CHAPTER 12 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 12 – Open Repair of Posterior Shoulder Instability

James P. Sieradzki, MD

Recurrent posterior instability of the glenohumeral joint is less common than anterior instability or multidirectional instability. In most series, isolated posterior instability represents less than 5% of shoulder instability. In some cases in which the posterior instability is primary, there may be a component of inferior laxity. In this chapter, we discuss the clinical syndrome that occurs with recurrent episodes of posterior subluxation. This is distinct from the diagnosis and treatment of acute or fixed (missed) dislocation, which is not discussed in this chapter. The etiology of recurrent subluxation can be direct or indirect macrotrauma, repetitive microtrauma, or atraumatic in association with some generalized ligamentous laxity. The pathologic cause of this condition is unclear and has been attributed to excessive humeral retrotorsion, increased glenoid retroversion, thin and patulous posterior capsule, or decreased tension in the posterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament. Increasing evidence suggests that this condition is related to a deficiency of ligamentous-capsular restraints and not to the bony architecture.

Symptoms consist of pain, especially when the shoulder is axially loaded or positioned in forward flexion, adduction, and internal rotation. First-line treatment is physical therapy to develop a stable scapular platform combined with rotator cuff strengthening. Conservative treatment has been most successful in persons with atraumatic causes; surgery is often necessary for traumatic causes. Several open and arthroscopic techniques have been described to treat persistent, symptomatic posterior instability.

A detailed history is mandatory. This includes the injury mechanism, if present; the position of the arm when it is symptomatic; repetitive stresses on the shoulder; the presence of voluntary instability; and previous interventions. In some series, age older than 35 years and previous shoulder surgery, particularly thermal capsulorrhaphy, portended a poorer prognosis with surgical intervention.

Factors Affecting Surgical Indication

| • | Instability series including anteroposterior with internal rotation, axillary lateral, scapular Y, and Stryker notch views |

| • | Computed tomographic scan to evaluate glenoid version | |

| • | Magnetic resonance arthrography to evaluate posterior capsule and labrum |

Indications and Contraindications

This procedure should be considered in a young patient with isolated posterior instability for whom an adequate trial course of physical therapy has failed. The ideal patient has a traumatic cause of the condition and will not have evidence of significant inferior or anterior instability, previous surgery, or degenerative changes. The ability to voluntarily sublux the shoulder by positioning the arm flexed, adducted, and internally rotated and to reduce it with a clunk as the arm is extended does not preclude surgical treatment. However, patients who voluntarily posterior sublux the shoulder with the arm at the side by selective muscle activation should be regarded with caution before proceeding with surgery. Excessive glenoid retroversion is not a contraindication but may affect surgical planning.

Contraindications are few, and most are not absolute. They include multidirectional instability with significant generalized ligamentous laxity and failed previous posterior stabilization. Patients with a psychiatric history, voluntary subluxation, and secondary gain should be avoided.

Issues to be considered at the time of surgery include a confirmatory examination under anesthesia and complete arthroscopic examination to evaluate the shoulder for both related and unrelated pathologic processes. The primary direction of instability should be determined on the basis of the patient’s history and physical examination findings. The examination under anesthesia should be confirmatory, and rarely should the approach to the instability be changed on the basis of the findings on examination at the time of surgery. The arthroscopic examination will determine whether the posterior labrum will need to be repaired as part of the open stabilization. It may also disclose other anterior or superior labral pathologic processes that might be best treated at that time by arthroscopic repair.

This procedure should be performed under a general anesthetic. Regional anesthesia (interscalene block with C4 coverage) may be helpful with postoperative pain management. Positioning for arthroscopy is subject to the surgeon’s preference; both the lateral decubitus and beach chair positions are acceptable. Open stabilization can be performed in the beach chair position, but the exposure can be problematic and requires excellent assistance with retraction for adequate visualization, especially in a muscular shoulder. The “floppy” lateral decubitus position with the arm draped free allows easier retraction and manipulation of arm position during the surgical procedure.

