Continuous Terminal Nerve Blocks

Editors: Chelly, Jacques E.

Title: Peripheral Nerve Blocks: A Color Atlas, 3rd Edition

Copyright ©2009 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Section

VI – Continuous Nerve Blocks in Infants and Children > 58 –

Continuous Terminal Nerve Blocks

VI – Continuous Nerve Blocks in Infants and Children > 58 –

Continuous Terminal Nerve Blocks

58

Continuous Terminal Nerve Blocks

Maria Matuszczak

A. Continuous Axillary Blocks

The axillary artery in the axilla crease is identified. The insertion

point is directly next to the artery at the lateral border of the

axillary crease.

In an appropriately anesthetized/sedated child the needle is inserted

directly next to the artery, pointing almost parallel to the artery in

a proximal direction with a 30° to 45° angle to the skin. As

appropriate muscle twitches in the hand are still present at a current

of 0.5 mA, the local anesthetic solution is slowly injected after

negative aspiration for blood. Maintaining the introducer needle in the

same position, the catheter is threaded 2 cm beyond the needle tip (Fig. 58-2). The introducer needle is removed and the catheter is secured in place with benzoin and a transparent adhesive dressing.

P.382

|

|

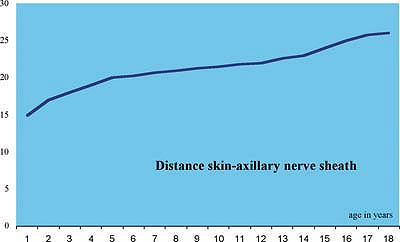

Figure 58-1. Skin–nerve distance, axillary approach.

|

-

At this level, there are no vital structures and it is a perfect approach for beginners in pediatric peripheral nerve blocks.

-

By introducing the needle more distally

from the axilla crease, the catheter can be placed close to a specific

nerve that needs to be anesthetized. -

Because of shoulder mobility the axillary catheter is easily dislocated.

-

To prevent easy dislocation, the catheter

can be tunneled by inserting a longer needle subcutaneously at the

midhumeral level toward the axillary crease. Only when the needle is

close to the axillary crease, look for nerve stimulation. -

In obese children, ultrasound guidance facilitates this approach.

-

This approach can be used to rescue an

incomplete continuous infraclavicular block. Ulnar distribution is

sometimes missed by the infraclavicular approach. -

Ultrasound can be used to localize the

axillary nerves, to position the needle, and to verify that the local

anesthetic is injected via the catheter around the nerves. -

A stimulating catheter can be used in older children.

|

|

Figure 58-2. Axillary catheter placement.

|

P.383

|

Table 58-1. Maximal Initial Volume Bolus of Ropivacaine 0.2%

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Suggested Readings

Dadure C, Capdevila X. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks in children. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2005;19(2):309–321.

Dadure

C, Pirat Ph, Raux O, et al. Perioperative continuous peripheral nerve

blocks with disposable infusion pumps in children: A prospective

descriptive study. Anesth Analg 2003;97:687–690.

C, Pirat Ph, Raux O, et al. Perioperative continuous peripheral nerve

blocks with disposable infusion pumps in children: A prospective

descriptive study. Anesth Analg 2003;97:687–690.

Dalens B. Regional anesthesia in infants, children, and adolescents. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1995.

De la Linde CM, Polo A, Lopez-Andrade A. Continuous axillary plexus block in pediatrics. Rev Esp Anesthesiol Reanim 1997;44:87–88.

Diwan R, Vas L, Shah T. Continuous axillary block for upper limb surgery in a patient with epidermolysis bullosa simplex. Paediatr Anaesth 2001;11:603–606.

Ivani G, Mossetti V. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks. Paediatr Anaesth 2005;15:87–90.

Marhofer P, Frickey N. Ultrasonographic guidance in pediatric regional anesthesia. Part 1: theoretical background. Paediatr Anaesth 2006;16(10):1008–1018.

Mezzatesta

JP, Scott DA, Schweitzer SA, et al. Continuous axillary brachial plexus

block for postoperative pain relief: intermittent bolus versus

continuous infusion. Reg Anesth 1997;22:357–362.

JP, Scott DA, Schweitzer SA, et al. Continuous axillary brachial plexus

block for postoperative pain relief: intermittent bolus versus

continuous infusion. Reg Anesth 1997;22:357–362.

Roberts S. Ultrasonographic guidance in pediatric regional anesthesia. Part 2: techniques. Paediatr Anaesth 2006;16:1125–1132.