Indications for Upper Extremity Blocks

II – Single-Injection Peripheral Blocks > A – Upper Extremity > 5

– Indications for Upper Extremity Blocks

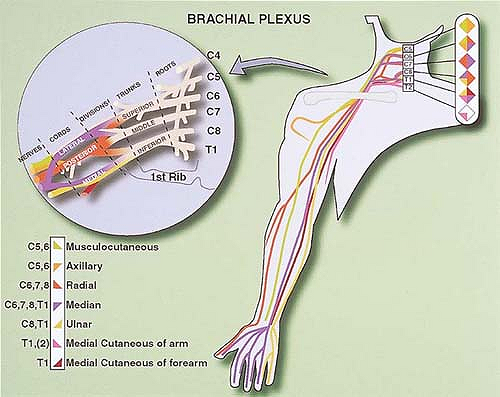

frequently based on either a block of the brachial plexus

(interscalene, supraclavicular, and classical infraclavicular) or a

block of terminal nerves (median, ulnar, radial, and musculocutaneous

nerves) at either the axilla (axillary block) or proximal part of the

humerus (high-humeral approach). The choice of the approach often

depends on the patient’s condition, the surgical indication, and the

anesthesiologist’s experience. In this regard, it is important to

recognize that for surgeries at the wrist and fingers scheduled for

less than 30 minutes, a more distal approach either at the elbow or the

wrist may satisfy all surgical requirements and allow for specific

blocking of the nerve(s) implicated as well as for a preferential

sensory block (at the wrist), preserving the motor function and

allowing the patient to move his or her fingers at the request of the

surgeon (release of trigger fingers). This “hyperselective” approach to

regional anesthesia has been proven to be safe and effective and to

facilitate rapid patient discharge after ambulatory surgery. For

example, a short procedure on the fifth finger can be performed using a

block of the ulnar nerve at the wrist. This technique is very quick to

perform, satisfies all surgical requirements, provides effective

postoperative analgesia, and allows the preservation of motor function

not only of the thumb, index finger, and middle finger, but also of the

fourth and fifth fingers. This chapter focuses on providing some

rationales for choosing the most appropriate strategy for anesthesia

and postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing upper extremity

surgery.

innervation is essential to define the minimum anesthetic and analgesic

requirements for a given indication, even if a more global approach is

chosen because of other considerations (i.e., the anesthesiologist’s

experience and the length of surgery), and even if ultimately the

surgeon determines the technique. For example, a median, ulnar, and

lateral cutaneous nerve block at the wrist represents the minimum

requirement for anesthesia for carpal tunnel release, even if an

axillary block is often performed.

|

Table 5-1. Most Common Anastomoses Between the Brachial Plexus Nerves

|

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

role of anatomy in performing a peripheral block of the upper

extremity: the level at which the nerves branch, anastomosis between

nerves, and global innervation.

branch and a motor branch below the axilla, with a number of

collaterals. For example, the radial nerve divides into a sensory and

motor branch above the elbow crease, with the sensory branch running

more superficially. The median and ulnar nerve divide into a sensory

and motor branch above the wrist, whereas the musculocutaneous nerve

supplies a motor branch to the biceps muscle and remains sensory

thereafter. Consequently, a radial nerve block performed in the axilla

results in a sensory and motor block of the posterolateral aspect of

the forearm. In contrast, when the radial nerve is blocked at the elbow

and below, the nerve has already divided into motor and sensory

branches. Therefore, it is important to block the radial nerve 2 to 3

cm above the elbow crease, especially when using a nerve stimulation

technique. The same is true when blocking the median nerve at the

wrist: The motor and sensory fibers are distinctly separated. In

addition, at the wrist, the median and ulnar nerves provide collateral

sensory fibers to the anterior and medial aspects of the wrist,

respectively, which originate above the wrist. Consequently, blocking

these nerves at the level of the wrist crease produces only incomplete

blocks. Wrist blocks need to be performed at least 4 cm above the wrist

crease.

plexus is frequent and may explain, at least in part, individual

variations after a nerve block. To increase the reliability of the

block, it is necessary to take this factor into consideration,

especially when considering the use of specific distal blocks (see Table 5-1, which lists the most frequent nerve anastomoses).

innervation is based on superficial distribution, it is important to

recognize that the muscular and bone innervation is not strictly

superimposed (Fig. 5-1).

