FLEXOR TENDON INJURIES: ACUTE REPAIR AND LATE RECONSTRUCTION

III – THE HAND > Conditions of Tendons > CHAPTER 48 – FLEXOR

TENDON INJURIES: ACUTE REPAIR AND LATE RECONSTRUCTION

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Virginia, and Alabama

Sports Medicine and Orthopaedic Center, Health South Medical Center,

Birmingham, Alabama 35205.

biomechanics of human flexor tendons are beyond the scope of this

chapter, the recent works of Gelberman and Manske (17,18), Manske and Lesker (19), and Brand (3)

form the basis of present approaches to flexor tendon repair technique.

Within the past 20 years, this knowledge has changed most of the

principles and techniques of flexor tendon surgery and—with the

enthusiasm for replantation—the timing as well. The importance that

each surgeon attributes to the blood supply will determine the

following:

-

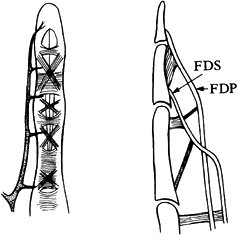

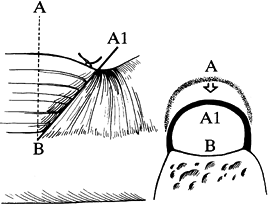

Whether a midlateral incision is used for exposure, which to some extent decreases blood supply to the tendon from that side (Fig. 48.1).

Figure 48.1.

Figure 48.1.

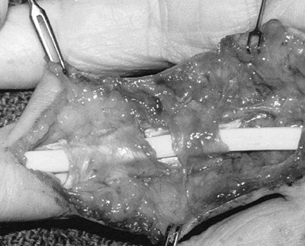

Segmental blood supply to digital theca. FDS, flexor digitorum

superficialis; FDP, flexor digitorum profundus. (Modified from Leddy

JP. Flexor Tendons—Acute Injuries. In: Green DP, ed. Operative Hand Surgery. New York: Churchill-Livingstone, 1982;1350.) -

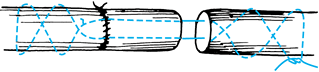

Whether a superficialis tendon, which has vascular interconnections with the profundus, is excised (Fig. 48.2).

![]() Figure 48.2. Vinculae to digital flexors.

Figure 48.2. Vinculae to digital flexors. -

Whether “strangulating” criss-cross

suture techniques (e.g., Bunnell) are used or sutures are placed more

palmarward to avoid disrupting the blood supply entering from and

residing in the dorsal aspect of the tendon. -

Whether closure or reconstruction of the sheath is necessary to enhance intrinsic healing and the synovial fluid environment.

-

Whether the effects of motion on tendon healing and strength determine the rehabilitation plan (8).Acknowledged important principles include:

-

A clean surgical wound is essential.

-

One wound and one scar enhance outcomes.

-

A poorer prognosis for function occurs with more damaged structures.

-

A mature wound is better for tendon repair and reconstruction (2,22).

-

Meticulous repair of all structures with stable bone fixation techniques permits immediate motion.

-

In repair of the periosteum or the dorsal

portion of the flexor sheath or pulley system, an interposing tissue

minimizes adhesions. -

Repair of vessels is important to nerve regeneration.

-

Repair of nerves is ideal for rehabilitation.

-

Repair of tendons is necessary to prevent

myostatic contracture and to allow rapid restoration of function, using

a controlled rehabilitation plan.

a tendon when the wound is initially debrided—during the “golden

period” of the first 6 hours after injury, when it can be assumed that

the wound has not been sufficiently colonized with bacteria to prevent

closure. However, some fresh wounds are so grossly contaminated

primarily that there is no golden period.

might be deferred in favor of initial debridement only. If a digit is

revascularized or replanted 6 hours after injury, and tendon repair is

also carried out, this is also considered a primary repair.

occurs when the initial wound is washed and debrided but tendon repair

is delayed for 2 to 14 days when the wound is not yet fully healed.

because myostatic contracture is not well enough established to prevent

“primary” end-to-end repair of the flexor tendon without having to

resort to secondary reconstruction (i.e., grafting) (25).

admonitions about problems with flexor tendon repairs in the pulley

area of the digital theca (the “zone of the pulleys” or Bunnell’s

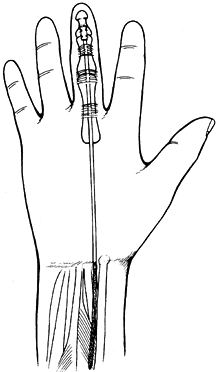

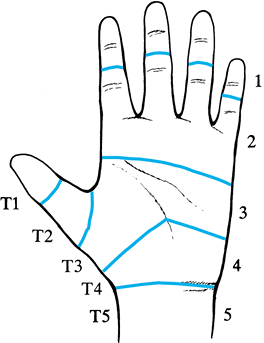

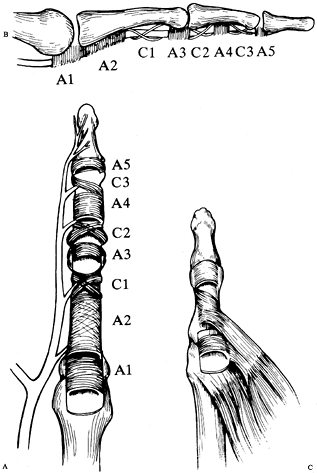

“no-man’s land”), Verdan (32,33 and 34) classified flexor tendon injury sites into five zones, each with its peculiar anatomy and prognosis (Fig. 48.3). Doyle redefined the pulley zones of the digit and thumb (Fig. 48.4); this classification is now generally accepted (5,6).

|

|

Figure 48.3. Verdan’s thumb and digital zones (modified).

|

|

|

Figure 48.4. Digital and thumb pulley systems as described by Doyle and Strauch. A,B: Digital. C:

Thumb (note annular pulleys at the metacarpophalangeal and just proximal to the interphalangeal joint with oblique pulley over proximal phalanx). (C modified from Doyle JR, Blythe WF. Anatomy of the Flexor Tendon Sheath and Pulleys of the Thumb. J Hand Surg 1977;2:150.) |

or forearm proximal to the carpal tunnel, which begins at the distal

palmar wrist crease (surface marking) or the proximal edge of the deep

transverse carpal ligament, extending from the trapezium to the hook of

the hamate. The site of the tendon injury is what defines the zone, not

the

site of the skin lacerations. The tendon injury site is the position of

the tendon with the wrist in neutral and the fingers in full extension,

although more properly the fingers should be in their resting position

of normal muscle tension or digital stance. As the fingers and wrist

move into flexion, as the flexor muscles contract, the tendon moves

proximally. Therefore, if the injury occurred at the wrist level but

the finger or wrist or both were flexed, the tendon injury occurs more

distally on the tendon (possibly in the carpal tunnel) when it resumes

its neutral or more extended position.

Verdan’s zone 5. The musculotendinous junction area may be involved.

Injuries can occur to the two wrist flexors, the palmaris longus, the

median and ulnar nerves (and branches), the radial and ulnar arteries,

and the nine flexor tendons of the digits and thumb. Multiple tendons

and muscles may be injured. The prognosis for function, including

individual function, in this area is good. Repairs need not be as

meticulous as in other areas, but they still must be done well.

distal palmar wrist crease or the proximal end of the deep transverse

carpal ligament to its distal margin, as noted by the crossing of the

proximal superficial palmar arch, formed from the ulnar side by the

ulnar artery leaving the canal of Guyon. The surface determination of

the distal extent of the tunnel is made by extending a line across the

base of the palm from the palmar surface of the maximally extended

thumb. In this zone, the nine flexors are tightly packed with the

median nerve. Repairs must be meticulous, and results, especially for

independent function, are more problematic than in any other area

except the zone of the pulleys.

proximal end of the pulleys, which begin at the metacarpophalangeal

(MP) joints. Surface markings in the palm are the proximal palmar

crease for the index, about midway between the proximal and distal

crease for the long finger, and the distal palmar crease for the ring

and little fingers. In this zone, both the flexor digitorum

superficialis (FDS) and the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) are oval

tendons, and the lumbrical muscle originates from the FDP. The

lumbrical tendon runs in its own sheath or tunnel radial to the long

flexor. Although repairs in zone 3 generally have a good prognosis,

secondary reconstructive

procedures originating here should allow for problems with intrinsic imbalance and excessive lumbrical action.

concern and debate regarding aspects of tendon nutrition, healing,

repair methods, and rehabilitation. Even the extent of the zone is

argued. Investigators agree that the zone begins at the MP level

[Bunnell’s first pulley, Doyle’s first annular (A1)], but the distal

extent is not defined. For prognostic purposes, the zone ends at the

mid–middle phalanx, the site of Doyle’s C3 (third cruciate) pulley but

also the most distal extent of the superficialis slips’ insertion (Fig. 48.4).

