CHAPTER 32 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

Section – Arthroscopic Procedures

CHAPTER 32 – Arthroscopic Management of Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Elbow

Larry D. Field, MD,

Felix H. Savoie III, MD

Osteochondritis dissecans, a localized condition involving the articular surface, results in the separation of a segment of articular cartilage and subchondral bone. The most common site of osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow is the capitellum. Lesions have been reported in the trochlea and radial head as well as in the olecranon and olecranon fossa.[17]

Osteochondritis dissecans generally occurs in athletes aged 11 to 21 years who report a history of overuse. [4] [24] The osteonecrotic lesion involves only a segment of capitellum, primarily at a central or anterolateral position. [13] [27] Appropriate treatment of this disorder remains controversial. Often treated with benign neglect, this condition is a potentially sport-ending injury for an athlete, with long-term sequelae of degenerative arthritis. [1] [27] The surgical option that we present and have studied is fragment excision with débridement of the necrotic lesion.

Osteochondritis dissecans is primarily a disorder of the young athlete and rarely occurs in adults. The typical patient is between the ages of 11 and 21 years; the majority fall between 12 and 14 years. [4] [21] [24] Male athletes are more affected, but this disorder is prevalent among female gymnasts. The dominant arm is almost always involved, and bilateral involvement has been reported in some 5% to 20%.[25] A history of overuse is often described with common sport activities such as baseball, gymnastics, weightlifting, racket sports, and cheerleading.[22]

Pain, the most common complaint, is usually insidious and progressive in nature. Pain is often localized over the lateral aspect of the elbow, but it may also be poorly defined.[25] The pain is associated with activities and relieved by rest. Clinically, tenderness can be palpated laterally over the radiocapitellar joint.

Range of motion is limited, particularly extension. It is not uncommon to see flexion contractures of 5 to 23 degrees. [3] [4] [15] [23] [31] Loss of flexion is less likely; supination and pronation are rarely altered. Clicking, catching, grinding, or locking suggests fragment instability or loose bodies. Crepitus and swelling may be present as well. [4] [22] [24] [25] Provocative tests, such as the active radiocapitellar compression test, may help make the diagnosis.[2] As the patient actively pronates and supinates the forearm with the elbow in full extension, the dynamic muscle forces compress the radiocapitellar joint and reproduce the symptoms.

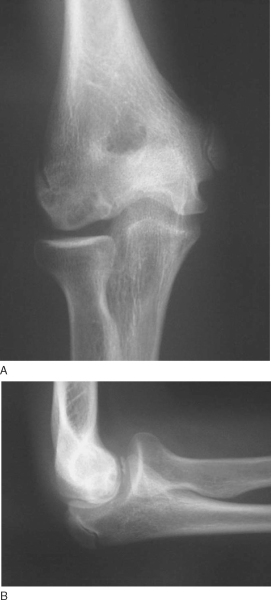

Radiographs are the initial diagnostic test of choice. Standard anteroposterior and lateral views of the elbow usually show the classic findings of radiolucency and rarefaction of the capitellum with flattening or irregularity of the articular surface. A rim of sclerotic bone often surrounds the radiolucent crater, which is typically in the central or anterolateral aspect of the capitellum (

Fig. 32-1

). Loose bodies may be present if the necrotic segment becomes detached.

|

|

|

|

Figure 32-1 |

Additional studies may be needed to further evaluate osteochondritis dissecans. Computed tomography is useful in determining the extent of the osseous lesion as well as the presence and location of loose bodies. Computed tomographic arthrography more accurately defines the integrity of the articular surface.[10]

Magnetic resonance imaging has become the standard modality for further evaluation. [4] [28] Not only can magnetic resonance imaging assess the articular surface, but it can also define both size and extent of the lesion (

Fig. 32-2

). Early, stable lesions show changes on T1-weighted images, but T2-weighted images remain normal. On the other hand, advanced lesions show changes on both T1- and T2-weighted images. [4] [8] Loose in situ lesions have a cyst under the lesion. Magnetic resonance arthrography can improve the diagnosis with leakage of dye beneath the disrupted cartilage. [8] [28]

|

|

|

|

Figure 32-2 . Increased signal of the T2 image indicates disruption of the articular surface. |

Progress and healing can be followed by plain radiographs. If the fragment remains stable, the central sclerotic fragment gradually becomes less distinct and the surrounding area of radiolucency slowly ossifies. A nonhealing lesion in a patient who remains symptomatic despite conservative treatment should prompt the clinician to evaluate further. [4] [27]

Indications and Contraindications

Treatment of osteochondritis dissecans is a highly debated topic. Options vary from nonoperative measures to fragment excision to fixation of the fragment. Management decisions are based primarily on the integrity of the articular cartilage and status of the involved segment, whether it is stable, unstable but attached, or detached and loose.

