Continuous Interpleural Block

Lateral decubitus with the arm dangling anteriorly and cephalad so as

to rotate the scapula forward and expose the posterolateral chest wall.

Postoperative analgesia following mastectomy, nephrectomy, and

cholecystectomy. Analgesia for rib fractures, pancreatitis, neuralgia,

and invasive tumor of the chest wall, flank, and retroperitoneum.

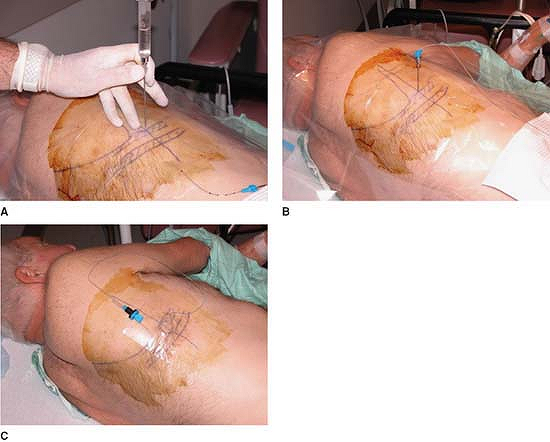

The site of needle insertion is at the seventh or eighth intercostal

space at the level of the tip of the scapula and the cephalad border of

the rib in a vertical direction perpendicular to the chest wall. Once

inserted to a depth of 1 cm into the intercostal muscles, a syringe

(with its plunger removed) is attached to the needle. The open syringe

barrel is filled with saline. The needle is then slowly advanced while

observing for both a “clicking” sensation and a downward movement (the

“falling column”) of the saline as it is drawn into the chest by the

negative pleural pressure. The syringe is removed (Fig. 30-1B)

and the epidural catheter threaded 6 to 10 cm into the interpleural

space. The Tuohy needle is removed, and the catheter is secured with 12

mm × 100 mm Steri-Strip (3M, St. Paul, MN) and covered with a

transparent dressing (Fig. 30-1C).

-

An alternative site is 8 to 10 cm lateral from the posterior midline.

-

Interpleural blockade routinely causes

pneumothorax due to the entrance of air through the needle. This is

typically of small degree (<10%) and asymptomatic. The risk of lung

injury is reduced by the use of proper technique and by avoiding

percutaneous

P.257

placement

in patients with pulmonary bullae or those likely to have pleural

adhesions. Proper technique includes (a) the use of a visual end point

such as the “falling column” technique as opposed to a

“loss-of-resistance” technique, and (b) placement during spontaneous

ventilation as opposed to controlled ventilation or apnea. Figure 30-1. A: Anatomic landmarks. B: The syringe is removed and the epidural catheter threaded 6 to 10 cm into the interpleural space. C: The Tuohy needle is removed, and the catheter is secured and covered with a transparent dressing.

Figure 30-1. A: Anatomic landmarks. B: The syringe is removed and the epidural catheter threaded 6 to 10 cm into the interpleural space. C: The Tuohy needle is removed, and the catheter is secured and covered with a transparent dressing. -

As a result of drug sequestration, uneven

distribution, and drug loss through chest tubes, interpleural block has

not proven particularly useful after thoracotomy. However, satisfactory

blockade can, at times, be achieved in the presence of a chest tube

(e.g., rib fractures) by clamping the chest tube for 30 minutes

following intermittent bolus of local anesthetic. -

Placement at too low an intercostal space can lead to intraperitoneal placement of the needle and catheter.

-

The catheter should thread freely without

resistance, which may indicate improper placement, lung penetration, or

the presence of pleural adhesions. -

Epinephrine should be added to any bolus to reduce peak systemic levels of local anesthetic.

-

Patient positioning will determine where

the local anesthetic pools are, where it traverses the parietal pleura,

and which nerves are affected. Lateral position (blocked side up) will

promote blockade of the sympathetic chain while a supine or lateral

position (blocked side down) will promote blockade of the intercostal

nerves. A

P.258

Trendelenburg

position will promote upper thoracic and cervical sympathetic blockade

(producing Horner syndrome) and even, at times, blockade of inferior

roots of the ipsilateral brachial plexus. -

Interpleural block is most useful when

combined with multimodal analgesic therapies which may include

nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or a COX-2 inhibitor

(celecoxib), NMDA blockade, alpha-2 agonists, A-2 delta calcium channel

blockade (pregabalin), and opiates. -

To minimize risk of systemic toxicity

from the rapid reabsorption of local anesthetic solution in the

interpleural space, lidocaine may be the preferred local anesthetic for

infusion. While this author has typically used a 1% solution, a lower

concentration may prove adequate. -

Interpleural block will not usually

provide the degree of neural blockade seen with thoracic paravertebral

block (TPVB), but its simplicity is especially useful in certain

patients, for example, the ventilated ICU patient with multiple rib

fractures who is receiving low molecular weight heparin anticoagulation.

CE, Kirz LI, VadeBoncouer TR, et al. Continuous infusion of

interpleural bupivacaine maintains effective analgesia after

cholecystectomy. Anesth Analg 1991;72:516–521.

DP, Lema MJ, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Interpleural analgesia for the

treatment of severe cancer pain in terminally ill patients. J Pain Symptom Management 1993;8:505–510.

Kleef JW, Logeman EA, Burm AG, et al. Continuous interpleural infusion

of bupivacaine for postoperative analgesia after surgery with flank

incisions: a double-blind comparison of 0.25% and 0.5% solutions. Anesth Analg 1992;75:268–274.