The only location at which a single nerve innervates all structures is

the lateral edge of the hand and the fifth finger, both of which are

innervated by the ulnar nerve. There are some significant differences

between the superficial, muscular, and skeletal innervations. These

differences must be taken into account in determining the most

appropriate block(s) for a specific surgical procedure. Thus, the

surgical exploration of a second interdigital wound requires radial and

median blocks, whereas an ulnar block is also necessary if interosseous

muscle exploration is indicated.

the level of the brachial plexus or the individual nerves. Approaches

to the brachial plexus include the interscalene, subclavicular,

infraclavicular,

and axillary blocks. Other blocks of the upper extremity are high

humeral, elbow, wrist, and digital blocks. Each injection site is

associated with a defined probability of achieving a complete block for

a given nerve. The orientation of the plexus vis-à-vis the injection

site is an important factor to take into consideration. Although

experience is an important determinant of success, the extent of the

sensory and motor blocks also depends on the site at which the block is

performed. To maximize the correlation between the block resulting from

the use of a given approach and the surgical requirements, it is

important to choose an approach with the highest probability of

producing a complete block in the surgical territory. This can only be

achieved by gaining experience in the different approaches. Finally,

when using peripheral nerve blocks as the main anesthesia technique, it

is also important to account for all surgical requirements, such as the

prevention of tourniquet pain, especially if the tourniquet is placed

at the level of the arm and the surgery lasts more than 30 minutes.

|

|

Figure 5-1. Upper extremity innervation.

|

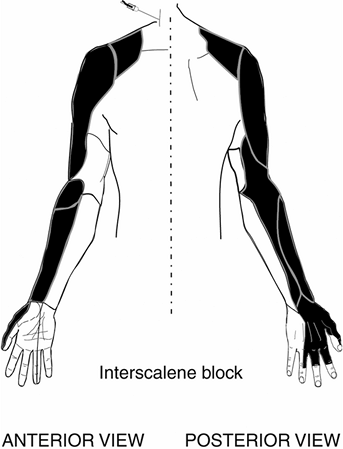

approached at the level of the trunks or roots. The anatomy of the

plexus relative to the site of injection with this approach explains

why the upper (C5-6) and middle (C7) trunks are preferentially blocked.

The lower trunk (C8-T1), which is more posterior, is often blocked

incompletely. Consequently, the shoulder and the lateral aspect of the

upper arm represent the territory with the highest probability of

block. In addition, the proximity of the phrenic nerve, the large

volume of local anesthetic usually injected (40 to 50 mL), and the

diffusion of the local anesthetic solution toward the cervical region

explain why the phrenic nerve, which runs anterior, is also almost

always blocked and why the sensory block may extend up to C2 (Fig. 5-2).

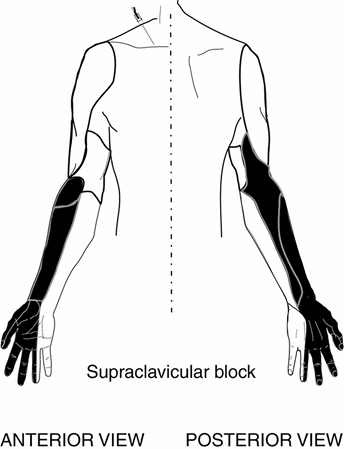

supraclavicular and infraclavicular approaches are associated with the

greatest diffusion of local anesthetic solution after a single

injection because, at these levels, the brachial plexus is the most

compact. However, supraclavicular injection preferentially blocks the

axillary, radial, and musculocutaneous nerves. Because at this level

the middle trunk is deeper, blockade of the median and, more

importantly, the ulnar nerves requires a longer onset time and is often

incomplete (Fig. 5-3).

|

|

Figure 5-2. Anterior and posterior view of an interscalene block.

|

|

|

Figure 5-3. Anterior and posterior view of a supraclavicular block.