Stable lesions with intact cartilage and in situ subchondral fragments are managed conservatively. [4] [25] [28] Sports and other aggravating activities are stopped until symptoms subside, approximately for 3 to 6 weeks. We recommend protecting the elbow in a hinged elbow brace without restriction. The athlete can usually return to sports unrestricted 3 to 6 months after treatment is begun.[22] Patients with intact lesions detected early and treated conservatively have the best prognosis. However, it is prudent for the clinician to inform the family of possible long-term sequelae. [1] [11] [25] [26] [27] [28] [31]

Surgical indications are persistent or worsening symptoms despite prolonged conservative care, loose bodies, and evidence of instability including violation of intact cartilage or detachment. [4] [7] [18] [25] The only universally accepted regimen is the removal of loose bodies.[*] Otherwise, debate continues over two types of surgical manage ment. One method is to excise the unstable fragment with or without subchondral drilling or abrasion chondroplasty.[†] The other method is to attempt fixation of the segment with or without bone graft. [9] [12] [14] [19] [20] [29]

*

References 1-4, 7, 16-18, 23, 25, 26, 28, 30, 31 [1] [2] [3] [4] [7] [16] [17] [18] [23] [25] [26] [28] [30] [31].

†

References 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 11, 15, 16, 18, 22, 25-27, 30 [1] [3] [4] [6] [7] [11] [15] [16] [18] [22] [25] [26] [27] [30].

Specific Steps (

Box 32-1

)

We use general anesthesia and the prone position for arthroscopic evaluation of the elbow. The patient is placed prone on the operating table over chest rolls to ensure adequate ventilation. The shoulder is abducted to 90 degrees, and the arm is supported by an arm positioner or an arm board (

Fig. 32-3

). The arm board is placed parallel to the operating table, centered at the shoulder. A sandbag, foam support, or rolled blankets placed under the upper arm elevate the shoulder and allow the elbow to rest in 90 degrees of flexion.

| Surgical Steps | |||||||||||||||

|

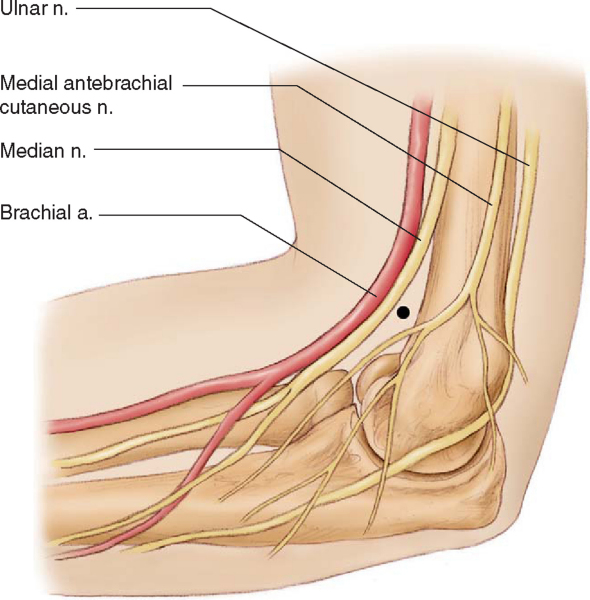

Surface landmarks are marked on the skin before portals are established. Important landmarks to outline are the radial head, olecranon, lateral epicondyle, medial epicondyle, and ulnar nerve (

Fig. 32-4

). Before the portals are made, the joint must be distended with 20 to 30 mL of sterile saline. This can be done by placing an 18-gauge spinal needle in either the olecranon fossa or the soft spot bounded by the lateral epicondyle, olecranon, and radial head. Neurovascular structures are displaced away from the joint with distention of the joint, which gives an additional margin of safety. [5] [15]

