus.”

a significant leukocytosis in a clinically deteriorating patient

suggests the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis, a definitive diagnosis

can be made at the time of surgery by the presence of necrotic fascia (64).

Immediate radical surgical debridement is required until healthy muscle

and fascia are seen proximally beyond the infected area. Absolutely all

infected tissue must be debrided radically if the infection is to be

controlled. Multiple debridements and even amputation may be necessary

as a life-saving measure. The patient may deteriorate rapidly; clinical

vigilance and frequent wound checks are mandatory.

Infection in one compartment generally is manifested by pain and

swelling throughout the hand, with exquisite tenderness in the confines

of the involved space. Knowledge of the anatomic boundaries of these

spaces is important for diagnosis and treatment.

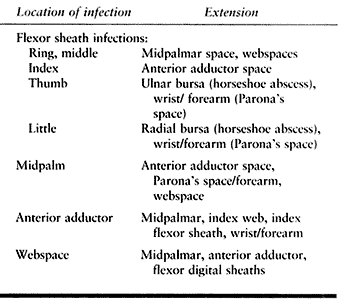

|

|

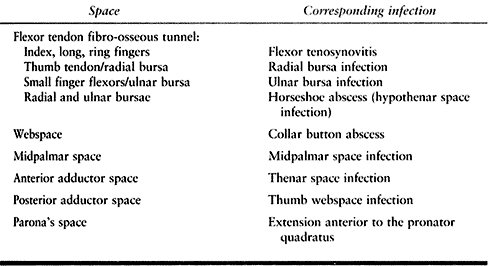

Table 73.3. Spaces of the Hand and Their Infections

|

Adequate assessment, a necessary part of the preoperative examination,

requires that the surgeon be aware of the possible patterns of

extension (Fig. 73.3). Visual inspection offers

clues, but as Kanavel notes, “The most conspicuous and valuable sign is

the extension of the exquisite tenderness to the area involved” (29).

If there is any doubt, exploration of the space where extension may

have occurred is indicated at the time of surgical drainage of the

known infected space.

|

|

Table 73.4. Extension of Space Infections

|

|

|

Figure 73.3. Cross section through the proximal part of the hand demonstrating the palmar fascial spaces. (From Hollinshead WH, Rosse C. Textbook of Anatomy, 4th ed. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1985.)

|

webspace, the dorsal subaponeurotic space, the midpalmar space, and the

thenar space. These closed compartments are susceptible to infection,

usually from direct traumatic inoculation, extension from an infected

contiguous compartment, or less commonly, from hematogenous spread. The

two most superficial deep spaces are the webspace and the dorsal

subaponeurotic space; identifying infection in these spaces is easier;

determining the involved space in the deep palm is more difficult.

erythema over the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the involved webspace;

characteristically swelling is greater dorsally than palmarly because

of the greater suppleness of the dorsal skin. A webspace infection

often occurs from deep spread of a superficially infected palmar

callus. The fingers bordering the webspace involved are splayed because

tissue pressure holds them apart. This type of infection is also called

a collar button abscess after the old-fashioned dumbbell-shaped collar

buttons. The infection begins palmarly, then spreads dorsally around or

through the transverse metacarpal ligament to the dorsal webspace (11).

Thus two abscess spaces are created, connected by a thin stalk. A

neglected webspace infection can spread to the palm spaces through the

lumbrical canals (27).

-

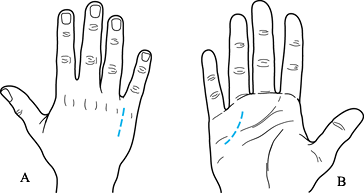

Two incisions are needed (Fig. 73.4).

Palmarly, make an oblique incision following the skin lines. Stay away

from the web edge; an incision into or through the edge will cause

contracture. The abscess is just below the skin, so deeper dissection

is not indicated. Remember that in this area, the neurovascular

structures lie just beneath the skin, so use great care.![]() Figure 73.4. Dashed lines indicate incisions for drainage of webspace infections (A) and dorsal subaponeurotic space infections (B).

Figure 73.4. Dashed lines indicate incisions for drainage of webspace infections (A) and dorsal subaponeurotic space infections (B). -

Spread the margins of the incision gently to allow adequate drainage.

-

Dorsally, make a longitudinal incision

between the metacarpal heads that stays at least 5 mm proximal to the

web edge. Excise the dorsal abscess cavity and break up all loculations. -

Place drains into the incisions after

irrigation. Begin IV antibiotics after fluid or tissue for culture is

obtained. Follow with the usual aftercare.

hand beneath the extensor tendons (29).

Infection usually begins with direct inoculation beneath the extensor

tendons. The patient has dorsal hand swelling and erythema, and often

it is difficult to delineate a subcutaneous infection from one

involving the subaponeurotic space. The deep space is involved unless

proven otherwise and thus should be drained.

-

Make two longitudinal incisions; one over

the second metacarpal shaft and another over either the fourth or the

fifth metacarpal shaft (Fig. 73.2B) to allow better coverage of the extensor tendons dorsally. -

Try to preserve the dorsal veins, which are important to control swelling.

-

Explore deep to the extensor tendons, taking care not to injure them.

-

Allow incisions to heal by secondary intention.

-

Important: Prevent extensor lag by

initiating early motion of the wrist and finger joints. Continue

therapy during the entire healing stage.

Anatomists do not agree on their exact anatomic boundaries. They lie

dorsal to the flexor tendons and palmar to the intrinsic muscles of the

hand, and proximally and distally, they merge to form potential

extensions to other hand and forearm spaces. These extensions are a

source of spread of infection.