Distal to this point only a one-tendon system, the profundus, exists,

but Strauch has described the A5 (fifth annular) pulley at the distal

interphalangeal (DIP) joint level (29). Zone 2

is peculiar in that actually three tendons (profundus and two slips of

the superficialis) exist here in very close proximity; they are

surrounded by the dense unyielding cover of a floor (dorsally) of bone,

periosteum, and fibrous sheath and by sides and a roof (palmarly) of

dense fibrous tissue, thicker even in the condensations of the annular

and cruciate pulleys and dorsally at the palmar plates. Within the

sheath and pulleys the tendons have an intrinsic blood supply as well

as that from the parietal tenosynovium surrounding the tendons.

the MP level to allow the profundus to pass through it. It then becomes

two flat, slightly concave tendons that lie dorsal to the profundus and

hug its sides and then join just proximal to the proximal

interphalangeal joint to form the chiasm of Camper. The flat united

tendinous structure then divides after the proximal interphalangeal

(PIP) joint to form two flat slips, which insert along the middle

phalanx to almost its midpoint.

many of the surgical and rehabilitation techniques discussed in this

chapter and are by no means routine.

edge of C3 pulley) and the insertion of the profundus. Excellent

technique is also required here, but with good conventional techniques

the prognosis for function is good.

occur less often here with only one tendon of relatively uniform size

and no intrinsics. These thumb flexor zones are listed below:

ligament at the MP joint and a long oblique pulley over three quarters

of the proximal phalanx with a second annular pulley distally.

interphalangeal joint, to the insertion of the flexor pollicis longus

(FPL) just distal to the interphalangeal joint.

flexor tendons. This implies a thorough wash and debridement of the

wound initially, with tendon repair at 48 to 96 hours. Initial care is

done on an outpatient basis in an adequate facility (usually the

operating room, but possibly an emergency department suite where

tourniquet control, anesthesia, and good sterility are available). The

patient is placed on the elective surgical schedule in a few days.

socially dictated, preempt this approach. An unreliable patient is

likely to be admitted and operated on at the next available elective

operating time after initial wound care. If the patient has been

referred from out of town with a day-old injury, surgery is done at the

next elective opportunity. Medical conditions indicating acute repair

include a zone 5 injury requiring the repair of multiple damaged

structures and the repair of muscle and tendons before muscle

retraction makes the surgery technically more difficult. Digits with

vascular impairment requiring revascularization or replantation are

also repaired acutely, as delay may endanger the viability of the digit

(see Chapter 34).

-

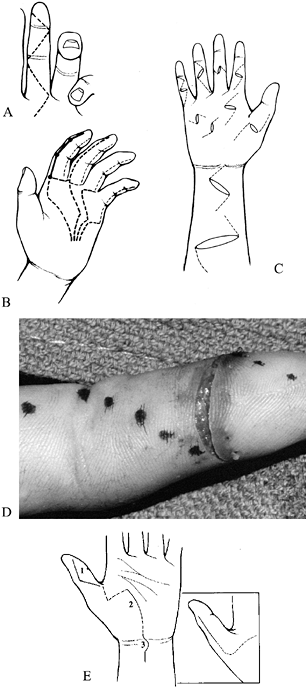

Begin by increasing the exposure

proximally and distally, converting the original laceration into part

of the zigzag Bruner approach (Fig. 48.5) (4). The history of the injury suggests whether the actual site of tendon laceration will be at the skin level or more distally. Figure 48.5. Incision options. A: The zigzag Bruner incision. B: Midlateral incisions. C: Extensions of lacerations. D: Extension of incision in clinical photo. E: Incision options for the thumb. (A,B modified from Schneider LH, Hunter JM. Flexor Tendons—Late Reconstruction. In: Green DP, ed. Operative Hand Surgery. New York: Churchill-Livingstone, 1982;1379. E modified from Urbaniak JR. Flexor Pollicis Longus Repair. Hand Clin 1985;1:72.)

Figure 48.5. Incision options. A: The zigzag Bruner incision. B: Midlateral incisions. C: Extensions of lacerations. D: Extension of incision in clinical photo. E: Incision options for the thumb. (A,B modified from Schneider LH, Hunter JM. Flexor Tendons—Late Reconstruction. In: Green DP, ed. Operative Hand Surgery. New York: Churchill-Livingstone, 1982;1379. E modified from Urbaniak JR. Flexor Pollicis Longus Repair. Hand Clin 1985;1:72.) -

Open the carpal tunnel area following the

thenar crease, but 1 to 2 cm distal to the wrist crease, direct the

incision ulnarly to the wrist crease, then change the direction sharply

and curve the incision proximally back to the midline. From here, each

zone is managed somewhat differently (see Chapter 37).

-

After extending the exposure, check each structure to verify the findings at physical examination. Check each

P.1475

structure for continuity and function. The profundi are aligned at the

same level just palmar to the pronator quadratus, with the index

profundus frequently independent. The flexor pollicis is more radial

yet and, although deeper, is just radial to the radial artery. The four

superficialis tendons line up, with the long and ring finger tendons

lying somewhat more superficially than the index and little finger

tendons, which lie to either side and more dorsal. The little finger

superficialis is closely associated with the ring finger tendon,

although slightly more dorsal. -

If the profundi and flexor pollicis

longus are intact, place an umbilical tape around them to avoid having

to recheck their identity repeatedly. Similarly, mark the intact

superficialis tendons and identify the more superficial wrist

flexors—the flexor carpi radialis (FCR) and ulnaris (FCU)—and tag the

median nerve with a vessel loop. Although any flexor motor can power

any distal tendon, it is best to match the lacerated components because

their lengths when repaired end to end should provide the appropriate

tension. This is particularly important for the profundi. Because of

their intimate interconnection, restoring tendon length is important to

prevent the short tether syndrome (quadriga).

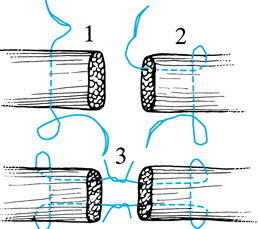

location, and appearance—that is, it does what it is supposed to do,

lies where it is supposed to lie, and looks the way it is supposed to

look. The preferred end-to-end tendon repair is the Tajima modification

of the four-corner grabbing stitch of Kessler (Fig. 48.6) (30).

Use two double-armed 3-0 or 4-0 monofilament polypropylene sutures with

pointed tendon needles. (For a discussion of recently advocated

multistrand techniques, see Chapter 47 by

Manske, particularly zone 2 repairs.) The multistrand repairs, although

more technically demanding, have experimentally demonstrated greater

strength, allowing more

active motion in postoperative rehabilitation, and may supersede the Kessler modifications in common usage (10,24,26,27,29,35,36 and 37).

|

|

Figure 48.6. The Tajima modification of the Kessler suture technique.

|

-

Pass the suture transversely through the

tendon about 1 cm behind the cut edge, which is minimally trimmed with

curved Stephen scissors. Then reinsert each needle just behind the

transverse suture and direct it on its side to the open end. Hold the

tendon at its cut end with a Beasley-Babcock forceps. This technique is

preferred to the conventional or modified Kessler, as the needles are

not directed into the cut tendon ends, which seems to create fraying. -

Use a separate double-ended suture for

each end. Once the sutures have been placed, cut the needles off, have

the assistant hold tension on the two strands on that side, and tie the

sutures on your side with a square knot, with a few additional ties. -

While the assistant holds the tied

suture, take up the slack on the untied side, just bringing the ends

together, and tie the second side. In zone 5, additional tidying

sutures are usually not necessary. Occasionally, a horizontal mattress

stitch with 6-0 nylon or polypropylene might be used to tuck in an

irregular edge. -

Use a combination of horizontal mattress

and locking horizontal mattress sutures for muscle repair. In the

locking stitch, instead of tying the two ends of the suture in the

conventional manner, make one or two throws on the needle end of the

suture, then place the needle-holder tip through the loop end of the

stitch, grasping the loose end on the far side and pulling it through

the loop (Fig. 48.7). This maneuver not only

creates the stitch tension away from the wound edge and everts the

edges but also approximates the edges and prevents excessive eversion.

This technique is also applicable in all tendon repairs where a

horizontal mattress suture might be used (e.g., superficialis slips,

chiasm of Camper), but excessive eversion is undesirable. Figure 48.7. The locking horizontal mattress stitch for “flat” tendons.

Figure 48.7. The locking horizontal mattress stitch for “flat” tendons.

-

After tying the Tajima sutures, do not

cut the two tied suture ends. Leave them inside the tendon initially.