The arthroscope is introduced through the proximal anteromedial portal. This portal is 2 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle and just anterior to the medial intermuscular septum (

Fig. 32-5

). The medial intermuscular septum is identified by palpation, and the portal is made anterior to the septum so that the ulnar nerve is not injured. The blunt trocar is introduced into the portal, anterior to the septum, and aimed toward the radial head while contact is maintained with the anterior surface of the humerus. This allows the brachialis muscle to remain anterior and protect the median nerve and brachial artery. The trocar enters the elbow through the tendinous origin of the flexor-pronator group and medial capsule.[17]

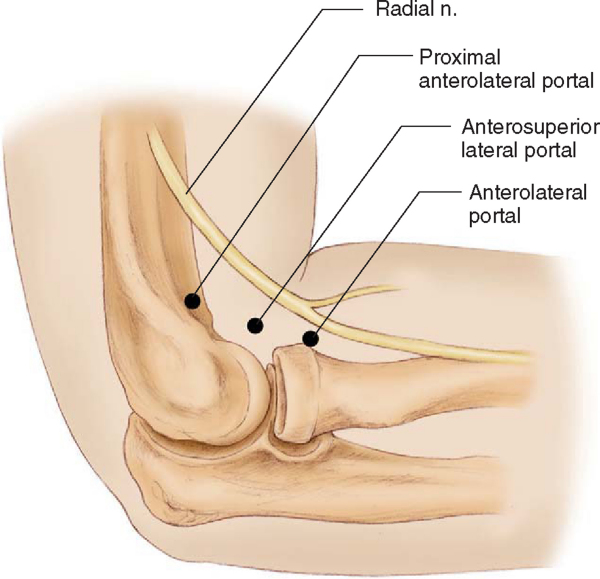

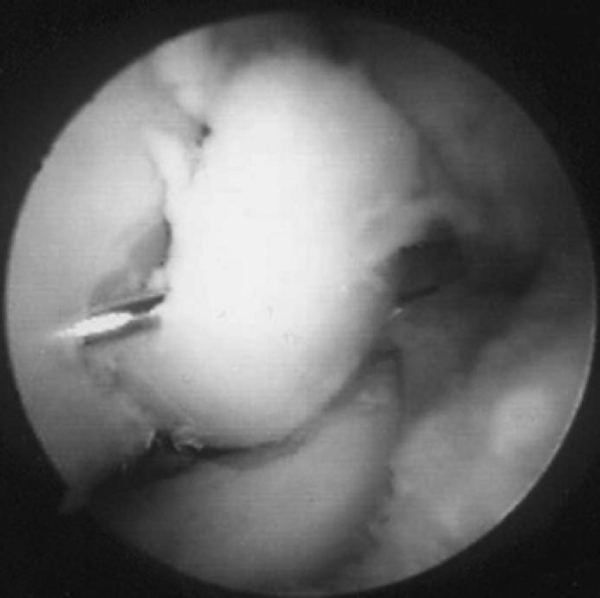

Once entrance into the joint is confirmed, the anterior aspect of the capitellum is evaluated. Loose bodies are removed through a proximal anterolateral portal. The proximal anterolateral portal is positioned 2 cm proximal and 1 to 2 cm anterior to the lateral epicondyle (

Fig. 32-6

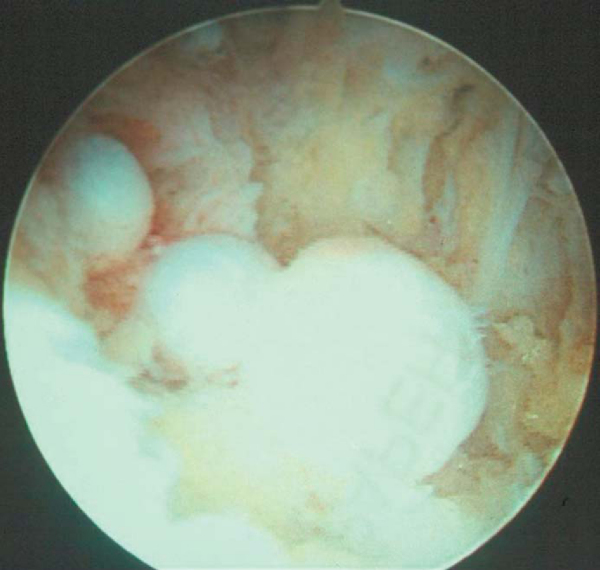

). This portal may be used as the initial portal in elbow arthroscopy. The blunt trocar is aimed toward the center of the joint while contact is maintained with the anterior humerus and pierces the brachioradialis muscle, brachialis muscle, and lateral joint capsule before entering the anterior compartment. The coronoid fossa is a common place for loose bodies to be localized (

