CHAPTER 25 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 25 – Arthroscopic Management of Shoulder Stiffness

The diagnosis of shoulder stiffness, also termed frozen shoulder or adhesive capsulitis, is one of exclusion. It is a clinical syndrome characterized by painful restricted passive and active range of motion. It is associated with night pain and pain with activities. [1] [5] [6] [7] [11] This clinical entity has been difficult to classify and follows an unpredictable clinical course. [1] [2] [6] [15] The pathophysiologic mechanism of the disease can include idiopathic, posttraumatic, and postsurgical etiologic factors and diabetes; it can even occur as a consequence of prolonged impingement syndrome. [7] [10] [11] [16] [17] [18] It appears that susceptible shoulders respond to an insult in a common pathway of expression; this is glenohumeral synovitis. If this process continues unabated, the capsule will become thickened and disorganized in its collagen structure and actually become contracted. [3] [13] The time course of the process and recovery is unpredictable. The true etiology, diagnostic criteria, pathophysiology, treatment methods, and natural history of this condition are under debate and investigation. [1] [2] [7] [10] [11] [12] [14] [15] [19] There are patients who do not respond to time, proper therapy, injections, or anti-inflammatory medications and are profoundly affected by the shoulder stiffness. These patients can be offered an arthroscopic capsular release.

The majority of patients with adhesive capsulitis of idiopathic etiology are women between the ages of 35 and 60 years. A history should be taken for other contributing factors, especially endocrine abnormalities such as diabetes and hypothyroidism. A history of trauma or surgery is important to note. A neurologic history is important to note for possible involvement of cervical disease. The type of prior surgical procedure on or around the shoulder is important, and a previous operative note can be helpful.

Adhesive capsulitis, or frozen shoulder, is a limitation of motion without an obvious clinical reason for the loss of motion, such as arthritis or previous fracture of the shoulder. Thus, a comprehensive examination of the shoulder and cervical spine needs to be performed. The examiner should evaluate passive motion and active motion in forward elevation in the plane of the scapula, external rotation at the side, and internal rotation. In a stiff shoulder, internal rotation behind the back can be painful. It is helpful to evaluate internal rotation with the arm abducted in the scapular plane approximately 40 degrees and then let the forearm drop toward the floor. Thus, rotation can be evaluated and measured, and the early movement of the scapula is easily seen in those patients with posterior capsular involvement. The affected side should always be compared with the nonaffected side, and the shoulder girdle should be inspected for atrophy. Evaluation for acromioclavicular joint pain, impingement-type pain, and cervical radicular symptoms must be done. In this systematic fashion, the examiner can determine the motion planes that are involved and evaluate any contributing factors to the loss of motion and pain patterns.

It can be helpful to perform differential injections around the shoulder to determine pathologic locations and contributions. A subacromial injection of anesthetic can remove subacromial pain generators and allow the examiner to evaluate the shoulder with that area temporarily “eliminated.” An injection in the glenohumeral joint itself can eliminate glenohumeral pain, thus allowing the examiner to evaluate shoulder motion again with pain eliminated. If the motion is remarkably improved, it may not be a true shoulder stiffness problem. Most times, however, the injections help the pain aspect, but the range of motion is not improved, confirming a diagnosis of stiffness.

Plain radiographs evaluate conditions such as arthritis of the glenohumeral joint, calcific tendinitis, and subacromial impingement. A true anteroposterior view of the glenohumeral joint, an axillary view, and an outlet view should be performed.

Magnetic resonance imaging can evaluate for rotator cuff disease; but in a true adhesive capsulitis picture, magnetic resonance imaging will exclude other pathologic processes. Bone scan, computed tomographic scan, and electromyography are rarely necessary for the evaluation of frozen shoulder. Arthrography with limited joint volume was at one time thought to be a “gold standard” type of test,[6] but it is not necessary for the diagnosis of shoulder stiffness if a proper history and physical examination are performed.