Have the assistant hold the long ends and place a horizontal mattress

or locking horizontal mattress stitch with 6-0 nylon in the outer layer

of the tendon. -

Begin the circumferential running stitch

away from your side with the tendon flipped over (i.e., on the dorsal

or back side). Take the stitches toward yourself, return the tendon to

the palmar side, and complete the suturing, tying finally to the

initial stitch end. -

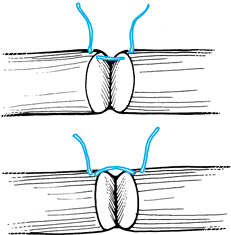

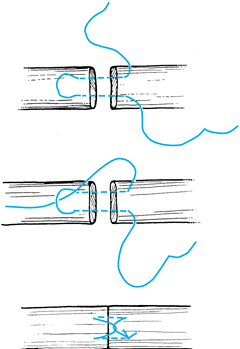

Although simple bites (1 mm or so from

the cut edge) are often satisfactory, invert these edges or at least

make them even. To invert, take each stitch just behind the cut edge (Fig. 48.8), which rolls in the edge, leaving a repair without pouting edges. Healing is not adversely affected.![]() Figure 48.8. Running stitch options at cut edge. The technique, depicted in the lower picture, slightly inverts the ends.

Figure 48.8. Running stitch options at cut edge. The technique, depicted in the lower picture, slightly inverts the ends. -

After the repair of the structures in the

carpal tunnel, begin rehabilitation, either with the wrist in neutral

or dorsiflexion to prevent palmar subluxation of the contents of the

tunnel. -

Because it is preferable to flex the

wrist up to 30°, we prefer to repair the transverse carpal ligament.

Direct suture is not usually feasible; zigzag cuts on opening the

carpal ligament risk damage to the palmar cutaneous branch of the

median nerve, which may run through the ligament, or to the motor

branch of the median nerve. Consequently, we close the tunnel somewhat

P.1477

more

loosely than its original ligament width by lacing it with a strip of

tendon like a shoelace (usually using palmaris longus, but occasionally

with a sagittal strip of FCR or an accessory tendon).

lumbrical may be repaired, but if it is damaged in its muscle

substance, it is probably better to excise it rather than to risk an

imbalance caused by intrinsic contracture. Repair both the

superficialis and profundus if they are lacerated, and also repair a

single tendon laceration. Restoration of digital strength and total

function requires both tendons.

-

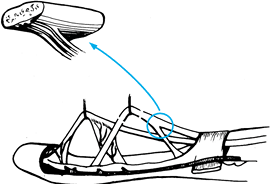

Extend the wound into a zigzag or Bruner incision (Fig. 48.5). Expose the sheath and open it along the side to create a funnel, as described by Lister (Fig. 48.9) (15).

Figure 48.9. Lister’s technique of opening the sheath to form a funnel.

Figure 48.9. Lister’s technique of opening the sheath to form a funnel. -

The side cut joins the transverse wound

in the sheath. If the tendon is sited proximally, make a second

incision more proximally, a mirror image of the first. The distal

tendon can usually be easily exposed in this manner, assisted by

flexion of the distal joints. If the proximal end is not held by a

vincula, or if the profundus alone is cut and not trapped at the MP

level where it passes through the superficialis, it is in the palm,

held by the lumbrical. Fishing for the proximal end with grasping-type

instruments is dangerous to the tendon, the bed, and proximally to

blood vessels and nerves. If the proximal end cannot be kneaded and

milked into the wound and then grasped with a mosquito hemostat in its

cut end, make a proximal incision and find it. -

Pass a pediatric rubber feeding tube or a

silicone-dacron tendon rod distally to proximally through the sheath,

suture the tendon with a single nylon suture through the cut end to the

eyelet in the tubing or to the rod, and draw it back into the distal

wound. -

When both tendons are cut, bring them

together distally. Bring the profundus through the superficialis, in

the normal anatomic position. If a problem arises passing it through

the sheath, open the intervening skin bridge and create another sheath

incision. -

Once the tendon (or tendons) is returned to the distal area, close the sheath opening with 6-0 nylon.

-

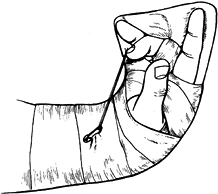

When the tendons are brought into the

distal wound, hold them in that position by skewering them with a

milliner’s needle that passes through the sheath and the tendons

proximally. Avoid the neurovascular bundles by placing the needle more

palmarly. Keith needles have a cutting edge and are less desirable than

the pointed milliner’s variety. -

Except at the open end, where the tendon

may be handled with the Beasley-Babcock forceps, handle the tendon with

the thumb and index fingers with an interposed moist sponge. -

Repair the superficialis slips or chiasm

with horizontal mattress sutures or locking stitches, using 4-0 nylon.

Collagen suture creates more reaction and is not advocated.

Polypropylene is satisfactory; braided polyester sutures do not slide

well and are no longer preferred by us. Braided nylon has also been

satisfactory, but monofilament nylon and polypropylene are preferred. -

Repair the profundus tendon with the

Tajima technique with 3-0 or 4-0 nylon or polypropylene, with the cut

edge repaired with a running stitch. If there has been damage to the

periosteum under the tendons, repair it with 6-0 nylon. If it cannot be

repaired, a graft of antebrachial fascia may be sutured in place as an

interposing membrane. Fractures are repaired before tendons, of course,

but if neurovascular repairs are indicated, particularly with an intact

skeleton, it may be technically easier to retrieve tendons into the

wound and place the Tajima sutures into the tendon but not tie them so

that the neurovascular repair under the microscope can be done on a

flat (unflexed) digit. -

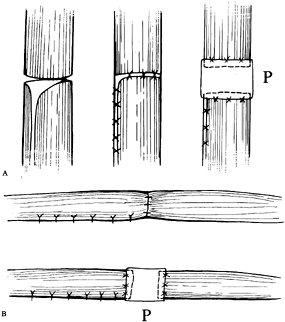

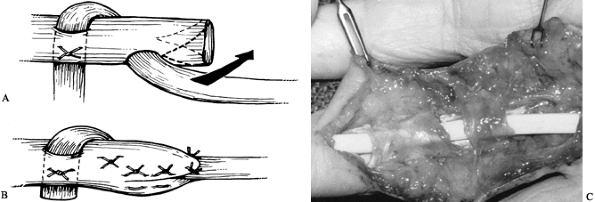

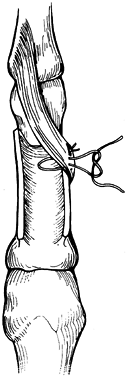

After the tendons are repaired, repair the sheath with 6-0 nylon (Fig. 48.10).

Leaving a gap in the sheath may result in sagging of the edge of the

sheath as the tendon attempts to pass through it, decreasing the

vertical diameter and trapping the tendon (Fig. 48.11).

Use simple or horizontal mattress sutures to repair the sheath. If a

gap remains, fill it by sewing antebrachial fascia to and over the

underlying sheath (Fig. 48.10). If a pulley is missing, reconstruct it, as described below.![]() Figure 48.10. Closure and reconstruction of the tendon sheath. A: Anteroposterior view of the sheath demonstrating direct repair and antebrachial fascial graft (P). B: Lateral view of repair and graft (P).

Figure 48.10. Closure and reconstruction of the tendon sheath. A: Anteroposterior view of the sheath demonstrating direct repair and antebrachial fascial graft (P). B: Lateral view of repair and graft (P). Figure 48.11. Buckling of the unrepaired sheath as the tendon attempts to pass through. Note loss of height of pulley (A–B to A1–B).

Figure 48.11. Buckling of the unrepaired sheath as the tendon attempts to pass through. Note loss of height of pulley (A–B to A1–B).

Also reconstruct the sheath. Full flexion of the digit to the distal

palmar crease usually requires A5 pulley preservation or

reconstruction. When the sheath is cut away, a sagging effect occurs as

the tendon moves proximally into the sheath, blocking full motion.

Advancement of the profundus tendon under the distal stump for a

reinsertion into bone rather than a tendon repair is not recommended:

the short-tether or quadriga effect may occur with this

maneuver, with loss of full flexion of the adjacent digits (33).

This technique can generally be used safely with the index finger

because of its usual independence from the other profundi. Advancement

still creates slack in the lumbrical, however, which may weaken or

unbalance its action.

-

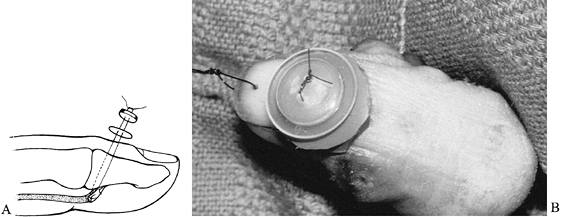

If the distal stump is short, take the

Tajima stitch proximally, then pass needles longitudinally through the

stump, then adjacent to the sides of the distal phalanx or through

drill holes (with a 0.045-in. pin) in the phalanx from palmar to

dorsal, emerging proximal to the germinal matrix of the nail bed. -

Tie the sutures over a dorsal button.

-

Place horizontal mattress sutures at the cut edge.