Fig. 32-7

). Although the osteochondritic lesion may be noted on the anterior aspect of the capitellum (

Fig. 32-8

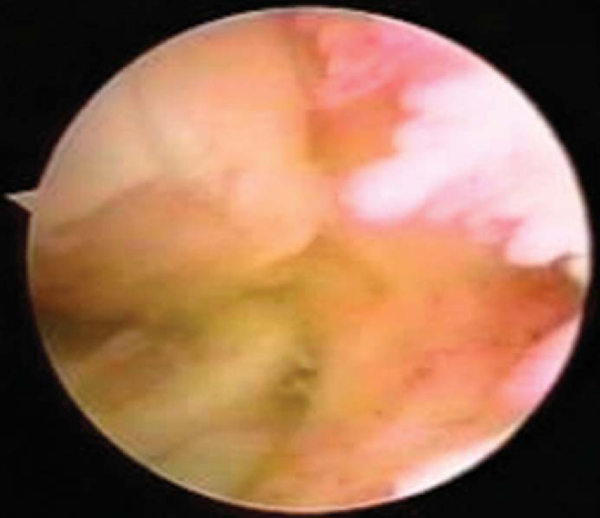

), it is most commonly noted on the posterior aspect and can be barely visualized with the scope in the anterior portal. One should always perform a varus and valgus stress test while the scope is in the anterior portal to document any concomitant instability of the elbow. Once a complete diagnostic arthroscopy of the anterior compartment of the elbow and removal of any associated loose bodies have been completed, the inflow is left in the proximal anteromedial portal and the scope is transferred to a straight posterior portal. The straight posterior or trans-triceps portal is located 3 cm proximal to the tip of the olecranon in the midline posteriorly [6] [16] (see

Fig. 32-4

). This portal allows visualization of the entire posterior compartment as well as the medial and lateral gutters.[17] The blunt trocar is advanced toward the olecranon fossa through the triceps tendon and posterior joint capsule. The medial gutter is evaluated initially along with the olecranon fossa, and any loose bodies noted in either of these are removed. The arthroscope is then continued into the lateral compartment, and a soft spot portal is established. In most cases of osteochondritis, a relatively large posterolateral plica will be noted, along with quite a bit of synovitis in this lateral compartment (

Fig. 32-9

). The soft spot portal is located in the center of the triangular area bordered by the olecranon, the lateral epicondyle, and the radial head. This portal is also known as the direct lateral portal or midlateral portal (see

Fig. 32-4

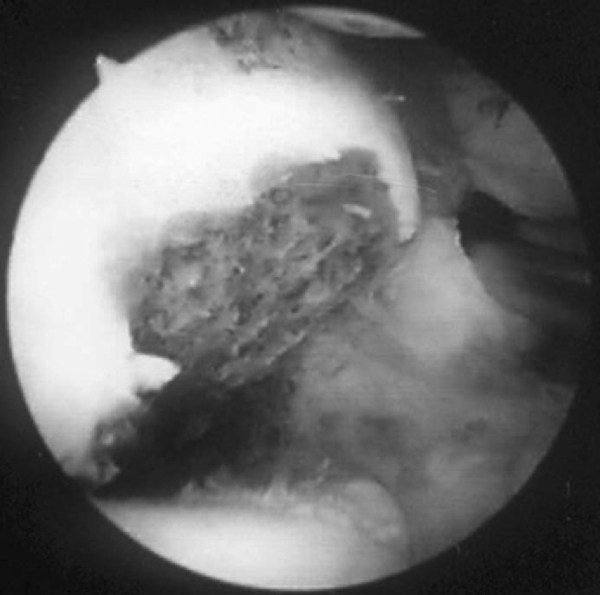

). The blunt trocar passes through the anconeus muscle and the posterior capsule and into the joint. This inflammatory tissue is excised through a posterior soft spot portal. At this point, the 30-degree arthroscope is removed and a 70-degree arthroscope is substituted through the posterior central portal. Use of the 70-degree arthroscope allows complete evaluation of the osteochondritic lesion of the capitellum (