Surgical Landmarks and Incisions

| • | Acromion | |

| • | Axillary crease | |

| • | Glenohumeral joint | |

| • | Posterolateral corner of scapula | |

| • | Posterior portal for shoulder arthroscopy centered over the glenohumeral joint |

| • | Approach: axillary nerve, posterior humeral circumflex vessels inferior to teres minor | |

| • | Capsulotomy: suprascapular nerve, medial to posterior labrum |

Examination Under Anesthesia and Diagnostic Arthroscopy

Before positioning of the patient, it is critical to examine both shoulders under anesthesia to assess asymmetry of range of motion and glenohumeral translation. The examination should confirm grade 2 to 3+ posterior translation with limited anterior and inferior translations.

Diagnostic arthroscopy is helpful to evaluate the glenohumeral joint for other intraarticular pathologic changes, including labral tears, rotator cuff injuries, chondral injuries, biceps tendon or anchor tears, and loose bodies.

Specific Steps (

Box 12-1

)

Diagnostic arthroscopy evaluates the status of the posterior labrum to determine the need for incorporation of an open labral repair versus capsulorrhaphy only. Other labral pathologic processes (anterior or superior) that are found may be repaired arthroscopically at that time. The rotator cuff, biceps tendon, and articular cartilage may also be evaluated and treated as appropriate.

| Surgical Steps | ||||||||||||||||||

|

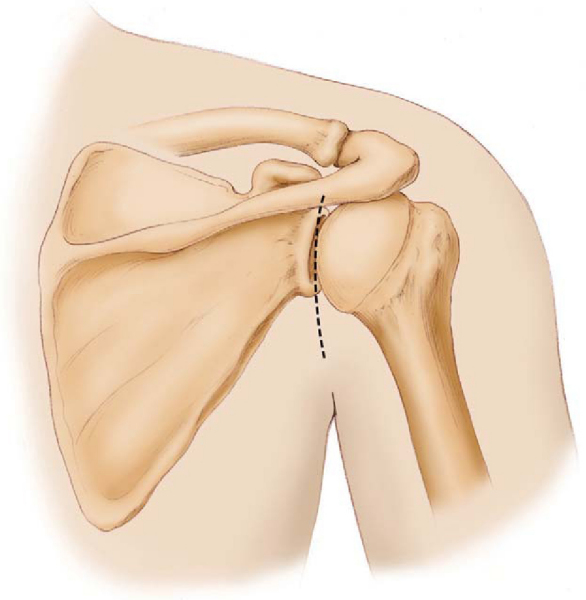

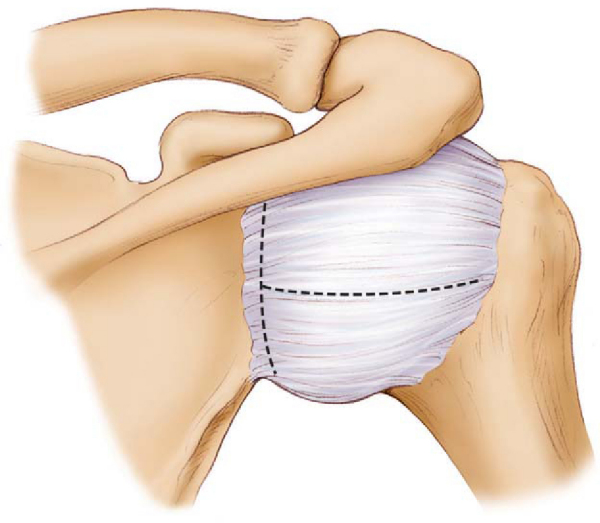

A vertically oriented skin incision is planned, centered over the glenohumeral joint (