-

We have used small (or mini) suture

anchors for avulsions and short stumps in preference to dorsal buttons

in the last 3 years; 2-0 suture is used. We have had satisfactory

results, but the series is too small to advocate their use as yet.

|

|

Figure 48.12. A 90% partial tendon laceration.

|

-

The tendon may rupture if it is not repaired.

-

The tendon will be weakened if sutures are placed in it.

-

The unrepaired portion may not fully heal and cause triggering [catching on the edge of the fibrous sheath system (A1)].

less of the tendon’s cross-sectional area in zones 3 and 5 are best

left unrepaired. Repair lacerations of 50% with horizontal mattress or

locking-type stitches; lacerations of 75% or greater require full

repair. In zone 4, tidy up lacerations of 25% with debridement. In

zones 1 and 2, repair all partial lacerations; lacerations of 25% are

repaired with simple sutures. Use the “frayed tendon” rehabilitation

protocol postoperatively.

is missing, replace it with a segmental tendon graft (Fig. 48.13), using palmaris or a segment of flexor carpi radialis.

|

|

Figure 48.13. An intercalary graft repaired with a modified Bunnell suture technique.

|

-

Determine the length of graft needed by

applying traction on the distal segment to place the digit in its

normal stance position (Fig. 48.14). Then apply

traction to the proximal end. Maximum traction determines the extent of

the muscle’s elasticity; no traction is the zero-tension position. Some

50% to 60% of the maximal elasticity is close to the resting tension of

the muscle, which is the desired position.![]() Figure 48.14. The normal digital cascade or stance position.

Figure 48.14. The normal digital cascade or stance position. -

Take the amount of tendon graft and then

a bit more, to achieve the normal stance position, suture it in

tentatively, shorten it accordingly, and complete the suturing. -

This segmental interpositional graft

technique, frequently used for extensor tendons, is most applicable in

zone 5, is applicable with longer grafts in zone 4, and is possibly

applicable in zone 3. In zones 1 and 2, grafting of the entire distal

segment is more appropriate, as discussed below.

adequate for the minimally frayed tendon that is for the most part

intact. For severely “chewed-up” tendons, replacement is indicated. Use

segmental grafts in zones 3, 4, and 5. In zones 1 and 2, if the tendon

is badly damaged and hence irreparable but the bed is unharmed (not a

common occurrence), perform a one-stage graft, either primarily or as a

delayed procedure. Options are discussed in the section on grafting. If

the bed and tendon are damaged, perform two-stage grafting. Placement

of a tendon rod in the acute injury is questionable; we prefer to do

this in the clean wound at 10 to 14 days.

tendon transfer using the long or ring superficialis. When a lone

superficialis muscle is injured and is irreparable, we perform no

reconstruction. For multiple or massive injuries of the flexor tendons,

a transfer from the extensors may be indicated.

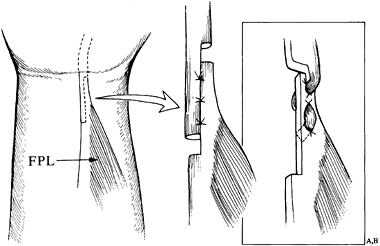

suture, advancement, or grafting, depending on the zone and surgeon’s

preference (see Fig. 48.5) (31).

Direct suture is used more often than not, but the usual independence

of the muscle/tendon unit (it is occasionally associated with the

profundus of the index) and the lack of lumbrical allow more repair

options.

bone insertion when the laceration has occurred within 1.2 cm from the

insertion (31). Between the MP joint and this

point, he advocates advancement with equivalent Z-lengthening at the

wrist, with and without reinforcing tendon grafting at the wrist (Fig. 48.15). Within the thenar zone, he prefers grafting. We have used these methods

successfully but usually prefer direct suture methods (30).

The technique and sheath repair methods are the same as in the digits.

While access to the thenar zone is difficult, the injury that exposed

and cut the tendon usually makes the access quite easy. If not, the

pediatric feeding-tube method to retrieve the proximal end and grafting

may be necessary. The carpal tunnel often must be opened to retrieve

the proximal end of the flexor pollicis longus. Direct suture methods

have been most successful in achieving full active motion, which is

represented by full extension of the thumb into the plane of the digits

and full flexion to the distal palmar crease of the little finger.

|

|

Figure 48.15.

Lengthening of the flexor pollicis longus at the wrist associated with distal advancement in thumb zone 2. Two methods of repair of the lengthening are depicted. (Modified from Urbaniak JR. Flexor Pollicis Longus Repair. Hand Clin 1985;1:73.) |

procedure, advocated for all injuries in zone 2, today it has only

occasional indications (2,34).

It is indicated when the damage to the tendons in zone 1 or 2 is

irreparable but the tendon bed is uninjured or minimally injured (Fig. 48.16). Prerequisites include a soft, pliable hand and digit with full passive motion of the joints.

|

|

Figure 48.16.

One-stage tendon grafting from the palm. More extensive pulley preservation is more common than the minimal number depicted. These three (with the proximal one somewhat closer to the metacarpophalangeal joint) are the most critical. |

-

Expose from the profundus insertion to

the palm, using a Bruner or midlateral incision, and extend into the

palm as a zigzag or sequential transverse incision (Fig. 48.5B). -

Classically, the tendon sheath is

partially excised, leaving only the three pulleys advocated by Bunnell.

Today, however, most of the pulley and tendon sheath system is

preserved, removing only enough to gain access to the remaining

portions of tendon. Proximally, leave the profundus in the palm short

enough so that it will not be drawn into the digital sheath when the

digits are in full extension. Leave the lumbrical origin, along with an

additional 1 to 2 cm. -

Distally, preserve a short stump of

profundus. Leave the distal portion of the superficialis (the chiasm of

Camper) and, if it is not already adhered, suture it to the sheath

proximally as a tenodesis to prevent hyperextension of the PIP joint. -

The usual source of tendon graft is the

palmaris longus. Take it through multiple transverse incisions in the

forearm, starting just proximal to the distal palmar wrist crease, and

remove it retrograde by passing a small hemostat from the proximal to

the distal wound. Alternately, we use the short forearm Brand tendon

stripper. Place it around the tendon distally and advance it into the

forearm while tension is maintained with a hemostat on the distal

divided tendon. The device then avulses the tendon at the

musculotendinous junction. Whether to remove paratenon or not is a moot

question. We remove all muscle and the bulk of the paratenon but do not

compulsively remove all of it. -

Distally, just under the profundus stump and distal to the insertion of the palmar plate of the DIP joint, drill a hole with a 5/64-in. bit just through the palmar cortex of the distal phalanx. This is distal to the epiphyseal plate in children.

-

Make two drill holes with an 0.045-in.

pin through the dorsal cortex on either side within the palmar cortical

hole. Pull the tendon through the digit from the tip to the palm, after

suturing it to either a reusable tendon rod or a pediatric feeding tube. -

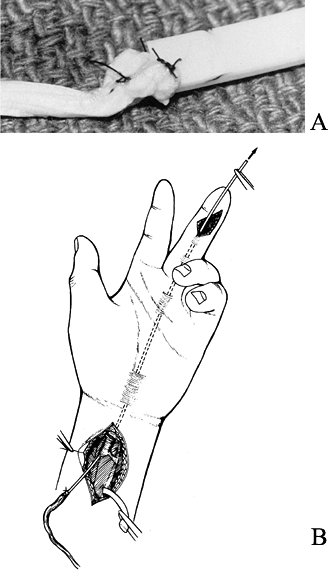

Make a Bunnell-type weave through the end of the tendon with 3-0 polypropylene on milliner’s needles (Fig. 48.17).

Figure 48.17. The modified Bunnell suture, similar to that advocated by Kleinert.

Figure 48.17. The modified Bunnell suture, similar to that advocated by Kleinert. -

Pass the two needles through the bone and

through dorsal skin proximal to the germinal matrix of the nail bed,

through a rubber button pad (made from medicine-jar stoppers or the

disposable irrigating syringe rubber bulb), and through the button.

Pull the tendon end into the hole in the distal phalanx and tie the

suture over the button (Fig. 48.18). When using a suture anchor,

P.1481

insert the anchor within the drill hole, to the side. Draw the tendon

into the drill hole as described but secure it by the sutures from the

suture anchor. Pull the polypropylene suture out distally.![]() Figure 48.18.

Figure 48.18.

