Visual Field Examination

– Neurologic Examination > Cranial Nerve Examination > Chapter 13

– Visual Field Examination

the function of the visual pathway that begins in the eyes and ends in

the occipital cortex, because lesions located along different regions

of this pathway produce characteristic visual field abnormalities.

way of discovering significant visual field loss, and it should be

performed on all patients as part of a standard neurologic examination.

The nasal (medial) part of each retina sees the temporal visual world,

and the temporal (lateral) part of each retina sees the nasal visual

world. Visual information from each retina travels through the optic

nerves into the optic chiasm. At the optic chiasm, the visual

information from the nasal part of each retina crosses to the other

side and continues as the optic tract, whereas the visual information

from the lateral part of each retina remains uncrossed, also continuing

as the optic tract. Each optic tract synapses in the lateral geniculate

nucleus. From the lateral geniculate nuclei, the visual information

continues onward toward the occipital cortex as the optic radiations.

Visual information from the lower retina (which sees the upper fields)

travels through the optic radiations that are located in the temporal

lobes, reaching the lower occipital cortex. Visual information from the

upper retina (which sees the lower fields) travels through the optic

radiations that are located in the parietal lobes, reaching the upper

part of the occipital cortex.

-

Stand a few feet in front of the patient,

with your head at approximately the same level as the patient, looking

directly at the patient’s eyes. -

Instruct the patient to look at your nose

throughout the examination, and have the patient cover one eye with his

or her hand. Ask the patient to count the total number of fingers

you’ll be holding up. -

Check the visual fields by holding up

one, two, or five fingers in the vertical plane that is just between

you and the patient, checking each of the four quadrants. Test at least

four separate areas: the left and right upper visual fields and the

left and right lower visual fields. You do not need to hold the hands

far into the periphery, only approximately 1 ft away from the midline.

In most cases, you can quickly check both upper fields at the same time

(for example, by holding up one finger with your left hand and

P.44

two

fingers with your right hand, asking the patient to tell you the total

number of fingers you’re holding up), and then examine both lower

fields at the same time. If this is confusing to the patient, check

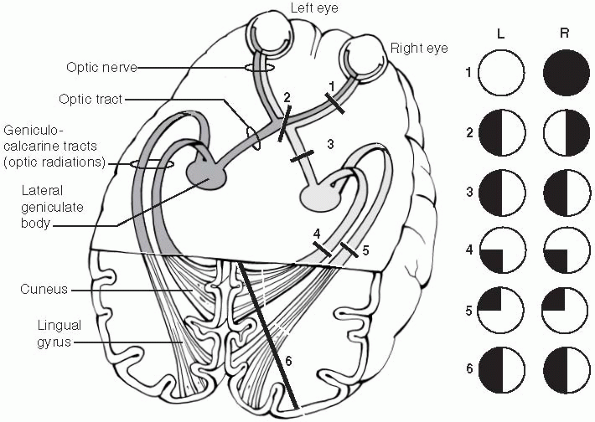

each quadrant separately. Figure 13-1

Figure 13-1

Illustration of the visual pathway from the eyes to the occipital

cortex. The characteristic visual field deficits that would occur due

to each of the numbered lesions at various regions of the visual

pathway are shown. See text for further details. (Redrawn from Gilman

S, Newman SW. Vision. In: Manter and Gatz’s essentials of clinical neuroanatomy and neurophysiology, 8th ed. Philadelphia: FA Davis Co, 1992:196.) -

Repeat the same process with the patient’s other eye closed.

all visual fields of each eye: the left upper quadrant, left lower

quadrant, right upper quadrant, and right lower quadrant.

-

An inability to count fingers in a visual field, or visual fields, is abnormal.

-

Visual field defects can occur from

dysfunction of the visual pathway anywhere from the eyes to the

occipital cortex. The typical visual field deficits that occur due to

lesions at different regions of the visual pathway are illustrated in Figure 13-1 and discussed below. -

Visual fields are characteristically

charted by drawing a circle representing the visual field of the left

eye and another circle representing the visual field of the right eye.

These are drawn as if you are the patient looking out: The left eye

field is drawn on the left and the right eye field is drawn on the

right. Intact visual fields are drawn as empty circles. Any abnormality

of a visual field is indicated by filling in that portion of the

P.45

circle.

Therefore, a patient with difficulty seeing in the left visual field of

both eyes would be drawn as shown for lesion 3 of Figure 13-1. -

Visual field deficits that involve one eye only are called monocular defects and occur due to dysfunction anterior to the optic chiasm, such as the optic nerve. Lesion 1 of Figure 13-1 shows a lesion of the right optic nerve causing right eye (i.e., monocular) blindness.

-

Bilateral temporal visual field defects

(bitemporal hemianopsias) occur from lesions at the optic chiasm, due

to dysfunction of the crossing fibers that arise from the nasal aspects

of each retina. Lesion 2 of Figure 13-1 shows a lesion at the optic chiasm causing a bitemporal hemianopsia. -

Visual field deficits that involve the same visual field of both eyes are called homonymous visual field defects

and are due to lesions posterior to the optic chiasm. Homonymous visual

field defects can involve one entire side of each eye (right or left

homonymous hemianopsias) or just the upper or lower quadrant (right or

left upper or lower quadrantanopsias). -

Homonymous visual field defects involving

an entire field (left or right homonymous hemianopsias) can arise due

to a lesion of the optic tract, both the upper and lower optic

radiations, or the occipital cortex. Lesion 3 of Figure 13-1 shows a left homonymous hemianopsia due to a lesion of the right optic tract. Lesion 6 of Figure 13-1 shows a left homonymous hemianopsia due to a lesion of the right occipital cortex. -

Homonymous quadrantanopsias occur due to

a lesion involving one of the (upper or lower) optic radiations or a

lesion involving just the upper or the lower part of the occipital

cortex. Lesion 4 of Figure 13-1 shows a left

lower quadrantanopsia due to a lesion of the right parietal optic

radiations, and lesion 5 shows a left upper quadrantanopsia due to a

lesion of the right temporal optic radiations.

-

Despite its simplicity and the rapidity

with which it can be performed, confrontational visual field testing is

a sensitive screening test that can detect significant visual field

abnormalities produced by brain or optic nerve lesions. -

It is optimal to perform confrontational

visual field testing of each eye individually, especially so that

monocular field defects can be detected. For an even more rapid

screening test of a patient who has no visual symptoms, however, it is

occasionally reasonable to cheat by performing confrontational visual

field testing with both of the patient’s eyes open, although this would

not exclude monocular defects. -

Patients with nondominant (usually right) hemisphere lesions may exhibit a phenomenon known as visual field extinction, also called extinction on double-simultaneous stimulation.

These patients may have normal visual fields when asked to count

fingers in the left or right fields separately, but they may ignore the

left-sided stimuli when fingers are held up in both fields

simultaneously. This finding is particularly suggestive of a right

parietal lesion and is discussed further in Chapter 31, Examination of Cortical Sensation.