Examination of the Patient With Visual Symptoms

Authors: Lewis, Steven L.

Title: Field Guide to the Neurologic Examination, 1st Edition

Copyright ©2004 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Section 3

– Neurologic Examination in Common Clinical Scenarios > Chapter 49 –

Examination of the Patient With Visual Symptoms

– Neurologic Examination in Common Clinical Scenarios > Chapter 49 –

Examination of the Patient With Visual Symptoms

Chapter 49

Examination of the Patient With Visual Symptoms

GOAL

The goal of the history and examination of the patient

with visual symptoms is to determine whether the symptoms are due to

vision loss or diplopia and to determine the most likely cause of that

dysfunction.

with visual symptoms is to determine whether the symptoms are due to

vision loss or diplopia and to determine the most likely cause of that

dysfunction.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF VISUAL DYSFUNCTION

Visual dysfunction, whether transient or persistent, can occur as a result of one of two main mechanisms: vision loss or diplopia.

-

Vision loss can occur due to dysfunction

anywhere along the sensory visual pathway that begins in the eyes and

ends in the occipital cortex (see Chapter 13, Visual Field Examination, and Fig. 13-1). -

Diplopia is the illusion of seeing two

objects when there is really only one and occurs when there is

dysfunction of normal conjugate eye movements so that the eyes no

longer move appropriately in synchrony. The presence of diplopia

implies dysfunction of the motor pathways that move the eyes, anywhere

from the brainstem to the extraocular muscles. Because the illusion of

diplopia requires two eyes, patients who are blind in one eye cannot

have diplopia.

TAKING THE HISTORY OF A PATIENT WITH VISUAL DYSFUNCTION

Listed below are important features of the history that

can be helpful in the evaluation of patients who present with symptoms

due to vision loss or diplopia.

can be helpful in the evaluation of patients who present with symptoms

due to vision loss or diplopia.

Vision Loss

Monocular Vision Loss

-

Monocular vision loss

may be transient or persistent. When patients present with transient

visual symptoms that they attribute to one eye, for you to be more

certain that your patient’s symptom was truly monocular and not a

hemianopic disturbance, the patient would have had to have covered the

bad eye during the event to confirm that the vision was intact in the

good eye. Some patients do initiate this test on their own during an

episode of vision loss, but you may need to specifically inquire if the

patient did this. -

Patients with monocular visual problems

do not usually present with significant functional deficits from their

vision loss, as long as the remaining eye has intact visual fields. In

other words, unlike patients with hemianopsias, patients with purely

monocular vision loss are less likely to bump into objects because of

their visual dysfunction. -

Amaurosis fugax (meaning fleeting blindness)

is an important kind of transient monocular vision loss that may be

seen in patients with retinal ischemia, such as can be associated with

carotid stenosis or temporal arteritis. Patients describe a brief

(seconds or minutes) loss of vision in

P.167

one eye as “like a shade coming down.” As the symptoms resolve, the patient may describe the shade coming back up. -

Patients with optic neuritis usually

present with monocular vision loss that progresses over a period of

days and lasts for weeks, and it is often associated with pain on eye

movement.

Visual Field Loss

-

Patients with visual field loss

often do not recognize the concept of a visual field or a visual field

deficit. They may misinterpret their homonymous visual field deficits

as monocular (i.e., a patient may interpret a left homonymous

hemianopsia as a visual problem involving the left eye alone). -

Patients with hemianopic visual field

cuts sometimes present with symptoms of the consequences of their

deficits, rather than with a primary visual complaint. They may tell

you they consistently bump into objects on one side, or they may have

been involved in a motor vehicle collision because of their visual

deficit. -

Patients with hemianopsias may present

with a vague visual complaint that they have difficulty describing.

Those with left homonymous hemianopsias may complain of difficulty

reading, not recognizing that their difficulty is due to consistently

missing the first (left) parts of sentences. Patients with bitemporal

field loss may complain of difficulty with their peripheral vision. -

A common form of transient hemianopic

field deficit is the visual disturbance of a migraine aura. Migrainous

visual disturbances typically present as a scintillating (shining)

zigzag or herringbone-like pattern, sometimes in the form of a C,

occurring in the left or right visual field and gradually growing over

approximately a 15-minute period before resolving. This migrainous

visual disturbance may or may not be followed by a headache. -

Patients with complete bilateral vision

loss due to bilateral occipital lobe infarcts can actually be unaware

that they are blind and deny the existence of their blindness. This is

known as Anton’s syndrome.

Diplopia

-

Patients with diplopia usually are aware

of seeing two objects, which (depending on the cause) can be side by

side, vertical, or diagonal. Horizontal diplopia would be particularly

likely from sixth nerve lesions or disorders affecting the lateral or

medial rectus muscles alone. Vertical or diagonal diplopia would be

expected with lesions causing the eyes to diverge vertically or

diagonally but is otherwise not specific in terms of localization. -

Diplopia should completely resolve when

the patient covers either eye. Some patients instinctively perform this

test themselves, but you may need to specifically ask if they did,

especially if the diplopia was transient and is no longer present

during your examination. -

Some patients who have diplopia complain

only of a vague blurriness of vision, unaware that their difficulty is

actually due to two partially superimposed images. In this case, the

historical clue that the visual symptom is actually diplopia rests on

the finding that the symptoms resolve with covering either eye. -

Diplopia due to myasthenia gravis usually

waxes and wanes like any other weakness associated with this

neuromuscular junction disease. The diplopia may be worse at the end of

the day and may be associated with eyelid drooping.