The tendon graft is drawn into the palmar cortex with the suture tied

over the dorsal button and button pad. Note that the button suture is

placed proximal to the nail and germinal matrix. The graft is sutured

to the profundus stump as well. A: Artist’s drawing, lateral view. B: Clinical photograph of dorsal button. The suture has been placed through the nail for postoperative therapy. -

Suture the distal profundus stump down to

the graft with two to four simple sutures using 4-0 braided polyester

suture. Test the integrity of the button by gently attempting to lift

it away from the skin, to ensure that the sutures to the profundus

stump did not cut the polypropylene. -

Traction on the proximal tendon graft

should flex the digit to the distal palmar crease. If bowstringing

occurs, a pulley may need reconstruction. Then close the skin on the

digit. -

Although each step is important, this

next one is especially critical—setting the proper tension. Make a slit

in the distal end of the profundus stump in preparation for a

Pulvertaft interweave suture (Fig. 48.19). Pull

the motor tendon distally to 60% of its maximum elasticity and pull the

distal tendon graft through until the finger assumes a position

slightly more flexed than its normal digital stance. Note that each

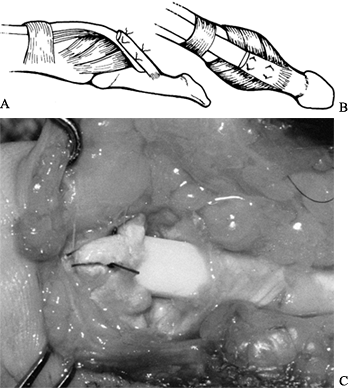

finger, from radial to ulnar, is slightly more flexed (Fig. 48.14). Figure 48.19. The Pulvertaft proximal interweave. A: The initial pass of the graft through the motor tendon. B:

Figure 48.19. The Pulvertaft proximal interweave. A: The initial pass of the graft through the motor tendon. B:

The motor tendon end is split and sutured around the graft. Two

additional passes are usually made through the motor tendon with the

openings made 90° to each other. C:

Clinical photograph of the proximal interweave. The motor end has not

been sewn over. (Modified from Schneider LH, Hunter JM. Flexor

Tendons—Late Reconstruction. In: Green DP, ed. Operative Hand Surgery. New York: Churchill-Livingstone, 1982;1387.) -

Using 4-0 braided polyester, suture the

graft and motor tendon together with a simple or horizontal mattress

suture. Then withdraw all support, place the wrist in neutral, and

observe the stance of the digit. If it assumes the desired posture, a

tenodesis effect is noted by flexing and extending the wrist. If the

digit moves appropriately with the other fingers and returns to the

proper position, the tension is correct; otherwise, tighten or loosen

it. -

When properly adjusted, make two

additional slits at 90° from each other and from the first slit and

complete the weave and suturing. Fold the distal end of the stump

around the graft (Fig. 48.19B). Making the

slits can be facilitated with a “tendon-braiding” forceps. Otherwise,

use a #11 blade or a #64 Beaver blade with a small hemostat placed

through the slit to pull through the tendon. Some surgeons wrap the

lumbrical muscle around this connection; we prefer not to disturb the

lumbrical. -

Close the incisions in the palm. When the

finger is sutured before the tension has been set, the zigzag wound is

more easily closed, the corner stitches fit more readily, and you need

not assume a contorted position to achieve closure.

graft (the sagittal section of the FCR, the superficialis of the little

finger, the proximal superficialis of the involved digit, and from the

leg the plantaris or toe extensors). An interesting technique known as

tenoplasty involves suturing the cut ends of the proximal profundus and

superficialis together at the time of the initial injury (20).

After a month, when this connection is healed, the proximal

superficialis is divided in the wrist, drawn into the palm, threaded

through the pulley system, and attached distally, thus requiring only

one connection in the second stage. However, we prefer palmaris or

plantaris as grafts because of their usual ease of harvesting and lack

of bulk. When they are not present, the alternatives are considered.

through bone onto nail or fingertip. When the tendon is brought through

the tip of the finger, the tension may be readily set distally, with

increased traction until the desired position is achieved. We prefer

our method described above, which creates fewer problems with nail

growth disturbance or irregularity in the digital pad contour.

on the concept that the first stage reconstructs the bed and the pulley

system, and the second replaces the tendon (11,25).

-

Place a silicone tube (Carroll) (1) or a silicone or silicone-dacron rod (Hunter-Swanson or Hunter) (11),

shaped like a tendon, into the digit, permitting a pseudosheath to form

around the rod. Fix the rod distally and leave it unattached

proximally, either at the palm or wrist level. We prefer the

silicone-dacron Hunter rod and discuss this method below. The first

stage of the procedure is usually performed under brachial plexus block

anesthesia. -

Expose the digit through an extended

Bruner incision from the profundus insertion to the palm and through a

curvilinear incision in the wrist. The exposure in the hand is the same

as in one-stage grafting. -

Preserve the distal profundus stump of

about 1.5 cm as well as the tenodesis effect of the distal end of the

superficialis. Preserve or rebuild the pulleys and carry exposure to

the palm. -

Remove other residual bits of tendon by

sharp excision with a Beaver blade (#64). Local scar tissue may be used

to fashion a tunnel where the old pulley system was once located (Fig. 48.20). Preserve or create pulleys at the base of the proximal phalanx, over the PIP joint, and in the mid–middle phalanx.![]() Figure 48.20.

Figure 48.20.

Clinical photograph of silicone-dacron tendon rod placed through

original tendon sheath and pulley system. Tunneling is also done

through healed scar. -

In the wrist, locate the profundus to the

involved digit, leave it attached distally to the lumbrical to maintain

its resting length, and tag it in the wrist with a colored suture. The

superficialis tendon is usually withdrawn into the wrist and excised;

sagittal strips of it may be used for pulley reconstruction. -

Apply distal traction to the profundus at

the wrist level to determine its elasticity, which should be equal to

that of the uninvolved adjacent profundus tendons. If it has lost its

elasticity because of severe myostatic contracture, the superficialis

is left adhered in the palm, tested, and, if adequate, tagged as the

future motor. If neither is adequate, choose and tag an adjacent

superficialis. -

Select a tendon rod of appropriate width;

usually a size 4 or 5 is correct for the digits, with the wider 5

needed for thumbs and the 3 for little fingers, smaller people, or

children. The rod should fill the proposed sheath but move easily

through it. It must also be large enough to create an adequate

pseudosheath for the future tendon graft. -

Maintain the rod under saline or

antibiotic solution in saline until usage to avoid lint accumulation.

Handle primarily with smooth instruments or wet gloves. Pass the

pointed end of the rod through the digital sheath from distal to

proximal to the palm level. Then pass a long hemostat or Kelly clamp

just palmar to the profundus and below the superficialis tendons

(dorsal to them) through the carpal tunnel (usually on the proposed

motor tendon) to the palm to the lumbrical level. -

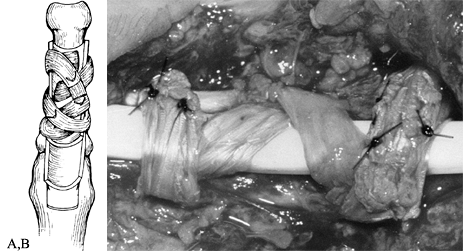

Grasp the rod and draw it into the wrist.

Distally, place the end of the rod snugly under the profundus stump and

suture it securely with four simple or horizontal mattress stitches of

braided polyester (Fig. 48.21). If a profundus

stump is unavailable, alternatives include suture to periosteum or use

of a special rod that has a screw attached that can be fixed to the

distal phalanx. Figure 48.21. The tendon rod is sutured under the old profundus stump. A: Lateral view. B: Anteroposterior view. C: Clinical photograph.

Figure 48.21. The tendon rod is sutured under the old profundus stump. A: Lateral view. B: Anteroposterior view. C: Clinical photograph. -

With traction applied to the rod, the

finger should flex to the distal palmar crease without bowstringing.

Using a large hemostat, open the space palmar to the profundi at the

distal forearm. The proximal end of the rod fits into this space (Fig. 48.22).![]() Figure 48.22.

Figure 48.22.

Tendon rod in first stage of two-stage tendon grafting. The tendon rod

is sewn under the profundus stump but lies free in the wrist, under the

superficialis and on the profundi. The proximal pulley is drawn

somewhat too distally. -

Test passive motion of the finger in full

flexion and extension to determine if there is any buckling in the

digit or the wrist. Extra length of rod in the wrist can be excised. In

the palm, a bridge or pulley can be loosened to prevent buckling or a

new pulley reconstructed. If buckling persists after skin closure,

erosion of the rod through the skin can occur.

during acute repair or one-stage grafting and in or after tenolysis.

Our preferred technique is that described by Kleinert and attributed to

Weilby (12). Other methods (for example, that of Lister) can also be used (14).

Use the residual base of the annular ligaments and underlying

periosteum, along with a long narrow strip of tendon. If superficialis

is used, create a sagittal strip about one-eighth the width of the

tendon, several inches long.

-

Make a slit through the remnant of the

annular ligament on either side of the rod using a #64 Beaver blade or

a #11 blade, and place the tips of a cardiovascular hemostat through

the slit to grasp the tendon. Draw the tendon over the rod and down

through the opposite slit. -

Make several more pairs of slits

distally. Criss-cross the tendon over the rod and through the slits,

like a shoelace through eyelets. -

Finally, cinch the lacing (pulley) tight

enough to eliminate bowstringing and yet loose enough to allow passage

of the rod during passive range of motion. -

Pass the tendon ends through themselves or through proximal criss-crosses and suture them.

through the slits (Fig. 48.23).