Conservative treatment should always be attempted. As mentioned previously, injections can relieve pain and facilitate therapy. The pathophysiologic process is that of glenohumeral inflammation. Corticosteroid injections into the glenohumeral joint can decrease the inflammatory response, relieve pain, and allow better motion. An oral steroid medication can also be administered. Gentle range of motion and stretching are instituted. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication can be prescribed after or in conjunction with steroids. If the pain is relieved, most patients can accept the limitations of motion. [2] [15] This allows more time to restore motion and function. A patient not responding to or becoming worse with a therapy program designed specifically for shoulder stiffness can be a candidate for arthroscopic capsular release.

Indications and Contraindications

Indications for Surgical Intervention

There are those patients who do not respond to conservative management. A recalcitrant frozen shoulder is one that has had symptoms for more than 4 months and has not responded to a surgeon-designed therapy program directed toward the diagnosis of shoulder stiffness. This program should be given at least 6 weeks to show progress. If patients still have sleep disturbance, pain, and limitation of motion that affects their occupation, recreation, and sleep, it is time to consider an arthroscopic capsular release. [7] [8] [9] The etiology of the stiffness was not found to have a significant effect on the outcome of arthroscopic capsular release; thus, it is equally effective across causes.[7]

Contraindications for an Arthroscopic Capsular Release

If the patient has motion loss and a shoulder prosthesis in place, an open approach may be preferred. If there is motion loss and a history of an open instability repair that used a subscapularis shortening procedure, an open approach may be preferred.

By definition, there is restricted range of motion of the shoulder; thus, there is small joint volume, and small movements can help intraarticular exposure. For this reason, the preference is for the beach chair position with the arm free. The lateral position with the arm in traction will restrict the ability to rotate the shoulder during the procedure, and traction will not open up the contracted joint. A combined anesthetic technique, such as a light general anesthetic with a scalene regional block for intraoperative and postoperative pain relief, is preferred. If the patient is going to be admitted for therapy, an indwelling scalene catheter can be used for prolonged pain control. The surgeon should choose the best option on the basis of the patient and the experience of the anesthesia and surgical team.

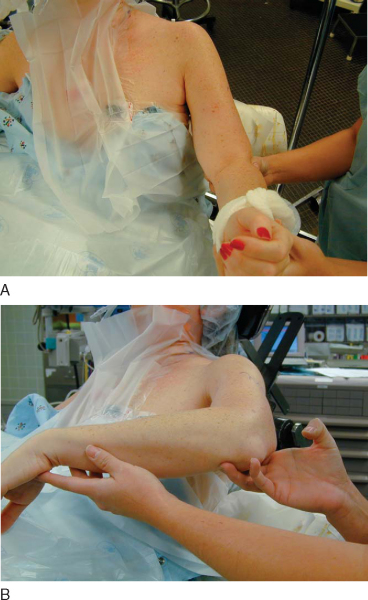

The patient is placed in the beach chair position with a small towel roll under the medial border of the scapula. The landmarks of the scapular spine, acromion, and coracoid are marked after standard preparation and draping. An assessment of motion is made under anesthesia (

Fig. 25-1

). No manipulation is performed at this time because it would cause bleeding within the glenohumeral joint and make for a more difficult procedure.

|

|

|

|

Figure 25-1 |

The surgeon’s knowledge of the chosen pump is underrated but important. Proper fluid management during the case facilitates a clear field and prevents unnecessary swelling. It is helpful to use a 1 : 300,000 dilution of epinephrine in the fluid, which helps decrease bleeding. My preference for the release instrument is the ArthroWand bipolar cautery device (ArthroCare, Sunnyvale, Calif). The 3.5-mm, 90-degree (non–turbo vac) model allows a 3.5-mm swath of tissue to be cut without bleeding. It is a stiff instrument that allows the surgeon to cut and to manipulate the tissue by both pushing away and pulling back toward the portal. The right angle at the tip allows the surgeon to cut into tissue and around corners. Other devices have been used to perform the capsular release, including monopolar devices, basket cutters, and shavers. [4] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [14] [17] A combination of release tools can be used, depending on the surgeon’s preference.