Fig. 32-8

). The shaver is placed through the soft spot portal, and any loose fragments of the osteochondritic area are débrided. The necrotic bone is then removed, and in an attempt to stimulate blood flow, multiple drill holes are placed into the main body of the capitellum by use of either a drill or an awl (

Fig. 32-10

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 32-8 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 32-9 |

Fixation of the fragment remains controversial. Several techniques, including Herbert screw fixation,[9] dynamic stapling,[12] Kirschner wires,[11] cancellous screws,[4] and bioabsorbable implants, have been described. Before reattachment, the débrided bone can be grafted to encourage healing. Although several studies have shown favorable results after reattachment of the fragment, none has clearly demonstrated marked improvement over excision and débridement alone.

Rehabilitation after surgery starts with the patient in a double-hinged elbow brace, and early motion is begun. As the swelling and pain subside, patients are allowed to resume athletic activities in the brace. The brace is gradually weaned 8 to 12 weeks postoperatively, as long as the patient remains free of significant pain or any mechanical symptoms.

Few complications associated with the treatment of osteochondritis dissecans have been documented. One patient in our series developed severe arthritic changes in the radial head that required an additional surgery. To date, we have had no neurologic complications associated with the treatment of osteochondritis of the capitellum.

During the past 10 years, we have managed 23 elbows in 21 patients with osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum. Approximately 76% of these patients (16 of 21) have been treated nonoperatively by a double-hinged offloading elbow brace with selective anti-inflammatory medications and physical therapy. Of the 16 patients, 3 (19%) failed bracing and underwent subsequent arthroscopic débridement and drilling of displaced lesions. The remaining patients were also treated with surgery. The surgically treated group was observed for a mean of 44.3 months, and the average range of motion at latest examination was -3.5 degrees of extension to 135 degrees of flexion. One patient maintained his valgus instability and two patients continued to have mild pain. Radiographic evidence of lesion healing was present in 7 of the 10 elbows. Seven patients responded with a return to normal activities, but at a decreased level. One patient failed the procedure and had a radial head resection for severe arthrosis.

Results of surgical treatment of osteochondritis dissecans are shown in

Table 32-1

.

| Author | Type of Study | Patient Population | Type of Surgery | Followup Time | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baumgarten et al[3] (1998) | Retrospective | 16 adolescents 17 elbows |

Arthroscopic abrasion chondroplasty and/or loose body removal | Average: 48 months; minimum: 24 months | Average flexion contracture decreased by 14 degrees, extension contracture by 6 degrees All but 3 returned to preoperative level of activity |

| Byrd and Jones[6] (2002) | Retrospective | 10 baseball players Average age: 13.8 years |

Arthroscopic synovectomy, abrasion chondroplasty, and/or loose body removal | Average: 3.9 years | Excellent results in pain, swelling, mechanical symptoms, activity limitation, range of motion Grade of lesion correlated poorly with outcome |

| Ruch et al[23] (1998) | Retrospective | 12 adolescents Average age: 14.5 years |

Arthroscopic débridement and/or loose body removal | Average: 3.2 years | 11 patients reported excellent pain relief and no limitations of activities |

| Bauer et al[1] (1992) | Retrospective | 7 children younger than 16 years 23 adults older than 16 years |

23 loose body removal or removal of undisplaced lesion by open arthrotomy | Average: 23 years | Impaired motion and pain in half of elbows Degenerative joint disease in more than half |

1.

Bauer M, Jonsson K, Josefsson PO, et al: Osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow: a long-term follow up study.

Clin Orthop 1992; 284:156-160.

2.

Baumgarten TE: Osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum.

Sports Med Arthr Rev 1995; 3:219-223.

3.

Baumgarten T, Andrews J, Satterwhite Y: The arthroscopic classification and treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum.

Am J Sports Med 1998; 26:520-523.