A simple pulley reconstruction, particularly applicable to the A3 area,

over the PIP joint, involves the use of one residual slip of

superficialis left attached distally, with the proximal end woven

through or sutured to the annular ligament remnant (Fig. 48.24).

|

|

Figure 48.23.

Building the pulley using the remnant of the old annular ligament system and a strip of tendon; method described by Kleinert and attributed to Weilby. A: Artist’s rendition. B: Clinical photograph of pulley built over a tendon rod. |

|

|

Figure 48.24.

Pulley built with remaining distal slip of superficialis, placed through and sutured to the remnant of the annular ligament. (Modified from Schneider LH, Hunter JM. Flexor Tendons—Late Reconstruction. In: Green DP, ed. Operative Hand Surgery. New York: Churchill-Livingstone, 1982;1425.) |

and forth with passive range of motion of the digit. This can be done

with passive range using the opposite hand to move the digit through

its range or by trapping the digit

using

adjacent fingers to draw it into flexion. The intact extensor mechanism

extends the digit. If a capsulectomy or use of an artificial joint

accompanied placement of the tendon rod, use dynamic splinting. This

may include a low-profile extensor-assist splint alternating with

flexor-assist rubber band or thread devices or individual spring-loaded

assistive joint extensors, flexors, and adjustable static devices. The

hand therapist plays a very significant role in helping the patient to

achieve a maximum range at this point. The maximum attainable range,

actively, after the second stage will be no more than that achieved

passively at this time.

to achieve a good pseudosheath, which is also soft, sheer, and

flexible. Do not maintain the rod in place beyond this time as it may

lead to a thicker, fibrous, less flexible pseudosheath with a poorer

result.

be certain that the distal end of the rod is in place, buckling is

absent, and the excursion of the rod is 1 cm or more. If these criteria

are not met, stage 1 may need to be revised. It is not unheard of for

the distal end of the rod to break loose and piston into the wrist (25).

Obtain anteroposterior and lateral views of the hand and forearm

(fingertips to midforearm) in full extension and full passive flexion

of the involved digit. To determine excursion, measure the proximal tip

of the rod from any fixed bony landmark. Assuming all is well, proceed

to stage 2.

range of motion. This is essential, however, so do not proceed without

it. Occasionally, an inflammatory reaction may occur because of the rod

or lint, and so on. Prescribe rest, immobilization, and antibiotics and

antiinflammatories for 10 to 14 days. If the problem resolves, resume

therapy. If not, consider reexploration, rod removal, and debridement.

If infection exists, use suction-irrigation and systemic antibiotics to

clear the digit and attempt rerodding later. Most attempts at repeat

tendon reconstruction are unsuccessful, however, and other approaches,

such as fusions or amputation, may be indicated. If only inflammation

occurs, it may be caused by lint contamination, and another attempt at

rodding is warranted.

straightforward for the experienced surgeon. Add the free tendon graft,

connecting it properly at either end. In fact, these steps are

identical to those used in one-stage grafting. Unfortunately, there are

pitfalls peculiar to this stage.

-

Perform the procedure under general

anesthesia with the arm and a leg prepped (usually the contralateral

leg, so a second team can take the plantaris tendon graft unencumbered). -

Locate the plantaris with a short

transverse incision made over the medial edge of the Achilles tendon,

about four fingerbreadths above the tip of the medial malleolus. If you

explore too distally, the tendon may have already fused with the

Achilles tendon or it may be located behind it. It is generally absent

or deficient about 14% of the time. Assuming it is present and not

hypoplastic, make a second, more distal incision, divide the tendon,

and withdraw it into the proximal wound. -

Split the fascia proximally and place the

ring of a Brand tendon stripper over the tendon, which is grasped

through the ring with a hemostat. -

With the leg straight and level (usually

resting on two folded towels), advance the stripper slowly with a

twisting motion of the fingertips while the tendon is held relatively

taut. There is one interval, as the stripper passes between the

gastrocnemius and the soleus, where progress is slow; be patient so

that you do not prematurely cut the tendon. -

Advance the stripper to the

musculotendinous junction, avulse the tendon, and deliver it. Debride

muscle and paratenon, but do not remove paratenon compulsively.

to use a toe extensor. If one is grafting for a little finger, only to

the superficialis insertion (see the discussion below on salvage), or

to a thumb, a palmaris may be long enough. It is easy enough, in the

absence of the plantaris, to take the palmaris, and measure it (on the

surface) before proceeding with the toe extensor, which is more

difficult to harvest and can result in more morbidity.

always present and are long enough. The extensor brevis substitutes for

the communis in the foot. The disadvantages are the interconnections

between the tendons under the extensor retinaculum and proximally,

which make it impossible to harvest a smooth, unblemished tendon, and

it takes time to deliver the specimen.

-

Begin with a transverse incision, just

proximal to the level of the metatarsophalangeal joint over the

prominent tendon. The fifth is not used, as there is no extensor

brevis. We find that the third and fourth usually are easiest to

harvest. -

Locate the extensor brevis tendon and

suture it to the longus, which is then divided proximally. With

traction on the cut end, identify the tendon proximally and make a

second transverse incision. -

With the fascia divided, pass a hemostat

distally over the exposed proximal tendon to the distal wound, where

the cut end is grasped and the tendon delivered retrograde into the

proximal wound. Continue proximally until an adequate length is

obtained. The maneuver is easy distally, but proximally the tendon must

be separated from its mates. This is done partly by peeling the tendon

from the others and partly by cutting with

P.1486

a scissors. Closer-interval incisions proximally will facilitate this activity. -

Apply a bulky elastic dressing to the leg and foot for about 2 weeks.

-

On the upper extremity, open the

curvilinear incision on the wrist, exposing the tagged motor tendon and

the proximal end of the rod. Again test the motor for elasticity;

another motor can still be used. -

Remove the pseudosheath from the end of

the rod and expose the incision over the distal end of the rod. We

prefer to open the old zigzag, as a midlateral in a scarred finger at

this point is more likely to injure digital nerve branches. Note the

sutures taken through the profundus stump; locate the proximal extent

of the stump and carefully lift the stump away from the underlying rod

as the sutures are cut. Do not damage the pseudosheath under the rod or

the palmar plate. -

A difference in the shade of the white

palmar plate and the more opalescent pseudosheath distally over the

bone should be apparent. Take the pseudosheath just distal to the plate

off the bone with a #64 Beaver blade and drill a hole with a 5/64-in.

bit through the palmar cortex (as with the one-stage graft). Make two

more holes on either side with 0.045-in. pins, from inside the hole

through the dorsal cortex, to emerge proximal to the nail and the

germinal matrix. -

Suture the tendon graft to the rod proximally and pull it through the pseudosheath (Fig. 48.25). If the tendon pulls free, simply reinsert the rod through the pseudosheath.

Figure 48.25.

Figure 48.25.

Stage-2 tendon grafting. The tendon graft is attached to the rod, which

is then drawn out of the hand distally, pulling the tendon through the

pseudosheath. A: Clinical photograph of tendon graft sutured to the rod. B: Illustration of graft about to be drawn into the hand. -

Place a hemostat on the proximal tendon

and place a weave stitch (usually a Bunnell type) through the distal

end with 3-0 polypropylene on milliner’s needles, which are then placed

through the drill holes to be tied over the dorsal button and button

pad (Fig. 48.18). Draw the tendon snugly into the bone before tying the suture. -

Secure the graft to the residual

profundus stump with safety stitches of 4-0 braided polyester suture.

With traction on the proximal tendon, the digit should fully flex or do

so to the extent achieved with passive motion. -

Release the motor tendon from its distal attachment at the wrist crease level.

-

Close the incision on the digit and

attach the graft to the motor tendon at the proper tension, using the

Pulvertaft interweave stitch (see one-stage graft technique

above). Again, this is achieved by making a slit in the motor tendon,

which has been pulled up to 60% of its elastic length, and pulling the

graft through until the digit assumes a position of flexion slightly

greater than the normal stance position relative to the other digits. -

After the first trial stitch, test the

position with the tenodesis maneuver, flexing and extending the wrist.

If the digit moves with the other fingers and then, with the wrist in

neutral, achieves the proper digital stance, make two additional slits

in the motor tendon and complete the interweave. -

Rehabilitation is described below.

Immobilize in a bulky dressing with the wrist flexed 30°, the MP joints

in 75° to 90° of flexion, and the interphalangeals toward extension

(the intrinsic-plus position). Apply the bulky dressing with a

posterior plaster splint above the elbow initially, to enforce

elevation.

the injury is unrecognized or the repair has ruptured, the surgeon may

be faced with a finger that functions well with full mobility at the MP

and PIP joints, but the tip of which is flail. The dilemma is whether

to maintain this full functional PIP motion, sacrificing DIP motion,

stabilizing the tip in some way, or to risk the excellent motion; that

is, compromise the superficialis’ full function for the sake of some

DIP control. Nongrafting measures are tenodesis or arthrodesis of the

DIP joint.