|

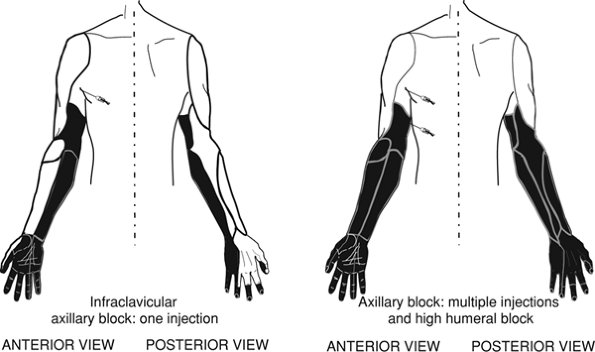

brachial plexus are individualized. As with the other sites, a single

injection does not produce complete upper limb anesthesia because (a)

the axillary and musculocutaneous nerves have already left the plexus

sheath, and (b) diffusion of the local anesthetic solution can be

incomplete. Although there is no anatomically defined separation

between the nerves, the presence of fibrous septa limits diffusion of

the local anesthetic solution. Therefore, it is difficult to achieve a

complete block with a single injection. However, the extent of the

block and the success rate can be increased by a multiple-injection

technique around the axillary artery (>90%). In this technique, the

use of a nerve stimulator greatly facilitates individual nerve

localization (Fig. 5-4).

|

|

Figure 5-4.

Anterior and posterior view of an axillary block using one injection and an anterior and posterior view of an axillary block using multiple injections. |

vasculonervous anatomic space exists only between the brachial artery

and the median nerve. The other nerves (i.e., radial, ulnar, and

musculocutaneous) are completely separated. Therefore, such an approach

allows each nerve to be blocked according to the surgical requirement.

In practice, the extent and success rate achieved with this approach

are comparable with those in a multiple-injection axillary block.

wrist, multiple injections are required. At the elbow, six nerves need

to be blocked. Three of these nerves are superficial (musculocutaneous,

posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm, and middle cutaneous of the

forearm) and three are deep (median, ulnar, and radial). At the wrist,

or more precisely, at the lower third of the forearm, eight nerves

provide innervation of the hand and the wrist. Four are superficial

(musculocutaneous, cutaneous middle of the forearm, superficial radial,

and posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm) and four are deep

(median, ulnar, anterior interosseous, and posterior interosseous). At

the wrist, the use of epinephrine solutions is contraindicated.

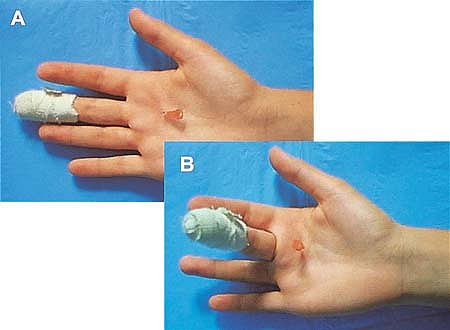

To be effective, it is necessary to block the dorsal and palmar

collateral nerves. The use of epinephrine solutions is contraindicated.

In addition, for the second, third, and fourth fingers, the palmar

collateral nerves provide innervation to the whole finger on the palmar

side and the first two phalanges on the dorsal side (Fig. 5-6).

An injection at or above the flexion tendon sheath facing the

metacarpophalangeal joint produces a block of the collateral palmar

nerves, thus providing anesthesia of three-fourths of the finger with a

single injection. The dorsal surface of the thumb is innervated by the

superficial radial

nerve,

which can be blocked through an injection in the flexor sheath. For the

fifth finger, an upper branch of the ulnar nerve innervates the entire

dorsal side. In this case, rather than two injections (one in the

sheath and one at the level of the ulnar upper branch), it is easier to

make a single injection and block the ulnar nerve 5 cm above the wrist.

|

|

Figure 5-5. Interdigital block.

|

|

|

Figure 5-6.