Specific Steps (

Box 25-1

)

After motion assessment, the glenohumeral joint is insufflated with saline with an 18-gauge spinal needle from the posterior portal. The posterior portal is placed approximately 2 cm medial and inferior to the posterolateral corner of the acromion. A stab wound is made at this spot, and the blunt obturator for the arthroscopic sheath is introduced into the joint. The joint is contracted and the capsule is thickened. The tip of the scope sheath is aimed at the superior aspect of the glenoid toward the long head of biceps origin. This will allow the arthroscopic sheath to enter a more open area of the joint and avoid articular cartilage damage.

| Surgical Steps | |||||||||||||||

|

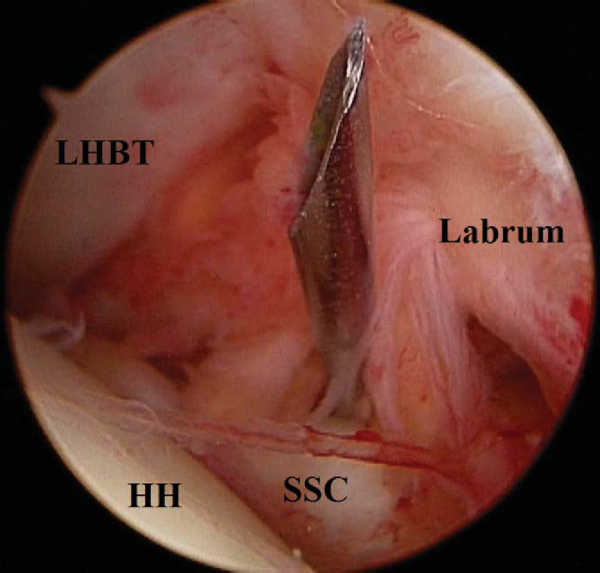

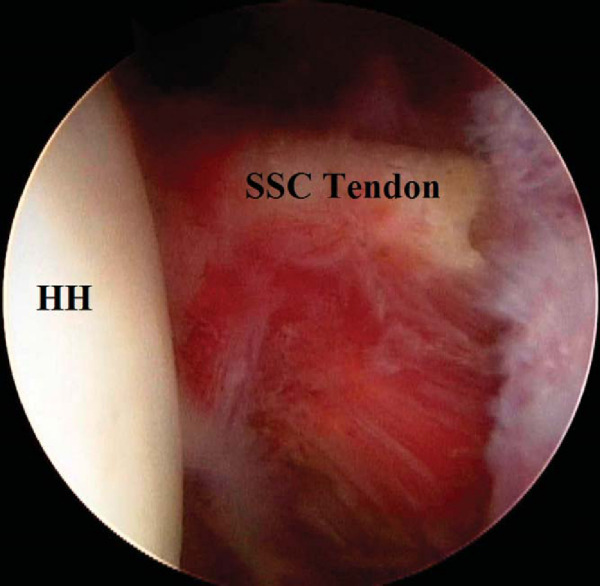

The arthroscope is connected, and visualization of the arthroscopic triangle is achieved. The arthroscopic triangle formed by the long head of the biceps tendon, the glenoid, and the top of the subscapularis tendon is typically contracted and involved with a red, gelatinous synovitis (

Fig. 25-2

). The spinal needle is inserted anteriorly just lateral to the tip of the coracoid and into the arthroscopic triangle. A stab wound is made anteriorly, and a smooth cannula is placed into the joint through the arthroscopic triangle. Fluid flow will allow visualization. The shaver is brought in to débride the accessible synovitis. This gelatinous synovium is easily débrided without significant bleeding. At this point, the smooth cannula is removed and the ArthroWand is brought in anteriorly down the track created by the cannula. There is no need to attempt to bring the device through the cannula because it will restrict mobility.