-

The potential problems with this stage of

the procedure include detachment of the graft proximally or distally or

both, rupture of the graft, adherence of the graft to the sheath, and a

flexion contracture of the DIP joint. -

To avoid rupture of the graft or pulling

out of the suture distally, take an adequate graft; do not accept a

graft of too-small diameter or one with iatrogenic defects. If the

graft is damaged or hypoplastic, take the time to harvest the toe

extensor. It is not worth the grief that results if this point is not

heeded. -

To confirm the integrity of the distal

polypropylene suture, test that the safety stitches have not cut it by

gently lifting the button, making sure it is springy, and applying

traction to the proximal tendon. Starting the polypropylene weave

distally no more than 1.0 to 1.5 cm from the end of the graft is

usually safe. The proximal attachment is usually safe with a three-slit

interweave. Adhesion in the sheath should not be a problem if the motor

muscle–tendon unit is elastic and has good excursion, the pseudosheath

is not thick and fibrous, and rehabilitation is appropriate. If the

proximal attachment is in the forearm and not the carpal tunnel, the

adhesions at this site can be worked out with activity. -

A flexion contracture at the DIP joint

remains an enigma. Avoiding iatrogenic damage to the palmar plate and

attending to the problem with therapy are obvious. Pseudosheath

contracture may be a factor. Two additional controllable factors may be

preserving the A5 pulley and placing the tendon insertion just distal

to the palmar plate, not further distal on the distal phalanx. -

With attention to all these factors,

flexion contracture still occurs in some patients, and although the

digit is functional, its appearance is compromised. An arthrodesis of

the DIP joint is the solution in severe cases

the DIP joint during pinch or grasp. In some cases, a tenodesis may

already exist from adherence of the distal profundus across the DIP

joint. It may be accomplished surgically by suturing the profundus

stump down to the sheath, residual annular ligament, and periosteum.

Pin the joint for 1 month and then mobilize. The position of

immobilization is in 5° to 10° of flexion for the digits and in 0° or

neutral for the interphalangeal joint of the thumb. Theoretically, the

digital interphalangeal joints should be increasingly flexed across the

hand from radial to ulnar, allowing grip to the distal palmar crease.

In reality, this is unnecessary for strength if the joint is stable. A

flexed or a hooked finger is undesirable functionally and cosmetically.

and the further contraction of others. With these problems in mind, we

prefer arthrodesis, which can be done in a variety of ways.

digit, where the superficialis is often smaller than normal and may be

deficient. It may also rupture if sufficient stress is placed on it (we

once observed a rupture 30 years after the profundus injury).

Otherwise, the decision to graft is made after considerable discussion

with the patient concerning the potential benefits and risks. Grafting

is most applicable in young patients. If the digit is mobile, a

one-stage graft is a consideration. A two-stage procedure is more risky

for the superficialis, but it is indicated if there is distal bed

damage. Goldner has recommended that neither the graft nor the rod

should be placed through the split in the superficialis but rather

placed alongside in the sheath (9). Of course,

the sheath may have contracted around a single tendon if the profundus

has retracted significantly. It is reasonable to suggest to the patient

that you will attempt to graft, but if the attempt appears more

formidable once the finger is explored, then distal stabilization will

be done instead.

ruptured, options of one- or two-stage grafting may also be considered.

If the muscle has lost its elasticity, a tendon transfer may also be

performed, either as one stage, if the bed and pulley system are good,

or two stages, through a pseudosheath. The usual motor is the

superficialis to the ring finger, although the long finger tendon is

equally acceptable. If two stages are planned, a large rod, either size

5

or 6, is needed and should be matched for size with the potential motor

in the first stage. No graft supplement is needed, as the tendon

reaches the distal phalanx easily. Also, with the flexor pollicis

brevis, and the adductor and abductor pollicis all acting to flex the

MP joint, arthrodesis of the interphalangeal joint can be considered.

The strength and normal function of the thumb are significantly aided

by a functioning FPL. The function of the intrinsics is not at

significant risk with grafting or transfer as with an intact

superficialis to a digit, so that interphalangeal fusion of the thumbs

is far less indicated. It is, however, an option, particularly when

there are multiple injuries and transfers and grafts are more important

elsewhere.

the passive range and it is determined that this is caused by tendon

adhesion or block. The extent of full motion required for functional

status depends on the patient’s actual requirements and wishes and a

realistic expectation of the results of surgery. A thumb, for example,

that can pinch well to all the digits, particularly to the index and

long fingers but does not flex to the distal palmar crease proximal to

the little finger is not disabled by most criteria. However, a digit

that does not flex to the palm and defunctionalizes all the others as

well (quadriga) is very disabling. The musician, specifically a string

player such as a violinist or cellist, may be significantly more

disabled than a keyboard player with the same loss of range. Therefore,

the decision to perform a tenolysis must be individualized.

mobilize a digit and for the tendon to be revascularized. Two

complications of tenolysis are failure to maintain gliding and rupture

of the repair. Premature tenolysis may well be the cause of the latter.

At least 4 months should elapse after repair before tenolysis to allow

adequate revascularization of the tendon so that it can tolerate the

procedure. The contraindication to tenolysis—too-extensive adhesions—is

discussed below.

results are directly proportional to the extent of the adhesions. If

there is a small “spot weld,” subsequent full function (to the extent

of the passive motion) may be anticipated. If the adhesions are

extensive and there will be multiple healing or raw areas, the

likelihood of success is nil. The amount of the initial trauma,

particularly the number of tissues injured (bone, sheath, tendon,

vessels, etc.) and the extent proximally and distally of damaged

structures, determines the density of the adhesions in many cases.

However, a simple tendon laceration, with or without infection, may

result in multiple adhesions for a considerable distance.

or if there is a history of infection and to use two-stage tendon

grafting (rod insertion) if the adhesions are extensive from trauma.

preferring the patient to begin active mobilization immediately. We

prefer to do the procedure under regional block. Therapy may be

initiated with the block still in effect, and continuous passive motion

seems to be helpful, particularly in controlling discomfort. Continuous

passive motion is especially indicated if capsulectomy is also

performed. Leaving an indwelling catheter in the palm around the

digital nerves, or around the median or ulnar nerve (if this is

adequate), for the injection of a long-acting anesthetic is a valuable

adjunct postoperatively.

adherent scar through generous incisions, as needed. The more incisions

needed, the more postoperative scarring, of course. If pulleys need to

be removed, they must be rebuilt. Usually tenolysis is first performed,

the digit rehabilitated, and then the pulley rebuilt to eliminate the

unsightly, uncomfortable bowstringing in a later operation. Using the

surgical technique described earlier for constructing pulleys,

immediate construction can be undertaken.

-

Investigate the site of the initial

trauma or surgery, extending in either direction to open the sheath and

determine whether the tendon is free. Remove adherent sheath, using a

Beaver knife blade and Penfield elevators (usually #4) for the

dissection. -

If the release seems sufficient,

particularly if the digit only is involved, make an additional incision

in the palm at the lumbrical level and apply traction to pull the

tendons proximally. If motion is full with each tendon, apply traction

distally to ensure the tendons glide well through the carpal tunnel. -

At the completion of the procedure, place an indwelling catheter in the hand or wrist for postoperative local anesthesia.

tendon repair include the potential for rupture, adherence of the

tendon to surrounding tissues, and joint contractures. Philosophies of

postoperative management vary along a continuum from 3 to 4 weeks of

complete immobilization, with the intent of minimizing the risk of

rupture, to very early protected active mobilization, with emphasis on

minimizing tendon adherence and joint contracture. Although controlled

clinical studies are few, recent research

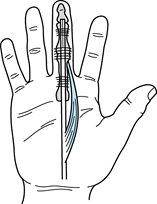

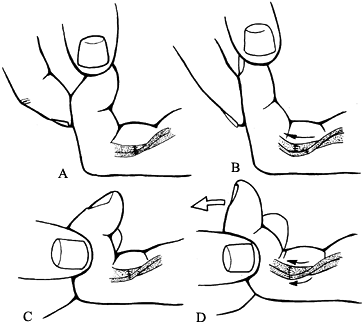

definitely lends support to the concept of at least early passive mobilization (Fig. 48.26) (7,8,16).

|

|

Figure 48.26. Postoperative passive motion regimen described by Duran. A,B:

With the proximal interphalangeal joint maintained in a flexed position, the distal interphalangeal joint is flexed and fully extended. C,D: With the distal interphalangeal joint maintained in flexed position, the proximal interphalangeal joint is carefully exercised. Both activities create gentle passive motion of tendons, promoting both strong healing and gliding. |

best method of management for each patient. The degree of trauma and

surgical technique will influence the strength of the repair and the

degree of scarring. The experience and skill of the therapist are

critical factors in the delicate balance between protection and

mobilization during the early postoperative weeks. Consider the

patient’s behavior, attitude, and intelligence in terms of his or her

ability to comprehend and implement instructions, degree of motivation,

reliability, and availability for follow-up. Currently we use an early

protected motion program.

greater in zones 2 and 4, where there is less yielding adjacent tissue

and more confined space, early protected motion management is used for

all zones.

flexion and the MP joints in 70° to 90° flexion. Allow full active

interphalangeal extension. Elevate the extremity to control edema.