Most thenar space infections involve the anterior adductor space. Its

anterior boundary is the index finger flexor tendons and the midpalmar

septum; its posterior boundary is the fascia over the adductor

pollicis. Radially, the thenar intermuscular septum and ulnarly the

midpalmar (oblique) septum complete this potential space (27).

tense swelling in the space. Thumb adduction and opposition decrease

the potential thenar space and cause an increase in pain. Therefore,

the attitude of the hand with a thenar space infection is with the

thumb in palmar abduction (11). Infection in

the thenar space can spread from flexor tenosynovitis of the index

finger. Distinguishing between an anterior adductor space infection and

a posterior adductor space infection can be difficult. Usually, the

anterior space is involved first and as the infection progresses,

purulence tracts over the adductor pollicis to the posterior adductor

space. If there is any doubt, open both spaces.

-

Make a curvilinear incision in the palm parallel to the thenar crease on the ulnar side at the base of the thenar eminence (Fig. 73.5).

-

Gently spread the palmar fascia in line with the incision. Identify and tag the digital nerves and flexors to the index finger.

Figure 73.5. Incision for drainage of thenar space infections.

Figure 73.5. Incision for drainage of thenar space infections. -

Gently retract the nerves.

-

Enter the space beneath the flexors by

blunt dissection, remembering that the superficial and deep palmar

arches and recurrent branch of the median nerve are in this area. -

Open sufficiently to allow easy drainage.

-

Send fluid for aerobic and anaerobic culture, then start IV antibiotics.

-

Irrigate well. Place a penrose drain to keep the space open. Close the skin loosely.

-

Make a longitudinal incision dorsally between the thumb and index metacarpals (Fig. 73.5). Stay away from the edge of the thumb-index webspace to avoid webspace contractures.

-

Incise the fascia, then retract the first

dorsal interosseous muscle ulnarly and the extensor pollicis longus

tendon radially. Take care to avoid the radial artery, which is in the

proximal portion of the incision. -

Bluntly enter the space between the

retracted muscles. Open sufficiently to allow easy drainage. Send fluid

for aerobic and anaerobic cultures, then begin IV antibiotics. -

Irrigate well. Place a Penrose drain to keep the space open. Close the skin loosely.

of the index finger, coursing obliquely posteriorly to its attachment

on the third metacarpal. It divides the palm into the two main spaces

of the anterior adductor (thenar) space and midpalmar space. Midpalmar

space infections (Fig. 73.3) are less common than thenar space infections and occur from direct inoculation of this potential space (11) or spread

from tenosynovitis of the long, ring, or small fingers. The midpalmar

space is bordered anteriorly by the flexor tendons of the ring, long,

and small fingers. Posteriorly, the second, third, and fourth palmar

interossei, the third dorsal interosseus, and the ulnar third and the

entire fourth metacarpal define this space. Its ulnar border is the

hypothenar muscular septum, and the radial border is the midpalmar

(oblique) septum (27).

-

Make a transverse incision parallel and

just proximal to the distal palmar crease, just through the skin at the

ring finger. It will be over the area of the swelling. The digital

neurovascular structures lie just below the skin, so take extreme care

when making the skin incision (Fig. 73.6).![]() Figure 73.6. Incision for drainage of midpalmar space infection.

Figure 73.6. Incision for drainage of midpalmar space infection. -

Once through the skin, gently dissect

longitudinally and identify the digital nerves. Tag these features and

retract them gently. Identify the deep and superficial flexor tendons

to the ring finger. Because the space is dorsal to the flexors, blunt

exploration radial and deep to these tendons will gain entrance into

the space. -

Spread gently and open sufficiently to

allow adequate drainage. Send fluid for aerobic and anaerobic cultures,

then begin IV antibiotics. -

Irrigate, and place a Penrose drain to keep the space open. Close the skin loosely.

appropriate, and prompt treatment to avoid severe disability of the

digit or amputation. Acute flexor tenosynovitis is an infection of the

tendon sheath that surrounds the flexor tendons. The synovial sheath

consists of a visceral layer or epitenon that is adherent to the tendon

and a parietal layer, which join at their most distal and proximal

ends. The sheath extends from the midpalmar crease (metacarpal neck) to

just proximal to the distal interphalangeal joint. The small finger

flexor sheath is continuous with the ulnar bursa in the palm that

surrounds the superficial and deep flexor tendons. The sheath around

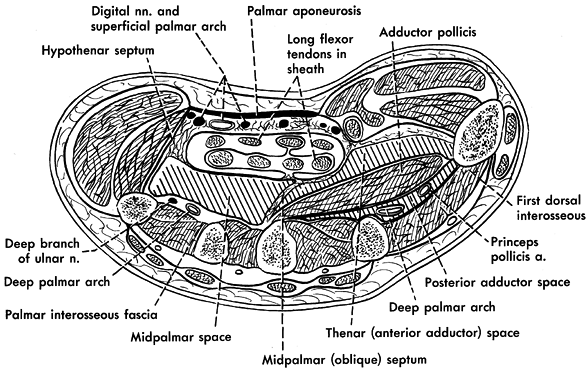

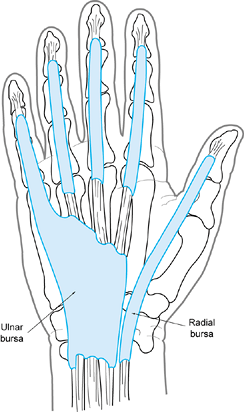

the flexor pollicis longus is continuous with the radial bursa (Fig. 73.7).

Both of these palmar bursae extend just proximal to the transverse

carpal ligament and, in 80% of individuals, they communicate (42).

|

|

Figure 73.7. Anatomy of the radial and ulnar bursae.

|

innocuous-appearing small abrasions and tiny punctures; do not be

fooled. These minor wounds are the indication that the sheath has been

inoculated with bacteria. The ring, long, and index fingers are most

commonly involved; however, any digit may be affected. Kanavel (29) described four cardinal signs of infection of the flexor sheath:

-

Symmetric, fusiform swelling of the entire finger (sausage finger)

-

Semiflexed position of the digit

-

Exquisite tenderness over the course of the sheath

-

Exquisite pain on extending the finger

early cases, only one or two of these may been detected. The most

reliable sign is tenderness over the flexor sheath (42).

examine the other spaces of the hand as well, because extension of a

sheath infection can occur into the palmar

spaces,

webspace, carpal canal, palm bursa, and Parona’s space (see later).