The palmar collateral nerves provide innervation to the whole finger on the palmar side and the first two phalanges on the dorsal side. |

established, the location, extent of the surgery, and expected

tourniquet duration guide the choice for the most appropriate technique.

shoulder surgery. It can be performed in the absence of general

contraindications, including (a) absolute contraindications (e.g.,

allergies to local anesthetics, infections at the injection site,

uncontrolled seizure disorder, major coagulation abnormality,

uncooperative patient); (b) relative contraindications (e.g.,

neurologic abnormalities in the territory affected by surgery); and (c)

specific contraindications (e.g., respiratory insufficiency). If the

surgical site also includes the supraclavicular region, a superficial

cervical plexus block is also required. Although interscalene block

alone is adequate for shoulder surgery, consideration should also be

given to its combination with general anesthesia, especially when the

surgery is expected to last for more than 2 hours. In these cases, the

block minimizes the requirement for opioids during surgery and the

immediate postoperative period. However, to minimize the risk for

complications (intravascular and epidural injections), it is highly

recommended that the block be performed before the induction of

anesthesia, while the patient is awake and under minimum sedation. If

the postoperative pain is expected to last more than 24 hours (rotator

cuff repair, total shoulder replacement, Bankart repair), the placement

of a catheter is indicated.

interscalene, supraclavicular, and infraclavicular blocks are equally

indicated for patients undergoing surgery below the shoulder and above

the elbow, the use of supraclavicular and infraclavicular blocks are

most likely to result in a higher success rate. However, the risk for

pneumothorax (immediate or delayed) represents a relative

contraindication of the supraclavicular block approach, especially for

ambulatory surgery. If prolonged postoperative pain control is

required, the placement of a catheter is indicated with an

infraclavicular approach.

high-humeral approach yield the best results for surgery at or below

the elbow. In contrast, interscalene blocks are not advised given their

insufficient extension in the C8–T1 territory. The use of a

supraclavicular block is possible, but the risk for pneumothorax needs

to be balanced against the specific benefit of such an approach. On the

other hand, the infraclavicular placement of a catheter for continuous

infusion may represent a viable alternative, especially in trauma cases

in which upper limb mobilization makes access difficult. Sometimes,

forearm surgery can also be performed with elbow blocks, allowing

anesthesia to be provided only to the surgical territory. This requires

an appropriate evaluation of the surgical field and knowledge of the

innervation, not only superficial but also muscular and skeletal.

However, the requirement for multiple injections may not always be well

tolerated by the patient.

performed initially at a higher level (interscalene, supraclavicular,

infraclavicular, axillary, and even high humeral).

for hand and wrist surgery. In addition, the use of a high-humeral

approach also allows the local anesthetic solution to be selected for

each nerve according to the surgical need. For example, 0.5% to 0.75%

ropivacaine may be used to block nerves directly involved with the

surgical territory for both anesthesia and immediate postoperative

analgesia, whereas 1.5% mepivacaine or lidocaine may be used to produce

a short-lasting sensory block to prevent tourniquet pain. This may also

limit the duration of the motor block while providing adequate

postoperative analgesia. Individual nerve blocks at the elbow and at

the wrist may also be indicated to complete a block in a specific

territory. Although these distal blocks have the reputation of being

more prone to inducing nerve damage, this has never been established.

|

Table 5-2. Most Common Upper Limb Procedures and Their Proposed Peripheral Blocks

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

consideration. First, the tourniquet can be placed at different levels:

arm, forearm, and even fingers. Tourniquets are usually well tolerated

by the patient as long as the inflation is not too high and they are

inflated for less than 30 minutes. After that, it is necessary to block

the patient accordingly. For example, a subcutaneous injection of

lidocaine 1% along the medial aspect of the arm to block the

intercostobrachial and medial cutaneous nerves of the arm may be used

to prevent pain from a tourniquet placed at the level of the arm.

outpatient procedures. In this environment, it is important to provide

adequate postsurgical analgesia even after discharge. This requires

educating the patient about the risks and symptoms of a persistent

sensory or motor block (e.g., vascular or nerve compression). An

alternative approach can be to perform a short-duration axillary block

using mepivacaine or lidocaine completed by either an elbow or wrist

block with ropivacaine for immediate postoperative analgesia.

fingers can be performed using a hyperselective technique at the wrist

(carpal tunnel release, trigger finger release, open

reduction,

and internal fixation of the fifth finger). These blocks are better

suited for ambulatory surgery. They preserve the mobility of the

fingers, allow early discharge, and are also better accepted by

patients. However, these blocks should be restricted to procedures

involving less than 20 to 30 minutes of tourniquet time, and they

require good cooperation among the patient, the anesthesiologist, and

the surgeon.