P.168

EXAMINING THE PATIENT WITH VISUAL DYSFUNCTION

The following are important features of the examination of patients who present with symptoms due to vision loss or diplopia:

Vision Loss

Monocular Vision Loss

-

In patients with monocular vision loss

due to optic nerve dysfunction (such as optic neuritis), the visual

field in the affected eye may be a central scotoma. This is easily

detected by asking the patient to cover the good eye and look directly

at your face with the bad eye. The patient with a central scotoma

describes inability to see the central part of your face but is able to

see the periphery. -

On pupillary examination, patients with

monocular vision loss due to optic nerve dysfunction also usually have

an afferent pupillary defect (see Chapter 10, Examination of the Pupils). -

Acute monocular vision loss due to optic nerve demyelination or inflammation may be associated with optic disc swelling (see Fig. 11-2)

if the process involves the optic nerve head itself (papillitis);

however, the optic disc will appear normal if the disease process is

behind the eye (retrobulbar optic neuritis). Long-standing monocular

vision loss from severe optic nerve dysfunction is often associated

with significant pallor of the optic disc due to optic nerve atrophy

(see Fig. 11-4). -

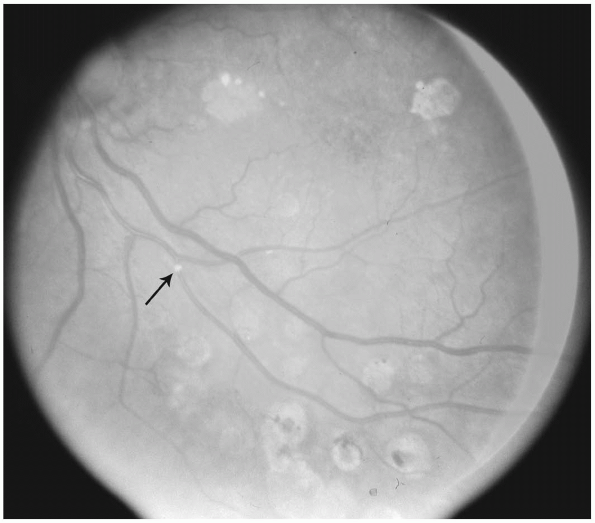

Patients with transient monocular vision

loss (amaurosis fugax) from carotid stenosis may or may not have other

evidence for carotid disease on examination, such as a bruit. They may

also rarely have refractile (bright) embolic material at the branch

points of one or several retinal arterioles visible on funduscopy,

called Hollenhorst plaques (Fig. 49-1).

Hemianopsia

-

In patients with symptoms suggestive of a visual field cut, confrontational visual field testing (see Chapter 13,

Visual Field Examination) will usually easily detect a deficit (i.e., a

left or right homonymous hemianopsia, quadrantanopsia, or bitemporal

hemianopsia). -

Pupillary responses should be normal in

patients with hemianopic visual field deficits (as well as in patients

with complete vision loss due to bilateral occipital pathology) because

the lesion is posterior to the optic chiasm.

Diplopia

-

While examining a patient with diplopia,

ask the patient to describe the characteristics of the two images to

you. This may require the patient to look at an object in the room and

tell you whether the two images are side by side (horizontal diplopia),

up and down (vertical diplopia), or diagonal. -

Confirm that the diplopia resolves when

the patient covers either eye; this simply further confirms that the

patient’s symptoms fit with diplopia. -

Look at the resting position of the eyes

as the patient looks straight ahead. The affected eye of patients with

third nerve palsies, for example, characteristically deviates laterally

and downward (see Fig. 10-1).P.169 Figure 49-1 Retinal artery embolus (arrow) in a patient with carotid atherosclerosis.

Figure 49-1 Retinal artery embolus (arrow) in a patient with carotid atherosclerosis. -

Look closely at the extraocular movements. Particularly, look for evidence of a third or sixth cranial nerve palsy (see Chapter 14, Examination of Eye Movements), and look for pupillary findings suggestive of a third nerve palsy (see Chapter 10, Examination of the Pupils). Also look for evidence of an internuclear ophthalmoplegia (see Fig. 14-2).

-

Patients with fourth nerve palsies are

recognized more by the characteristic head tilt they adopt (as a

compensation for the diplopia that would occur if they didn’t hold

their head in that position) than the subtle eye movement changes that

would be expected from weakness of the superior oblique muscle.

Patients with fourth nerve palsies usually tilt their head away from

the side of the fourth nerve lesion (i.e., a left fourth nerve palsy

would likely cause a head tilt to the right). -

The finding of proptosis in a patient

with diplopia suggests that the lesion is within the orbit or involves

the eye muscle itself. -

If myasthenia gravis is suspected as a cause of diplopia, look for fatigability of the eye muscles as follows:

-

Ask the patient to follow your finger with his or her eyes upward as you raise your finger up to test upward gaze.

-

Continue holding your finger above the

patient’s head as you observe the patient perform a prolonged upgaze.

Watch for a minute or two (your arm may get tired before the patient

does) while you observe the patient’s eyes. -

The finding of fatigability of upgaze or

worsening ptosis with this procedure can be a helpful clue to the

diagnosis of myasthenia gravis even if eye muscle weakness or ptosis is

not seen on routine testing.

-