Although spread to any of the hand spaces can occur, typically flexor

sheath infections of the middle, ring, and small fingers extend into

the midpalmar space, and index finger infections extend into the

anterior adductor space (thenar space).

allow continued drainage without compromising the function and anatomy

of the delicate structure that is the flexor tendon and its canal.

Drainage can easily be accomplished, but the drainage procedure itself

must not be detrimental to the sheath if the smooth gliding of the

flexor tendon within the sheath is to occur after eradication of the

infection. We believe that this technique is best accomplished through

the intermittent irrigation of the sheath using a catheter (41,42).

advantage of constant cleansing of the sheath. If fluid does not drain

easily from the distal wound, it can be hydraulically forced into the

sheath and surrounding tissues. Intermittent irrigation requires the

observation of ready egress while infusing to avoid this potential

problem. Antibiotic irrigation within the sheath is not recommended

because it has not been proven to be superior to saline irrigation

alone. Also, the effect of antibiotics on the flexor sheath with

respect to inducing adhesions has not been studied.

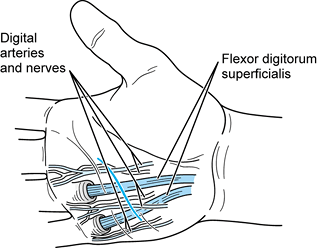

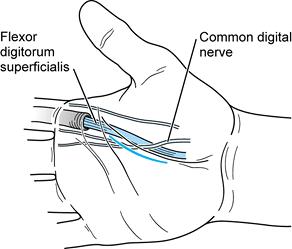

-

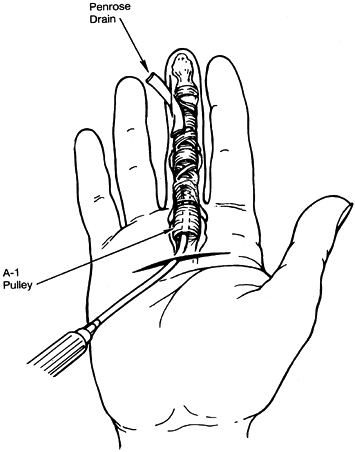

Use two incisions (Fig. 73.8). Make a transverse incision proximally in the area of the A1

flexor pulley (metacarpophalangeal joint). This incision is made at the

proximal palm crease in the index finger, at the distal palmar crease

in the ring finger, and between the two for the long finger. Incise the

skin only about 1 cm in length.![]() Figure 73.8. Closed tendon sheath irrigation for flexor tenosynovitis.

Figure 73.8. Closed tendon sheath irrigation for flexor tenosynovitis. -

Gently dissect longitudinally in line

with the palmar fascia (perpendicular to the incision), locating the

digital nerves on either side of the tendon. Tag and gently retract

them. -

Identify the tendon and the A1

pulley in the base of the wound. Open the palmar synovial and fibrous

covering that is the beginning of the flexor sheath; pus or, more

commonly, slightly cloudy fluid will egress. Send a sample for culture;

then start IV antibiotics. -

Make the second incision along the

midlateral line of the digit on the ulnar side at the distal

interphalangeal joint crease of the index and long fingers, or the

radial side of the ring and little fingers. The midlateral line is that

line created by connecting the dots that can be made at the end of the

flexion creases when the finger is maximally flexed. Incise the skin.

Bluntly dissect deeper to enter the flexor sheath. -

At the proximal wound, lift the A1 pulley and thread a small catheter (#10 pediatric feeding tube fenestrated on its end) into the sheath for about 2 cm.

-

Attach a syringe to the catheter end in

the palm and irrigate saline through the catheter. Fluid should easily

exit from the distal wound. If it does not, reposition the catheter or

enlarge the opening distally. Several positioning attempts may be

needed to achieve easy flow. -

Irrigate at least 500 ml of normal saline through the sheath to thoroughly cleanse it.

-

Place a rubber wick made from a Penrose

drain into the sheath through the distal wound to prevent closure.

Suture the wick distally and the irrigating tube proximally to the skin

to prevent their accidental removal. Approximate the proximal wound

with one or two nylon sutures. -

Apply a bulky hand dressing that allows

visualization of the distal wound but covers the palmar wound, and

bring the catheter out through the dressing.

over 30 to 60 seconds through the catheter every 2 to 4 hours.

Postoperative orders should include nursing precautions that when

irrigating the catheter with saline, resistance to flow should be

minimal, that egress should be seen, and that the patient will

experience some discomfort. If resistance is excessive, flow is not

seen distally, and the patient experiences excessive pain, the catheter

may have

become

kinked or may have moved to an inappropriate area. Remove the catheter

if easy flow cannot be regained. Continue the irrigation until the

sheath is nontender (36 to 72 hours), then remove the catheter and

wick, and apply a moist dressing for 2 to 3 more days, continuing IV

antibiotics. Begin active range-of-motion exercises of the digit after

catheter removal to prevent stiffness. Allow the wounds to close

secondarily.

The proximal extension of the thumb flexor sheath is the radial bursa.

It extends proximal to the transverse carpal ligament. The proximal

extension of the small finger flexor sheath is the ulnar bursa that

also surrounds the superficial and deep flexor tendons and extends

proximal to the transverse carpal ligament as well. As stated earlier,

in approximately 80% of individuals, these bursae communicate.

Infection that spreads between these two bursae can create a “horseshoe

abscess.”

present in the digit; in addition, there is swelling, tenderness, and

calor into the respective side of the palm and wrist. Treat these

symptoms with catheter irrigation as described earlier; described below

are the modifications appropriate to the anatomy of each digit and its

bursa.