Fig. 12-1

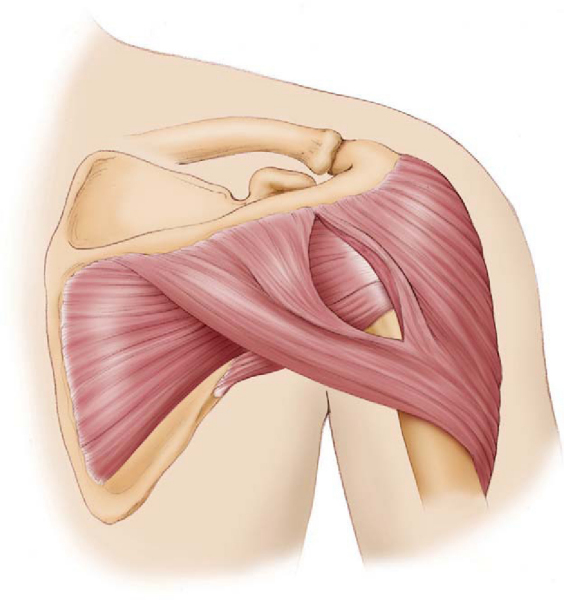

). The incision extends from the acromion to the axillary crease and may be shortened with increased experience with the approach. The posterior portal from diagnostic arthroscopy can be incorporated into the middle of the incision. Mentally and visually, the dissection is a direct extension of this portal. The orientation of the deltoid muscle fibers is defined and its fascia split in line with the fibers (

Fig. 12-2

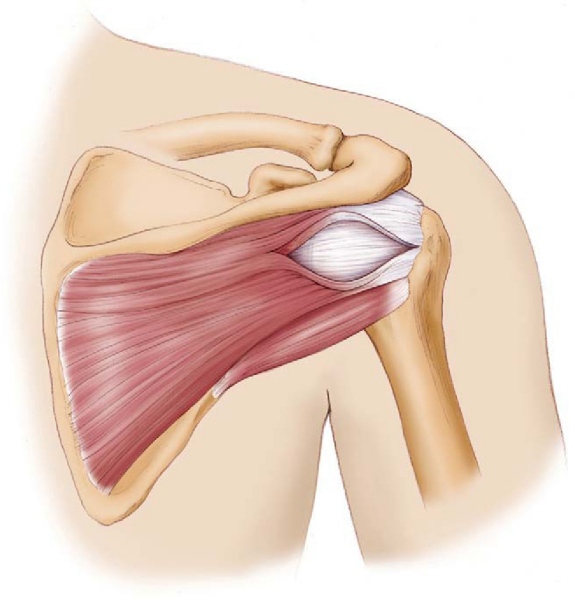

). The location of the deltoid split is directly over the glenohumeral joint determined by palpation of the joint between the surgeon’s thumb posteriorly and long finger anteriorly. Development of the interval in the deltoid exposes the fascia over the infraspinatus and teres minor. The center of the joint is again reassessed by manual palpation. A yellow fat stripe in the infraspinatus muscle is a frequently visible and reliable plane to explore. The overlying fascia is opened horizontally, and a dissection plane is made through infraspinatus muscle (

Fig. 12-3

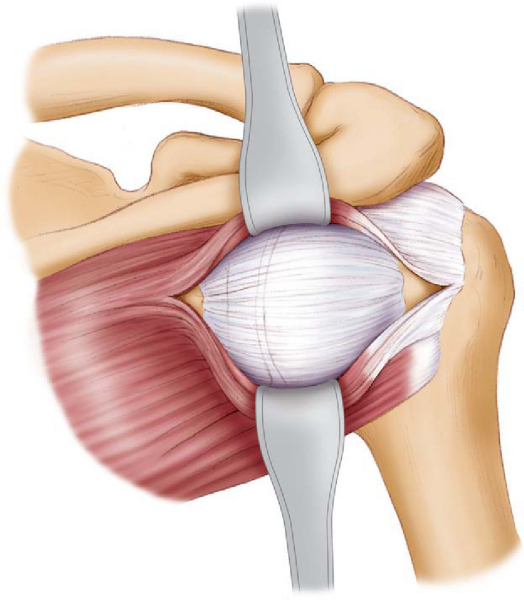

). Alternatively, dissection can proceed through the infraspinatus–teres minor interval, but more caution is necessary not to dissect inferior to the teres minor because of the proximity of the axillary nerve. At this point, it is critical to expose the entire posterior capsule, particularly inferiorly and laterally, where the infraspinatus is most adherent to the capsule. Patient, blunt dissection, deep right-angled retractors, and good assistants are helpful at this stage (