|

|

|

|

Figure 25-2 |

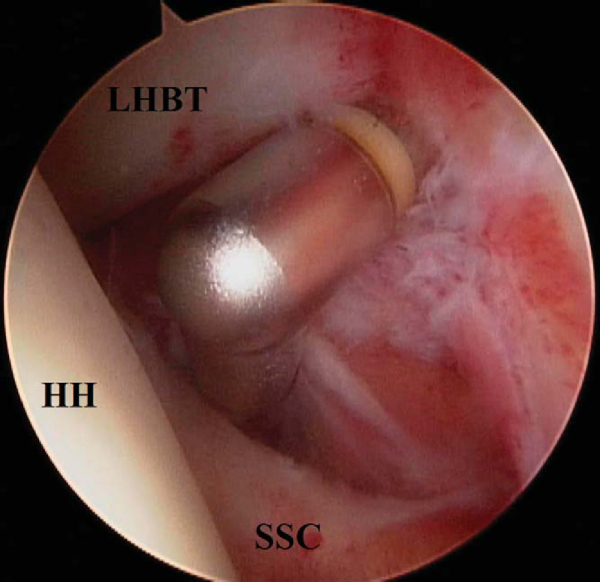

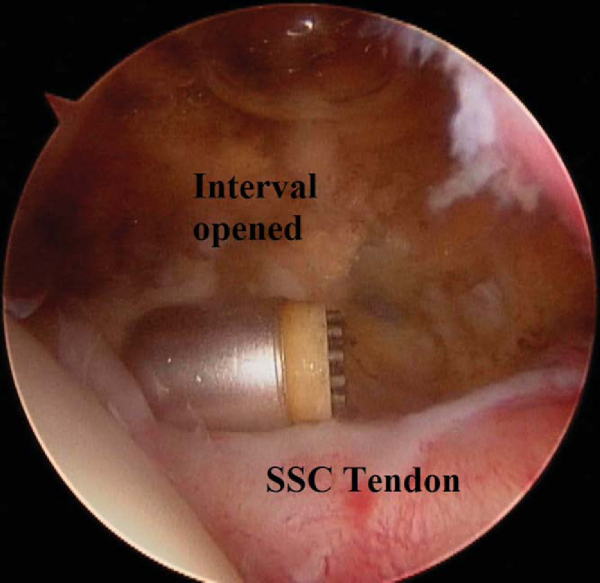

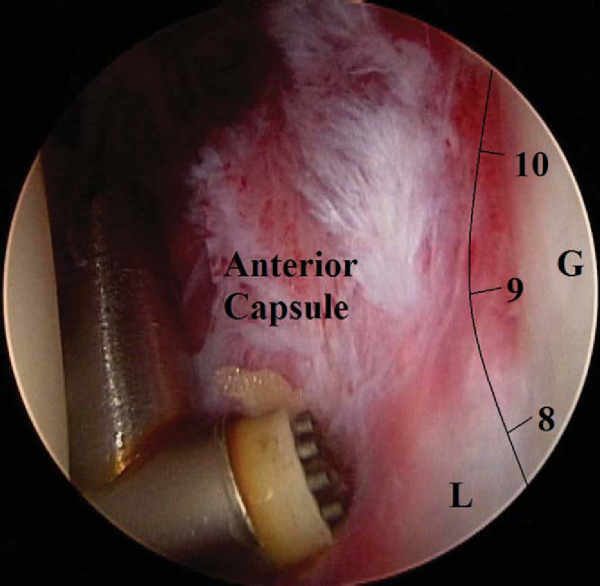

2. Rotator Interval and Anterosuperior Release

The arthroscopic capsular release must begin superiorly and proceed inferiorly, thus “unzipping” the shoulder. The cautery device begins the release just below the biceps tendon in the rotator interval (

Fig. 25-3

). The “base” of the triangle is released and then carried across the top of the subscapularis tendon (

Fig. 25-4

). This provides mobility to proceed inferiorly. An extralabral capsular release is performed (

Fig. 25-5

). The thickened capsule is cut or released by the cautery device. Mobility and visualization in the inferior aspect of the joint improve as the release continues from superior to inferior down the anterior capsule (

Fig. 25-6

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 25-3 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 25-4 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 25-5 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 25-6 |