-

Make a distal thumb incision along the

radial side at the interphalangeal joint crease. Stay dorsal to the

neurovascular bundle. Identify and enter the flexor sheath. -

Pass a probe or other blunt instrument

carefully down the canal until it presses up at the palmar wrist

crease. Do not push the probe if you meet resistance. Gently redirect

it. Make a longitudinal incision that does not cross the wrist crease. -

Enter the space and identify your probe.

-

Pass a #10 pediatric feeding tube from

proximal to distal for about 2 cm. Suture a wick distally and the

irrigation tube proximally, as described for suppurative flexor

tenosynovitis. -

The rest of the procedure is the same as

for flexor tenosynovitis. Do not hesitate to make an additional

incision in the palm if threading the catheter is difficult.

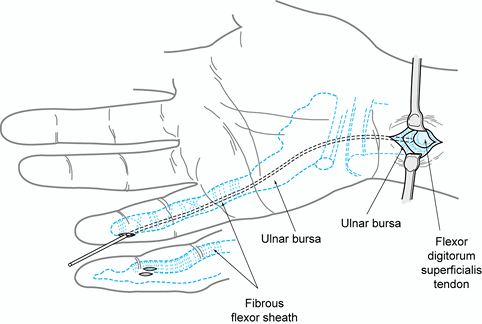

that for a radial bursa, except the distal incision on the small finger

is on the ulnar side of the digit at the distal interphalangeal joint (Fig. 73.9).

|

|

Figure 73.9. Drainage of ulnar bursa infection and insertion of irrigation catheter.

|

forearm between the deep flexor tendons and the pronator quadratus. It

is usually infected only as a result of proximal extension of a hand

space infection. With deep space palmar infections, always palpate

Parona’s space for fullness and tenderness. Clinically, infection is

evident by tenderness in the distal forearm with pain on pronation and

supination. Drainage is accomplished by an incision at the wrist and

proximal forearm that often includes communication with the proximal

portion of one of the bursa or palmar space infections. Bluntly dissect

deep to the flexor tendons to enter the space. Enlarge sufficiently to

allow adequate drainage.

detected before fulminant proliferation of bacteria, aspiration for

diagnosis and culture can be followed by antibiotic therapy alone.

Medical literature documents the ability to eradicate the infection by

antibiotics alone. The deleterious effect of pus on cartilage, however,

necessitates surgical drainage if there is any doubt that the infection

has been detected and treated early enough. Septic arthritis or

infection of a joint space may affect any of the joints in the digits,

thumb, or wrist. It is most likely secondary to direct penetration of

the joint capsule, but hematogenous spread occurs as well. If there is

no history of a bite, puncture near the joint, or a recent laceration,

it is important to ask the patient about recent tooth abscesses, ear

infections, other skin infections, gastrointestinal (GI) infections,

and genitourinary (GU) infections. Gonococcal septic arthritis can be

treated with antibiotics alone; it is important to question the patient

about his or her sexual history.

erythematous, and warm digit, thumb, or wrist, localized to a specific

joint. The pathognomonic sign of joint infection is exquisite pain on

attempted motion of that joint. Cellulitis over a joint causes pain on

motion, but the tenderness elicited by slow, gentle, passive motion in

cellulitis is much different from the severe pain caused by any attempt

at motion of an infected joint.

following joint aspiration. Send the aspirate for cell count with

differentiation, Gram stain, anaerobic and aerobic culture, glucose,

and crystal analysis. A white blood cell differential of greater than

50,000 (usually more than 75% segmented neutrophils), or the presence

of bacteria on Gram stain or culture is diagnostic. A synovial fluid

glucose of 40 mg less than the fasting blood glucose is consistent with

an infectious process (53). Finally, a crystal analysis is necessary to rule out gout or pseudogout as a cause of the painful, red, swollen joint.

the joint, ideally an 18 gauge needle or larger. A 20 or 22 gauge

needle is usually the largest that will gain entrance into smaller

joints. The joint space for the metacarpophalangeal joint is easily

palpated just ulnar or radial to the extensor hood; take the edge of

your fingernail and press. Aspirate after an antiseptic preparation.

Giving a local anesthetic usually causes more discomfort than the

single stick of the aspirating needle, but patients are not easily

convinced of this fact.

similar fashion. This location just next to the extensor tendon

dorsally would correspond to a 10 o’clock or 2 o’clock position if the

extensor tendon (top or dorsal) is considered as 12 o’clock.

-

Use a large needle, ideally 18 or 20 gauge, or the largest needle that will enter the joint space.

-

Palpate the joint space for the

metacarpophalangeal joint, ulnar or radial to the extensor hood with

the edge of your fingernail, feeling for the depression of the joint

space. -

Aspirate after an antiseptic wash.

-

Locate the interphalangeal joint in a

similar fashion. Enter at the 10 or 2 o’clock position, with the

extensor tendon as 12 o’clock. -

Aspirate after an antiseptic wash.

-

Base the incision dorsally over the involved joint.

-

Incise longitudinally through either the

extensor tendon at the metacarpophalangeal joint or through the

extensor mechanism at the proximal or distal interphalangeal joints. -

Enter the involved joint and thoroughly irrigate it.

-

Leave a small wick (penrose drain) in the

joint space to facilitate drainage. Reapproximate the extensor

mechanism and loosely close the skin. -

Remove the penrose drain in 48 to 72 hours.

ulnocarpal, and midcarpal joints. Septic arthritis may be found in any

one or all of these joints; these spaces may or may not normally

communicate. Direct the preoperative examination toward localizing the

joint or joints involved. Pronation or supination pain indicates

involvement of the radioulnar joint; flexion or extension pain

indicates involvement of the radiocarpal, ulnocarpal, or midcarpal

joints. Aspiration with an 18-gauge needle confirms clinical

suspicions. The radial and ulnar styloids offer convenient landmarks;

enter just distal to them.