Fig. 12-4

). Dissection should be limited to 1 cm medial of the glenoid to avoid injury to the suprascapular nerve.

|

|

|

|

Figure 12-3 |

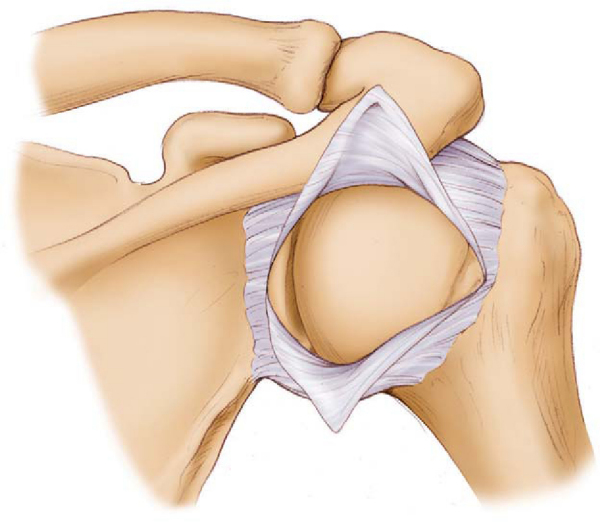

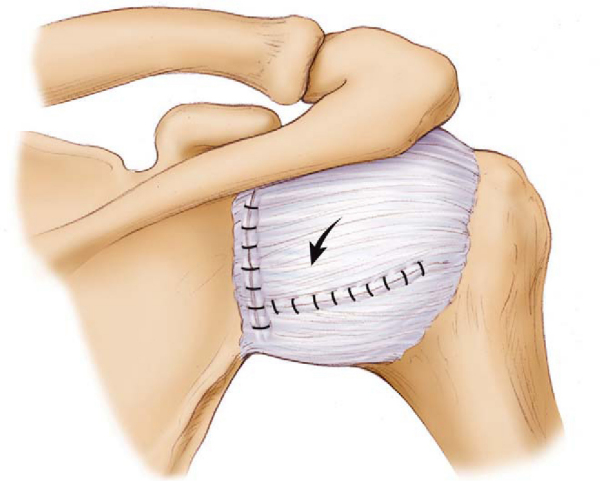

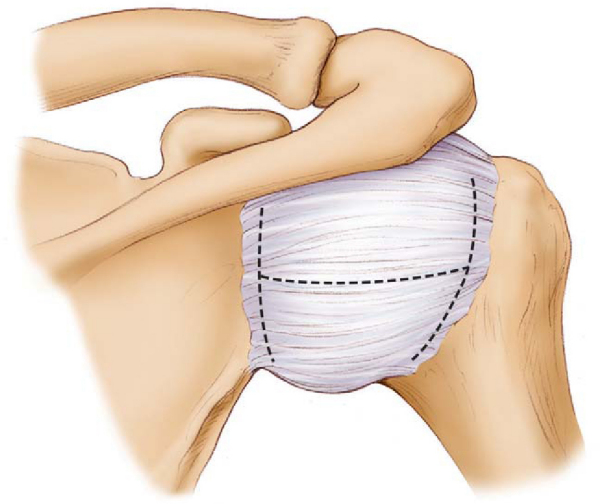

Once the capsule is completely defined, a horizontal incision centered over the middle of the joint is made from the glenoid extending laterally. A vertical incision is made just lateral to the capsular attachment to the glenoid to make a T-shaped pattern and two mobile flaps of capsule (

Fig. 12-5

). Complete mobilization of the inferior and superior flaps permits successful capsulorrhaphy (

Fig. 12-6

).