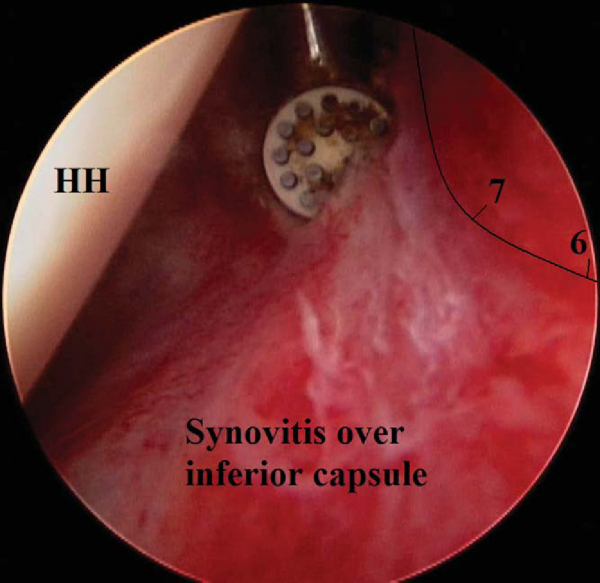

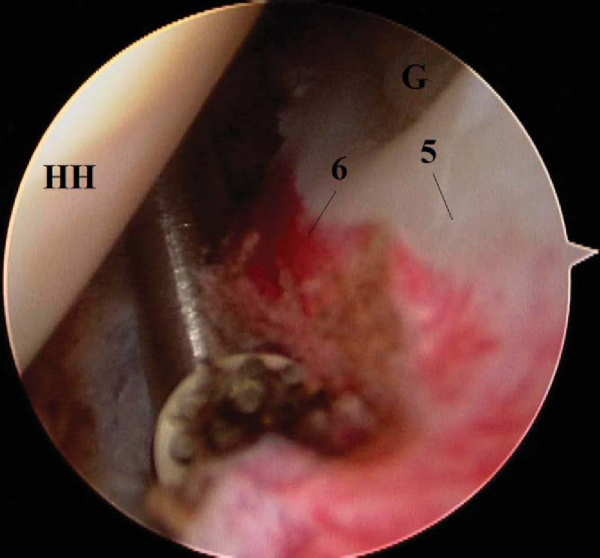

As the ArthroWand cautery device gets down inferiorly (from the 5- to 7-o’clock position), the device is turned facing superiorly to cut the capsule (

Fig. 25-7

) while preventing injury to the axillary nerve. The device is also kept along the rim of the glenoid; drifting away from the glenoid rim can endanger the axillary nerve.

|

|

|

|

Figure 25-7 |

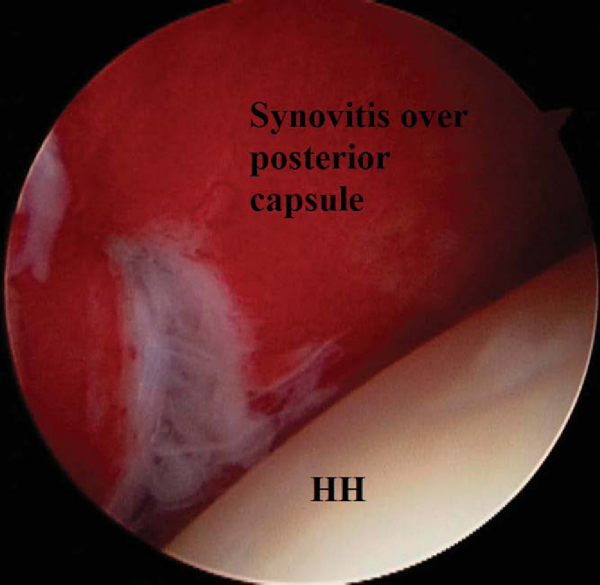

Once the 5- or 6-o’clock position is reached, the arthroscope is switched to the anterior portal and the cautery device to the posterior portal. The capsular release is now repeated from superior to inferior and extralabral, but along the posterior capsule (

Fig. 25-8

). The region above the biceps origin, the posterosuperior recess, should be addressed and released if it is found to be contracted. This capsular area can restrict the excursion of the supraspinatus tendon unit.

|

|

|

|

Figure 25-8 |

After the capsule has been circumferentially released, the subacromial space is evaluated. In patients with previous surgery or impingement, the subacromial space can be involved, in which case [7] [8] [9] [11] [18] any adhesions should be débrided and an acromioplasty performed. If the patient has developed acromioclavicular joint pain during the stiffness process, it should be addressed at this time.