-

Enter the radiocarpal, radioulnar,

midcarpal, and ulnocarpal joints through either a transverse or

longitudinal dorsal skin incision. A transverse incision has the

advantage that if you take care to isolate and preserve veins, you can

make a completely circumferential incision so that all wrist joint

spaces can be entered until the infected space can be found and drained. -

Make the skin incision, and then enter

the joint space by blunt dissection between the appropriate extensor

compartments. Enter between the third (extensor pollicis longus) and

fourth (extensor indicis proprius, extensor digitorum communis)

compartments to drain the radiocarpal, radioulnar, and midcarpal

joints. Enter around the extensor carpi ulnaris or extensor digiti

quinti tendons to drain the ulnocarpal joint. -

Send fluid for aerobic and anaerobic cultures. Begin IV antibiotics.

-

Irrigate thoroughly with a pulsatile lavage system.

-

Place a closed suction system drain.

Close the joint capsule and skin incision over the drain. Leave the

drain in for 3 to 5 days. -

Begin gentle active assisted and active range-of-motion exercises after drain removal.

-

Continue IV antibiotics for a least 1

week. Follow with an oral agent for several weeks after hospital

discharge. Antibiotic sensitivities and minimum inhibitory

concentration (MIC) help guide the appropriate oral antibiotic regimen.

Ideally, the oral dose will have been determined by greater than 1:8

serum bactericidal levels against the bacterium or bacteria isolated.

have significant sequelae if they are not recognized and treated

correctly (6,7,15,19,22,23,34).

There are four classic mechanisms of infection, and these include

self-inflicted (caused, for example, by nail biting), traumatic

amputation (usually at the distal interphalangeal joint or pulp) from a

bite, full-thickness bite wounds on any part of the hand, and finally a

clenched-fist bite injury, usually following an altercation (14).

The complications of incompletely treated human bite infections include

arthritis, joint stiffness, osteomyelitis, toxic shock syndrome, and

infrequently, death. Human mouth organisms inoculated into tissue are

quite virulent (6,7,13,15,19,22,23,33,34 and 35,58,63).

control a human-bite infection occurred in up to half of the affected

patients. Death secondary to morsus humanis was reported as well. The

introduction of antibiotics has not eliminated the complications

associated with these infections. Even with antibiotics, 6% of human

bites need amputation to control infection, 4% require late amputation,

and 28% develop either osteomyelitis or other causes for stiff,

disabled fingers (34).

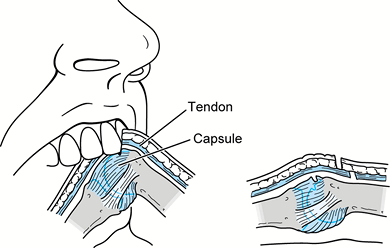

and the overlying dorsal skin and extensor tendon stretched distally.

The tooth penetrates the skin, part or all of the tendon, the dorsal

joint capsule, and potentially the metacarpal head. With the hand open,

it may be difficult to recognize the extent of injury because the

injury to the joint capsule and bone may be distal to the skin

laceration and injury to the extensor tendon is proximal to the skin

laceration (Fig. 73.10). Often, there is

intra-articular violation with the potential for septic arthritis.

Sometimes, osteochondral fractures of the metacarpal head or fracture

of the metacarpal head or neck occur. The clenched-fist injury commonly

involves the metacarpophalangeal joint of the long, ring, or little

fingers, but any hand joint or digit can be involved.

|

|

Figure 73.10. A fight bite occurs during flexion (A) of the metacarpophalangeal joint. During extension (B) of the injured joint, the tendon or osteochondral injury may be obscured leading to a closed intra-articular injury.

|

(i.e., in less than 24 hours) have a better prognosis than those seen

later than 24 hours from the time of injury (29,34).

Clenched-fist injuries may resemble a simple puncture wound over the

metacarpohalangeal joint, but there usually is more extensive damage to

the soft tissue and bony structures underneath.

A plethora of microbes are isolated from the human mouth flora,

however, and thus it is not uncommon to see mixed infections that could

include, Bacteroides sp., Neisseria sp., Clostridia sp., spirochetes, Micrococcus, and rarely, Actinomyces (19,20,22,34,40).

the most common pathogen in human bite infections, it certainly seems

to be the type most often associated with “fight bites.” E. corrodens has been isolated in 7% to 29% of human bite infections (4,20,47). Although it is a normal part of the human mouth flora, it is more readily cultured from dental scrapings than from saliva (47). It is a gram-negative rod and a facultative anaerobe and thus grows best in 10% CO2.

radiographs to rule out a fracture or foreign body (i.e., tooth), and

wound exploration. Dorsal puncture wounds around the metacarpohalangeal

joint are considered to be clenched-fist injuries unless proven

otherwise.

joint to determine extensor tendon involvement. A saline arthrogram may

assist in determining joint involvement. A history of a human bite or

lacerations (especially over a joint) obtained during a fight must be

treated aggressively. Treatment requires surgical debridement of dead

or questionably viable tissue and thorough irrigation of the

subcutaneous space (especially a joint). Leave the wound open.

First-generation cephalosporins such as cefazolin, cephalothin, and

cephradine, or penicillinase-resistant penicillins are effective

against the common gram-positive aerobic bacteria. Many anaerobes

commonly isolated from clenched-fist and human bite infections,

however, are resistant to penicillinase-resistant penicillins and

clindamycin, which are common first choices in the treatment of skin

infections (9,49,60).

The antibiotic of choice for these anaerobes is penicillin. Cefoxitin

is effective against gram-positive aerobic bacteria and the anaerobes

described, so it may be used as a single agent for penicillin-allergic

patients (21).

-

Extend the traumatic wound proximally and distally.