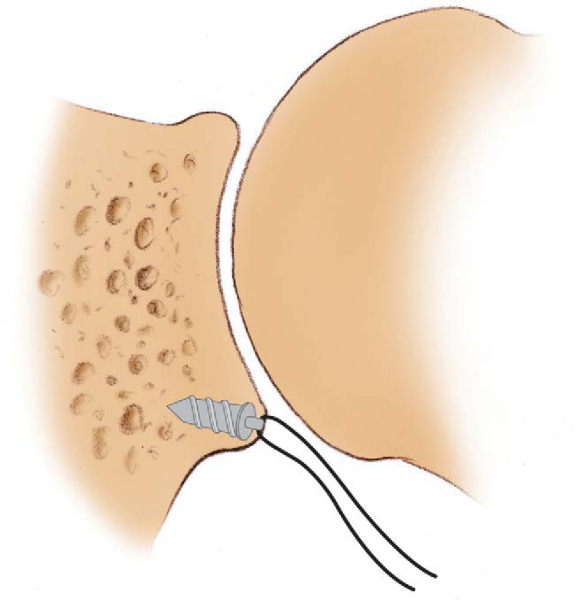

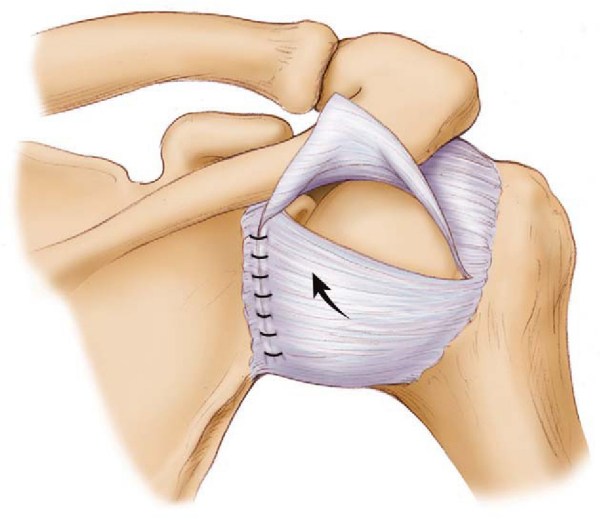

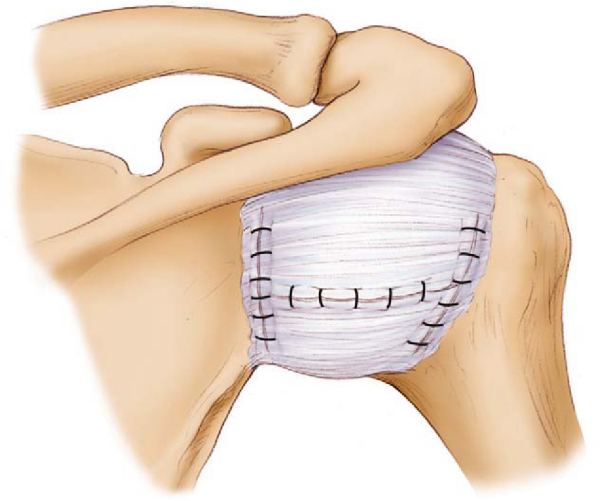

A humeral head retractor is used to investigate the posterior aspect of the glenohumeral joint. The condition of the posterior labrum can be difficult to visualize directly and is more accurately confirmed by prior arthroscopy. If the labrum is detached, suture anchors are placed under the labrum, on the posterior glenoid articular margin after débridement and roughening with a rasp or bur (

Fig. 12-7

). The sutures are placed through the labrum for repair in situ, and these sutures are tied and then used for the medial repair in the capsulorrhaphy. If the labrum is intact, nonabsorbable sutures can be placed through the labrum for repair of the capsule. The medial-based capsular shift is performed with the arm in 20 degrees of abduction and neutral rotation. The inferior flap is first advanced superiorly (

Fig. 12-8

), and then the superior flap is shifted inferiorly, overlapping the inferior flap (

Fig. 12-9

). Excessive capsular redundancy is eliminated by imbricating the horizontal capsulotomy during closure or by making a second vertical incision laterally for an H-type repair (Figs. 12-10 and 12-11 [10] [11]).