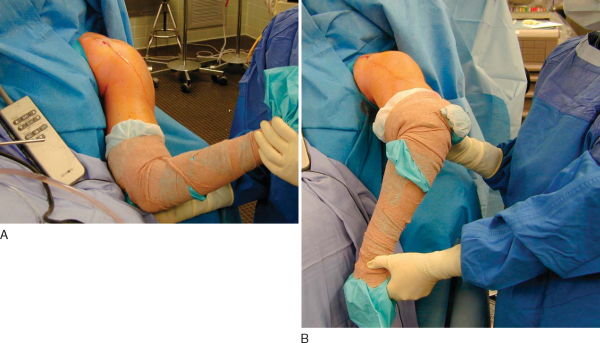

Finally, the shoulder is put through a gentle manipulation. A sequence of forward elevation in the plane of the scapula, external rotation at the side, abduction, and internal rotation is performed holding the proximal humerus, thus lowering the moment arm and decreasing the risk of a humerus fracture. A few soft releases may be felt, representing the last few contractures being lysed. This is not a true manipulation. The capsular release provides for a controlled, bloodless, atraumatic manipulation with this range of motion at the end of the procedure (

Fig. 25-9

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 25-9 |

The majority of patients are admitted for a 24-hour stay to allow physical therapy while the scalene regional block is in effect. This provides an opportunity for pain-free motion exercises. It also shows the patients that motion has been restored and can be achieved without pain. This is a big psychological step for many patients who have battled pain, poor motion, and dysfunction for a prolonged time. If the surgeon elects in-hospital treatment in this fashion, it is recommended to try to schedule the case early in the morning, so that the therapist can see the patient while the block is still in effect. Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications are routinely prescribed to control pain and inflammation. I have used a derotation sling and wedge (Apex sling; EBI Inc., Parsippany, NJ) to place the shoulder in a neutral position and avoid the internally rotated position typically seen with a traditional sling.

Outpatient therapy emphasizing motion for forward elevation, external rotation, and internal rotation is performed 3 days a week for 3 weeks, then 2 days a week for 3 weeks more. Patients are to perform daily range-of-motion exercises at home for 20 to 30 minutes, three times a day. Isometric strength and resistive strength exercises are not prescribed until motion is pain free, flexible, and consistent, approximately after 6 to 8 weeks. The time to final pain-free range of motion is approximately 6 to 10 weeks. [7] [14] [17] [19] The need for home continuous passive motion therapy is rare, but it should be considered in those patients who may be at higher risk for slow progress, such as diabetic patients with profound motion loss (external rotation at side less than 0 degrees) and those for whom a previous stiffness procedure (manipulation or release procedure) has failed.

The goal is a balanced capsular release. This cannot be accomplished with manipulation alone. One of the pitfalls is to not accomplish the balanced release and to leave one of the areas not addressed. Thus, the surgeon should always assess and address the anterior, inferior, and posterior capsular regions. The interval should always be released and the subacromial space evaluated. Even with good technique, I have found that approximately 20% of patients will develop a transient decrease in motion 3 to 5 weeks after the procedure. The shoulder motion becomes less flexible and can actually become “rubbery” and painful. This is an inflammatory flare-up and has been described by other authors. [7] [19] It should be recognized and the patient reassured and treated with patience, anti-inflammatory medication, and, if it is not contraindicated, either a Medrol dose pack or an intraarticular steroid injection. It will resolve in 3 to 6 weeks.

Other potential complications include injury to the axillary nerve, fracture of the humerus, damage to the joint surface, and recurrent stiffness. There is also the risk of complications from the scalene block. In my experience, the complication rate has been low, and no patient has developed recurrent stiffness after arthroscopic capsular release.

Arthroscopic capsular release has shown the ability to consistently restore range of motion, to improve shoulder function, and to relieve pain for a variety of shoulder stiffness causes (