-

Remove the necrotic and infected tissue

from the subcutaneous layer. The infraction often extends beyond the

obvious site of injury. Explore nearby potential areas of invasion such

as the dorsal subcutaneous space. -

Always open the joint if the injury is

over or near a joint. The joint often appears uninvolved until

arthrotomy is performed and the pus wells out. Enter the joint

dorsally, making a 1 cm longitudinal incision in the capsule through

the extensor tendon. -

Inspect the cartilaginous surfaces for

lesions. An osteochondral defect or tooth indentation is common. Record

such a finding and also the condition of the cartilage in the operative

record. Divots and unhealthy-appearing cartilage are poor prognostic

factors. -

Irrigate thoroughly by pulsatile lavage. Leave the wound open.

(more commonly from cat than from dog bites). The presence of

cellulitis, lymphangitis, serosangueinous, or purulent drainage within

12 to 24 hours after a cat or dog bite strongly suggests P. multocida as the offending organism (1).

debridement of necrotic and damaged tissue. Be sure to culture the

wound even if gross purulence is not found. Penicillin is the drug of

choice for P. multocida, with tetracycline

and cephalosporins as alternatives. Administer penicillin intravenously

in combination with cefazolin; alternatively, amoxicillin-clavulanate

potassium can be given orally for less severe infections (Table 73.1).

the skin of the pulp lies fat. Numerous fibrous septae that tether the

skin to the bone cause compartmentation of the fat to make

shock-absorbing spaces. Infection in the digit pulp is therefore a

series of small, closed-space infections, each needing incision and

drainage. A felon is usually due to penetrating trauma to the tip of a

digit. S. aureus is the most common organism found (45).

The presenting symptom is an erythematous, swollen distal phalanx on

the palmar side of the digit. It is important to distinguish a felon

from herpetic whitlow, because the treatment of herpetic infection of

the distal phalanx is nonsurgical. When the felon has organized into an

abscess, drainage is indicated.

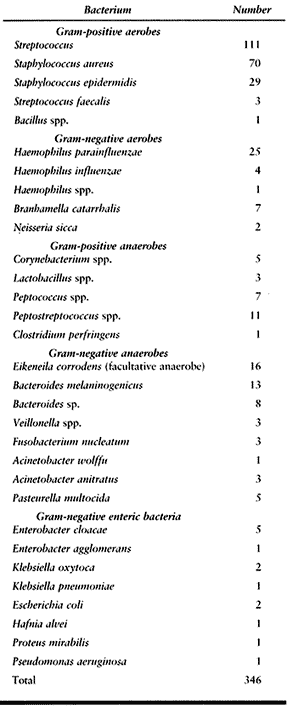

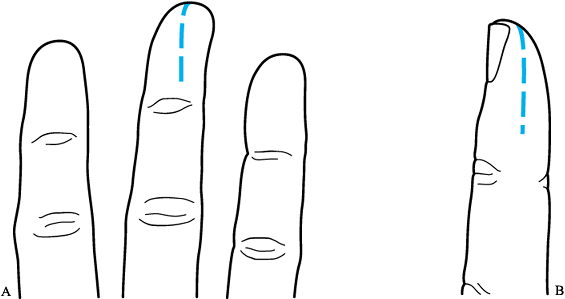

-

Drain a felon that points palmar and midline by a midline approach (Fig. 73.11A). Drain a felon that does not point midline with a midlateral incision (Fig. 73.11B). Avoid the “fish-mouth” incision, because it destabilizes the pulp and can cause flap necrosis.

Figure 73.11. Incision for drainage of a felon. All septae must be cut to allow appropriate drainage. A: Midline incision. B: Midlateral incision.

Figure 73.11. Incision for drainage of a felon. All septae must be cut to allow appropriate drainage. A: Midline incision. B: Midlateral incision. -

Incise deeply all the way to the bone and

all the way across the pulp to open all compartmentation spaces. Send

fluid or tissue for culture. Begin antibiotics and irrigate thoroughly. -

Leave the wound open. Place a wick into

the wound. Apply a bulky hand dressing to immobilize the hand for the

first 24 to 48 hours. -

Remove the wick and begin whirlpool soaks

four to five times a day. Apply a finger dressing incorporating damp

gauze next to the wound. Encourage active finger and hand motion.

area sensitive to the disruptive influence of daily living and nail

cosmetic practices, especially in those whose work

or

habits cause a continually damp or wet environment. Bacteria invade the

fold of skin over the nail matrix, producing the characteristic lesion

of inflammation, pain, and swelling. When it is confined to a side of

the nail and involves the fold of skin and not the nail, the infection

is called a paronychia. When it involves the base of the nail fold, it

is an eponychia. Sometimes both sides of the nail and the eponychial

fold are involved, and this infection is called a runaround abscess.

involves the nail bed is a subungual abscess and has more serious

implications The localized superficial nail skinfold infection is not

serious, but deep infection may invade bone and result in nail

destruction, osteomyelitis, and amputation. A patient with a nail bed

infection has swelling, pain, and erythema at the base of the

fingernail or on the side of the nail. The bacterium that infects is

almost exclusively Staphylococcus, except in children, in whom mouth flora can infect as well because of thumb-sucking (8).

returns as a felon. Infection spreads from the nail bed to the pulp of

the digit through bone; if such spread occurs, osteomyelitis of the

distal phalanx is present.

process. Women who work with their hands in moist environments are more

susceptible. The infection comes and goes throughout its course and

leads to a painful thickened eponychial fold that sometimes accumulates

whitish thick material. Most often, Candida albicans

is the offending yeast. Conservative treatment of topical steroids and

antifungals has met with limited success. Chronic paronychias often

require marsupialization.

-

After metacarpal block, use a Freer

elevator or other blunt instrument and, beginning distally, elevate a

few millimeters of the nail fold from the nail as far proximally as the

infection extends. A blunt instrument helps prevent scoring that can

later produce nail ridging. (Note: An incision usually is not needed

for simple cases. A more extensive abscess may need a small incision

adjacent to the eponychial fold and parallel to the nail plate.) -

Using an 18-gauge needle, prick the

infected area to drain and break up loculations. Expect only a few

drops of pus. Send these drops for culture, and begin an antibiotic

effective against Staphylococcus. -

Cover the drained area with

antibiotic-impregnated gauze and place it under the nail fold to allow

continued drainage. Begin soaks in 24 hours and continue until healed.