In the case of severe capsule deficiency, revision surgery, glenoid hypoplasia, or excessive glenoid retroversion, it may be necessary to augment the repair. Soft tissue augmentation is accomplished by vertically incising the infraspinatus at the level of the glenoid and securing it to the capsule and glenoid with use of the previously placed capsule repair sutures. Rarely, an extracapsular posterior bone block can be added for cases of glenoid deficiency or at revision when repaired capsule tissue is deficient. A tricortical graft 4 × 2.5 cm may be harvested from the scapular spine. The graft and glenoid neck are predrilled before capsular repair to ensure accurate placement. It is placed on the posteroinferior quadrant to increase glenoid depth without impinging on the humeral head. In addition, there are several reports of opening wedge glenoid osteotomy for excessive glenoid retroversion. This is usually reserved for patients with severe instability and glenoid retroversion of more than 10 degrees as determined by computed tomographic scan.

Typically, sutures are not necessary in the infraspinatus split or deltoid fascia. The skin incision is closed in a standard fashion.

| • | The arm is immediately placed in immobilization in an orthosis that maintains slight abduction, neutral rotation, and neutral flexion-extension. This is maintained for 4 weeks. | |

| • | The arm is maintained at neutral rotation for time out of the brace. Passive abduction in neutral rotation, in the plane of the scapula, is allowed. | |

| • | Sling protection is continued for weeks 5 and 6. |

| • | After week 6, begin active and passive range of motion without stretching internal rotation. | |

| • | Goal for range of motion: 90% by 12 weeks. | |

| • | Progressive resistance and strengthening exercises for the scapula and rotator cuff are begun and progressed as tolerated. | |

| • | Sport-specific and functional exercises are added when sufficient strength is restored. |

| • | Recurrent instability | |

| • | Injury to axillary nerve or posterior humeral circumflex vessels | |

| • | Injury to suprascapular nerve and vessels | |

| • | Overtightening of glenohumeral joint resulting in decreased range of motion and arthrofibrosis | |

| • | Infection | |

| • | Intraarticular fracture, nonunion, degenerative arthritis, and osteonecrosis of the glenoid are risks unique to glenoid osteotomy. |

Good to excellent results can be achieved in 75% to 90% of patients after most open procedures for isolated posterior instability. Results demonstrate minimal, acceptable decrease in range of motion, dramatic decrease in pain and instability, low rates of recurrence of instability, and ability to return to sport in many cases (

Table 12-1

).

| Author | Followup | Procedure | Outcome | Recurrent Instability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shin et al[8] (2005) | 3.9-year mean | Posterior capsular shift 8/17 posterior labral repair through bone tunnels |

13/17 (76%) good–excellent | 2/17 (11%) |

| Misamore and Facibene[6] (2000) | 45-month mean | Posterior capsular shift 1/14 posterior labral repair with anchor |

13/14 (92%) excellent | 1/14 (8%) |

| Fuchs et al[4] (2000) | 7.6-year mean | Posterior capsular shift 7/26 posterior labral repair with anchor 3/26 glenoid osteotomy 1/26 posterior bone block |