Table 25-1

and

Fig. 25-10

). [4] [7] [10] [11] [12] [14] [16] [17] [18] [19] It has the potential to shorten the natural history of this still not fully understood clinical entity. Reports on outcomes have shown a time to achieve final pain-free range of motion between 6 and 10 weeks. The time in formal therapy has averaged 2.5 months. The recurrence of stiffness has not been seen. The average improvement in range of motion has been 73 degrees for forward elevation, 44 degrees in external rotation, and 8 spinal segments in internal rotation. The etiology of the stiffness did not have an effect on motion, pain, or satisfaction of the patient. Diabetic frozen shoulder did show a trend toward a longer time to achieve final range of motion but had significant improvement in motion, pain, and function.[7]

| Author | Followup | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Watson et al[19] (2000) | 12 months | 8 of 73 patients had recurrence of pain or stiffness |

| Final motion averaged 90% of contralateral side | ||

| Harryman et al[4] (1997) | Average of 33 months (12-56 months) | 3 of 30 patients had recurrence of shoulder stiffness |

| Final motion averaged 93% of contralateral side | ||

| Warner et al[17] (1996) | Average of 39 months (24-64 months) | 23 patients with average improvement of 48 points in the Constant score |

| Motion returned to within 7 degrees of contralateral side | ||

| Segmuller et al[14] (1995) | 13.5 months | 76% of 24 patients (26 shoulders) returned to near-normal motion |

| 88% of patients very satisfied with procedure |

|

|

|

|

Figure 25-10 |

1.

Grey RG: The natural history of “idiopathic” frozen shoulder.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1978; 60:564.

2.

Griggs SM, Ahn A, Green A: Idiopathic “adhesive capsulitis”: a prospective functional outcome study of nonoperative treatment.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000; 82:1398-1407.

3.

Hannafin JA, DiCarlo EF, Wickiewicz TL: Adhesive capsulitis: capsular fibroplasia of the glenohumeral joint.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1994; 3:S5.

4.

Harryman DT, Matsen FA, Sidles JA: Arthroscopic management of refractory shoulder stiffness.

Arthroscopy 1997; 13:133-147.

5.

Murnaghan JP: Frozen shoulder.

In: Rockwood CA, Matsen FA, ed. The Shoulder, vol 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1993:837-861.

6.

Neviaser RJ, Neviaser TJ: Frozen shoulder: diagnosis and management.

Clin Orthop 1987; 223:59-64.

7.

Nicholson GP: Arthroscopic capsular release for stiff shoulders. Effect of etiology on outcomes.

Arthroscopy 2003; 19:40-49.

8.

Nicholson GP: Adhesive capsulitis. Manipulation or arthroscopic capsular division.

In: Barber FA, Fischer SP, ed. Surgical Techniques for the Shoulder and Elbow,

New York: Thieme; 2003:127-130.

9.

Nicholson GP, Ticker JB: Arthroscopic capsular release.

In: Imhoff AB, Ticker JB, Fu F, ed. Atlas of Shoulder Arthroscopy,

London: Martin Dunitz; 2003:343-351.

10.

Ogilivie-Harris DJ, Myerthall S: The diabetic frozen shoulder: arthroscopic release.

Arthroscopy 1997; 13:1-18.

11.

Ozaki J, Nakagawa Y, Sukurai G, Tomai S: Recalcitrant chronic adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1989; 71:1511-1515.

12.

Pearsall AW, Osbahr DC, Speer KP: An arthroscopic technique for treating patients with frozen shoulder.

Arthroscopy 1999; 15:2-11.

13.

Rodeo SA, Hannafin JA, Tom J, et al: Immunolocalization of cytokines in adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder.

J Orthop Res 1997; 15:427-436.

14.

Segmuller HE, Taylor DE, Hogan CS, et al: Arthroscopic treatment of adhesive capsulitis.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1995; 4:403-408.

15.

Shaffer B, Tibone JE, Kerlan RK: Frozen shoulder: a long term followup.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992; 74:738-746.

16.

Ticker JB, Beim GM, Warner JJP: Recognition and treatment of refractory posterior capsular contracture of the shoulder.

Arthroscopy 2000; 16:27-34.

17.

Warner JJP, Allen A, Marks P, Wong P: Arthroscopic release of chronic refractory capsular contracture of the shoulder.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996; 78:1808-1816.

18.

Warner JJP, Allen A, Marks PH, Wong P: Arthroscopic release of postoperative capsular contracture of the shoulder.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997; 79:1151-1158.

19.

Watson L, Dalziel R, Story I: Frozen shoulder: a 12-month clinical outcome trial.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2000; 9:16-22.