-

Use a digital block. Perform an eponychial marsupialization by excising a small crescent-shaped piece of the eponychial fold.

-

Remove the skin and thickened tissue down to, but not including, the germinal matrix.

-

If the nail plate is involved (damaged), remove the entire nail.

-

Place xeroform gauze under the nail fold to promote drainage and keep the nail fold from closing.

-

If the nail has been elevated off the

matrix by infection, a subungual abscess is present. Incise along the

borders of the nail fold. Elevate the nail fold (Fig. 73.12).![]() Figure 73.12.

Figure 73.12.

Incision for drainage of a subungual abscess. After folding back the

eponychium, the proximal nail plate is cut with scissors and removed. -

Remove the overlying nail plate to allow

adequate drainage. If there is any question as to the extent of the

subungual abscess, remove the entire nail. Remember, gently free the

nail plate from the matrix with a blunt instrument to avoid injury to

the matrix, which may result in ridging of the nail as it grows back. -

After removing nail plate, scoop the abscess contents out with a curet, gently scraping the surface of the nail matrix.

-

If the nail is removed from the nail fold, place xeroform gauze under the nail fold.

-

Request aerobic and anaerobic culture on the fluid. Begin IV antibiotics.

It is most commonly seen in health care providers exposed to oral

secretions such as dentists, nurses, and dental hygienists. Pain is the

initial symptom. Vesicles 1 to 2 mm in diameter containing clear fluid

occur on an erythematous base; as the infection progresses, the

vesicles coalesce into bullae. The fluid may turn cloudy after being

initially clear, but it is never purulent. Purpuric lesions can develop

beneath the nails. Lymphangitis and lymphadenopathy may also occur and

confuse the picture, simulating a bacterial infection. The pain

continues for 2 to 4 weeks, with decreasing erythema. The hemorrhagic

areas crust and then desquamate, leaving normal tissue.

of the vesicles, which grow characteristic plaques within 1 to 3 days.

Serum titers of antibody to herpesvirus over 2 to 3 weeks may rise to

greater than four times normal levels.

incision and drainage are performed, no purulence will be expressed,

and deeper tissues will be exposed to the herpesvirus. An aggressive

secondary bacterial infection then occurs all too often as the incision

injures tissue that has already been compromised by the edema,

pressure, and unhealthy conditions the viral “cellulitis” has created.

Expectant observation is the key to treatment. Antiviral agents are not

indicated.

These infections typically occur in middle-aged people with a history

of a puncture wound within 6 weeks of onset of symptoms. M. marinum is the most common atypical pathogen, and inoculation usually occurs in a seacoast environment or dock area (26).

Although most atypical mycobacterial infections involve the skin,

deeper structures are susceptible. Tenosynovial infections as well as

bone and joint involvement have been documented.

systemic response, and thus, constitutional symptoms of infection are

not present. Leukocytosis and an elevated sedimentation rate are rare.

Pain, limitation of motion, and fullness of the involved area are

noted, but signs and symptoms are intermittent. Skin infections are

often associated with dermal or subdermal granulomas, which are the

hallmark of diagnosis (26). Synovium is

commonly involved. The synovitis is out of proportion to the disease

initially suspected, such as collagen vascular disease, or nonspecific

inflammatory synovitis. Fistulae may be present. Tenosynovial

infections most commonly involve the flexor tendon sheaths of the

fingers. Patients describe chronic swelling of the involved digit.

Although pain is mild, the bulky synovium may interfere with finger

function, and motion may be limited.

the key to diagnosis of atypical mycobacterial infections in the hand

is biopsy and culture of the suspicious tissue. Diagnosis is based on

finding Langhans’-type giant cells in tissue and the presence of

acid-fast bacilli and positive culture; culture results take at least 6

weeks. Diagnosis is thus typically delayed and is made only after

failure of response to initial treatment. Because cultures may take

more than 6 weeks to grow, medical treatment is often initiated before

definitive culture results if clinical suspicion is high.

biopsy is obtained; complete surgical synovectomy is indicated if the

synovium is heavily affected. Prolonged antituberculous therapy is

recommended with two bactericidal antituberculous agents. Current

antituberculous regimen consists of 2 months of isoniazid, ethambutol,

and rifampin, followed by 7 months of isoniazid and rifampin.

Sensitivities may vary, and medical treatment recommendations change

and thus should be coordinated in consultation with an infectious

disease specialist.

implantation of the fungus or its spore into the skin, or as part of

systemic spread, usually from a primary pulmonary infection that began

with inhalation of spores (10,65). Fungal infections can be divided into cutaneous lesions, subcutaneous infections, and deep or systemic infections (48).

found most often in gardeners and others engaged in activities around

soil, where fungi are ubiquitous. Cutaneous lesions are caused by

dermatophytes that colonize nonliving cornified appendages such as

skin, hair, and fingernails. Examples include dermatophytic infection

of the glabrous skin (tinea corporis), the interdigital areas of the

palms (tinea manuum), and the fingernails (onychomycosis or tinea

unguium) (48). A scaling, pruritic skin lesion

(usually not responsive to or exacerbated by topical steroids) is

present on an obvious thickened and deformed fingernail. Potassium

hydroxide microscopic slide preparations may provide a preliminary

diagnosis, but fungal cultures need to be performed for a definitive

diagnosis.

topical antifungal cream such as tolnaftate, miconazole, clotrimazole,

or econazole. Have the patient apply it topically for 4 to 6 weeks.