24/26 (92%) good–excellent | 6/26 (23%) |

| Bottoni et al[2] (2005) | 40-month mean | Posterior capsular shift | 11/12 (91%) good–excellent | 0 |

| Rhee et al[7] (2005) | 30-month mean | Posterior capsular shift | 25/30 (83%) good–excellent | 4/30 (13%) |

| Bigliani et al[1] (1995) | 5-year mean | Posterior capsular shift | 12/13 (92) good–excellent | NA |

| Tibone and Ting[9] (1990) | 5-year mean | Staple capsulorrhaphy | 11/20 (55%) acceptable | 6/20 (30%) |

| Hawkins and Janda[5] (1996) | 44-month mean | Posterior capsular shift 1/14 posterior labral repair with suture anchor |

13/14 (93%) satisfactory | 1/14 (7%) |

| Bowen et al[3] (1991) | 5-year mean | Posterior capsular shift 7/26 with bone block |

92% good–excellent | 3/26 (12%) |

| Wolf et al[10] (2005) | 7.6-year mean | Variety of posterior capsular plication procedures | 32/44 (72%) good–excellent, including 11 patients with multidirectional instability | 4/32 (13%) |

1.

Bigliani LU, Pollock RG, McIlveen SJ, et al: Shift of the posteroinferior aspect of the capsule for recurrent posterior glenohumeral instability.

J Bone Surg Am 1995; 77:1101-1120.

2.

Bottoni CR, Franks BR, Moore JH, et al: Operative stabilization of posterior shoulder instability.

Am J Sports Med 2005; 33:996-1003.

3.

Bowen MK, Warren FR, O’Brien SJ, Altchek DW: Posterior subluxation of the glenohumeral joint treated by posterior stabilization.

Orthop Trans 1991; 15:764-765.

4.

Fuchs B, Jost B, Gerber C: Posterior-inferior capsular shift for the treatment of recurrent, voluntary posterior subluxation of the shoulder.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000; 82:16-25.

5.

Hawkins RJ, Janda DH: Posterior instability of the glenohumeral joint: a technique of repair.

Am J Sports Med 1996; 24:275-278.

6.

Misamore GW, Facibene WA: Posterior capsulorrhaphy for the treatment of traumatic recurrent posterior subluxations of the shoulder in athletes.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2000; 9:403-408.

7.

Rhee YG, Lee DH, Lim CT: Posterior capsulolabral reconstruction in posterior shoulder instability.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005; 9:355-360.

8.

Shin RD, Daniel PB, Andrew RS, Zuckerman JD: Posterior capsulorrhaphy for treatment of recurrent posterior glenohumeral instability.

Bull Hosp Joint Dis 2005; 63:9-12.

9.

Tibone J, Ting A: Capsulorrhaphy with a staple for recurrent posterior subluxation of the shoulder.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990; 72:999-1002.

10.

Wolf BR, Strickland S, Riley WJ, et al: Open posterior stabilization for recurrent posterior glenohumeral instability.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005; 14:157-164.

Blasier et al., 1997.

Blasier RB, Soslowsky LJ, Malicky DM, Palmer ML: Posterior glenohumeral subluxation: active and passive stabilization in a biomechanical model.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997; 79:433-440.

Fronek et al., 1989.

Fronek J, Warren FR, Bowen M: Posterior subluxation of the glenohumeral joint.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1989; 71:205-216.

Hawkins et al., 1984.

Hawkins RJ, Koppert G, Johnston G: Recurrent posterior instability (subluxation) of the shoulder.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1984; 66:169-174.

Neer and Foster, 1980.

Neer II CS, Foster CR: Inferior capsular shift for involuntary inferior and multidirectional instability of the shoulder: a preliminary report.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1980; 62:897-908.

Norwood and Terry, 1984.

Norwood LA, Terry GC: Shoulder posterior subluxation.

Am J Sports Med 1984; 12:25-30.

Samilson, 1983.

Samilson RL: Posterior dislocation of the shoulder in athletes.

Clin Orthop 1983; 2:369-378.

Santini and Neviaser, 1995.

Santini A, Neviaser R: Long term results of posterior inferior capsular shift.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1995; 4(suppl):S65.