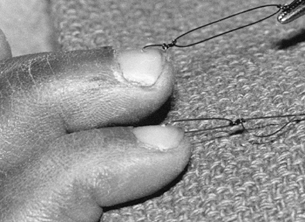

time of surgery and proximally about 8 cm proximal to the palmar wrist

crease. Tension should be adjusted to maintain the involved digits in a

flexed position at rest yet allow full active interphalangeal extension

(Fig. 48.27).

|

|

Figure 48.27. Suture loops through nails for postoperative controlled passive motion method of Kleinert.

|

interphalangeal joint fully 5 to 10 times every hour. If extension is

difficult or painful, the patient may need to pull the traction

distally with the other hand while extending to facilitate full active

extension, then release slowly to return the finger passively to the

flexed position.

-

No nail suture or loss of nail suture.

-

Pain or apprehension limiting full, active interphalangeal extension.

-

Inadequate fit of bulky dressing, allowing some MP extension as the patient attempts to extend the interphalangeals.

-

Swelling, relieved by elevation and use of a compression wrap.

-

Interphalangeal flexion contractures.

light dressing. Place it in a thermoplastic splint with dorsal

extension to the fingertips and joint positions maintained. Add a

palmar piece to contour the palmar arch, ensuring stable positioning of

the dorsum of the hand in the splint. Otherwise, the splint may tend to

slip, and as the patient extends the interphalangeal joints, the dorsum

of the hand may pull away from the splint, resulting in MP extension

rather than full interphalangeal extension. Use Velfoam straps (2-inch)

to the forearm and wrist, with a 1-inch

strap

across the palmar piece if necessary. Attach a pulley to the palmar

piece. Attach nylon cord to the nail suture, run it through the pulley,

and attach it to elastic traction. Attach the elastic to a safety pin

on the proximal splint strap. The nylon should be just long enough so

that the elastic does not catch on the pulley during active extension (Fig. 48.28).

|

|

Figure 48.28.

Postoperative controlled passive motion thermoplastic splint with elastic traction. The splint maintains the metacarpophalangeal joint in flexion while allowing full extension of proximal interphalangeals against the elastic band. |

wraps for the hand and digits if necessary to control edema. Continue

the same exercises, with emphasis on full interphalangeal extension.

Manage early flexion contractures with careful, gentle assistive

extension of the involved joint with the proximal and distal joints

flexed. See the patient twice a week if possible to ensure maintenance

of positioning and good progress. This stage may be delayed at the

discretion of the surgeon if there is excessive trauma or a tenuous

repair.

Continue traction and the exercise program, adding an active flexion

hold after the digit is passively flexed fully five times per hour.

This step requires maximum tendon excursion without maximum tensile

loading that results with active flexion from the fully extended

position.

joints are noted, discontinue elastic traction at night and use a

static extension strap to the dorsal extension of the splint, extending

the PIP only. A static aluminum splint may be used for the PIP or DIP,

but it must be directed to one joint only to avoid tendon tension.

because of the level of injury, maintain the wrist at 30° flexion and

increase MP extension to 40° to 45°.

changes with the surgeon if any question exists about the status of the

patient. Very free joint mobility and tendon excursion may indicate

minimal scarring, but the tendon may be more vulnerable to rupture.

cuff. Allow full active wrist and digit motion, but with protection

from full tendon tension because of a tenodesis effect. Begin joint

blocking with the wrist and MP joints in neutral, along with full

active flexion from the extended position, 10 times per hour. Dynamic

flexion splinting can be added if necessary. Static individual joint

extension splinting with the adjacent joints neutral or flexed may be

indicated by lack of progress with active and assistive exercise alone.

presence of MP or interphalangeal flexion contractures, continue

neutral wrist splinting without traction. Remove the splint for

exercise.

weeks, but the wrist and digits may be extended simultaneously. Add

individual dynamic joint extension splinting, if indicated, with the

wrist neutral.

if necessary. Add graded resistive exercise and activity at 10 weeks.

By 12 weeks the patient may return to full activity.

repairs of the thumb is similar to that of the fingers, with the

following exceptions:

-

The wrist is flexed 30° to 35°.

-

The thumb carpometacarpal joint is held in palmar abduction.

-

The MP joint is in flexion, with elastic

traction attached to the nail via a nylon cord run through the same

type of palmar pulley as described for the fingers.

joint blocking and opposition exercises, full tendon excursion is

encouraged by full active extension of the carpometacarpal, MP, and

interphalangeal, followed by flexion of the thumb toward the base of

the little finger.

weeks against attempted use of the uninvolved digits, as contraction of

the FDS and FDP, particularly against resistance,

may

stress the repaired tendon. Close follow-up is essential for success.

If positioning is lost, exercise techniques are incorrect, or

adjustments are not made for impending contractures, the results will

not be optimal.

degree of excursion of the lysed tendon achieved at surgery. Consider

carefully all factors pertaining to each patient’s clinical situation,

including the patient’s history, previous surgery, and preoperative

status, the condition of the tendon, and the status of the pulley

system. Excessive edema or pain, diminished vascularity from previous

injury or surgery, previous infections, and poor tendon quality and

pulley reconstruction are all factors that may require modification of

postoperative care to achieve the maximum potential without

complications.

Xeroform (Sherwood Medical, St. Louis, MO) and 4-inch stretch gauze

bandages, using sterile technique. For pain control use TENS or an

indwelling catheter with a 0.5% bupivacaine (Marcaine) injection before

therapy. Control edema with elevation and a compression wrap if

necessary.

isolate the flexor digitorum profundus and flexor digitorum

superficialis 10 times each hour. Also with the wrist neutral,

passively flex the involved digits, then ask the patient to actively

maintain the position. Remove the passive force while the patient

continues to hold. This is followed with active extension, and the

patient repeats the exercise 10 times hourly. This requires maximum

flexor and extensor excursion while reducing tensile loading of the

lysed tendon.

encourage exercise despite pain, with the goal of an active range of

motion that is equal to the passive range. Achieving this goal within

the first 2 weeks is critical. Measure joint range of motion, total

active range of motion, and total passive motion twice weekly to

monitor progress objectively.

depending on the tendency toward joint stiffness or the difficulty the

patient has in initiating motion from either a flexed or extended

position. Dynamic or static flexion is indicated if there is difficulty

regaining preoperative passive flexion, or if active flexion is

difficult and active extension is easily achieved. Gentle static

individual joint extension splinting is helpful in the presence of

impending flexion contractures. Discomfort may be minimized by using a

static wrist support in neutral position. Delay full dynamic extension

splints that fully stress the lysed tendon until 2 to 6 weeks,

depending on tendon status.

lubrication and scar-remodeling techniques. Scar massage and elastomer

molds help soften and flatten dense elevated or adherent scars.

Continue to emphasize exercise, adding joint blocking and full flexion

and extension of the digits with the wrist in a dorsiflexed position.

additional protection may be required. Fit the patient with a dorsal

protective splint, maintaining the wrist and MP joints in flexion to

protect the lysed tendon. Elastic traction, as described, with primary

tendon repairs may be applied until 4 weeks postoperatively. Limit

active exercise to passively flexing the involved digits; then ask the

patient to actively maintain the position while the passive force is

removed. This may be followed with full active extension within the

protection of the splint, and will achieve the goal of maximum flexor

excursion while reducing the potential risk of rupture.

earlier, remain investigational. Their use following tenolysis,

particularly when capsulectomy was also required, appears beneficial,

but active motion with proximal blocking is also necessary, as with the

standard technique.

soft-tissue pliability during new sheath formation around the implant.

In stage 2, the goal is to restore passive mobility and achieve a

gliding graft within the pseudosheath for optimum active mobility.

postoperatively, as a result of implant surface contaminants, buckling

of the implant, or overzealous therapy. This can usually be avoided

with careful handling of the implant, appropriate pulley reconstruction

at surgery, and careful postoperative management. Synovitis is

characterized by discomfort in the operated digit and swelling with no

signs of systemic illness. It is treated with immediate rest and

immobilization. Concurrent procedures such as capsulectomy require

specific management, but in harmony with the overall plan. Immediate

postoperative dynamic splinting may be indicated if capsulectomies have

been performed.

the proximal attachment and rupture of the graft. If it is apparent

that adhesions are limiting motion during the first 5 weeks after the

second stage (as indicated by the absence of gradual improvement of