4.

Bradley J, Petrie R: Osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum: diagnosis and treatment.

Clin Sports Med 2001; 20:565-590.

5.

Brown R, Blazina ME, Kerlan RK, et al: Osteochondritis of the capitellum.

J Sports Med 1974; 2:27-46.

6.

Byrd T, Jones K: Arthroscopic surgery for isolated capitellar osteochondritis dissecans in adolescent baseball players: minimum three-year followup.

Am J Sports Med 2002; 30:474-478.

7.

Chess D: Osteochondritis.

In: Savoie III FH, Field LD, ed. Arthroscopy of the Elbow,

New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996:77-86.

8.

Fritz RC, Stoller DW: The elbow.

In: Stoller DW, ed. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine,

2nd ed.. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:743-849.

9.

Harada M, Ogino T, Takahara M, et al: Fragment fixation with a bone graft and dynamic staples for osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002; 11:368-372.

10.

Holland P, Davies AM, Cassar-Pullicino VN: Computed tomographic arthrography in the assessment of osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow.

Clin Radiol 1994; 49:231-235.

11.

Jackson DW, Silvino N, Reiman P: Osteochondritis in the female gymnast’s elbow.

Arthroscopy 1989; 5:129-136.

12.

Kiyoshige Y, Takagi M, Yuasa K: Closed-wedge osteotomy for osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum: a 7- to 12-year followup.

Am J Sports Med 2000; 28:534-537.

13.

Konig F: Über freie Korper in den Gelenken.

Dtsch Zeitschr Chir 1887; 27:90-109.

14.

Kuwahata Y, Inoue G: Osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow managed by Herbert screw fixation.

Orthopedics 1998; 21:449-451.

15.

McManama Jr GB, Micheli LJ, Berry MV, et al: The surgical treatment of osteochondritis of the capitellum.

Am J Sports Med 1985; 13:11-21.

16.

Menche DS, Vangsness Jr CT, Pitman M, et al: The treatment of isolated articular cartilage lesions in the young individual.

Instr Course Lect 1998; 47:505-515.

17.

Mitsunaga MM, Adishian DA, Bianco Jr AJ: Osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum.

J Trauma 1982; 22:53-55.

18.

Nagura S: The so-called osteochondritis dissecans of Konig.

Clin Orthop 1960; 18:100-122.

19.

Nakagawa Y, Matsusue Y, Ikeda N, et al: Osteochondral grafting and arthroplasty for end-stage osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum: a case report and review of the literature.

Am J Sports Med 2001; 29:650-655.

20.

Oka Y, Ikeda M: Treatment of severe osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow using osteochondral grafts from a rib.

J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001; 83:838-839.

21.

Pappas AM: Osteochondritis dissecans.

Clin Orthop 1981; 158:59-69.

22.

Peterson RK, Savoie III FH, Field LD: Osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow.

Instr Course Lect 1998; 48:393-398.

23.

Ruch D, Cory J, Poehling G: The arthroscopic management of osteochondritis dissecans of the adolescent elbow.

Arthroscopy 1998; 14:797-803.

24.

Schenck Jr RC, Goodnight JM: Osteochondritis dissecans.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996; 78:439-456.

25.

Shaughnessy WJ: Osteochondritis dissecans.

In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and Its Disorders,

3rd ed.. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000:255-260.

26.

Singer KM, Roy SP: Osteochondrosis of the humeral capitellum.

Am J Sports Med 1984; 12:351-360.

27.

Takahara M, Ogino T, Sasaki I, et al: Long term outcome of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum.

Clin Orthop 1999; 363:108-115.

28.

Takahara M, Shundo M, Kondo M, et al: Early detection of osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum in young baseball players: report of three cases.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998; 80:892-897.

29.

Takeda H, Watarai K, Matsushita T, et al: A surgical treatment for unstable osteochondritis dissecans lesions of the humeral capitellum in adolescent baseball players.

Am J Sports Med 2002; 30:713-717.

30.

Tivnon MC, Anzel SH, Waugh TR: Surgical management of osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum.

Am J Sports Med 1976; 4:121-128.

31.

Woodward AH, Bianco Jr AJ: Osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow.

Clin Orthop 1975; 110:35-41.