More severe or unresponsive lesions may require systemic griseofulvin

or ketoconazole. Fingernail infections are resistant to treatment, but

long-term systemic griseofulvin has met with the most success, with

cure rates as high as 80%.

occurs after trauma or can actually be a systemic manifestation of a

primary lesion elsewhere. After traumatic implantation and an

incubation period of several days to months, a subcutaneous nodule

appears that may or may not be painful. A fistula or ulceration

develops and enlarges with a raised, discolored, and verrucous border.

Epithelial hyperplasia follows. Lymphatic invasion can occur; the lymph

channels become cordlike. Nodules develop, ulcerate, and then

spontaneously resolve, only to be replaced by new lesions.

chromomycosis, mycetoma, and phycomycosis, also produce hand infections

The most common subcutaneous fungal

infection is sporotrichosis (48). Sporotrichosis classically occurs after a prick from a rose thorn by subcutaneous inoculation of the spores of Sporothrix schenckii. After the S. schenckii

organism incubates for a period of days to months, a small, nontender,

movable, subcutaneous nodule develops. Epidermal infection ulcerates

early, whereas a more subcutaneous nodule discolors, darkens, and then

erupts through the skin. Spontaneous healing of the ulcer follows, but

new lesions erupt. Lymphatic invasion occurs, raising cordlike tracks

along the hand and arm. The other cutaneous mycoses present in a

similar fashion.

biopsy of one of the lesions or by culture of drainage. A definitive

diagnosis of sporotrichosis requires S. schenckii

to be isolated on fungal culture. The treatment of choice is potassium

iodide for 6 to 8 weeks. Itraconazole has recently been shown to be

effective as well, and because its dosage is only once a day, it may

prove to be more tolerable.

basis most commonly as tenosynovitis, septic arthritis, or

osteomyelitis. Definitive diagnosis requires identification by a fungal

culture, and treatment usually involves IV amphotericin B for more

virulent fungal infections and oral ketoconazole or itraconazole

treatment for more benign infections.

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) were reported in persons

older than 13 years old from 1981 through 1996, according to the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV/AIDS Surveillance

Report. The true incidence of human immunodefiency virus (HIV)

infection currently exceeds 1 million people.

the HIV-positive person, there is a known high prevalence of infections

in this population. At one institution, nearly 20% of patients

hospitalized for upper extremity infections were HIV positive. An even

more alarming discovery is that less than 10% of these individuals

admitted to being HIV positive (56).

common risk factor for HIV infection, it also was the most common cause

of upper extremity infections in the HIV-positive person (36).

Although these infections may present atypically, the responsible

organisms are usually similar to those that infect the immunocompetent

host, with S. aureus being the most common pathogen (36).

Furthermore, spontaneous infections may occur, herpetic infections may

appear more virulent, and seemingly benign infections may need a more

aggressive surgical approach. Any individual with an unusual hand

infection should be tested for HIV infection.

It is caused most often by open fractures or spread from neighboring

infected soft tissues. The infection rate in open fractures ranges from

1% to 11%, with a higher risk coming from the more contaminated wounds

with more severe soft-tissue injury (17,39). Although S. aureus and Streptococcus remain the most common pathogens, open injuries predispose to gram-negative, anaerobic, and polymicrobial organisms.

clinical indications of osteomyelitis. Systemic manifestations are less

common but include fever, an elevated white blood cell count with or

without an increase in polymorphonucleocytes, and an elevated

erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Radiographic evidence of osteomyelitis

is usually seen in the subacute or chronic state and includes the

presence of periosteal new bone formation, osteolysis, or a sequestrum.

A bone scan is more sensitive and can suggest the presence of

osteomyelitis much earlier than plain radiography (46).

Diagnosis may be made by subperiosteal aspiration of pus, but negative

findings on aspiration do not rule out the possibility of infection.

surgical drainage, followed by antibiotics. Acute osteomyelitis may

initially be treated with antibiotics, immobilization, and elevation.

Failure of an early and discernible response warrants surgical

incision, but cultures taken following the administration of

antibiotics are usually not helpful.

intervention. A sequestrectomy, diaphysectomy, and even digit or ray

amputation are potential interventions to help control and eliminate

infected bone. Staged procedures with antibiotic-impregnated

polymethylmethacrylate spacers, followed by bone grafting and skin

coverage, are sometimes necessary. Local rotational and free flaps

allow subsequent elevation for reconstruction and are preferred to

pedicled flaps. They must be placed in a clean and vascularized wound

bed.

to promote drainage. Apply a plaster splint–reinforced long-arm bulky

hand dressing, incorporating a cord to permit continuous elevation.

Change the dressing at 36 to 48 hours to a maceration-type dressing of

25% strength Dakin’s solution, which is changed daily. Begin active

hand motion to prevent stiffness. Discharge the patient

when the wound is without erythema, tenderness, induration, or swelling.

for the open wounds; antibiotics are prescribed on the basis of culture

results and the disease process. Continue dressing changes until the

wound is healed.

failure to improve after initial debridement. Physical examination

directed toward discovering possible places of spread before surgery

will help uncover these extensions. When in doubt, open the space at

the time of surgery.

drainage must cross the crease, angle it less than 60°; failure to do

so results in contracture. Do not penetrate the webspaces for the same

reason.

or paronychia. Incision of this already-compromised tissue may lead to

secondary bacterial infection.

as well as the anaerobic streptococci, is necessary. Gram-negative

anaerobes are often present, especially in clenched-fist, human bite,

and IV drug abuse infections. Initial antibiotic selection should be

based on the type of injury known or suspected. Think of HIV infection

in the IV drug abuser or the patient who is not improving in spite of

customary treatment.

scheme: *, classic article; #, review article; !, basic research

article; and +, clinical results/outcome study.

SF, Elliott RC, Brand RL, Adams JP. Experience with Atypical

Mycobacterial Infection in the Deep Structures of the Hand. J Hand Surg [Am] 1977;2:90.

JM, Keele BB, Fridovich I. An Enzyme Based Theory of Obligate

Anaerobiasis: The Physiological Function of Superoxide Dysmutase. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1971;68:1024.